Abstract

Parental monitoring impacts adolescent delinquency both directly by limiting unsupervised activities and indirectly by limiting access to delinquent peers. Deviant peers may influence adolescent delinquency through a number of mechanisms, and there is a lack of clarity within the literature on distinctions between co-offending and deviant peer norms as influential mechanisms. Less is known about the impact of co-offending on the mediated relationship among parental monitoring, peer delinquency, and adolescent delinquency. The current study examined the relationship between parental monitoring, deviant peer behaviors, co-offending, and self-reported delinquency among 186 court-involved youth (12–18 years old) in a small city in the Midwest. The effects of parental monitoring on delinquency were partially mediated by delinquent peer affiliation. A moderated mediation model found that co-offending moderated the association between delinquent peer affiliation and delinquency, such that the relationship between peer delinquency and self-reported delinquency is stronger for those who co-offend.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is well documented that parenting practices and deviant peer influence both contribute to adolescent delinquent behaviors. In addition to the literature demonstrating independent effects of parenting and peer influence on delinquency (Kerr and Stattin 2000; Warr 2005), substantial work by Patterson and colleagues demonstrates that deviant peer affiliation mediates the effects of parenting, in particular parental monitoring, on youth’s engagement in delinquent acts (Ary et al. 1999; Patterson et al. 1989, 1992; Patterson and Dishion 1985; Patterson and Yoerger 1997). In this model, while peers remain the more proximal predictor of delinquency, parents exert an influence on delinquency by shaping the availability and nature of interactions with deviant peers. The link between deviant peer affiliation and delinquency has often been explained by adolescents’ well-documented tendency to engage in delinquent behavior in groups (Carrington 2009; Reiss 1986; Zimring and Laqueur 2014). However, while many adolescents co-offend, some adolescents offend alone, and not all juvenile offenses are committed in groups (Goldweber et al. 2011; McGloin and Stickle 2011).

Many studies over the last 20 years have demonstrated that parents who lack knowledge of their children’s whereabouts, activities, and acquaintances, have children who are more likely to engage in delinquent behaviors (Crouter and Head 2002; Dishion and McMahon 1998; Laird et al. 2003; Véronneau and Dishion 2010). Different dimensions of the parent–child relationship have been implicated in the risk for delinquency; low levels of child disclosure (i.e., a child sharing accurate information with his/her parents), parental solicitation (i.e., a parent asking his or her child(ren) who his or her friends are and what they do with friends), and parental control (i.e., actively setting limits and rules for a child) are all associated with increased delinquency (Keijsers et al. 2009; Kerr and Stattin 2000; Kerr et al. 2010; Lahey et al. 2008; Stattin and Kerr 2000). The development model of delinquency advanced by Patterson and colleagues (Dishion et al. 1991; Patterson et al. 1989, 1992; Patterson and Dishion 1985; Patterson and Yoerger 1997) suggests that parental monitoring can directly influence delinquency by limiting an adolescent’s opportunities to engage in unsupervised activities, and indirectly influence delinquency by limiting a youth’s affiliation with deviant peers. Based on Patterson’s model, parents’ failure to monitor their child effectively provides opportunity for the child to engage in delinquent acts and to seek out deviant peers. When parents gain knowledge of and limit their child’s activities, they are often specifically interested in decreasing their child’s interactions with deviant friends, albeit with varying levels of success (Keijsers et al. 2011; Mounts 2008). A number of researchers have confirmed Patterson’s model of delinquency development with parental monitoring influencing delinquency or similar problem behaviors both directly, as well as indirectly through affiliation with deviant peers (Ary et al. 1999; Bowman et al. 2007; Henry et al. 2001; Simons et al. 1994a, b). However, there is a lack of research examining Patterson’s model using an adjudicated, high-risk sample of adolescent offenders.

To understand the interplay of parents and peers in development of delinquency, it is important to closely examine the mechanisms of peer influence. While it is clear that adolescent delinquency is closely linked to affiliation with delinquent peers, the specific processes accounting for this association are subject to debate. Selection effects may be partly responsible, as over time adolescents who engage in delinquent behaviors consistently choose to affiliate with peers with similar levels of delinquent behaviors (Bauman and Ennett 1996; Tilton-Weaver et al. 2013; Weerman 2004). At the same time, however, substantial longitudinal evidence demonstrates that peers do exert influence on an adolescent’s behaviors over time, with adolescents increasing their engagement in delinquent behaviors to match their peers (Elliott and Menard 1996; Patterson et al. 2000). One way delinquent peers exert influence is by presenting antisocial behaviors as the norm. Exposure to antisocial group norms alters an adolescent’s attitudes towards antisocial behavior, which in turn can change the adolescent’s own behavior (Akers 1998; Sutherland 1947). At the same time, deviant peers directly reinforce adherence to antisocial group norms by both talking about antisocial behavior in positive terms and verbally approving of each other’s antisocial behaviors (Dishion et al. 1995, 1996; Dodge et al. 2006; Dodge and Pettit 2003). This “deviancy training,” or reinforcement of antisocial behaviors, can contribute to gradual changes in attitudes towards antisocial behaviors (Dishion et al. 1996). Deviancy training can also include direct peer pressure to engage in specific delinquent behaviors, and the immediate effects of group pressure to conform may influence an adolescent’s choice to commit a specific crime (Warr 2002).

When examining co-offending, it is difficult to clarify which mechanism is exerting influence on delinquent behaviors. Through the deviancy training model, peer groups exert influence in general by shaping norms and providing peer pressure. However, an alternative explanation to peer involvement in delinquency is that peers directly influence behaviors through co-offending. Co-offending has been alternately viewed as the primary mechanism through which deviant peers exert influence, as just one type of peer influence, or as an entirely separate phenomenon that moderates the strength of other types of peer influence (McGloin and Piquero 2010; McGloin and Stickle 2011; Warr 2002; Weerman 2003; Zimring and Laqueur 2014). Co-offending may reflect the convenience of other peers being present when opportunity for criminal activity occurs, rather than a more pervasive psychological process. Deviant peers can be selected for co-offenses if they are perceived as being assets to criminal activities, or deviant peers can facilitate co-offending by providing additional settings or opportunities for delinquent behavior (McGloin and Piquero 2010; McGloin and Stickle 2011; Warr 2002; Weerman 2003). In some cases, co-offenses reflect processes associated more with a temporary “mob mentality” than with more stable changes in behavior (Warr 2002).

There is some evidence that the tendency to co-offend may vary across individual adolescents, with not all adolescents being equally likely to co-offend (Bijleveld and Hendriks 2003; Goldweber et al. 2011; McGloin and Stickle 2011). Co-offending is quite common among delinquent youth, significantly more so than among adult offenders (Carrington 2009; McGloin et al. 2008; Reiss 1986; Zimring and Laqueur 2014). However, while most adolescent crimes are committed in groups, a significant proportion of crimes are still committed by adolescents acting alone (Reiss and Farrington 1991; Stolzenberg and D’Alessio 2008; Piquero et al. 2007). Goldweber et al. (2011) found that while most adolescent offenders engaged in both solo and co-offending, three distinct groups emerged over time: a mixed-style offender trajectory (e.g., co-offending and solo offending), increasingly-solo offender trajectory (e.g., adolescents migrated from co-offending to solo offending), and exclusively-solo offending trajectory (e.g., only committed solo offenses). Given these different trajectories, it is important to examine how parental monitoring and association with deviant peers may differentially impact youth delinquency.

Continued questions persist regarding both the nature of co-offending generally and the potential moderating role of co-offending status on the relationship between peer delinquency and adolescent offending (McGloin and Stickle 2011). It may be that peer deviancy training processes (Dishion et al. 1995, 1996; Snyder et al. 2008) shape an adolescent’s perceptions of peer norms and by extension their own norms, but do not influence an adolescent’s likelihood to co-offend. On the other hand, adolescents who co-offend may be more strongly influenced by deviant peer norms, as co-offending peers’ deviant talk or peer pressure are more immediate to the criminal act itself. Further, it is possible that the tendency to co-offend may be associated with differential effects of parental monitoring, at least to the degree that the relation between parental monitoring and delinquency is mediated by its effects on deviant peer affiliation (Patterson and Dishion 1985; Patterson et al. 1989, 1992, 2000). To the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined whether co-offending moderates the mediational model of parental monitoring influencing delinquency via affiliation with deviant peers.

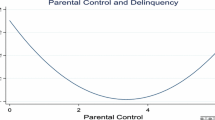

The current study uses a moderated-mediation analysis to examine how the tendency to co-offend might enhance the influence of deviant peers, within Patterson’s established model of deviant peers mediating the effects of parental monitoring on delinquency. Using a sample of juvenile offenders, we explored whether tendency to offend with peers versus alone moderated either pathway within the mediation model, allowing us to examine the relation between these important constructs. We predicted that tendency to co-offend would be associated with differences in the strength of peer influence, wherein there would be a weaker relationship between affiliation with deviant peers and delinquency for youth who do not co-offend (see Fig. 1). We also predicted that co-offending status would not likely moderate the pathway between parental monitoring and peer deviancy, given little empirical evidence to suggest this moderation. Nonetheless, this moderation was evaluated in exploratory analyses.

Method

Participants

As part of a larger project on adolescent substance use and delinquency, a 128-item self-report measure was administered to adolescents involved in the juvenile justice system serving a small-sized Midwestern city and the surrounding county. Participants were recruited from various settings within the juvenile justice system, ranging from youth currently on probation to youth involved in both a short-term detention facility and a long-term residential treatment facility. By recruiting from different settings in the juvenile justice system, a representative sample of the many court-involved youth was obtained. Research staff were contacted by court personnel when new adjudicated youth were processed and arrived to the detention center or treatment facility, in order for researchers to come in contact with the youth and/or their parent(s) shortly after their arrival to either facility. Youth recruited from the detention center were detained for 1 day to 3 weeks while awaiting sentencing (mean length of stay = 8.1 days). Youth who recruited from the residential treatment facility were sentenced to a 6 month stay in order to receive mental health rehabilitative services instead of incarceration.

A total of 192 adolescents participated. Six youth were excluded from analyses because the researcher administering the survey believed they were not responding honestly (i.e., went back and changed answers to appear more socially acceptable). Of the 186 valid surveys gathered, 86 youth were currently detained, 43 were participating in a residential youth treatment program, 4 were participants in a diversion program, and 53 were on probation at the time of interview. The racial/ethnic breakdown of the sample is as follows: 64.5 % African American, 15.1 % Caucasian, 3.2 % Latino/a or Hispanic, 12.4 % Multiracial, 1.1 % Native American, and 3.2 % “Other”. The sample was 90.9 % male, with mean age of 15.9 (Range = 12–18; SD = 1.22).

Procedure

After final approval of the project by the Institutional Review Board at the authors’ institution, a Certificate of Confidentiality from the US Department of Health and Human Services was obtained in order to safeguard the confidentiality of this vulnerable group of adolescents. The purpose and functions of the Certificate of Confidentiality was explained to both parents and adolescents before consent/assent was obtained. Written active consent was sought from parents either at the detention center before bi-weekly visitation, upon intake in the long-term residential treatment facility, or during meetings with their child’s probation officer. Adolescents were then approached, and provided both oral and written assent to participate.

Measures

Self-Reported Delinquency

Self-reported delinquency was assessed using an 18-item measure from the first wave of the National Youth Survey (Elliott 1976; M = 30.38, SD = 26.62, Cronbach’s α = .91). Items are answered on a nine-point Likert scale ranging from Never = 0, One to Two Times a Year = 1, Once every 2-3 months = 2, to 2-3 times a day = 8. Items begin with the phrase “During the past year, how many times have you…” and end with the item. Sample items include “…stolen or tried to steal money or something worth $100 or more?”, “…threatened someone with a weapon?”, and “…been involved in gang fights?” Detained youth were instructed to report on the 12 months immediately preceding their detention. Total self-reported delinquency was calculated by adding together the frequency score for each item endorsed and was treated as a continuous variable. Additionally, participants were asked what their most recent offense was that brought them into contact with the court system.

Parental Monitoring

Parental monitoring was evaluated using a nine-item measure previously used with at-risk youth (Tompsett and Toro 2010; M = 21.99, SD = 8.56, Cronbach’s α = .87). Items assess adolescents’ perceptions of their parents’ efforts to monitor their whereabouts, activities, and who they spend their time with (Tompsett and Toro 2010). Items are answered on a five-point Likert scale ranging from Never to Always. Sample items include “On a day-to-day basis, how often do your parent(s) know where you are?” and “How often do you tell your parent(s) who you are going to be with before you go out?” Items were averaged to obtain an overall value for parental monitoring.

Peer Delinquency

Peer delinquency and substance use was assessed using a 14-item measure evaluating the behavior of the respondent’s friends within the past 6 months (M = 27.94, SD = 12.37, Cronbach’s α = .92). This measure was developed for the Pittsburgh Youth Study (Stouthamer-Loeber et al. 2002), and was designed to be congruent with the self-reported delinquency scale also used in this study. Items are answered on a five-point Likert scale ranging from All of them to None of them with a Don’t know response option. Items begin with the phrase, “During the past six months, how many of your friends have…” and end with the item. Sample items include, “Skipped school without an excuse?” and “Gone into or tried to go into a building to steal something?” Detained youth were instructed to report on the 6 months immediately preceding their detention. Items were summed to obtain total peer delinquency.

Solo Versus Group Offending

One item was used to assess whether youth commit crimes alone or with friends, stating “When you are doing things that are illegal or could get you in trouble, how often are you doing them with friends?” Response options include “Never,” “Some of the time,” “Most of the time,” and “Always.” For analyses, this item was dichotomized to reflect youth who report never offending with friends (n = 27), versus youth who report offending with friends regardless of frequency (n = 159). In our sample, 14.5 % of participants indicated that they “never” offended with friends, while the remaining 85.5 % indicated that they offended with friends “Some of the time,” “Most of the time,” or “Always.”

Data Analyses

Descriptive analyses were run to explore differences between adolescents who tend to commit crimes with friends and those who do not, as well as to identify demographic covariates associated with main study variables. The PROCESS macro for SPSS designed by Hayes (2013) was used to test the initial simple mediation model. The macro uses bootstrapping to estimate confidence intervals for the indirect effect of parental monitoring on delinquency through friend deviance. This approach for testing mediation has several advantages over the Baron and Kenny (1986) method, including that bootstrapping removes the necessity of having a normal distribution for the indirect effect ab, and confidence intervals are provided to address any possible concerns about power [see Preacher and Hayes (2008) and Hayes (2013) for more information]. Two moderated mediation models were then tested using the same PROCESS macro, or what Hayes (2013) refers to as “conditional process analysis.” The first model tested our hypothesis that tendency to offend with friends would moderate the association between friend deviance and self-reported delinquency. The second model explored an alternative hypothesis, that tendency to offend with friends could moderate the relationship between parental monitoring and friend deviance.

Results

The tendency to offend alone or with peers was assessed using a single item, “When you are doing things that are illegal or could get you in trouble, how often are you doing them with friends?” A minority of respondents endorsed Never (n = 27, 14.5 %), with most respondents reporting Some of the time (n = 78, 41.9 %) or Most of the time (n = 49, 26.3 %), and fewer endorsing Always (n = 32, 17.2 %). Respondents who tended to offend with friends reported higher mean levels of overall delinquency (M = 32.76 vs. 14.74 who tended to offend alone; t(184) = −3.39, p < .01). Respondents also endorsed which of several common charges they had been charged with for their most recent court involvement; Chi square analyses revealed that respondents who tended to offend alone were less likely to have recently been charged with assault, robbery, burglary, weapons-related offenses, drug-related offenses, and gang-related violence. Respondents who tended to offend with friends were older (M = 15.97 vs. M = 15.44 who tended to offend alone, t(183) = −2.10, p < .05), but groups did not differ by gender or race. In addition, respondents who tended to offend with friends reported lower parental monitoring (M = 2.33 vs. M = 3.18, t(184) = 4.51, p < .001), and greater friend deviance (M = 24.95 vs. M = 16.88, t(182) = −2.90, p < .01).

Bivariate correlations between age, gender, and the main study variables were conducted to identify potential covariates (see Table 1 for correlations, means and standard deviations). Age was not correlated with self-reported delinquency, but was associated with less parental monitoring and more peer deviance. Age and Age2 did not associate with self-reported delinquency, indicating an age-crime curve was not present in our sample. Gender was associated only with parental monitoring, with females reporting greater parental monitoring. Analyses of variance were used to test for ethnic differences in variables of interest, and no significant differences emerged. Because age, gender, and ethnicity were not associated with the outcome of interest, demographic variables were not included as covariates in subsequent moderated mediation models.

The PROCESS macro for SPSS macros designed by Hayes (2013) was used to test whether affiliation with deviant peers mediated the effects of parental monitoring on self-reported delinquency. Results are reported in Table 2. The overall model accounted for significant variance in self-reported delinquency, with R 2 = .4640, F(2,181) = 78.36, p < .001. As expected, parental monitoring was significantly negatively associated with peer delinquency. Likewise, friend delinquency was significantly positively associated with self-reported delinquency. In support of the simple mediational model, a significant indirect effect of parental monitoring on self-reported delinquency through peer delinquency was found. Bootstrapping with 5000 samples supported this indirect effect, confirming that the pathways predicted by Patterson’s model of parental influence on delinquency were replicated in the current sample (Patterson et al. 1989).

The first moderated mediation model used the PROCESS macro to test whether tendency to offend with peers moderated path “b” in Fig. 1, the association between peer delinquency and self-reported delinquency (Model 14 from Hayes 2013). The model accounted for significant variance explained in self-reported delinquency, with R 2 = .4937, F(4,179) = 43.63, p < .001. The interaction term between tendency to offend with peers and peer delinquency was significant, indicating that the effect of friend delinquency on self-reported delinquency was moderated by tendency to offend with peers (b = .864, SE = .277, p < .01, CI 95 % = .317, 1.41). Conditional indirect effects are reported in Table 3, and demonstrate that the association between friend deviance and self-reported delinquency is stronger for adolescents who reported that they typically offend with peers. The association between peer deviance and adolescents’ own delinquency was no longer significant for adolescents who reported that they did not offend with peers. Exploratory analyses examined whether tendency to co-offend also moderated the association between parental monitoring and friend deviance, path “a” in Fig. 1 (Model 7 from Hayes 2013). The interaction term was non-significant (b = .353, SE = 3.630, p = .92, CI 95 % = −6.810, 7.516), demonstrating that the strength of the association between parental monitoring and friend deviance did not vary based on tendency to co-offend.

Discussion

Parental monitoring and deviant peers influence an adolescent’s engagement in delinquent behaviors (Keijsers et al. 2009; Kerr and Stattin 2000; Warr 2005). The current study used an adjudicated sample of youth to examine how the tendency to co-offend might enhance the influence of deviant peers, within Patterson’s established delinquency development model of deviant peers mediating the effects of parental monitoring on delinquency (Patterson and Dishion 1985; Patterson et al. 1989, 2000). Results demonstrated a significant indirect effect of parental monitoring on self-reported delinquency through peer delinquency, with a stronger relationship between peer delinquency and self-reported delinquency found for adolescents who tend to commit crimes with peers.

Parental monitoring can influence delinquency by limiting adolescents’ opportunities to engage in unsupervised activities, and at the same time, indirectly influencing delinquency through limiting affiliation with deviant peers (Patterson and Dishion 1985; Patterson et al. 1989, 2000). A significant indirect effect of parental monitoring on self-reported delinquency through peer delinquency was found, replicating the well-established model that deviant peers mediate the relationship between parental monitoring and youth delinquency (Ary et al. 1999; Patterson and Dishion 1985; Patterson et al. 1989, 1992, 2000). Parents who lack knowledge of their children’s whereabouts, activities, and acquaintances have children who are more likely to affiliate with delinquent peers, as well as to engage in delinquent behaviors themselves (Crouter and Head 2002; Dishion and McMahon 1998; Laird et al. 2003; Véronneau and Dishion 2010). Replicating this established finding supports the use of the current sample to explore nuances of Patterson’s model, including the effects of co-offending.

Descriptive differences were found between the groups of adolescents who reported that they never offended with friends versus those who reported co-offending. Adolescents who tend to offend with friends were older and reported higher mean levels of overall delinquency. These results are consistent with previous research which has demonstrated that solo-offenders tend to report less offending (Goldweber et al. 2011) compared to mixed-style offenders. The current finding that older adolescents were more likely to co-offend contrasts with previous findings that co-offending decreases over adolescence, or that solo-offending remains more common than co-offending across adolescence (Goldweber et al. 2011; Zimring and Laqueur 2014). Future research may clarify the nature of developmental trends in co-offending in adolescence. Together these results suggest that solo-offenders may be more autonomous from their peers in general, but that they also may have lower rates of other risk factors for delinquent behaviors as well.

The primary goal of this study was to examine the interaction between tendency to co-offend and the influence of deviant peer behaviors in general, within the context of the delinquency development mediational model of parental monitoring and deviant peers. The relationship between an adolescent’s perceptions of his/her peers’ delinquent behaviors and his/her own self-reported delinquency was significantly stronger for those adolescents who tended to offend together with friends. The relationship between peer and self-reported delinquency no longer was significant for adolescents who offend alone. Indeed, several key theoretical works recognize that oftentimes crime is a collective behavior (Sutherland 1947) and studies that recognize these points demonstrate the important impact co-offending patterns can have on offending pathways (McGloin and Piquero 2010). Warr (2002) suggests that the modal nature of group offending during adolescence reflects, at least in part, the potency of peer influence during this developmental phase. For instance, group offending may reflect the fact that deviant peers provide access to learning environments conducive to delinquency (see Akers 1998; Sutherland 1947) where adolescents can learn the attitudes, techniques, and motives for problem behaviors through interactions with their fellow peers (Akers 1998; Sutherland 1947). Deviant peers provide social reinforcement for antisocial behaviors through antisocial talk and verbally approving each other’s antisocial behaviors (Dishion et al. 1995, 1996; Dodge et al. 2006; Dodge and Pettit 2003). This antisocial talk may be more influential when adolescents offend in groups, as the social reinforcement is more immediate to the criminal act (McGloin and Stickle 2011). It is also possible that through co-offending, witnessing peers’ actual delinquent behaviors allows confirmation of peers’ attitudes regarding delinquent behavior, thereby strengthening the influence that peers have on co-offenders. At the same time, as co-offenders tend to change accomplices frequently, adolescents who tend to co-offend may also be exposed to a greater number or variety of deviant peers (Warr 1996), strengthening their potential influence. The current study did not find that co-offending moderated the association between parental monitoring and affiliation with deviant peers. Parental monitoring does appear to function, at least in part, by controlling access to deviant peers, as youth with higher levels of parental monitoring reported lower peer deviance and less likelihood of co-offending. However, there is little reason to expect that the dynamics of parent influence would be different for youth who tend to co-offend.

Strengths and Limitations

A number of limitations are important to note in interpreting the results of the present study. First and foremost, our study utilized a cross-sectional methodological design. It is not possible to infer a causal relationship between variable based on our results alone, though our mediational findings do parallel those found with longitudinal designs (Ary et al. 1999; Henry et al. 2001; Patterson et al. 1992). The delinquency measure refers to a broader time period than the peer delinquency measure, while the parental monitoring and co-offending items elicit more general impressions rather than a specific time frame. The current findings lend support for the importance of considering co-offending in future studies of the relationships between parents and peers in predicting delinquency, but caution should be used in drawing more specific causal conclusions based on the current data.

Another limitation that deserves mention is the reliance on self-report measures. Some evidence suggests that self-reports of delinquency may in fact be more accurate than official reports or other measures (Hardt and Peterson-Hardt 1977; Thornberry and Krohn 2000). However, youth may not accurately perceive their friends’ delinquency, or their parents’ monitoring efforts. The results of the current study may be viewed in terms of a stepping stone on the path towards greater understanding of how co-offending interacts with parental monitoring and delinquent peers, but it is important to recognize that the current results are limited to adolescent perceptions of these constructs. Conducting multiple-informant studies of youth involved in the juvenile justice system can be particularly challenging, but future studies using multiple informants over multiple time points would provide more reliable support for the models tested here.

Despite these limitations the current study has a number of strengths. Using a sample comprised entirely of delinquent youth is relatively rare within the literature on parent and peer influences on problem behaviors. By utilizing a sample of delinquent youth, we are able to paint a more accurate picture of peer influences among youth who are responsible for a significant portion of criminal activities. At the same time, the current sample included a wide range of rates of offending, including some youth who have engaged in delinquent behaviors quite infrequently. Our findings introduce the importance of considering a youth’s co-offending status within the Patterson’s delinquency development model, which could influence future investigations of this mediational model.

Implications and Future Directions

The current study highlights the importance of co-offending on the relationship between a youth’s self-reported delinquency and the reported delinquency of their peers. Although poor parental monitoring increases an adolescent’s access and association with deviant peers, thereby increasing youth’s own delinquency (Patterson and Dishion 1985; Patterson et al. 1989, 2000), the current study found that the association between peer delinquency and the youth’s own delinquency was moderated by their tendency to co-offend. Researchers in the field of criminology have long suggested the influential importance of co-offending and criminal accomplices in the development of delinquency (Akers 1998; McGloin and Piquero 2010; Warr 2002; Sutherland 1947). Many scholars root their initial thoughts of co-offending in Sutherland’s (1947) discussion of tutelage in that criminal accomplices influenced deviance both in form and frequency (McGloin and Piquero 2010; Warr 2002). In order to enhance the theoretical fields of criminology and psychology, it is imperative that researchers make a distinction between reporting having deviant peers, co-offending with other non-friend accomplices, and co-offending with delinquent friends. When youth have peers with deviant values, these values are likely to be more influential if the youth directly experiences his or her peers engaging in delinquent behaviors through co-offending. To better understand how peers influence delinquency, whether youth offend with others and with whom they offend with should be taken into account.

These results have implications for practitioners working with delinquent youth. Namely, practitioners should be aware that adolescents who commit crimes alone appear to be less influenced by their friends’ delinquency and have higher parental monitoring. That being said, typical predictors of offending (e.g., asking youth about their friends’ risky behaviors and asking parents about their monitoring) may not be sufficient to identify youth who offend on their own. Future research should identify other risk factors for solo offending to best assess and treat this sub-sample of delinquent youth. Conversely, adolescents who co-offend demonstrate a number of additional risk factors, including lower parental monitoring and greater overall delinquency. For these youth, earlier interventions should continue to focus on building positive peer relationships and ways to mitigate the possible pressures of deviant peers.

References

Akers, R. L. (1998). Social learning and social structure: A general theory of crime and deviance. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press.

Ary, D. V., Duncan, T. E., Duncan, S. C., & Hops, H. (1999). Adolescent problem behavior: The influence of parents and peers. Behavior Research and Therapy, 37, 217–230. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00133-8.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173.

Bauman, K. E., & Ennett, S. T. (1996). On the importance of peer influence for adolescent drug use: Commonly neglected considerations. Addiction, 91(2), 185–198. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.9121852.x.

Bijleveld, C., & Hendriks, J. (2003). Juvenile sex offenders: Differences between group and solo offenders. Psychology, Crime & Law, 9(3), 237–245. doi:10.1080/1068316021000030568.

Bowman, M. A., Prelow, H. M., & Weaver, S. R. (2007). Parenting behaviors, association with deviant peers, and delinquency in African American adolescents: A mediated-moderation model. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(4), 517–527.

Carrington, P. J. (2009). Co-offending and the development of the delinquent career. Criminology, 47, 1295–1329. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00176.x.

Crouter, A. C., & Head, M. R. (2002). Parental monitoring and knowledge of children. In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting, 2nd ed., vol. 3: Becoming and being a parent (pp. 461–483). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Dishion, T. J., Andrews, D. W., & Crosby, L. (1995). Adolescent boys and their friends in early adolescence: Relationship characteristics, quality, and interactional processes. Child Development, 66, 139–151. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00861.x.

Dishion, T. J., & McMahon, R. J. (1998). Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1, 61–75.

Dishion, T. J., Patterson, G. R., Stoolmiller, M., & Skinner, M. I. (1991). Family, school and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology, 27, 172–180.

Dishion, T. J., Spracklen, K. M., Andrews, D. W., & Patterson, G. R. (1996). Deviancy training in male adolescent friendships. Behavior Therapy, 27(3), 373–390.

Dodge, K. A., Dishion, T. J., & Lansford, J. E. (2006). Deviant peer influence in programs for youth: Problems and solutions. New York: Guilford Press.

Dodge, K. A., & Pettit, G. S. (2003). A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 39, 349–371.

Elliott, D. National Youth Survey [United States]: Wave I, 1976 [Computer File]. ICPSR08375-v2. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university. Bibliographic Citation: Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2008-08-01. doi:10.3886/ICPSR08375.

Elliott, D. S., & Menard, S. (1996). Delinquent friends and delinquent behavior: Temporal and developmental patterns. In J. David Hawkins (Ed.), Delinquency and crime: Current theories (pp. 28–67). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Goldweber, A., Dmitrieva, J., Cauffman, E., Piquero, A. R., & Steinberg, L. (2011). The development of criminal style in adolescence and young adulthood: Separating the lemmings from the loners. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(3), 332–346. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9534-5.

Hardt, R. H., & Peterson-Hardt, S. (1977). On determining the quality of the delinquency self-report method. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 14(2), 247–259.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis a regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

Henry, D. B., Tolan, P. H., & Gorman-Smith, D. (2001). Longitudinal family and peer group effects on violence and nonviolent delinquency. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(2), 172–186.

Keijsers, L., Branje, S., Hawk, S. T., Schwartz, S. J., Frijns, T., Koot, H. M., … & Meeus, W. (2011). Forbidden friends as forbidden fruit: Parental supervision of friendships, contact with deviant peers, and adolescent delinquency: Parental supervision of peer relationships. Child Development, no–no. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01701.x

Keijsers, L., Frijns, T., Branje, S. J., & Meeus, W. (2009). Developmental links of adolescent disclosure, parental solicitation, and control with delinquency: Moderation by parental support. Developmental Psychology, 45(5), 1314–1327. doi:10.1037/a0016693.

Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2000). What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology, 36(3), 366–380. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.36.3.366.

Kerr, M., Stattin, H., & Burk, W. J. (2010). A reinterpretation of parental monitoring in longitudinal perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(1), 39–64.

Lahey, B. B., Van Hulle, C. A., D’Onofrio, B. M., Rodgers, J. L., & Waldman, I. D. (2008). Is parental knowledge of their adolescent offspring’s whereabouts and peer associations spuriously associated with offspring delinquency? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 807–823.

Laird, R. D., Pettit, G. S., Bates, J. E., & Dodge, K. A. (2003). Parents’ monitoring-relevant knowledge and adolescents’ delinquent behavior: Evidence of correlated developmental changes and reciprocal influences. Child Development, 74(3), 752–768.

McGloin, J. M., & Piquero, A. R. (2010). On the relationship between co-offending network redundancy and offending versatility. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 47, 63–90.

McGloin, J. M., & Stickle, W. P. (2011). Influence or convenience? Disentangling peer influence and co-offending for chronic offenders. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 48, 419–447.

McGloin, J. M., Sullivan, C. J., Piquero, A. R., & Bacon, S. (2008). Investigating the stability of co-offending and co-offenders among a sample of youthful offenders. Criminology, 46, 155–188.

Mounts, N. S. (2008). Linkages between parenting and peer relationships: A model for parental management of adolescents peer relationships. In M. Kerr, H. Stattin, & R. Engels (Eds.), What can parents do: New insights into the role of parents in adolescent problem behaviour (pp. 163–189). West Sussex: Wiley.

Patterson, G. R., DeBaryshe, B. D., & Ramsey, E. (1989). A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist, 44, 329–335. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.44.2.329.

Patterson, G. R., & Dishion, T. J. (1985). Contributions of families and peers to delinquency. Criminology, 23(1), 63–79.

Patterson, G. R., Dishion, T. J., & Yoerger, K. (2000). Adolescent growth in new forms of problem behavior: Macro-and micro-peer dynamics. Prevention Science, 1(1), 3–13.

Patterson, G. R., Reid, J. B., & Dishion, T. J. (1992). Antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia.

Patterson, G. R., & Yoerger, K. (1997). A developmental model for late-onset delinquency. In D. W. Osgood & J. McCord (Eds.), Motivation and delinquency (Vol. 44, pp. 119–177). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P., & Blumstein, A. (2007). Key issues in criminal career research: New analyses of the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling methods for estimating and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Reiss, A. J. (1986). Co-offender influences on criminal careers. Criminal Careers and Career Criminals, 2, 121–160.

Reiss, A. J., & Farrington, D. P. (1991). Advancing knowledge about co-offending: Results from a prospective longitudinal survey of London males. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 82, 360–395.

Simons, R. L., Whitbeck, L. B., & Wu, C. (1994a). Resilient and vulnerable adolescents (pp. 223–234). Families in troubled times: Adapting to change in rural America.

Simons, R. L., Wu, C., Conger, R. D., & Lorenz, F. O. (1994b). Two routes to delinquency: Differences between early and late starters in the impact of parenting and deviant peers. Criminology, 32, 247–276.

Snyder, J., Schrepferman, L., McEachern, A., Barner, S., Johnson, K., & Provines, J. (2008). Peer deviancy training and peer coercion: Dual processes associated with early-onset conduct problems. Child Development, 79, 252–268.

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71, 1072–1085.

Stolzenberg, L., & D’Alessio, S. J. (2008). Co-offending and the age-crime curve. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 45(1), 65–86. doi:10.1177/0022427807309441.

Stouthamer-Loeber, M., Loeber, R., Wei, E., Farrington, D. P., & Wistrom, P. H. (2002). Risk and promotive effects in the explanation of persistent serious delinquency in boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 111–123.

Sutherland, E. H. (1947). Principles of criminology (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott.

Thornberry, T. P., & Krohn, M. D. (2000). The self-report method for measuring delinquency and crime. Criminal Justice, 4(1), 33–83.

Tilton-Weaver, L. C., Burk, W. J., Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2013). Can parental monitoring and peer management reduce the selection or influence of delinquent peers? Testing the question using a dynamic social network approach. Developmental Psychology, 49(11), 2057–2070. doi:10.1037/a0031854.

Tompsett, C. J., & Toro, P. A. (2010). Predicting overt and covert antisocial behaviors: Parents, peers, and homelessness. Journal of Community Psychology, 38, 469–485.

Véronneau, M. H., & Dishion, T. J. (2010). Predicting change in early adolescent problem behavior in the middle school years: A mesosystemic perspective on parenting and peer experiences. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 1125–1137.

Warr, M. (1996). Organization and instigation in delinquent groups. Criminology, 34(1), 11–37.

Warr, M. (2002). Companions in crime: The social aspects of criminal conduct. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Warr, M. (2005). Making delinquent friends: Adult supervision and children’s affiliations. Criminology, 43, 77–106.

Weerman, F. M. (2003). Co-offending as social exchange: Explaining characteristics of co-offending. British Journal of Criminology, 43, 398–416.

Weerman, F. M. (2004). The changing role of delinquent peers in childhood and adolescence: Issues, findings and puzzles. In G. Bruinsma, H. Elffers, & J. W. de Keijser (Eds.), Punishment, places and perpetrators: Developments in criminology and criminal justice research (pp. 279–297). Portland, OR: Willan Publishing.

Zimring, F. E., & Laqueur, H. (2014). Kids, groups, and crime in defense of conventional wisdom. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. doi:10.1177/0022427814555770.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Center for Family and Demographic Research, Bowling Green State University, which has core funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24HD050959-07).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dynes, M.E., Domoff, S.E., Hassan, S. et al. The Influence of Co-offending Within a Moderated Mediation Model of Parent and Peer Predictors of Delinquency. J Child Fam Stud 24, 3516–3525 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0153-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0153-3