Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

This study aimed to validate a symptom questionnaire to assess presence and patient bother as related to common pelvic floor disorders.

Methods

The validation of the Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire (PFBQ) included evaluation of internal reliability, test-retest reliability, and validity of the items.

Results

A total of 141 patients with mean age of 61.8 ± 13.2 were included in the study. Twenty-four percent of patients complained of stress urinary incontinence, 14.9% mixed incontinence, 14.9% urge incontinence, 10% fecal incontinence, 5.7% obstructed defecation, 28.4% pelvic organ prolapse, and 2.1% dyspareunia. The PFBQ demonstrated good reliability (α = 0.61-0.74; ICC = 0.94). There was a strong agreement beyond chance observed for each question (k = 0.77-0.91). PFBQ correlated with stage of prolapse (ρ = 0.73, p < 0.0001), number of urinary and fecal incontinence episodes (ρ = 0.81, p < 0.0001; ρ = 0.54, p < 0.0001), and obstructed defecation (ρ = 0.55, p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

The PFBQ is a useful tool that can be easily used for identification and severity or bother assessment of various pelvic floor symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Disorders of the pelvic floor encompass a variety of conditions including pelvic organ prolapse, urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, and lower urinary tract and gastrointestinal tract emptying abnormalities [1].

It is estimated that approximately 11% women will undergo surgery for prolapse or urinary incontinence during their lifetime, and surgically treated prolapse represents only the severe end of a clinical spectrum [2]. A recent study evaluating the prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women reported that nearly one quarter of women of all ages and one third of older women reported symptoms of at least one pelvic floor disorder [3]. These abnormalities share many recognized risk factors, such as vaginal delivery, heavy lifting, and nerve injury; therefore, it is common for a patient to have multiple concomitant symptomatic dysfunctions [4–6]. Although these conditions are not life threatening, they may significantly impact a woman’s quality of life and can be particularly bothersome.

In the last several years, numerous surveys focusing on pelvic floor abnormalities have been developed and are being used, mainly in research settings [7–13]. These instruments are mostly multi-item, and despite providing a rich source of information, are thus difficult to use in a clinical setting. Shorter questionnaires have been also validated, although most of them are specific for each disorder [11].

Our goal was to construct a global and concise questionnaire that can be used to identify the presence and degree of bother related to common pelvic floor problems, for use in clinical practice and for research purposes.

Patients and methods

Study design

After Institutional Review Board approval, women presenting to our pelvic floor center between October 2008 and March 2009 with pelvic floor complaints, regardless of severity, were enrolled in the study. We included patients with symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse, urinary incontinence, urinary urgency and frequency, urge incontinence, fecal incontinence, obstructed defecation, and dyspareunia. Exclusion criteria included age less than 18 years, inability to read English, or mental incapacity to complete a self-administered questionnaire.

After signing informed consent, all patients underwent a structured interview and a complete physical examination, including pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) [14] examination during their first visit. All clinical interviews were performed by a urogynecology fellow to ensure that all issues included in the questionnaire were covered. Complementary exams, such as urodynamic evaluation and anal manometry were performed as indicated to reach a final diagnosis. In addition, each patient received a voiding and a defecatory diary to complete at home.

All enrollees completed the study questionnaire entitled the “Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire (PFBQ)”, the short form of the “Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20)”, and the short form of the “Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7)” [8]. PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7 together are two validated and widely used tools in research to assess distress and quality of life for women in the field of pelvic floor disorders. The short-form of the PFDI and PFIQ were used. The PFDI has a total of 20 questions and three scales (urinary dysfunction, genital prolapse, and defecatory disorders), and the PFIQ has seven questions concerning quality of life.

To evaluate test-retest reliability, all patients received a second copy of the PFBQ in a stamped envelope and were instructed to complete and return them 1 week after the first visit.

Pelvic organ prolapse was assessed using the POP-Q system. Urinary symptoms were defined based on the International Continence Society recommendations [15]. Obstructed defecation was defined as patient-reported having to forcefully strain, press on the vagina or perineum, or digitally empty the rectum to complete the bowel movement or having the frequent feeling of incomplete evacuation. Fecal incontinence was defined as the involuntary loss of bowel function with leakage of bowel contents, including gas, liquid, or solid stool. Dyspareunia was defined as patient-reported pain or discomfort during sexual activity.

Questionnaires

The PFBQ was developed by the Cleveland Clinic Pelvic Floor staff based on clinical interviews and review of commonly used surveys, such as the Urinary Distress Inventory and the PFDI and PFIQ [7, 10]. It is a nine-item questionnaire that includes symptoms and bother related to stress urinary incontinence, urinary urgency and frequency, urge incontinence, dysuria, pelvic organ prolapse, obstructed defecation, fecal incontinence, and dyspareunia. These are considered the most commonly reported pelvic floor problems by patients presenting to a pelvic floor center. Each answer is scored in a range from 0 to 5 with higher scores indicating more severe bother. The scoring system gives the same weight for all questions. The total score ranges from 0 to 45. In order to have a summary score ranging from 0 to 100, the total score was transformed by multiplying the mean score of the answered items by 20.

The questionnaire was pilot tested in 20 patients to ensure correct interpretation and understanding of the style of the questionnaire and clarity of the questions. Different versions of the survey were shown to patients, and the questions were restructured according to patient’s suggestions for improvement. The final version of the PFBQ was then used for validation.

Statistical analysis

The validation of the PFBQ included evaluation of internal reliability, test-retest reliability, and validity of the items.

Internal reliability, which evaluates the overall correlation between items, was measured by using Cronbach’s α coefficient. A fixed effect intraclass correlation (ICC) and Lin’s concordance correlation were calculated to measure agreement between the total survey scores across testing periods, evaluating test-retest reliability. Kappa statistics were calculated to measure agreement between individual questions from the survey across testing periods.

Face validity and construct validity were determined prior to validation after initial patient interviews for identification and rewording of ambiguous phrases. Construct validity was determined by using Spearman’s correlation coefficient (ρ) to compare the survey to responses on clinical interview, clinical symptom severity assessment and final diagnosis reached. Criterion validity was evaluated comparing the PFBQ to the PFDI and PFIQ by using Kruskal-Wallis test and Wilcoxon two-sample test.

All data was managed by the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

We performed a power analysis to determine the sample size needed to demonstrate test-retest reliability for our survey by using the method described by Walter et al. [16]. Assuming that the ICC for test-retest should be greater than 0.7 (null) and assuming that our alternative ICC = 0.80, 118 subjects would be needed to detect this difference with 80% power and a one-sided α = 0.05.

Results

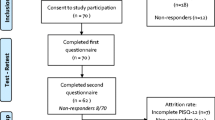

One hundred fifty-seven patients were enrolled in the study. Fifteen patients who did not complete the urinary diary and one patient who withdrew consent were excluded from the analysis. A total of 141 patients with mean age of 61.8 ± 13.2 and mean body mass index 27.65 ± 4.94 kg/m2 were included in the study. The majority of patients was White (n = 124; 88%), followed by Hispanic (n = 12; 8.5%), African American (n = 3; 2.1%), and Asian (n = 2; 1.4%). Median parity was 2 (0-8).

The most common initial presenting complaint was pelvic organ prolapse. Chief complaints and number of diagnoses per patient are represented in Table 1.

The number of concomitant symptoms reported during the clinical interview and by answers of the PFBQ was analyzed (Table 2). For urinary symptoms and prolapse, the responses to interview and to the survey were similar (p > 0.05). More patients reported fecal incontinence and dyspareunia by survey compared with interview (p < 0.001). The PFBQ took a mean of 4.6 ± 1.1 min to complete. There were no missing responses.

Evaluation of internal reliability is demonstrated in Table 3. The Cronsbach’s alpha value was obtained for the total survey and according to the population evaluated. The PFBQ proved to have good internal consistency for patients with urinary symptoms (α = 0.74), genital prolapse (α = 0.74), and defecatory disorders (α = 0.70). The internal reliability for patients with sexual dysfunction was not performed due to its small sample size (three patients with chief complaint of dyspareunia).

Table 4 shows the test-retest reliability for the PFBQ. Lin’s concordance correlation and intraclass correlation were 0.941. Both measures are very high, indicating very high test-retest reliability for the total score following a 1-week interval. The agreement for the individual questions was measured by the kappa statistics. The kappa statistics ranged from 0.77 to 0.91 indicating strong agreement for each question. The lowest agreement was observed for question 3, abnormal strong feeling of urge to urinate; while the greatest agreement was observed for question 6, feeling of a bulge in the vagina.

Table 5 represents the agreement between the PFBQ and responses to interview. All item showed positive correlations, with p < 0.0001 for all questions. The correlation with prolapse severity assessed by POP-Q examination was very good (ρ = 0.502; p < 0.0001). The correlation between stage of prolapse and PFBQ is demonstrated in Table 6. Questions regarding urinary symptoms were well correlated to the urinary diary as demonstrated by number of urinations in toilet per day (ρ = 0.583; p < 0.0001), number of urinary incontinence episodes per day (ρ = 0.811; p < 0.0001), number of urgency episodes per day (ρ = 0.594; p < 0.0001), number of urge incontinence episodes per day (ρ = 0.649; p < 0.0001), and pain/discomfort during urination (ρ = 0.410; p < 0.0001). The PFBQ also demonstrated to be significantly associated with the number of bowel movements per week (ρ = 0.513; p < 0.0001), history of straining/splinting (ρ = 0.558; p < 0.0001), and number of fecal incontinence episodes per week (ρ = 0.561; p < 0.0001). The PFBQ also showed good correlation with urinary and defecatory final diagnoses after performance of urodynamic testing and defecography (p < 0.0001).

The PFBQ scores ranged from 4 to 88. The PFDI and PFIQ scores ranged from 2.5-93 to 33-133, respectively. Overall, there was no significant difference among the three scores (p = 0.762). There were no statistically significant differences between the PFBQ and PFDI (p = 0.81) or between the PFBQ and PFIQ (p = 0.39).

Discussion

Pelvic floor disorders involve a variety of interrelated common conditions and can be a major cause of distress and bother in women. Patients’ perception of these abnormalities varies widely. Bother assessment of these disorders can be performed with history taking or by self-assessment tools. Interviewing a patient with pelvic floor disorders can be challenging, and the information obtained in a conversation may be inaccurate. Therefore, the use of a self assessment instrument can be very valuable.

In the last several years, numerous surveys have been developed for pelvic floor disorders. Most were designed to assess one form of pelvic floor dysfunction. Given the coexistence and complex interaction of pelvic floor disorders, a global instrument to assess the pelvic floor is warranted.

Two condition specific quality of life instruments, the PFDI and PFIQ were developed based on the Urinary Distress Inventory and the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire. The short forms of these questionnaires are also available and widely used mainly for research. Together, they include 27 items and include distress and quality of life.

We constructed a shorter questionnaire that can be used in both research and clinical setting. We envision the PFBQ would be given to a patient on initial evaluation visit for a pelvic floor complaint. Once completed, the questionnaire can then be used to guide in the selection of additional needed evaluation and in setting a priority ranking for management, if multiple problems are identified.

We found that some concomitant symptoms were more frequently captured on the PFBQ than by the clinical interview. Some patients only described having fecal incontinence and dyspareunia by survey rather than by interview. This supports the use of a self-assessment tool to screen for pelvic floor problems that could potentially be embarrassing for the patient.

It is important to mention that as this study was performed in a referral center, we have a relatively high fecal incontinence population; and although the questionnaire entails flatal and stool incontinence, most of the patients had stool incontinence.

The PFBQ has demonstrated good psychometric properties. As it is a short survey and each item reflects a different disorder, the internal consistency for the global survey was expected to be relatively low. We believe that constructing a long questionnaire purely to have higher internal consistency would be inappropriate, since the aim of the study was to develop a short questionnaire to be easily used in the office; and that having a good test-retest reliability, would be adequate for the survey. To ensure its reliability, the PFBQ was analyzed according to the population studied and an effort was made to have consistent test-retest reliability measures. The PFBQ had good internal consistency for patients with urinary and defecatory disorders and genital prolapse. Test-retest reliability was excellent for the global survey as well as for all individual questions.

Validation of the items demonstrated good correlation with stage of prolapse, defecatory and urinary diaries, and final diagnoses. The PFBQ also correlated well with the PFDI and PFIQ, which are used as standardized tools that evaluate distress and quality of life impact related to pelvic floor disorders. The PFBQ can be another option for researchers and clinicians to assess the presence and degree of bother of these abnormalities.

This study may be limited by the fact that we have not yet evaluated responsiveness to change.

This tool at the present time can be used as a screening questionnaire and we are in the process of performing the clinical validation portion addressing responsiveness to change.

The study was performed in patients seen in a referral center for pelvic floor distress and the vast majority of the study population was White; therefore, symptom severity may not reflect the condition of the general population. In addition, we could not evaluate internal reliability for patients with sexual dysfunction due to its relatively small sample size. Further analysis of this subpopulation will be performed.

Conclusions

The Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire is a valuable tool that is useful for the identification of and assessment of bother due to common pelvic floor disorders. The PFBQ can assess a whole spectrum of interrelated symptoms. Its ease of use and interpretation enable it to be used in the clinical setting with the added benefit of capturing issues that may not be voluntarily reported due to embarrassment.

References

Bump RC, Norton PA (1998) Epidemiology and natural history of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 25:723–746

Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL (1997) Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 89:501–506

Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, Spino C, Whitehead WE, Wu J, Brody DJ, Pelvic Floor Disorders Network (2008) Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA 300(11):1311–1316

Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD (2007) Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet 369:1027–1038

Jackson SL, Weber AM, Hull TC, Mitchinson AR, Walters MD (1997) Fecal incontinence in women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 89:423–427

Gonzalez-argente FX, Jain J, Nogueras JJ, Davila GW, Weiss EG, Wexner SD (2001) Prevalence and severity of urinary incontinence and pelvic genital prolapse in females with anal incontinence or rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum 44(7):920–926

Barber MD, Kuchibhatla MN, Pieper CF, Bump RC (2001) Psychometric evaluation of 2 comprehensive condition-specific quality of life instruments for women with pelvic floor disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol 185:1388–1395

Barber MD, Walters MD, Bump RC (2005) Short forms for two condition-specific quality of life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 & PFIQ-7). Am J Obstet Gynecol 193:103

Kelleher CJ, Cardozo LD, Khullar V, Salvatore S (1997) A new questionnaire to assess the quality of life of urinary incontinent women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 104:1374

Shumaker SA, Wyman JF, Uebersax JS et al (1994) Health-related quality of life measures for women with urinary incontinence: the incontinence impact questionnaire and the urogenital distress inventory. Qual Life Res 3:291

Uebersax JS, Wyman JF, Shumaker SA et al (1995) Short forms to assess life quality and symptom distress for urinary incontinence in women. Neurourol Urodyn 14:131

Jorge JM, Wexner SD (1993) Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 36:77

Hull TL, Floruta C, Piedmonte M (2001) Preliminary results of an outcome tool used for evaluation of surgical treatment for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 44:799–805

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P et al (1996) The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 175:10–17

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D et al (2003) The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology 61(1):37–49

Walter SD, Eliasziw M, Donner A (1998) Sample size and optimal designs for reliability studies. Stat Med 17:101–110

Acknowledgments

Gabriel P. Suciu, M.S.P.H., Ph.D. for assistance in statistical analysis.

Conflicts of interest

G. Willy Davila: Consultant and speaker: AMS, Watson, Astellas, CL Medical.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peterson, T.V., Karp, D.R., Aguilar, V.C. et al. Validation of a global pelvic floor symptom bother questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J 21, 1129–1135 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1148-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1148-7