Abstract

Background and purpose

Huntington disease (HD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder. There are no HD-specific measures to assess for end-of-life (EOL) preferences that have been validated for clinical use. The purpose of this study is to demonstrate reliability and validity of three HD-specific EOL measures for use in and clinical research settings.

Methods

We examined internal reliability, test–retest reliability, floor and ceiling effects, convergent and discriminant validity, known groups’ validity, measurement error, and change over time to systematically examine reliability and validity of the HDQLIFE EOL measures.

Results

Internal consistency and test–retest reliability were > 0.70. The measures were generally free of floor and ceiling effects and measurement error was minimal. Convergent and discriminant validity were consistent with well-known constructs in the field. Hypotheses for known groups validity were partially supported (there were generally group differences for the EOL planning measures, but not for meaning and purpose or concern with death and dying). Measurement error was acceptable and there were minimal changes over time across the EOL measures.

Conclusions

Results support the clinical utility of the HDQLIFE EOL measures in persons with HD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Huntington disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant progressive neurodegenerative disorder that impairs physical, cognitive, behavioral, and social function. The gene for HD (HTT) has been located on the short arm of chromosome four and predictive testing for the cytosine–adenosine–guanine (CAG) expansion mutation has been available since 1993 [1]. Typically, HD is diagnosed around age 40 with a clinical course of 15–20 years until death [2, 3]. Persons at risk for or diagnosed with HD typically have several years to make end-of-life plans. Knowing the unique features of the disease from watching and caring for family members, there may be end-of-life preferences specific to this population. Individuals at risk for or positive for the HD gene mutation have expressed end-of-life concerns that are important to quality of life [4]. As with any potentially life-threatening condition, persons with HD and their families experience a number of different emotions as they struggle with their feelings about mortality and end-of-life planning.

Until recently, no HD-specific tools existed to assist persons with HD, their families, and clinicians in identifying and addressing end-of-life preferences for persons with HD. This research team developed and validated the psychometric properties of new measures to assess end-of-life (EOL) issues in HD. These measures, HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose [5], HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying [5], and HDQLIFE End of Life Planning [6], were designed as part of a larger study to develop measures of HD quality of life (HDQLIFE) assessments to be used in clinical care and research [4]. These new measures provide a platform for collecting data about EOL concerns and preferences and may facilitate better understanding of these concerns and improve communication between families and providers [7]. Yet comprehensive data to support the clinical utility (i.e., reliability and validity) of these measures are not yet available. The 4-item HDQLIFE meaning and purpose [5] and the 16-item HDQLIFE concern with death and dying [5] are unidimensional; demonstrate good psychometrical properties; and are devoid of bias for age, gender and education. HDQLIFE EOL planning is a 16-item multidimensional scale that includes an overall total score and four subscale scores: legal planning, financial planning, preferences for care, and preferences for death and dying conditions at the time of death. Strong marginal reliabilities (i.e., IRT-based estimates of reliability) were found for total score and EOL planning subscales [6].

Given suggestions that advanced care planning may reduce patient and family stress, anxiety, and depression [8,9,10] more data are needed to support their use in the context of clinical care. Reliable and valid clinical measures could also be qualified as useful as outcomes for research involving HD-related quality of life. The goal of the present study was to determine the reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change over time of these new HDQLIFE EOL measures in persons with premanifest, early- and late-stage HD. Specifically, we examined data from study subjects with the HD mutation who completed baseline, 12-month, and 24-month assessments. We hypothesized these EOL measures would demonstrate sufficient reliability (i.e., internal consistency and test–retest reliability), would have minimal floor and ceiling effects, and would demonstrate appropriate convergent and discriminant validity. Given that no previous research has examined EOL preferences over the adult life span, we hypothesized these EOL measures would show known groups validity to differentiate between HD stages at each time point and show change over time.

Methods

Data for these analyses were drawn from the larger HDQLIFE study that developed and evaluated health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in persons with the autosomal dominant HD mutation across the HD spectrum, including premanifest, early-stage and late-stage HD (a detailed description of this study is provided elsewhere [11]). With respect to the current study, 507 participants completed several measures of HRQOL at baseline. Of these participants, 320 (63.1%) also completed the 12-month assessment, and 256 (50.4%) completed the 24-month assessment. Participants were recruited from eight HD clinics across the United States (Los Angeles, CA; Iowa City, IA; Indianapolis, IN; Baltimore, MD; Ann Arbor, MI; Golden Valley, MN; St. Louis, MO; Piscataway, NJ), and in conjunction with the PREDICT-HD study, a global cohort study with the purpose of assessing symptoms of HD in premanifest and early manifest individuals (n = 173 [34.1% participants were recruited in collaboration with the PREDICT-HD study [12]). In addition, several participants (n = 53) were recruited through HD-specialized nursing home units (Phoenix, AZ; Tucson, AZ; Minneapolis, MN; Cedar Brook, NJ; New York City, NY). Community outreach included assistance from the National Research Roster for Huntington’s disease, HD support groups, and articles/advertisements in HD-specific newsletters and websites. Study eligibility included either a positive gene test or a clinical diagnosis (made by a neurologist, physician, or other medical professional) of HD. Participants had to be ≥ 18 years of age, able to read and understand English, and be capable of providing informed consent (cognitive status was assessed using a standard assessment [13] in cases where there were concerns).

Institutional review board approval was obtained for all participating sites (University of Michigan Medical School Institutional Review Board, HUM00055669, approved 02/01/2012; Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board, IRB 13-460, approved 04/26,/2017; Indiana University Institutional Review Board [IRB-01], Protocol 1208009383, approved 09/07/2012; Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board, Study NA_00079341, approved 12/13/2012; University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, subsumed by Rutgers University, Institutional Review Board, Study ID Pro2012002196, approved 04/04/2013; Park Nicollet Institutional Review Board, Study 04334-13-A, approved 11/15/2013; University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board, IRB 13-10880 Reference 065701, approved 09/04/2013; University of California Los Angeles Institutional Review Board, IRB 12-000743, approved 06/12/2012; University of Iowa Institutional Review Board, IRB ID 201301724, approved 01/17/2013; and Washington University St. Louis Institutional Review Board, IRB ID 201206052, approved 08/14/2012). Written informed consent was provided by all participants prior to study enrollment. Each study visit (baseline, 12- and 24-months) lasted approximately 2 hours. Visits included an in-person assessment and completion of several self-report measures using an online data capture platform [14]. Study participants had the option of completing self-report measures online either at the time of the visit or at home (within 2 weeks of the initial study visit). Participants who were unable or unwilling to return to the clinic were given the option of completing the self-report measures via phone call.

Measures

Sample descriptive data

Demographic information including age, race, ethnicity, marital status, and education was collected using Assessment CenterSM. Medical records were obtained for each participant to confirm their gene status and to record CAG-repeat length. For premanifest participants, CAG-Age product (CAP) scores were calculated to provide an estimate of disease burden; CAP scores were used to classify premanifest participants as either low, medium, or high probability of conversion to manifest HD within the next 5 years [15].

HDQLIFE measures (HDQLIFE measures are available for download, free of charge, at https://www.hdqlife.com/ )

EOL HRQOL

Participants completed three different measures to assess self-reported EOL at baseline, 12- and 24-months: HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose [5], HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying [5], and HDQLIFE EOL Planning [16]. HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose is a 4-item short form that assesses the ability to make the most of the time left; HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying is an item bank that assesses thoughts about death and dying; and HDQLIFE EOL Planning is a 16-item multidimensional scale that assesses different components of end-of-life planning. The EOL Planning scale contains four subscales: (1) legal, which contains items related to advanced directives, health care power of attorney, and living wills, (2) financial care, which includes finances for long-term care, estate planning, life insurance, and support to make decisions, (3) preferences for care, which asks about palliative care, hospice, and nursing care, and (4) preferences for death and dying, which contains items related to preferences about death, conversations about death and dying, funeral arrangements, location of death preferences, and resuscitation preference. There is also an item pertaining to child care, which is not included in any of the subdomains, but does contribute to the total EOL Planning score.

The Meaning and Purpose short form is scored on a T metric (M = 50, SD = 10) relative to an HD population; higher scores indicate greater feelings of meaning and purpose. Concern with Death and Dying was administered as either a full item bank or as a computer adaptive test (CAT) plus short form depending on the study visit. At baseline n = 498 completed all of the items in the Concern with Death and Dying item bank; at 12-months n = 317 also completed all of the items in the bank; at 24-months 48% of the sample (n = 123) completed all of the items in the bank and the remaining 52% of the sample (n = 133) completed this measure as a CAT plus short form. Regardless of the format of administration, Concern with Death and Dying scores is on a T metric (M = 50, SD = 10) relative to a HD population; higher scores indicate greater preoccupation with thoughts of death and dying. Firestar software [17] was used to simulate CAT scores for persons completing all of the items in the bank. HDQLIFE EOL Planning is comprised of subscales (Legal Planning, Preferences for Care, Death and Dying Preferences, and Financial Planning) that can be combined into a total score. Subscale and total scores are on the same T metric, relative to an HD population.

Other health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) measures

Mental HRQOL

Several measures from the Neuro-QoL [18, 19] and PROMIS [20, 21] were included to provide assessments of positive and negative affect at baseline, 12- and 24-months. Neuro-QoL Positive Affect and Well-Being assessed positive mood and happiness. PROMIS Anxiety assessed fear, anxiety, and nervousness; and PROMIS Depression assessed sadness and depressed mood. These three measures are on a T-metric score (M = 50; SD = 10), where higher scores indicate more of the construct being measured (i.e., scores indicate better HRQOL). For the purposes of this study, we examined scores from the CAT administrations of these measures.

In addition, the RAND-12 [22] was administered to assess physical and mental health at baseline, 12, and 24, months. This 12-item questionnaire produces two component scores, the Physical Component Score (PCS) and Mental Component Score (MCS), each scored on the T-metric (M = 50; SD = 10); higher scores indicate better physical or mental health.

Clinician-rated measures

The Problem Behaviors Assessment-short form [23] (PBAs) provided a clinician-rated assessment of behavioral problems in HD at baseline, 12 and 24 months. Specifically, the PBAs [23] includes 11 items designed to assess depression, suicidal ideation, anxiety, irritability, aggression, apathy, perseverative thinking, obsessive compulsive behaviors, delusion, hallucinations, and disorientation. Each item includes a clinician rating of severity (range from 0 [symptom absent] to 4 [severe]) and frequency (range from 0 [never] to 4 [daily]). Scores for each item are calculated by multiplying the severity by the frequency score; higher scores indicate more behavioral problems. The PBAs also includes a total sum score of these 11 items. For this analysis, we examined item-level scores for suicide ideation and depression, as well as PBAs total scores.

The Unified Huntington Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS) [23] was administered at baseline, 12, and 24 months. For this study, the Total Motor Scale (TMS) and Total Functional Capacity (TFC) were used to rate severity of HD manifestations. After rating the total motor signs and the total functional capacity of each individual, the motor rater completed the Diagnostic Confidence Level (DCL), which provides a diagnosis of manifest HD. Specifically, the DCL item asks how much confidence is there that any abnormalities observed on the neurological TMS were unequivocal signs of HD from 0 (normal; no signs) to 4 (> 99% confidence that abnormalities in motor findings are secondary to HD). Participants with baseline ratings < 4 were included in the premanifest group, whereas those with ratings = 4 were included in the manifest HD groups. For the manifest group, TFC scores were used to determine HD disease stage. Specifically, the TFC provides an estimate of participant ability to maintain employment, complete finances without help, complete chores, complete ADL, and manage their own care as opposed to requiring a nursing home; scores range from 0 to 13 with higher scores reflecting higher functioning. For participants with manifest HD, those with baseline scores ranging from 7 to 13 were classified as early-stage HD, and those with scores less than 7 were classified as late-stage HD.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 [24]. Demographic information for the three HD groups (premanifest, early- and late-HD) was compared using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA; for continuous outcomes) and Chi-square analyses (for categorical data; Fisher’s exact test was used when cell counts were less than 5 [25]).

Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha (α; minimal acceptable level ≥ 0.70) [26] was used to determine internal consistency reliability of all HDQLIFE EOL short forms at each time-point; Cronbach’s α could not be calculated for the CAT version of Concern with Death and Dying, since the test is adaptive (participants do not answer the same items). In addition, a small subsample (n = 24) completed a retest of the EOL measures within 3 days to determine test–retest reliability using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) (minimal acceptable level specified as ≥ 0.70) [26].

Floor and ceiling effects

Floor and ceiling effects were defined as the percent of participants who received the best possible (floor) or worst possible (ceiling) score for each domain (minimal acceptable rates ≤ 20%) [27, 28]. We report floor and ceiling effects for the baseline, 12 and 24 month data.

Convergent and discriminant validity

Pearson correlations between the EOL measures and comparator measures were used to establish convergent and discriminant validity. We expect the highest correlations among similar constructs (convergent validity), and correlations of lower magnitude with less similar constructs (discriminant validity). Specifically, for HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying we expect the highest correlations with other self-reported mental health measures of distress (i.e., PROMIS Anxiety and Depression). For HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose we expected the highest correlation with Neuro-QoL Positive Affect and Well-being for HDQLIFE EOL Planning we expected higher EOL Planning to be associated with worse physical health. We consider correlation below 0.20 to be low and differences between correlation greater than 0.10 to be clinically relevant.

Known groups validity

At each time point, a one-way ANOVA was used to examine whether each HDQLIFE EOL measure could differentiate among the five different HD groups (premanifest low burden, premanifest medium burden, premanifest high burden, early-stage HD, and late-stage HD). For Concern with Death and Dying, we hypothesized that premanifest participants with low disease burden should report less concern than those who have medium burden, who should report less concern than those at high burden, who should report less concern than early-stage HD participants, who should report less concern than late-stage HD participants [29]. We did not expect group differences on Meaning and Purpose. For EOL Planning, we hypothesized those with late-stage HD would be more likely than the other groups to have made more plans and preparations for EOL.

Measurement error

Standard error of measurement (SEM), the estimate of the maximum difference between observed scores and true scores, was used to examine the measurement error for the EOL measures. For this analysis \({\text{SEM}} = {\text{SD}} \times \sqrt {1 - {\text{Cronbach}}'{\text{s}}\;{\text{alpha}}}\) [30,31,32]; baseline measurement errors (i.e., SDs) were used for all measures except the Concern with Death and Dying CAT where Cronbach’s alpha could not be calculated due to the adaptive nature of the measure (i.e., participants do not see the same items). For easier interpretability, SEMs are presented as percentages (SEM divided by the mean of all observations across time points, times one-hundred) [33]. SEM percentages less than 10% indicate good measurement error [33, 34].

Change over time

A linear mixed model (LMM) examined change over time for the EOL measures. Each model used restricted estimation of maximum likelihood (REML) with an unstructured covariance matrix and a random intercept term to allow for differences between participants using all available data. Models included time and disease stage as predictors of EOL measure scores. Separate models were examined for Concern with Death and Dying, Meaning and Purpose, and EOL Planning total score. We hypothesized increases in Concern with Death and Dying over time regardless of HD group. We did not expect changes in Meaning and Purpose over time. Finally, we expected more planning and preparation over time for all HD groups (with the largest increases in planning for the early-stage group).

Given that establishing and understanding the psychometric performance of a patient-reported outcome measure is an ongoing process [35, 36], we consider acceptable support for the EOL measures would be met if ≥ 75% of results concurred with the proposed hypotheses [37].

Results

We examined 507 study participants with premanifest (n = 198) and manifest (early-HD n = 200; late-HD n = 109) HD; see Table 1 for detailed descriptive data. The premanifest group was approximately 9 years younger than the early-HD group (M = 52.1; SD = 12.3) and 12 years younger than the late-HD group (M = 55.0; SD = 12.1; F[2,504] = 41.7; p < 0.0001). This was expected given the average age of onset and progressive nature of the disease. The sample was 59% female, and the groups did not differ on gender (χ22 = 3.44; p = 0.1794). The sample was primarily white (95.7%); however, there were significant differences between the groups as the late-HD group had a higher proportion of African American participants (7.3%) than the early-HD (2.0%) and premanifest (0.0%) groups (Fisher’s exact p = 0.0002). There were also differences in years of education, as the premanifest group (M = 16.0; SD = 2.8) had more years than the early-HD (M = 14.7; SD = 2.8) and late-HD (M = 14.2; SD = 2.5) groups (F[2, 487] = 18.92; p < 0.0001). Group differences were also present in marital status; the early-HD group (55.1%) had fewer participants who were married than the premanifest (66.7%) and late-HD (61.7%) groups (Fisher’s Exact p = 0.0059). Additionally, the late-HD group (M = 44.6; SD = 7.1) had a higher number of CAG repeats than the premanifest (M = 42.2; SD = 3.0) and early-HD (M = 43.0; SD = 3.7) groups. A large proportion of participants (46.2%) in the premanifest group was considered high burden, and thus were considered more likely to convert to manifest HD within the 5 years after baseline.

Of the 507 participants who completed the baseline assessments, 320 (63.1%) completed their 12-month visit and 256 (50.4%) completed the 24-month visit. Attrition at 24 months was found to be related to HD disease stage (χ22 = 14.09; p = 0.0009) as those who were late-stage at baseline were more likely to drop out of the study. Race was also a factor in study retention, as African Americans (Fisher’s exact p = 0.0333) were more likely to drop out of the study than other races. Other factors that predicted study retention were marital status (single and widowed were more likely to drop out; χ24 = 9.82; p = 0.0435) and having a lower CAG repeat length (odds ratio = 0.91; 95% CI 0.86–0.97; p = 0.0048).

Reliability

Internal consistency was supported for all scores on the EOL measures except the preferences for care subdomain score of EOL Planning domain (Table 2). All HDQLIFE EOL measures were generally free of floor and ceiling effects (Table 2). The pattern of findings was the same at all time-points. Test–retest reliability met criteria for > 0.70 for all HDQLIFE EOL measures (Table 2).

Convergent and discriminant validity

Given that the pattern of correlations was virtually identical for the baseline, 12-, and 24-month data, we present findings for baseline data only. Specifically, the pattern of correlations was consistent with the proposed hypotheses supporting convergent and discriminant validity for concern with death and dying, meaning and purpose, and EOL planning (see Tables 3, 4, and 5, respectively). The highest correlations for HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying were PROMIS measures of Depression (r = 0.59–0.60) and Anxiety (r = 0.56–0.57), the RAND-12 mental health (r = 0.45–0.47), and Neuro-QoL Positive Affect and Well-being (r = 0.40–0.44). The best positive association for HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose was with Neuro-QoL Positive Affect and Well-being (r = 0.63) and the highest negative correlations were with PROMIS Depression (r = 0.42) and Anxiety (r = 0.35) and the RAND-12 mental health (r = 0.37). The highest correlations for the EOL subdomain scores were with the EOL Planning total score (r = 0.68–0.79) and the other subdomains (r = 0.31–0.79). Other high correlations with the EOL Planning total score were HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying (r = 0.23–27). Highest correlations for EOL Legal were the RAND-12 mental and physical health (r = 0.15 for both measures). Highest correlations for EOL Financial were HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose (r = 0.17) and RAND-12 mental health (r = 0.16). Highest correlations for EOL Care Preferences were HDQLIFE Death and Dying short form (r = 0.21) and the RAND-12 physical health (r = 0.21). Highest correlations for Death and Dying Preferences were HDQLIFE Death and Dying CAT and short form (r = 0.18–0.23) and RAND-12 physical health (r = 0.17). The strongest associations for the PBAs suicide score were the HDQLIFE Concern with Death and Dying scores (r = 0.27–0.31), whereas correlations with HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose (r = 0.17), EOL Planning total (r = 0.16) and subdomain EOL Death and Dying Preferences (r = 0.15) were much lower.

Known groups’ validity

We did not identify group differences for concern with death and dying or for meaning and purpose (Table 6). For EOL planning, there were group differences for EOL Total scores (at all three time points), legal planning (at all three time points), financial planning (at 12- and 24-months), and preferences for care (at baseline and 12-months), but not for death and dying preferences (Table 6).

Measurement error

Measurement error was acceptable for all EOL scores (see Table 7).

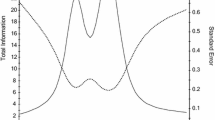

Change-over time

There were some unexpected findings with regard to change-over time on the HDQLIFE EOL measures (Table 8). In general, there were minimal changes over time in EOL measures. While we expected no change with regard to Meaning and Purpose, findings were contrary to our hypotheses for Concern with Death and Dying (where we expected increases over time), and for most of the EOL Planning scores (where we expected increases). There were no changes over time for any measure of Concern with Death and Dying or Meaning and Purpose. Hypotheses were supported for both manifest HD groups (early- and late-stage HD) for the EOL Planning—preferences for care score which significantly increased from baseline to 12 months (Fig. 1). Change from 12 to 24 months, however, showed a significant decrease for both of these groups, which was contrary to the proposed hypotheses. The change scores for this EOL Planning Preferences for Care measure did not differ from baseline to 24 months.

For all measures, well over 75% of supporting analyses were consistent with proposed hypotheses [37], supporting the clinical utility of these measures in persons with pre-symptomatic or manifest HD (Table 9).

Discussion

This analysis provides strong psychometric support for the reliability and validity of the HDQLIFE EOL measures in persons with HD First, a priori criteria were met for internal consistency reliability (with the exception of EOL-Planning Preferences for Care) and test–retest reliability. In addition, the majority of the EOL measures were devoid of floor and ceiling effects; exceptions were small floor effects for Meaning and Purpose and EOL-Planning—Legal Planning subdomain and a small ceiling effect for EOL-Planning—Preferences for Care subdomain. Measurement error was also within acceptable limits for all of the EOL measures.

There was also strong support for convergent and discriminant validity for the EOL measures; the only exception was that Meaning and Purpose had less robust correlations with clinician-rated suicidality and depression. While this finding was somewhat unexpected, it is consistent with literature suggesting that clinicians underestimate patient-reported positive affect [36].

Findings for known groups validity and change-over time were generally consistent with pre-study hypotheses. The results were consistent with hypotheses for Meaning and Purpose, EOL Planning Total score, and three of the four subdomain scores for EOL-Planning, but not for Concern with Death and Dying. Although some findings were inconsistent with our hypotheses, literature in other clinical populations indicates that declines in positive affect can be subtle (and may be mediated by perceptions of control [38,39,40,41]. Positive affect and well-being typically remains stable until ~ 5.6 years prior to death [40]. Thus, we may not expect differences between premanifest and early-HD participants. Sample size and drop outs may also have limited the power of this analysis in late-stage HD participants within 5 years of the end-of-life. Our data suggest that EOL planning may be relatively stable [42,43,44] precluding group differences on this measure.

We did not anticipate change-over time for Meaning and Purpose, but did expect increased EOL Planning and Concern with Death and Dying, which we did not find. Despite some exceptions to this (i.e., EOL Planning Preference for Care had increases from baseline to 12 month followed by decreases from 12 to 24 months) the change from baseline to 24 months was not significant for any measure. Although we hypothesized increased death-related anxiety, the absence of this effect may reflect a “cancelling out” of increasing concerns about death and dying in persons with terminal conditions [45, 46], relative to age-related declines in death anxiety that are typically observed in the general population [47,48,49,50]. The finding that depression and anxiety tend to be relatively stable across the HD disease spectrum would further support this premise [51]. In addition, the loss of motivation that is associated with increases in apathy that are typically seen over the disease course [51, 52] might further contribute to this “cancelling out” of increased concerns about death and dying that is borne out in the study results. Also, given that some literature has suggested the stability of EOL preferences [42,43,44], the absence of changes in EOL Planning in this study (especially in the absence of an intervention targeting EOL planning) may validate other research and demonstrate, for the first time, that EOL Planning for HD is relatively stable over the disease course. In addition, since HD progresses over a long period of time, changes in EOL attitudes and planning might be more detectable over time periods greater than 24 months.

There were some limitations to this study. First, as mentioned above, individuals with more advanced disease and those with higher CAG repeats [53] (which is indicative of more disease burden [54]), were more likely to drop out of the study, potentially making it more difficult to detect subtle change-over time in EOL concerns. Within the premanifest group, a large proportion of the sample had high disease burden (46.2%) and thus were closer in time to converting to manifest HD; therefore, group differences may be more prevalent between persons with manifest HD compared with individuals who are further from phenoconversion and who have not yet experienced early symptoms (i.e., behavioral or cognitive changes). Furthermore, given low proportion of racial and ethnic minorities in this sample, and higher rates of participants with high educational levels, it is unclear how findings might generalize to racial/ethnic minorities and individuals with lower educational attainment. We also did not examine other factors in these analyses that could account for some of the findings. For example, marital status and gender may impact EOL plans [55].

In summary, findings from this study support the clinical utility of the HDQLIFE EOL measures in persons with HD. The existing literature indicates that persons with HD do not engage their providers in discussions about EOL [7] and suggests that discussions about this can reduce family stress, anxiety, and depression [8,9,10]. These new assessment tools might be used to capture patient preferences about EOL. Ultimately, these types of PROs may help foster conversations between patients and providers on this difficult topic area. These measures would also be useful in clinical research targeting interventions to impact quality of life and promote EOL planning in the HD population.

References

The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group (1993) A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington's disease chromosomes. Cell 72:971–983

Ross CA, Margolis RL, Rosenblatt A, Ranen NG, Becher MW, Aylward E (1997) Huntington disease and the related disorder, dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA). Medicine (Baltimore) 76(5):305–338

Paulsen JS (2010) Early detection of Huntington disease. Future Neurol. https://doi.org/10.2217/fnl.09.78

Carlozzi NE, Tulsky DS (2013) Identification of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) issues relevant to individuals with Huntington disease. J Health Psychol 18(2):212–225

Carlozzi NE, Downing NR, McCormack MK et al (2016) New measures to capture end of life concerns in Huntington disease: meaning and purpose and concern with death and dying from HDQLIFE (a patient-reported outcomes measurement system). Qual Life Res 25:2403–2415

Carlozzi NE, Hahn EA, Frank SA et al (2018) A new measure for end of life planning, preparation, and preferences in Huntington disease: HDQLIFE end of life planning. J Neurol 265(1):98–107

Booij SJ, Tibben A, Engberts DP, Marinus J, Roos RA (2014) Thinking about the end of life: a common issue for patients with Huntington's disease. J Neurol 261(11):2184–2191

Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W (2010) The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 340:c1345

Voogt E, van der Heide A, Rietjens JA et al (2005) Attitudes of patients with incurable cancer toward medical treatment in the last phase of life. J Clin Oncol 23(9):2012–2019

Lyon ME, Jacobs S, Briggs L, Cheng YI, Wang J (2014) A longitudinal, randomized, controlled trial of advance care planning for teens with cancer: anxiety, depression, quality of life, advance directives, spirituality. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Society Adolesc Med 54(6):710–717

Carlozzi NE, Schilling SG, Lai JS et al (2016) HDQLIFE: development and assessment of health-related quality of life in Huntington disease (HD). Qual Life Res 25(10):2441–2455

Paulsen JS, Langbehn DR, Stout JC et al (2008) Detection of Huntington's disease decades before diagnosis: the Predict-HD study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79(8):874–880

Jackson WT, Ta N (1998) Effective serial measurement of cognitive orientation in rehabilitation: the orientation log. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 79(6):718–720

Gershon RC, Rothrock N, Hanrahan R, Bass M, Cella D (2010) The use of PROMIS and assessment center to deliver patient-reported outcome measures in clinical research. J Appl Meas 11(3):304–314

Zhang Y, Long JD, Mills JA, Warner JH, Lu WJ, Paulsen JS (2011) Indexing disease progression at study entry with individuals at-risk for Huntington disease. Am J Med Genet B 156B(7):751–763

Carlozzi N, Hahn EA, Frank S et al (2018) A new measure for end of life planning, preparation, and preferences in Huntington disease: HDQLIFE end of life planning. J Neurol 265:98–107

Choi SW, Podrabsky T, McKinney N (2012) Firestar-D: computerized adaptive testing simulation program for dichotomous item response theory models. Appl Psych Meas 36(1):67–68

Cella D, Lai JS, Nowinski CJ et al (2012) Neuro-QOL Brief measures of health-related quality of life for clinical research in neurology. Neurology 78(23):1860–1867

Cella D, Nowinski C, Peterman A et al (2011) The Neurology Quality of Life Measurement (Neuro-QOL) initiative. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 92(Suppl 1):S28–S36

Cella D, Riley W, Stone A et al (2010) The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol 63(11):1179–1194

Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N et al (2007) The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first 2 years. Med Care 45(5 Suppl 1):S3–S11

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B (2002) How to score version 2 of the SF-12 health survey (with a supplement documenting version 1), Quality Metrics, Lincoln

Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale (1996) reliability and consistency. Mov Disord 11(2):136–142

SAS Institute (2013) SAS 9.4 language reference concepts [computer program]. SAS Institute, Cary

Fisher RA (1922) On the interpretation of χ 2 from contingency tables, and the calculation of P. J Roy Stat Soc 85(1):8

Cronbach LG (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16:297–334

Andresen E (2000) Criteria for assessing the tools of disability outcomes research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81(12 Suppl 2):S15–20

Cramer D, Howitt DL (2004) The Sage dictionary of statistics. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Marder K, Zhao H, Myers RH et al (2000) Rate of functional decline in Huntington's disease. Neurology 54(2):452

Cohen R, Swerdlik M (2010) Psychological testing and assessment. McGraw-Hill, Burr Ridge

Tavakol M, Dennick R (2011) Post-examination analysis of objective tests. Med Teacher 33(6):447–458

Weir JP (2005) Quantifying test–retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res 19(1):231–240

Flansbjer U, Holmback AM, Downham D, Patten C, Lexell J (2005) Reliability of gait performance tests in men and women with hemiparesis after stroke. J Rehabil Med 37:75–82

Liaw L, Hsieh C, Lo S, Lee S, Lin J (2008) The relative and absolute reliability of two balance performance measures in chronic stroke patients. Disabil Rehabil 30(9):656–661

Forrest CB, Bevans KB, Tucker C et al (2012) Commentary: the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS-Æ) for children and youth: application to pediatric psychology. J Pediatr Psychol 37(6):614–621

Jones CM, Baker JN, Keesey RM et al (2018) Importance ratings on patient-reported outcome items for survivorship care: comparison between pediatric cancer survivors, parents, and clinicians. Qual Life Res 27(7):1877–1884

Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR et al (2007) Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 60(1):34–42

Hulur G, Hertzog C, Pearman A, Ram N, Gerstorf D (2014) Longitudinal associations of subjective memory with memory performance and depressive symptoms: between-person and within-person perspectives. Psychol Aging 29(4):814–827

Schilling OK, Wahl HW, Wiegering S (2013) Affective development in advanced old age: analyses of terminal change in positive and negative affect. Dev Psychol 49(5):1011–1020

Vogel N, Schilling OK, Wahl HW, Beekman AT, Penninx BW (2013) Time-to-death-related change in positive and negative affect among older adults approaching the end of life. Psychol Aging 28(1):128–141

Cohen-Mansfield J, Skornick-Bouchbinder M, Brill S (2018) Trajectories of end of life: a systematic review. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 73(4):564–572

van Wijmen MPS, Pasman HRW, Twisk JWR, Widdershoven GAM, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD (2018) Stability of end-of-life preferences in relation to health status and life-events: a cohort study with a 6-year follow-up among holders of an advance directive. PLoS ONE 13(12):e0209315

Auriemma CL, Nguyen CA, Bronheim R et al (2014) Stability of end-of-life preferences: a systematic review of the evidence. JAMA Int Medi 174(7):1085–1092

Wittink MN, Morales KH, Meoni LA et al (2008) Stability of preferences for end-of-life treatment after 3 years of follow-up: the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Arch Intern Med 168(19):2125–2130

Vehling S, Malfitano C, Shnall J et al (2017) A concept map of death-related anxieties in patients with advanced cancer. BMJ Support Palliat 7(4):427–434

Neel C, Lo C, Rydall A, Hales S, Rodin G (2015) Determinants of death anxiety in patients with advanced cancer. BMJ Support Palliat 5(4):373–380

Chopik WJ (2017) Death across the lifespan: age differences in death-related thoughts and anxiety. Death Stud 41(2):69–77

Cicirelli VG (2001) Personal meanings of death in older adults and young adults in relation to their fears of death. Death Stud 25(8):663–683

Reidick O, Schilling OK, Wahl H, Oswald F (2010) Attitudes towards dying and death in very old age: acceptance rather than anxiety? Gerontologist 50:390–390

Fortner BV, Neimeyer RA (1999) Death anxiety in older adults: a quantitative review. Death Stud 23(5):387–411

Thompson JC, Snowden JS, Craufurd D, Neary D (2002) Behavior in Huntington's disease: dissociating cognition-based and mood-based changes. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 14(1):37–43

Fritz NE, Boileau NR, Stout JC et al (2018) Relationships among apathy, health-related quality of life, and function in Huntington's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 30:194–201

Rosenblatt A, Abbott MH, Gourley LM et al (2003) Predictors of neuropathological severity in 100 patients with Huntington's disease. Ann Neurol 54(4):488–493

Moss DJH, Pardinas AF, Langbehn D et al (2017) Identification of genetic variants associated with Huntington's disease progression: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol 16(9):701–711

Cooney TM, Shapiro A, Tate CE (2019) End-of-life care planning: the importance of older adults' marital status and gender. J Palliat Med. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2018.0451

Acknowledgements

Work on this manuscript was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS077946) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000433). In addition, a portion of this study sample was collected in conjunction with the Predict-HD study. The Predict-HD study was supported by the NIH, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS040068), the NIH, Center for Inherited Disease Research (provided supported for sample phenotyping), and the CHDI Foundation (award to the University of Iowa). We thank the University of Iowa, the Investigators and Coordinators of this study, the study participants, the National Research Roster for Huntington Disease Patients and Families, the Huntington Study Group, and the Huntington’s Disease Society of America. We acknowledge the assistance of Jeffrey D. Long, Hans J. Johnson, Jeremy H. Bockholt, Roland Zschiegner, and Jane S. Paulsen. We also acknowledge Roger Albin, Kelvin Chou, and Henry Paulsen for the assistance with participant recruitment. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. HDQLIFE Site Investigators and Coordinators: Noelle Carlozzi, Praveen Dayalu, Stephen Schilling, Amy Austin, Matthew Canter, Siera Goodnight, Jennifer Miner, Nicholas Migliore (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI); Jane Paulsen, Nancy Downing, Isabella DeSoriano, Courtney Shadrick, Amanda Miller (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA); Kimberly Quaid, Melissa Wesson (Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN); Christopher Ross, Gregory Churchill, Mary Jane Ong (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD); Susan Perlman, Brian Clemente, Aaron Fisher, Gloria Obialisi, Michael Rosco (University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA); Michael McCormack, Humberto Marin, Allison Dicke, judy Rokeach (Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ); Joel S. Perlmutter, Stacey Barton, Shineeka Smith (Washington University, St. Louis, MO); Martha Nance, Pat Ede (Struthers Parkinson’s Center); Stephen Rao, Anwar Ahmed, Michael Lengen, Lyla Mourany, Christine Reece (Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH); Michael Geschwind, Joseph Winer (University of California – San Francisco, San Francisco, CA), David Cella, Richard Gershon, Elizabeth Hahn, Jin-Shei Lai (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Carlozzi, N.E. is supported by grant funding from the NIH, the Neilsen Foundation, and CHDI, as well as a government contract from the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services. She has previously provided patient-reported outcome measurement selection and application consultation for Teva Pharmaceuticals. She declares no conflicts of interest. Boileau, N.R. is supported by grant funding from the NIH, the Neilsen Foundation and CHDI. He declares no conflicts of interest. Paulsen, J.S. currently has research grants from the NIH; she is also supported by grant funding from NIH, NINDS, and CHDI; she declares no conflicts of interest. Perlmutter, J.S. currently has funding from the NIH, HDSA, CHDI, and APDA. He has received honoraria from the University of Rochester, American Academy of Neurology, Movement Disorders Society, Toronto Western Hospital, St. Lukes Hospital in St Louis, Emory U, Penn State, Alberta innovates, Indiana Neurological Society, Parkinson Disease Foundation, Columbia University, St. Louis University, Harvard University and the University of Michigan; he declares no conflicts of interest. Lai J.-S. currently has research grants from the NIH; she declares no conflicts of interest. Hahn, E.A. currently has research grants from the NIH; she is also supported by grant funding from the NIH and PCORI, and by research contracts from Merck and EMMES; she declares no conflicts of interest. McCormack, M.K. currently has grants from the NJ Department of Health; he declares no conflicts of interest. Nance, M.A. declares no conflicts of interest. Cella, D. receives grant funding from the National Institutes of Health and reports that he has no conflicts of interest. Barton, S.K. is supported by grant funding from the Huntington’s Disease Society of America, CHDI Foundation and the NIH. She declares no conflicts of interest. Downing, N.R. is supported by grant funding from the Health Resources and Services Administration and declares no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All data has been collected in accordance with local institutional review boards.

Informed consent

Study participants provided informed consent prior to the participation in study activities.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carlozzi, N.E., Boileau, N.R., Paulsen, J.S. et al. End-of-life measures in Huntington disease: HDQLIFE Meaning and Purpose, Concern with Death and Dying, and End of Life Planning. J Neurol 266, 2406–2422 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09417-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09417-7