Abstract

Adolescence and young adulthood are periods of increased autonomy. Higher levels of autonomy could increase the opportunities for risky behavior such as delinquency. During these periods of transition, the role of parental control becomes less clear. Previous studies have demonstrated the association between parental control and adolescent delinquency, but few have extended examination of such association into young adulthood. The purpose of the study is to examine the association between parental control and delinquency and parental control in adolescence and young adult criminal behavior. We propose that, even though adolescents seek autonomy during this stage, lack of parental control is positively associated with delinquency and has continued influence in young adulthood. Using a national longitudinal dataset, we analyzed the relationship between parental control and delinquency. Findings from regression analyses indicated that lack of parental control had a positive association with delinquency both concurrently and longitudinally into young adulthood. When analyzing delinquency in young adulthood, females reported a lower level of delinquency and younger age was associated with more delinquent behavior. Unexpectedly, parents’ college education was positively associated with delinquency in young adulthood. The findings suggest that parental control is still influential through the period of adolescence and early parental control is still influential in young adulthood. Ways to practice parental control and implications of results are further discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

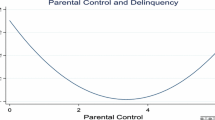

Adolescence is a time of transition for both adolescents and their parents. It has been called a period of storm and stress (Hall 1904) due to adolescents’ increasing needs for autonomy. On one hand, adolescents should be given the room by parents to explore, develop, and grow (Erikson 1968; Steinberg and Silk 2002). On the other hand, adolescents are still not fully mature, therefore parents are still very important in providing guidance and monitoring (Steinberg and Silk 2002). Because of the need for parents to renegotiate their parenting roles and modify their parenting behaviors (e.g., granting more autonomy) to accommodate adolescents’ development during this unique period (Baumrind 1967; Steinberg and Silk 2002), the role of parental control becomes less clear. Some researchers suggest that too much parental control could prevent adolescents from exploring themselves and establishing autonomy (Nye 1958), whereas others believe that parental control is crucial for adolescents (Smetana et al. 2005), especially regarding adolescents’ delinquent behavior. However, the role of early parental control in criminal behavior of young adults is less clear.

Aspects of Baumrind’s (1965) parenting typology are used to understand the relationship between parental control and delinquency in adolescence and young adulthood. Baumrind categorized parenting behaviors on levels of demandingness and responsiveness when studying children (Baumrind 1965). Parenting behaviors that were high in demandingness and high in responsiveness resulted in better outcomes for children. Within this study we focused on the aspect of parental demandingness, which has also been labeled parental control by other scholars (Maccoby and Martin 1983). Therefore parents with high parental control should have children with better outcomes.

Similar to small children, Baumrind (2005) suggested that adolescents should show better outcomes with parents who are high in demandingness and responsiveness. However, due to the unique stage of adolescence, the role of parental control needs to be further explored. Adolescence is a stage of autonomy seeking and independence, therefore parental control could be seen as a force preventing such exploration and development (Nye 1958).

Delinquency and Young Adult Criminal Behavior

Between 2007 and 2008, juvenile arrest decreased three percent (Puzzanchera 2008). Despite this decrease, approximately 2.11 million arrests were made of youth under the age of 18 in 2008 (Puzzanchera). Literature has found that antisocial behavior such as delinquency peaks in adolescence, beginning in early adolescence and decreasing around late adolescence (Moffitt 1993). However, recent studies have found that delinquent behavior may continue in late adolescence and even into young adulthood (Piquero et al. 2001). The majority of adolescents that engage in delinquent acts do not become career criminals (Mulvey 2011). In fact, multiple trajectories of delinquency have been found from the Pittsburg Youth Study, which consisted of following males from approximately age 6–20 for 14 years (Hoeve et al. 2008). After following male youth over the period of 14 years, Hoeve et al. (2008) found that approximately 60 % of them committed no delinquent acts or non -serious delinquent acts over time. However, almost a quarter of the sample continued to commit serious delinquent acts over those 14 years. In the Pathways to Desistance study, Mulvey (2011) found a higher percentage of adolescents that continued criminal activity into young adulthood. This study followed 1,354 serious juvenile offenders ages 14–18 over seven years and found that approximately half of those considered serious offenders continued committing crimes into adulthood.

In support of previous finding Piquero et al. (2001) followed the arrest record of male criminal offenders between the ages of 16 and 22 for 7 years. The results suggest that overall criminal behavior peaked during late adolescence and early twenties and decreased afterwards. The previous studies suggest that delinquent behavior is a concern for adolescents and criminal behavior continues to be a concern as they transition into adulthood.

Previous literature has found gender differences in delinquent behavior. Male adolescents are more likely than female adolescents to be involved in delinquent behavior (Moffitt and Caspi 2001; Moore and Hagedorn 2001). Even in extreme antisocial behavior such as gang involvement, female adolescents were less likely to commit serious, violent acts than males (Moore and Hagedorn 2001). Even though male adolescents historically report more delinquent acts than females, the rates of female delinquency have increased, specifically for simple assault (12 %), larceny-theft (4 %) and DUI (7 %; Puzzanchera 2008). This trend in gender differences continues when examining trajectories of delinquent behavior. Moffitt and Caspi (2001) found a lower male to female ratio (1.5:1) of adolescent limited antisocial behavior than those on life-course persistent path (10:1). This suggests that more males continue with antisocial behavior over their lifetime than females. Also, it was found that the difference in lifetime antisocial behavior between males and female is associated with differences in parenting practices.

Parental Control and Adolescent Delinquency

As children become adolescents, they want to make more decisions about their friends, clothes, and what to watch on television (Steinberg and Silk 2002). Adolescents want more decision making power and want to act on their decisions. Such behavioral autonomy is needed to help adolescents through the process of identity formation to transition into adulthood. Demands for behavioral autonomy can test the limits of parental control. On one hand, increases in parental control during this time period may result in a power struggle and conflict between parents and adolescents (Steinberg & Silk). On the other hand, however, adolescents are still quite immature and are prone to risky behavior. When adolescents lack parental control and are left with large amount of unsupervised time, they are more likely to engage in risky behavior (Barnes et al. 2006; Borawksi et al. 2003). In fact, adolescents at this stage are particularly vulnerable to the consequences of delinquent behavior, such as drug use (McCord 1990; Steinberg and Silk 2002), possibly due to lower decision making ability, especially for those involved in the criminal justice system (Mulvey et al. 2010). This suggests that parental control is still critical for adolescents. Therefore, despite the need and want for autonomy, parental control is very much needed and important for adolescent development, especially regarding delinquent behavior (Steinberg 1990).

Several studies have demonstrated the association between parental control and adolescent delinquency. For example, Hoeve et al. (2009) conducted a meta-analysis of parenting behavior and delinquency of children and adolescents, and found that there was a large negative correlation between parental control and delinquency with an effect size of -.19. Borawksi et al. (2003) found in a sample of adolescents with an average age of 16 that higher levels of negotiated unsupervised time correlated with more sexual activity and drug and alcohol use. Other studies found that lack of parental control was associated with higher levels of delinquent behavior in adolescent girls with an average age of 15 (Haynie 2003), 10th grade male adolescents (Chen 2010), and rural adolescents (Cottrell et al. 2003). Supporting these results, Sameoff et al. (2004) found that after controlling for other contextual variables (e.g. neighborhood, race, gender, peers, etc.), consistent parental control predicted externalizing behaviors of seventh graders in Maryland.

Early Parental Control and Young Adult Criminal Behavior

Previous studies have demonstrated the association between parental control and adolescent delinquency. In this study, we intend to add the to the literature concerning the relationship between parental control in adolescence and young adult criminal behavior. Using data from the Unraveling Juvenile Delinquency study, Sampson and Laub (1993)did not find a significant relationship between parental supervision in childhood and juvenile delinquency or adult criminal behavior. In a 30 year follow up of children seen at a psychiatric facility, Robbins (1966) found that parents that were too lenient had a higher percentage of adult children diagnosed with a “sociopathic personality”. While “sociopathic personality” is not delinquent behavior, the study supports the long-term effects of parental control. However, when studying the association between parenting styles and adult criminal behavior, early indulgent parenting positively related to adult criminal behavior (Schroeder et al. 2010).

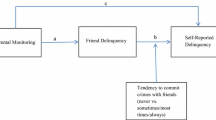

Several mechanisms could explain the effects of early parental control on young adults. First, even though young adults are likely no longer living with their parents and under their parents’ immediate control, previous messages of parental control could be internalized and still exert effects on young adults and prevent criminal behavior. Second, because behavioral continuity is well documented (Elder 1985), lack of parental control could lead to adolescent delinquency, which in turn leads to such behavior continuing into young adulthood. Third, in addition to behavioral continuity, adolescent delinquency could lead to a series of negative life events (e.g., less stable lives, Mulvey 2011), which could result in externalizing problems in young adulthood. Therefore, parental control in adolescence could be negatively associated with criminal behavior in young adulthood. Few studies have examined this association using a national representative sample.

Previous findings suggest that adequate parental control was negatively associated with adolescent delinquency. However, these studies also have several limitations. First, several studies used small and non-representative samples. For example, findings from Hoeve et al. (2008) were based on a sample of youth in one city. Also, Bean, Barber, and Crane (2006) used a sample of African American youth in Tennessee to show that parental behavioral control was negatively related to delinquency.

Second, few studies have examined the effect of parental control on delinquency during adolescence over time. Many studies used correlational data from one time point (Bean et al. 2006; Seydlitz 1991). When multiple data points were used, the sample was not nationally representative (Hoeve et al. 2008; Smetana et al. 2005; Sampson and Laub 1993). In summary, most studies are cross-sectional and continued longitudinal studies extending the association between parental control and adolescent delinquency into later life stages are needed to replicate finding from previous studies and to study not only the immediate effect of parental control on adolescent delinquency, but also the long-term effects parental control during adolescence.

In this study, we used a large, nationally representative, and longitudinal sample of adolescents and their parents to examine the association between parental control and delinquency in adolescence and parental control in adolescence and young adult criminal behavior. Based on Baumrind’s theory, we hypothesized that there is a positive association between low parental control and adolescent delinquency. Because behaviors tend to show continuity over time (Elder 1985) and parental influence goes beyond childhood and adolescence (Nelson et al. 2011), we also propose that low parental control during adolescence will be positively associated with criminal behavior in young adulthood. To further improve upon earlier studies, this study will also control for individual and demographic factors because previous studies have indicated an association between adolescent delinquency and these variables, including adolescent gender (Griffin et al. 2000; Mack and Leiber 2005; Seydlitz 1991); race and ethnicity (Blum et al. 2000); parental education (Cui et al. 2007); and family structure (Blum et al. 2000; Demuth and Brown 2004; Griffin et al. 2000; Kowaleski-Jones and Duniforn 2006). Controlling for these variables will ensure that the association between parental control and adolescent delinquency is not a mere artifact.

Method

Sample and Procedures

In this study, we used data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). Add Health data came from a sample of adolescents from 132 U.S. schools, in grades 7–12 during the 1994–1995 school year. A multistage, stratified, cluster sampling design was used in the Add Health study. Information about sample and procedures can be obtained from Harris et al. (2008) and at the website: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

In 1995, data for Wave 1 were collected through in-home interviews to students in grades 7–12 (N = 20,745) when participants were 12–21 years old. Information was collected about social and demographic characteristics of respondents, household structure, family composition and dynamics, delinquent behaviors, sexual partnerships, and formation of romantic partnerships. Data were then collected a year later for Wave II from the same participants except from those who graduated from high school (N = 14,738). Wave III data were collected in 2001 (N = 15,197) when participants were 18–27 years old. The current study used data from Wave I and Wave III. Of the original 20,745 participants in Wave I, 18,924 had valid sampling weights. And of the 18,924 adolescents, 17,636 had complete data on variables of interested. Of the 15,197 participants in Wave III, 14,322 had valid (longitudinal) sampling weights, and 13,358 had complete data. As a result, our analyses were based on N = 17,636 for Wave I and N = 13,358 from Wave I to Wave III. Attrition analyses suggested that male adolescents, African Americans, and those in lower grade levels in Wave I were more likely to have dropped out from the survey.

Adolescent Delinquency (Wave I) and Young Adult Criminal Behavior (Wave III)

For this study we used delinquency measured at Wave I for adolescents and criminal behavior at Wave III for young adults. To keep it consistent, only the same items across Wave I and Wave III were used. At both waves, delinquency/criminal behavior was measured using seven items asking: During the past 12 months, how often did you: deliberately damage property, steal something worth more than $50, go into a house or building to steal something, use or threaten to use a weapon to get something from someone, sell marijuana or other drugs, steal something worth less than $50, and take part in a fight where a group of your friends was against another group. The items ranged from 0 = never to 3 = 5 or more times. The seven items were summed for each wave. The alphas were .74 for Wave I and .65 for Wave III. A higher score reflected a higher level of delinquent behavior.

Lack of Parental Control (Wave I)

Lack of parental control was measured using six items, asking the adolescents whether their parents let them make their own decisions about: the time you must be home on weekend nights, the people you hang around with, what you wear, how much television you watch, which television programs you watch, and what time you go to bed on week nights. The items were coded as 0 = no and 1 = yes. The six items were then summed together. A higher score reflected a lower level of parental control (i.e., lack of parental control). The alpha was .60. These items have been used to measure parental control in previous studies (Morgo-Wilson 2007).

Control Variables (Wave 1)

Other demographic variables were added to the analysis as control variables. All control variables used were measured at Wave I. Age was measures in years. Gender was coded as 0 = male and 1 = female. Race and ethnicity was measure through five dummy variables White (reference group), African American, Asian, Hispanic and Other. Also, family structure consisted of five dummy variables, two-biological parent families (reference group), stepfamilies, single-mother families, single-father families, and other families (Cavanagh et al. 2008). Adolescent’s report of parent’s education was also used. Reponses included 1 = eighth grade or less to 9 = professional training beyond a four-year college or university, no schooling was coded as 0. Then four dummy variables were created, college education or more, some college education, high school graduation (reference group), or less than a high school education, for the parent with the highest education when education of both parents were reported.

Results

When analyzing the data, we adjusted the stratified and clustered data design following patterns of previous Add Health researchers (Chantala and Tabor 1999). The data was adjusted using Stata’s “svy” estimation. Using svy estimation method in the statistical analysis allowed us to take into account oversampling of certain individuals at first data collection in Wave I. Separate weighted variables were used depending on which waves were used. Stata’s “svy” was also used to correct standard errors for data clustering (e.g. participants nested in schools) in Wave I (Chantala 2006).

Demographic Information

Descriptive statistics can be found in Table 1. Adolescents in Wave I ranged in ages from 12 to 21, with a mean age of 15.90. Approximately half of the adolescents in the sample were male. Regarding race and ethnicity, 68.58 % identified as White, 11.44 % as Hispanic, 15.34 % as African American, 3.40 % as Asian, and 1.24 % as other. Among the families, 57.95 % came from a two biological parent home, 16.56 % were from stepfamilies, 19.47 % were from single mother families, 2.95 % were from single father families, and 3.07 % were from other types of families. About a third of adolescents reported that their parents had a high school diploma and another third reported that their parents had a college degree.

Regarding the variables of interests, the mean for lack of parental monitoring was 4.33, with a standard deviation of 1.40 and a range from 0 to 6. The mean value for adolescent delinquency at Wave I was 1.13. The majority of the adolescents reported a low level of delinquency, though a few reported very high level of delinquent involvement. Nevertheless, the standard deviation (2.18) indicated a significant degree of variation among individuals. The mean for delinquency in young adulthood in Wave III was .61, indicating an overall decline in delinquency from Wave I to Wave III. With these preliminary analyses, we now turn to the hypotheses testing.

Hypothesis Testing

First, we regressed lack of parental control on adolescent delinquency concurrently at Wave I. Adolescent gender, age, and other demographic variables were also included. As shown in Table 2, lack of parental control was significantly associated with adolescent delinquency at Wave I (b = .077, p < .01). Such effect was significant even after controlling for other demographic variables. Regarding the control variables, female adolescents reported significantly lower level of delinquency (b = −.114, p < .01). Compared with White adolescents, Hispanic adolescents reported significantly higher level of delinquency. Finally, compared with adolescents from two-biological parent families, adolescents from stepfamilies, single-mother families, single-father family, and other families were all significantly more likely to engage in delinquent behavior.

Second, we regressed lack of parental control at Wave I on criminal behavior in young adulthood at Wave III. As shown in Table 3, lack of parental control was still significantly associated with criminal behavior in young adulthood at Wave III (b = .041, p < .01). Such effect was significant after controlling for earlier adolescent delinquency (at Wave I) and other demographics. As expected, earlier adolescent delinquency significantly predicted criminal behavior in young adulthood (b = .144, p < .01). Regarding control variables, females reported a lower level of criminal behavior and younger age was associated with more criminal behavior. Unexpectedly, parents’ college education was positively associated with criminal behavior in young adulthood.

Discussion

We hypothesized that there would be a positive association between low parental control and delinquent behavior both concurrently in adolescence and longitudinally into young adulthood. Using data from Add Health, results from regression analyses supported our hypotheses. We found that lack of parental control was associated with higher level of delinquency in adolescence. The same low parental control in adolescence was also associated with criminal behavior in young adulthood. Such findings were consistent with Baumrind’s parenting theory and previous studies, but extended previous studies in several ways.

Results from this study support previous and current literature regarding parental control and delinquency. Previously, it was pointed out that children and adolescents with low parental behavioral control had higher delinquent behaviors (Baumrind 2005). Previous literature showed that parental behavioral control is essential in predicting positive outcome for young children and adolescents. Findings from our study also point out that early parental control is still essential in predicting criminal behavior of young adults as well as delinquency of adolescents.

Adolescence can be a confusing time for parents and adolescents. Previous research shows that adolescents should have certain autonomy to grow and develop a sense of self (Steinberg and Silk 2002). Yet, too much autonomy can result in negative outcomes such as delinquency (Chen 2010). As our results show, the level of parental control is an important factor in adolescent’s delinquent behavior. Steinberg and Silk (2002) suggested that adolescents should have a say in what they are doing, yet parents should have the final decision for healthy adolescent development. Parents should continue to control what adolescents watch on television, who they associate with, and how much unsupervised time they are allowed out of the house, to decrease the chances of their child being involved in delinquent behavior. This implies that parents still need to have more control over adolescent’s behavior and decision-making through this transition, to alleviate risky behavior such as delinquency.

It is not surprising that few studies were found concerning parental control and young adulthood. As previously mentioned, young adulthood is an ambiguous developmental period. Those in this stage have the autonomy similar to adults, but not the responsibility (Arnett 2000). Those in this stage may be more likely to be involved in criminal activities, due to cumulative lower parental control and the lack of adult responsibilities for this developmental period (Arnett). Previous literature has found that delinquent behavior of offenders seemed to peak during late adolescence and young adulthood (Piquero et al. 2001). It has also been found that other life events such as marriage and employment decrease the chances of future criminal behavior of late adolescents and those in the stage of young adulthood (Piquero et al.). Our research suggests that early parental control is another factor associated with criminal behavior of those in young adulthood. Parental control in adolescence is also important because parental control exerted in young adulthood may not be well received by those in the stage of life, and when parents displayed high control and low warmth more issues with various internalizing and externalizing behaviors were found (Nelson et al. 2011). Therefore, as our results suggest, the lasting effects of parental control during adolescence are crucial to decreasing criminal behavior of young adults.

Besides theoretical contributions, there are methodological strengths of the current study. First, this study was longitudinal and prospective, following participants’ delinquency and criminal behavior from adolescence to young adulthood. Few studies were found that analyzed the effect of parental control on delinquency during adolescence longitudinally (Hoeve et al. 2008; Smetana et al. 2005; Sampson and Laub 1993). When longitudinal data was used, it was usually from non-representative samples. Therefore, the second strength of this study is the analysis of a representative and large sample. Third, this study controlled for earlier level of delinquency when predicting criminal behavior in young adulthood. The significant association between early parental control and criminal behavior in young adulthood suggested the effect of parental control beyond the continuity of delinquent behavior from adolescence to young adulthood. Finally, this study also controlled for other demographic variables when analyzing the relationship between parental control and delinquency. The inclusion of these control variables increased our confidence that the association found between parental control and delinquency was not spurious.

There are some limitations to the current study. The use of adolescents’ report of parental control may inflate the association between delinquency and parental control. Also, parental control was not examined at later waves due to the constraints of the data. Even though we used longitudinal data, the analysis is correlational by nature, therefore casual conclusions cannot be made. Future studies should research the change in parental control, observing if the trajectory parallels that of delinquent and criminal behavior. Also, caution should be used to interpret the findings given that participants who dropped out of the survey were excluded from the current study. However, the longitudinal weight was used to minimize attrition biases, which increased our confidence of the generalizability of the findings. Finally, the outcome delinquency was quite skewed. But previous studies have shown that the regression analyses were quite robust to non-normality, especially with such a big sample.

Despite the limitations, this study adds to the literature concerning the importance of parental control to adolescent delinquent behavior and criminal behavior of young adults by replicating previous findings using a large and nationally representative sample. Results from this study can be used to inform parenting programs and clinical practice. Adolescence and young adulthood are not only ambiguous periods for the adolescents, but for parents as well. Parents may need guidance to navigate this unknown territory. Future studies should explore the association between early parental control and other life events with delinquent behavior of adolescents and in their transition to adulthood. This study, along with future studies concerning this topic can inform parenting programs that focus on adolescence and the transition to adulthood.

References

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from late teens through twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

Barnes, G. M., Hoffman, J. H., Welte, J. W., Farrell, M. P., & Dintcheff, B. A. (2006). Effects of parental monitoring and peer deviance on substance use and delinquency. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 1084–1104.

Baumrind, D. (1965). Parental control and parental love. Children, 12, 230–234.

Baumrind, D. (1967). Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 75, 43–88.

Baumrind, D. (2005). Patterns of parental authority and adolescent autonomy. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 108, 61–69.

Bean, R. A., Barber, B. K., & Crane, D. R. (2006). Parental support, behavioral control, and psychological control among African American youth: The relationships to academic grades, delinquency, and depression. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 1335–1355.

Blum, R. W., Beuhring, T., Shew, M. L., Bearinger, L. H., Sieving, R. E., & Resnick, M. D. (2000). The effects of race/ethnicity, income, and family structure on adolescent risk behavior. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 1879–1884.

Borawksi, E. A., Ievers-Landis, C. E., Lovegreen, L. D., & Trapl, E. S. (2003). Parental monitoring negotiated unsupervised time and parental trust: The role of perceived parenting practices in adolescent health risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33, 60–70.

Cavanagh, S. E., Crissey, S. R., & Raley, R. K. (2008). Family structure history and adolescent romance. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 698–714.

Chantala, K. (2006). Guidelines for analyzing Add Health data. Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Chantala, K., & Tabor, J. (1999). Strategies to perform a design-based analysis using the Add Health data. Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Chen, X. (2010). Desire for autonomy and adolescent delinquency: a latent growth curve analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37, 989–1004.

Cottrell, L., Li, X., Harris, C., D’Alessandri, D., Atkins, M., Richardson, B., et al. (2003). Parent and adolescent perceptions of parenting monitoring and adolescent risk involvement. Parenting Science and Practice, 3, 179–195.

Cui, M., Donnellan, M. R., & Conger, R. D. (2007). Reciprocal influences between parents’ marital problems and adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1544–1552.

Demuth, S., & Brown, S. L. (2004). Family structure, family processes, and adolescent delinquency: The significance of parental absence versus parental gender. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 41, 58–81.

Elder, G. H. (1985). Life course dynamics: Trajectories and transitions, 1968–1980. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. NY: Norton & Company.

Griffin, K. W., Botvin, G. J., Schier, L. M., Diaz, T., & Miller, N. L. (2000). Parenting practices as predictors of substance use, delinquency, and aggression among urban minority youth: Moderating effects of family structure and gender. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 14, 174–184.

Hall, G. S. (1904). Adolescence: Its psychology and its relation to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education (Vols. I & II). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Harris, K. M., Halpern, C. T., Entzel, P., Tabor, J., Bearman, P. S., & Udry, J. R. (2008). The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research design [www document]. URL: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

Haynie, D. L. (2003). Contexts of risk? Explaining the link between girls’ pubertal development and their delinquency involvement. Social Forces, 82, 355–397.

Hoeve, M., Blokland, A., Semon Dubas, J., Loeber, R., Gerris, J. R. M., & van der Laan, P. H. (2008). Trajectories of delinquency and parenting styles. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 223–235.

Hoeve, M., Semon Dubas, J., Eichelsheim, V. I., van der Laan, P. H., Smeenk, W., & Gerris, J. R. M. (2009). The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 749–775.

Kowaleski-Jones, L., & Duniforn, R. (2006). Family structure and community context: Evaluating influences on adolescent outcomes. Youth & Society, 38, 110–130.

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In P. Mussen (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology Vol.4. New York: Wiley.

Mack, K. Y., & Leiber, M. J. (2005). Race, gender, single-mother households, and delinquency. Youth & Society, 37, 115–144.

McCord, J. (1990). Problem behaviors. In S. S. Feldman & G. R. Elliot (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 414–430). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-Limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 4, 674–701.

Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2001). Childhood predictors differentiate life-course persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways among males and females. Development and Psychopathology, 13, 355–375.

Moore, J. & Hagedorn, J., Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. (2001). Female gangs: A focus on research (NCJ Publication No. 188159). Retrieved from http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/188159.pdf.

Morgo-Wilson, C. (2007). The influence of parental warmth and control on Latino adolescent alcohol use. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 30, 89–105.

Mulvey, E. (2011). Highlights from pathways to desistance: A longitudinal study of serious adolescent offenders. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention NCJ 230971.

Mulvey, E.P, Schubert, C.A. Chassin, L. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2010). Substance abuse and delinquent behavior among serious adolescent offenders. (NCJ Publication No. 232790). Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/232790.pdf.

Nelson, L. J., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Christensen, K. J., Evans, C. A., & Carroll, J. S. (2011). Parenting in young adulthood: An examination of parenting clusters and correlates. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 730–743.

Nye, I. F. (1958). Family relationships and delinquent behavior. Westport, CT: Greenwod Press.

Piquero, A.R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P., & Haapanen, R. (2001). Crime in emerging adulthood: Continuity and change in criminal offending (NCJ Publication 186735). Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/186735.pdf.

Puzzanchera, C., Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. (2008). Juvenile arrest 2008 (NCJ Publication No. 228479). Retrieved from http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/228479.pdf.

Robbins, L. N. (1966). Deviant children grown up: A sociological and psychiatric study of sociopathic personality. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Company.

Sameoff, A. J., Peck, S. C., & Eccles, J. S. (2004). Changing ecological determinants of conduct problems from early adolescence to early adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 873–896.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points through life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Schroeder, R. D., Bulanda, R. E., Giordana, P. C., & Cernkovich, S. A. (2010). Parenting and adult criminality: An examination of direct and indirect effects by race. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25, 64–98.

Seydlitz, R. (1991). The effects of age and gender on parental control and delinquency. Youth & Society, 23, 175–201.

Smetana, J., Crean, H. F., & Campione-Barr, N. (2005). Adolescents’ and parents’ changing conceptions of parental authority. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 108, 31–46.

Steinberg, L. (1990). Autonomy, conflict, and harmony in the family relationship. In S. S. Feldman & G. R. Elliot (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 255–276). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Steinberg, L., & Silk, J. S. (2002). Parenting adolescents. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting children and parenting (Vol. 1, pp. 103–133). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Acknowledgments

This study uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter, S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by a grant P01-HD31921 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgement is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harris-McKoy, D., Cui, M. Parental Control, Adolescent Delinquency, and Young Adult Criminal Behavior. J Child Fam Stud 22, 836–843 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9641-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9641-x