Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

The prevalence of pelvic floor disorders (PFD) and their impact on quality of life of women vary among different populations. The purpose of this study was to assess the prevalence of symptoms of PFD, and their degree of bother in a convenience sample of Lebanese women, and to evaluate health-care seeking (HCS) behavior related to PFD.

Methods

Women visiting clinics in a University Medical Center in Beirut, Lebanon, completed the self-filled validated Arabic version of the Global Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire (PFBQ). Data covering demographics, comorbidities, and HCS behavior related to PFD were collected. Total individual PFBQ scores, individual PFD symptom scores and HCS behavior were correlated to demographic data and comorbidities.

Results

The study participants included 900 women. PFBQ scores were significantly higher in women of older age, women with a lower level of education, women with higher vaginal parity, and women who engaged in heavy lifting/physical activity. BMI >25 kg/m2 was the strongest independent risk factor for the presence of PFD symptoms. The overall prevalence of urinary incontinence was 42 %. Anal incontinence was the most bothersome PFD. Almost two thirds of the women reported HCS due to any aspect of PFD. Among symptomatic women who believed that their PFD warranted HCS, financial concern was the most common obstacle irrespective of age and educational level.

Conclusions

In this convenience sample of Lebanese women, PFD symptoms were common and were significantly correlated with demographic characteristics and self-reported comorbidities. The key reason for not seeking health care related to PFD was financial concern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pelvic floor disorders (PFD) affect at least one quarter of women and continue to cause significant morbidity over time [1]. While most studies are based on treatment-seeking populations, the true prevalence of PFD is best obtained by screening women in the general population [2]. The prevalence of PFD varies across geographic areas and in relation to socioeconomic factors. The EPIC study, in which about 19,000 individuals were surveyed in Canada, Germany, Italy, Sweden and the UK, revealed country-specific variability in the prevalence of urinary symptoms and overactive bladder (OAB) [3]. The epidemiology of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is even more heterogeneous across different populations [1, 4–6], and its prevalence depends on factors such as ethnicity, family history, medical morbidities, body mass index (BMI), and behavioral factors, among others [7]. In addition, it is now established that parity and obstetric events are important risk factors in the development of PFD [7].

Studying the prevalence of PFD and their impact on women’s quality of life (QoL), as well as understanding women’s health-care seeking (HCS) behavior in specific populations are necessary prerequisites for shaping public health policies and prioritizing resource allocation. The incidence, prevalence, and impact of specific PFD on QoL have been studied using a variety of questionnaires [8]. The global Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire (PFBQ) is a short nine-item self-administered questionnaire that has been validated as a tool to evaluate symptoms in nine domains: stress urinary incontinence (SUI), urinary urgency, urinary frequency and nocturia, urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), voiding difficulty, POP, obstructed defecation, anal incontinence (AI), and dyspareunia [9]. The term “global” preceding PFBQ refers to assessing the symptom severity based on a Likert scale bother score, rather than its impact on specific functions and activities of life.

Lebanon is a country located at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian hinterland with an estimated population of 4.82 million [10]. The Lebanese population is peculiar in having a “pan-ethnic” background due to the fact that, throughout history, different peoples have occupied or settled in this geographic area of the world. The well-recognized religious and denominational diversity of the Lebanese population renders the study of PFD, which have culture-specific psychosocial consequences, of particular value. Since the official and spoken language in Lebanon is Arabic, an Arabic version of the PFBQ was developed and found to be reliable and valid in a group of Lebanese women attending outpatient clinics at a University Medical Center in Beirut, Lebanon [11].

The purpose of this study was to explore the prevalence of various PFD symptoms and the degree of bother of these symptoms, and to assess HCS behavior in a convenience sample of Lebanese women.

Materials and methods

Population sample

After receiving ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board, data were collected between November 2014 and February 2015. The study population comprised a convenience sample of women approached by a trained research assistant in the waiting areas of clinics in a large University Medical Center in Beirut, Lebanon. All primary care and specialty clinics were included, with the exception of obstetrics and gynecology, urology, and ophthalmology clinics. The exclusion of participants in waiting areas for ophthalmology clinics was for obvious reasons, as the survey requires written responses. By excluding obstetrics and gynecology, and urology clinics, sampling bias was minimized, especially with regard to calculating the proportion of symptomatic women who were actively seeking health care related to PFD. Pregnant women were also excluded. After reviewing the oral consent form including study details, women who consented to participation completed a self-filled anonymous questionnaire in a private setting.

Questionnaire and measures

The survey included the validated Arabic version of the global PFBQ (Appendix 1), in addition to questions on demographics, comorbidities, and HCS behavior related to PFD (Appendix 2).

The PFBQ is a nine-item questionnaire that includes symptoms and bother related to PFD. The participant is first asked about the presence/absence of each symptom, and when a positive response is provided (symptom is present), she is asked to estimate the bother level using a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘a lot’. Together, the screening and bother questions are used to generate a new variable for each symptom, as follows; 0 no symptom; 1 symptom present with no bother; 2 symptom present with little bother; 3 symptom present with some bother; 4 symptom present with moderate bother, and 5 symptom present with a lot of bother. Similar weights are given to all symptoms. Summation of individual scores of the nine symptoms results in a total score ranging from 0 to 45. In order to obtain a range from 0 to100, scores of each item are multiplied by 20 (i.e. 0 – 5 × 20). The average PFBQ score is then obtained by adding individual scores for the nine domains and dividing by 9.

Several questions were either recoded or used to generate new variables when necessary. For example, a new variable was computed to describe urinary incontinence (UI), as follows: UI ‘no’ if the respondent answered negatively to both SUI (Q1) and UUI (Q4); UI ‘yes’ if the respondent answered positively to either of the two questions. Those with UI were further categorized, as follows: SUI ‘yes’ if answered positively to Q1 and negatively to Q4; UUI ‘yes’ if answered negatively to Q1 and positively to Q4; and mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) ‘yes’ if answered positively to both. Participants were arbitrarily divided into three age groups (younger than 40 years, between 40 and 59 years, and older than 60 years), similar to the distribution adopted in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) [12].

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata (SE version 12). An exploratory data analysis was first conducted to examine the frequencies and percent distributions of categorical variables, and the central tendency estimates (e.g., means and medians) and spread of continuous measures. Boxplot and bar chart graphs were used to illustrate the distribution of specific variables. Additional statistical analyses were conducted to examine associations between variables of interest, including Pearson’s chi-squared test for two categorical variables, and binary logistic regression for binary outcomes and several independent variables. Nonparametric tests were used as appropriate for continuous nonnormally distributed outcomes (Rank-sum test and Kruskal-Wallis test). Therefore we provide means and standard deviations for continuous nonnormally distributed variables in the tables, and used nonparametric tests (Kruskal-Wallis test and rank sum test) to compare the ranks/median scores across categorical variables, and to test for statistical significance of the various associations. P values <0.05 were taken as indicating statistical significance.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the participants

A total of 1,220 women were approached and the final sample comprised 900 women (73.7 %). Of these women, 620 (68.9 %) were attending well-care/family medicine clinics, 208 (23.1 %) surgical clinics, 40 (4.4 %) internal medicine and its subspecialty clinics, and 32 (3.5 %) dermatology clinics. Demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. About 40 % were less than 40 years of age, and 40 % were between 40 and 59 years of age. About 70 % had completed a university education. The prevalence of smoking among the participants was 35.2 %, and their average BMI was 25.2 ± 3.9 kg/m2. Among the women who reported ever giving birth, 21.8 % had had at least one cesarean delivery (CD), and among all the women, 15.4 % had had a prior hysterectomy and 13.8 % had had a prior pelvic floor/incontinence surgical procedure.

PFBQ: total score, PFD symptom prevalence, and variations in relation to demographics and comorbidities

As shown in Table 2, the total PFBQ score was significantly higher in women of older age, women with a lower level of education, women with higher vaginal parity, and women who engaged in heavy lifting/physical activity. . The total PFBQ score was also significantly higher in women with diabetes and those with hypertension compared with those without. A history of hysterectomy or prior pelvic floor surgery was also significantly associated with higher PFBQ scores. Chronic cough was not significantly associated with total PFBQ scores, nor was the number of CDs.

The PFBQ exhibited good internal consistency in our sample (Cronbach alpha 0.88). Of the 900 women, 93 (10 %) had at least one missing response to the nine-item symptom questionnaire and thus were excluded from the PFBQ total score. The 807 women with complete data were compared with the 93 women with missing data across various demographic and other variables in order to evaluate the extent of information bias introduced by excluding the 93 women from the PFBQ total score. The only significant difference between the two groups was age: a higher percentage of women aged 40 – 59 years (15.6 %) had missing PFBQ responses compared to women older than 60 years (7.5 %) or younger than 40 years (5.4 %, P < 0.001).

As shown in Table 3, 20 – 43 % of participants reported symptoms in at least one of the nine domains, and 1 – 5 % reported maximum bother (bothered a lot) in at least one domain. A total of 308 women (35 %) reported no symptoms at all, 72 (8 %) had only one symptom present, 62 (7 %) had two symptoms, and 55 (6 %) reported all nine symptoms. Across the nine domains, of all symptoms dyspareunia had the highest prevalence (43.2 %) followed by AI (39.8 %). When combining moderate and severe bother of any single symptom, AI was found to be the most bothersome (14.0 %). Symptoms related to POP had the lowest prevalence (20 %).

Among the participants, 58.0 % reported no UI. The prevalence of UI and UI subtypes varied with age (P < 0.001; Fig. 1). While 86.3 % of women younger than 40 years reported no incontinence, only 16.3 % of women aged 60 years or older reported no incontinence. SUI was the most prevalent type of UI in all women younger than 60 years, while MUI was the most prevalent type in women aged 60 years or older.

In multiple binary logistic regression, BMI >25 kg/m2, diabetes and hypertension were consistent risk factors for each one of the nine symptoms, except dyspareunia in the case of diabetes and hypertension; chronic cough and smoking were not significant risk factors (Table 4). However, when controlling for age, education and vaginal parity, most of the associations were attenuated, and statistical significance was lost except for the associations between hypertension and urinary urgency, between hypertension and dyspareunia, and between BMI >25 kg/m2 and UUI, obstructed defecation, AI and dyspareunia (Table 4). Smoking, when controlling for age, education and vaginal parity, was only associated with AI (Table 4).

Treatment-seeking patterns

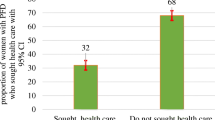

Of the 900 women who participated, 118 declined to respond to the question on HCS behavior. Of those who replied, 65.6 % reported HCS for PFD. The mean PFBQ score of those who reported HCS behavior was higher than that of non-seekers (P = 0.001; Table 2). All symptoms of PFD, except UUI and POP, were independently associated with HCS behavior (Table 5). HCS for PFD was more prevalent among the older age groups. Interestingly, HCS behavior was not related to educational level as it ranged from 61.9 % among those with primary school education to 66.2 % among those with a university degree (P = 0.882).

With regard to reasons for not seeking health-care for PFD in relation to age group, the reason most commonly reported by women younger than 40 years was “disease not severe enough” (35.7 %), while the reason most commonly reported by women aged 60 years or older was “expensive medical expenses” (45.7 %; Fig. 2a). It is worth noting that women were able to report multiple reasons for not seeking care. When excluding “disease not severe enough” in all age groups, 68.7 % of women older than 40 years reported the unaffordability of health-care as the most common obstacle to seeking care, while “a personal and sensitive problem” was the most commonly reported reason (31.5 %) in women younger than 40 years (computations based on values shown in Fig. 2a). The distribution of the five different reasons was not significantly different when comparing women of various educational levels (Fig. 2b). Here too, when the answer “my disease is not severe enough” was excluded, unaffordability of PFD-related health-care was the most commonly reported reason for not seeking care among all women, irrespective of their educational level (Fig. 2b).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study that was not based in the community, the overall prevalence of UI was 42 %, while AI was the most bothersome PFD. Almost two thirds reported HCS due to any aspect of PFD. The validity of the PFBQ as a tool for identifying and assessing the degree of bother of common PFD has already been established [9], and the Arabic version of the PFBQ has been validated in a population identical to the one targeted in this study [11]. Consequently, the absence of a physical examination and further evaluation should not have affected the validity of our results. The Arabic version of PFBQ was therefore a convenient tool to study the prevalence pf PFD in our population because of its clarity, the relatively short time for self-filling, and the simple global Likert scale bother score. Lebanon is the most religiously diverse country in the Middle East, and arguably in the world. Along with religious diversity, socioeconomic and subcultural heterogeneity render the adoption of a “global” Likert scale bother score (such as the one used in PFBQ) preferable to the evaluation of the impact of PFD on specific aspects of life functions and activities.

The overall 42 % prevalence of UI is consistent with the findings of other studies, including the NHANES in the USA [12], a survey conducted in rural East Turkey [13], and a cross-sectional study in women attending primary care clinics in Saudi Arabia [14]. However, it was higher than the 30 % prevalence found among 2,180 Saudi women with a mean age of 30 ± 10 years [15]. This illustrates the importance of age in cross-sectional prevalence studies, especially because the incidence of PFD changes with age. The prevalence of UI was notably different in our population in which the prevalence of pure UUI was lower across all age categories than found in most studies. Since “urinary urgency” is the necessary and sufficient symptom for the definition of OAB [16], we can assume that the prevalence of OAB with at least “a little bother” was about 35 % in our population. This finding is consistent with the results of the EpiLUTS internet-based survey conducted in the USA, the UK and Sweden, in which 29.1 % of female respondents older than 40 years were at least “somewhat bothered” by their OAB symptoms [17].

About 18 % of our study population were at least “a little bothered” by the presence of a vaginal bulge. In the initial PFBQ study, this symptom was found to have good correlation with the stage of prolapse [9]. In a review of 30 studies evaluating a total of 83,000 women in 15 developing countries, the mean prevalence of POP was 19.7 % (range 3.4 – 56.4 %) [5]. In a community-based study in which 504 married women residing in a Lebanese village underwent a pelvic examination, clinically significant POP (defined as a leading edge within 1 cm of the hymen) was found in 3.6 % of nulliparous, 6.5 % of primiparous, 22.7 % of secondiparous, 32.9 % of triparous, and 46.8 % of tetraparous women [18]. It is unknown whether the difference in the prevalence of POP across the world may be partially attributed to the effect of POP corrective surgery which is presumably more frequent in the developed world.

The 39.8 % prevalence of AI in our study population is higher than frequently reported elsewhere [1, 9]. A possible explanation is that our questionnaire captured not only stool incontinence but also flatus incontinence. In addition, the data collection method through anonymous self-filled questionnaires could have led to more accurate disclosure. In a retrospective chart review comparing written disclosure of symptoms to that obtained by oral interview with the physician, only 23 % of women with dual incontinence admitted the presence of flatus incontinence during interview [19]. In that same study, reporting UI was more realistic, as 86 % of women with dual incontinence or UI alone, verbally disclosed their problem. An association of AI with all five comorbidities was similarly found in the Nurses’ Health Study, a cross-sectional study of women older than 62 years [20]. A higher BMI was associated with a higher odds of one or more PFD symptoms after adjusting for confounders. This is consistent with the findings of the majority of studies, including the NHANES which evaluated women of different ethnicities in the US [6].

Improving the quality of health-care includes identifying barriers to HCS related to PFD, specifically because little is known about the “submerged part of the iceberg” which may represent a large proportion of the potentially affected population [2, 21, 22]. It is important to recognize that both determinants of and barriers to HCS behavior depend to a large extent on the geographic area, the socioeconomic conditions, and the cultural norms of the affected population. In a study evaluating Muslim Egyptian incontinent women, husband encouragement and prayer disruption were found to be the most significant factors in HCS behavior [23]. Muslim prayer must be preceded by ritual cleansing, and involves bending over, a maneuver that may lead to UI in stress-incontinent women. This results in prayer denial; thus repeated ritual cleansing and repeated prayer would be necessary. Conversely, factors associated with HCS behavior among incontinent women in the USA included symptom duration, a noticeable accident, lack of embarrassment, and keeping routine regular appointments with health-care providers [21]. Our study results are in agreement with those of other studies in concluding that age and severity of symptoms are major determinants of HCS behavior [24]. While UUI was found the be the strongest predictor for HCS in four Western European countries [25], it was not significantly associated with HCS in our study.

An interesting finding in our study was that, among women who described their PFD bother as significant, the most common deterrent to HCS was a financial constraint. This was found across all age groups and all educational levels. Lebanon’s health-care system is based on a fee for service model. More than half of the Lebanese population have health insurance through a third party, government-funded or private. qqAbout 40 % of Lebanese do not have health insurance, but they can benefit when hospitalized from substantial aid by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health irrespective of their income level [26]. It is worth noting, however, that expenses incurred during outpatient clinic (office) consultations are not totally covered by any of the mentioned parties, and are therefore considered out-of-pocket expenses. At the Medical Center where this survey was conducted, the average fees incurred during a physician consultation are the equivalent of US$85, in addition to an estimated expense of US$8 for transportation within the Beirut area (keeping in mind that the median annual household income in Lebanon was equivalent to US$13,000 in January 2014 [27]). It remains uncertain whether participants who cited financial concern as a significant obstacle to HCS assumed that such care would necessitate several costly physician visits. We intend to further investigate this point in the future by enquiring about the specific concerns of symptomatic women not seeking care.

An equally cited factor for not seeking care among women with only primary education was “a sensitive and personal problem”. This reason was significantly more frequently cited in this group compared to the other groups with higher educational levels. In a study involving 348 Egyptian incontinent women, embarrassment was the most common deterrent to HCS (67.2 %), followed by a perception of “normalcy” of UI after multiple births (46.7 %) [23]. Conversely, in a Saudi Arabian study of 379 incontinent women, only 19.4 % of the women who did not seek medical advice were too embarrassed to discuss the problem with a physician [14]. It is noteworthy that we investigated potential obstacles to seeking care via a closed questions that allowed women to choose more than one response. In other studies, open-ended questions such as “what prevented you from seeking consultation for urine leakage” have been used [23]. In yet another model, a validated tool to assess barriers to incontinence HCS was created. This used 14 questions that covered five reasons: health-care provider personnel, health-care provider site, inconvenience, fear, and cost [28]. This model was validated among ethnically diverse women in one geographic area in the state of Kentucky in the USA. As discussed above, population-specific models regarding HCS cannot be universally adopted.

Our important findings need to be considered in light of some limitations and offsetting strengths. While some of the demographic characteristics of the participants, such as prevalence of diabetes and smoking, are close to the officially reported figures in the Republic of Lebanon [10], we recognize that other characteristics, particularly the prevalence of hypertension and educational level distribution may not reflect those of the population in general. Thus, while our results are the first to shed light on the issue of PFD among women in Lebanon, they cannot be safely extrapolated to accurately reflect the distribution of symptoms and comorbidities among Lebanese women in general. Moreover, the surveys were self-filled by women while waiting for a medical appointment not related to symptoms of PFD. This may not be the ideal environment for data collection. The same limitation applies to studying HCS behavior regarding PFD in this population. Excluding those who were coming for a routine wellness clinic check-up, most participants could have had different health-care priorities that may have affected the timing of HCS related to PFD. Another limitation is that the questionnaire included separate queries about the number of vaginal deliveries (VD) and CD, but not about parity. Consequently, we were unable to correlate this variable to PFD prevalence and degree of bother. Furthermore, we could not differentiate between those with primary CD, those with CD following VD, and those with exclusively CD. Height and weight were self-reported, as is customary in most epidemiological studies, but that resulted in 30 % of our participants failing to report at least one of the two BMI parameters. It is impossible to judge how the missing BMI data could have affected the results, but we believe the bias introduced was most likely nondifferential (i.e. unrelated to PFD status or related conditions in the women surveyed). Finally, data about surgical treatment for prolapse was collected, but data on pessary use was not, as it is the experience of the authors that pessary use is infrequent in Lebanon.

The results of this study confirm that PFD symptoms are common and bothersome. An important implication is that awareness is needed both at the individual patient level and at the level of the major stakeholders in the health-care system in Lebanon, in view of the finding that financial constraint is a major obstacle to HCS.

Conclusions

Using the Arabic validated version of PFBQ to study the prevalence and degree of bother of PFD symptoms in a convenience sample of 900 women in Lebanon, our study confirms the wide variability of the prevalence of different PFD across the world, and highlights financial concerns as a common deterrent to HCS in symptomatic women, warranting further evaluation.

Abbreviations

- AI:

-

Anal incontinence

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CD:

-

Cesarean delivery

- HCS:

-

Health-care seeking

- MUI:

-

Mixed urinary incontinence

- OAB:

-

Overactive bladder

- PFBQ:

-

Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire

- PFD:

-

Pelvic floor disorder

- POP:

-

Pelvic organ prolapse

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- SUI:

-

Stress urinary incontinence

- UI:

-

Urinary incontinence

- UUI:

-

Urgency urinary incontinence

- VD:

-

Vaginal delivery

References

Dieter AA, Wilkins MF, Wu JM. Epidemiological trends and future care needs for pelvic floor disorders. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;275:380–4.

McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the urologic iceberg: design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007;52:389–96.

Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, Reilly K, Kopp Z, Herschorn S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol. 2006;50:1306–14.

Cooper J, Annappa M, Dracocardos D, et al. Prevalence of genital prolapse symptoms in primary care: a cross-sectional survey. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;26:505–10.

Walker GJA, Gunasekera P. Pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence in developing countries: review of prevalence and risk factors. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;22:127–35.

Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, Redden DT, Burgio KL, Richter HE, et al. Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:141–8.

Bazi T, Takahashi S, Ismail S, Bø K, Ruiz-Zapata AM, Duckett J, et al. Prevention of pelvic floor disorders: International Urogynecological Association Research and Development Committee opinion. Int Urogynecol J. 2016. doi:10.1007/s00192-016-2993-9.

Barber MD. Questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:461–5.

Peterson TV, Karp DR, Aguilar VC, Davila GW. Validation of a global pelvic floor symptom bother questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:1129–35.

World Health Organization. Countries: Lebanon. Beirut: World Health Organization; 2016. http://www.who.int/countries/lbn/en/. Accessed 25 June 2016.

Bazi T, Kabakian-Khasholian T, Ezzeddine D, Ayoub H. Validation of an Arabic version of the global Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2013;121:166–9.

Dooley Y, Kenton K, Cao G, et al. Urinary incontinence prevalence: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Urol. 2008;179:656–61.

Onur R, Deveci SE, Rahman S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of female urinary incontinence in eastern Turkey. Int J Urol. 2009;16:566–9.

Al-Badr A, Brasha H, Al-Raddadi R, Noorwali F, Ross S. Prevalence of urinary incontinence among Saudi women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;117:160–3.

Altaweel W, Alharbi M. Urinary incontinence: prevalence, risk factors, and impact on health related quality of life in Saudi Women. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:642–5.

Haylen BT, Ridder DD, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2009;21:5–26.

Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Thompson CL, Milsom I, Irwin D, Kopp ZS, et al. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the USA, the UK and Sweden: results from the Epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. BJU Int. 2009;104:352–60.

Awwad J, Sayegh R, Yeretzian J, Deeb ME. Prevalence, risk factors, and predictors of pelvic organ prolapse. Menopause. 2012;19:1235–41.

Dunivan GC, Cichowski SB, Komesu YM, et al. Ethnicity and variations of pelvic organ prolapse bother. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;25:53–9.

Townsend MK, Matthews CA, Whitehead WE, Grodstein F. Risk factors for fecal incontinence in older women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;108:113–9.

Kinchen KS, Burgio K, Diokno AC, et al. Factors associated with women’s decisions to seek treatment for urinary incontinence. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2003;12:687–98.

Minassian VA, Yan X, Lichtenfeld MJ, et al. The iceberg of health care utilization in women with urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:1087–93.

El-Azab AS, Shaaban OM. Measuring the barriers against seeking consultation for urinary incontinence among Middle Eastern Women. BMC Womens Health. 2010;10:3.

Apostolidis A, Nunzio CD, Tubaro A. What determines whether a patient with LUTS seeks treatment?: ICI-RS 2011. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:365–9.

O’Donnell M, Lose G, Sykes D, et al. Help-seeking behaviour and associated factors among women with urinary incontinence in France, Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom. Eur Urol. 2005;47:385–92.

Sfeir R. Strategy for national health care reform in Lebanon. 2007. http://www.fgm.usj.edu.lb/pdf/a62007.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2016.

Byblos Bank. Lebanon this week. http://www.byblosbank.com/library/files/lebanon/publications/economic%20Research/Lebanon%20This%20week/Lebanon%20This%20Week/_339.pdf. Accessed 25 Apr 2016.

Heit M, Blackwell L, Kelly S. Measuring barriers to incontinence care seeking. Neurourol Urodyn. 2008;27:174–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Appendices

Appendix 1. PFBQ

Appendix 2. Additional questions

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ghandour, L., Minassian, V., Al-Badr, A. et al. Prevalence and degree of bother of pelvic floor disorder symptoms among women from primary care and specialty clinics in Lebanon: an exploratory study. Int Urogynecol J 28, 105–118 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3080-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3080-y