Abstract

Background

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathways are now implemented worldwide with strong evidence that adhesion to such protocol reduces medical complications, costs and hospital stay. This concept has been applied for pancreatic surgery since the first published guidelines in 2012. This study presents the updated ERAS recommendations for pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) based on the best available evidence and on expert consensus.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted in three databases (Embase, Medline Ovid and Cochrane Library Wiley) for the 27 developed ERAS items. Quality of randomized trials was assessed using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement checklist. The level of evidence for each item was determined using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation system. The Delphi method was used to validate the final recommendations.

Results

A total of 314 articles were included in the systematic review. Consensus among experts was reached after three rounds. A well-implemented ERAS protocol with good compliance is associated with a reduction in medical complications and length of hospital stay. The highest level of evidence was available for five items: avoiding hypothermia, use of wound catheters as an alternative to epidural analgesia, antimicrobial and thromboprophylaxis protocols and preoperative nutritional interventions for patients with severe weight loss (> 15%).

Conclusions

The current updated ERAS recommendations for PD are based on the best available evidence and processed by the Delphi method. Prospective studies of high quality are encouraged to confirm the benefit of current updated recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) is a multimodal pathway that has been widely introduced to reduce the surgical stress and improve recovery after major surgery. It is now validated in many types of surgery since it reduces postoperative medical complications, hospital stay and costs [1,2,3]. First guidelines for pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) were published in 2012 [4]. A recent meta-analysis confirmed the positive impact of ERAS on postoperative recovery after PD [5].

The present systematic review elaborates the updated ERAS Society guidelines for enhanced recovery after PD by systematic review of the literature and expert consensus with the Delphi method.

Methods

Literature search and data selection

A systematic literature search was conducted with the assistance of a medical librarian in four databases (Embase, PubMed, Medline Ovid and Cochrane Library Wiley) for the 27 developed items. Terms related to pancreatoduodenectomy were combined with terms related to each item. Thesaurus terms and free terms were identified after analysis of the 2012 guideline [4]. The period search was from January 2000 to December 2018. Only full-text articles in English were analyzed. Eligible articles included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or prospective cohort studies with control group. Retrospective series were considered only if data of better quality could not be identified. For the items where no specific data in pancreatic surgery were available, results were extrapolated from other types of abdominal surgery. Following the searches, all identified citations were collated into a citation management software (Endnote X8). The quality of RCTs included was assessed using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement checklist [6]. The level of evidence for each item was determined using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system, in which the level of evidence was classified as high, moderate, low or very low [7]. The research team (EM, ND) made a final decision on inclusion of a study or not and was responsible for drafting the first manuscript.

Modified delphi process

As previously performed for the ERAS guidelines for liver surgery, a three-round Web-based Delphi approach was used in this consensus process [8, 9]. Each expert was asked to write one up to four items chapters and a recommendation according to the literature search. Once all recommendations were written, the research team responsible for editing the manuscript distributed the draft to all authors. Each expert was asked to comment and edit the recommendations for every ERAS item using the text editor track change system. The research team served in the role of facilitator, undertaking the synthesis between rounds. The process of synthesis included discussion among the research team, exploring all expert disagreements and comments, before synthesized recommendations were drafted for each subsequent round.

Results

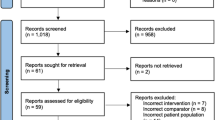

The electronic search yielded 8368 potential studies. A total of 314 articles were included in the systematic review. The selection process according to PRISMA guidelines is displayed in Fig. 1. The summary and grading of recommendations with their respective level of evidence are depicted in Table 1.

Evidence and recommendations

-

1.

Preoperative counseling

The preoperative visit is the best moment to inform patients about surgery and anesthesia. This review did not find dedicated studies on preoperative counseling for PD; however, the results of one RCT and three reviews/retrospective studies in surgery or anesthesia showed that preoperative counseling reduces fear and anxiety with a positive impact on patient recovery and hospital discharge [10,11,12,13,14]. Multimedia information seems superior to only spoken information, with or without leaflet [11].

-

Summary and recommendation: Patients should receive dedicated preoperative counseling, preferably with multimedia informational materials rather than only spoken information with or without an educational pamphlet.

-

Evidence level: Moderate

-

Grade of recommendation: Weak

-

2.

Prehabilitation

There is emerging evidence that avoiding sarcopenia and loss of visceral adipose tissue before major surgery may contribute to improved postoperative outcome. Therefore, a multimodal prehabilitation program, including physical exercise, nutritional supplements and anxiety reduction strategies, can optimize the patient’s body composition and physical performance. Prehabilitation program for colorectal surgery enhanced patient functional status, reduced postoperative morbidity and shortened hospital stay; however, evidence after PD procedure is lacking [15]. Nevertheless, in a recent RCT carried out in high-risk patients undergoing major gastrointestinal surgery, a prehabilitation program enhanced aerobic capacity and reduced postoperative complications [16]. To be effective, a prehabilitation program should be initiated at least 3–6 weeks before surgery.

-

Summary and recommendation: A prehabilitation program initiated 3–6 weeks before major surgery seems to reduce postoperative complications and preserve functional status. More data are needed to confirm its benefit in PD patients.

-

Evidence level: Moderate

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

3.

Preoperative biliary drainage

An increased number of patients with pancreatic ductal carcinoma require neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and in those particular cases, biliary drainage is a necessity and not an option. Complication related to preoperative biliary stenting has been assessed in 12 meta-analyses [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Preoperative drainage is associated with increased postoperative complications, including wound complications, but without impact on mortality [18,19,20,21, 23, 25, 26, 28]. These results are confirmed by a review of the NSQIP database, which found increased risk of sepsis and wound infections after drainage without impact on mortality [29]. One of the meta-analyses did not demonstrate any postoperative adverse effects after drainage [17]. Moreover, one single meta-analysis showed less major adverse effects with preoperative biliary drainage [24].

Two Cochrane reviews explored this topic [27]; the second review from 2012 that included four RCTs focused on percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage and two on endoscopic stenting. The risk of bias was rated as high in all trials. These studies consistently observed no difference in postoperative mortality, but morbidity rates were higher in preoperative biliary drainage. Analyzing 1500 PD, the Verona group observed neither increased major complications nor mortality after biliary drainage, but higher surgical site infection (SSI) rates [30]. Resection should be performed without prior endoscopic stenting for asymptomatic patients with bilirubin level below 250 μmol/l (15 mg/dl) [31]. We have presently no level 1 evidence for those with higher serum bilirubin levels

According to a recent meta-analysis, percutaneous biliary drainage seems to be inferior because it offers no clear advantage to the other options in terms of postoperative complications while causing significant discomfort to patients. Neither preoperative biliary drainage with plastic stent nor metallic stent was superior in terms of postoperative complications [32].

-

Summary and eecommendation: Preoperative biliary drainage increases postoperative complications without change in mortality rates. Therefore, preoperative biliary drainage should be avoided unless decompression is needed (bilirubin > 250 μmol/l, cholangitis, pruritus, neoadjuvant treatment).

-

Evidence Level: High

-

Recommendation grade for no preoperative drainage: Strong

-

4.

Preoperative smoking and alcohol consumption

Two studies including 721 and 17,564 PD patients showed that smoking was a significant predictor of primary delayed gastric emptying and grade C pancreatic fistula, respectively [33, 34].

Randomized trials reported an absolute risk reduction in complications of 20–30% when smoking was stopped 4–8 weeks preoperatively [35, 36]. However, a randomized trial of short-term (15 days) smoking cessation showed no significant differences in overall complication rates [37]. The optimal length of time of abstinence necessary to benefit previous smokers remains unclear.

Alcohol consumption was associated with increased postoperative complications like surgical site infection (SSI), pulmonary complications, prolonged length of stay (LoS) and admission to intensive care unit [38]. High alcohol consumption was associated with increased postoperative mortality, whereas low-to-moderate alcohol consumption did not appear to increase postoperative complications [38].

A univariate analysis of 539 PD showed no correlation between alcohol and pancreatic fistula [39]. A meta-analysis showed that preoperative alcohol cessation significantly decreased postoperative complications, but 30-day mortality and LoS were not affected [40].

-

Summary and recommendation: At least 4 weeks of preoperative smoking cessation is suggested to decrease wound healing complications and respiratory complications. Benefits of alcohol abstention for moderate users have not been documented.

-

Evidence level: Smoking cessation: moderate; alcohol cessation for moderate users: low; alcohol cessation for high users: high

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

5.

Preoperative nutrition

Based on pre-morbid, self-reported weight, 5% weight loss has been demonstrated to be a significant predictor of complications [41]. The majority of patients with pancreatic malignancy had significant weight loss before surgery [42]. This emphasizes the need for supplemental nutrition, trying to restore baseline nutritional status prior to complex operations. Nutritional interventions (parenteral, enteral or oral/sip feeds) are often recommended for patients with significant weight loss planned for major operations, and these interventions will usually result in weight gain [43, 44]. It remains unproven that preoperative nutritional support reduces complication rates or enhances recovery [45]. A recent evaluation of several established screening tools for malnutrition demonstrated the absence of prognostic power in pancreatic surgery [46].

Nutritional support is recommended for patients with weight loss >15% or BMI drop to <18.5 kg/m2 [47]. This may improve their sense of well-being. For patients with moderate weight loss, preoperative nutrition support is recommended by the ESPEN guidelines from 2006 to 2017, but this is based on uncontrolled or unblinded trials, or using surrogate endpoints [43, 44]. Of 35 randomized controlled trials included in latest ESPEN recommendation of 2017, none were published later than 2004 [44]. In malnourished patients requiring nutritional support before surgery, the enteral feeding through a nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding tube should be the preferred route of administration rather than total parenteral nutrition. In severe cases, surgery might be postponed to obtain adequate nutritional status at the time of surgery.

Summary and recommendations:

-

Preoperative nutritional intervention (e.g., nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding tube) is recommended for patients with severe weight loss, not as general measure (i.e., >15% weight loss or BMI < 18.5 kg/m2).

-

Level of evidence:

-

>15% weight loss: High

-

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

-

Preoperative nutritional assessment expanding beyond calculation of BMI and weight loss based on self-reported pre-morbid weight and weight scaling upon admission is not warranted.

-

Level of evidence: Moderate

-

Grade of recommendation: Weak

-

-

6.

Perioperative oral immunonutrition (IN)

Pancreatic cancer patients tend to have high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as malnutrition and cachexia [48,49,50]. Through its potential to modulate the perioperative inflammatory response, IN containing arginine, glutamine, ω-3 fatty acids and nucleotides has been associated in several meta-analyses with decreased complication rates and LoS after major gastrointestinal cancer surgery [46, 51,52,53,54,55]. However, study heterogeneity was high, and optimal timing for administration debated [56,57,58]. Specific evidence on IN in pancreatic surgery is scarce [59]. An RCT including >200 patients did not demonstrate advantage of routine postoperative IN in elective upper gastrointestinal surgery patients [57]. Three recent RCTs demonstrated a favorable effect of either pre- or perioperative enteral IN on systemic immunity in PD patients [60,61,62].

The potential benefits of different combinations of immunonutrients in major abdominal surgery were evaluated recently [63]. IN compared with control groups reduced overall and infectious complications in 83 RCTs with 7116 patients (grade of evidence low to moderate). Of note, these effects vanished after excluding trials at high risk of bias. Non-industry-funded trials did not display positive effects for overall complications, whereas industry-funded reported large effects [56,57,58].

-

Summary and recommendation: Immunonutrition is not recommended.

-

Evidence level: High

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

7.

Preoperative fasting and preoperative treatment with carbohydrates

The ESPEN guidelines recommend clear fluids to be allowed until 2 h prior to anesthesia induction and until 6 h before induction for solid foods [44]. This excludes patients with risk factors for aspiration like in gastric outlet obstruction or in diabetics with severe neuropathy. It should be emphasized that most studies excluded patients with gastroduodenal pathology.

Preoperative carbohydrates intake aims to improve metabolic conditioning to saturate liver glycogen stores immediately before surgery, thus avoiding the glycogen-depleted state caused by an overnight fasting [64]. This is achieved by a carbohydrate-rich solution taken orally the evening before and 2 h prior to surgery. The safety of carbohydrate loading is well documented. Postoperative insulin resistance is attenuated, as is thirst and anxiety [65]. These drinks are safe and cheap and improve the avoidance of dehydration, but a significant effect on postoperative complication remains to be demonstrated [66].

Summary and recommendations

-

Preoperative fasting can be limited to 6 h for solids and 2 h for liquids in patients without risk factors (i.e., gastric outlet obstruction, diabetes with neuropathy)

-

Level of evidence: Moderate

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

-

Carbohydrate loading is safe and may have some beneficial effects.

-

Level of evidence: Moderate

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

-

8.

Pre-anesthetic medication

A key strategy to reduce patient anxiety is a comprehensive preoperative communication and education program with consistent and clear messages so that patients understand the surgical pathway and engage actively in their recovery [67]. For patients undergoing procedures such as insertion of epidural catheters immediately prior to surgery, small doses of intravenous midazolam (1–2 mg) may be given to ameliorate anxiety with minimal residual effect [68].

The aim of starting a multimodal analgesic strategy prior to surgery is to reduce the need for opiates and their side effects like sedation, nausea and vomiting. Where approved, paracetamol (Acetaminophen) 1 g can be given as either tablets or soluble solution prior to surgery. NSAIDS are usually part of multimodal analgesia within ERAS pathways unless contraindicated (risk of gastrointestinal side effects, asthma or renal insufficiency). Non-selective and selective COX 2 inhibitors are available, have no effect on platelet function and reduce gastritis incidence and renal insufficiency. The use of gabapentinoids in surgical patients has shown a benefit in acute pain relief [69]. Optimal dosing has not yet been established, but a single dose between 75 and 300 mg of pregabalin preoperatively produced a 24-h reduction in opioid requirement. However, it is used with caution in elderly or in renal impairment patients, as higher doses can lead to sedation, visual disturbance or psychomotor issues affecting postoperative mobilization [70].

Summary and recommendation:

-

Pharmacological anxiolytics should be avoided as much as possible, particularly in elderly to avoid postoperative cognitive dysfunction.

-

Level of evidence: Moderate

-

Recommendation grade: Strong

-

-

Opioid sparing multimodal pre-anesthetic medication combines acetaminophen 1 g and a single dose of gabapentinoid.

-

Level of evidence: Moderate

-

Recommendation grade: Strong

-

-

NSAIDS or selective COX 2 inhibitor initiated postoperatively, if good renal function.

-

Level of evidence: Moderate

-

Recommendation grade: Strong

-

-

9.

Anti-thrombotic prophylaxis

PD is an independent risk factor for postoperative deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). It concerns a majority of elderly cancer patients at a high risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) with complications [71, 72].

The ASCO guidelines update recommended systematic postoperative thromboprophylaxis up to 4 weeks in oncologic patients undergoing major abdominal surgery with high-risk features [73]. The low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or unfragmented heparin (UFH) treatment should be started 2–12 h before surgery [72]. A recent Cochrane review reported no difference between perioperative LMWH, UFH and fondaparinux on mortality, VTE outcomes and bleeding (minor or major). LMWH is preferable because of compliance (once-daily administration) [74]. The additional use of compressive stockings and intermittent pneumatic compression devices is recommended [75].

In a comparative cohort study (n = 186), PD patients receiving thromboprophylaxis had less postoperative VTE but significantly more postoperative hemorrhages. Minor hemorrhages (no invasive treatment or transfusion) were significantly increased, while major hemorrhage (i.e., requiring concentrated red cell transfusion or hemostasis with interventional radiology or surgery) remained unchanged [76]. A large cohort study (n = 13,771) confirmed that the rate of post-pancreatectomy VTE outnumbers hemorrhages [77]. Multivariate analysis identified obesity, age >75 years and organ space infection as risk factors for late VTE.

Combined perioperative thromboprophylaxis and epidural analgesia is safe if placement or removal of catheter is delayed for at least 12 h after prophylactic LMWH. No additional hemostasis altering medications should be administered because of additive effects. LMWH should resume at least 4 h after catheter removal [78].

Summary and recommendation:

-

LMWH or UFH reduces the risk of VTE complications and should be started 2–12 h before surgery and continued until hospital discharge. Extended thromboprophylaxis (4 weeks) is advised after PD for cancer. Concomitant use of epidural analgesia necessitates close adherence to safety guidelines.

-

Evidence level: High

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

-

Mechanical measures are advised in addition to chemical thromboprophylaxis.

-

Evidence level: Low

-

Grade of recommendation: Weak

-

-

10.

Antimicrobial prophylaxis and skin preparation

The reported incidence of SSI after PD ranges between 7 and 17% [79,80,81]. It increases LoS, readmission rate and costs [82, 83]. In addition, SSI may delay postoperative treatment [84, 85].

Antimicrobial prophylaxis is recommended in PD patients to reduce infectious complications [86, 87]. The American College of Surgeons (ACS) and Surgical Infection Society recommend a single dose of intravenous cefazolin (cephalosporin of first generation) within 60 min before surgical incision [86]. An extra dose should be provided every 3–4 h during surgery to ensure adequate serum and tissue concentrations [88]. Alternative in β-lactam allergy is clindamycin/vancomycin with gentamicin.

SSI in PD patients is mainly related to bile contamination during surgery, especially in patients after preoperative biliary drainage (PBD) [89, 90]. PBD is an independent risk factor of SSI and associated with an increased bacteriobilia [91, 92]. One randomized controlled trial concluded that routine PBD increased the rate of overall complications [93]. In this context, two retrospective studies suggested the use of specific antimicrobial prophylaxis based on preoperative bile culture [91, 94]. One single RCT compared targeted antimicrobial therapy with standard regimen in hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery patients with PBD. SSI was significantly decreased in the targeted group with less organ/space SSI and less multiple drug resistant bacteria. Similar results were reported in the PD subgroup in favor of targeted prophylaxis based on bile culture [93].

Several studies reported a concordance between bacteria in intraoperative bile sample and SSI bacteria [91, 95,96,97]. Enterococcus and Enterobacter are the most frequent pathogens isolated, but Enterococcus is frequently resistant to common antibiotics (penicillins and cephalosporins) [90, 98, 99]. Two studies reported a significant reduction in SSI with piperacillin or piperacillin–tazobactam compared with standard prophylactic antibiotics [96, 99]. More recently, vancomycin and piperacillin–tazobactam were associated with less SSI in PD patients with periampullary tumors [100]. Despite these results, systematic broad spectrum antibioprophylaxis was not recommended due to the low level of evidence. Antibiotics targeted to Enterococcus species in bile contamination remain controversial in PD patients, because it is difficult to prove whether SSIs bacteria caused colonization or infection [95]. To decrease infections, three retrospective studies proposed prolonged perioperative antibiotics until microbiological culture results became available [97, 98, 101]. If bile was positive, treatment was adapted and continued until POD 5 or 10. In two studies, this was associated with reduced SSI [97, 101]. It is associated, however, with an increased risk of antimicrobial resistance, antibiotic colitis and higher costs [102]. The level of evidence remained low due to retrospective design and heterogeneity. In the recent guidelines of ACS and Surgical Infection Society, there is no evidence that antibiotics administration after skin closure decreases SSI risk.

A large multicenter cohort study reported a great variation between institutions in perioperative antibioprophylaxis, type of microorganisms in bile, wound infection cultures and antibiotics resistance [92]. The authors suggested routine intraoperative bile culture during PD to adapt antibiotherapy in postoperative infections. They also recommend reevaluating antimicrobial prophylaxis for PD based on specific microbiology data to each institution.

The use of oral antibiotic prophylaxis was investigated and is cost-effective and efficient in PD patients. Metronidazole and doxycycline have a fast complete biodisponibility [103]. Doxycycline is excreted in the liver, and bile concentration is higher than systemic. The antibiotic half-life is long enough, and second dose unnecessary, but there are no large studies in PD patients.

-

Summary and recommendation: Single-dose intravenous antibiotics should be administered less than 60 min before skin incision. Repeated intraoperative doses are necessary depending on drug half-life and surgery duration. Postoperative “prophylactic” antibiotics are not recommended but may be considered therapeutic in positive bile culture. Intraoperative bile cultures should be performed routinely in patients with endobiliary stent.

-

Evidence level: High

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

Regarding skin preparation, several RCTs have compared chlorhexidine based with iodine-based antiseptics with no significant difference in outcomes [104]. Alcohol-based preparations are recommended in first intention rather than aqueous preparations to reduce the rate of SSI [105]. There is no evidence to support the superiority of alcohol-containing chlorhexidine to iodine and alcohol skin preparation [106]. One recent RCT compared chlorhexidine gluconate to povidone–iodine in patients undergoing clean–contaminated upper gastrointestinal or hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery. There was no difference between the two groups for prevention of SSI [107].

To reduce incisional SSIs, several types of wound protectors have been developed. There is no evidence to support the use of adhesive membrane barriers over the skin. The Cochrane review including five studies reported an increased risk of SSI in the case of adhesive drapes [108]. On the other hand, several RCTs reported the efficiency of ring wound protectors to reduce the incidence of incisional SSIs in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgeries [109, 110]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis including 14 RCTs reported a significant benefit of dual-ring protector to decrease the rate of SSI in patients undergoing abdominal surgery [111]. The WHO guidelines recommend using wound protector devices in clean–contaminated abdominal surgical procedures. However, the device use should not be prioritized in low-resource settings over other interventions that prevent SSI, because of their scarce availability and associated costs [112].

-

Summary and recommendation: Alcohol-based preparations are recommended as a first option for skin preparation. Wound protectors may help to reduce the rate of SSI.

-

Evidence level: Moderate

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

11.

Epidural analgesia

Most data on epidural analgesia have to be extrapolated from historical non-ERAS pathways [113]. The analgesic effect of thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA) for a large open abdominal incision is superior to intravenous opiates according to a meta-analysis and Cochrane reviews [114,115,116]. A Cochrane review also showed that TEA reduced the incidence of gastrointestinal dysfunction after major abdominal surgery [117]. Pulmonary function is improved with TEA as compared to intravenous opiates due to reduced sedation and improved analgesia [118]. In addition to providing effective analgesia, TEA blocks a part of the neuroendocrine stress response for the duration of the block. This leads to reduced protein catabolism and improved protein synthesis provided early feeding in the immediate postoperative period [119,120,121]. In this group of patients that often have sarcopenia and poor nutritional status prior to surgery, this can have significant benefits.

The major side effects of TEA are urinary retention, motor block and hypotension. This can be reduced by using combined low-dose local anesthetics with low-dose opioids, which offers superior analgesia and avoids the need of higher local anesthetic concentrations, which are more likely to cause motor block [114, 115]. Hypotension can occur despite normal intravascular volume, so it is imperative that there is a hospital protocol to deal with the hypotension to allow the use of low-dose vasopressors to restore afterload and blood pressure. Otherwise, there is often inadvertent fluid overload due to repeated boluses of intravenous fluid. One series using TEA in pancreatic surgery showed that hemodynamic instability was common and leads to increased complications [122].

The largest prospective study on safety of central neuraxial blockade was carried out in the UK and called the NAP 3 Audit [123]. It showed that the risk of permanent injury or death from having a perioperative epidural placed was between 8 and 17 in 100,000. This risk must be weighed up against the benefits of having a TEA.

For spinal anesthesia, no specific data in pancreatic surgery are available. Spinal anesthesia using a combination of local anesthetic with an opioid such as preservative-free diamorphine or morphine can be used in addition to general anesthesia. Although the stress response is reduced only for the duration of the local anesthetic block, there is a significant downstream opioid sparing effect [124]. Patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery will benefit more than those having open surgery where other local anesthetic blocks may be needed in addition to multimodal oral analgesia.

Summary and recommendation: Mid-thoracic epidural anesthesia offers excellent postoperative analgesia and has metabolic effects to reduce the catabolic effects of surgery. A correctly placed catheter with an infusion of low-concentration local anesthetic combined with low-dose opioids improves efficacy and reduces the unwanted side effects of motor block and hypotension due to sympathetic block. TEA run for 48–72 h postoperatively appears to show maximal benefit providing that MAP is maintained and fluid excess is avoided.

-

Thoracic epidural anesthesia for open PD in the ERAS setting offers improved analgesia compared to intravenous opiates, with improving return of postoperative intestinal function and reducing pulmonary complications:

-

Level of evidence: Moderate

-

Recommendation grade: Strong

-

-

12.

Postoperative intravenous and per oral analgesia

Paracetamol/acetaminophen

Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) is effective when given regularly every 4–6 h up to 4 g per 24 h although the dose should be reduced in patients with documented liver dysfunction [125]. An alternative to the IV route is oral or rectal, and these are considerably cheaper. However, the intravenous route offers rapid onset of efficacious blood levels.

NSAIDS

Both cyclooxygenase COX 1 (diclofenac, ibuprofen) and COX 2 (parecoxib) NSAIDS can be used for their analgesic, anti-inflammatory and opioid sparing qualities. The main advantage of the selective COX 2 inhibitors is that they do not affect platelet function significantly to cause bleeding [126]. There are no studies comparing efficacy of different NSAIDS in pancreatic surgery. Due to their gastrointestinal side effects and reduction in renal blood flow, the authors are cautious in recommending their early use in an ERAS pathway for pancreatic surgery until it is clear there is no renal injury. Of note, no data are available for pancreatic surgery regarding the risk of anastomotic leakage in patients with NSAID postoperative treatment.

Intravenous opiates: morphine and hydromorphone

The use of a morphine or hydromorphone patient-controlled analgesia pump is still widely utilized in pancreatic surgery [127]. In one review of the analgesia used in 8610 patients undergoing PD, only 11% of patients received epidural analgesia, the rest receiving opioids. Thoracic epidural (TEA) was associated with lower composite postoperative complications [128].The PAKMAN trial, a large RCT, comparing IV analgesia with TEA should add valuable evidence base when completed [129].

Lidocaine infusions

Lidocaine infusions are being increasingly used intraoperatively to reduce intraoperative and postoperative opioid use. There is also an anti-inflammatory effect and improvement in postoperative return of gut function. The optimal dosing and how long to maintain the infusion has not been validated in pancreatic surgery yet [130,131,132,133].

Dexmedetomidine

Dexmedetomidine is a centrally acting alpha-2 adrenergic agonist. It has multiple effects providing intraoperative analgesia, sedation and postoperative morphine reduction. Its effect on the brain is complex, and it reduces the need for anesthesia [134,135,136]. It is used as a titrated infusion during surgery only. The main postoperative unwanted side effects are sedation and bradycardia and are dose dependent.

Ketamine

Ketamine is being used in low-dose infusions in major surgery for its analgesic effect rather than its anesthetic qualities [137, 138]. Higher dosing increases the risk of postoperative cognitive issues, particularly in the elderly.

-

Summary and recommendations: A postoperative multimodal opioid sparing strategy tailored to each institutional expertise is strongly recommended.

-

Evidence Level: Moderate

-

Recommendation grade: Strong

-

13.

Wound catheter and transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block

Continuous wound infiltration through a catheter is a reasonable alternative to epidural for open abdominal surgery. A meta-analysis on nine RCTs (n = 505) reported no difference in pain control between epidural and wound catheter in abdominal surgery [139]. A second meta-analysis including 29 RCTs (n = 2059) reported preperitoneal and subcostal catheters which lead to better pain control than subcutaneous catheters [140]. A recent RCT (n = 105) compared continuous wound infiltration to epidural for open hepato-pancreato-biliary surgeries within an enhanced recovery pathway. No significant difference was observed in the composite endpoint of pain scores, opioid side effects and patients’ satisfaction. There was a significant reduction in the use of vasopressor in the continuous wound infiltration group, with no difference in postoperative complications or length of stay [141].

Alternative local anesthesia techniques, such as transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks, are associated with opioid avoidance, and their use in laparoscopic colorectal surgery within an enhanced recovery is increasingly reported [142]. Currently, no study on the use of TAP blocks for pancreatic surgery within an enhanced recovery setting is available and no recommendation can be drawn for the use of TAP block in PD.

-

Summary and recommendation: Continuous wound infiltration through preperitoneal catheter is an alternative to epidural for open PD.

-

Evidence Level: High

-

Recommendation grade: Strong

-

14.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) prophylaxis

Adverse effects of PONV on surgical outcomes include dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, wound dehiscence and delayed discharge [143]. Type of surgery as a risk factor of PONV is debatable, but for patients with three or more other risk factors: female, non-smoking status, history of PONV or motion sickness, and postoperative opioid use, the incidence of PONV ranges from 60% to 80%, whereas 10% of patients with no risk factors will experience PONV [143,144,145].

Scant data that address PONV for patients undergoing PD exist in the literature, but studies related to colorectal, non-cardiac and laparoscopic surgery should be applicable [146]. A comparative study of patients undergoing PD with an ERAS protocol showed that early mobilization, metoclopramide and removal of nasogastric tube on day 1 or day 2 decreased the rate of PONV [147]. A prospective study of 609 patients undergoing elective surgery found that nasogastric tube placement was the most significant factor for PONV based on multiple logistic regression, suggesting that mechanical irritation may increase pharyngeal or vagal nerve stimulation [148].

Several randomized trials have evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of antiemetics in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery, which is associated with a higher incidence of PONV compared to open surgery [149]. Ramosetron compared to ondansetron was non-inferior for the treatment of PONV in moderate- to high-risk patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery in a randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial [149]. Dexamethasone combined with midazolam significantly lowered the incidence of nausea and vomiting compared with placebo after laparoscopic cholecystectomy [150]. One meta-analysis found that dexamethasone was better than ondansetron for preventing postoperative nausea in the early postoperative period (4–6 h) after laparoscopic surgery, whereas both drugs were equally effective in preventing vomiting until 24 h [151]. Another meta-analysis found that the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor antagonist combined with dexamethasone was significantly more effective than the 5-HT3 receptor alone in preventing PONV after laparoscopic surgery [152].

A prospective study reported a strong dose–response relationship between postoperative opioid use and PONV [153]. A large retrospective study found that 23% of patients with fentanyl-based intravenous patient-controlled analgesia after general anesthesia experience PONV despite single drug prophylaxis of 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor antagonist [154]. Long duration of anesthesia and the intraoperative use of desflurane were identified as independent risk factors. A recent randomized controlled crossover study showed that opioid-induced nausea and vomiting was reduced by headrest rather than eye closure, suggesting an intra-vestibular rather than a visual vestibular mismatch [155].

-

Summary and recommendation: All patients should receive PONV prophylaxis. Patients with two or more risk factors for PONV (i.e., female, non-smoking status, history of PONV or motion sickness, and postoperative opioid use) should receive a combination of two antiemetics as prophylaxis. Patients with 3–4 risk factors should receive two to three antiemetics.

-

Evidence level: Moderate

-

Recommendation grade: Strong

-

15.

Avoiding hypothermia

Episodes of hypothermia, defined as core temperature below 36 °C, may result in serious adverse postoperative complications, such as increased blood loss, cardiac arrhythmia, increased morbidity, increased mortality and wound infections [156,157,158]. Hypothermia may increase patients’ susceptibility to wound infections by causing vasoconstriction and impaired immunity [159]. Although exposure to the cold operating room environment and anesthetic-induced impairment of thermoregulatory control contribute to hypothermia, other prognostic factors include patient age, body mass index, morbidity rate and length of operation [158].

Several randomized trials and meta-analyses have shown that mild hypothermia is associated with adverse outcomes in patients undergoing abdominal and other non-cardiac operations [160,161,162,163,164,165]. A multivariate regression analysis showed that anesthesia time and volume of CO2 were independent risk factors for perioperative hypothermia in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for gastrointestinal cancer [166].

A randomized trial of patients who received forced-air convective warming for at least 30 min preoperatively showed a significant decrease in the magnitude of hypothermic exposure compared to patients who received warmed blankets on request [167]. Most studies suggest that an average pre-warming time of 30 min is sufficient to decrease intraoperative hypothermia [168]. Extending systemic warming before and after the operation may provide additional benefit. In patients undergoing major open abdominal surgery, 2 h of warming before and 2 h of warming after the procedure was associated with significantly less blood loss and complication rates compared with patients who received routine intraoperative forced-air warming [158].

Circulating-water garments may transfer more heat than forced-air warming systems, but water leakage is a concern [169]. A randomized trial of circulating-water garments compared to circulating-water garments combined with forced-air warming in major upper abdominal surgery showed that the combined method was significantly non-inferior to maintaining intraoperative core temperature [170].

-

Summary and recommendation: Clinically relevant hypothermia starts at 36 °C with regard to major adverse outcomes. Active warming (forced-air or circulating-water garment systems) should be initiated before the induction of anesthesia if the patient’s oral temperature is below 36 °C. Intraoperatively, active warming and supportive measures should continue to maintain temperature above 36 °C. Postoperatively, patients should be discharged from the post-anesthesia care unit if temperature is above 36 °C.

-

Evidence level: High

-

Recommendation grade: Strong

-

16.

Postoperative glycemic control

Several elements of enhanced recovery protocols such as preoperative carbohydrate treatment instead of overnight fasting, continuous epidural anesthesia for postoperative pain, early feeding and mobilization reduce postoperative insulin resistance and thus reduce the risk of hyperglycemia [171, 172]. Early postoperative hyperglycemia (defined as >140 mg/dL) is significantly associated with postoperative complications after PD [173]. Although high glucose variability may not be associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications, patients with high glucose variability and high glucose values early in the postoperative period are at increased risk for complications [173].

A prospective cohort study reported that high preoperative hemoglobin A1c levels were associated with significantly raised glucose levels after surgery [174]. Patients with a high HbA1c level showed almost a threefold increased risk of overall complications compared to patients with normal levels [174]. Although this association does not support a cause–effect relationship, preoperative HbA1c levels may help identify patients at higher risk of poor postoperative glycemic control after major abdominal surgery.

In an observational cohort study of patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery, early peak postoperative glucose levels higher than 250 mg/dL compared to early peak levels less than 120 mg/dL were associated with increased 30-day readmissions, whereas preoperative HbA1c levels higher than 6.5% were associated with fewer postoperative complications and a lower chance of readmission [175]. The authors hypothesized that patients with elevated preoperative HbA1c levels may be more attentively monitored with a lower threshold of hyperglycemia for insulin treatment, adding that elevated early glucose levels may be more suggestive of adverse events following surgery [175].

Perioperative hyperglycemia may increase the risk of surgical site infections in general surgery patients [176, 177]. In gastroenterological surgery, hyperglycemia was not a significant risk factor for SSI in patients with diabetes, but a blood glucose level of >150 mg/dL was associated with an increased odds of SSI in patients without diabetes [177]. A randomized study of patients undergoing hepatic and pancreatic surgery, including PD, found that perioperative intensive insulin therapy with a target blood glucose range of 4.4–6.1 mmol/L decreased rates of SSI compared to a blood glucose range of 7.7–10.0 mmol/L [178]. The intensive therapy group had a shorter length of hospitalization and a lower incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula compared to patients in the intermediate insulin therapy group [178].

The optimal blood glucose levels in the early postoperative period associated with improved clinical outcomes for surgical patients remain unclear, as is the non-inferiority of strict glucose control compared to conventional management [179]. Multicenter trials have shown that intensive insulin treatment leads to a higher incidence of hypoglycemia and increased mortality compared to moderate glucose control [180,181,182]. A randomized study in patients with pancreatogenic diabetes after pancreatic resection who received continuous monitoring of blood glucose levels with an artificial endocrine pancreas showed a significantly higher total insulin dose in the first postoperative 18 h without hypoglycemia compared with patients who had glucose levels controlled with a sliding scale method [183].

-

Summary and recommendation: Current data support an association between elevated blood glucose and adverse clinical outcomes in patients with and without diabetes. The optimal glycemic target during the perioperative period remains unclear. Glucose levels should be maintained as close to normal as possible without compromising patient safety. Perioperative treatments that reduce insulin resistance without causing hypoglycemia are recommended. Strong evidence to support the non-inferiority of strict glycemic control (blood glucose levels within normal and narrow range) compared with conventional management is lacking.

-

Evidence level: Moderate

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

17.

Nasogastric intubation

Several meta-analyses in patients with gastrectomy or abdominal surgery have shown that the selective nasogastric intubation is associated with a decreased length of hospital stay [184,185,186], an accelerated oral intake [185, 186] and an earlier recovery of bowel function [184, 185, 187]. Routine nasogastric intubation brings discomfort to the patient and is associated with increased respiratory complications in abdominal and colorectal surgery [187, 188]. Its use as a manner of decreasing anastomotic leakage is not effective in abdominal surgery [184, 185].

Most of the studies on nasogastric intubation in PD are historical series divided into pre- and post-ERAS implementation period. The improvements in length of hospital stay, incidence of DGE, accelerated bowel recovery and reintroduction of diet likely result from a myriad of changes in the perioperative care introduced by ERAS pathways [189, 190].

Historical series that evaluated the use of selective nasogastric intubation have shown no differences in insertion/reinsertion rates of the nasogastric tubes (range 4–19%), while the use of percutaneous gastrostomy to avoid nasal discomfort actually leads to both increased reoperation (23.3%) and morbidity rates [191,192,193,194,195,196]. In the largest historical series to date (n = 250), routine nasogastric intubation was associated with an increased length of hospital stay, with delays in both liquid and solid diet initiation and independently correlated with DGE [195]. Keeping with the previous guidelines, nasogastric tubes placed during the surgery should be removed before the end of the anesthesia.

-

Summary and recommendation: Maintenance of nasogastric intubation after surgery does not improve outcomes, and their routine use is not warranted

-

Level of evidence: Moderate

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

18.

Fluid balance

Numerous observational studies, including more than 1700 patients, reported an increased rate of complications associated with increased intra- and/or perioperative fluid administration after PD [197,198,199,200,201,202,203]. Excessive perioperative fluid administration causes interstitial fluid shift, and the consequent edema of the bowel wall triggers an inflammatory response with decreased anastomotic stability [203]. This could be deleterious to the pancreato-enterostomy. To date, four observational studies, gathering more than 400 patients, described an increased rate of pancreatic fistula associated with intra- and/or per-operative fluid overload [198, 204,205,206].

The role of a restrictive fluid protocol for PD was investigated in a recent meta-analysis (five RCTs and two observational studies, n = 846) that found no difference in postoperative outcomes (pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying, complications, length of stay or mortality) associated with a restrictive protocol [207,208,209,210,211]. However, each study had a different definition of restrictive protocol, and some were only applied either in the intra- or in the postoperative period, making the conclusions questionable. Another randomized trial on restrictive fluid management in 330 patients undergoing pancreatic resection found no difference in major perioperative complications between restrictive and liberal fluid management, despite neither goal-directed fluid therapy nor enhanced recovery protocol was used [211]. The latest randomized trial on fluid therapy for PD included patients within an enhanced recovery protocol and compared fluid therapy with or without a cardiac output goal-directed therapy algorithm [212]. A significant reduction in length of stay, intraoperative crystalloids and number of complications was found. The additional value of goal-directed fluid therapy when administered in conjunction with an enhanced recovery protocol is still a matter of debate, as a recent meta-analysis (23 studies, 2099 patients) found no difference in length of stay or morbidity when goal-directed fluid therapy was added within an enhanced recovery protocol for major elective abdominal surgery [213]. Of notice, this meta-analysis included mainly colorectal surgery where insensible blood loss is thought to be lower compared to pancreatic surgery. Further studies on the definition of fluid balance and on the way of achieving fluid overload are needed for pancreatic surgery within an enhanced recovery program.

-

Summary and recommendation: Avoidance of fluid overload in patients within an enhanced recovery protocol results in improved outcome. A goal-directed fluid therapy algorithm using intra- and postoperative noninvasive monitoring is associated with reduced perioperative fluid administration and potentially improved outcome.

-

Evidence level: Moderate

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

19.

Perianastomotic drainage

Three RCTs comparing placement of an intra-abdominal drain versus no-drain at the time of surgery after pancreatic cancer resection reveal controversial results. Conlon et al. [214] conducted a RCT of 179 patients reporting a higher incidence of POPF, intra-abdominal abscesses or collections within the drainage group. Accordingly, Witzigmann et al. [215] evaluated 395 patients undergoing PD showing a significant reduction in POPF occurrence and fistula-associated complications in the no-drain group. However, another RCT by Van Buren et al. [216] comprising 137 consecutive PD patients had to be aborted early due to an increase in POPF, DGE and intra-abdominal abscesses and a fourfold increase in mortality in the no-drain group. Subgroup analysis providing risk stratification according to the Fistula Risk Score (FRS) revealed that patients with a negligible/low-risk status had higher rates of clinically relevant POPF when drains were used; conversely, there were significantly fewer POPF when drains were used in moderate-/high-risk patients [217, 218].

Evaluation of early (postoperative day 3) versus late (postoperative day 5 and beyond) drain removal has been examined in an RCT [219]. Early removal of the drain in patients at low risk of POPF (amylase value in drains <5000 U/L at postoperative day 3) was associated with a significantly decreased rate of pancreatic fistula, abdominal and pulmonary complications. Therefore, a more selective, individual risk-stratified approach to intraoperative drainage placement might be justified. Several prospective and retrospective NSQUIP database analyses support that amylase activity in the abdominal drainage on postoperative day 1 has a highly predictive value for occurrence of POPF and might be beneficial for decision on early drainage removal [220,221,222]. A selective drain management protocol could be successfully implemented [223]. By a no-drain management in negligible/low-risk patients (FRS 0–2), a drain-dependent regimen for medium-/high-risk patients (FRS 3–10) with early drain removal on day 3 when low amylase levels occurred (≤5000 U/L at day 1) or later at surgeons discretion (amylase >5000 at day 1), morbidity, incidence of POPF and hospital stay could be significantly reduced [223]. We found no data to support the use of lipase rather than amylase levels for this decision making process.

Due to controversial data for non-drainage regimen in pancreatic surgery, a conservative approach with systematic postoperative drainage and early removal in patients at low risk of POPF might be recommended until data that are more distinct will be available. Finally, no data were found related to postoperative pain control from drains, which might be an issue for faster recovery.

-

Summary and recommendation: There is conflicting evidence on a no-drain approach in pancreatic surgery. Early drain removal at 72 h is advisable in patients with an amylase content in the surgical drain <5000 U/L on POD1.

-

Evidence level:

-

Selective no-drain regimen: Moderate

-

Early removal: High.

-

-

Grade of recommendation:

-

Selective no-drain regimen: Weak

-

Early removal: Strong

-

-

20.

Somatostatin analogues

Our literature search identified 13 RCTs and 12 systematic reviews on the effectiveness of somatostatin analogues to reduce pancreatic fistula complications after pancreatic surgery [224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242,243,244,245,246,247]. The latest Cochrane review on the effectiveness of somatostatin analogues was published in 2013 [247]. This systematic review included 21 trials with 2348 patients. There was no significant difference in perioperative mortality in patients who did or did not receive somatostatin analogues. The incidence of pancreatic fistula was lower in the somatostatin analogue group. Most trials did not mention the proportion of these fistulas that were clinically significant, but on inclusion of trials that clearly distinguished clinically significant fistulas, there was no significant difference between the two groups. The authors concluded that somatostatin analogues may reduce perioperative complications but do not reduce perioperative mortality. However, those results should be taken with caution due to the heterogeneity in the quality of studies included in the systematic review. Subgroup analyses for the variability in the texture and duct size of the pancreas are not available in most studies. More recently, the use of pasireotide, a somatostatin analogue that has a longer half-life than octreotide, has been assessed in a single-center, randomized, industry sponsored, double-blind trial including 300 patients (152 patients received 900 micrograms of subcutaneous pasireotide and 148 patients received a placebo twice daily beginning preoperatively on the morning of the operation and continuing for 7 days) [224]. The results of this study showed that the rate of clinically significant pancreatic fistulas (grade 3 or more), leak or abscess was significantly lower in the pasireotide group. Subgroup analysis showed similar results in patients with a non-dilated pancreatic duct.

-

Summary and recommendation: The systematic use of somatostatin analogues to reduce clinically significant POPF cannot be recommended because trial results have not been validated yet.

-

Evidence level: Moderate

-

Grade of recommendation: Weak

-

21.

Urinary drainage

If thoracic epidural analgesia is used, most patients will have trouble in voiding in the first days postoperatively, and an indwelling urinary catheter will be necessary. The choice between a transurethral or a percutaneous supra-pubic drainage will be based on patient comfort, ease of weaning and complications [248]. No trials specifically address this issue for pancreatic surgery patients [248].

-

Summary and recommendations: In patients with wound catheters or intravenous analgesia, urinary catheters can be removed on the first postoperative day or as soon as the patient is independently ambulant. All other patients should leave the operative room with an indwelling urinary catheter.

-

Level of evidence: Low

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

22.

Delayed gastric emptying (DGE)

Delayed gastric emptying after PD has an incidence of 15–35% [33, 249,250,251,252]. Since only a subset of patients will develop DGE requiring nasogastric decompression, there is no need for routine insertion of a nasogastric tube after PD. The widely used definition and classification of DGE as described by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) are based on the duration of the need for an NG tube but does not take into account the etiology [253]. Although primary DGE does occur, DGE is most commonly secondary and related to postoperative complications such as POPF and intra-abdominal infections [251, 254, 255]. Elderly and diabetic patients appear to have a greater risk to develop DGE after PD [255, 256]. Several meta-analyses assessed the relation between DGE and various surgical techniques but found no differences in DGE when looking at reconstruction of the gastro-/duodenojejunostomy in an ante-colic versus retrocolic fashion [257, 258], a pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy [259, 260] or a pylorus-preserving resection versus the classical Whipple’s procedure [261]. Minimally invasive PD does not reduce the rate of DGE compared with the open approach [262].

DGE is associated with substantially increased hospital costs and health care utilization [33, 263]. It is also worthwhile mentioning that prolonged DGE seems to be related to worse oncological outcomes [264]. In persisting DGE, better outcomes are achieved when artificial nutrition, either parenteral or enteral, is started within 10 days of operation [249]. In this context, enteral feeding beyond the gastrojejunostomy is to be preferred over parenteral nutrition [265].

-

Summary and recommendation: DGE after PD is mainly associated with postoperative complications as POPF and intra-abdominal infections. There are no acknowledged strategies to prevent DGE, although a timely diagnosis and treatment of intra-abdominal complications might reduce the duration of DGE. In patients with prolonged DGE, administration of artificial nutrition can improve outcome.

-

Evidence level: Low

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

23.

Stimulation of bowel movement

Chewing gum, according to meta-analyses of RCTs, promotes earlier recovery of bowel movements by 16 h in colorectal surgery and by 0.51 days in abdominal surgery [266, 267]. Common posology is three times a day, for 30–60 min. A RCT on its efficacy in PD showed a trend in the improvement in bowel function and no adverse events related to chewing [268]. Due to the adoption of the ERAS protocol in the middle of the trial, this study had to be terminated early (n = 51) and did not reach statistical significance [268]. Overall, chewing gum is a safe intervention and seems to improve bowel function.

Antiadhesive agents have varying effects. Polylactic film was associated with a decrease in ileus in a retrospective cohort study of 179 patients (4.1% vs. 13.3%) at the expense of complications such as skin infections and abdominal fluid collections [269]. A Cochrane meta-analysis that reviewed three RCTs on hyaluronic acid/carboxymethyl cellulose membranes shows that they prevent adhesions, but have no effect on ileus [270]. So far, no antiadhesive has been recommended as a form of prevention of postoperative ileus.

Data from meta-analyses on RCTs on the use of alvimopan, a u-receptor antagonist, show that a dose of 6–12 mg BID significantly improves bowel function in a dose-dependent manner in abdominal surgery [271,272,273] and lowers hospital costs [274]. At a dose of 6 mg, solid food tolerance was accelerated by 10 h, and bowel movements by 17 h, with a decrease of 14 h in LoS [271]. There are no specific studies with alvimopan in PD, but there is high evidence to support its use in abdominal surgery.

Moreover, two meta-analyses encompass the use of other pharmacological interventions. Bowel recovery was not significantly improved by dihydroergotamine (two trials), metoclopramide and bromopride (four trials), erythromycin (three RCTs), neostigmine (two trials) and ghrelin receptor antagonists (five trials) [273, 275]. Mosapride, a serotonergic receptor agonist, improves ileus, but so far only small trials have tested it in colorectal surgery [276, 277].

Summary and recommendation

-

Chewing gum is safe and may accelerate bowel recovery.

-

Level of evidence: Moderate

-

Recommendation grade: Weak

-

-

Alvimopan at a dose of 6–12 mg BID accelerates postoperative ileus recovery.

-

Level of evidence: Moderate

-

Recommendation grade: Weak

-

-

Mosapride appears to improve ileus.

-

Level of evidence: Very low

-

Recommendation grade: Weak

-

-

Metoclopramide and bromopride have no effect in ileus.

-

Level of evidence: Very low

-

Recommendation grade: Weak

-

-

Other drugs (ghrelin receptor antagonists, dihydroergotamine and neostigmine, erythromycin) appear to have no effect in postoperative ileus, and their routine used is not justified.

-

Level of evidence: Very low (ghrelin receptor antagonists, dihydroergotamine and neostigmine); moderate (erythromycin)

-

Recommendation grade: Weak (ghrelin receptor antagonists, dihydroergotamine and neostigmine); strong (erythromycin)

-

-

24.

Postoperative artificial nutrition

Malnutrition is preponderant among patients with pancreatic cancer, and morbidity rates of up to 40% after major pancreatic surgery including specific complications such as DGE request thorough identification and timely support of patients at nutritional risk [278,279,280]. Early normal diet according to tolerance is safe and feasible, according to several RCTs and systematic reviews [281,282,283,284], even in the presence of DGE or pancreatic fistula [279, 285]. Therefore, an early normal diet as tolerated should be encouraged. In patients in whom intake of less than 60% of their energy requirements for 7–10 days has to be expected, artificial postoperative nutritional support strategies should be considered [44, 286]. However, the route of administration is debated due to inherent morbidity of either support strategy and ambiguous results of the available literature [287,288,289]. While some studies showed a beneficial effect of early enteral tube feeding notably due to its potential to maintain gastrointestinal integrity [290,291,292,293,294], either combined parenteral nutrition or total parenteral nutrition has been suggested as alternatives when enteral nutrition was not feasible [295,296,297]. In frail patients undergoing oncological adjuvant protocols and needing long-term supplementation, feeding through tube jejunostomy may be considered [298, 299]. Considering these principles, an individual approach based on patients’ nutritional status, disease presentation and expected postoperative course should guide postoperative support strategies if normal diet at will is not sufficient.

-

Summary and recommendation: Patients should be allowed a normal diet after surgery without restrictions according to tolerance. Artificial nutrition should be considered as an individual approach according to nutritional status assessment. The enteral route should be preferred.

-

Evidence level: Early diet according to tolerance: moderate.

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong.

-

25.

Early and scheduled mobilization

It is well known that bed rest is associated with several deleterious effects such as muscle atrophy, thromboembolic disease and insulin resistance, which may delay patient’s recovery [300]. However, the available evidence on specific protocol of mobilization is scarce. A recent review compared specific mobilization protocol to control group following abdominal and thoracic surgery. A low number of studies were identified, with low quality and with conflicting results, as only a minority of the included studies reported a significant improvement in postoperative outcome associated with a specific mobilization protocol [301]. A recent randomized controlled trial for colorectal patients within an enhanced recovery protocol found that the allocation of additional specific staff, such as physiotherapists, effectively increased out-of-bed activities but without improving outcome [302]. The daily targets of mobilization following PD varied empirically in different studies from 1 to 4 h for the first postoperative day and from 2 to 6 h for the second postoperative day [189, 303, 304].

-

Summary and recommendation: Early and active mobilization should be encouraged from day 0. No evidence for specific protocol or daily targets is available for PD.

-

Evidence level: Low

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

-

26.

Minimally invasive surgery

The 2016 International Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association state-of-the-art consensus conference concluded that laparoscopic PD (LPD) is still in the investigational phase and that systematic training programs should be implemented [305]. Furthermore, the 2016 European Association for Endoscopic Surgery clinical consensus conference considered LPD feasible and safe when performed by experienced surgeons, however, only in selected cases and in high-volume centers [306]. Although a recent randomized controlled trial and a meta-analysis addressed the role of ERAS in pancreatic surgery, these studies did not differentiate for outcomes in minimally invasive pancreatic surgery [5, 307].

Recently, three randomized controlled trials compared postoperative outcome after LPD versus OPD in a total of 229 patients [308,309,310]. The first study by Palanivelu et al. [309] found a significantly shorter LoS with a median of 7 versus 13 days and significantly less intraoperative blood loss with a mean of 250 versus 400 ml in the LPD versus OPD, respectively. Duration of surgery was, however, significantly longer in the laparoscopic group. The second study was the monocenter PADULAP RCT from Spain by Poves et al. [308] in 66 patients. This study found a significantly better outcome regarding Clavien grade ≥3 complications for the LPD compared to OPD. LoS and duration of surgery were comparable in this study. Both studies were single-center studies from highly experienced centers. In both studies, sample size were calculated for length of stay as primary outcome and therefore no definitive conclusions can be drawn on the impact of LPD on postoperative complications. The third study was the multicenter LEOPARD-2 RCT from the Netherlands [310]. All patients were treated according to enhanced recovery principles. This study was stopped early after randomization of 99 patients because of safety concerns with LPD and found no difference in time to functional recovery [311].

A study from the US reviewed 865 patients who underwent minimally invasive PD (MIPD) from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample data sets (HCUP-NIS) [312]. Eighty-three percent of patients underwent the procedure in a low volume hospital (≤22 MIPD procedures per year). After adjusting for patient demographics, comorbidities and clinical diagnosis, an increase in hospital procedural volume was significantly associated with a decrease in the odds of a postoperative complication. A volume threshold was identified at 22 cases per year.

Another study from the USA reviewing 4739 patients from the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) found that patients who underwent LPD in hospitals with the lowest case volume (1–5 total PD/year) had a 3.7 times higher risk of 30-day mortality compared to the hospitals with the highest case volume (>25 total PDs/year) [313]. Only in the highest volume hospitals was LoS significantly shorter (1.3 day shorter) and readmissions lower with LPD compared to OPD [313].

Finally, a retrospective pan-European multicenter propensity score matched study reviewing 1458 patients from 14 centers in seven countries concluded that there was no difference in major morbidity, mortality and hospital stay between LPD, robot-assisted PD and OPD [314]. This study found a significantly higher POPF B/C grade in the laparoscopic group, but no increase was seen in the number of radiological drainages or reoperations.

-

Summary and recommendation: LPD should only be performed in highly experienced, high-volume centers and only within strict protocols. Safety is still a concern. Future studies should address the benefit of LPD in high-volume centers.

-

Evidence level: Moderate

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

Robot-assisted pancreatoduodenectomy (RAPD)

No studies were found assessing patients undergoing RAPD within an ERAS protocol. A systematic review and meta-analysis found only five non-randomized prospective studies comparing RAPD with open PD [315]. RAPD was associated with less blood loss and lower overall complications, but longer operative duration. No significant differences were found in the rates of pancreatic fistula, DGE and LoS compared to OPD [315].

-

Summary and recommendation: Currently, there is insufficient evidence to assess RAPD and it cannot be recommended. Prospective studies from high-volume centers are needed.

-

Evidence level: Low

-

Grade of recommendation: Weak

-

27.

Audit

In the latest Cochrane review, audit and feedback were associated with improved compliance of physician with recommended practice, as well with improved patient outcome [316]. The way feedback is provided is essential, and the likelihood of improved compliance to the desired process was obtained when a supervisor provided feedback on more than one occasion, in both written and verbal forms, with explicit targets and action plan [316]. With the development of electronic support, the use of electronic-based audit and feedback should be encouraged, as a recent meta-analysis observed an increased compliance with the desired process when electronic audit and feedback were used [317]. According to a recent expert consensus on training and implementation for ERAS, audit and data collection were among the three most important elements for a successful and sustainable implementation [318].

-

Summary and recommendation: Regular audit and feedback based on an electronic database are essential components of ERAS and are associated with improved compliance and outcome.

-

Evidence level: Moderate

-

Grade of recommendation: Strong

Conclusions

This systematic review presents the updated ERAS guidelines for PD. According to the literature search and experts consensus, the highest level of evidence was available for five items: avoiding hypothermia, use of wound catheter as an alternative to EDA, antimicrobial and thromboprophylaxis protocols and preoperative nutritional interventions for patients with severe weight loss. The results of this review confirm the value of ERAS pathways in pancreatic surgery since it reduces postoperative complications, hospital stay and costs. The use of a standard ERAS protocol as described by the present guidelines is essential in order to have a common language worldwide and to conduct multicenter studies. Therefore, a well-established and standardized ERAS protocol is paramount for evidence-based management of patients. Compliance with the new proposed protocol should be documented as part of future trials to allow benchmarking.

References

Cerantola Y, Valerio M, Persson B, Jichlinski P, Ljungqvist O, Hubner M et al (2013) Guidelines for perioperative care after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS (R)) society recommendations. Clin Nutr 32(6):879–887

Muller S, Zalunardo MP, Hubner M, Clavien PA, Demartines N, Grp ZFTS (2009) A fast-track program reduces complications and length of hospital stay after open colonic surgery. Gastroenterology 136(3):842–847

Roulin D, Donadini A, Gander S, Griesser AC, Blanc C, Hubner M et al (2013) Cost-effectiveness of the implementation of an enhanced recovery protocol for colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 100(8):1108–1114

Lassen K, Coolsen MME, Slim K, Carli F, de Aguilar-Nascimento JE, Schäfer M et al (2012) Guidelines for perioperative care for pancreaticoduodenectomy: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) society recommendations. Clin Nutr 31(6):817–830

Ji HB, Zhu WT, Wei Q, Wang XX, Wang HB, Chen QP (2018) Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery programs on pancreatic surgery: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 24(15):1666–1678

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, Grp C (2010) CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 152(11):726-W293

Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Bossuyt P, Chang S et al (2008) GRADE: assessing the quality of evidence for diagnostic recommendations. Ann Intern Med 149(12):JC6-2

Melloul E, Hubner M, Scott M, Snowden C, Prentis J, Dejong CHC et al (2016) Guidelines for perioperative care for liver surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) society recommendations. World J Surg 40(10):2425–2440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-016-3700-1

Pike I, Piedt S, Davison CM, Russell K, Macpherson AK, Pickett W (2015) Youth injury prevention in Canada: use of the Delphi method to develop recommendations. BMC Public Health 15:1274

Haines TP, Hill AM, Hill KD, McPhail S, Oliver D, Brauer S et al (2011) Patient education to prevent falls among older hospital inpatients: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 171(6):516–524

Edward GM, Naald N, Oort FJ, de Haes HC, Biervliet JD, Hollmann MW et al (2011) Information gain in patients using a multimedia website with tailored information on anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 106(3):319–324

Stergiopoulou A, Birbas K, Katostaras T, Mantas J (2007) The effect of interactive multimedia on preoperative knowledge and postoperative recovery of patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Methods Inf Med 46(4):406–409

Halaszynski TM, Juda R, Silverman DG (2004) Optimizing postoperative outcomes with efficient preoperative assessment and management. Crit Care Med 32(4 Suppl):S76–S86

Hounsome J, Lee A, Greenhalgh J, Lewis SR, Schofield-Robinson OJ, Coldwell CH et al (2017) A systematic review of information format and timing before scheduled adult surgery for peri-operative anxiety. Anaesthesia 72(10):1265–1272

Carli F, Charlebois P, Stein B, Feldman L, Zavorsky G, Kim DJ et al (2010) Randomized clinical trial of prehabilitation in colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 97(8):1187–1197

Barberan-Garcia A, Ubre M, Roca J, Lacy AM, Burgos F, Risco R et al (2018) Personalised prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded controlled trial. Ann Surg 267(1):50–56

Saleh MM, Norregaard P, Jorgensen HL, Andersen PK, Matzen P (2002) Preoperative endoscopic stent placement before pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis of the effect on morbidity and mortality. Gastrointest Endosc 56(4):529–534

Sewnath ME, Birjmohun RS, Rauws EA, Huibregtse K, Obertop H, Gouma DJ (2001) The effect of preoperative biliary drainage on postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg 192(6):726–734

Wang CC, Kao JH (2010) Preoperative drainage in pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 362(14):1343 author reply 5

Velanovich V, Kheibek T, Khan M (2009) Relationship of postoperative complications from preoperative biliary stents after pancreaticoduodenectomy. A new cohort analysis and meta-analysis of modern studies. JOP 10(1):24–29

Garcea G, Chee W, Ong SL, Maddern GJ (2010) Preoperative biliary drainage for distal obstruction: the case against revisited. Pancreas 39(2):119–126

Sun C, Yan G, Li Z, Tzeng CM (2014) A meta-analysis of the effect of preoperative biliary stenting on patients with obstructive jaundice. Medicine (Baltimore) 93(26):e189

Chen Y, Ou G, Lian G, Luo H, Huang K, Huang Y (2015) Effect of preoperative biliary drainage on complications following pancreatoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 94(29):e1199

Moole H, Bechtold M, Puli SR (2016) Efficacy of preoperative biliary drainage in malignant obstructive jaundice: a meta-analysis and systematic review. World J Surg Oncol 14(1):182

Scheufele F, Schorn S, Demir IE, Sargut M, Tieftrunk E, Calavrezos L et al (2017) Preoperative biliary stenting versus operation first in jaundiced patients due to malignant lesions in the pancreatic head: a meta-analysis of current literature. Surgery 161(4):939–950