Abstract

Temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) are the most frequent non-dental orofacial pain disorders and may be associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), resulting in oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD). However, clinicians’ understanding of involvement with OD caused by RA-related TMDs is limited and the methodological quality of research in this field has been criticised. Therefore, the aim of this study was to systematically review the prevalence of oral preparatory and oral stage signs and symptoms of OD in adults presenting with TMDs associated with RA. A systematic review of the literature was completed. The following electronic databases were searched from inception to February 2016, with no date/language restriction: EMBASE, PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, Elsevier Scopus, Science Direct, AMED, The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses A & I. Grey literature and reference lists of the included studies were also searched. Studies reporting the frequency of OD in adults presenting with TMD and RA were included. Study eligibility and quality were assessed by three independent reviewers. Methodological quality was assessed using the Down’s and Black tool. The search yielded 19 eligible studies. Typical difficulties experienced by RA patients included impaired swallowing (24.63%), impaired masticatory ability (30.69%), masticatory pain (35.58%), and masticatory fatigue (21.26%). No eligible studies reported figures relating to the prevalence of weight loss. Eligible studies were deemed on average to be of moderate quality. Study limitations included the small number of studies which met the inclusion criteria and the limited amount of studies utilising objective assessments. Valid and reliable prospective research is urgently required to address the assessment and treatment of swallowing difficulties in RA as TMJ involvement may produce signs and symptoms of OD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic autoimmune disorder of unknown aetiology affecting 1–3% of adults [1, 2]. It is characterised by progressive immune-mediated polyarticular inflammation of symmetrical synovial joint tissue, with frequent findings of joint effusion and synovial proliferation, progressing to joint destruction and/or ankylosis [3,4,5,6,7,8]. The average age of RA onset is between age 35 and 55 years, and this prevalence increases with age [1]. The female-to-male ratio is 2.5:1 [8]. Survival is 20% lower than healthy controls and increased mortality directly correlates with the severity of RA [9, 10]. The clinical course of RA is characterised by repeated remissions and exacerbations [6, 11]. Although RA typically affects small diarthrodial joints [11,12,13], peripheral manifestations of this pathology can include involvement of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) which occurs in up to 84% of RA patients [14,15,16,17]. Such involvement can potentially result in the development of concomitant temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) [11, 18, 19].

The most frequent orofacial pain disorders of non-dental origin are TMDs [20,21,22,23,24]. TMDs are a range of conditions commonly characterised by heterogeneous signs and symptoms and are reported to be the second most common musculoskeletal/neuromuscular disorders [20, 22, 25,26,27,28]. The prevalence of TMDs is controversial, with at least one sign or symptom estimated in up to 93% of the general population [29,30,31,32], with 10–20% of this cohort seeking treatment at some point [33,34,35,36]. TMDs are reported two to eight times more frequently in women than men. This is thought to be connected to oestrogen production, as exemplified by prevalence peaks in the second to fourth decades and decline during menopause [20, 30, 37,38,39,40]. TMDs are important to research, as symptoms have the potential to influence quality of life (QOL) [41, 42].

Typical findings in individuals presenting with TMDs associated with RA include joint sounds, myalgia of the associated musculature, and restricted mandibular movement [5, 10, 13, 43,44,45]. Bony TMJ destruction begins early in the RA disease process and can be objectively detected at 6 months post onset [43], with the most frequent radiographic findings at 5–10 years post onset including erosion, flattening, and resorption of the condyle [46,47,48,49]. Joint deformation can result in the development of signs and symptoms of oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD) [10, 13, 48, 50, 51]. For example, a range of oral preparatory and oral stage OD signs and symptoms relate to restricted ranges of mandibular motion, such as masticatory difficulties, masticatory pain and fatigue, increased oral transit times, and reduced cohesive bolus formation, with the potential for unintentional weight loss [52]. It is acknowledged that these signs and symptoms of OD can reduce oral health-related QOL and wellbeing within the RA population [53,54,55].

While research advocates the early management of RA-related TMDs via a myriad of methods which include ongoing objective and/or subjective assessments, pharmaceutical interventions, and diet modifications among other techniques [56], the medical profession’s acknowledgment of the presence and impact of RA-related oral manifestations would seem limited [10, 57], with physicians often prioritising the treatment of upper extremity and weight-bearing joints [13]. This may be in response to methodologically limited studies which under-emphasise the prevalence and impact of OD, perpetuating such practice patterns. In light of these clinical and research limitations, further research investigating the prevalence, nature, and potential impact of OD caused by RA-related TMDs is warranted.

The purpose of this study was to systematically review the epidemiology of oral stage signs and symptoms of OD within adults presenting with RA-related TMDs. Research aims were to examine the prevalence of the following oral stage OD signs and symptoms within the cohort of interest: impaired swallowing and masticatory ability, masticatory pain and fatigue, and unintentional weight loss.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review was executed in line with The PRISMA statement [58] and MOOSE guidelines [59]. The protocol was prospectively published on the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Prospero database (Registration number: CRD42016033528) [60]. For the purpose of this review, OD was defined as sensory and/or motor difficulties in the movement of a liquid or solid bolus from the oral cavity to the oesophagus, inclusive of concomitant emotional, cognitive, and functional difficulties [61].

Eligibility Criteria

All published/unpublished studies providing original prevalence figures were eligible for inclusion, with no language, geographic, or date limitations. Case reports were not included due to their low levels of evidence. Data regarding humans aged 18 years and over of any gender or race seen in any setting presenting with signs/symptoms of OD caused by RA of the TMJ were sought, with no disease duration, severity, or age-of-onset limitations. Individuals were excluded if they presented with a history of relevant comorbid conditions affecting the mandibular area (e.g., cancer of the head and/or neck, facial trauma, neurological injuries to the facial region). Individuals with histories of comorbid/congenital conditions affecting the mandibular or head and neck region were also excluded.

Outcomes of Interest

Outcomes investigated in this review included the following:

-

1.

impaired swallowing and mastication as reported subjectively and/or detected objectively through clinical examination, interviews, questionnaires, and/or imaging techniques;

-

2.

masticatory pain as reported via interviews, questionnaires, or as rated using subjective scales;

-

3.

masticatory fatigue as reported via interviews and questionnaires, or detected via clinical or electromyographic assessment; and

-

4.

unintentional weight loss as reported by the patient or detected via clinical examinations.

Data Sources

A sensitive search strategy using filters, MeSH, and key-text terms was systematically employed (“Appendix 1” section). Databases searched from inception to February 2016 were EMBASE, PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, Elsevier Scopus, Science Direct, AMED, The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses A & I. All records were exported to the Zotero bibliographic system (www.zotero.org). Following duplicate deletion, screening of titles/abstracts was independently conducted by three authors to exclude obviously irrelevant papers. Two of these authors screened one-third of potentially relevant records, two screened another third, and two others screened the final third. A fourth reviewer mediated disputes if they occurred. Hand-searches of the annual conference proceedings of the American College of Rheumatology (published in Arthritis and Rheumatology) and the International Association for Dental Research (published in the Journal of Dental Research), in conjunction with reference list searches of eligible studies, were conducted, with no eligible results identified. Following completion of the systematic searches discussed above, the authors also searched the Google Scholar database to further identify any papers not indexed in the directories initially searched, resulting in one additional eligible study [62]. Eligible articles included in the review were subsequently analysed.

Data Extraction Process and Data Items

Following piloting of an electronic data extraction form on a random sample of 20% of eligible studies, three authors extracted data regarding study design and location, demographics, outcome measurement, prevalence, and statistical analysis, among other parameters, reaching 100% agreement. One author not involved in data extraction mediated disputes. Two authors addressed missing data by contacting authors of studies published within the last 10 years. The period of 10 years was selected to allow for both the typical 5-year retention period observed in research and to also avoid forcible exclusion of studies if they were dated beyond this period, yet records were retained for post hoc analysis subsequent to expiration of the retention period. Exclusion of records occurred following no response to two contact attempts. Author contact was also carried out if prevalence figures were not directly reported in the primary study or if the authors were unable to calculate prevalence from the provided data.

Assessment of Methodological Quality

Methodological quality was independently examined by two authors using a modified version of the Down’s and Black tool [63] (Table 3 in “Appendix 2” section). This was modified to omit criteria regarding intervention, adverse events, blinding, and randomisation as these parameters were not relevant to this study’s aims. The authors reached 100% agreement regarding ratings. Primary studies which included a comparison group were marked out of a total of 18 points, while those without comparison groups were only scored out of a total of 16 points, as two criteria directly referred to the presence of a control group. Methodological quality was further independently rated by two authors using an adapted tool which was a combination of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [64] and Boyle critical appraisal checklists [65] (Table 4 in “Appendix 3” section). This adapted tool was used as a supplementary measure of methodological quality in order to pilot its use as an assessment of risk of bias tool.

Summary Measures and Synthesis of Results

The main characteristics of included studies were first described descriptively. Data from eligible studies were statistically analysed. Random-effects meta-analyses of prevalence estimates were conducted using the R statistical package (R core team, 2013, Austria). Prevalence was reported with 95% confidence intervals, with forest plots constructed for all prevalence estimates.

Results

Study Identification

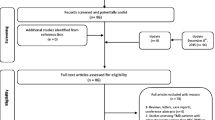

Systematic searches yielded 11,616 results, as shown in the PRISMA figure below (Fig. 1). Duplicate deletion resulted in the exclusion of 3561 records. The authors examined 132 full-texts and made 43 contact attempts to 30 researchers regarding 20 studies. For 2 of these studies, missing data were sought, while 18 communications were related to article access. Contact led to 6 eligible studies, the exclusion of 7 irrelevant studies, and 2 studies excluded due to insufficient data. Five studies were excluded due to inability to contact authors. Review authors identified no additional eligible articles from reference list or grey literature searches. Supplementary Google Scholar searches identified 1 further eligible study [62]. Therefore, 19 studies were ultimately included in the analysis.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Characteristics of included studies are described in Table 1.

The majority of included records (n = 13) were case–control studies (68.42%), 21.05% (n = 4) were descriptive observational studies, and 10.52% (n = 2) were cross-sectional studies. Study locations included South America (n = 3; 15.78%), Central America (n = 1; 5.26%), Europe (n = 11; 57.89%), Africa (n = 1; 5.26%), and the Middle East (n = 1; 5.26%). University hospital rheumatology clinics were the setting of the majority of studies (n = 10; 52.63%) (Table 1). Data pertaining to 1400 patients presenting with RA were extracted across 19 studies. The pooled age range of RA patients was 18–82 years, although 36.8% (n = 7) of studies did not provide details of age.

A majority of 84.21% of studies (n = 16) employed clinical stomatognathic evaluations and/or case histories and interviews (n = 7; 36.84%) as assessment tools. Questionnaires investigating symptoms, QOL, or participation were utilised in 52.63% (n = 10) of studies. Objective assessments, such as X-rays (n = 7; 36.84%), computed tomography (n = 3; 15.78%), laryngoscopy (n = 1; 5.26%), and MRI (n = 1; 5.26%), were utilised in several studies.

Assessment of Methodological Quality of Included Studies

Two authors independently reached consensus regarding quality ratings, without disagreements. Utilising the Down’s and Black tool, studies were awarded an average score of 11.5, indicating a typical standard of moderate quality (Table 2).

Ratings awarded utilising the modified Down’s and Black tool and amended JBI-Boyle checklist were highly correlated, with both tools providing overall average ratings of moderate quality.

The main items responsible for lower ratings of methodological quality were as follows: lack of estimates of random variability regarding main outcomes provided within 14 primary studies (73.68%); lack of description of the distribution of principal confounders in 7 studies (36.84%); and the lack of adequate accounting for confounding factors within statistical analysis in 7 studies (36.84%). Similarly, the lack of sufficient details provided in 11 primary studies (57.89%) to determine if samples were representative of the target population impacted negatively upon overall quality ratings. Contributing to positive quality ratings was the judgement that all studies (n = 19) described primary aims, hypotheses, and outcomes clearly, alongside all studies employing appropriate statistical tests within their analyses.

Prevalence of Investigated Outcomes

Based on estimates from three studies (n = 173 patients) [10, 66, 67], the prevalence of impaired deglutition was 24.63% (95% CI 14.21–39.2%) (Fig. 2).

An impaired ability to chew food was reported in nine studies (n = 863 patients) [10, 53, 54, 67,68,69,70,71,72]. The prevalence was calculated to be 30.69% (95% CI 19.24–45.14%) (Fig. 3).

Masticatory pain was reported in nine studies (n = 637 patients) [53, 61, 73,74,75,76,77,78,79], with the prevalence of this calculated to be 35.58% (95% CI 20.56–54.10%) (Fig. 4).

Masticatory fatigue was reported in three studies (n = 514 patients) [67, 79, 80]. This prevalence was calculated to be 21.26% (95% CI 4.10–63.01%) (Fig. 5).

Although specified as an outcome of interest, the prevalence of weight loss was not investigated in any included study.

Discussion

The findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis are noteworthy as they highlight the spectrum of OD signs and symptoms associated with RA-related TMDs, along with the limited research attention historically afforded to this condition. Impaired deglutition was present in 25% of RA patients, yet the included studies were characterised by methodological limitations restricting the validity and reliability of results. Therefore, the true prevalence may be higher than estimated in this study. Notably, 2 of the 3 included studies which addressed swallowing [10, 67] used only subjective questionnaires, while only 1 used objective imaging [66]. The frequent reliance on subjective assessments underlines the need for the increased use of combined subjective and objective assessments within TMD studies to ensure the validity and reliability of findings.

The disease processes involved in RA can cause occlusal changes and restricted TMJ movement, both of which can impair mastication [81]. Impaired mastication was estimated in approximately 31% of RA patients. However, methodological limitations render it difficult to determine true prevalence rates. For example, Larheim et al. [69]. described impaired chewing in 1 patient, yet no information is available regarding whether more patients were affected. Yilmaz et al. [70]. also reported chewing difficulties in 37.9% of RA patients, but it is unclear if difficulties were present in controls, and there were no responses to attempts to access supplementary data. As such, the provision of full datasets may be beneficial in future investigations of the epidemiology of masticatory difficulties.

This study estimated that a third of RA patients experienced masticatory pain (36%). This figure is higher than estimates from individuals experiencing TMDs of other etiologies. Chalmers and Blair [73] estimated that 10% of RA patients experienced masticatory pain, compared to 2.1% of mixed osteoarthritis/healthy controls, while Ogus [74] found masticatory pain in 19.23% of RA patients and 3.85% of controls. Similarly, Helenius et al. [78]. reported masticatory pain in 42% of RA patients, yet only 21% of controls. Masticatory pain may be related to RA inflammatory joint destruction, internal derangement, capsule stretching, synovitis, and muscle tenderness. As inflammatory joint changes are central to RA pathology, the epidemiology of this pain is crucial to investigate if patients are to be managed effectively.

Global and chronic fatigue originates from the pain, sleep difficulties, and emotional disturbances which often accompany RA [82]. The prevalence of specific masticatory fatigue was calculated to be 21%. Masticatory fatigue in individuals with RA is crucial to investigate further as it has been shown within wider OD clinical cohorts to result in lengthened mealtimes, reluctance to eat in public, and reduced QOL [83].

Finally, weight loss is a frequent consequence of OD in non-RA populations, potentially resulting in malnutrition, increased risk of infection and depression, and reduced wound healing [84]. Weight loss can also increase OD severity by reducing muscle and nerve function [84]. While anecdotal evidence of TMD-related weight loss exists, no studies addressing this outcome were identified. Therefore, investigation of this parameter is warranted. Also, the clinical involvement of dieticians and speech language pathologists in multidisciplinary management may be beneficial for individuals with RA.

Limitations

One key limitation is that few available studies met the review’s strict inclusion criteria. For example, case reports were excluded due to low levels of evidence and high propensity for bias [85]. This led to the exclusion of several records, which may have influenced estimates, despite methodological limitations. Also, only a limited number of eligible studies used objective assessments, with the subjective assessments used having varied psychometric properties. Finally, the conclusions presented are based on a small number of heterogeneous eligible studies. As such, reported frequencies are only estimates and true prevalence figures may be higher. Therefore, prospective epidemiological investigation of these parameters is warranted.

Recommendations

The use of inappropriate study designs in TMD research has been recently highlighted, with negative effects on methodological quality [10, 86]. The cross-sectional design is most appropriate for epidemiological investigations [87]. However, only two included studies used this design. Therefore, future TMD prevalence studies should adopt the cross-sectional design to increase methodological rigour. Recently, the American College of Rheumatology advised that low disease activity/remission with manageable pain levels and satisfactory levels of activity and/or QOL should be an RA treatment priority [88]. However, despite RA patients often experiencing OD, no evidence-based guidelines exist for its management. Therefore, remission/low disease activity levels may be unattainable, with residual TMJ complaints. Accordingly, rigorous research regarding OD caused by RA-related TMDs is required to ensure that patients are managed according to international best practice recommendations. Findings of this study should also motivate the development and validation of a psychometrically robust OD assessment for the RA and TMD populations, in order to inform management plans and improve the standard of care received by such patients.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis indicate that OD is consistently reported by a small cohort of adults presenting with RA of the TMJ, and that a small amount of methodologically limited research has been conducted on this phenomena. This study emphasises the need for further psychometrically sound epidemiological research regarding the presence, nature, and impact of OD in individuals with RA [89].

References

Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25.

Woo P, Mendelsohn J, Humphrey D. Rheumatoid nodules of the larynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113:147–50.

Kosztyła-Hojna B, Moskal D, Kuryliszyn-Moskal A. Parameters of the assessment of voice quality and clinical manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis. Adv Med Sci. 2015;60(2):321–8.

Akerman S, Kopp S, Nilner M, et al. Relationship between clinical and radiologic findings of the temporomandibular joint in rheumatoid arthritis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66(6):639–43.

Aliko A, Ciancaglini R, Alushi A, et al. Temporomandibular joint involvement in rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40:704–9.

McCarthy DJ. Pathology of rheumatoid arthritis and allied disorders. In: McCarthy DJ, editor. Arthritis and allied conditions. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1989. p. 647.

Roy N, Tanner K, Merrill RM, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of voice disorders in rheumatoid arthritis: prevalence, risk factors, and quality of life burden. J Voice. 2016;30(1):74–87.

Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Rheumatoid arthritis: epidemiology, pathology, and pathogenesis. In: Klippel JH, Stone JH, Crofford L, et al., editors. Primer on the rheumatic diseases. Atlanta, GA: Arthritis Foundation; 2001. p. 209.

Laurindo IMM, Pinheiro GRC, Ximenes AC, et al. Consenso brasileiro para o diagnóstico e tratamento da artrite reumatóide. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2002;42:355.

Bessa-Nogueira RV, Vasconcelos BC, Duarte AP, et al. Targeted assessment of the temporomandibular joint in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1804–11.

Sidebottom AJ, Salha R. Management of the temporomandibular joint in rheumatoid disorders. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51(3):191–8.

Voulgari PV, Papazisi D, Bai M, et al. Laryngeal involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25(5):321–5.

Lin YC, Hsu ML, Yang JS, et al. Temporomandibular joint disorders in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Chin Med Assoc. 2007;70(12):527–34.

Sodhi A, Naik S, Pai A, Anuradha A. Rheumatoid arthritis affecting temporomandibular joint. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015;6(1):124.

Delantoni A, Spyropoulou E, Chatzigiannis J, et al. Sole radiographic expression of rheumatoid arthritis in the temporomandibular joints: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 2006;102(4):37–40.

Seymour RL, Crouse VL, Irby WB. Temporomandibular ankylosis secondary to rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975;40(5):584–9.

Goupille P, Fouquet B, Cotty P, et al. The temporomandibular joint in rheumatoid arthritis. Correlations between clinical and computed tomography features. J Rheumatol. 1990;17(10):1285–91.

Helenius LMJ, Tervahartiala P, Helenius I, et al. Clinical, radiographic and MRI findings of the temporomandibular joint in patients with different rheumatic diseases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35(11):983–9.

Kohjitani A, Miyawaki T, Kasuya K, et al. Anesthetic management for advanced rheumatoid arthritis patients with acquired micrognathia undergoing temporomandibular joint replacement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60(5):559–66.

Manfredini D, Piccotti F, Ferronato G, et al. Age peaks of different RDC/TMD diagnoses in a patient population. J Dent. 2010;38(5):392–9.

Zakrzewska JM. Differential diagnosis of facial pain and guidelines for management. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):95–104.

Barghan S, Tetradis S, Mallya SM. Application of cone beam computed tomography for assessment of the temporomandibular joints. Aust Dent J. 2012;57(s1):109–18.

Nadendla LK, Meduri V, Paramkusam G, Pachava KR. Evaluation of salivary cortisol and anxiety levels in myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome. Korean J Pain. 2014;27(1):30–4.

Mello CE, Oliveira JL, Jesus AC, Maia ML, Santana JC, Andrade LS, Siqueira Quintans JD, Quintans Junior LJ, Conti PC, Bonjardim LR. Temporomandibular disorders in headache patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17(6):1042.

Di Fabio RP. Physical therapy for patients with TMD: a descriptive study of treatment, disability, and health status. J Orofac Pain. 1997;12(2):124–35.

Morales H, Cornelius R. Imaging approach to temporomandibular joint disorders. Clin Neuroradiol. 2015;1–18.

AlZarea BK. Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) in edentulous patients: a review and proposed classification (Dr. Bader’s Classification). J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(4):ZE06.

Greene CS, Klasser GD, Epstein JB. Revision of the American association of dental research’s science information statement about temporomandibular disorders. J Can Dent Assoc. 2010;76:115.

Poveda Roda R, Bagan JV, Diaz Fernandez JM, et al. Review of temporomandibular joint pathology. Part I: classification, epidemiology and risk factors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12(4):292–8.

Rutkiewicz T, Könönen M, Suominen-Taipale L, et al. Occurrence of clinical signs of temporomandibular disorders in adult Finns. J Orofac Pain. 2005;20(3):208–17.

Lamot U, Strojan P, Šurlan Popovič K. Magnetic resonance imaging of temporomandibular joint dysfunction-correlation with clinical symptoms, age, and gender. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;116(2):258–63.

Dworkin SF, Huggins KH, LeResche L, et al. Epidemiology of signs and symptoms in temporomandibular disorders: clinical signs in cases and controls. J Am Dent Assoc. 1990;120(3):273–81.

Pedroni CR, De Oliveira AS, Guaratini MI. Prevalence study of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in university students. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30(3):283–9.

Nassif NJ, Al-Salleeh F, Al-Admawi M. The prevalence and treatment needs of symptoms and signs of temporomandibular disorders among young adult males. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30(9):944–50.

Taylor M, Suvinen T, Reade P. The effect of grade IV distraction mobilisation on patients with temporomandibular pain-dysfunction disorder. Physiother Theory Pract. 1994;10(3):129–36.

Bertolucci LE, Grey T. Clinical analysis of mid-laser versus placebo treatment of arthralgic TMJ degenerative joints. Cranio. 1995;13(1):26–9.

Maixner W, Diatchenko L, Dubner R, et al. Orofacial pain prospective evaluation and risk assessment study–the OPPERA study. J Pain. 2011;12(11 Suppl):4–11.

Liu F, Steinkeler A. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of temporomandibular disorders. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57(3):465–79.

Isberg A, Hagglund M, Paesani D. The effect of age and gender on the onset of symptomatic temporomandibular joint disk displacement. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 1998;85(3):252–7.

Gesch D, Bernhardt O, Alte D, et al. Prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in an urban and rural German population: results of a population-based study of health in Pomerania. Quintessence Int. 2004;35(2):143–50.

Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, et al. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: recommendations of the international RDC/TMD consortium network and orofacial pain special interest group. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014;28(1):6–27.

Hazazi HSM. A retrospective analysis of in-patient temporomandibular disorders. 2015. http://search.proquest.com.elib.tcd.ie/pqdt/docview/1685875552/abstract/5CC51628BD6445E6PQ/12. Accessed Nov 2015.

Kahlenberg JM, Fox DA. Advances in the medical treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Hand Clin. 2011;27(1):11–20.

Chauhan D, Kaundal J, Karol S, Chauhan T. Prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in urban and rural children of northern hilly state, Himachal Pradesh, India: a cross sectional survey. Dent Hypotheses. 2013;4(1):21.

Navi F, Motamedi MHK, Talesh KT, Lasemi E, Nematollahi Z. Diagnosis and management of temporomandibular disorders. A textbook of advanced oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2013:831–58.

Gynther GW, Tronje G. Comparison of arthroscopy and radiography in patients with temporomandibular joint symptoms and generalized arthritis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1998;27:107.

Yoshida A, Higuchi Y, Kondo M, et al. Range of motion of the temporomandibular joint in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship to the severity of disease. Cranio. 1998;16:162.

Ueno T, Kagawa T, Kanou M, et al. Pathology of the temporomandibular joint of patients with rheumatoid arthritis–case reports of secondary amyloidosis and macrophage populations. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31(4):252–6.

dos Anjos Pontual ML, Freire JS, Barbosa JM, Frazão MA, dos Anjos Pontual A, da Silveira MF. Evaluation of bone changes in the temporomandibular joint using cone beam CT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2014:13.

Roy N, Stemple J, Merrill RM, et al. Dysphagia in the elderly: preliminary evidence of prevalence, risk factors, and socioemotional effects. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116(11):858–65.

Wise JL, Murray JA. Oral, pharyngeal and esophageal motility disorders in systemic diseases. 2006. GI motility online. http://www.nature.com/gimo/contents/pt1/full/gimo40.html. Accessed June 2016.

Chávez EM, Ship JA. Sensory and motor deficits in the elderly: impact on oral health. J Public Health Dent. 2000;60(4):297–303.

Ahola K, Saarinen A, Kuuliala A, et al. Impact of rheumatic diseases on oral health and quality of life. Oral Dis. 2015;21(3):342–8.

Hoyuela CPS, Furtado RNV, Chiari A, et al. Oro-facial evaluation of women with rheumatoid arthritis. J Oral Rehabil. 2015;42(5):370–7.

Elad S, Horowitz R, Zadik Y. Supportive and palliative care in dentistry and oral medicine. Xiangya Med. 2016;1(2).

Koh ET, Yap AU, Koh CK, et al. Temporomandibular disorders in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1918.

Abrão AL, Santana CM, Bezerra AC, de Amorim RF, da Silva MB, da Mota LM, Falcão DP. What rheumatologists should know about orofacial manifestations of autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia (English Edition). 2016;16.

Moher D, Liberat A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Gilheaney Ó, Harpur I, Sheaf G, et al. Protocol: the prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults presenting with temporomandibular disorders associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2016. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016033528. Accessed Feb 2016.

Tanner DC. Case studies in communicative sciences and disorders. Columbus: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2006.

El-Assy Kandil S, El-Rashidy A, et al. Otorhinolaryngological manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Med J Cairo Univ. 1994;62(3):647–57.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84.

Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, et al. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews: addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3:123.

Boyle MH. Guidelines for evaluating prevalence studies. Evid Based Ment Health. 1998;1(2):37–9.

Ekberg O, Redlund-Johnell I, Sjöblom KG. Pharyngeal function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis of the cervical spine and temporomandibular joint. Acta Radiol. 1987;28(1):35–9.

Kallenberg A, Wenneberg B, Carlsson GE, et al. Reported symptoms from the masticatory system and general well-being in rheumatoid arthritis. J Oral Rehabil. 1997;24:342–9.

Franks AS. Temporomandibular joint in adult rheumatoid arthritis. A comparative evaluation of 100 cases. Ann Rheum Dis. 1969;28(2):139–45.

Larheim TA, Storhaug K, Tveito L. Temporomandibular joint involvement and dental occlusion in a group of adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Odontol Scand. 1983;41(5):301–9.

Yilmaz HH, Yildirim D, Ugan Y, et al. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings of the temporomandibular joint and masticatory muscles in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(5):1171–8.

Aceves-Avila FJ, Chávez-López M, Chavira-González JR, et al. Temporomandibular joint dysfunction in various rheumatic diseases. Reumatismo. 2013;65(3):126–30.

Bono AE, Learreta JA, Rodriguez G, et al. Stomatognathic system involvement in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Cranio. 2014;32(1):31–7.

Chalmers IM, Blair GS. Rheumatoid arthritis of the temporomandibular joint. A clinical and radiological study using circular tomography. Quat J Med. 1973;42(166):369–86.

Ogus H. Rheumatoid arthritis of the temporomandibular joint. Br J Oral Surg. 1975;12(3):275–84.

Könönen M, Wenneberg B, Kallenberg A. Craniomandibular disorders in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis: a clinical study. Acta Odontol. 1992;50(5):281–8.

Goupille P, Fouquet B, Goga D, et al. The temporomandibular joint in rheumatoid arthritis: correlations between clinical and tomographic features. J Dent. 1993;21(3):141–6.

Voog U, Alstergren P, Leibur E, et al. Impact of temporomandibular joint pain on activities of daily living in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Odontol Scand. 2003;61:278.

Helenius LMJ, Hallikainen D, Helenius I, et al. Clinical and radiographic findings of the temporomandibular joint in patients with various rheumatic diseases. A case-control study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 2005;99(4):455–63.

Ahmed N, Mustafa HM, Catrina AI, et al. Impact of temporomandibular joint pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;597419.

Tegelberg A. Temporomandibular joint involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. A clinical study. Sweden: Odont.Dr. Lunds Universitet; 1987.

Marbach JJ, Spiera H. Rheumatoid arthritis of the temporomandibular joints. Ann Rheum Dis. 1967;26:538–43.

Tack B. Fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: conditions, strategies, and consequences. Arthritis Care Res. 1990;3:65–70.

Nund RL, Ward EC, Scarinci NA, et al. The lived experience of dysphagia following non-surgical treatment for head and neck cancer. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2014;16(3):282–9.

Wright L, Cotter D, Hickson M, et al. Comparison of energy and protein intakes of older people consuming a texture modified diet with a normal hospital diet. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2005;8(3):213–9.

Nissen T, Wynn R. The clinical case report: a review of its merits and limitations. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):264.

McNeely ML, Olivo SA, Magee DJ. A systematic review of the effectiveness of physical therapy interventions for temporomandibular disorders. Phys Ther. 2006;86(5):710–25.

Coggon D, Barker D, Rose G. Epidemiology for the uninitiated. New York: Wiley; 2009.

Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, et al. Update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(5):625–39.

Hobdell M, Petersen PE, Clarkson J, et al. Global goals for oral health 2020. Int Dent J. 2003;53(5):285–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Example of Database Search Strategy for PubMed

(“Arthritis, Rheumatoid”[Mesh] OR Rheumatoid[Title/Abstract] OR Rheumatism[Title/Abstract] OR Rheumatology[Title/Abstract] OR Arthritis[Title/Abstract] OR Arthritic[Title/Abstract]) AND (“Deglutition”[Mesh] OR “Deglutition Disorders”[Mesh] OR “Temporomandibular Joint”[Mesh] OR “Temporomandibular Joint Disorders”[Mesh] OR “Stomatognathic System Abnormalities”[Mesh] OR “Skull”[Mesh] OR “Jaw”[Mesh] OR “Mastication”[Mesh] OR Dysphagia[Title/Abstract] OR Dysphagic[Title/Abstract] OR Deglutition[Title/Abstract] OR Swallow[Title/Abstract] OR Swallows[Title/Abstract] OR Swallowing[Title/Abstract] OR Swallowed[Title/Abstract] OR “Mouth Opening”[Title/Abstract] OR Mandibular[Title/Abstract] OR Mandible[Title/Abstract] OR Temporomandibular[Title/Abstract] OR Stomatognathic[Title/Abstract] OR Masticatory[Title/Abstract] OR Mastication[Title/Abstract] OR Jaw[Title/Abstract] OR Jaws[Title/Abstract] OR Skull[Title/Abstract] OR Skulls[Title/Abstract] OR Cranium[Title/Abstract] OR Calvaria[Title/Abstract] OR Calvarium[Title/Abstract]).

Appendix 2

See Table 3.

Appendix 3

See Table 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gilheaney, Ó., Zgaga, L., Harpur, I. et al. The Prevalence of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Adults Presenting with Temporomandibular Disorders Associated with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Dysphagia 32, 587–600 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-017-9808-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-017-9808-0