Abstract

The clinical and pathological findings of plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) have been described in the literature but the etiology is not well established, and treatment options are poorly defined. We reviewed patients with PBL in our institution to characterize the clinicopathologic features in our patient population. In this retrospective analysis from a single academic institution, five patients with PBL were identified and analyzed. Human immunodeficiency virus and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) were identified in 40% (two out of five) and 80% (four out of five) of these patients, respectively. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement was identified in four out of five (80%) patients. Interestingly, three out of five patients had a concurrent or preceding second primary malignancy including small lymphocytic lymphoma, endometrial cancer, and nonsmall cell lung cancer. Most of the patients had advanced disease and a poor performance status at diagnosis. Only two of the patients received systemic chemotherapy with an initial partial response. All five patients died; the median overall survival was 1 month. Our experience in patients with PBL indicates that CNS involvement is more common than reported in the literature. Coexistence of a second primary malignancy may be frequent, and prognosis remains dismal with standard lymphoma therapy. Lastly, the role of HHV-8 in the etiopathogenesis needs further trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of adult non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) and comprises about a third of these neoplasms [11]. Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is considered a subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by the World Health Organization (WHO) classification system [21].

PBL is a rare form of NHL that was once thought to occur almost exclusively in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive individuals [10, 12, 14, 16, 46, 47]. More recently, however, it has been described in HIV-negative patients [27, 30, 33, 46]. This lymphoma has a predilection for extranodal involvement, particularly the oral cavity mucosa [3, 4, 6, 10, 14, 18, 21, 35, 41]. Involvement of several extraoral primary sites has been reported [9, 16, 28, 30, 36]. These tumors are characterized by large blastic cells with plasmacytoid differentiation contributing to their designation as PBL [12, 14, 47]. The tumor cells are typically positive for plasma cell markers such as cluster designation (CD)38 and CD138 and are often negative for leukocyte common antigen (LCA). Variable expression of CD79a, with cytoplasmic light chain restriction and immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement, have been shown in PBL [14]. Though PBL is considered to be of differentiated B-cell lineage, they are negative for other common B-cell markers such as CD20 and PAX-5. Positivity for postgerminal center B-cell marker multiple myeloma-1 (MUM1)/RF4 has also been reported [47].

Here, we discuss the clinicopathologic features of five patients with PBL as well as their clinical outcomes. Our experience with these patients revealed some clinically important results. Firstly, CNS involvement is more common than reported in the literature and therefore requires extensive evaluation. Secondly, coexistence of a second primary malignancy may be frequent. We also demonstrated the high rate of human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) positivity (four out of five, 80%), raising the possibility of HHV-8 in the etiopathogenesis of PBL, which has been controversial. Lastly, the prognosis for these patients is quite poor with standard lymphoma therapy particularly when they present with widespread disease.

Materials and methods

In this retrospective analysis, we identified five patients that met the WHO criteria for PBL and were diagnosed and treated at the Medical College of Georgia (MCG) between 2000 and 2007. The MCG Institutional Review Board approved the study. There were three female and two male patients. The median age of these patients was 44 years (range, 38 to 55 years) at the time of diagnosis of PBL.

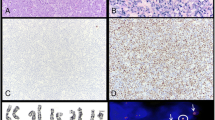

Histologic sections were prepared in a standard fashion, cut 3-μm thick, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Immunohistochemical stains were performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue after antigen retrieval in citrate buffer. The slides were incubated in an automated stainer with monoclonal antibodies directed against LCA, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), MUM1 antigen, CD antigens CD30, CD79a, CD20, CD3, CD5, CD138, PAX5, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) 1, kappa, and lambda (Table 1). Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) genome was also tested for in all five cases using the in situ hybridization technique (ISH). This was used to detect the EBV-encoded RNA (EBER1 and 2) on paraffin-embedded tissues. Slides were deparaffinized, rehydrated, digested with proteinase K, and hybridized with the probes for 90 min. EBV-negative and EBV-positive lymphoid tissue controls were also prepared. HHV-8 was performed on all cases. Four-micron sections were cut from paraffin blocks and mounted on treated slides (Superfrost plus, VWR Scientific Products, Suwanee, GA, USA). Slides were air dried over night, then placed in a 60° oven for 30 min. Slides were deparaffinized then run through graded alcohols to distilled water. Slides were pretreated with Target Retrieval Solution pH 6.0 (Dako Corp, Carpinteria, CA, USA) using a steamer (Black and Decker rice steamer) and slides rinsed in distilled water. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched with 0.3% H2O2 in distilled water for 5 min followed by distilled water for 2 min and placed in 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min. Slides were incubated with primary antibody HHV-8 (rat; ABCAM, Cambridge, MA, USA) 1:50 for 30 min at room temperature followed by two changes of 1× PBS. Slides were incubated with a peroxidase-conjugated AffiniPure(F(ab’) Fragment Donkey antirat IgG (H&L); Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA, USA at 1:100 for 1 h, rinsed in two changes of 1× PBS. Bound antibody was detected with DAB substrate kit (Dako-DAB substrate kit for peroxidase—HRP, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI, USA). HHV-8 staining was scored using a scoring system based on distribution and intensity of staining. A score of “0” for intensity was characterized by no staining, 1+ score corresponded to weak staining intensity, 2+ score to moderate intensity, and a 3+ score to strong intensity. HHV-8 staining distribution was scored as 1+ for 0–10% cells showing positive staining, 2+ for 10–50%, 3+ for 50–75%, and 4+ >75% showing positive staining.

Results

Patient- and disease-related findings at diagnosis, treatment, and clinical outcomes are presented in Table 1. Results of immunohistochemistry and ISH studies are summarized in Table 2. HHV-8 revealed nuclear staining and the intensity and percentage of cells staining is summarized in Table 3. A detailed description of each patient is presented as a separate case report below.

Case 1

A 55-year-old African-American female developed endometrial adenocarcinoma (stage IIIC) and treated with a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Six months later, she developed weakness in the right leg due to a large pelvic mass. Biopsy of the mass revealed sheets of atypical lymphoid cells with immature chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Some of the cell had a plasmacytoid features. The tumor cells were strongly positive for CD138 and negative for CD20, EMA, and pankeratin. The morphologic and immunophenotypic findings were consistent with PBL. Metastatic carcinoma was excluded based on histology and the negative pankeratin and EMA staining. Cytogenetic studies revealed complex abnormalities [t(X;1)(q28;q21), t(2;10)(q21;p13), inv(9) (p11q13), t(12;15)(q13;q22), del(16)(q13q22), +20,der(22)]. A small M-spike was noted on serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP); immunofixation electrophoresis revealed the presence of a monoclonal free lambda light chain. Bone marrow (BM) biopsy was negative for lymphoma. The patient received bortezomib (1.3 mg/m2/day, days 1, 4, 8) and dexamethasone (40 mg/day, days 1–4) but died of multiorgan failure 25 days after hospital admission.

Case 2

A 54-year-old Caucasian female developed right groin mass, night sweats, and weight loss, dyspnea, worsening headache, and altered mental status. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain demonstrated multiple enhancing lesions, the largest was in the right frontal lobe extending to the orbitofrontal distribution with midline left shift. Chest X-ray revealed a large left upper lobe lung mass. A brain biopsy revealed a proliferation of atypical lymphoid cells with immature chromatin some of which had a plasmacytoid appearance (Fig. 1). The tumor cells were positive for CD138 (Fig. 2), EMA, PAX-5, and HHV-8 (Fig. 3) and negative for CD20, CD79a, CK7, CK20, and TTF-1. The morphologic and immunophenotypic findings were consistent with PBL. Again, metastatic carcinoma was excluded based on the histology and immunophenotype. BM biopsy was negative for involvement by lymphoma. Karyotyping of the brain mass was unsuccessful.

On the third day of hospitalization, the patient became unresponsive and was intubated. High-dose dexamethasone and a single treatment of whole brain irradiation were initiated but the patient died immediately. An autopsy revealed a second primary lung malignancy, consistent with poorly differentiated nonsmall cell carcinoma.

Case 3

A 38-year-old African-American male, with an 8-year history of HIV/AIDS, presented with complaints of blurred vision. His physical exam was pertinent for palsies of cranial nerves III and V. SPEP revealed an M-spike of 2.4 g/dL. The patients CD4 count was 94 cells/μL and the HIV viral load was 3,959 copies/mL. MRI revealed a mass in the paranasal sinuses extending into the anterior skull base. An endonasal biopsy revealed a necrotic tumor composed of large plasmacytoid lymphoid cells with immature nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Cytogenetic studies revealed a t(8;14) translocation. BM biopsy revealed involvement by PBL. The patient rapidly deteriorated and died on hospital day 12 despite high-dose steroid treatment.

Case 4

A 44-year-old Caucasian female, with a 10-year history of HIV, presented with fatigue, dyspnea, night sweats, and headache. The patient had discontinued highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) 3 years prior to presentation. Physical examination revealed a large left neck mass as well as hepatomegaly. Computerized tomography (CT) scan revealed multiple homogenously enhancing lymph nodes in the cervical region, hepatomegaly, and enlarged kidneys. MRI of the brain demonstrated increased signal within the periventricular subcortical white matter, bilateral frontal lobes, inferior caudate nuclei, and bilateral external capsules. Biopsy of the left neck mass revealed PBL. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was positive for lymphoma. BM biopsy was negative for involvement by PBL.

The patient was treated with etoposide, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (EPOCH) and intrathecal (IT) methotrexate. HAART was started concomitantly. The patient completed two cycles of EPOCH and three doses of IT methotrexate with dramatic initial improvement but developed Aspergillus fumigatus pneumonia. Antifungal therapy was started and chemotherapy was held, resulting in disease progression. The patient died in 6 months.

Case 5

A 42-year-old male presented with a 6-week history of dyspnea, facial swelling, and night sweats. CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed complete occlusion of the superior vena cava (SVC) with collateral vessels around the chest wall, massive mediastinal and abdominal lymphadenopathy, and right pleural metastases. There was no M-spike in the serum or urine. An MRI of the brain was negative for abnormal leptomeningeal enhancement.

A biopsy of the mediastinal mass revealed PBL. The BM was positive for involvement by PBL. A separate aggregate of small lymphocytes positive for CD20 and coexpressing CD5 with lambda light chain restriction was detected in the BM biopsy. There was no evidence of peripheral blood lymphocytosis. Therefore, we favored concurrent bone marrow involvement by small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL). The mediastinal mass biopsy was small and a low grade component was not identified outside the bone marrow. Cytogenetics on the BM revealed two related abnormal clones with t(9;11) and del(16). The SVC syndrome was emergently treated with mediastinal radiation and high-dose steroids. He was subsequently started on cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone followed by hyper-CVAD (high-dose cytarabine and methotrexate) therapy. The patient also received CNS prophylaxis with IT cytarabine due to the high risk of CNS involvement (i.e., positive BM involvement). While receiving the second dose of IT chemotherapy, CSF analysis revealed plasmablasts. The patient progressed on treatment died in 4 months.

Discussion

Immunosuppressive conditions are clearly associated with PBL. Though the etiology of PBL is not clearly defined, its predilection for HIV-positive patients is well established in the literature and it has also been reported in solid organ transplant patients requiring immunosuppressive therapy [2, 9, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 46–48]. Only two of our five patients were found to be HIV positive. In addition to HIV, other viruses including Epstein–Barr virus and HHV-8 have been evaluated in the etiopathogenesis of PBL [7, 10, 14–16, 46]. Delecluse et al. reported presence of EBV in nine of 15 tumors (60%) and Teruya-Feldstein et al. found EBER positivity in six of ten cases (60%) [14, 46]. The absence of EBV in a third of the cases suggests that it is not likely the sole etiologic agent and other factors are involved. Vega et al. observed that EBER positivity was seen exclusively in PBL (five of five cases) and in none of the plasmablastic plasma cell myelomas (zero of seven cases). In their experience, this was the only statistically significant parameter that distinguished these two neoplasms which often have overlapping morphologic features [47]. EBER was found to be positive in only one of five (20%) of our patients. On the other hand, HHV-8 was positive in four of five patients (80%). The association of HHV-8 with primary effusion lymphoma, multicentric Castleman disease (MCD), and MCD-associated PBL is well established [17, 20, 22, 29, 44, 45]. None of our patients had evidence of MCD. Evidence supporting a pathogenetic role for HHV-8 in promoting tumor formation in patients with HIV infection is thought to be mediated by viral interleukin 6 which may provide a potent mitogenic stimulus resulting in enhanced proliferation of HIV in patients coinfected with both viruses [8, 25, 44]. However, the role of HHV-8 in the etiology of PBL is controversial as there are studies reporting both a high as well as low incidence of this virus in these cases [7, 15, 47]. Our study suggests a possible role for HHV-8 as a lymphomagenic agent and further studies should be done to confirm the role of HHV-8 as one of the causal agents of PBL.

Cytogenetic analyses were heterogeneous in our patients. PAX-5, RHO/TTF, PIM1, and MYC molecular pathways are found to be involved in AIDS-related lymphomas [5]. There are no well-known recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities described in PBL but t(8;14) has been described [13]. In one of our patients (case 3), t(8;14) was detected, which may have contributed his poor outcome.

More interestingly, CNS involvement in patients in PBL has not been emphasized in the literature. In the report by Teruya-Feldstein, eight of 12 patients with negative CSFs received IT chemotherapy for CNS prophylaxis [46]. One of these eight patients (8%) relapsed with CNS disease. This patient has stage IV disease and was HIV negative. Riedel et al. also reported a case of oral PBL in an HIV-positive patient who relapsed with CNS involvement and died [41]. In our center, four of five patients (80%) were found to have CNS involvement by PBL. The patients with CNS involvement either had advanced stage disease, i.e., BM involvement or had tumor in a site adjacent to the CNS (e.g., maxillary sinus and neck). Primary PBL in the CNS has been recently reported in an HIV-positive patient [43].

Three out of five patients had either a concurrent or a preceding second malignancy and there are a few similar reports in the literature [19, 23, 42]. All three patients with second malignancies were HIV negative. All five cases had touch preparations or smears for evaluation. We found that cytologic features were extremely useful in differentiating PBL from poorly differentiated carcinoma as the plasmacytoid features were more readily apparent on the smears than the H&E sections [40]. A preceding solid tumor malignancy may result in an immune deficient status predisposing patient to PBL. Of interest, one case of PBL representing Richter transformation of an indolent lymphoproliferative disorder has been reported [42]. In this case report, the patient had been heavily treated with cladarabine (2-CdA) for chronic lymphocytic leukemia/SLL and the PBL arose in a setting of prolonged immunosuppression. In our report, case 5 had coexisting SLL and PBL that was diagnosed at the same time with no prior treatment with rituximab or immunosuppressive therapy for the low-grade lymphoma. A clonal relationship could not be established by molecular studies in this case but both the SLL and PBL were lambda light chain restricted; therefore, this is not entirely excluded. We do favor the PBL to be a form of Richter’s transformation. The details of this patient are described elsewhere [37].

The clinical behavior of PBL is highly aggressive with a poor response to therapy and a short overall survival (OS). There are no established treatment regimens for PBL patients, and most patients receive multiagent systemic chemotherapy or local irradiation alone [14, 24, 30, 34, 41, 46]. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant has been reported to be successful in a single case report [13]. The impact of HAART on overall survival in HIV-positive patients with NHL appears to be positive [1, 24, 26, 31, 32, 34, 38, 39]. Long-term survivors and spontaneous regression of NHL in patients on HAART alone have been but anecdotal [1, 32]. In a study by Teruya-Feldstein et al., HIV-negative patients with PBL appeared to have a worse prognosis (median survival of 12 months) compared to their HIV-positive counterparts receiving HAART (median survival not reached at 22 months of follow-up) [46]. Three out of our five patients could not receive chemotherapy due to poor performance status. Two patients received systemic and IT chemotherapy with a short-term response. All five patients progressed despite treatment and died. Our patients had a shorter OS (1 month) than reported (median OS of 6 to 12 months) [12, 14] which might have resulted from having advanced disease and poor performance status at diagnosis, association with a second primary malignancy, CNS involvement, and advanced AIDS. Given the poor outcome with standard chemotherapy for DLBCL and some common features with plasma cell dyscrasias, bortezomib, or lenalidomide might be considered in prospective trials in the treatment of PBL [39].

In conclusion, patients with PBL present with heterogeneous clinical presentations. In our experience, CNS involvement is quite common and must be diligently evaluated in all cases and treated with IT chemotherapy, as appropriate. The coexistence of other malignancies should be considered during evaluation of these patients. Causal relationship of HHV-8 with PBL should be further evaluated. As there is no established standard treatment for PBL and the prognosis remains poor, novel agents should be evaluated in prospective trials for these uncommon yet fatal lymphomas.

References

Armstrong R, Bradrick J, Liu YC (2007) Spontaneous regression of an HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma in the oral cavity: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 65(7):1361–1364. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2005.12.039

Borenstein J, Pezzella F, Gatter KC (2007) Plasmablastic lymphomas may occur as post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Histopathology 51(6):774–777. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02870.x

Borrero JJ, Pujol E, Perez S, Merino D, Montano A, Rodriguez FJ (2002) Plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity and jaws. AIDS 16(14):1979–1980. doi:10.1097/00002030-200209270-00022

Brown RS, Campbell C, Lishman SC, Spittle MF, Miller RF (1998) Plasmablastic lymphoma: a new subcategory of human immunodeficiency virus-related non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 10(5):327–329. doi:10.1016/S0936-6555(98)80089-7

Carbone A (2003) Emerging pathways in the development of AIDS-related lymphomas. Lancet Oncol 4(1):22–29. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(03)00957-4

Carbone A, Gloghini A, Gaidano G (2004) Is plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity an HHV-8-associated disease? Am J Surg Pathol 28(11):1538–1540. author reply 1540. doi:10.1097/01.pas.0000131533.21345.1c

Carbone A, Gloghini A, Gaidano G (2008) KSHV/HHV8 doesn’t play a significant role in the development of plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity. Am J Surg Pathol 32(1):172–174

Chatterjee M, Osborne J, Bestetti G, Chang Y, Moore PS (2002) Viral IL-6-induced cell proliferation and immune evasion of interferon activity. Science 298(5597):1432–1435. doi:10.1126/science.1074883

Chetty R, Hlatswayo N, Muc R, Sabaratnam R, Gatter K (2003) Plasmablastic lymphoma in HIV+ patients: an expanding spectrum. Histopathology 42(6):605–609. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2559.2003.01636.x

Cioc AM, Allen C, Kalmar JR, Suster S, Baiocchi R, Nuovo GJ (2004) Oral plasmablastic lymphomas in AIDS patients are associated with human herpesvirus 8. Am J Surg Pathol 28(1):41–46. doi:10.1097/00000478-200401000-00003

The Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project (1997) A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood 89(11):3909–3918

Colomo L, Loong F, Rives S, Pittaluga S, Martinez A, Lopez-Guillermo A et al (2004) Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with plasmablastic differentiation represent a heterogeneous group of disease entities. Am J Surg Pathol 28(6):736–747. doi:10.1097/01.pas.0000126781.87158.e3

Dawson MA, Schwarer AP, McLean C, Oei P, Campbell LJ, Wright E et al (2007) AIDS-related plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity associated with an IGH/MYC translocation–treatment with autologous stem-cell transplantation in a patient with severe haemophilia-A. Haematologica 92(1):e11–e12. doi:10.3324/haematol.10933

Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, Hummel M, Marafioti T, Schneider U et al (1997) Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood 89(4):1413–1420

Deloose ST, Smit LA, Pals FT, Kersten MJ, van Noesel CJ, Pals ST (2005) High incidence of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection in HIV-related solid immunoblastic/plasmablastic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia 19(5):851–855. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2403709

Dong HY, Scadden DT, de Leval L, Tang Z, Isaacson PG, Harris NL (2005) Plasmablastic lymphoma in HIV-positive patients: an aggressive Epstein–Barr virus-associated extramedullary plasmacytic neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol 29(12):1633–1641. doi:10.1097/01.pas.0000173023.02724.1f

Dupin N, Diss TL, Kellam P, Tulliez M, Du MQ, Sicard D et al (2000) HHV-8 is associated with a plasmablastic variant of Castleman disease that is linked to HHV-8-positive plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood 95(4):1406–1412

Flaitz CM, Nichols CM, Walling DM, Hicks MJ (2002) Plasmablastic lymphoma: an HIV-associated entity with primary oral manifestations. Oral Oncol 38(1):96–102. doi:10.1016/S1368-8375(01)00018-5

Foltyn W, Kos-Kudla B, Sieminska L, Zemczak A, Strzelczyk J, Marek B et al (2006) Unique case of caecum plasmablastic lymphoma CD138(+) in patient with late diagnosed colon neuroendocrine carcinoma. Endokrynol Pol 57(2):160–165

Gessain A, Sudaka A, Briere J, Fouchard N, Nicola MA, Rio B et al (1996) Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes-like virus (human herpesvirus type 8) DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman’s disease: is there any relevant association in non-human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients? Blood 87(1):414–416

Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW (2001) Tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. IARC, Lyon

Jenner RG, Maillard K, Cattini N, Weiss RA, Boshoff C, Wooster R et al (2003) Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-infected primary effusion lymphoma has a plasma cell gene expression profile. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100(18):10399–10404. doi:10.1073/pnas.1630810100

Kuhnen C, Schneele H, Muller KM (1994) Malignant lymphoma and colon carcinoma 3 years after heart transplantation and immunosuppression. Pathologe 15(2):129–133. doi:10.1007/s002920050036

Lester R, Li C, Phillips P, Shenkier TN, Gascoyne RD, Galbraith PF et al (2004) Improved outcome of human immunodeficiency virus-associated plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: a report of two cases. Leuk Lymphoma 45(9):1881–1885. doi:10.1080/10428190410001697395

Li H, Wang H, Nicholas J (2001) Detection of direct binding of human herpesvirus 8-encoded interleukin-6 (vIL-6) to both gp130 and IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) and identification of amino acid residues of vIL-6 important for IL-6R-dependent and -independent signaling. J Virol 75(7):3325–3334. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.7.3325-3334.2001

Lim ST, Karim R, Nathwani BN, Tulpule A, Espina B, Levine AM (2005) AIDS-related Burkitt’s lymphoma versus diffuse large-cell lymphoma in the pre-highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and HAART eras: significant differences in survival with standard chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 23(19):4430–4438. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.11.973

Lin F, Zhang K, Quiery AT Jr, Prichard J, Schuerch C (2004) Plasmablastic lymphoma of the cervical lymph nodes in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 128(5):581–584

Lin O, Gerhard R, Zerbini MC, Teruya-Feldstein J (2005) Cytologic features of plasmablastic lymphoma. Cancer 105(3):139–144. doi:10.1002/cncr.21036

Liu W, Lacouture ME, Jiang J, Kraus M, Dickstein J, Soltani K et al (2006) KSHV/HHV8-associated primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma in a patient with Castleman’s disease and Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Cutan Pathol 33(Suppl 2):46–51. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00539.x

Masgala A, Christopoulos C, Giannakou N, Boukis H, Papadaki T, Anevlavis E (2007) Plasmablastic lymphoma of visceral cranium, cervix and thorax in an HIV-negative woman. Ann Hematol 86(8):615–618. doi:10.1007/s00277-007-0280-z

Matthews GV, Bower M, Mandalia S, Powles T, Nelson MR, Gazzard BG (2000) Changes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Blood 96(8):2730–2734

Nasta SD, Carrum GM, Shahab I, Hanania NA, Udden MM (2002) Regression of a plasmablastic lymphoma in a patient with HIV on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Leuk Lymphoma 43(2):423–426. doi:10.1080/10428190290006260

Nguyen DD, Loo BW Jr, Tillman G, Natkunam Y, Cao TM, Vaughan W et al (2003) Plasmablastic lymphoma presenting in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient: a case report. Ann Hematol 82(8):521–525. doi:10.1007/s00277-003-0684-3

Panos G, Karveli EA, Nikolatou O, Falagas ME (2007) Prolonged survival of an HIV-infected patient with plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity. Am J Hematol 82(8):761–765. doi:10.1002/ajh.20807

Porter SR, Diz Dios P, Kumar N, Stock C, Barrett AW, Scully C (1999) Oral plasmablastic lymphoma in previously undiagnosed HIV disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 87(6):730–734. doi:10.1016/S1079-2104(99)70170-8

Pruneri G, Graziadei G, Ermellino L, Baldini L, Neri A, Buffa R (1998) Plasmablastic lymphoma of the stomach. A case report. Haematologica 83(1):87–89

Ramalingam P, Nayak-Kapoor A, Reid-Nicholson M, Crawford J, Ustun C (2008) Plasmablastic lymphoma with small lymphocytic lymphoma: clinico-pathologic features, and review of the literature. Leuk Lymphoma 18:1–4

Ratner L, Lee J, Tang S, Redden D, Hamzeh F, Herndier B et al (2001) Chemotherapy for human immunodeficiency virus-associated non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in combination with highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Oncol 19(8):2171–2178

Reece DE (2007) Management of multiple myeloma: the changing landscape. Blood Rev 21(6):301–314. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2007.07.001

Reid-Nicholson M, Kavuri S, Ustun C, Crawford J, Nayak-Kapoor A, Ramalingam P (2008) Plasmablastic lymphoma: cytologic findings in 5 cases with unusual presentation. Cancer (in press)

Riedel DJ, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Zhao XF, Redfield RR, Gilliam BL (2008) Plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity: a rapidly progressive lymphoma associated with HIV infection. Lancet Infect Dis 8(4):261–267. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70067-7

Robak T, Urbanska-Rys H, Strzelecka B, Krykowski E, Bartkowiak J, Blonski JZ et al (2001) Plasmablastic lymphoma in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia heavily pretreated with cladribine (2-CdA): an unusual variant of Richter’s syndrome. Eur J Haematol 67(5–6):322–327. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0609.2001.00592.x

Shuangshoti S, Assanasen T, Lerdlum S, Srikijvilaikul T, Intragumtornchai T, Thorner PS (2007) Primary central nervous system plasmablastic lymphoma in AIDS. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 34:245–247

Song J, Ohkura T, Sugimoto M, Mori Y, Inagi R, Yamanishi K et al (2002) Human interleukin-6 induces human herpesvirus-8 replication in a body cavity-based lymphoma cell line. J Med Virol 68(3):404–411. doi:10.1002/jmv.10218

Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, Cacoub P, Cazals-Hatem D, Babinet P et al (1995) Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman’s disease. Blood 86(4):1276–1280

Teruya-Feldstein J, Chiao E, Filippa DA, Lin O, Comenzo R, Coleman M et al (2004) CD20-negative large-cell lymphoma with plasmablastic features: a clinically heterogenous spectrum in both HIV-positive and -negative patients. Ann Oncol 15(11):1673–1679. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdh399

Vega F, Chang CC, Medeiros LJ, Udden MM, Cho-Vega JH, Lau CC et al (2005) Plasmablastic lymphomas and plasmablastic plasma cell myelomas have nearly identical immunophenotypic profiles. Mod Pathol 18(6):806–815. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800355

Verma S, Nuovo GJ, Porcu P, Baiocchi RA, Crowson AN, Magro CM (2005) Epstein–Barr virus- and human herpesvirus 8-associated primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma in the setting of renal transplantation. J Cutan Pathol 32(1):35–39. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2005.00258.x

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge Teresa Coleman, MD and David Deremer, Pharm D for their contribution in editing the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ustun, C., Reid-Nicholson, M., Nayak-Kapoor, A. et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma: CNS involvement, coexistence of other malignancies, possible viral etiology, and dismal outcome. Ann Hematol 88, 351–358 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-008-0601-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-008-0601-x