Abstract

Background

A lower-pitched voice is one of the most common voice alterations after thyroidectomy without laryngeal nerve injury. The aim of this study was to evaluate the acoustic and stroboscopic changes and the treatment outcomes in patients with a lower-pitched voice with the goal of eventually establishing a therapeutic guideline.

Methods

Patients with a lower-pitched voice were selected according to the results of acoustic analysis among thyroidectomized patients. According to their pitch-gliding ability, patients were classified into a “gliding group” and “nongliding group,” and direct voice therapy was performed. For those who did not respond, indirect voice therapy with subsequent identical direct voice therapy was performed. Video-stroboscopy, acoustic and perceptual analysis, and subjective analysis using a questionnaire were performed before and after treatment. The results of the two groups were compared.

Results

Fifty patients were enrolled. Decreased vocal cord tension was the most common stroboscopic finding in these patients. After direct voice therapy, 87 % of patients in the gliding group showed restoration of pitch 2 months after thyroidectomy. None of the patients in the nongliding group showed improvement. After indirect voice therapy and subsequent direct voice therapy, these nonresponders finally showed improvement 4.5 months after thyroidectomy. Several characteristic stroboscopic findings of the nongliding group were identified.

Conclusions

The pitch-gliding ability and several specific stroboscopic findings were predictive of a response to direct voice therapy. Based on these findings, an individualized therapeutic approach could be applied, and the pitch of patients with a lower-pitched voice after thyroidectomy was restored earlier than expected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Voice preservation is an important concern for patients undergoing thyroid surgery. However, vocal and laryngeal symptoms are common following thyroidectomy, even without definitive recurrent or superior laryngeal nerve injury. About 87 % of patients experience voice changes immediately after thyroidectomy, even without laryngeal nerve injury [1]. In these cases, the typical voice symptoms are easy fatigue during phonation and difficulty with high-pitched and singing voices [2]. Objective measurements of vocal function after thyroidectomy show significant changes in various acoustic parameters of the voice. The most common changes are lowering of the habitual pitch, decreased vocal performance with reduced frequency and intensity range, and increased perturbation parameters such as shimmer, jitter, noise-to-harmonic ratio, and voice turbulence index [2–7]. Among them, lowering of pitch is the most common change on objective and subjective evaluations [8].

In a previous study at our institution, 18 % of patients showed a lower-pitched voice 2 weeks after thyroidectomy [9]. In many studies, progressive amelioration of the acoustic parameters was identified during the later postoperative stages, indicating that most postoperative vocal alterations in the absence of laryngeal nerve injury are temporary [1–3, 7]. However, whether patients will regain their normal preoperative vocal quality is unclear. It has been reported that among the acoustic parameters the fundamental frequency (Fo) continues at the lower level whereas the other parameters return to normal a few months after thyroidectomy [5]. Sinagra et al. [1] found that the Fo gradually recovered during the fourth and sixth postoperative months but did not reach preoperative values.

There have been many studies of voice changes after thyroidectomy without laryngeal nerve injury, but little is known about the appropriate treatment for these patients. It is reported that appropriate postoperative speech rehabilitation may achieve neuromuscular adaptation and voice improvement [10]. On this basis, we routinely apply direct voice therapy in the form of vocal function exercise (VFE) for patients who show a lower-pitched voice after thyroidectomy. The response to VFE is variable. According to our unpublished data, patients who cannot perform the vocal gliding exercise of VFE and those who show specific stroboscopic findings do not respond to VFE. For these patients, we have tried indirect voice therapy to improve the condition of the larynx prior to VFE. With this approach, these patients exhibited pitch restoration and improved voice quality. On the basis of this finding, we planned a study to establish a systematized therapeutic approach to patients with a lower-pitched voice after thyroidectomy and evaluated the effectiveness of this therapeutic approach.

The purpose of this study was to identify the acoustic and stroboscopic characteristics of patients who showed a lower-pitched voice after thyroidectomy without laryngeal nerve injury. We also evaluated the usefulness of pitch gliding as a predictor of the response to voice therapy. The eventual goal was to establish a systematized therapeutic approach for patients with a lower-pitched voice after thyroidectomy.

Materials and methods

Study design

The medical records of 589 patients who underwent total thyroidectomy at the Department of Surgery for differentiated thyroid carcinoma were evaluated retrospectively. Subjects were excluded if they had a history of having undergone head and neck surgery (including prior thyroid surgery) and if they had a >1-month history of other disorders or conditions that may have affected their voice quality at the time of the examination, such as sinusitis, allergic rhinitis, or recent upper respiratory infection. Patients who showed vocal cord paralysis before and after the surgery and those who underwent lateral lymph node dissection concurrently with thyroidectomy were also excluded. All subjects underwent video-stroboscopy, perceptual voice analysis, and computerized acoustic analysis. All were asked to complete the “thyroidectomy-related voice questionnaire” developed at our institution [11]. These evaluations were performed before the surgery and repeated 2 weeks afterward.

To collect lower-pitched-voice data, the value of a specific parameter of acoustic analysis (speaking fundamental frequency) was compared before and after the surgery in all patients. If the difference in the value was >12 Hz, the patient was considered to have a lower-pitched voice [3]. To ensure the homogeneity of the data, professional voice users and male patients were excluded. Among the selected patients, 50 completed the full follow-up and were enrolled in this study. Their ages ranged from 16–70 years (mean 53.42 ± 11.97 years).

Vocal function exercise was performed in these 50 patients for one test cycle. This therapy comprised four steps: warm-up, upward pitch gliding, downward pitch gliding, power exercise. We focused on pitch gliding because our concern was the pitch change after thyroidectomy. We classified the patients into two groups according to their pitch-gliding ability during one test cycle of VFE. If they could perform pitch gliding, the patient was categorized into the “gliding group.” If not, the patient was categorized into the “nongliding group.” The same 6-week VFE program was then applied to patients in both groups. After the cessation of VFE, identical evaluations were performed. The stroboscopic findings, acoustic analysis parameters, and questionnaire scores were compared between the two groups.

After VFE, indirect voice therapy was applied for 1 month to improve the condition of the larynx in the patients who did not show restoration of a lowered pitch. VFE was then undertaken again in these patients for 6 weeks, and the same evaluations were repeated. The results were analyzed to evaluate the usefulness of indirect voice therapy followed by VFE for the patients who did not respond to initial VFE (Fig. 1).

The institutional review board of our institution approved the design of the study.

Thyroidectomy technique

All patients were operated on by the same general surgeon using the same surgical technique and under the same conditions. During surgery, the strap musculature was retracted laterally from the midline but was not completely divided in any of the patients. Total thyroidectomy was performed by extracapsular dissection to remove both thyroid lobes and the pyramidal lobe (when present). The recurrent laryngeal nerves were identified and followed in both directions: caudally to the mediastinum and cranially to the cricothyroid junction. All vessels were ligated close to the thyroid gland. The superior thyroid artery and vein were individually ligated on the thyroid capsule to avoid injury to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. When the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve could not be readily identified, no further dissection was performed. The parathyroid glands were also identified and preserved. The cricothyroid muscle was protected from injury by electrocoagulation or manual retraction even when pyramidal lobe dissection was performed. Wound drainage with a closed-suction catheter was used at the discretion of the operating surgeon.

Video-stroboscopic examination

The whole larynx was examined using video-laryngostroboscopy (model 9200C; KayPENTAX, Lincoln Park, NJ, USA). We focused on the following findings during the video-stroboscopic examination: vocal fold edema, subglottic edema, vocal fold tension, laryngeal mucus, symmetry of the arytenoids and vocal folds, vocal fold regularity, and presence of muscle tension dysphonia (MTD).

Thyroidectomy-related voice questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed at our institution and is a self-assessment tool that measures quality of voice [11]. It consists of 20 questions. Responses to each question are scaled from a minimum of 0 (no voice alterations or symptoms) to a maximum of 80 (highest voice impairment and multiple vocal symptoms). The questionnaire was developed based on the voice handicap index and other studies on subjective symptoms related to thyroidectomy [6, 8]. The questions concern general voice complaints, representative symptoms related to laryngopharyngeal reflux and vocal cord palsy, and swallowing-related symptoms associated with thyroidectomy.

Perceptual voice analysis

Voice samples were recorded for all patients. They were instructed to read “Sanchaek” (a walk) at a comfortable volume and rate. Each patient’s voice was also evaluated perceptually during a conversation. The patients provided information on their voice history and social history. A GRBAS (grade, roughness, breathiness, asthenia, strain) score was given at the end of the evaluation session. The recorded audiotapes of “Sanchaek” were then replayed after the evaluation session to reconsider the GRBAS scores. Any variation in the GRBAS scores between reading and conversation were considered, and preference was given to the scores obtained during conversation. The voice was scored using the five GRBAS parameters: grade, the overall degree of deviance of voice; roughness, irregular fluctuation of the Fo; breathiness, turbulent noise produced by air leakage; asthenia, overall weakness of the voice; strain, impression of tenseness or excess effort. Each parameter was scored on a scale of 0–3 (0, normal; 1, slight disturbance; 2, moderate disturbance; 3, severe disturbance). Two speech therapists and one otolaryngologist judged the voices, by consensus.

Acoustic analysis

Patients were instructed to pronounce the vowel “a” at a comfortable volume and constant pitch. Each vowel pronunciation was recorded with a constant mouth-to-microphone distance of 5 cm using Computerized Speech Lab (CSL) (model 4150; KayPENTAX). All digital recordings were made in a quiet room. Each patient sustained an “a” for at least 3 s at a comfortable pitch level. The task was repeated four times or more, and the fourth trial was often the recorded sample. A multidimensional voice program (MDVP) (model 5105, version 3.1.7; KayPENTAX) was used for each analysis. The parameters considered in the analysis were Fo, perturbations of Fo (jitter), amplitude (shimmer), glottal noise (i.e., noise-to-harmonic ratio), and speaking Fo.

Voice therapy

Voice therapy was classified as direct or indirect. Direct voice therapy was performed using VFE. VFE involves a series of voice manipulations that are designed to strengthen and balance the laryngeal musculature and balance the airflow with the muscular effort. VFE comprises the following four steps, as described by Stemple et al. [12].

-

1.

Warm up—Sustain /i/ as long as possible on a comfortable note (these subjects used F above middle C).

-

2.

Stretching (upward pitch gliding)—Glide from the lowest to the highest note in the frequency range using /o/.

-

3.

Contracting (downward pitch gliding)—Glide from the highest to the lowest note in the frequency range using /o/.

-

4.

Power exercise—Sustain the musical notes middle C and D, E, F, and G above middle C for as long as possible using /o/. Repeat these notes two times.

Patients performed the exercises twice a day, with two repetitions each time, 7 days per week for 6 weeks. Each exercise session required about 15–20 min.

Indirect voice therapy comprises a vocal hygiene program that includes the following aspects: voice rest, adequate hydration, reduction/elimination of laryngeal irritants, reduction of vocal abuse and hard glottal attacks, reduction of vocal loudness and speech rate, and elimination of chronic throat clearing and coughing. These therapies are aimed at reducing vocal hyperfunction and improving the general condition of the larynx [12].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 15.0 for Windows; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Data from the two patient groups and the preoperative and postoperative values of each individual were statistically compared using Student’s t-test and a paired t-test, respectively. A p value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Acoustic and stroboscopic characteristics of a lower-pitched voice

In both acoustic and perceptual analyses, the Fo and the speaking fundamental frequency were significantly decreased postoperatively. The noise-to-harmonic ratio and grade were significantly increased after thyroidectomy. On subjective evaluation using the questionnaire, the score increased significantly from an average of 4.64 preoperatively to 33.3 postoperatively (Table 1). These results indicate that all patients with a lower-pitched voice after thyroidectomy showed a definitively lowered pitch and decreased quality of voice both objectively and subjectively.

With regard to stroboscopic findings, decreased vocal cord tension was the most common change after thyroidectomy followed by decreased regularity, symmetry, amplitude, and mobility and increased vocal cord edema. These changes were observed in about half of the patients (Fig. 2). Glottic gap, subglottic edema, mucus in the larynx, and change in vocal cord color were observed in a minority of patients (Fig. 3).

Response to VFE

According to the pitch-gliding ability in one VFE test cycle, 23 patients were classified into the gliding group and 27 into the nongliding group. The mean age of the patients in the gliding group was 54.12 ± 10.12 years, and that of the patients in the nongliding group was 52.27 ± 11.25 years. The mean ages were not significantly different. None of the acoustic or perceptual parameters were significantly different between the two groups (Table 2).

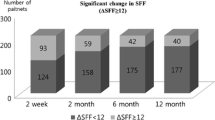

The same 6-week VFE program was applied to the patients in both groups. The results of the acoustic and perceptual analyses and the questionnaire score before and after VFE in the two groups were compared (Table 2). In the nongliding group, no parameters showed a significant difference after VFE. In contrast, in the gliding group, the Fo and speech fundamental frequency (SFF) were significantly increased after VFE, and breathiness and the questionnaire score were significantly decreased. These results indicate that patients in the gliding group showed definite recovery of their voice tone, less breathiness, and subjective improvement of their voice. Of the 23 patients in the gliding group, 20 (87 %) showed reversal of the lowered pitch and improved voice quality. Another three patients (13 %) failed to show reversal of pitch after VFE. None of the 27 patients in the nongliding group showed restoration of their normal pitch. The 30 patients who did not respond to VFE (three patients in the gliding group and all 27 patients in the nongliding group) underwent the next step of our therapeutic approach (Fig. 1).

The differences in stroboscopic findings between the two groups were also evaluated (Fig. 4). In terms of vocal cord tension, 63 % of the patients in the nongliding group showed a severe decrease, but the majority of patients in the gliding group showed normal or mildly decreased tension. Similar results were observed with regard to the other above-mentioned stroboscopic findings. Patients in the nongliding group showed a higher percentage of severe vocal cord edema, presence of subglottic edema and mucus in the larynx, MTD, and decreased vocal cord regularity and symmetry than patients in the gliding group.

Treatment outcome of the gliding group

All 23 patients in the gliding group showed reversal of their lower-pitched voice after the 6-week VFE period. Because we evaluated them 2 weeks after thyroidectomy, these patients had a restored pitch 2 months after the surgery (postoperative 2 weeks + VFE for 6 weeks). The three patients who did not respond to VFE underwent indirect voice therapy for 1 month and subsequent second course of VFE for 6 weeks. Afterward, these three patients finally showed reversal of their lowered pitch and displayed improved voice quality. Consequently, these three patients had a restored normal pitch 4.5 months after thyroidectomy (postoperative 2 weeks + initial VFE for 6 weeks + indirect voice therapy for 4 weeks + second VFE for 6 weeks).

Treatment outcome of the nongliding group

None of the 27 patients in the nongliding group responded to the initial VFE. Therefore, these patients underwent indirect voice therapy for 1 month and subsequently another course of VFE for 6 weeks. After this treatment, identical evaluations were performed. The final treatment outcomes of these patients are summarized in Table 3. Fundamental frequency and speaking fundamental frequency were significantly increased after indirect voice therapy and subsequent VFE. In addition, roughness, breathiness, and the questionnaire score were significantly decreased after the final therapy. Although there was no statistical significance, the other parameters also improved. These results indicate that indirect voice therapy with subsequent VFE was effective in these patients. In other words, applying indirect voice therapy prior to subsequent VFE was more effective in patients in the nongliding group. The stroboscopic changes of these patients are shown in Table 4, and comparisons of the findings before and after VFE and before and after indirect voice therapy with VFE are shown in Fig. 5. The changes in stroboscopic findings before and after initial VFE were not as noteworthy (Fig. 5a). However, the changes before and after indirect voice therapy with VFE were dramatic (Fig. 5b). In terms of the decreased vocal cord tension, for instance, 50 % of the patients showed a moderate decrease and only 15 % of the patients showed normal tension. However, after indirect therapy with subsequent VFE, only 10 % of the patients showed a moderate decrease, and most of the patients showed normal tension or mildly decreased tension (39 % normal tension, 51 % mildly decreased tension). Other findings showed similar trends. In summary, the stroboscopic findings were not notably improved after initial VFE but showed great improvement after indirect voice therapy with subsequent VFE.

Discussion

Temporary or permanent postoperative vocal changes can have a serious impact on a patient’s quality of life, particularly that of professional voice users. A review of the literature showed that 37–87 % of patients who undergo thyroid surgery experience vocal changes or vocal complaints during the early postoperative period [1, 3–5, 7]. Objective measurements of vocal function after thyroid surgery show significant changes in various acoustic parameters of the voice. The most important changes are lowering of the habitual pitch, decreased vocal performance with reduced frequency and intensity range, and an increase in perturbation parameters such as shimmer, jitter, noise-to-harmonic ratio, and voice turbulence index. Among these changes, lowering of the habitual pitch is the most frequently observed change and is the most common complaint of thyroidectomized patients [1–3, 5–7].

Sinagra et al. [1] reported that the most common alterations after thyroidectomy were voice alteration while speaking loudly, changes in voice pitch, and voice disorders while singing. They reported that Fo measurement showed an initial decrease postoperatively and progressive recovery by the sixth month but did not reach preoperative values. They assumed that this might be attributed to a decrease in cordal tension by alterations in the functional character of the cricothyroid muscle or superior laryngeal nerve. In our study, patients with a lower-pitched voice after thyroidectomy had decreased vocal cord tension as the most frequently observed finding (86 %), followed by decreased vocal cord regularity, symmetry, amplitude, and mobility. These changes in stroboscopic findings can be attributed to changes in acoustic parameters such as an increased noise-to-harmonic ratio and grade—meaning an objective decrease in voice quality. Patients also subjectively reported the change in their voice by means of significantly increased questionnaire scores.

As already noted, much is known about the diagnosis of voice changes after thyroidectomy. However, the most appropriate treatment of a lower-pitched voice after thyroidectomy is not yet established, and there are no guidelines for treating these patients. Generally, voice therapy is applied to patients who exhibit voice disturbances after thyroidectomy, although successful treatment of such patients is considered difficult [13]. We utilized VFE as the first treatment regimen for patients with a lower-pitched voice after thyroidectomy. In the clinical setting, VFE is one of several means of improving the voices of patients seeking treatment for a voice disorder. VFE, which is considered a physiologic approach, was selected because it addresses many aspects of voice production, including laryngeal tension, breath support, voice onset, and resonance attributes that may be affected in voice disorders. These exercises, as described by Stemple et al. [12], reportedly strengthen and rebalance the subsystems involved in voice production (i.e., respiration, phonation, resonance) through a program of systematic exercise. Those authors speculated that the exercises help rehabilitate the voice by improving the strength, endurance, and coordination of the systems involved in voice production. Although the assumptions underlying the physiologic basis of the exercises have not been validated empirically, the exercises have proven useful for improving and enhancing selected aspects of vocal performance of speakers with healthy voices [12], singers [14], teachers with voice disorders [15], and elderly individuals [16]. Furthermore, the frequency range was improved. In Stemple et al.’s [12] research, VFE extended the low end of the frequency range by an average of 15 Hz and the high end by an average of 123 Hz.

We focused on the effect of VTE on pitch improvement. With the VFE approach, four specific exercises are practiced, including maximum vowel prolongations and pitch glides using specific pitch and phonetic contexts. Because the goal of voice therapy for patients with a lower-pitched voice is restoration of pitch, we focused on pitch gliding during VFE and stressed the importance of this exercise to the patients with the assumption that pitch gliding exercises would restore the patients’ normal pitch. We also postulated that if the patient could not perform pitch gliding after thyroidectomy, he or she could not perform VFE successfully. Thus, the objective parameters of acoustic analysis would not be improved after VFE.

Altogether, 23 of 50 patients were able to perform pitch gliding initially and were categorized as the gliding group. Their acoustic parameters after VFE indicated objective restoration of pitch. The Fo changed from 175 to 187 after VFE (p = 0.003), and the speaking fundamental frequency changed from 157 to 172 after VFE (p = 0.002). These patients also reported subjective improvement of their voice after VFE (questionnaire score changed from 39.77 to 29.76, p = 0.007). Thus, VFE was effective in restoring the lower-pitched voice after thyroidectomy in patients able to perform pitch gliding.

The other 27 patients were unable to perform pitch gliding initially and were categorized as the nongliding group. Their pitch and voice quality were not significantly improved after VFE either objectively or subjectively. Of the 23 patients in the gliding group, 20 showed improvement after VFE. None of the 27 patients in the nongliding group showed improvement after VFE. Therefore, pitch gliding is a sensitive indicator of responsiveness to VFE, as we postulated, with 87 % sensitivity and 100 % specificity. That is, patients who performed pitch gliding successfully after thyroidectomy showed definite restoration of their normal pitch after 6 weeks of VFE. However, patients who were unable to perform pitch gliding did not show restoration of pitch or improvement of voice quality after VFE.

A systematized therapeutic approach can be established on the basis of these findings. If the patient can perform pitch gliding after thyroidectomy, VFE can be applied with a therapeutic intention. If the patient cannot perform pitch gliding, instead of applying VFE directly another therapeutic approach should be considered. For these patients, we applied indirect voice therapy.

Indirect voice therapy is a vocal hygiene program that aims to reduce vocal hyperfunction (muscle tension) and improve the general condition of the larynx. Many studies have reported the effectiveness of indirect voice therapy in various diseases and conditions of the larynx or vocal cords. In the presence of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease, indirect voice therapy is also reported to have a synergistic effect with traditional medical therapy in improving not only the disease status but also voice quality by improving the general condition of the larynx [17–19]. Our previous study indicated that indirect voice therapy has a synergistic effect with medical therapy in laryngopharyngeal reflux disease because it prevents vocal abuse and affords vocal rest, which is thought to accelerate the decreases in erythema and subglottic and vocal cord edema [20].

We applied this technique to patients in the nongliding group who did not respond to the initial VFE under the assumption that the laryngeal conditions of these patients might be poorer than the others. In other words, the response to VFE would be enhanced after improving the worsened laryngeal condition and removing muscle tension with indirect voice therapy. The results were as we expected. The acoustic parameters that initially did not show improvement with immediate VFE showed dramatic improvement after indirect voice therapy and subsequent VFE. The changes in the stroboscopic findings of these patients were in agreement. After initial VFE, the stroboscopic parameters were unremarkable. However, changes in these parameters after indirect voice therapy with subsequent VFE were noteworthy. These results indicate that indirect voice therapy was effective in improving the laryngeal condition and could be attributed to restoration of the normal pitch and improved voice quality.

We postulated that the laryngeal condition of the patients in the nongliding group would be poorer than that of those in the gliding group. We thus compared the stroboscopic findings of the two groups. Patients in the nongliding group showed a high incidence of specific stroboscopic findings such as a severe decrease in vocal cord tension, severe vocal cord edema, presence of subglottic edema and mucus in the larynx, MTD, and decreased regularity and symmetry. These findings may be a result of laryngeal mucosal changes due to modifications of the vascular supply and/or venous drainage of the larynx [4], and they may reflect a poor laryngeal condition. Therefore, such stroboscopic findings can be predictive of a poor response to direct VFE as can the pitch-gliding ability.

Based on these finding, we formulated an effective therapeutic approach to patients with a lower-pitched voice after thyroidectomy. Patients who can perform pitch gliding after thyroidectomy and who do not show specific stroboscopic findings (severe decrease in vocal cord tension, severe vocal cord edema, presence of subglottic edema, mucus in the larynx, MTD, or decreased vocal cord regularity and symmetry) are expected to have improved pitch and voice after 6 weeks of VFE. However, patients who cannot perform pitch gliding and who show specific stroboscopic findings should undergo indirect voice therapy in advance of VFE (Fig. 6).

We achieved good results using this structured therapeutic approach. Patients in the gliding group recovered their pitch after 6 weeks of treatment (overall, 2 months after thyroidectomy: postoperative 2 weeks + VFE 6 weeks), and patients in the nongliding group recovered their pitch 4.5 months after thyroidectomy (postoperative 2 weeks + VFE 6 weeks + indirect voice therapy 4 weeks + VFE 6 weeks). If we apply this therapeutic approach prospectively, patients in the nongliding group can recover their pitch after 3 months of treatment (postoperative 2 weeks + indirect voice therapy 4 weeks + VFE 6 weeks). This is notably faster than the spontaneous recovery period reported elsewhere (6 months after thyroidectomy) [1].

Conclusions

Using the proposed treatment guidelines, the outcome of patients with a lower-pitched voice after thyroidectomy can be improved, and the most common complaint of thyroidectomized patients (i.e., a lower-pitched voice) can be overcome. Based on these results, we are planning a prospective study to demonstrate conclusively the effectiveness of this treatment strategy.

References

Sinagra DL, Montesinos MR, Tacchi VA et al (2004) Voice changes after thyroidectomy without recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. J Am Coll Surg 199:556–560

Hong KH, Kim YK (1997) Phonatory characteristics of patients undergoing thyroidectomy without laryngeal nerve injury. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 117:399–404

Debruyne F, Ostyn F, Delaere P et al (1997) Acoustic analysis of the speaking voice after thyroidectomy. J Voice 11:479–482

Stojadinovic A, Shaha AR, Orlikoff RF et al (2002) Prospective functional voice assessment in patients undergoing thyroid surgery. Ann Surg 236:823–832

Soylu L, Ozbas S, Uslu HY et al (2007) The evaluation of the causes of subjective voice disturbances after thyroid surgery. Am J Surg 194:317–322

De Pedro Netto I, Fae A, Vartanian JG et al (2006) Voice and vocal self-assessment after thyroidectomy. Head Neck 28:1106–1114

Musholt TJ, Musholt PB, Garm J et al (2006) Changes of the speaking and singing voice after thyroid or parathyroid surgery. Surgery 140:978–988

Van Lierde K, D’Haeseleer E, Wuyts FL et al (2010) Impact of thyroidectomy without laryngeal nerve injury on vocal quality characteristics: an objective multiparameter approach. Laryngoscope 120:338–345

Chun BJ, Bae JS, Chae BJ et al (2012) Early postoperative vocal function evaluation after thyroidectomy using thyroidectomy related voice questionnaire. World J Surg 36:2503–2508. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1667-0

Aluffi P, Policarpo M, Cherovac C et al (2001) Post-thyroidectomy superior laryngeal nerve injury. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 258:451–454

Nam IC, Bae JS, Shim MR et al (2012) The importance of preoperative laryngeal examination before thyroidectomy and the usefulness of a voice questionnaire in screening. World J Surg 36:303–309. doi:10.1007/s00268-011-1347-5

Stemple JC, Lee L, D’Amico B et al (1994) Efficacy of vocal function exercises as a method of improving voice production. J Voice 8:271–278

Dursun G, Sataloff RT, Spiegel JR et al (1996) Superior laryngeal nerve paresis and paralysis. J Voice 10:206–211

Sabol JW, Lee L, Stemple JC (1995) The value of vocal function exercises in the practice regimen of singers. J Voice 9:27–36

Roy N, Gray SD, Simon M et al (2001) An evaluation of the effects of two treatment approaches for teachers with voice disorders: a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Speech Lang Hear Res 44:286–296

Gorman S, Weinrich B, Lee L et al (2008) Aerodynamic changes as a result of vocal function exercises in elderly men. Laryngoscope 118:1900–1903

Vashani K, Murugesh M, Hattiangadi G et al (2010) Effectiveness of voice therapy in reflux-related voice disorders. Dis Esophagus 23:27–32

Selby JC, Gilbert HR, Lerman JW (2003) Perceptual and acoustic evaluation of individuals with laryngopharyngeal reflux pre- and post-treatment. J Voice 17:557–570

Hanson DG, Jiang JJ, Chen J, Pauloski BR (1997) Acoustic measurement of change in voice quality with treatment for chronic posterior laryngitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol l06(4):279–285

Park JO, Shim MR, Hwang YS et al (2012) Combination of voice therapy and antireflux therapy rapidly recovers voice-related symptoms in laryngopharyngeal reflux patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 146:92–97

Conflict of interest

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nam, IC., Bae, JS., Chae, BJ. et al. Therapeutic Approach to Patients With a Lower-Pitched Voice After Thyroidectomy. World J Surg 37, 1940–1950 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2062-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2062-1