Abstract

Introduction

It is very rare for split cord malformation to be associated with intraspinal teratoma, and it is even rarer for such tumors in the dorsal spine to extend into the mediastinum.

Case report

The authors describe a spinal teratoma with mediastinal extension in an 8-year-old boy who presented with 1-year history of backache. Neuroimaging revealed a heterogeneously enhancing intradural lesion from D2 to D7 levels with an extension into the mediastinum at the level of D4 vertebra. A split cord malformation type 2 and a cervical syrinx were also present. At surgery, a reddish-brown vascular tumor was present from D3 to D5 levels and was found to be going anteriorly into a defect in the body of D4 vertebra. Gross total excision of the intraspinal tumor was performed. Follow-up at 1 year revealed no recurrence or metastases.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first case of an intradural teratoma extending into the mediastinum, occurring concurrently with split cord malformation and other spinal anomalies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Primary intraspinal teratomas are rare tumors, and their association with split cord malformation (SCM) is even rarer [5, 6, 9 10, 13, 16, 17–19, 21, 26, 27, 33]. Extensive search of English literature revealed only one case of spinal teratoma which was extending into the mediastinum through the neural foramina [15]. We present a very rare case of a primary intradural teratoma of the dorsal spine extending into the mediastinum in a patient with SCM (type 2) and multiple congenital anomalies.

Case report

History and physical findings

This “normal born” 8-year-old right-handed boy presented with 1-year history of upper back pain and numbness below the clavicle. He had no history of weakness in any of his limbs or changes in his bowel or bladder habits. There was no history of trauma, and his developmental milestones were normal. The family history was unremarkable for any neurological disorders.

On physical examination, he was alert with normal higher mental functions. Cranial nerve examination was unremarkable. There was kyphoscoliosis of the upper thoracic spine with concavity to the right side. There was no tenderness. There was minimal weakness of bilateral grips. The upper limb deep tendon reflexes were normal. There was no weakness or wasting of the lower limbs, but the muscle tone was increased. The lower limb reflexes were exaggerated, and bilateral balbinski’s sign was present. A graded sensory loss to touch was present, with 10% loss at D1 dermatome to 50% loss at D7 and below. There was no evidence of c or any other neurocutaneous markers.

Neuroimaging

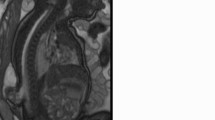

Plain x-ray of the cervico-dorsal spine revealed a kyphoscoliotic deformity with anomalous upper dorsal vertebra. There were butterfly vertebrae and a hole in the D4 vertebral body (Fig. 1). The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a heterogeneously enhancing intradural lesion at D2–7 levels. The isointense brightly enhancing component (D3–5) was extending into the mediastinum through a defect in the D4 vertebral body (Fig. 2a–d). The lesion was accompanied by SCM type 2 and syrinx in the cervical spinal cord.

MRI cervico-dorsal spine: saggital T1 (a), saggital gadolinum DTPA (b), axial T1 (c), axial gadolinum DTPA (d): heterogeneous intensity lesion D2–7 with isointense brightly enhancing (D3–5) component extending into the mediastinum through a defect in D4 vertebra, accompanied with dorsal split cord malformation type 2 and cervical syrinx

Surgery

Incision was given from C7 to D8 spinous processes, and laminoplasty of D1 to D7 vertebrae was performed using Midas Rex drill. On opening the dura, the arachnoid was markedly tense and bulging. A cyst containing thick mucinous fluid was decompressed. A reddish-brown, fleshy, vascular tumor was present from D3 to D5 levels anteriorly. It was suckable by Cavitron Ultrasonic Aspirator (CUSA) and was found going anteriorly into a defect in the body of D4 vertebra. A SCM type 2 was also present from D2 to D7 levels with the two hemicords splayed around the tumor. The spinal cord above the level of the SCM was dilated because of the presence of a syrinx, which was extending into the cervical region. Gross total excision of the intraspinal tumor was performed with removal from the vertebral defect and sealing of the defect with fascia and glue.

Postoperative course

The patient was continent and without any fresh neurological deficits at the time of discharge. At 1 1/2 years after surgery, he has regained full power of all four limbs. Muscle bulk and tone have returned to normal, and he is continuing his regular studies in school.

Neuropathological finding

Microscopic examination revealed an admixture of various tissues. There was mature adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, fibrocollagenous tissue, and mucous glands (Fig. 3a). At places, the lesion was composed of respiratory epithelium, which was pseudostratified and ciliated (Fig. 3b). Extensive search revealed no immature component. A final diagnosis of mature teratoma was entertained.

Discussion

Virchow was probably the first to describe an intraspinal teratoma containing connective tissue, fat, and cartilage [34]. A review of literature for such tumors is made difficult by the various terms used for cystic intraspinal lesions containing derivatives of more than one germ cell layers, such as teratomas, teratomatous cysts, cystic teratomas, teratoids, and cystic teratoid tumors [12, 16, 28, 29]. Several definitions of teratoma have been given. Bucy and Haymond suggested in 1932 that they represent an underdeveloped twin [4]. Sachs and Horrax in 1949 suggested that in many of these tumors, one or two germ layers tend to overgrow the others, and the total number of germ layers may be difficult to ascertain [30]. Smokers et al. agree that tumors with recognizable tissues from only two germ layers should be termed teratoids, and that only those tumors with identifiable tissues from all three germ layers should be termed teratomas [32]. The use of the term teratomatous cyst is unclear [16]. However, Furtado and Marques in 1951 claimed that the classification of tumors as mono-, bi- or tri-germinal merely represents “a confession of inadequate examination”, and multiple serial sections of the entire tumor would reveal derivatives from all three germ layers [8]. Poeze et al. agree that ectodermal and mesodermal elements may overgrow the endodermal elements, and it may be difficult to judge whether a particular tumor is a teratoid (multipotential origin) or teratoma (totipotential origin), and this division is somewhat arbitrary [24]. The definition of teratoma by Willis as “a true tumor or neoplasm composed of multiple tissues of kind foreign to the part in which it arises” has been used by authors in the past [35]. This definition does not require the presence of all germ layers to make the diagnosis of teratoma. However, the definition by Russell and Rubenstein in 1989 that a teratoma is a mass composed of derivatives of all three primitive germ layers, and mature and immature forms are distinguished on the basis of differentiation remains an accepted one [16].

Intraspinal teratomas are rarely occurring tumors. In a review of cases from Mayo clinic, Sloof et al. found only two cases in a series of 1,322 spinal tumors [31]. Black and German found only one case in a study of 142 intraspinal tumors [3]. Oi and Raimondi reported two cases of intradural extramedullary teratomas among 64 intraspinal neoplasms in children [20]. In their extensive review of literature in 1986, Smoker et al. found only 20 reported cases of intradural teratomas and observed that most of them are located in dorsal aspect of cervical or lower thoracic–upper lumbar regions [32]. Neurogenic tumors of the mediastinum are known to assume dumbbell shape and extend into the spinal canal [37]. There is only one case of an intraspinal teratoma with mediastinal extension [8]. This extensive tumor in a young infant was treated by laminotomies in a multistaged procedure. In our case, the thoracic intradural teratoma extended into the mediastinum through a congenital defect in the D4 vertebra.

Association of spinal teratomas with SCM is uncommon. Hader et al. found 15 cases of primary intraspinal teratomas associated with SCM [10].

Pang et al. have described a unified theory of embryogenePang et al. have described a unified theory of embryogenesis for all SCMs. At approximately the time sis for all SCMs. At approximately the time when primitive neuroenteric canal closes, formation of adhesions between ectoderm and endoderm leads an accessory neuroenteric canal formation. Endomesenchymal tract condenses around it and bisects the developing notochord and neural plate. The emerging split neural tube and the components of the endomesenchymal tract determine the configuration of the hemicords, the nature of median septum, the coexistence of various anomalies within the median cleft, and the high incidence of various myelodysplastic and cutaneous lesions [21, 22]. The pathogenesis of spinal teratomas is controversial and interesting. Sarraj et al. are of the view that they result from misplacement of multipotential primordial germ cells into the midline structures, after which they give rise to various germ cell tumors including teratomas [2]. This is suggested by the midline position of the lesions, intramedullary location of these lesions and sex chromatin studies which show that the nuclei of some of the epithilial cysts from male patients contain female chromatin [11, 13]. However, as this chromatin can represent XO in mosaic forms of nuclear chromatin, this evidence is called into question. Moreover, a germ cell origin only does not fully explain the usual midline location of the teratoma such as in mediastinum and diencephalon. It has also been suggested that spinal teratomas are hamartomatous lesions resulting from faulty excalation of notochordal plate from primitive foregut [7]. This could explain the common dorsal location of such tumors and frequent association of congenital anomalies of the spinal axis [5]. However, it does not explain the origin of tissues from more than one germ layer in teratoma. Koen et al. favor a dysembryogenic view [16]. The caudal cell mass of the developing embryo is an aggregate of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells that is pleuripotent in nature. They propose that the dysfunction of several regulatory genes of early neural development, along with aberrant inductive influences, induces these mesenchymal cells to give rise to teratomas [16]. However, in spite of these theories about etiopathogenesis of SCM and teratomas, it is not exactly known what common process gives rise to diastematomyelia and teratoma in a single patient.

We found 14 cases of spinal teratomas associated with SCMs (Table 1). The majority of these lesions were found in close proximity to diastematomyelia [10]. The presence of D2 to D7 SCM with D3 to D5 intradural teratoma in our patient is consistent with this finding. In 1984, McMaster reported that diastematomyelia was the most common anomaly (16.3%) in patients with congenital scoliosis. However, only one of his patients had an intradural teratoma [19].

Many osseous anomalies on plain x-rays have been reported in patients with SCMs, including scoliosis, bifid lamina, widened interpediculate distance, hemivertebra, bifid vertebra, fused vertebra, and narrowing of intervertebral disc space [2, 23, 36]. In our patient, there was a congenital defect in D4 vertebral body and butterfly vertebrae. MR is the investigation of choice for screening of SCMs. However, CT myelography is superior to MRI in defining the type of SCM that has been located [6]. Because the majority of patients have a tethering lesion unrelated to SCM, the whole spinal neuroaxis should be included in the screening MR image.

Surgery is the treatment of choice in intraspinal teratoma, as the diagnosis of benign or malignant cannot be made preoperatively [24]. Radical removal remains the ideal objective of surgery, but if they are located in highly functional areas of the cord and the tumor is tenaciously adherent to the spinal cord, a subtotal resection must be considered.

Recurrences after surgery were most often encountered in immature and malignant forms [14, 19]. Allsopp et al. observed that the local recurrences in 20 patients of intraspinal teratoma with a mean follow-up of 25 months were 10% in both subtotal and total resection groups [1]. It is unlikely that radiotherapy would benefit such slow growing tumors. They recommend that radiotherapy should be given only if histology shows any malignant germ cell elements, even after apparent total excision. The benefit of adjuvant radiotherapy has not been proven for benign teratomas, following either total or subtotal excision [25]. If recurrence occurs in such tumors, we should explore the possibility of further surgery first, before considering radiotherapy, which even then may have a doubtful efficacy. The role of monitoring of blood markers is limited as recurrences can take place from nonsecreting elements of the tumor [1]. The value of chemotherapy has not been fully explored.

References

Allsopp G, Sgouros S, Barber P, Walsh AR (2000) Spinal teratoma: is there a place for adjuvant treatment? Two cases and a review of the literature. Br J Neurosurg 14(5):482–488

Al-Sarraj ST, Parmar D, Dean AF, Phookun G, Bridgess LR (1998) Clinicopathological study of seven cases of spinal cord teratoma: a possible germ cell origin. Histopathology 32:51–56

Black SPW, German WJ (1950) Four congenital tumors found at operation within the vertebral canal, with observations on their incidence. J Neurosurg 7:49–61

Bucy PC, Haymond HE (1932) Lumbosacral teratoma associated with spina bifida occulta. Report of a case with review of literature. Am J Pathol 8:339–342

Cameron AH (1957) Malformations of the neuro-spinal axis, urogenital tract and foregut in spina bifida attributable to disturbances of the blastopore. J Pathol Bacteriol 73:213–221

Erhasin Y, Mutluer S, Kokamaan S, Demutas E (1998) Split spinal cord malformations in children. J Neurosurg 88:57–65

Fabinyl GCA, Adams JE (1979) High cervical spinal cord compression by an enterogenous cyst. J Neurosurg 51:556–559

Furtado D, Maarques V (1951) Spinal teratoma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 10:384–393

Garza-Mercado R (1983) Diastematomyelia and intramedullary epidermoid spinal cord tumor combined with extradural teratoma in an adult. J Neurosurg 58:954–958

Hader WJ, Steinbock P, Poskitt K, Hendson G (1989) Intramedullary spinal teratoma and diastematomyelia: case report and review of literature. Pediatr Neurosurg 30:140–145

Hoefnagel D, Benirschke K, Duarte J (1962) Teratomatous cyst within the vertebral canal observation on the occurrence of sex chromatin. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 25:159–164

Ingraham FB, Bailey OT (1946) Cystic teratomas and teratoid tumors of the central nervous system in infancy and childhood. J Neurosurg 3:511–532

Iskandar BJ, McLaughlin C, Oakes WJ (2000) Split cord malformations in myelomeningocele patients. Br J Neurosurg 14(3):200–203

Kamiya M, Tateyama H, Fujiyoshi Y, Tada T, Eimoto T, Shibata H, Hashizume Y (1991) Cerebrospinal fluid cytology in immature teratoma of the central nervous system: a case report. Acta Cytol 35:757–760

Kaneko M, Ohkawa H, Iwakawa M, Ikebukuro K (1999) Extensive epidural teratoma in early infancy treated by multistage surgery. Pediatr Surg Int 15:280–283

Koen JL, Mclendon RE, George TM (1998) Intradural spinal teratoma: evidence of a dysembrogenic origin. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg 89:844–851

Kumar R, Bansal KK, Chhabra DK (2001) Split cord malformation in paediatric patients: outcome of 19 cases. Neurol India 49:128–133

Lemmen LJ, Wilson CM (1951) Intramedullary malignant teratoma of the spinal cord: report of a case. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 66:61–68

McMaster MJ (1984) Occult intraspinal anomalies and congenital scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg 66a:584–601

Oi S, Raimondi AJ (1987) Hydrocephalus associated with intraspinal neoplasms in childhood. Am J Dis Child 135:1122–1124

Ozer H, Yuceer N (1989) Myelomeningocele, dermal sinus tract, split cord malformation associated with extradural teratoma in a 30-month-old girl. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 141:1123–1124

Pang D, Dias MS, Ahab-Barmada M (1992) Split cord malformation: Part 1: a unified theory of embryogenesis for double spinal cord malformations. Neurosurgery 31:451–480

Pang D (1992) Split cord malformations. Part 2: clinical syndrome. Neurosurgery 31:481–500

Poeze M, Herpers MJHM, Tjandra B, Freling G, Beuls EAM (1999) Intramedullary spinal teratoma presenting with urinary retention: case report and review of literature. Neurosurgery 45:379–385

Post KD, Stein BM (1995) Surgical management of spinal cord tumors and arteriovenous malformations. In: Schmidek HH, Sweet WH (eds) Operative neurosurgical techniques. Indications, methods and results, 3rd edn. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 2027–2048

Razack N, Page LK (1995) Split notochord syndrome: case report. Neurosurgery 37:1006–1008

Reddy CRRM, Chalapathi KV, Jagabhandhu N (1968) Intraspinal teratoma associated with diastematomyelia. Indian J Pathol Bacteriol 11:77–81

Rewcastel NB, Francoeur J (1964) Teratomatous cysts of the spinal cord: with sex chromatin studies. Arch Neurol 11:91–99

Rosenbaum TJ, Soule EH, Onofrio BM (1978) Teratomatous cysts of the spinal canal: case report. J Neurosurg 49:292–297

Sachs E, Horrax G (1949) A cervical and a lumbar pilonidal sinus communicating with intraaspinal dermoids. J Neurosurg 6:97–112

Sloof JL, Kernohan JW, McCarty CS (1964) Primary intramedullary tumors of the spinal cord and filum terminale. WB Saunders, Philadelphia

Smoker WRK, Biller J, Moore SA, Beck DW, Hart MN (1986) Intradural spinal teratoma: case report and review of literature. Am J Neuroradiol 7:905–910

Ugarte N, Gonzalez-Crussi F, Sotelo-Avila C (1980) Diastematomyelia associated with teratomas. J Neurosurg 53:720–725

Virchow R (1863) Die Krankhaften Geschwulste, vol 1. Hirschwald, Berlin, p 514

Willis RA (1962) The borderland of embryology and pathology. Butterworths, London, pp 442–462

Winter RB, Haven JJ, Moe JH et al (1974) Diastematomyelia and congenital spine deformities. J Bone Joint Surg Am 56:27–39

Yuksel M, Pamir N, Ozer F, Batirel HF, Ercan S (1996) The principles of surgical management in dumbbell tumors. Eur J Cardio-thorac Surg 10(7):569–573

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Suri, A., Ahmad, F.U., Mahapatra, A.K. et al. Mediastinal extension of an intradural teratoma in a patient with split cord malformation: case report and review of literature. Childs Nerv Syst 22, 444–449 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-005-1240-3

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-005-1240-3