Abstract

Purpose

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) enables radiation oncologists to optimally spare organs at risk while achieving homogeneous dose distribution in the target volume. Despite great advances in technology, xerostomia is one of the most detrimental long-term side effects after multimodal therapy in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer (HNC). This prospective observational study examines the effect of parotid sparing on quality of life in long-term survivors.

Patients and methods

A total of 138 patients were grouped into unilateral (n = 75) and bilateral (n = 63) parotid sparing IMRT and questioned at 3, 24, and 60-month follow-up using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 and QLQ-H&N35 questionnaires. Treatment-related toxicity was scored according to the RTOG/EORTC toxicity criteria. Patients’ QoL 24 and 60 months after IMRT was analyzed by ANCOVA using baseline QoL (3 months after IMRT) as a covariate.

Results

Patients with bilateral and unilateral parotid-sparing IMRT surviving 60 months experience similar acute and late side effects and similar changes in QoL. Three months after IMRT, physical and emotional function as well as fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, and financial problems are below (function scales) or above (symptom scales) the threshold of clinical importance. In both groups, symptom burden (EORTC H&N35) is high independent of parotid sparing 3 months after IMRT and decreases over time in a similar pattern. Pain and financial function remain burdensome throughout.

Conclusion

Long-term HNC survivors show a similar treatment-related toxicity profile independent of unilateral vs. bilateral parotid-sparing IMRT. Sparing one or both parotids had no effect on global QoL nor on the magnitude of changes in function and symptom scales over the observation period of 60 months. The financial impact of the disease and its detrimental effect on long-term QoL pose an additional risk to unmet needs in this special patient population. These results suggest that long-term survivors need and most likely will benefit from early medical intervention and support within survivorship programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Radiation therapy, with or without concurrent systemic therapy, is an integral part of modern multimodal therapy for patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer (LAHNC) [1]. It is well known that radio(chemo)therapy, R(C)T, can induce severe acute and late side adverse effects in normal tissues surrounding the target volume, such as mucositis, dysphagia, xerostomia, pain, dysgeusia, and muscular fibrosis. Reducing acute and late radiation-induced toxicity has become a goal in advancing radiation therapy technology. Compared to 3D-conformal radiation (3D-CRT), the introduction of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) has resulted in reduced treatment-related toxicity and improved quality of life (QoL) in head and neck cancer (HNC) patients [2,3,4,5]. The detrimental effect of treatment on QoL in patients with LAHNC is often due to xerostomia [6, 7]. During the radiation treatment planning process, sparing of critical structures, such as swallowing muscles [8], oral mucosa with its minor salivary glands, and submandibular and parotid glands, should be prioritized outside the target volume without compromising curative dose distribution [9, 10]. To maintain parotid gland function, a mean dose of ≤26 Gy given with conventional fractionation has been generally accepted [11, 12]. It has been postulated that with conventional fractionation, acute effects have a high α/β ratio and late damage (dependent on stem cell recovery) has a low α/β ratio [13,14,15]. Furthermore, it has been shown that sparing of both parotid glands results in less observer-rated toxicity compared to only unilateral gland sparing [10, 16]. Reduced salivary function can result in severe chronic morbidity, such as dysphagia, aspiration, long-term feeding tube dependence, and dental decay [10, 17]. There are data reporting that physician-rated toxicity is consistently lower than patient reported symptoms [18, 19]. It is unclear whether comprehensive bilateral parotid sparing IMRT translates into a better patient-reported long-term QoL compared to patients in whom only one parotid gland could be spared.

Therefore, the purpose of the study was twofold: 1) to assess whether bilateral parotid sparing results in less acute and late physician-rated toxicity compared to only unilateral sparing and 2) to investigate whether bilateral parotid-sparing IMRT results in improved long-term QoL compared to patients with only unilateral parotid-sparing treatment.

Patients and methods

Study design

Before R(C)T, the radiation oncologist enrolled eligible patients into a prospective observational study. Eligible patients with LAHNC had to have M0 disease, squamous cell histology, no contraindication to R(C)T, be able to complete the QoL questionnaires, and be compliant to follow-up appointments. QoL was measured at the end of IMRT and at 3, 12, 24, and 60 months of follow-up. Questionnaires were self-completed in the physician’s office at the time of the follow-up visit.

IMRT dose prescription followed the recommendations of the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurement (ICRU) report 83 [16]. In summary, 50% of the planning target volume (PTV, D50%) received the prescribed dose (98% of the PTV received 95% of the prescription dose, D98%). Radiation-sensitive structures were contoured, and a margin of 2 mm was applied. Depending on tumor site and nodal disease, the dose constraints applied to the parotid glands and oral cavity/pharyngeal structures/larynx were ≤20 Gy and ≤30–36 Gy (mean dose), respectively. In the primary setting, a total dose of 70 Gy was given, with five fractions per week at 2 Gy per fraction [20,21,22]. In the adjuvant setting, patients received a total dose of 60–66 Gy at 2 Gy per fraction and, if indicated, risk-adapted concurrent RCT was applied with cisplatin weekly with 30 mg/m2 or 100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks.

This study focuses on long-term late effects of radiation treatment depending on gland sparing and analyzes follow-up measurements at 3, 24, and 60 months after completion of radiation treatment. Since QoL and late effects may be associated with acute side effects of R(C)T, measurements 3 months after the end of radiation treatment were included as covariates in the analyses [23].

Sampling

Twenty-four months after radiation treatment, 162 patients had completed the QoL questionnaires at the 24-month follow-up; 24 patients had to be excluded because they underwent one-sided parotidectomy during their surgery. Thus, the sample size analyzed at the measurement timepoint 24 months after radiation treatment consisted of n = 138 patients.

At the 60-month follow-up, 72 patients had completed the QoL questionnaires; 12 cases had to be excluded due to lack of information on gland sparing (n = 7) or because gland sparing was not feasible (n = 5), and 1 patient due to not participating in the 24-month measurement. Thus, the sample size analyzed at the measurement point 60 months after radiation treatment consisted of n = 59 patients. Approval was obtained from the local ethics committee. All patients provided written informed consent.

Measurements

Sociodemographic and medical variables

Patients completed self-report questionnaires on their age, sex, marital status, education level, occupation, and monthly household net income. Disease and treatment-related variables (tumor diagnosis, tumor and nodal classification, body mass index [BMI], Karnofsky Performance Status [KPS], pretreatment hemoglobin level, previous therapy, gland sparing, etc.) were documented by the senior radiation oncologist who also recorded acute and late radiation toxicity according to RTOG/EORTC (Radiation Therapy and Oncology Group/ European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer) toxicity criteria at each follow-up visit [23,24,25,26]. Routine human papillomavirus (HPV) testing was not conducted during the study period.

Quality of life

General cancer-related quality of life (QoL) was assessed with the German version of the EORTC QoL Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) [27]. The questionnaire includes 30 items which are the basis for the global quality of life scale, five function scales (emotional, physical, cognitive, social, and role functioning), and nine symptom scales of cancer-related symptoms (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, financial difficulties). In addition to the core module, the EORTC Head and Neck Module H&N35 was applied to assess cancer-related QoL specific to head and neck cancer patients [28]. The module consists of 35 items, from which 13 multi- or single-item symptom scales can be calculated (pain, swallowing, senses, speech, social eating, social contact, sexuality, problems with teeth, problems opening mouth, dry mouth, sticky saliva, coughing, felt ill). Further, the questionnaire includes five yes/no items (use of painkillers, nutritional supplements, feeding tube, weight loss, and weight gain).

Both the core questionnaire and the head and neck module were scored and calculated in accordance with the EORTC scoring manual [29]. Function and symptom scales are calculated to result in a possible scale range from 0 to 100 in each scale, with higher scores indicating better functioning or higher symptom burden, respectively. A score difference of 10 or more points is generally considered to be clinically relevant [30]. Recently, thresholds for clinical importance to improve interpretation of EORTC QLQ-C30 scores in clinical practice and research have been suggested [31]. Both EORTC QLQ-C30 and H&N35 have been shown to be valid and reliable QoL measurement instruments in patients with head and neck cancer [32,33,34].

Data analyses

All data were analyzed using SPSS (for Windows) version 20.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY, USA). Missing data in the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and H&N35 module questionnaires were treated as determined by the EORTC scoring manual. Descriptive analyses were performed to examine sociodemographic and medical characteristics of the sample. Patients with unilateral vs. bilateral parotid gland sparing were compared using t‑test for metric variables and chi-square for categorical variables.

For the comparison of general cancer-related QoL and head and neck cancer-specific QoL in patients with unilateral vs. bilateral parotid gland-sparing IMRT 24 and 60 months after radiation treatment, univariate analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were conducted for all function and symptom scales using baseline QoL (3 months after radiation treatment) as a covariate. As the effect size in relation to the comparisons of means between groups, we calculated partial eta-squared. Effect sizes are categorized as small (partial eta2 = 0.01), medium (partial eta2 = 0.06), and large (partial eta2 = 0.14), as suggested by Cohen [35].

Nonresponder analysis at 60 months after radiation treatment

Out of the 138 patients who completed the measurement 24 months after the end of radiation treatment, 63 were still alive at 60 months after the end of radiation treatment (59 of those had answered the QoL questionnaire at both measurements), 18 had died between these measurements, 1 patient was alive but had changed clinics and attended follow-up care elsewhere, and 56 were lost to follow-up. In order to assess differences between responders and non-responders at the late measurement (60 months after end of radiation treatment), those who attended the measurement 24 months after radiation treatment but did not attend the measurement 60 months after radiation treatment (n = 79) were compared with regard to sociodemographic and medical variables with those who attended both measurements (n = 59). Those who did not participate in the measurement 60 months after the end of radiation treatment (n = 79) had a higher tumor stage at diagnosis (UICC III/IV: 55% vs. 36% in those that did attend both measurements, p = 0.021), had undergone surgery significantly less often (62% vs. 80%, p = 0.026), and were retired significantly more often (49% vs. 40%, p = 0.045). In all other medical or sociodemographic variables, the samples did not differ (Supplemental data Table 1).

Results

Patients

Out of 138 patients participating in the measurement 24 months after radiation treatment, 75 (54%) had received unilateral parotid gland-sparing IMRT and 63 (46%) had received bilateral parotid gland-sparing treatment. The majority of the sample was male (70%) and the median age at inclusion in the study was 61 years. Those who had received unilateral parotid gland-sparing radiation treatment differed from those who had received bilateral parotid gland-sparing radiation treatment with regard to tumor site: patients with unilateral parotid gland sparing had more often been diagnosed with tumors of the oral cavity (36%) or the oropharynx (49.3%), while those with bilateral parotid gland sparing were more often diagnosed with tumors of the hypopharynx or larynx (38.1%; p < 0.001). Further, patients with unilateral parotid gland sparing had more often been diagnosed with a higher nodal classification (68% vs. 44% with N2/3, p = 0.005), had more often undergone surgery (79% vs. 59%, p = 0.011), and had a lower pre-treatment hemoglobin level (11.7 vs. 12.3, p = 0.037). Samples did not differ with regard to tumor classification, alcohol or nicotine consumption, or with regard to age, sex, marital status, or any other sociodemographic variable (Table 1).

Quality of life and physician-rated side effects

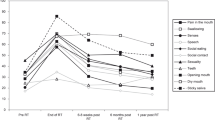

In the patient group with unilateral parotid sparing, IMRT descriptive analyses on the course of quality of life scores (EORTC QLQ-C30) from 3 months to 24 and to 60 months after R(C)T revealed that QoL at the end of the acute toxicity phase (3 months) with regard to the physical and emotional function scales as well the symptoms fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, and financial problems reached the thresholds of clinical importance (TCI), as recently suggested by Giesinger and colleagues [31]. At 24 months, physical and emotional function remained below the threshold of clinical importance (TCI; low function scales = bad/worse), and pain, dyspnea, and financial problems above the TCI (high symptom scales = bad/worse). At the 60-month measuring timepoint, all function scales improved and scored above the TCI (good/better); only the symptom scales dyspnea and financial problems were above the TCI (Supplemental data, panel 1).

In the group with bilateral parotid-sparing IMRT 3 months after treatment, the function scales physical, role, and emotional function reached the TCI and physical and emotional function remained below the TCI throughout the observation period. The symptom scales fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, and financial problems scored above the TCI 3 months after completion of treatment. For both groups, only dyspnea and financial problems continued to be above the TCI until 60 months after R(C)T (Table 2, Supplemental data, panel 1).

With regard to head and neck cancer-specific quality of life (EORTC QLQ-H&N35), mean scores in both groups decreased from 3 months to 24 months after radiation in nearly all symptom subscales by a clinically relevant degree (by more than 10 points: pain, swallowing, senses, social eating), except the teeth symptom scale, where mean scores increased by 12.9 points (unilateral) and by 12 points (bilateral). For the subscale dry mouth, the symptom score decreased in the group with unilateral gland sparing by 9.4 points compared to the group with bilateral gland-sparing treatment by 22 points (Table 2, Supplemental data, panel 2).

From 24 months to 60 months after the end of radiation, mean scores in most scales did not change at a clinically significant level (5–10 points for a “little” change) as defined by Osoba and colleagues [36], except for sexuality (plus 9.6 points), opening mouth (plus 6.6 points), and cough (plus 8.7 points) in the bilateral gland-sparing group, and teeth (plus 8.4 points) and cough (plus 5.5 points) in the unilateral gland-sparing group (Table 2, Supplemental data, panel 2).

Except for the subscale “dry mouth,” where patients with unilateral gland sparing reported higher symptom burden than those with bilateral gland sparing (mean values 58.6 vs. 45.2, pANCOVA = 0.018) 24 months after R(C)T, none of the mean differences between the two groups reached statistical significance at 24 or 60 months after R(C)T (Table 3). This finding did not correspond to the physician-rated side effects 24 months after the end of radiation treatment, where physicians did not find any difference with regard to xerostomia between the two groups and considered 59% of the patients in both groups to not have any xerostomia. In none of the physician-rated acute and late side effects was any difference found between bilateral vs. unilateral parotid gland sparing during the observation period, except for the mucositis rating 3 months after R(C)T, where physicians rated symptoms lower for patients with bilateral gland sparing (Table 4).

Discussion

The purpose of the study was 1) to describe physician-rated long-term radiation-induced toxicity in patients with LAHNC depending on bilateral vs. unilateral parotid gland-sparing RT and 2) to investigate whether bilateral parotid-sparing IMRT translates into a better patient-reported QoL outcome compared to patients who had unilateral parotid sparing.

HNC patients share many of the challenges of survivorship with other cancer survivors, including the risk of recurrence, second primary tumors, and late treatment-related toxicity and functional deficits [37,38,39,40].

The patient cohort of this study represents in its characteristics the general HNC patient population with its median age of 61 years with a male predominance of 70% [41].

Xerostomia is an important acute and late side effect affecting daily life after R(C)T in HNC patients [7]. Studies have shown that QoL is adversely affected by xerostomia [5, 42,43,44]. Conversely, others did not observe a correlation between QoL and xerostomia [45].

Approximately 20 years ago, when IMRT became widely available, many groups showed that parotid glands can be spared without compromising dose distribution and local control rates. Contrary to these results, it has been reported that sparing both parotid glands results in less observer-rated toxicity [10, 46, 47]. In a previous subgroup analysis of the present study, it was shown that with a median follow-up of approximately 1 year, bilateral parotid sparing did result in less xerostomia and dysphagia as well as a decreased dependency on gastrostomy feeding tubes [10]. With longer follow-up, this observation seems to be no longer reproducible. In the present patient population with a follow-up of 60 months after the end of radiation, there was no difference in physician-rated or patient-reported dysphagia or xerostomia in the acute or late toxicity phase. The only relevant difference observed at the end of the acute toxicity phase was seen in the rate of physician-rated mucositis, with more patients in the group of unilateral parotid gland sparing having grade 1 and 2 mucositis at the first follow-up 3 months after completion of R(C)T, which did not have an impact on QoL. Nearly half of the patients with unilateral gland sparing had grade 1 and 2 oral mucositis, which is in agreement with reports where nearly all patients have oral mucositis early after IMRT, independent of the RT technique or concomitant chemotherapy, with a strong drop in QoL [48]. In agreement with previous reports, in this study, by 3 months after IMRT, most patients in both groups experienced progressive resolution of their physician-rated acute side effects except for xerostomia. By sparing both parotid glands, the dose to the oral mucosa was most likely lower, resulting in less grade 1 and 2 mucositis in this group [49, 50].

For this patient population differences in function scales and symptoms scores did not reach significance for either group at the 24- and 60-month timepoints after R(C)T except the symptom subscale dry mouth, where patients with unilateral gland sparing reported significantly higher symptom burden than those with bilateral gland sparing 24 months after therapy, while symptom burden did not significantly differ between groups 60 months after therapy (Table 3). This does not correspond to the physician-rated xerostomia at the 24-month timepoint, where physicians report equal symptom levels in both groups. This disparity confirms that in general, there is a low correlation between patient-reported and physician-rated xerostomia [9, 51]. Sommat et al. evaluated clinical and dosimetric predictors for physician-rated and patient-reported xerostomia in 172 patients with nasopharyngeal cancer [18]. As in the present study, xerostomia was rated based on the RTOG morbidity score and patient-rated dry mouth and sticky saliva based on the EORTC QLQ-HN35 questionnaire at the study endpoint of 24 months after completion of IMRT. The correlation between observer-rated and patient-reported outcome was weak. Although the group did not differentiate between uni- or bilateral parotid gland sparing, they could not find a dose–effect relationship between xerostomia and dose to the parotid gland. As in this study, parotid gland sparing had no effect on physician-rated xerostomia at any timepoint, while patient-reported dry mouth was worse 24 months after IMRT with unilateral parotid gland sparing.

The study did not show significant differences in QoL between the uni- and bilateral gland-sparing groups either at 24 or at 60 months after parotid-sparing IMRT, except for dry mouth. This phenomenon might be explained by Meyer et al. [52], who studied 540 HNC patients in a randomized trial also using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the EORTC-H&N35 instruments. This group concluded that baseline or early post-treatment health-related QoL is a predictor for survival in patients with LAHNC. It could be that long-term survivors, as in this population with a 60-month timepoint, are those with better health status/less treatment-related detrimental effects on QoL. It is challenging to defend this assumption because long-term data beyond 5 years on QoL in HNC patients are still scarce. There are numerous “long-term” reports presenting QoL and toxicity measuring timepoints of 1 year [53]. In 2012, Funk et al. reported long-term health-related QoL in 337 survivors of HNC [54]. Long-term was defined as a minimum of 5 years. Other QoL measurement instruments were used, but as in our study, pain and social functioning were reported to be continuously burdensome to long-term survivors 5 years and longer after completion of radiation therapy. Substantial pain was reported by 17% of patients and social disruption had the highest mean score in 80% of patients. Also, the results here confirm reports by several investigators, who concluded a lack of correlation between xerostomia or salivary gland function and overall QoL measures. A possible explanation could be that with advanced technology in HNC IMRT and increased acceptance of contouring guidelines to spare not only the parotids but also submandibular salivary glands as well as minor salivary glands (i.e., oral mucosa), sparing parotids itself has lost its impact on QoL [8, 45, 55].

The feasibility of salivary gland sparing depends on the primary site as well as on tumor and nodal classification [16]. Comparable to this study population Beetz et al. showed that with increasing nodal classification, sparing of the ipsilateral parotid gland is often not possible without compromising the initially prescribed dose [56]. This applies for primary tumors located in the oral cavity or in the oropharynx, because of the proximity to lymph node levels Ib/II [57]. From the first follow-up (3‑months after treatment) to 24-months some function scales (physical and emotional function) have changed below and some symptom scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea and financial problems) above the threshold for clinical importance (TCI) [31]. At the 24- and 60-month follow-ups, function and symptom scales do not reach clinical relevance. Giesinger et al., who first defined the threshold of clinical importance (TCI), looked at almost 500 patients, including 7.9% with HNC, throughout Europe and concluded that with the TCI the EORTC QLQ-C30 is one of the most robust measuring tools to assess functional health, symptoms, and global QoL. As in this study, similar changes in QoL over time have been reported and are in line with previous reports, suggesting that rehabilitation after multimodal treatment for LAHNC can take a year or more [7, 56, 58]. One of the more critical findings of the study is that LAHNC seems to be associated with financial issues for the majority of patients. Patients in both groups scored the symptom subscale emotional and financial problems above the TCI [31] throughout the study period. There was no difference between the groups at the follow-up timepoints. According to work by Massa et al., who reviewed and compared the financial burden in a total of more than 17,000 patients, including patients with HNC and patients with other cancers, the financial burden for HNC patients is substantial. Traditionally the majority of HNC patients have a poorer health status as well as a low socioeconomic status (SES) prior to their diagnosis, and therefore start underprivileged. Costs caused by unemployment, medical expenses/co-payments for prescriptions, and over-the-counter drugs are an additional burden to these patients [59].

In an earlier analysis of the study, the data showed that patients with low SES and LAHNC score financial problems above the TCI during the observation period of 24 month after IMRT, while in patients with high SES, the score drops below the TCI by 12 months [60]. In a recent study in a population of German cancer patients, the out-of-pocket payments in cancer patients were significant and the researchers concluded that these payments are an additional burden to cancer patients, especially in certain subgroups like low-income groups [61]. Also, according to Koch et al., the rate of employment in German long-term surviving HNC patients drops from three quarters before diagnosis to one third at an average of 66.8 months after treatment, which might also be an indicator for decreasing scores for financial function [62].

Critical comments

Some limitations of the present study should be considered. The remaining study sample size at the 60-month timepoint was relatively small, which is inherent to the nature of the disease. Nonetheless, one of the strengths of this study is the long follow-up interval of 60 months, with completed QoL questionnaires at all three timepoints. Observational studies, while less rigorously controlled than randomized trials, have the advantage of more accurately reflecting daily clinical practice. Before any treatment commenced, all patients were reviewed in a multidisciplinary tumor board. Diagnostic and therapeutic interventions were standardized and performed in a single institution.

Conclusion

This analysis has demonstrated that patients with LAHNC treated with IMRT and surviving for 5 years experience treatment-related physician-reported toxicity to a similar extent, independent of sparing of one or both parotid glands. Unilateral or bilateral parotid-sparing RT does not seem to impact the magnitude of change in of QoL; however, after 60 months, xerostomia-related issues (dry mouth and sticky saliva) persist in both groups. Most symptom scores are nearly stable between 24 and 60 months after parotid-sparing IMRT, while emotional function is decreased. The financial impact of the disease and the associated burden of medical expenses, out-of-pocket-payments, and co-payments pose an additional risk to unmet needs in this special patient population and their long-term QoL. For interpretation of the results, defined TCIs for the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 would be helpful to determine clinical relevance. The results of the study suggest that long-term survivors will most likely will benefit from early medical intervention as well as from emotional and financial support within survivorship programs.

References

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf. Accessed 5 September 2020

Jabbari S et al (2005) Matched case-control study of quality of life and xerostomia after intensity-modulated radiotherapy or standard radiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer: initial report. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 63(3):725–731

Jellema AP et al (2007) Impact of radiation-induced xerostomia on quality of life after primary radiotherapy among patients with head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 69(3):751–760

Abel E et al (2017) Impact on quality of life of IMRT versus 3‑D conformal radiation therapy in head and neck cancer patients: a case control study. Adv Radiat Oncol 2(3):346–353

Nutting CM et al (2011) Parotid-sparing intensity modulated versus conventional radiotherapy in head and neck cancer (PARSPORT): a phase 3 multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 12(2):127–136

Jensen SB et al (2019) Salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia in head and neck radiation patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2019(53):lgz016. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgz016

Tribius S et al (2015) Residual deficits in quality of life one year after intensity-modulated radiotherapy for patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer. Strahlenther Onkol 191(6):501–510

Mogadas S et al (2020) Influence of radiation dose to pharyngeal constrictor muscles on late dysphagia and quality of life in patients with locally advanced oropharyngeal carcinoma. Strahlenther Onkol 196(6):522–529

Little M et al (2012) Reducing xerostomia after chemo-IMRT for head-and-neck cancer: beyond sparing the parotid glands. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 83(3):1007–1014

Tribius S et al (2013) Xerostomia after radiotherapy. What matters—Mean total dose or dose to each parotid gland? Strahlenther Onkol 189(3):216–222

Roesink JM et al (2005) A comparison of mean parotid gland dose with measures of parotid gland function after radiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer: implications for future trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 63(4):1006–1009

Eisbruch A et al (1999) Dose, volume, and function relationships in parotid salivary glands following conformal and intensity-modulated irradiation of head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 45(3):577–587

Deasy JO et al (2010) Radiotherapy dose-volume effects on salivary gland function. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 76(3 Suppl):S58–S63

Price RE et al (1995) Effects of continuous hyperfractionated accelerated and conventionally fractionated radiotherapy on the parotid and submandibular salivary glands of rhesus monkeys. Radiother Oncol 34(1):39–46

Lombaert IM et al (2008) Rescue of salivary gland function after stem cell transplantation in irradiated glands. PLoS ONE 3(4):e2063

Hawkins PG et al (2018) Sparing all salivary glands with IMRT for head and neck cancer: longitudinal study of patient-reported xerostomia and head-and-neck quality of life. Radiother Oncol 126(1):68–74

Jellema AP et al (2007) Unilateral versus bilateral irradiation in squamous cell head and neck cancer in relation to patient-rated xerostomia and sticky saliva. Radiother Oncol 85(1):83–89

Sommat K et al (2019) Clinical and dosimetric predictors of physician and patient reported xerostomia following intensity modulated radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal cancer—A prospective cohort analysis. Radiother Oncol 138:149–157

Teng F et al (2019) Reducing xerostomia by comprehensive protection of salivary glands in intensity-modulated radiation therapy with helical tomotherapy technique for head-and-neck cancer patients: a prospective observational study. Biomed Res Int 2019:2401743

Bernier J, Vermorken JB, Koch WM (2006) Adjuvant therapy in patients with resected poor-risk head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 24(17):2629–2635

Cooper JS et al (2004) Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 350(19):1937–1944

Cooper JS et al (2012) Long-term follow-up of the RTOG 9501/intergroup phase III trial: postoperative concurrent radiation therapy and chemotherapy in high-risk squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 84(5):1198–1205

Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF (1995) Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 31(5):1341–1346

N.A. (1995) LENT SOMA scales for all anatomic sites. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 31(5):1049–1091

Rubin P et al (1995) EORTC Late Effects Working Group. Overview of late effects normal tissues (LENT) scoring system. Radiother Oncol 35(1):9–10

Rubin P et al (1995) RTOG Late Effects Working Group. Overview. Late Effects of Normal Tissues (LENT) scoring system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 31(5):1041–1042

Aaronson NK et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85(5):365–376

Bjordal K et al (1994) Development of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) questionnaire module to be used in quality of life assessments in head and neck cancer patients. EORTC Quality of Life Study Group. Acta Oncol 33(8):879–885

Fayers PM, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, EORTC Quality of Life Study Group, - (2001) The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual, 3rd edn. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Brussels

King MT (1996) The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res 5(6):555–567

Giesinger JM et al (2020) Thresholds for clinical importance were defined for the European organisation for research and treatment of cancer computer adaptive testing core-an adaptive measure of core quality of life domains in oncology clinical practice and research. J Clin Epidemiol 117:117–125

Arraras JI et al (2002) The EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) quality of life questionnaire: validation study for Spain with head and neck cancer patients. Psychooncology 11(3):249–256

Singer S et al (2013) Performance of the EORTC questionnaire for the assessment of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients EORTC QLQ-H&N35: a methodological review. Qual Life Res 22(8):1927–1941

Singer S et al (2009) Validation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-H&N35 in patients with laryngeal cancer after surgery. Head Neck 31(1):64–76

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Academic Press, New York

Osoba D et al (1998) Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 16(1):139–144

King AJ et al (2015) Prostate cancer and supportive care: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis of men’s experiences and unmet needs. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 24(5):618–634

Paterson C et al (2017) Unmet supportive care needs of men with locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer on hormonal treatment: a mixed methods study. Cancer Nurs 40(6):497–507

Moore HCF (2020) Breast cancer survivorship. Semin Oncol 47(4):222–228

Koh J et al (2019) Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma survivorship care. Aust J Gen Pract 48(12):846–848

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.3322/caac.21492. Accessed 31 August 2020

Bjordal K, Mastekaasa A, Kaasa S (1995) Self-reported satisfaction with life and physical health in long-term cancer survivors and a matched control group. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 31B(5):340–345

Pow EH et al (2006) Xerostomia and quality of life after intensity-modulated radiotherapy vs. conventional radiotherapy for early-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma: initial report on a randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 66(4):981–991

Vergeer MR et al (2009) Intensity-modulated radiotherapy reduces radiation-induced morbidity and improves health-related quality of life: results of a nonrandomized prospective study using a standardized follow-up program. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 74(1):1–8

Ringash J et al (2005) Postradiotherapy quality of life for head-and-neck cancer patients is independent of xerostomia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 61(5):1403–1407

Hunter KU et al (2013) Toxicities affecting quality of life after chemo-IMRT of oropharyngeal cancer: prospective study of patient-reported, observer-rated, and objective outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 85(4):935–940

Richards TM et al (2017) The effect of parotid gland-sparing intensity-modulated radiotherapy on salivary composition, flow rate and xerostomia measures. Oral Dis 23(7):990–1000

Elting LS et al (2008) Patient-reported measurements of oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy: demonstration of increased frequency, severity, resistance to palliation, and impact on quality of life. Cancer 113(10):2704–2713

Tribius S et al (2012) Global quality of life during the acute toxicity phase of multimodality treatment for patients with head and neck cancer: can we identify patients most at risk of profound quality of life decline? Oral Oncol 48(9):898–904

Jellema AP et al (2005) Does radiation dose to the salivary glands and oral cavity predict patient-rated xerostomia and sticky saliva in head and neck cancer patients treated with curative radiotherapy? Radiother Oncol 77(2):164–171

Meirovitz A et al (2006) Grading xerostomia by physicians or by patients after intensity-modulated radiotherapy of head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 66(2):445–453

Meyer F et al (2012) Predictors of severe acute and late toxicities in patients with localized head-and-neck cancer treated with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 82(4):1454–1462

El-Deiry MW et al (2009) Influences and predictors of long-term quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 135(4):380–384

Funk GF, Karnell LH, Christensen AJ (2012) Long-term health-related quality of life in survivors of head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 138(2):123–133

Scrimger R et al (2007) Correlation between saliva production and quality of life measurements in head and neck cancer patients treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol 30(3):271–277

Beetz I et al (2014) The QUANTEC criteria for parotid gland dose and their efficacy to prevent moderate to severe patient-rated xerostomia. Acta Oncol 53(5):597–604

Robbins KT (1992) Head and neck oncology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 106(1):7–8

Veldeman L et al (2008) Evidence behind use of intensity-modulated radiotherapy: a systematic review of comparative clinical studies. Lancet Oncol 9(4):367–375

Massa ST et al (2019) Comparison of the financial burden of survivors of head and neck cancer with other cancer survivors. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 145(3):239–249

Tribius S et al (2018) Socioeconomic status and quality of life in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer. Strahlenther Onkol 194(8):737–749

Buettner M et al (2019) Out-of-pocket-payments and the financial burden of 502 cancer patients of working age in Germany: results from a longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer 27(6):2221–2228

Koch R et al (2015) Employment pathways and work-related issues in head and neck cancer survivors. Head Neck 37(4):585–593

Giesinger JM, Loth FLC, Aaronson NK et al (2020) Thresholds for clinical importance were defined for the European organisation for research and treatment of cancer computer adaptive testing core-an adaptive measure of core quality of life domains in oncology clinical practice and research. J Clin Epidemiol 117:117–125

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

S. Tribius, S. Haladyn, H. Hanken, C.-J. Busch, A. Krüll, C. Petersen, and C. Bergelt declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants or on human tissue were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1975 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Supplementary Information

66_2020_1737_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplemental data, Panel 1: Quality of life at 3, 24, and 60 months after parotid-sparing IMRT (EORTC QLQ-C30) including the threshold for clinical importance (TCI) as proposed by Giesinger et al. [31]

66_2020_1737_MOESM3_ESM.docx

Supplemental data Table 1: Analyses of responders (n = 59 patients 24 and 60 months after R(C)T vs. non-responders [dropout] n = 79 patients at 24 months after radiation)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tribius, S., Haladyn, S., Hanken, H. et al. Parotid sparing and quality of life in long-term survivors of locally advanced head and neck cancer after intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Strahlenther Onkol 197, 219–230 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-020-01737-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-020-01737-2