Abstract

Purpose

The primary objective of this study was to perform an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of meniscal allograft transplantation using patient reported outcome measures at final follow-up as the outcome tool. The secondary objective was to provide an up to date review of the indications, associated procedures, operative technique, rehabilitation, failures, complications, radiological outcomes, and graft healing.

Methods

Medline, Embase and CENTRAL databases, trials registries, and Web-of Science were searched for studies using pre-defined eligibility criteria. Included studies were reviewed with Lysholm, International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) and Tegner scores, failures and complications pooled. Studies were also qualitatively assessed.

Results

There were 1,332 patients (1,374 knees) in 35 studies eligible for analysis. The mean follow-up was 5.1 years. Across all studies, Lysholm scores improved from 55.7 to 81.3, IKDC scores from 47.0 to 70.0, and Tegner activity scores from 3.1 to 4.7 between pre-operative and final follow-up assessments, respectively. The mean failure rate across all studies was 10.6 % at 4.8 years, and complication rate was 13.9 % at 4.7 years. There is a high risk of bias across the studies due to study design and missing outcomes.

Conclusion

Based on current evidence, meniscal allograft transplantation appears to be an effective intervention for patients with a symptomatic meniscal deficient knee. This should ideally be confirmed with a randomised controlled trial. There is not currently enough evidence to determine whether it is chondroprotective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The menisci have important functions in the knee including load sharing and joint stability [30, 44, 53]. Meniscal tears are the most common knee injury, with an incidence of 61 per 100,000 per year [3]. With the increased recognition of the importance of the menisci, treatment has been aimed at preserving menisci where possible [31]. However, the blood supply diminishes away from the periphery of the meniscus, which decreases the chances of a successful repair [36]. The mean failure rate of meniscal repairs was found to be 23.1 % in a recent meta-analysis [35]. Patients with a tear that is not repairable, or have had a failed repair undergo a meniscectomy.

The consequences of meniscectomy have been widely reported. A systematic review by Papalia et al. [38] found that the mean prevalence of osteoarthritis (OA) was 53.5 % (range 16–92.9 %) at a mean of 7.4 years following meniscectomy. In the same study, 39.6 % of post-meniscectomy patients had OA diagnosed radiologically, compared with 6.4 % in non-operated contralateral knees (controls). It has been shown that the amount of meniscus removed is the most important predictor for the development of OA [31, 38].

Meniscal allograft transplantation (MAT) was first performed in 1984 [34]. It has since been advocated for the treatment of post-meniscectomy symptoms, which can consist of pain, swelling, and loss of function [12, 27]. In 2011 (search performed in January 2010), a systematic review and meta-analysis showed an improvement in symptoms and function, but highlighted a lack of good-quality studies [12]. Since then, there have been a number of further studies and longer follow-up of some older studies has been reported. The primary objective of this study was to perform an updated systematic review of MAT to reflect the clinical outcomes of recently published studies. The secondary objective was to identify trend changes by systematically reviewing the indications, associated procedures, operative technique, rehabilitation, failures, complications, radiological outcomes, and graft healing.

Materials and methods

Quality of methodology

This study has been reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews [28]. Details of the systematic review protocol can be found at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO (CRD42014009134).

Eligibility criteria

Study type

-

Any case series or clinical comparative study (including randomised controlled trials) written in the English language. Biomechanical studies, case reports, and systematic reviews that do not contain new patient data were excluded.

Participants

-

Any human of any age.

Intervention

-

Meniscal allograft transplantation using any allograft preserving method and any grafting type.

-

Any rehabilitation regime post-operatively.

Comparator

-

If a comparator group exists, it should be a reasonable alternative treatment to MAT or a difference in MAT methodology, for example different allograft fixation technique.

Outcome measures

-

A study must include a PROM at a minimum of 1 year post-operatively for every patient. Commonly used PROMs include Lysholm, International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC), and Tegner activity index, but any other PROM was accepted.

Search strategy

A search was undertaken for both published and unpublished studies. The design of the search strategy was sensitivity maximising in order to reduce the risk of missing eligible studies. The published search strategy was developed using a combination of keywords and ‘subject headings’, which were exploded to maximise the inclusion of potentially relevant studies. The databases of Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid) and the Cochrane library (CENTRAL) were searched (Tables 1, 2, 3, respectively). The references of eligible studies and previous systematic reviews were searched for other potentially relevant studies. Unpublished studies were searched according to recommendations from a recent article published in the British Medical Journal [9]. The World Health Organisation International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/) and Clinical Trials Registry (http://clinicaltrials.gov) were searched for ongoing or complete trials. The ‘Web-of Science’ (http://thomsonreuters.com/web-of-science/) was searched for conference proceedings.

Selection and appraisal method

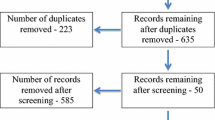

Figures 1 and 2 show flow diagrams of the selection processes for published and unpublished studies, respectively. Results of the database searches were transferred into EndNote, and duplicates were automatically discarded. Our pre-defined criteria were used to assess the eligibility of the remaining studies from their title and abstract. The full papers of the remaining studies were then reviewed.

Data from eligible studies were extracted, and studies that contained some or all of the same patients were grouped. In order to reduce the risk of duplicate publication bias [23], the study with the longest mean follow-up was included in the analysis, with the other studies cited in the references but excluded from further analysis.

Failures and complications were collected as reported by each study. If failures were not specifically defined, a failure was considered to be either the complete removal of the allograft, revision MAT, or conversion to joint replacement. If complications were not defined, a complication was considered to be any reported adverse event that the patient experiences.

Results

There were 1,332 patients (1,374 knees) in 35 studies included in this systematic review (Table 4). There were no prospective controlled trials (randomised or otherwise), eligible for inclusion. The follow-up range across all studies was from 1 to 20 years, with a mean of 5.1 years. The youngest and eldest patients were 13 [37] and 69 [47] years old, respectively, with a mean age across all studies of 33.7 years. Of the 1,332 patients, 762 were male and 343 were female; the gender was not reported for 227 patients. There were 587 medial and 657 lateral allografts across all studies.

Patient reported outcome measures

The Lysholm score is graded from 0 (worst) to 100 (best) and was designed to assess outcomes following knee ligament surgery [50]. It was the most commonly used PROM, being used in 25 studies. The mean pre-operative score was 55.7, and at final follow-up, the mean score was 81.3 (Fig. 3). A poor score is considered to be under 65, fair 65–83, good 84–90, and excellent over 90. Using these measures, the average pre-operative score was easily within the ‘poor’ range. At final follow-up, the score was ‘fair’, although close to the ‘good’ range.

The IKDC subjective knee form evaluates symptoms and function in activities of daily living [20]. It was initially designed to assess ligament disruption in the knee, but has been shown to be useful for a broad range of knee pathologies [17]. The range is from 0 (worst) and 100 (best). It was used in 12 studies, with pre-operative and final follow-up scores of 47.8 and 70, respectively (Fig. 4). These scores are consistent with the improvement seen in Lysholm scores, as pre-operative scores are very low for a young patient population, and final follow-up scores are significantly better, but not near the best possible score.

The Tegner activity level scale is a single score from 0 (worst) to 10 (best) that denotes the highest activity level that the patient can perform [50]. It was used in 11 studies with pre-operative and final follow-up scores of 3.1 and 4.7, respectively (Fig. 5).

Some studies used other PROMs such as the Fulkerson questionnaire [6], SF 36 [39], Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) [52], Knee Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) [18], Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) [48], as well as pain and activities of daily living scores [37]; these showed improvements broadly in line with the more commonly used PROMs (results not shown).

Indications

The most frequently reported indications for MAT were a symptomatic (pain, swelling or stiffness) knee and a previous total or near total meniscectomy. Most studies did not define the extent of meniscectomy, although Farr et al. [13] said that it should be within 3 mm of the posterior horn. Most studies included an upper age limit or described eligible patients as ‘young’. Only two studies included patients over 55 years old [25, 49]. Severe cartilage damage or osteoarthritis was exclusion criteria for a significant number of studies [10, 16, 21, 24, 25, 29, 39, 41, 46, 57], although were inclusion criteria for a limited number of other studies [4, 6, 14]. Normal alignment and/or a stable knee was a common requirement; this could usually be corrected intraoperatively [10, 16, 24, 25, 29, 39, 40, 46].

Graft type

The graft type was known in 1,186 allografts. There were 796 fresh frozen, 269 cryopreserved, 100 fresh, and 21 lyophilised allografts used across all studies. Although cryopreserved and fresh frozen grafts were used in roughly equal numbers until 2010 [12], all studies published since then have used fresh frozen grafts, with the exception of a long-term follow-up case series of 4 grafts [1, 5, 8, 18, 24–26, 29, 57]. This represents a significant change in practice from the previously reported systematic review by Elattar et al. [12]. Grafts in earlier studies were irradiated [6, 37], but this practice has now stopped.

Operative technique

The surgical technique was described in 1,263 allografts. Earlier studies used an open technique, with collateral ligament detachment or joint distraction [6, 42, 51, 55]. Once an arthroscopic-assisted technique had been pioneered, it quickly became the technique of choice. Bone bridge or plug fixation for the meniscal roots was the most common method, being used in 904 allografts (across 26 studies), whereas an all suture technique was used in 359 allografts (across 13 studies). One study found more cases of major extrusion on MRI with their soft tissue fixation than their bone plug fixation, although PROMs were not significantly different between the groups [1].

Associated procedures

Other knee procedures performed at the time of MAT were common. The inclusion criteria for a number of studies were a stable knee with normal alignment, which was often corrected intraoperatively with an osteotomy ± ACL reconstruction. Other commonly reported procedures included articular cartilage repair procedures including autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) and microfracture. Only 243 allografts were clearly performed as isolated procedures, although this is likely to be higher as reporting of isolated MAT in some studies was either not clear or not described.

Rehabilitation

Although there were variations in post-operative rehabilitation, most studies reported a post-operative period of either partial or non-weight bearing and a restriction on flexion from 0° to between 60° and 90°. Most studies had allowed full weight bearing by 6 weeks, with a gradual progression to running by 3–6 months. Return to full pivoting/cutting sports was controversial with some studies recommending lifelong limits [16, 39, 45, 46, 56]. However, it was more common to allow return to full sports, usually after 6–12 months [2, 5, 8, 14, 24, 29, 40, 47, 48, 52]. Stone et al. [48] reported no correlation with post-operative sporting level and failure in patients with a high pre-injury activity level.

Failures and complications

The most common definition of failure was conversion to a joint replacement or excision of the allograft. There were 6 studies (198 allografts) that did not show evidence of reporting possible failures [5, 26, 41, 45, 46, 56]. Therefore, there were a total of 128 failures in 1,174 allografts implanted at a mean of 4.8 years across included studies (10.9 % failure rate). The study with the highest number of failures had 29 out of 96 allografts at 2 year follow-up [37].

Complications were varied and included infection, synovitis, meniscal tears, and partial meniscal detachments. Complications ascribed to concomitant procedures such as osteotomy or anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction were also common. Six studies (238 allografts) did not report complications [7, 26, 41, 45, 46, 56]. Therefore, there were 154 complications in 1,134 allografts at a mean of 4.7 years across included studies (13.6 % complication rate).

Radiological findings

Only a limited number of studies reported radiographic progression of osteoarthritis findings at follow-up. One study reported no change in Kellgren and Lawrence OA grade in 28 out of 36 knees on plain radiographs at a mean follow-up time of 2.6 years [16]. One study reported no joint space narrowing [15], while other studies reported small reductions in joint space at final follow-up [18, 21, 39]. Two studies compared the joint spaces of the same compartment in the contralateral knee and found no statistically significant changes at baseline and final follow-up in either compartment [39, 45].

Meniscal extrusion was a common MRI finding, with most studies reporting either a mean extrusion of more than 3 mm or the majority of allografts classified as ‘extruded’ or ‘major’ extrusion [1, 16, 18, 24–26, 29].

Graft healing

Ha et al. [16] performed second look arthroscopy at an average of 26.3 months for various reasons. They found that 11 had completely healed to the capsule, while 7 had partially detached; there were no cases of complete detachment. Rath et al. found that all 10 allografts undergoing post-operative arthroscopy had completely healed to the capsule, and Wirth et al. found that 17 of 19 allografts had completely healed at post-operative arthroscopy [39, 55].

Hardy et al. [18] performed MRIs on 14 of 21 patients at 6 months post-operatively, finding 57.1 % total healing, 14.3 % partial healing, and 28.6 % no healing according to the Henning criteria. Noyes et al. [37] devised a new score for graft healing using MRI and arthroscopy, reporting a 40 % complete or partial healing rate.

Risk of bias

-

Missing studies

There were no completed registered trials on any searched registry. Only studies written in the English language were reviewed; therefore, some otherwise eligible studies may not have been included.

-

Study type

All studies included in this systematic review were case series. Some studies described control groups, but the selection for each intervention was for specific reasons, such as a change of technique part way through the study [1]. Therefore, there is a high risk of selection bias in all included studies. A large number of studies were retrospective, which increases the risk of measurement error (Table 4).

-

Missing outcomes

A number of studies did not report failures or complications. These were not included in the analysis of average complication and failure rate. A number of studies specifically excluded patients that had a ‘failed’ treatment from the analysis of PROMs [10, 13, 43]. It is likely that patients with failed treatments would have worse PROMs scores. Moreover, complications or failures were commonly not defined. It is therefore unknown whether some studies did not consider some patients to have had a complication or failure when others did.

Discussion

The most important finding is that there are significant improvements in all mean PROMs at final follow-up. The baseline PROMs scores are very low considering the young patient group, which indicates the severity of symptoms in patients undergoing MAT. It is also important to note that although there are significant gains in PROMs at final follow-up, mean scores are still well below top scores in this young patient group. This may reflect either non-modifiable damage to the knee or the failure of treatment to completely reverse symptoms.

Despite this systematic review containing many new studies, the results are roughly comparable with older systematic review results [11, 12, 19]. In addition to the weighted means of the outcome measures, most studies showed significant improvements in PROMs, with an acceptable complication and failure rate. This is the strongest evidence to date for the efficacy of MAT in patients with a symptomatic meniscal deficient knee. Future studies must have an improved methodology and reporting quality and ideally have a prospective control group. The relatively low volume of MAT compared with more common operations makes randomised trials more difficult.

One trend change in newer studies has been the more common usage of fresh frozen allografts over other preservative methods. Cryopreservation involves controlled freezing to around −196 °C with the meniscus bathed in cryoprotectant and then thawed under strict protocols. There is no strong evidence that cryopreservation maintains the integrity of the meniscal allograft better than fresh freezing [32]. Cryopreservation also requires strict thawing protocols, which are difficult to achieve in the clinical environment. These factors may have contributed to the increased use of fresh frozen allografts.

Another controversy is the method of meniscal root fixation. This systematic review shows that bone plug or bone bridge fixation remains the most popular method, although an all suture technique through bone tunnels is used in significant numbers. Abat et al. [1] reported more cases of major meniscal extrusion on MRI in patients that had suture fixation of grafts when compared to bone plug fixation. However, inferences from this should be drawn with caution as the two groups were not directly comparable and should thus be considered as parallel case series. Bone fixation is often done in the hope that it provides a stronger fixation, while an all suture technique is less technically demanding. A biomechanical study has shown a similar pull-out strength with either technique [22], whereas another showed that a suture only technique allows a slightly higher contact pressure on the tibial cartilage [33].

In general, the quality of evidence was low, with the vast majority of studies being case series. Due to the low quality of studies, there is a high risk of biased results. Patients that were described as having a failed treatment were often excluded from analysis, which could lead to an overestimation of the benefit of treatment. The wide variation in failures and complications also suggests that some reporting was more detailed than others. Therefore, failures and complications may also be underreported.

Indications for MAT varied among studies, but all studies required patients to have a symptomatic meniscal deficient compartment of the knee. Therefore, the success or failure of the treatment may be judged against symptom relief, as judged by PROMs. However, many studies refer to the potential for MAT to reduce the risk of OA in these patients. This systematic review did not find strong evidence to support or refute this hypothesis.

Conclusion

This systematic review shows a consistent and significant improvement in all used PROMs for MAT at final follow-up. The low pre-operative scores and young patient group indicate that there is a significant disease burden that appears to be improved by MAT. A future randomised controlled trial would be able to provide definitive evidence of its effectiveness.

References

Abat F, Gelber PE, Erquicia JI, Pelfort X, Gonzalez-Lucena G, Monllau JC (2012) Suture-only fixation technique leads to a higher degree of extrusion than bony fixation in meniscal allograft transplantation. Am J Sports Med 40(7):1591–1596

Alentorn-Geli E, Vazquez RS, Diaz PA, Cusco X, Cugat R (2010) Arthroscopic meniscal transplants in soccer players: outcomes at 2- to 5-year follow-up. Clin J Sport Med 20(5):340–343

Baker P, Peckham A, Pupparo F, Sanborn J (1985) Review of meniscal injury and associated sports. Am J Sports Med 13:1–4

Bhosale AM, Myint P, Roberts S, Menage J, Harrison P, Ashton B, Smith T, McCall I, Richardson JB (2007) Combined autologous chondrocyte implantation and allogenic meniscus transplantation: a biological knee replacement. Knee 14(5):361–368

Binnet MS, Akan B, Kaya A (2012) Lyophilised medial meniscus transplantations in ACL-deficient knees: a 19-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20(1):109–113

Cameron JC, Saha S (1997) Meniscal allograft transplantation for unicompartmental arthritis of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res 337:164–171

Carter T, Rabago M (2012) Meniscal allograft transplantation: 10 year follow-up. Arthroscopy 1:e17–e18

Chalmers PN, Karas V, Sherman SL, Cole BJ (2013) Return to high-level sport after meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy 29(3):539–544

Chan AW (2012) Out of sight but not out of mind: how to search for unpublished clinical trial evidence. Br Med J 344:d8013

Cole BJ, Dennis MG, Lee SJ, Nho SJ, Kalsi RS, Hayden JK, Verma NN (2006) Prospective evaluation of allograft meniscus transplantation: a minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 34(6):919–927

Crook TB, Ardolino A, Williams LA, Barlow IW (2009) Meniscal allograft transplantation: a review of the current literature. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 91(5):361–365

Elattar M, Dhollander A, Verdonk R, Almqvist K, Verdonk P (2011) Twenty-six years of meniscal allograft transplantation: is it still experimental? A meta-analysis of 44 trials. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19(2):147–157

Farr J, Rawal A, Marberry KM (2007) Concomitant meniscal allograft transplantation and autologous chondrocyte implantation: minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 35(9):1459–1466

Gomoll AH, Kang RW, Chen AL, Cole BJ (2009) Triad of cartilage restoration for unicompartmental arthritis treatment in young patients: meniscus allograft transplantation, cartilage repair and osteotomy. J Knee Surg 22(2):137–141

Gonzlez-Lucena G, Gelber PE, Pelfort X, Tey M, Monllau JC (2010) Meniscal allograft transplantation without bone blocks: a 5- to 8-year follow-up of 33 patients. Arthroscopy 26(12):1633–1640+e1214

Ha JK, Shim JC, Kim DW, Lee YS, Ra HJ, Kim JG (2010) Relationship between meniscal extrusion and various clinical findings after meniscus allograft transplantation. Am J Sports Med 38(12):2448–2455

Hambly K, Griva K (2008) IKDC or KOOS? Which measures symptoms and disabilities most important to postoperative articular cartilage repair patients? Am J Sports Med 36(9):1695–1704

Hardy PP, Roumazeille T, Klouche S, Rousselin B, Bongiorno V, Graveleau N, Billot N, Pansard E (2013) Arthroscopic meniscal allograft transplantation without bone blocks: evaluation with mr-arthrography. In: 9th biennial congress of the international society of arthroscopy, Knee Surgery, and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine Toronto, Canada, 12–16 May 2013

Hergan D, Thut D, Sherman O, Day MS (2011) Meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy 27(1):101–112

Higgins L, Taylor M, Park D, Ghodadra N, Marchant M, Pietrobon R, Cook C (2007) Reliability and validity of the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective knee form. Joint Bone Spine 74(6):594–599

Hommen JP, Applegate GR, Del Pizzo W (2007) Meniscus allograft transplantation: ten-year results of cryopreserved allografts. Arthroscopy 23(4):388–393

Hunt S, Kaplan K, Ishak C, Kummer FJ, Meislin R (2008) Bone plug versus suture fixation of the posterior horn in medial meniscal allograft transplantation: a biomechanical study. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 66(1):22–26

Huston P, Moher D (1996) Redundancy, disaggregation, and the integrity of medical research. Lancet 347(9007):1024–1026

Jang SH, Kim JG, Ha JG, Shim JC (2011) Reducing the size of the meniscal allograft decreases the percentage of extrusion after meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy 27(7):914–922

Kim J-M, Lee B-S, Kim K-H, Kim K-A, Bin S-I (2012) Results of meniscus allograft transplantation using bone fixation: 110 cases with objective evaluation. Am J Sports Med 40(5):1027–1034

Koh YG, Moon HK, Kim YC, Park YS, Jo SB, Kwon SK (2012) Comparison of medial and lateral meniscal transplantation with regard to extrusion of the allograft, and its correlation with clinical outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br 94(B 2):190–193

LaPrade RF, Wills NJ, Spiridonov SI, Perkinson S (2010) A prospective outcomes study of meniscal allograft transplantation. Am J Sports Med 38(9):1804–1812

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000100

Marcacci M, Zaffagnini S, Muccioli GM, Grassi A, Bonanzinga T, Nitri M, Bondi A, Molinari M, Rimondi E (2012) Meniscal allograft transplantation without bone plugs: a 3-year minimum follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 40(2):395–403

Markolf K, Mensch J, Amstutz H (1976) Stiffness and laxity of the knee: the contributions of the supporting structures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 58(A):583–594

McDermot I, Amis AA (2006) The consequences of meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br 88(B):1549–1556

McDermott ID (2010) What tissue bankers should know about the use of allograft meniscus in orthopaedics. Cell Tissue Bank 11(1):75–85

McDermott ID, Lie DT, Edwards A, Bull AM, Amis AA (2008) The effects of lateral meniscal allograft transplantation techniques on tibio-femoral contact pressures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 16(6):553–560

Milachowski KA, Weismeier K, Wirth CJ (1989) Homologous meniscus transplantation. Experimental and clinical results. Int Orthop 13(1):1–11

Nepple JJ, Dunn WR, Wright RW (2012) Meniscal repair outcomes at greater than five years: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 94(24):2222–2227

Newman AP, Daniels AU, Burks RT (1993) Principles and decision making in meniscal surgery. Arthroscopy 9(1):33–51

Noyes F, Barber-Westin S (1995) Irradiated meniscus allografts in the human knee. A two to five year follow-up study. Orthop Trans 19:417

Papalia R, Del Buono A, Osti L, Denaro V, Maffulli N (2011) Meniscectomy as a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Br Med Bull 99:89–106

Rath E, Richmond JC, Yassir W, Albright JD, Gundogan F (2001) Meniscal allograft transplantation. Two- to eight-year results. Am J Sports Med 29(4):410–414

Rue JPH, Yanke AB, Busam ML, McNickle AG, Cole BJ (2008) Prospective evaluation of concurrent meniscus transplantation and articular cartilage repair: minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 36(9):1770–1778

Rueff D, Nyland J, Kocabey Y, Chang HC, Caborn DN (2006) Self-reported patient outcomes at a minimum of 5 years after allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with or without medial meniscus transplantation: an age-, sex-, and activity level-matched comparison in patients aged approximately 50 years. Arthroscopy 22(10):1053–1062

Ryu RKN, Dunbar WHV, Morse GG (2002) Meniscal allograft replacement: a 1-year to 6-year experience. Arthroscopy 18(9):989–994

Saltzman BM, Bajaj S, Salata M, Daley EL, Strauss E, Verma N, Cole BJ (2012) Prospective long-term evaluation of meniscal allograft transplantation procedure: a minimum of 7-year follow-up. J Knee Surg 25(2):165–175

Seedholm B, Dowson D, Wright V (1974) Functions of the menisci: a preliminary study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 56(B):381–382

Sekiya JK, Giffin JR, Irrgang JJ, Fu FH, Harner CD (2003) Clinical outcomes after combined meniscal allograft transplantation and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 31(6):896–906

Sekiya JK, West RV, Groff YJ, Irrgang JJ, Fu FH, Harner CD (2006) Clinical outcomes following isolated lateral meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy 22(7):771–780

Stollsteimer GT, Shelton WR, Dukes A, Bomboy AL (2000) Meniscal allograft transplantation: a 1- to 5-year follow-up of 22 patients. Arthroscopy 16(4):343–347

Stone KR, Pelsis J, Surrette S, Stavely A, Walgenbach AW (2013) Meniscus allograft transplantation allows return to sporting activities. In: Arthroscopy. Toronto, pp e52–e53

Stone KR, Walgenbach AW, Turek TJ, Freyer A, Hill MD (2006) Meniscus allograft survival in patients with moderate to severe unicompartmental arthritis: a 2- to 7-year follow-up. Arthroscopy 22(5):469–478

Tegner Y, Lysholm J (1985) Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res 198:43–49

van der Wal RJP, Thomassen BJW, van Arkel ERA (2009) Long-term clinical outcome of open meniscal allograft transplantation. Am J Sports Med 37(11):2134–2139

Verdonk R, Verdonk P, Almqvist KF (2009) Viable meniscal transplantation. Revista Brasileira de Medicina 66(8):37–41

Voloshin A, Wosk J (1983) Shock absorption of meniscectomized and painful knees: a comparative in vivo study. J Biomed Eng 5:157–161

Vundelinckx B, Bellemans J, Vanlauwe J (2010) Arthroscopically assisted meniscal allograft transplantation in the knee: a medium-term subjective, clinical, and radiographical outcome evaluation. Am J Sports Med 38(11):2240–2247

Wirth CJ, Peters G, Milachowski KA, Weismeier KG, Kohn D (2002) Long-term results of meniscal allograft transplantation. Am J Sports Med 30(2):174–181

Yoldas EA, Sekiya JK, Irrgang JJ, Fu FH, Harner CD (2003) Arthroscopically assisted meniscal allograft transplantation with and without combined anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 11(3):173–182

Zhang H, Liu X, Wei Y, Hong L, Geng XS, Wang XS, Zhang J, Cheng KB, Feng H (2012) Meniscal allograft transplantation in isolated and combined surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20(2):281–289

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Arthritis Research UK (Grant Number 20149).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

This study does not contain new patient data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, N.A., MacKay, N., Costa, M. et al. Meniscal allograft transplantation in a symptomatic meniscal deficient knee: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23, 270–279 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-014-3310-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-014-3310-0