Abstract

Purpose

Esophagojejunostomy is a challenging step in laparoscopic gastrectomy. Although the overlap method is a safe and feasible approach for esophagojejunostomy, it has several technical limitations. We developed novel modifications for the overlap method to overcome these disadvantages.

Methods

Forty-eight consecutive gastric cancer patients underwent totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy or laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with double-tract reconstruction at our institution from January 2019 to April 2020 using the overlap method with the following modifications. The esophagus was initially rotated by 90° counterclockwise, followed by transection of two-thirds of the esophageal diameter. The unstapled esophagus was then transected with a harmonic ultrasonic scalpel to enable esophagostomy at the posterior side of the esophagus. A side-to-side esophagojejunostomy was then formed at the posterior side of the esophagus using an endoscopic linear stapler through the right lower trocar. The common entry hole was closed via hand sewing method using V-Loc suture. This procedure was termed “esophagus two-step-cut overlap method.”

Results

Only one patient suffered from esophagojejunal anastomotic leakage but subsequently recovered after conservative treatment. Patients did not experience anastomotic bleeding or stricture.

Conclusion

Our modified overlap method provides satisfactory surgical outcomes and overcomes several technical limitations, such as entering the false lumen of the esophagus, unnecessary pollution caused by nasogastric tube, and unintended left crus stapling during anastomosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy was first described in 1994, and laparoscopic surgery has since been increasingly adopted for treating early and advanced gastric cancer [1, 2]. However, totally laparoscopic gastrectomy has been limited to some medical centers and a few expert surgeons. Intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy is a challenging step in totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy (TLTG) and laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with double-tract reconstruction (LPG-DTR). A range of approaches for intracorporeal esophagojejunal reconstruction utilizing linear or circular staplers has been described to overcome challenges and limitations of overlap method [3, 4]. Circular staplers have been used in esophagojejunostomy, but conducting purse-string suturing and anvil insertion under laparoscopic conditions is challenging. Surgeons commonly use linear staplers because of their ease of use. Esophagojejunostomy using linear staplers is increasingly performed due to technical advancements and increased surgical proficiency in this technique.

Linear staplers are commonly used in the overlap approach. Inaba et al. [5] first proposed the overlap method in 2010 and revealed that utilization of circular staplers is optimal for end-to-side anastomosis procedures because these linear staplers can easily be used in confined settings; moreover, the esophageal diameter remains unaffected whether or not stapling is performed. Compared with the functional end-to-end method, the overlap approach offers key advantages, such as alteration in jejunal directionality that can reduce anastomosis site tension [6]. Although many researchers have reported favorable outcomes associated with the overlap method [7,8,9], its limitations include difficulty in obtaining esophageal stump traction during anastomosis, increased risk of entering the false lumen of the esophagus, and susceptibility to unintentional left crus stapling during anastomosis. A modified technique for overcoming these limitations is presented in this study. Short-term outcomes of patients treated at our hospital via the proposed “esophagus two-step-cut overlap method” are presented in detail.

Material and methods

Patients

Forty-eight patients underwent TLTG or LPG-DTR using the modified overlap method for gastric cancer under the same surgeon (Yong-you Wu) at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University from January 2019 to April 2020. This study received approval from the institutional review board of the hospital, and patient medical records were evaluated to assess key clinicopathological parameters, such as sex, age, body mass index (BMI), tumor size, tumor location, and depth of invasion; TNM stage based on the eighth revision of the staging system of American Joint Committee on Cancer [10]; time the anastomosis was performed; time of oral intake; postoperative hospitalization duration; and mortality. Patients underwent upper gastrointestinal angiography before discharge.

Surgical techniques

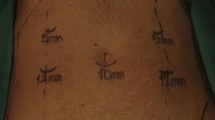

Patients were supine with legs spread and placed under general anesthesia. After pneumoperitoneum was established at the umbilicus, 2D laparoscope was inserted via this port with four (5 or 12 mm) operating ports placed in two sides of the upper abdomen (Fig. 1). Extended lymphadenectomy was conducted with stomach mobilization, and the soft tissue and vagus nerves around the esophagus were removed. The esophagus was held with a blocking clamp above the esophagogastric junction to avoid spillage of gastric juice (Fig. 2a). The exposed esophagus was rotated by 90° counterclockwise and transected by two-thirds of the esophageal diameter with a 60-mm Endo-Gia endoscopic linear stapler (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Norwalk, CO, USA), which enabled esophagostomy at the posterior side of the esophagus (Fig. 2b). Esophageal stump retraction was achieved by placing an intracorporeal suture (Ethicon Endosurgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) at the end of the stapled line (Fig. 2c). The unstapled esophagus was transected with a harmonic ultrasonic scalpel (UltraCision Harmonic Scalpel®; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, LLC, Guaynabo, Puerto Rico, USA) (Fig. 2d). The resected stomach was transferred into a plastic specimen bag, and this bag was retrieved via a small incision of 5 cm in the upper abdomen before reconstruction. The esophageal resection margin was determined to assess for cancer cells in the frozen biopsy. During the pathologic evaluation, jejunum was transected 25–30 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz with an endoscopic linear stapler. Jejunojejunal side-to-side anastomosis was formed approximately 50 cm beneath the esophagojejunostomy through the small incision. Gastrojejunostomy was subsequently performed in LPG approximately 15 cm below the end of the jejunum. A small enterotomy was performed on the antimesenteric side of the efferent jejunum 4–5 cm from the end of the jejunum. After temporarily closing the small incision using a protective sleeve, the pneumoperitoneum was re-established. Cartilage of a blue stapler was inserted through the enterostomy of the jejunum, and the anvil was inserted into the esophagostomy. An intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy was constructed with half the length of a 60-mm-long linear stapler to achieve an overlap of nearly 30 mm (Fig. 2e). The common entry hole was closed using hand sewing method with V-Loc suture (Medtronic/Covidien; Minneapolis, MN, USA) (Fig. 2f). Finally, we sutured mesenteric and Petersen defects to prevent internal herniation.

The modified overlap method in laparoscopic gastrectomy. (a) The axis of the esophagus was rotated 90° counterclockwise held with a blocking clamp above the esophagogastric junction. (b) Nearly two-thirds of the esophageal diameter is transected using an endoscopic linear stapler. (c) Place an intracorporeal suture at the end of the stapled line. (d) The unstapled esophagus was transected with a harmonic ultrasonic scalpel. (e) An intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy was constructed with half the length of a 60-mm-long linear stapler. (f) The common entry hole was closed using hand sewing method with V-Loc suture

Results

The present study included 14 female and 34 male patients with a median age of 67 years and a median BMI of 23.9. Approximately half of these patients had a tumor in the upper third of the stomach, with a mean tumor size of 4.0 cm. Cancer invaded the mucosa or submucosa in 8 (16.7%), proper muscle in 9 (18.6%), and subserosa in 27 (56.3%) patients. Among the 48 patients, 30 (62.5%) and 18 (37.5%) participants underwent TLTG and LPG-DTR, respectively. TNM stages II and III were the most common tumors among the patients (Table 1).

The majority of patients began drinking water 1 day postoperation and were permitted to consume a liquid diet gradually. Mean performing time of esophagojejunal anastomosis was 22.5 min, and conversion to open laparotomy was unnecessary for the patients. Patients were discharged 11.5 days postoperation on average (Table 2). With respect to anastomosis-associated complications, only one patient experienced esophagojejunal anastomotic leakage but subsequently recovered after conservative treatment. Patients did not suffer from postoperative anastomotic bleeding or stricture, wound-related issues, pancreatic fistulae, or luminal bleeding. Two patients experienced mechanical ileus postoperation, which was successfully managed with conservative treatment. Lung infection occurred in four patients but was resolved with antibiotic treatment. Adjuvant chemotherapy patients were treated postoperatively within 1 month, and patient mortality was absent during hospitalization.

Discussion

Similar to conventional open surgery, intracorporeal reconstruction of digestive tract, especially esophagojejunostomy, is difficult in laparoscopic surgery. Mechanical esophagojejunostomy in TLTG or LPG-DTR can be performed via circular and linear stapling. Characteristics of the circular stapler remarkably limit its application in total laparoscopic surgery. Linear staplers are commonly used by surgeons due to their ease of completion under laparoscopy. Linear staplers increase the chances of preventing anastomotic complications than circular staplers [11, 12].

The overlap method is a common linear stapler approach that was first introduced by Inaba et al. [5] in 2010; it offers sufficient intraluminal area and easy handling of staplers even in narrow spaces [13]. Clinicians have gradually introduced improvements to the overlap method due to its technical limitations. Petersen et al. [14] and Huang et al. [15, 16] have adopted the isoperistaltic jejunum-later-cut overlap method to simplify the procedure. The jejunum is first lifted and resected after the overlap anastomosis of the end of the esophagus. The procedure of dissociating the jejunum mesentery is omitted in the postdisconnection method. Kim et al. [17] applied two stitches with full-thickness suture at the esophagostomy site of the esophageal stump to guide the insertion of the stapler. The entry hole was then lifted with three sutures and closed with the endoscopic linear stapler. Yamamoto et al. [18] reported the superiority of operating the linear stapler with the surgeon’s right hand through the lower right port in the overlap anastomosis. A 3–0 absorbable suture that continuously closes the entry hole is turned clockwise by 90° while transecting the esophagus to improve the visual field for suturing the entry hole. Son et al. [19] demonstrated that the overlap method used at the left esophageal opening had a risk of unintended stapling of the left crus during the anastomosis; therefore, the researchers opened the center of the esophagus stump and sutured one stitch with a V-Loc suture on both sides of the opening. The entry hole was closed bidirectionally using presutured threads. This method was designated as the new modified overlap method that employs knotless barbed sutures (MOBS). Nagai et al. [20] modified the inverted T-shaped anastomosis in esophagojejunostomy using a linear stapler device by performing esophagojejunostomy in the jejunum vertical to the esophagus to improve the visual field during the manual suturing of the entry hole.

Anastomosis-related complication is the most important aspect of evaluating an anastomotic method. In 2014, Morimoto et al. [8] reported the surgical outcomes of 77 patients who underwent the overlap method, and the only anastomotic complication was a single case of stenosis. Similarly, in 2017, Son et al. [19] reported the outcomes of 40 consecutive cases using MOBS, and there were no anastomosis-related complications. In the present study, only one patient experienced esophagojejunal anastomotic leakage in our 48 cases, which had no significant increase compared with other studies. In addition, our approach has its own advantages and operability in many aspects. First, nearly two-thirds of the esophagus diameter was transected with an endoscopic linear stapler after rotating counterclockwise by 90°, and the unstapled esophagus was transected with a harmonic ultrasonic scalpel. Application of this technique can avoid unnecessary esophageal injury during secondary opening on the stapled line of the esophageal stump. At the same time, the opening of the esophagus was sufficiently large for easy identification of the lumen. Hence, avoiding the insertion of the endoscopic linear stapler into a “pseudolumen” that formed between the submucosal and muscular layers during esophagojejunostomy was crucial. The primary purpose of esophageal rotation was to improve the visual field for suturing the common entry hole. Moderate rotation helped the entry hole adopt the front position. A nasogastric tube was not utilized as a guide to the lumen in the esophageal stump to avoid unnecessary pollution and the risk of unintended stapling of the nasogastric tube during the anastomosis. Second, only half the length of the cartridge was used for the esophagojejunostomy. Excessive exposure of the lower esophagus was unnecessary. The esophagus typically has insufficient blood supply, and dissecting in the appropriate area above the mediastinum is crucial to devascularize the distal part of the esophagus. We closed the common esophagojejunostomy entry via suturing instead of using a linear stapler to avoid the problem of anastomotic stricture. Notably, stenosis was absent in the esophagojejunostomy anastomosis. Third, using our modified overlap method, esophagojejunostomy was performed on the esophageal posterior side to adjust to the ovoid hiatal opening shape easily. Accordingly, this overlap approach allowed easy food passage with a reduced risk of obstruction by the crus muscle. By using this approach, the common entry incision opened upward for sufficient intraoperative view and easy closure via hand suturing.

The overlap method is safe and practicable. The technical difficulties of the overlap method are the closure of the common entry, narrow space of esophagus and jejunum anastomosis, and the risk of anastomotic stenosis caused by mechanical anastomosis. At present, external knotting, application of V-Loc suture, and 3D laparoscopy reduce the difficulty of suturing under endoscopy and improve the feasibility of the operation. In the present study, we modified the overlap method to prevent complications and improve the ease of procedures. The proposed method can become a standard approach for intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy for patients with upper third gastric cancer.

Conclusion

Our modified overlap method provides satisfactory surgical outcomes and overcomes several technical limitations, such as entering the false lumen of the esophagus, unnecessary pollution caused by nasogastric tube, and unintended left crus stapling during anastomosis.

Data availability

It can be obtained through the corresponding author.

References

Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Shiromizu A, Bandoh T, Aramaki M, Kitano S (2000) Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy compared with conventional open gastrectomy. Arch Surg 135(7):806–810

Yu J, Huang C, Sun Y, Xiangqian S, Cao H, Hu J, Wang K, Suo J, Tao K, He X, Wei H, Ying M, Hu W, Xiaohui D, Hu Y, Liu H, Zheng C, Li P, Xie J, Liu F, Li Z, Zhao G, Yang K, Liu C, Li H, Chen P, Ji J, Li G, Chinese Laparoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study (CLASS) Group (2019) Effect of laparoscopic vs open distal Gastrectomy on 3-year disease-free survival in patients with locally advanced gastric Cancer: the CLASS-01 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 321(20):1983–1992

Kang SH, Cho Y-S, Min S-H, Park YS, Ahn S-H, Park DJ, Kim H-H (2019) Intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy using a circular or a linear stapler in totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy: a propensity-matched analysis. J Gastric Cancer 19(2):193–201

Kyogoku N, Ebihara Y, Shichinohe T, Nakamura F, Murakawa K, Morita T, Okushiba S, Hirano S (2019) Circular versus linear stapling in esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a propensity score-matched study. Langenbeck's Arch Surg 403(4):463–471

Inaba K, Satoh S, Ishida Y, Taniguchi K, Isogaki J, Kanaya S, Uyama I (2010) Overlap method: novel intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic total gastrectomy. J Am Coll Surg 211(6):e25–e29

Ko CS, Gong CS, Kim BS, Kim SO, Kim HS (2020) Overlap method versus functional method for esophagojejunal reconstruction using totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Surg Endosc 35:130–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07370-5

Kitagami H, Morimoto M, Nakamura K, Watanabe T, Kurashima Y, Nonoyama K, Watanabe K, Fujihata S, Yasuda A, Yamamoto M, Shimizu Y, Tanaka M (2016) Technique of Roux-en-Y reconstruction using overlap method after laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: 100 consecutively successful cases. Surg Endosc 30(9):4086–4091

Morimoto M, Kitagami H, Hayakawa T, Tanaka M, Matsuo Y, Takeyama H (2014) The overlap method is a safe and feasible for esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy. World J Surg Oncol 12:392

Lee T-G, Lee I-S, Yook J-H, Kim B-S (2017) Totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy using the overlap method; early outcomes of 50 consecutive cases. Surg Endosc 31(8):3186–3190

In H, Solsky I, Palis B, Langdon-Embry M, Ajani J, Sano T (2017) Validation of the 8th edition of the AJCC TNM staging system for gastric Cancer using the National Cancer Database. Ann Surg Oncol 24(12):3683–3691

Kawamura H, Ohno Y, Ichikawa N, Yoshida T, Homma S, Takahashi M, Taketomi A (2017) Anastomotic complications after laparoscopic total gastrectomy with esophagojejunostomy constructed by circular stapler (OrVil™) versus linear stapler (overlap method). Surg Endosc 31(12):5175–5182

Jeong O, Jung MR, Kang JH, Ryu SY (2020) Reduced anastomotic complications with intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy using endoscopic linear staplers (overlap method) in laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. Surg Endosc 34(5):2313–2320

Umemura A, Koeda K, Sasaki A, Fujiwara H, Kimura Y, Iwaya T, Akiyama Y, Wakabayashi G (2015) Totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: literature review and comparison of the procedure of esophagojejunostomy. Asian J Surg 38(2):102–112

Petersen TI, Pahle E, Sommer T, Zilling T (2013) Laparoscopic minimally invasive total gastrectomy with linear stapled oesophagojejunostomy--experience from the first thirty procedures. Anticancer Res 33(8):3269–3273

Huang C-M, Huang Z-N, Zheng C-H, Li P, Xie J-W, Wang J-B, Lin J-X, Lu J, Chen Q-Y, Cao L-L, Lin M, Tu R-H (2017) An isoperistaltic jejunum-later-cut overlap method for Esophagojejunostomy anastomosis after totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy: a safe and feasible technique. Ann Surg Oncol 24(4):1019–1020

Huang Z-N, Huang C-M, Zheng C-H, Li P, Xie J-W, Wang J-B, Lin J-X, Lu J, Chen Q-Y, Cao L-L, Lin M, Ru-Hong T, Lin J-L (2017) Digestive tract reconstruction using isoperistaltic jejunum-later-cut overlap method after totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: short-term outcomes and impact on quality of life. World J Gastroenterol 23(39):7129–7138

Kim HS, Kim BS, Lee S, Lee IS, Yook JH, Kim BS (2013) Reconstruction of esophagojejunostomies using endoscopic linear staplers in totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy: report of 139 cases in a large-volume center. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 23(6):e209–e216

Yamamoto M, Zaima M, Yamamoto H, Harada H, Kawamura J, Yamaguchi T (2014) A modified overlap method using a linear stapler for intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Hepatogastroenterology 61(130):543–548

Son S-Y, Cui L-H, Shin H-J, Byun C, Hur H, Han S-U, Cho YK (2017) Modified overlap method using knotless barbed sutures (MOBS) for intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy after totally laparoscopic gastrectomy. Surg Endosc 31(6):2697–2704

Nagai E, Ohuchida K, Nakata K, Miyasaka Y, Maeyama R, Toma H, Shimizu S, Tanaka M (2013) Feasibility and safety of intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic total gastrectomy: inverted T-shaped anastomosis using linear staplers. Surgery 153(5):732–738

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank colleagues at the department of gastrointestinal surgery in our hospital.

Funding

This study was funded by the gastrointestinal oncology international team cooperation project [NO. SZYJTD201804].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sun Ke-kang performed the research and wrote the paper; Wu Yong-you designed the research and supervised the report; Wang Zhen, Peng Wei, Cheng Ming, Huang Yi-kai, Yang Jia-bin, Zhu Bao-song, Gong Wei, Zhao Kui, and Chen Qiang provided clinical advice and supervised the report. Chen Zheng-rong, Ren Rui, Su Wen-zhao, and Liu Tian-hua supervised the report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data and photographs.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Kk., Wang, Z., Peng, W. et al. Esophagus two-step-cut overlap method in esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic gastrectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg 406, 497–502 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02079-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02079-y