Abstract

Hypoxia is a common micro-environmental stress which is experienced by cells during a range of physiologic and pathophysiologic processes. The identification of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) as the master regulator of the transcriptional response to hypoxia transformed our understanding of the mechanism underpinning the hypoxic response at the molecular level and identified HIF as a potentially important new therapeutic target. It has recently become clear that multiple levels of regulatory control exert influence on the HIF pathway giving the response a complex and dynamic activity profile. These include positive and negative feedback loops within the HIF pathway as well as multiple levels of crosstalk with other signaling pathways. The emerging model reflects a multi-level regulatory network that affects multiple aspects of the physiologic response to hypoxia including proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation. Understanding the interplay between the molecular mechanisms involved in the dynamic regulation of the HIF pathway at a systems level is critically important in defining new appropriate therapeutic targets for human diseases including ischemia, cancer, and chronic inflammation. Here, we review our current knowledge of the regulatory circuits which exert influence over the HIF response and give examples of in silico model-based predictions of the dynamic behaviour of this system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The development of molecular machineries capable of utilizing atmospheric oxygen for bioenergetic purposes (e.g. oxidative phosphorylation) was a key event in the evolution of life on Earth. This, along with other processes such as the development of membrane compartmentalisation, allowed eukaryotic organisms to greatly increase their metabolic efficiency. This enabled the development of a range of biochemical processes which provided the bioenergetic capacity to permit the evolution of more complex life forms such as metazoans [1]. However, this also led to a high degree of dependence of most eukaryotic cells upon a constant supply of oxygen in order to maintain metabolic homeostasis and cell, tissue, and organism survival. Hypoxia, which occurs when oxygen demand exceeds supply, is a relatively common occurrence in health and disease [2]. It may occur in response to physiologic stimuli such as ascent to high altitude or exercise or as a result of diseases such as cancer, chronic inflammation, or vascular disease. The critical dependence on oxygen for metabolic homeostasis and survival led to the early evolution of molecular mechanisms that enabled cells, tissue, and organisms to adapt to hypoxia. These adaptive responses include fundamental changes in cellular metabolism primarily orchestrated by the helix-loop-helix (HLH) transcription factor family member termed hypoxia inducible factors (HIF).

To date, three HIF family members have been identified in mammals (HIF-1, HIF-2, and HIF-3) of which the best characterized is the HIF-1 [3]. HIF-1 is composed of discrete alpha and beta subunits (HIF-1α and HIF-1β, respectively) both of which are ubiquitously expressed in human tissues [4, 5]. While HIF-1β (also known as the aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator, ARNT) is stably expressed, the HIF-α subunits are continuously degraded by the 26S proteasome under physiologic conditions, thus preventing HIF activity in normoxia. In hypoxia, degradation of HIF-α is inhibited, and the α and β subunits dimerize, translocate to the nucleus, and activate the expression of a family of genes which facilitate cellular adaptation to hypoxia.

The mechanism underpinning the activation of HIF in hypoxia was first elucidated in 2002 and involves the inhibition of the oxygen-dependent hydroxylation of HIF-α subunits by a family of HIF-hydroxylases. To date, three HIF-regulating prolyl-4-hydroxylases (PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3) have been identified in mammalian cells [6]. They utilize molecular oxygen and the Krebs cycle (TCA cycle) intermediate α-ketoglutarate as co-substrates to hydroxylate HIF-α subunits at conserved prolyl residues [7, 8]. This increases the α subunit’s affinity for the von Hippel-Lindau protein (pVHL), a member of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [9]. The pVHL-mediated ubiquitylation leads to constitutive proteasomal degradation of the HIF-α subunit. In hypoxia, PHD activity is reduced due to the lack of available oxygen, resulting in stabilization and formation of the active HIF heterodimer. A second level of hydroxylation-dependent regulation of HIF is mediated by the asparagine hydroxylase termed factor inhibiting HIF (FIH) which prevents HIF’s interaction with the transcriptional co-activator p300/CBP [10–12]. The adaptive programmes activated by HIF include the metabolic switch from the oxygen-dependent oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, increased angiogenesis, and erythropoiesis. Therefore, HIF represents a key regulator of the metazoan transcriptional response to hypoxia which plays a key role both in physiology and disease. Appreciating the dynamic nature of this pathway is critical to our future understanding of adaptation to hypoxia and targeting the underlying pathways for therapeutic benefit.

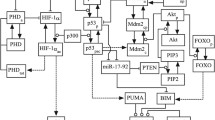

While the canonical pathway regulating the activity of HIF (as outlined above) is the key link between hypoxic sensing and the activation of an adaptive transcriptional response, a range of other inputs are also involved in shaping the spatial and temporal nature of the HIF response (Fig. 1). It is likely that such inputs confer upon HIF a richly dynamic activity profile allowing a high degree of selectivity in terms of context-dependent gene expression profiles. These inputs include feedback loops within the HIF pathway as well as crosstalk with other signaling pathways representing a high degree of complexity.

Multiple interactions in the HIF pathway. Besides the canonical PHD-mediated effects, various additional signals can influence the HIF activity via extensive interactions between the HIF and other pathways. This complex regulatory network enables HIF to integrate a wide range of extracellular stimuli and the modulation of the HIF-mediated adaptive responses to hypoxia according to the demands posed by the variable extracellular milieu. Green arrows and red connectors indicate positive (e.g. induction or activation) and negative (inactivation) effects, respectively. Dashed arrows indicate indirect or putative interactions

The intricate nature of these regulatory systems necessitates novel analytic techniques such as mathematical modeling. Since it was done recently, reviewing the mathematical modeling efforts on HIF signaling in its entirety is beyond the scope of this work [13–16]. Instead here, we review those sufficiently characterized HIF interactors that are considered to play key roles in the regulation of the HIF-orchestrated hypoxic response. In addition, we would like to demonstrate the potential power of the model-based approach in disentangling HIF complexity by attempting to answer a series of questions using simplified mathematical models. Through these practical examples, we hope to highlight the type of questions one can ask and how one may go about interrogating the models to reach answers.

Feedback loops in the HIF pathway

Physiologic Feedback

Upon experiencing systemic hypoxia, coordinated multi-organ measures are deployed to survive the hypoxic insult and restore oxygen homeostasis. These include attempts to increase the oxygen supply through elevated erythropoiesis and/or neovascularization both governed by HIF-inducible genes. At a systemic level, hypoxia-activated HIF induces erythropoietin (EPO) expression in interstitial kidney and liver cells that subsequently increases erythropoiesis in the bone marrow [17, 18]. In addition, HIF-driven increase of the serum erythropoietin levels represses the HAMP gene that encodes the hepatocyte-specific iron homeostasis regulator hepcidin [19–21]. The subsequent drop of serum hepcidin results in elevated iron release from the intestinal epithelium supplying the increased iron demand of the expanded erythropoiesis [22]. The consequently elevated oxygen and iron supply, however, may also provide prolyl-4-hydroxylases their co-substrates, thus promoting a systemic physiological negative feedback loop in the HIF system [23].

At the tissue level, another negative feedback loop is mediated by the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) that may limit the HIF response. HIF-induced VEGF and their cognate receptors act on the vascular endothelial cells to promote angiogenesis that further supports oxygen supply to the hypoxic tissues [3, 24, 25]. These HIF-orchestrated adaptive measures ultimately lead to increased tissue oxygenation which overcomes the causative hypoxic insult resulting in physiologic negative feedback loops (Fig. 2a).

Connected feedback loops in HIF regulation. a Simplified overview of the PHD-mediated regulatory feedbacks of HIF-α proteins. Binding of active HIF to its consensus sequences (HRE) is under the control of multiple, interlocked feedback loops mediated by HIF target gene products and metabolic intermediates alike. b–f Role of PHD isoforms in shaping HIF-1α transient dynamics. b, c, d, e Model simulations of HIF-1α time course in response to hypoxia exposure at time 0 for different values of the indicated parameters. The system was modeled to reach steady state in normoxia first before being exposed to hypoxia. f Dose-response simulation of dependence of steady-state HIF-1α on increasing feedback strength of the PHD2- and PHD3-mediated feedbacks. Details of the model equations and values used for plotting are given in the Appendix (or Supplementary Material). g–k miR-155 vs. PHD2 in shaping HIF-1α transient dynamics. g–j Model simulations of HIF-1α time course in response to hypoxia exposure at time 0 for different values of the indicated parameters. The system was modeled to reach steady state in normoxia first before being exposed to hypoxia. k A 3D simulation plot showing the dependence of steady-state HIF-1α fold change (hypoxia vs. normoxia) on miR-155-HIF-1α binding and HIF-1α protein degradation rate. Details of the model equations and values used for plotting are given in the Appendix (or Supplementary Material). All species units are in nM

Metabolic Feedback

At the cellular level, hypoxia-activated HIF rewires metabolism and renders it less oxygen dependent by regulating a cluster of metabolic enzyme-encoding genes [26]. Some of these have also been found to regulate HIF activity forming metabolic feedback loops in the HIF system. A prototype of such a loop is pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-1 (PDK-1) which phosphorylates pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). PDH fuels the mitochondrial TCA cycle via conversion of pyruvate to the TCA cycle substrate acetyl-coenzyme A (ac-CoA) [27]. PDK-1 mediates inactivating phosphorylation of PDH shutting down the ac-CoA supply of the TCA cycle. This leads to fundamental changes in mitochondrial functions including the accumulation of TCA cycle intermediates [28]. Since HIF-regulating prolyl-4-hydroxylases utilise α-ketoglutarate as a co-substrate and produce succinate during their catalytic activity, it is not surprising that the accumulation of succinate blocks these hydroxylases [29]. Indeed, loss-of-function mutations in succinate dehydrogenase were found to be inhibitory towards PHDs leading to the stabilisation of HIF-α subunits and succinate was identified as the mediator of this effect [30, 31]. Thus, PHDs can also integrate metabolism-dependent stimuli in the regulation of HIF-α which, in return, induces a panel of adaptive genes forming a classical feedforward loop.

Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 like (GPD1-L), another metabolic enzyme indirectly regulated by HIF, has also been suggested to act on the prolyl hydroxylase-mediated limitation of HIF function. GPD1-L has enzymatic activity similar to the mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase that catalyses the redox conversion of glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) to dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DAP) and is believed to connect oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis and lipogenesis via the regulation of the amount of the cytosolic G3P [32]. The microRNA-210 (miR-210)-mediated silencing of GPD1-L was found to decrease the rate of PHD-mediated HIF-1α degradation, and this effect was reversed by pharmacological inhibition of the proteasome or PHD activities [33]. GPD1-L, however, is not the only metabolic enzyme that affects HIF stability via its microRNA-mediated regulation. In hypoxia, miR-183 targets isocitrate dehydrogenase, the TCA cycle mediator that produces α-ketoglutarate from isocitrate. Due to the α-ketoglutarate-dependent nature of the prolyl-4-hydroxylases, the miR-183-mediated blockade of the α-ketoglutarate production favours HIF-α stabilisation via inhibition of PHDs [34]. Although the mechanism of hypoxic upregulation of miR-183 is yet to be determined, miR-210 has already shown to be HIF-1-inducible. Thus, both the HIF-inducible PDK-1 and miR-210 complete synergistic metabolic positive feedback loops within the HIF pathway targeting the primary HIF repressor prolyl-4-hydroxylases [35] (Fig. 2a).

Which PHD isoforms control the transient dynamics of HIF-1α?

The transient dynamics of HIF-1α protein expression in response to a hypoxic insult has been observed in multiple cell types [13, 14]. Since such an adaptive response profile is often underpinned by negative feedback regulation, PHD-mediated feedback loops have long been thought to be the underlying mechanisms. However, the fact that both PHD2 and PHD3 form negative feedback loops with HIF-1α posed questions of whether they are functionally redundant, and if not, how individual isoforms are different in modulating HIF timing, duration, and signaling amplitude. To probe these questions, we adapted a model recently developed by Bagnall et al. which was trained using single-cell imaging data of HIF dynamic profiles [36]. The schematic diagram of this model is given in Fig. 2a and Figure S1. Detailed model information is presented in the Supplementary Materials (SM). A major advantage of having a model is that one can analyze and predict how a particular signaling output depends on changes of certain biological factors in the modeled system. Techniques such as sensitivity analysis allow us to do just that.

First, we theoretically vary the parameter controlling PHD2-mediated feedback strength and simulate the corresponding HIF-1α response to hypoxia. The model predicts that strong feedback induces not only a lower steady-state level of HIF-1α response but also a lower peak amplitude and shorter peak duration (Fig. 2b). A similar analysis for the PHD3-mediated feedback, however, shows a much less pronounced effect. While varying, the feedback strength mildly affects the response peak, such change does not seem to influence steady-state level of HIF-1α (Fig. 2d). This observation is further supported by dose-response simulations showing that the steady-state level of HIF-1α exponentially depends on the PHD2-mediated feedback strength while it is relatively insensitive to change in feedback strength mediated by PHD3 (Fig. 2f). These simulations are in agreement with the conclusions in previous reports suggesting PHD2 to be the more dominant isoform in driving HIF-1α transient response [36, 37]. Further questions could be asked. For example, how would the turnover rate of PHD2 and PHD3 differentially affect HIF response? These simulations could be readily performed as shown in Fig. 2c, e which predict that less stable PHD3 imparts a more pronounced effect on steady-state level of HIF-1α.

Transcriptional Feedback

As a transcription factor, HIF actively contributes to its own regulation. Most importantly, HIF trans-activates the PHD2 and PHD3 genes adding a direct negative feedback arm to the PHD-mediated HIF regulation [38, 39]. Despite their oxygen dependency, which prevents them from functioning under hypoxic conditions, experimental data indicate that enzymatic activity of both PHD2 and PHD3 remains detectable in hypoxic cells maintaining reactivity of the HIF system for additional hypoxic insults [39]. This feedback loop is possibly further supported by oxygen redistributed from mitochondria during the HIF-driven metabolic switch. Indeed, upon the inhibition of the mitochondrial respiration by nitric oxide, O2 redistribution was observed leading to the inactivation of HIF [40]. Thus, one can speculate that the HIF-mediated induction of the PHDs may allow setting the PHD-HIF system to a new steady state at lower pO2 levels (Fig. 2a).

A distinct type of transcriptional feedback is mediated by one of the HIF-3α isoforms termed inhibitory PAS domain protein (IPAS). IPAS is an alternative splicing product of the HIF-3α locus that lacks the region encoding the C-terminal transactivation domains of the HIF-1 and HIF-2α [41]. As such, it competes with ARNT for binding HIF-α subunits acting as a dominant negative regulator of HIFs [42]. The IPAS-specific splicing product of the HIF-3α locus is hypoxia-inducible and HIF-1 binds to the hypoxia-responsive cis-element of the IPAS promoter representing a classic negative feedback that restricts HIF-mediated gene expression in hypoxia (Fig. 2a) [41, 43]. Interestingly, however, the IPAS-specific mRNA splicing was still observed in the absence of the HIF-1-binding site of the IPAS promoter indicating that HIF-independent factors may also be involved in the production of the dominant negative isoform [43]. The uncoupled nature of IPAS expression and IPAS mRNA splicing suggest additional control mechanisms in this regulation. Indeed, since the normoxic expression of IPAS is apparently restricted to corneal epithelial cells and some neuronal elements in mice, HIF-independent control mechanisms may contribute to the tissue-specific nature of the IPAS-mediated regulation of HIF activity.

HIF-1α is not only under feedback control by hydroxylases or IPAS but an increasing body of experimental evidence shows that it is also negatively regulated by miRNAs. These include miR-210 that not only indirectly facilitates HIF activity by targeting GPD1-L but also silences MNT, a member of the MYC/MAD/MYX transcription factor family, which antagonizes the trans-activating function of MYC [44]. This enables MYC-mediated induction of genes involved in the resolution of HIF-induced cell cycle arrest as well as cellular metabolism. The latter includes PDK1 that, as mentioned above, may play a role in the metabolic inhibition of PHDs, so one can speculate that the miR-210-mediated upregulation of MYC represents a mechanism to amplify HIF activity [45]. Since MYC has also been reported to support HIF-1α directly by interfering with the VHL-dependent degradation of HIF-1α, these findings suggest the existence of MYC-mediated feedforward loops in the HIF pathway [46]. Intriguingly, however, HIF and MYC are traditionally considered to have antagonistic effects in the hypoxic cell. Indeed, HIF was found to counteract MYC by various underlying mechanisms including the induction of MXI1, another MYC antagonist, competition with MYC for promoter binding or promoting its proteasomal degradation [47, 48]. This paradox may reflect the different models studied, so the biological relevance of the miR-210-promoted MYC functions in the regulation of HIF requires further clarification. Additional targets of miR-210 including the mitochondrial iron-sulfur cluster scaffold protein or the transferrin receptor, elements of the intracellular iron homeostasis, add another level of complexity to the regulation of the HIF pathway by merging physiologic, metabolic and transcriptional feedback loops [49, 50].

Besides miR-210, the hypoxia up-regulated, HIF-inducible miR-155 also seems to be critical in the regulation of HIF. While (as we discuss later) miR-155 targets multiple elements related to the mTOR pathway adding further complexity to the interplay between HIF and other signaling pathways (Fig. 3a), it also mediates the degradation of the HIF-1α transcript itself establishing a hypoxia-responsive negative transcriptional feedback loop within the HIF pathway [51] (Fig. 2a).

Emergence of oscillation and controlling factors. a Illustrative simulations of different scenarios showing non-oscillatory dynamics, damped and sustained oscillations and their dynamic transition when the cells are switched from normoxic to hypoxic conditions. Simulations were carried out using the model given in Fig. 2. b Comparative knock-out simulations of HIF-1α time course when the negative feedback loop mediated by PHD2 and miR-155 are broken. c Sensitivity analysis showing the effect of the PHD2 feedback strength on the oscillation pattern. Parameter values used for plotting are given in the Appendix (or Supplementary Material). All species units are in nM

Do microRNAs contribute to shaping HIF dynamics?

The miRNA-mediated negative feedback loops pose the question if they have any role in shaping HIF system’s dynamics? Having different mechanistic details, miRNA-mediated feedbacks generally operate on a shorter time-scale than feedbacks induced by the PHDs and are, thus, expected to have differential roles. Nevertheless, our understanding regarding their functional redundancy remains poorly defined.

In order to examine this question, we constructed a core mathematical model of HIF regulation that accounts for the mechanistic differences between miRNA- and PHD-mediated feedbacks. For simplicity, the model considers only one feedback of each type assumed to be driven by PHD2 and miR-155 (model scheme is given in Fig. 2a and Figure S2, model description is in the SM). We calibrate the model so that it could capture the typical transient HIF-1α profile under a hypoxic insult based on previously obtained parameter values [14]. Model simulations revealed unexpected differences between the feedbacks. While altering, the PHD2-mediated feedback (by changing HIF-1 induced PHD2 transcription rate) does not really affect HIF-1α rising time (Fig. 2h), strengthening the miR-155-induced feedback, instead, accelerates the reaction of HIF-1α to hypoxia with a faster response rate and a quicker return to steady-state level (Fig. 2g). This suggests the negative feedback induced by miR-155 provides additional control to the reaction rate, duration, and amplitude of HIF-1α response to hypoxia that are not easily achieved with hydroxylase-induced feedback alone. Instead of increasing miR-155 transcriptional rate, we next asked the model whether a tighter association between miR-155 and HIF-1α mRNA would affect the system’s dynamics, and if so, how? Interestingly, comparative simulations of HIF-1α dynamic response show that when miR-155 binds weakly to HIF-1α mRNA, increasing the rate of HIF-1α degradation triggered by PHD2 lowers HIF-1α steady-state level as expected (Fig. 2i). However, the opposite is predicted when miR-155 binds tightly to HIF-1α mRNA (Fig. 2j). Moreover, when we simulate the steady-state HIF-1α level fold change in response to hypoxia allowing both miR-155-HIF-1α binding rate and HIF-1α degradation rate to change, we found that HIF-1α level responds in a biphasic manner to its degradation rate at weak miR-155-HIF-1α association, while it increases monotonically with its degradation rate at strong miR-155-HIF-1α association (Fig. 2k). These predictions together imply that miR-155 does not just add another redundant feedback to HIF control but serves to fine-tune HIF signaling dynamics in an intricate and nonlinear manner. Modulating how miR-155 regulates HIF-1α transcription could significantly influence how HIF-1α responding to factors related to the hydroxylases under both normal and hypoxic conditions.

What controls HIF-1’s oscillation?

While a primary function of negative feedback regulation is to enable signal adaptation, it is well known to underlie oscillatory behaviors [52, 53]. Under concurrent control of multiple negative feedbacks, it is expected that HIF-1 may oscillate in specific cellular contexts [53]. Although it remains debatable what physiological function an oscillatory HIF-1 profile may bring, accumulating evidence suggest that oscillatory dynamics may provide a way to encode more signaling information than transient dynamics [54]. We use our simplified model to ask how oscillation may arise and what may control HIF oscillatory dynamics (see model details in Figure S3 and related SM). Exploration of the model parameter space shows that spontaneous oscillation could robustly arise in the system under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Interestingly, we observed four typical scenarios from simulations when cells are switched from equilibrium in normoxia to hypoxia as displayed in Fig. 3a. In response to hypoxia, pre-existing oscillation occurring in normoxia may be completely abolished, maintained, or changed to damped oscillation depending on the parameter regimes. In case where oscillation persists when cells are switched to hypoxia, we frequently observed change in the oscillatory pattern with lower or higher amplitude, but generally the oscillation period is preserved. While examining the role of miR-155- and PHD2-mediated feedbacks in the emergence of oscillation, model simulations of feedback knock-out predict that breaking the miR-155 feedback only mildly affects oscillation while breaking the PHD2 feedback completely eliminates oscillation (Fig. 3b). This suggests that negative feedbacks induced by the PHDs play a determining role in triggering oscillation. Moreover, varying the strength of this feedback loop could robustly modulate the amplitude of the oscillatory profile (Fig. 3c).

Crosstalk between the HIF and other regulatory pathways

The above examples demonstrate the intricate nature of the HIF regulation by various feedback loops and how these individual circuits create regulatory networks to provide contextual opportunities for the precise temporo-spatial regulation of the HIF-mediated responses. However, additional layers of complexity also exist in the form of crosstalk between HIF and other signaling pathways.

The HIF-mediated hypoxic induction of the PHDs has been hypothesized to form a link between the HIF and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway as well. In this model, elevated levels of PHDs represent an adaptive step to match the stabilized HIFs and, thus, limit the effect of the mTOR pathway on HIF-1α [55]. The involvement of mTOR in the regulation of HIF-1 was first suggested by independent studies of the oncogene-related activation of VEGF [56–60]. Although mTOR is believed to act as a hub for various signaling pathways, the PKB/AKT pathway was found to be the dominant upstream regulator of the mTOR-mediated HIF-1 activity in hypoxia [61–63]. It became also clear that mTOR enhances HIF-1 transcriptional activity without affecting its mRNA levels or degradation rate [58, 63]. Current data suggest that mTOR may up-regulate HIF-1 by multiple mechanisms possibly depending on the cell type and/or physiological context (Fig. 4a).

Intensive crosstalk between the AKT/mTOR and HIF pathways. Schematic overview of the interplay between the AKT/mTOR and HIF pathway including the positive feedback loop via LOX and a coherent feedforward loop via GSK-3β. mTOR, that can integrate various stimuli, influences the HIF-mediated cellular responses directly by adjusting the translational rate of the HIF-1α mRNA and indirectly via the modification of its transcriptional activity. In return, HIF induces a number of measures to regulate various elements of the mTOR pathway. b–e Modeling AKT/mTORC1-HIF crosstalk. b Simulated bistable dependence of HIF-1α steady-state level on increasing total AKT. T1 (T2) indicates the AKT level threshold at which the system abruptly switches up (down) to a high (low) level of HIF-1α as a consequence of bistability-induced hysteresis. c Time-course simulations showing the system could settle in either one of two stable steady states when it resides within a bistable regime. c Predicted effect of changing mTORC1 activity on bistability. e Predicted effect of changing GSK-3β abundance on bistability. Details of the model equations and values used for plotting are given in the Appendix (or Supplementary Material). All species units are in nM

mTOR is a known regulator of the translation by phosphorylating the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (eIF4E-BP1), a suppressor of the 5′ CAP-dependent translation [64]. As this has been shown to alter the protein expression pattern in hypoxic cells, the mTOR-mediated enhancement of the HIF-α translation is a widely accepted explanation for the negative effects of rapamycin on HIF-1 [65]. Indeed, down-regulation of the mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2), a redox-sensitive activator of the PKB/AKT pathway, leads to decreased abundance of the HIF-2α transcripts in the polysomal fractions (Fig. 4a) [66].

In recent years, it has become appreciated that reactive oxygen species (ROS) may also play an important role in cellular signaling pathways. A number of studies have proposed that ROS can regulate hydroxylase activity and promote stabilization of HIF [67–70]. A good example for the ROS-mediated HIF regulation is the HIF-inducible lysyl oxidase (LOX) [63]. The LOX gene encodes a copper-dependent amine oxidase that catalyzes the cross-linking of collagen and elastin in the extracellular matrix while producing hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Current data indicate that, following its HIF-dependent up-regulation in hypoxia, LOX-generated H2O2 activates the PKB/AKT-mTOR axis leading to the up-regulation of the HIF-1α translation forming another positive feedback loop between mTOR and HIF [63]. These data also raise the question of whether the mTORC2 receives and transmits the signals of the reactive oxygen species to the HIF pathway via the PKB/AKT-mTORC1 axis.

Besides the mTOR-mediated translational regulation, PKB/AKT has also been reported to be involved in the proteasomal degradation of HIF-1α [71]. This effect seems to involve the glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β)-mediated phosphorylation of HIF-1α that facilitates its binding to FBW7, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that recognizes GSK3β-phosphorylated proteins and targets them for proteasomal degradation [72]. Since the inactivating phosphorylation of GSK3β is primarily mediated by PKB/AKT, activation of the PKB/AKT pathway not only elevates the translational rate of the HIF-1α transcript via mTOR but also mimics the effect of hypoxia as it blocks proteasomal degradation of HIF-1.

mTOR has additional effects on HIF-1α that are also independent of the up-regulation of HIF-1α translation. It was found to associate with HIF-1α via the mTOR complex 1 member RAPTOR and a putative TOR motif of HIF-1α [60]. Although mTOR possesses serine/threonine kinase activity and phosphorylation of HIF-1α has been reported as well, consequences of the physical association of mTOR and HIF-1 remain to be determined [60, 73]. More recently, however, mTOR has been shown to phosphorylate MINT3, a regulator of the membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases (MT-MMPs), at its threonine 5/serine 7 residues [74]. This modification promotes MINT3 binding to and inactivating of FIH-1 [75]. By sequestering the HIF-1 suppressor FIH-1 to the Golgi membrane in cooperation with the MT1-MMP, the mTOR/MINT3/MT1-MMP axis could efficiently support the transcriptional activity of HIF-1 independently of the rate of its translation. Interestingly, in independent studies, MT1-MMP has been found to be a target gene for HIF-2 in renal cell carcinoma cells raising the question if the mTOR-regulated MINT3/MT1-MMP/FIH-1-mediated positive feedback loop is a general mechanism in the regulation of HIFs (Fig. 4a) [76].

The rapamycin-sensitive up-regulation of the HIF-1 activity has been observed in various experimental settings leading to the induction of a wide range of HIF-1 targets. Many of these target genes have been found to form feedback loops via the regulation of the hypoxia-related activity of the mTOR pathway. These include REDD1 that has been reported to activate the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 1/2 (TSC1/2) [77]. The TSC1/2 possesses GTPase-activating function that renders the mTOR activator RHEB inactive [78]. BNIP3, another known HIF-1 target, has also been reported to facilitate the accumulation of the GDP-bound form of RHEB and the consequent down-regulation of mTOR in hypoxia [79]. In addition, the HIF-1-inducible miR-155 also targets elements of the mTOR pathway including RHEB, the mTORC2 member RICTOR and the mTOR effector ribosomal protein S6KB2 [80]. Down-regulation of these targets seemingly complements the effect of REDD1 and BNIP3 and may contribute to the limitation of the mTOR activity during hypoxia, thereby forming a negative feedback loop via the mTOR and HIF pathways (Fig. 4a).

Crosstalk with ERK

Anabolic extracellular signals that activate the mTOR pathway often diverge and activate the ERK signaling cascade as well. Although the link between the ERK and HIF pathway was identified soon after the discovery of HIFs, the nature of their interplay has remained less clear. Stabilized HIF-1α has shown to be phosphorylated by p42/44 MAP kinases both under hypoxic conditions and in response to receptor-mediated ERK-activating stimuli [81–83]. The ERK-mediated phosphorylation was found to enhance the transcriptional activity of HIF-1 in various model systems, although the exact mechanism is still to be elucidated [84, 85]. Phosphorylation sites were identified within the carboxy-terminal part of HIF-1α at the 641 and 643 positions [86]. Experimental data suggest that these modifications affect the nuclear export of HIF-1 and fundamentally alter the predicted composition of HIF-1 containing nuclear complexes [87, 88]. Hence, current data suggest that the ERK-mediated up-regulation of the HIF pathway differs from the mTOR-mediated effect and primarily acts on the transactivation function of HIFs possibly complementing the mTOR-mediated effects.

Crosstalk with NF-kappaB

Although the regulation of HIF-1α is considered mostly post-translational, recent studies revealed processes that influence its transcription as well. Intriguingly, besides its role in the mTOR-mediated HIF regulation, miR-155 is one of the identified feedbacks targeting the HIF-1α mRNA indicating its pivotal role in the regulation of the HIF pathway. In addition, besides HIF responsive elements, NF-κB consensus sequences are also present in the miR-155 promoter indicating the capacity of NF-κB-mediated stimuli to influence the HIF pathway via miR-155 [51]. Indeed, although the detailed mechanism is still not fully understood, it is clear that basal NF-κB is moderately activated in hypoxia [89–91]. Experimental data suggest that the hypoxia-mediated inhibition of the PHD activity contributes to the up-regulation of the NF-κB pathway. While active, PHDs inhibit the I kappa B kinase (IKK) attenuating the dissociation of the inhibitory kappa B (IκB) from NF-κB [92, 93]. In hypoxia, the PHD-mediated blockade of IKK is resolved leading to phosphorylation of IκB followed by activation of NF-κB. This mechanism is able to potentiates NF-κB responsiveness to certain stimuli, e.g. TNF-α [92]. It is noteworthy, however, that under other cytokine-stimulated conditions (e.g. IL-1β), inhibition of the prolyl-4-hydroxylases blocks NF-κB activity suggesting a stimulus and/or cell type-specific interaction between HIF and NF-κB pathway [94]. Once active, NF-κB induces HIF-1α via evolutionary conserved consensus binding sites identified in the HIF-1α promoter [93, 95–97]. Since NF-κB activity is not sufficient for the accumulation of the HIF-1α protein in the absence of hypoxia, current data suggest that the canonical NF-κB pathway contributes to the maintenance of the HIF-1α mRNA level, a pre-requisite of the PHD-mediated post-translational regulation of the HIF system [93]. An additional, possibly tissue specific arm of the NF-κB-mediated regulation of the HIF pathway has also been identified by showing that NF-κB can rescue HIF-2α subunits from proteasomal degradation by directly trans-activating the ARNT promoter [98]. Considering the HIF-inducible properties of the prolyl-4-hydroxylases, the PHD/NF-κB/HIF axis may represent a regulatory circuit in the HIF pathway that is capable of integrating extracellular stimuli distinct from the ones mediated by the mTOR or ERK pathways (Fig. 5). This hypothesis is further supported by recent findings that HIF-1 activity contributes to the down-regulation of inflammatory stimuli-activated NF-κB pathway via kinases including IKKβ that may represent the negative feedback arm of this putative regulatory loop [99].

Interplay between the NF-κB and HIF pathways. The PHD-HIF axis can sense inflammatory stimuli and modulate both inflammatory signaling and hypoxia response via multi-level crosstalk with the NF-κB pathway. Green arrows and red connectors indicate positive (e.g. induction or activation) and negative (inactivation) effects, respectively

What are the consequences of the crosstalk between the HIF-1 and other pathways?

Although most of the experimental and modeling effort to date has been centered on the in vitro HIF response to hypoxia with the HIF pathway being the sole focus, HIF is known to have important roles in normoxia and more complex physiological conditions as well [55]. Current data on the intensive crosstalk between the HIF and other signaling pathways depict a complex regulatory system that complements hypoxia-driven feedbacks by enabling the cell to adjust the HIF-mediated response to the status of the surrounding microenvironment. Here, we demonstrate the potential benefit of modeling by investigating the crosstalk between HIF and mTOR signaling pathways using a mathematical modeling approach.

The model’s schematic diagram is given in Fig. 4a and Figure S4. Model description is presented in details in the SM. Following the experimental details reviewed in the previous sections, the model is designed to capture a positive feedback between mTORC1 and HIF-1 mediated via LOX, on one hand, and a positive feed-forward loop between AKT and HIF-1 via GSK-3β, on the other. The presence of a positive feedback loop in the interaction circuit prompts us to hypothesize that the system may display bistable switch-like behavior. Nevertheless, it is not trivial under what parameter regime bistability could arise, nor what factors may control its emergence and how one may go about in experimentally validating such hypothesis. Our model simulations show that under permissive parameter conditions, bistability can arise in the system as illustrated in Fig. 4b. Here, the steady-state level of HIF-1α is predicted to respond in a bistable fashion to increasing total AKT (and activity, not shown).

Bistability is an interesting phenomenon in which a dynamic system could switch between two distinct stable equilibrium states in response to a single given input [100]. Long known to be widespread in physics, bistable behaviors have been identified in many cellular systems which underlie key functions, particularly decision-making in cell cycle progression, cellular differentiation, and apoptosis [100]. The occurrence of bistable behavior has three different and related consequences. Firstly, there exists a range (i.e. bistable range) of input level (in this case AKT total), within which a given input could induce two different, a low and a high, expression levels of HIF-1 protein at steady state (Fig. 4c). Whether the system settles in a low or a high state is a nontrivial matter, the answer to which depends on the system’s initial condition (i.e. its previous history). However, given sufficient knowledge of the system’s initial condition (i.e. expression and activity levels of its species), such prediction could be made with accuracy using model-based analysis. The second consequence, arguably more biologically relevant in many cases, is the ability of the system to generate abrupt switch-like responses to graded change in the triggering cues, i.e. the ability to convert an analogue input to a digital output. Consequently, a graded increase in the AKT concentration (or activity) could result in a sudden surge of HIF-1α expression when AKT exceeds a threshold level. The third consequence of bistability is termed “hysteresis”, which is the dependence of the system not only on its current input, but also on the history of the input itself. Such property could be demonstrated by visually tracing the dose-dependence curve in Fig. 4b. Starting from a low level, a gradual increase of AKT will abruptly lead to a high HIF-1 level at threshold T1 following the “low” branch of the curve. On the other hand, if the system starts at the “high” branch with high HIF-1 level and gradually decreases, it will traverse the high branch and jump to the low branch at the second AKT threshold (T2), which is lower than the first. The existence of two different input thresholds that characterize the system switching between the low and high branch is the hallmark of hysteresis, providing a “memory” for the system in response to that signal.

Since mTORC1 are often hyper-activated in cancer cells, we ask whether enhanced mTORC1 activity would affect the occurrence of bistability. Model simulations of this scenario suggest that enhanced mTORC activation induces more pronounced bistable switch characterised by enlarged bistable range, while in contrast low mTORC1 activity could abolish bistable behavior (Fig. 4d). We next interrogate the role of GSK-3β. Interestingly, although without the positive feedback induced by LOX, the feedforward governed by GSK-3β alone is incapable of giving rise to bistability, the level of GSK-3β profoundly affects the occurrence and profile of the bistable switch. Higher GSK-3β promotes bistability but leads to reduced HIF-1 steady-state level as expected, while loss of GSK-3β could transform the dose response from a bistable to a sigmoidal switch (Fig. 4e).

Summary and conclusions

As we have seen previously, decades of experimental work using traditional biochemical approaches have uncovered a great deal of mechanistic understanding into hypoxia and HIF signaling. What has emerged is a complex picture that substitutes the notion of HIF pathway as a linear cascade of signal transduction with a novel network-based perspective, where complexity and non-linearity are appreciated. With this view, HIF is not merely a transducer but an integrator of multiple signals, making it a processing hub in a network of connected interactions. The ability of HIF to precisely receive, integrate and mediate signals from multiple sources to maintain homeostasis and adequately respond to extracellular perturbations is enabled by complex feedback loops and crosstalk with other signaling pathways. Such intricate control mechanisms allow the timing and amplitude of each signaling response to be fine-tuned and kept within an appropriate range. Under disease conditions, genomic and epigenetic alterations leading to aberrant protein expression or function often disrupt these regulatory mechanisms. Understanding how these complex mechanisms operate under homeostasis and how they break down in pathogenesis is of great importance. Systems biology approaches where network-based mathematical modeling is employed to manage and model complexity will be increasingly needed to obtain a systems-level understanding of the basic functioning of HIF and hypoxia signaling as well as to discover more effective therapeutic strategies with less adverse side effects.

Mathematical models provide a platform for the description, prediction and understanding of the various regulatory mechanisms in a quantitative and integrative way [100–102]. Although much has been learnt about the HIF pathway as a key sensor of hypoxia, many outstanding questions remain including, but not limited to, those exampled above. These questions are not only of interest from a basic understanding of the HIF pathway viewpoint but also could aid in our effort to target HIF signaling for therapeutic purposes. Indeed, HIF is a key regulator of metabolic homeostasis in health and in a range of disease states. Developing our understanding of the temporal and dynamic activity of this critical pathway will involve an appreciation of a systems biology approach to model the HIF pathway. This includes the integration of the canonical HIF pathway with the multiple feedback loops and levels of crosstalk which exist with other signaling networks. Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, due to the increased complexity of the system, studies aimed at providing an integrated, system-level understanding the HIF signaling remain limited. We strongly believe that systems biology approaches, where mathematical modeling is integrated with experimentation in a systematic and iterative manner, will be particularly useful to disentangle the network complexity of HIF signaling and identify governing conditions that characterize the network behavior. Deployment of models with different levels of detail enables us to flexibly zoom-in and zoom-out of the network structure which facilitates not only numerical simulations but also analytical studies. Importantly, model-based analyses and predictions are excellent ways to articulate novel hypotheses and design appropriate experiments to test them. Using this approach, we expect to develop a deep understanding of the nature of the HIF response in hypoxia and how this impacts on physiology and disease. This will be important in identifying appropriate pharmacological approaches to interfere with this pathway for therapeutic benefit.

References

Conway Morris S (2006) Darwin's dilemma: the realities of the Cambrian 'explosion'. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 361(1470):1069–1083

Semenza GL (2001) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: control of oxygen homeostasis in health and disease. Pediatr Res 49(5):614–617

Semenza GL, Nejfelt MK, Chi SM, Antonarakis SE (1991) Hypoxia-inducible nuclear factors bind to an enhancer element located 3' to the human erythropoietin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88(13):5680–5684

Talks KL, Turley H, Gatter KC, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Harris AL (2000) The expression and distribution of the hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha in normal human tissues, cancers, and tumor-associated macrophages. Am J Pathol 157(2):411–421

Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL (1995) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92(12):5510–5514

Willam C, Nicholls LG, Ratcliffe PJ, Pugh CW, Maxwell PH (2004) The prolyl hydroxylase enzymes that act as oxygen sensors regulating destruction of hypoxia-inducible factor alpha. Adv Enzyme Regul 44:75–92

Hirsila M, Koivunen P, Gunzler V, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J (2003) Characterization of the human prolyl 4-hydroxylases that modify the hypoxia-inducible factor. J Biol Chem 278(33):30772–30780

Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, von Kriegsheim A, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ et al (2001) Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 292(5516):468–472

Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER, Ratcliffe PJ (1999) The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399(6733):271–275

Lando D, Peet DJ, Whelan DA, Gorman JJ, Whitelaw ML (2002) Asparagine hydroxylation of the HIF transactivation domain a hypoxic switch. Science 295(5556):858–861

Li SH, Shin DH, Chun YS, Lee MK, Kim MS, Park JW (2008) A novel mode of action of YC-1 in HIF inhibition: stimulation of FIH-dependent p300 dissociation from HIF-1{alpha}. Mol Cancer Ther 7(12):3729–3738

McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, Claridge TD, Seibel JF, Horsfall LE, Schofield CJ (2002) Hypoxia-inducible factor asparaginyl hydroxylase (FIH-1) catalyses hydroxylation at the beta-carbon of asparagine-803. Biochem J 367(Pt 3):571–575

Cavadas MA, Nguyen LK, Cheong A (2013) Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) network: insights from mathematical models. Cell communication and signaling : CCS 11(1):42

Nguyen LK, Cavadas MA, Scholz CC, Fitzpatrick SF, Bruning U, Cummins EP, Tambuwala MM, Manresa MC, Kholodenko BN, Taylor CT et al (2013) A dynamic model of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) network. J Cell Sci 126(Pt 6):1454–1463

Kolch W, Halasz M, Granovskaya M, Kholodenko BN (2015) The dynamic control of signal transduction networks in cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer 15(9):515–527

Kholodenko BN (2006) Cell-signaling dynamics in time and space. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7(3):165–176

Semenza GL, Wang GL (1992) A nuclear factor induced by hypoxia via de novo protein synthesis binds to the human erythropoietin gene enhancer at a site required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol 12(12):5447–5454

Wang GL, Semenza GL (1993) Desferrioxamine induces erythropoietin gene expression and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 DNA-binding activity: implications for models of hypoxia signal transduction. Blood 82(12):3610–3615

Ravasi G, Pelucchi S, Greni F, Mariani R, Giuliano A, Parati G, Silvestri L, Piperno A (2014) Circulating factors are involved in hypoxia-induced hepcidin suppression. Blood Cells Mol Dis 53(4):204–210

Mastrogiannaki M, Matak P, Mathieu JR, Delga S, Mayeux P, Vaulont S, Peyssonnaux C (2012) Hepatic hypoxia-inducible factor-2 down-regulates hepcidin expression in mice through an erythropoietin-mediated increase in erythropoiesis. Haematologica 97(6):827–834

Hintze KJ, McClung JP (2011) Hepcidin: a critical regulator of iron metabolism during hypoxia. Adv Hematol 2011:510304

Leung PS, Srai SK, Mascarenhas M, Churchill LJ, Debnam ES (2005) Increased duodenal iron uptake and transfer in a rat model of chronic hypoxia is accompanied by reduced hepcidin expression. Gut 54(10):1391–1395

McNeill LA, Flashman E, Buck MR, Hewitson KS, Clifton IJ, Jeschke G, Claridge TD, Ehrismann D, Oldham NJ, Schofield CJ (2005) Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase 2 has a high affinity for ferrous iron and 2-oxoglutarate. Mol Biosyst 1(4):321–324

Shweiki D, Itin A, Soffer D, Keshet E (1992) Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature 359(6398):843–845

Takeda N, Maemura K, Imai Y, Harada T, Kawanami D, Nojiri T, Manabe I, Nagai R (2004) Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 gene promotes angiogenesis through the transactivation of both vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, Flt-1. Circ Res 95(2):146–153

Benita Y, Kikuchi H, Smith AD, Zhang MQ, Chung DC, Xavier RJ (2009) An integrative genomics approach identifies Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1)-target genes that form the core response to hypoxia. Nucleic Acids Res 37(14):4587–4602

Linn TC, Pettit FH, Reed LJ (1969) Alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complexes. X. Regulation of the activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex from beef kidney mitochondria by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 62(1):234–241

Seifert F, Ciszak E, Korotchkina L, Golbik R, Spinka M, Dominiak P, Sidhu S, Brauer J, Patel MS, Tittmann K (2007) Phosphorylation of serine 264 impedes active site accessibility in the E1 component of the human pyruvate dehydrogenase multienzyme complex. Biochemistry 46(21):6277–6287

Pan Y, Mansfield KD, Bertozzi CC, Rudenko V, Chan DA, Giaccia AJ, Simon MC (2007) Multiple factors affecting cellular redox status and energy metabolism modulate hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase activity in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell Biol 27(3):912–925

Selak MA, Armour SM, MacKenzie ED, Boulahbel H, Watson DG, Mansfield KD, Pan Y, Simon MC, Thompson CB, Gottlieb E (2005) Succinate links TCA cycle dysfunction to oncogenesis by inhibiting HIF-alpha prolyl hydroxylase. Cancer Cell 7(1):77–85

Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, Palsson-McDermott EM, McGettrick AF, Goel G, Frezza C, Bernard NJ, Kelly B, Foley NH et al (2013) Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1beta through HIF-1alpha. Nature 496(7444):238–242

Mracek T, Drahota Z, Houstek J (2013) The function and the role of the mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in mammalian tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta 1827(3):401–410

Kelly TJ, Souza AL, Clish CB, Puigserver P (2011) A hypoxia-induced positive feedback loop promotes hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha stability through miR-210 suppression of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1-like. Mol Cell Biol 31(13):2696–2706

Tanaka H, Sasayama T, Tanaka K, Nakamizo S, Nishihara M, Mizukawa K, Kohta M, Koyama J, Miyake S, Taniguchi M et al (2013) MicroRNA-183 upregulates HIF-1alpha by targeting isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2) in glioma cells. J Neurooncol 111(3):273–283

Giannakakis A, Sandaltzopoulos R, Greshock J, Liang S, Huang J, Hasegawa K, Li C, O'Brien-Jenkins A, Katsaros D, Weber BL et al (2008) miR-210 links hypoxia with cell cycle regulation and is deleted in human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 7(2):255–264

Bagnall J, Leedale J, Taylor SE, Spiller DG, White MR, Sharkey KJ, Bearon RN, See V (2014) Tight control of hypoxia-inducible factor-alpha transient dynamics is essential for cell survival in hypoxia. J Biol Chem 289(9):5549–5564

Berra E, Benizri E, Ginouves A, Volmat V, Roux D, Pouyssegur J (2003) HIF prolyl-hydroxylase 2 is the key oxygen sensor setting low steady-state levels of HIF-1alpha in normoxia. EMBO J 22(16):4082–4090

Marxsen JH, Stengel P, Doege K, Heikkinen P, Jokilehto T, Wagner T, Jelkmann W, Jaakkola P, Metzen E (2004) Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) promotes its degradation by induction of HIF-alpha-prolyl-4-hydroxylases. Biochem J 381(Pt 3):761–767

Stiehl DP, Wirthner R, Koditz J, Spielmann P, Camenisch G, Wenger RH (2006) Increased prolyl 4-hydroxylase domain proteins compensate for decreased oxygen levels. Evidence for an autoregulatory oxygen-sensing system. J Biol Chem 281(33):23482–23491

Hagen T, Taylor CT, Lam F, Moncada S (2003) Redistribution of intracellular oxygen in hypoxia by nitric oxide: effect on HIF1alpha. Science 302(5652):1975–1978

Makino Y, Kanopka A, Wilson WJ, Tanaka H, Poellinger L (2002) Inhibitory PAS domain protein (IPAS) is a hypoxia-inducible splicing variant of the hypoxia-inducible factor-3alpha locus. J Biol Chem 277(36):32405–32408

Makino Y, Cao R, Svensson K, Bertilsson G, Asman M, Tanaka H, Cao Y, Berkenstam A, Poellinger L (2001) Inhibitory PAS domain protein is a negative regulator of hypoxia-inducible gene expression. Nature 414(6863):550–554

Makino Y, Uenishi R, Okamoto K, Isoe T, Hosono O, Tanaka H, Kanopka A, Poellinger L, Haneda M, Morimoto C (2007) Transcriptional up-regulation of inhibitory PAS domain protein gene expression by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1): a negative feedback regulatory circuit in HIF-1-mediated signaling in hypoxic cells. J Biol Chem 282(19):14073–14082

Zhang Z, Sun H, Dai H, Walsh RM, Imakura M, Schelter J, Burchard J, Dai X, Chang AN, Diaz RL et al (2009) MicroRNA miR-210 modulates cellular response to hypoxia through the MYC antagonist MNT. Cell Cycle 8(17):2756–2768

Kim JW, Gao P, Liu YC, Semenza GL, Dang CV (2007) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and dysregulated c-Myc cooperatively induce vascular endothelial growth factor and metabolic switches hexokinase 2 and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1. Mol Cell Biol 27(21):7381–7393

Doe MR, Ascano JM, Kaur M, Cole MD (2012) Myc posttranscriptionally induces HIF1 protein and target gene expression in normal and cancer cells. Cancer Res 72(4):949–957

Zhang H, Gao P, Fukuda R, Kumar G, Krishnamachary B, Zeller KI, Dang CV, Semenza GL (2007) HIF-1 inhibits mitochondrial biogenesis and cellular respiration in VHL-deficient renal cell carcinoma by repression of C-MYC activity. Cancer Cell 11(5):407–420

Koshiji M, Kageyama Y, Pete EA, Horikawa I, Barrett JC, Huang LE (2004) HIF-1alpha induces cell cycle arrest by functionally counteracting Myc. EMBO J 23(9):1949–1956

Yoshioka Y, Kosaka N, Ochiya T, Kato T (2012) Micromanaging iron homeostasis: hypoxia-inducible micro-RNA-210 suppresses iron homeostasis-related proteins. J Biol Chem 287(41):34110–34119

Wang H, Flach H, Onizawa M, Wei L, McManus MT, Weiss A (2014) Negative regulation of Hif1a expression and TH17 differentiation by the hypoxia-regulated microRNA miR-210. Nat Immunol 15(4):393–401

Bruning U, Cerone L, Neufeld Z, Fitzpatrick SF, Cheong A, Scholz CC, Simpson DA, Leonard MO, Tambuwala MM, Cummins EP et al (2011) MicroRNA-155 promotes resolution of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha activity during prolonged hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol 31(19):4087–4096

Kholodenko BN (2000) Negative feedback and ultrasensitivity can bring about oscillations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. Eur J Biochem / FEBS 267(6):1583–1588

Nguyen LK (2012) Regulation of oscillation dynamics in biochemical systems with dual negative feedback loops. J R Soc Interface / the Royal Society 9(73):1998–2010

Purvis JE, Lahav G (2013) Encoding and decoding cellular information through signaling dynamics. Cell 152(5):945–956

Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV (2011) The purpose of the HIF-1/PHD feedback loop: to limit mTOR-induced HIF-1alpha. Cell Cycle 10(10):1557–1562

Mayerhofer M, Valent P, Sperr WR, Griffin JD, Sillaber C (2002) BCR/ABL induces expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its transcriptional activator, hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha, through a pathway involving phosphoinositide 3-kinase and the mammalian target of rapamycin. Blood 100(10):3767–3775

Hudson CC, Liu M, Chiang GG, Otterness DM, Loomis DC, Kaper F, Giaccia AJ, Abraham RT (2002) Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression and function by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Mol Cell Biol 22(20):7004–7014

Treins C, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Murdaca J, Semenza GL, Van Obberghen E (2002) Insulin stimulates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/target of rapamycin-dependent signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 277(31):27975–27981

Humar R, Kiefer FN, Berns H, Resink TJ, Battegay EJ (2002) Hypoxia enhances vascular cell proliferation and angiogenesis in vitro via rapamycin (mTOR)-dependent signaling. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 16(8):771–780

Land SC, Tee AR (2007) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha is regulated by the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) via an mTOR signaling motif. J Biol Chem 282(28):20534–20543

Gao N, Ding M, Zheng JZ, Zhang Z, Leonard SS, Liu KJ, Shi X, Jiang BH (2002) Vanadate-induced expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway and reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem 277(35):31963–31971

Dayan F, Bilton RL, Laferriere J, Trottier E, Roux D, Pouyssegur J, Mazure NM (2009) Activation of HIF-1alpha in exponentially growing cells via hypoxic stimulation is independent of the AKT/mTOR pathway. J Cell Physiol 218(1):167–174

Pez F, Dayan F, Durivault J, Kaniewski B, Aimond G, Le Provost GS, Deux B, Clezardin P, Sommer P, Pouyssegur J et al (2011) The HIF-1-inducible lysyl oxidase activates HIF-1 via the AKT pathway in a positive regulation loop and synergizes with HIF-1 in promoting tumor cell growth. Cancer Res 71(5):1647–1657

Heesom KJ, Denton RM (1999) Dissociation of the eukaryotic initiation factor-4E/4E-BP1 complex involves phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 by an mTOR-associated kinase. FEBS Lett 457(3):489–493

Magagnin MG, van den Beucken T, Sergeant K, Lambin P, Koritzinsky M, Devreese B, Wouters BG (2008) The mTOR target 4E-BP1 contributes to differential protein expression during normoxia and hypoxia through changes in mRNA translation efficiency. Proteomics 8(5):1019–1028

Nayak BK, Feliers D, Sudarshan S, Friedrichs WE, Day RT, New DD, Fitzgerald JP, Eid A, Denapoli T, Parekh DJ et al (2013) Stabilization of HIF-2alpha through redox regulation of mTORC2 activation and initiation of mRNA translation. Oncogene 32(26):3147–3155

Moon EJ, Sonveaux P, Porporato PE, Danhier P, Gallez B, Batinic-Haberle I, Nien YC, Schroeder T, Dewhirst MW (2010) NADPH oxidase-mediated reactive oxygen species production activates hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) via the ERK pathway after hyperthermia treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(47):20477–20482

Bonello S, Zahringer C, BelAiba RS, Djordjevic T, Hess J, Michiels C, Kietzmann T, Gorlach A (2007) Reactive oxygen species activate the HIF-1alpha promoter via a functional NFkappaB site. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27(4):755–761

Simon MC (2006) Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species are required for hypoxic HIF alpha stabilization. Adv Exp Med Biol 588:165–170

Schroedl C, McClintock DS, Budinger GR, Chandel NS (2002) Hypoxic but not anoxic stabilization of HIF-1alpha requires mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 283(5):L922–L931

Cassavaugh JM, Hale SA, Wellman TL, Howe AK, Wong C, Lounsbury KM (2011) Negative regulation of HIF-1alpha by an FBW7-mediated degradation pathway during hypoxia. J Cell Biochem 112(12):3882–3890

Welcker M, Clurman BE (2008) FBW7 ubiquitin ligase: a tumour suppressor at the crossroads of cell division, growth and differentiation. Nat Rev Cancer 8(2):83–93

Brown EJ, Beal PA, Keith CT, Chen J, Shin TB, Schreiber SL (1995) Control of p70 s6 kinase by kinase activity of FRAP in vivo. Nature 377(6548):441–446

Sakamoto T, Weng JS, Hara T, Yoshino S, Kozuka-Hata H, Oyama M, Seiki M (2014) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 regulation through cross talk between mTOR and MT1-MMP. Mol Cell Biol 34(1):30–42

Lando D, Peet DJ, Gorman JJ, Whelan DA, Whitelaw ML, Bruick RK (2002) FIH-1 is an asparaginyl hydroxylase enzyme that regulates the transcriptional activity of hypoxia-inducible factor. Genes Dev 16(12):1466–1471

Petrella BL, Lohi J, Brinckerhoff CE (2005) Identification of membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase as a target of hypoxia-inducible factor-2 alpha in von Hippel-Lindau renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene 24(6):1043–1052

Brugarolas J, Lei K, Hurley RL, Manning BD, Reiling JH, Hafen E, Witters LA, Ellisen LW, Kaelin WG Jr (2004) Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev 18(23):2893–2904

Inoki K, Li Y, Xu T, Guan KL (2003) Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev 17(15):1829–1834

Li Y, Wang Y, Kim E, Beemiller P, Wang CY, Swanson J, You M, Guan KL (2007) Bnip3 mediates the hypoxia-induced inhibition on mammalian target of rapamycin by interacting with Rheb. J Biol Chem 282(49):35803–35813

Wan G, Xie W, Liu Z, Xu W, Lao Y, Huang N, Cui K, Liao M, He J, Jiang Y et al (2014) Hypoxia-induced MIR155 is a potent autophagy inducer by targeting multiple players in the MTOR pathway. Autophagy 10(1):70–79

Richard DE, Berra E, Gothie E, Roux D, Pouyssegur J (1999) p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinases phosphorylate hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) and enhance the transcriptional activity of HIF-1. J Biol Chem 274(46):32631–32637

Minet E, Arnould T, Michel G, Roland I, Mottet D, Raes M, Remacle J, Michiels C (2000) ERK activation upon hypoxia: involvement in HIF-1 activation. FEBS Lett 468(1):53–58

Sodhi A, Montaner S, Patel V, Zohar M, Bais C, Mesri EA, Gutkind JS (2000) The Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus G protein-coupled receptor up-regulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression and secretion through mitogen-activated protein kinase and p38 pathways acting on hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Cancer Res 60(17):4873–4880

Shi YH, Wang YX, Bingle L, Gong LH, Heng WJ, Li Y, Fang WG (2005) In vitro study of HIF-1 activation and VEGF release by bFGF in the T47D breast cancer cell line under normoxic conditions: involvement of PI-3K/AKT and MEK1/ERK pathways. J Pathol 205(4):530–536

Dimova EY, Kietzmann T (2006) The MAPK pathway and HIF-1 are involved in the induction of the human PAI-1 gene expression by insulin in the human hepatoma cell line HepG2. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1090:355–367

Mylonis I, Chachami G, Samiotaki M, Panayotou G, Paraskeva E, Kalousi A, Georgatsou E, Bonanou S, Simos G (2006) Identification of MAPK phosphorylation sites and their role in the localization and activity of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. J Biol Chem 281(44):33095–33106

Mylonis I, Chachami G, Paraskeva E, Simos G (2008) Atypical CRM1-dependent nuclear export signal mediates regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha by MAPK. J Biol Chem 283(41):27620–27627

Fabian Z, Ramadurai S, Shaw G, Nasheuer HP, Kolch W, Taylor C, Barry F (2014) Basic fibroblast growth factor modifies the hypoxic response of human bone marrow stromal cells by ERK-mediated enhancement of HIF-1alpha activity. Stem Cell Res 12(3):646–658

Oliver KM, Garvey JF, Ng CT, Veale DJ, Fearon U, Cummins EP, Taylor CT (2009) Hypoxia activates NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression through the canonical signaling pathway. Antioxid Redox Signal 11(9):2057–2064

Schmedtje JF Jr, Ji YS, Liu WL, DuBois RN, Runge MS (1997) Hypoxia induces cyclooxygenase-2 via the NF-kappaB p65 transcription factor in human vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 272(1):601–608

Figueroa YG, Chan AK, Ibrahim R, Tang Y, Burow ME, Alam J, Scandurro AB, Beckman BS (2002) NF-kappaB plays a key role in hypoxia-inducible factor-1-regulated erythropoietin gene expression. Exp Hematol 30(12):1419–1427

Cummins EP, Berra E, Comerford KM, Ginouves A, Fitzgerald KT, Seeballuck F, Godson C, Nielsen JE, Moynagh P, Pouyssegur J et al (2006) Prolyl hydroxylase-1 negatively regulates IkappaB kinase-beta, giving insight into hypoxia-induced NFkappaB activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103(48):18154–18159

Rius J, Guma M, Schachtrup C, Akassoglou K, Zinkernagel AS, Nizet V, Johnson RS, Haddad GG, Karin M (2008) NF-kappaB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1alpha. Nature 453(7196):807–811

Scholz CC, Cavadas MA, Tambuwala MM, Hams E, Rodriguez J, von Kriegsheim A, Cotter P, Bruning U, Fallon PG, Cheong A et al (2013) Regulation of IL-1beta-induced NF-kappaB by hydroxylases links key hypoxic and inflammatory signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110(46):18490–18495

Minet E, Ernest I, Michel G, Roland I, Remacle J, Raes M, Michiels C (1999) HIF1A gene transcription is dependent on a core promoter sequence encompassing activating and inhibiting sequences located upstream from the transcription initiation site and cis elements located within the 5'UTR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 261(2):534–540

van Uden P, Kenneth NS, Rocha S (2008) Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha by NF-kappaB. Biochem J 412(3):477–484

Fitzpatrick SF, Tambuwala MM, Bruning U, Schaible B, Scholz CC, Byrne A, O'Connor A, Gallagher WM, Lenihan CR, Garvey JF et al (2011) An intact canonical NF-kappaB pathway is required for inflammatory gene expression in response to hypoxia. J Immunol 186(2):1091–1096

van Uden P, Kenneth NS, Webster R, Muller HA, Mudie S, Rocha S (2011) Evolutionary conserved regulation of HIF-1beta by NF-kappaB. PLoS Genet 7(1), e1001285. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001285

Bandarra D, Biddlestone J, Mudie S, Muller HA, Rocha S (2015) HIF-1alpha restricts NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression to control innate immunity signals. Dis Model Mech 8(2):169–181

Kholodenko BN (2006) Cell-signaling dynamics in time and space. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 7(3):165–176

Nguyen LK, Kolch W, Kholodenko BN (2013) When ubiquitination meets phosphorylation: a systems biology perspective of EGFR/MAPK signaling. Cell communication and signaling : CCS 11:52

Nguyen LK, Matallanas DG, Romano D, Kholodenko BN, Kolch W (2015) Competing to coordinate cell fate decisions: the MST2-Raf-1 signaling device. Cell Cycle 14(2):189–199

Acknowledgements

The authors are funded by a grant from Science Foundation Ireland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests related to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 716 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fábián, Z., Taylor, C.T. & Nguyen, L.K. Understanding complexity in the HIF signaling pathway using systems biology and mathematical modeling. J Mol Med 94, 377–390 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-016-1383-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-016-1383-6