Abstract

Parents face many questions, uncertainties, and fears at the time children are diagnosed with autism. At the heart of this process is the relationship with early interventionists who work early on and intimately with families to help children with autism learn, connect, and engage. This chapter describes a series of early intervention strategies to promote a coaching (versus expert-driven) relationship between interventionists and families. The approach, procedures, and examples come from our own line of research and work coaching families with the Early Start Denver Model (Rogers, Dawson, & Vismara, 2012) as we talk about how to define and address child learning goals inside everyday routine-based activities and how to increase parents’ motivation when it comes to making the change necessary to address goals. The outcome is a stronger working alliance to guide, support, and ultimately empower parents toward active learning and child-family engagement.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Autism

- Early intervention

- Parent coaching

- Parent implementation

- Early Start Denver Model

- Family-centered planning

- Motivational interviewing

- Parental stress

Introduction

As methods for infant/toddler autism identification evolve and improve, and ever-younger children are being referred to early intervention, a dilemma is arising for interventionists. We know that infant-toddler development is profoundly influenced by characteristics of parent-child interaction. Young typically developing children spend their waking hours (approximately 70 h per week!) interacting with the people and objects in their everyday lives, and developmentalists assume that this level of engagement is needed in order to foster typical social communicative development. Thus, the oft-cited recommendation that young children with autism need at least 25 h per week of active social engagement in organized, developmentally appropriate activities that are interesting and meaningful to them (National Research Council, 2001) reflects a “dosage” far less than that occurring in the lives of typically developing young children in adequate learning environments.

However, too often early intervention for autism is equated with 1:1 structured interactions with a trained adult delivering clinician-generated treatment plans and procedures for many hours daily, thus replacing parent/caregiver-child interaction times with scheduled child-therapist interaction and replacing opportunities for engagement in everyday activities with adult- structured and adult-designed learning activities. Furthermore, scheduling 15–25 h of clinician-delivered treatment in between a young child’s sleep and care schedules by necessity replaces parent-child interaction times in everyday activities.

There are two potentially damaging messages to parents embedded in the intensive therapist delivery approach. The first is that time with (often paraprofessional) therapists is more important for child learning than time with parents and family. The second is that “adult-directed therapy” involving highly specified and preplanned lessons is the only way their child can learn and is thus more important than learning opportunities within ongoing family activities. Such messages implicitly assume the lack of parental competence to provide for child needs and undercut parents’ confidence in their parenting and their ability to help their child thrive. When these messages are delivered at the start of a young child’s life, they can set in motion a lifelong assumption that the child with autism’s treatment needs will always be best served outside the family, creating a dependence on others that may last a very long time.

There is another way. At the point of a young child’s diagnosis, most parents will ask the diagnostician, “What can we do to help our child?” Instead of responding with a recommendation that parents should enroll their child in 25 or more hours a week of behavioral therapy, we can focus on the parents’ goals and the learning needs and styles of the child and think with the family about the many ways that the family as well as others in the child’s life can be brought together to meet these needs. Including the parent and family interactions as one of the critical “interventions” for the young child reflects parent expectations that they will provide their child’s care.

Instead of replacing parents with therapists as young children’s primary teachers, this chapter will describe early intervention strategies for autism that embrace parents as central players; that work from a family-centered , rather than child-centered perspective; and that develop strong working alliances that support active family engagement in defining and addressing child learning goals inside parent-child activities and interactions in everyday routine-based activities.

In the first part of the chapter, we will describe some procedures that we have found to help families engage with the early intervention provider, clinician, or interventionist in a particular type of relationship – a coaching relationship (Hanft, Rush, & Shelden, 2004). The coaching relationship begins at the first point of contact with the family in the goal setting process and contributes to a strong alliance with the interventionist so that all can work together to create a set of treatment objectives that address children’s learning needs across environments. Principles for coaching, examples of the process unfolding with families, and a format for using coaching in sessions with parents and children will be shared from the coaching principles, approach, and philosophy of the parent-implemented Early Start Denver Model (P-ESDM; Rogers et al., 2012).

In the second part of the chapter, we will describe procedures for supporting families to embed treatment objectives into everyday activities at home. One process involves helping families identify the settings and range of learning opportunities that already exist in the daily routines, rituals, and moments that parents and young children spend together. A second process that supports families recognizes the unique challenges and strengths of their own family in raising their child with autism and supporting their individual child’s learning.

Finally, we will end by describing a particular method for working with family motivation to make the changes needed to address their goals for their child in everyday routines. The procedures and approaches we describe come from our work over the past 10 years in supporting parents to use techniques from the ESDM (Rogers & Dawson, 2010) at home, supported by a foundation of clinical experience and empirical data, from our own work and from others.

Defining a Family-Centered Approach

Early intervention models for autism were originally developed for children between 3 and 5 years of age, and several different intervention approaches have demonstrated efficacy in improving preschoolers’ social-communicative and cognitive development. However, preschool-aged children have very different needs and capabilities than those younger than 3. Infants and toddlers need to sleep and eat frequently, need considerable physical and emotional care, and require a great deal of adult attention and interaction. The long-term dependency that human infants and toddlers have on adults is believed to be an important mechanism for developing the advanced communication and cognitive abilities that we have as a species. Infant-toddler developmental progress is dependent on the language and actions used by parents and the meanings that are associated with the socially charged routines, rituals, and activities that make up each and every day. And families expect to have ongoing interaction with infants and toddlers, even more so than with their preschoolers and older children, who can do much more for themselves. Helping parents to interact and communicate based on engagement and learning strategies developed for infants and toddlers therefore becomes important to promoting the long-term development of social-communicative skills and brain functioning affected by early autism (Dawson et al., 2012). The quality of parent–child interaction is a crucial component of long-term change (Anderson, Rosalind, Lord, & Welch, 2009; Lord, Luyster, Guthrie, & Pickles, 2012). For all these reasons, parents are key members of a young child’s treatment team. However, parents have a unique perspective, investment, and responsibility about their child’s care. Their unique role requires that their participation in their child’s learning be defined by them and that their relationship with interventionists whom they have asked to help needs to evolve to fit their goals for seeking help. Thus, the intervention focus for the youngest children with autism expands from the child alone to the child in interaction with parents and other family members – a family-centered approach that recognizes the centrality of family life and learning for young children with autism. And this intervention focus also requires a shift away from directly eliciting specific skills in the child and instead supporting parents to use strategies that will promote specific child learning goals inside everyday activities.

However, parents are not students. They are consumers of intervention services. They have choices about clinicians, and they have choices about what they will do and not do with their child in everyday life. They approach an interventionist asking for specific help, and the type of response they receive, both in the moment and over time, will determine how successful, and how long-lasting, the shared work will be.

What kind of relationship will be most helpful in supporting the parents to determine and achieve their goals for their child? Hanft et al. (2004) have made an excellent argument for the utility of a coaching relationship between clinician and parent working together in early intervention. A coach is someone an adult seeks out from whom to learn something very specific. The adult (or parent in this case) articulates what he or she wants to learn (i.e., personal goals) and locates a coach to help him or her achieve the stated goals (i.e., a coaching plan). As the coaching continues, the adult gauges whether or not the relationship is helping to reach his or her goals (i.e., evaluation). If things feel successful and positive, the coaching continues, and if not, the adult may end the relationship and either go elsewhere for support or give up on the goal. Thus, in an adult learning framework, the adult seeks the coach’s skill in achieving personal goals, and the evaluation of the success of the relationship in moving toward goals determines the outcomes of the relationship.

Coaching shares certain characteristics with other approaches to helping adults, like counseling, mentoring, teaching, or supervising. All may include a one-to-one relationship with helping the adult access specialized expertise. The distinction though between coaching and these other types of relationships rests on the degree of responsibility between the adult and coach participating in the learning experience. Coaching aims to support the learner when, where, and how the support is needed. This is different from an expert-driven model where the information transfers from a master to a student. Coaching is an interactive process and builds on the learner’s ideas, experiences, skills, and knowledge to integrate new information and skills with current ones. In early intervention, the provider’s role as the “coach” is redefined from being an expert to being a resource to the parents in the development or refinement of their ability to use new and existing skills and information in ways that will meet their personal goals. The coaching relationship supports parents and other caregivers to (1) identify how to strengthen and enhance a child’s learning within existing, real-life situations and to (2) ensure that child learning happens as anticipated. The coaching plans for the intervention (i.e., what learning opportunities will occur, when and how they will happen, and who will be involved) evolve from a discussion with parents about the opportunities and demands of their daily life, their goals, and their current knowledge and skills integrated with the coach’s observation and assessment of the current situation and child and family needs. The coach explores with the parents how and when to use specific strategies and information to help their child participate and learn within meaningful family activities. It is a mutual conversation in which the coach and parents share and receive information, ideas, and feedback rather than one telling the other what to do.

Coaching Principles

In this adult learning relationship between parents and coach, each partner has resources to share and skills to gain from interacting with the other. The coach has information to share about child growth and development and specific intervention strategies to enhance this process. The parents and other caregivers have intimate knowledge of a child’s abilities, challenges, and typical performance in any situation. They understand the child’s and family’s daily routines, lifestyle, environments, family culture, and ideas for teachable moments and desirable goals they would like to accomplish for their child, themselves, and as a family. This exchange of ideas, experiences, methods, and resources between the coach and parents ensures that coaching does not become telling someone what to do and how to do it but rather remains a dialogue of joint learning and insight about new or expanded skills that can be used inside existing interactions to promote growth. One of the coach’s tasks is to keep the conversation between the coach and parents well-balanced.

Listening to the parents, the coach comes to understand their story and their perspective and expectations with the context of their daily life. The coach uses this information to find common ground between the parents’ beliefs and what they want to make happen and the resources that will help to meet their goals. The coach must also know when and how to share new information and ideas in a way that supports the parents in achieving mutually agreed-upon outcomes. Part of doing so involves the coach’s skills in quickly understanding both (1) what information, ideas, and skills may be useful to this set of parents and also (2) how these can be integrated into the parents’ current knowledge, skills, values, and priorities.

Clearly, then, the coach’s role is not didactically telling or showing the parents what they should or should not be doing. An effective coach supports the parents to examine their ideas and experiences so as to promote self-discovery while sharing his or her own knowledge and skills as needed. The coach and parent sessions focus on exploring, sharing, and testing of ideas supported by the coach’s skills in listening, asking the right questions, observing ongoing interactions, and supplementing this with their own knowledge base in order to build parents’ capacity to identify and implement strategies and/or solutions to help the child in learning goals that they have prioritized.

Also important to the coaching relationship is the parents’ emotional experience with the coach. The coach demonstrates a caring, compassionate attitude through encouragement, patience, and creation of a safe environment for the parents to learn, to ask for help without feeling inept or ignorant, and to accept and learn from unsuccessful attempts that naturally occur in the learning process. The coach empathizes with challenges, experiences them himself or herself, and assists parents to reflect mistakes or failures in order to consider other options. It is a balanced, reciprocal relationship guided by a mutual understanding of values and with clear roles to encourage and support ideas for learning.

Supporting Parents in the Goal Setting Process

The first contact

In ESDM work, the diagnostic process is carefully separated from intervention work. Different teams, different spaces, different tools, and different questions define these activities. The intervention process begins with the first contact of the clinician or interventionist who will serve as a coach to the family. In the situation in which the diagnostician is also the interventionist, it is important to separate these activities in time and in type. The diagnostic process ends with a diagnostic discussion with parents and recommendations for the next steps. A dialogue about beginning intervention begins at a different time, in a different appointment, and in a different style.

The intervention/coaching relationship begins at the point at which parents ask, and the interventionist agrees, to “help them provide intervention for their child.” The wording is important here. A coaching interventionist does not agree to do the intervention but rather to help the parents provide the intervention. This wording, both the nature of the relationships and the nature of the early intervention approach, is delivered in the message that parents are capable and motivated to help their child, and the role of the coach as a parent helper rather than a child therapist is defined.

A helpful follow-up question leads directly to parent goals for child progress: “And what is it that you most want to teach your child? or “What would you most like to see your child accomplish in the next three months?” (The ESDM works in 12-week periods to write and achieve objectives; our examples in this chapter come from our work inside P-ESDM with families). Focusing on a reasonable period of time for progress, rather than the immediate “this week or today,” recognizes that learning and change take time, and we will be working toward a point in the short term, but not immediate future. While more data are needed before short-term learning objectives can be developed, asking parents their goals at the very beginning of the relationship emphasizes who is steering the ship – the parents as consumers – and it prioritizes their goals, not the interventionist’s goals. The parents are already in the driver’s seat. Taking down parent goals verbatim without offering changes, suggestions, or modifications delivers this message strongly.

What about parents who are unsure of what skills or goals to teach to their child? Coaches still want to refrain from telling parents what to do and instead opt for other strategies that will encourage parents’ reflection and to select goals. For example, the coach may ask the parent to describe a typical day with the child and in particular those behaviors, activities, or events that are more challenging to manage. Identifying child challenges helps lead the conversation to goals. Another option is for the coach to watch the parent carrying out a usual routine with the child, such as reading a book together or attempting to occupy the child with a toy to make a phone call. Once the routine ends, the coach can ask questions to help the parent identify the child skills that contributed to positive, enjoyable interactions and what other behaviors could extend or increase those moments. If involving the child is difficult or not possible to do, the coach and parent may act out scenarios to generate potential goals. Visualization, demonstrations, and role-play then create alternative techniques to parents maintaining their role as the leaders in the goal selection process.

The assessment phase

The next procedural step generally requires some type of assessment of child and family needs, strengths, and routines to specify reasonable short-term objectives, as well as to determine what supports the family needs to support their child. Maintaining parent involvement and engagement in the intervention process can be helped or hurt by how this assessment is managed. In our ESDM work, the treatment assessment is temporally, physically, and procedurally quite separate from any diagnostic assessment. The treatment assessment involves the parents, interventionist, and child together in the child’s home or in a clinic room setup as family-friendly as possible, on the floor, interacting across a series of typical toddler play and care tasks (e.g., snack time, changing diapers, dressing). The interventionist and parents are in ongoing dialogue about the child, what he or she likes, what he or she does with similar things at home, and what outcomes are important to achieve.

During the assessment, an ESDM coach orchestrates the various activities that get carried out for the assessment, though it is usually the parent who is primarily interacting with the child. This is because infants and toddlers typically prefer interacting with parents over strangers and because the parents know what the child is likely to do with the materials or activities. The interventionist uses the ESDM Curriculum Checklist, an itemized list of typical infancy through preschool-age skills (e.g., child responds to adult’s instruction without the use of gestures; see Rogers & Dawson, 2010 for more information), to gather data on the child’s developmental abilities and needs while suggesting and setting up various activities, observing the child and parents’ interaction in the different activities, adding various probes, suggesting variations to the parents, and orchestrating the hour in order to complete the checklist. Based on the parents’ preference for learning, the interventionist may suggest play ideas, model actions, hand over materials, and/or ask questions to effectively support the parents. The coach may certainly also initiate activities with the child but as a secondary person, not the main interactor. As the child finishes with one activity, child, parent, and interventionist transition to another type of activity that occurs in everyday life for them and often a change in location (e.g., floor to table, inside to outside, bathroom to kitchen). Activities, play, and dialogue continue until the interventionist has gathered all the data needed or until child needs dictate that the session ends. The assessment session provides a great deal of information about child skills and behavior in various settings from parent descriptions, from direct observation, and from conversation. Interactions with the child also reveal much about the strengths and needs that the parents experience in everyday life with their child. The interventionist needs to understand the daily routines of the family and child, how they go, and where the parent intervention priorities fall in terms of teachable moments and activities and problem moments and activities. The next appointment is scheduled with the parent to use the information collected from the first session that will define the short-term objectives and the family’s learning plan for the shared work of parents, interventionist, and child. Parents are asked about any additional goals they would like the intervention to focus on over the coming 12-week period, which the interventionist writes down, and they know that the next session will begin with a review and final agreements about the intervention plan for the next 12 weeks.

We have described a treatment assessment that is highly interactive and quite family-centered. When the assessment process is handled in this way, the parents and the interventionist are from the beginning working as partners to share information, learn from each other, and work with the child. The assessment requires active participation and engagement from both, and the interventionist and parents are in both a teaching and learner roles. In this way the assessment delivers the message of parental competence and knowledge and the need for therapist-parent partnership and coordination, necessary to accomplish intervention tasks.

Beginning treatment

In ESDM work, this next contact bridges from treatment-based assessment to intervention. The first treatment session begins with reviewing and agreeing on treatment objectives for the next 12 weeks. The interventionist shares with the parent a first draft of objectives based on the parents’ statements of their goals for their child as well as on ideas the interventionist has based on the child assessments. The objectives are written in parent-friendly language and typical ESDM structure, describing the everyday setting and activities within which certain skills will be practiced, the parent or environmental antecedent, the desired child behavior, and the criterion and generalization aspects for mastery. Parental agreement is sought for each objective. If the objective is not endorsed by the parents (e.g., toilet training, using a fork, self-dressing), the objective is removed from the list. Other objectives that may not seem important to parents in terms of daily life (e.g., symbolic play) are explained by the interventionist as foundations for critical, later emerging skills to help the parents understand their importance. Parental wishes for different materials, instructions, etc. are incorporated into the treatment plan, and once parent and interventionist agree on the treatment plan, the therapist creates a finalized list and writes a set of teaching steps for each objective that will take the child from current skill level to the skill specified in the objective and datasheet that captures the objectives and steps to be used in treatment sessions These are provided to the family at the next visit and are used and discussed in each session, so that parents see and experience the systematic approach to child learning used in ESDM.

Here is an example of a parent-friendly objective and steps to increase the child’s play skills, engagement, and ability to play back-and-forth with the parent no matter who initiates the play idea. Notice that a few toy ideas are suggested (from previous parent input) but not specified in this example. This is deliberate ESDM planning so that the parent and child are not restricted to a set list of activities but instead can use any type of toy or play-based material to work toward this goal and maximize the child’s ability to develop this skill.

When my child and I are playing with toys, he and I will take at least four back-and-forth turns to put in, take out, or do an action with the toy he or I choose for three or more different play activities (e.g., cars and racetrack, train puzzle, animal farm) each day for 1 week.

-

Step 1: Watches and stays with the activity when I hand him pieces or materials to take his turns for 2–3 activities each day.

-

Step 2: Watches and stays in the activity when I hand him pieces, and take at least one turn to copy his play actions for 2–3 activities each day.

-

Step 3: Watches and stays in the activity when I hand him pieces, and we take 3–4 back-and-forth turns to copy his play actions for three or more activities each day.

-

Step 4: Watches and stays in the activity when we take at least three back-and-forth turns to do my play actions for three or more activities each day.

-

Step 5: Watches and stays in the activity when we take at least four back-and-forth turns to do each other’s play actions for three or more activities each day.

The presence of already specified treatment objectives does not override the parents’ or interventionist’s ability to generate a new objective at any time during treatment sessions. New challenges or changes emerge that may require the alteration, elimination, or addition of other short-term objectives. As this occurs, the list of objectives is updated, so that the written treatment plan always defines what is actually being taught. In this section, we have described a way of handling the dialogue between parents and interventionist at the very start of treatment, one in which parents are highly engaged throughout the contacts and play a major role in the treatment assessment and setting of treatment goals. The parents maintain their authority as experts in their child’s needs and skills, in their family’s strengths and needs, and in their decision-making role. The interventionist joins them and learns a great deal about the family’s routines, priorities, and views, as well as the way that they play with, help, teach, care for, and communicate with their child. The interaction style and the process of developing the treatment plan represent two aspects of ESDM work with parents: “shared control” and partnerships with parents.

Coaching Parents in the Implementation of Child Goals

As parents put new learning into practice, the interventionist or coach provides feedback and observations, remaining focused on the parents’ goals, perspectives, and actions. Through the back-and-forth engagement, the coach comes to understand the parents’ preferred learning styles for processing information, problem-solving, and ongoing ability to put new knowledge into practice. The coach monitors parents’ understanding carefully, noting when additional information may be required to extend progress, how consistent new information is with what is already known, and what resources or examples may be drawn to further their understanding of a topic. The coach and parents then review together the outcomes from practiced actions compared to previous experiences. The coach offers and encourages the parents’ ideas of what steps to take that will help to build on current skills and promote ongoing learning and practice day by day. There evolves a respectful partnership and a supportive learning environment shaped by the parents, not imposed by the coach.

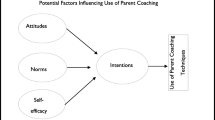

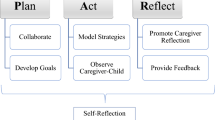

The coach has several methods to understand what parents know or understand about a particular topic, strategy, or goal before sharing new information and suggesting actions to try. Using observations, active listening, prompting, and questioning, the coach guides the parents through a process of self-discovery about what they already know, are doing, have tried, and think about in relation to a specific need or situation. This process is based on the researched practices of Hanft et al. (2004) following a process of planning, observation, coaching, reflection, and evaluation. The coach and parents move through each step not in a linear process but back and forth, in and out, as many times as necessary as needs and goals are determined, refined, and put into practice. The steps do not change the expectation for an equal, reciprocal relationship between the coach and parents but aim to strengthen the trust and respect already established and the learning that comes from the practice, reflection, and continued interaction of the coaching process.

Planning

Sometimes in coaching, the plan of what content to address with the parents may not be planned or selected ahead of the session but instead may come from the observations or conversations that occur from the parents’ and coach’s time together. For example, a parent may express to the coach more confidence and ability in using a teaching strategy following her practice since the last session. She may now let the coach know she now feels ready in the session to try the strategy in another context so as to expand the child’s behavior. The coach has to be ready to follow the parent in this direction and to respond with the coaching tools now to facilitate this next step in the learning process. In another unexpected moment, the coach hears the parent’s uncertainty in his description of how to follow the child’s play interests and imitate the child’s actions so as to keep her engaged longer in the activity. The coach has to put aside any of his or her goals for what the session might have addressed and instead focus on what the parent is expressing now as a pertinent need. In each example, the parent and coach may not have known what new information would come inside the session or how exactly the child would respond until tried. The parent’s response becomes a priority for the coach to now support in the existing session. Whether planned or spontaneous, both ways in which needs arise contribute information to understanding parents’ learning goals and the first step to developing an intervention plan for change. In turn this plan for change creates the agenda or focus of the session. It specifies the area in need of support and the goal(s) to follow for more appropriate, productive, and meaningful change. It also creates a clear outline for the subsequent coaching steps to reference as the rest of the intervention plan is developed. This check-in helps to ensure original goals are preserved and at an appropriate learning pace based on the parent-child response to the intervention. Example questions are suggested below to guide the conversation between the coach and parents in the discovery of learning goals to set the sessions.

Observation

Once a plan is set for the session, a period of observation follows. The coach can observe the parents in action with the goal(s), or the parents can observe the coach modeling some type of action, technique, or activity with the child and related to the goal. There is also the option for self-observation in which the parents consciously observe themselves during an activity or situation. The parents think about personal behaviors that could promote their effectiveness with the goal, another caretaker’s ability to meet the goal, or the child’s learning as a result of the implemented goal. For example, a parent may want the coach to observe how he followed the child’s lead while drawing with markers to support his goal of increasing the child’s communicative gestures and vocalizations. The coach observed the father creating opportunities to practice this goal through the use of choices to the child inside the preferred activity. The father asked the child which color marker she wanted and which picture on the paper to color. The father responded with the preferred item or action each time the child pointed or vocalized her choice. The father also created moments for the child to ask for help by giving her the marker to open or close the cap and pointing to other markers to use or pictures to color. From the observation, the coach acknowledges the father’s intervention skills to facilitate communicative opportunities from the child. The observation also allows the coach to make other suggestions of how to extend the activity if and when the child loses interest in coloring the pages. The coach helps the father think of other materials and actions that could be added to the activity, such as placing stickers on the paper, cutting out colored pictures, and drawing child-preferred pictures of animals.

In another example, the parent may ask for the coach’s assistance to meet her goal of reading books to her child. During the coach’s observation of the parent and child reading books, the child sat in the parent’s lap and did not listen to the story. The child did not look at the pictures pointed out by the parent and preferred to quickly turn the pages to the end of the book. The coach demonstrated different seated or standing options for the child, such as a chair, beanbag, or leaning against a table, so that the child’s attention from the very start of the book could be more primed to the parent’s language and actions. The parent observed the coach positioning her body to the child’s eye level and holding the book close to her face as she named the object or action that held the child’s interest. The coach also added sounds or gestures related to the actions on each page that the child found funny. As a result, the child looked briefly from the pages to the coach’s face. The child still wanted to turn the pages of the book ahead of the coach but he paused before doing so to check out the modeled action.

Through observation, the coach and parents can demonstrate knowledge and understanding of a skill and share particular challenges or difficulties blocking further progress. In the examples above, the coach observed the different learning opportunities the father created to elicit communication from his child, as well as the setbacks the mother experienced in reading a book with her child. Observation allows the coach and parent to reevaluate their progress toward reaching the goal(s) set forth at the start of the session and to revisit that plan or agenda with additional supports or resources when necessary. In the father’s case, the coach’s observation generated several activity ideas to help the father expand his teaching skills with more playful learning opportunities he can build inside the activity to promote the child’s use of communication. The selection of activities, learning opportunities, and communicative behaviors both short and long term become a part of the session’s plan for how to meet this goal. A similar process happens from the coach’s observation of the mother’s book routine with her child. The coach demonstrates additional techniques to refine the mother’s goal of sharing books with her son. The coach supports the child’s body and positions herself in front of the child to make it easier for the child to see her. Next the coach names the object or action of each picture the child looks at and adds playful sounds or gestures to entice the child to look at her. These modeled techniques and intended outcomes become a part of the session plan in development with the mother.

Coaching

With each conversation (whether coach or parent-led), the information gathered feeds into the coaching plan. It tells the coach and parents what is working to meet the goal versus what needs to be changed, problem-solved, or anticipated to reach the desired outcome. It helps the coach and parents plan what new strategies can support the goal and how they will be used to ultimately increase the child’s participation in family, community, or early childhood activities. In the P-ESDM , the style of coaching involves a method of communication to guide this conversation (at any point in the session) and to continue building the parents’ capacity to self-assess, self-correct, and expand skills to other situations.

Effective communication starts with parents feeling that they have been heard. When the parents believe that the coach is listening and understanding the message that they are trying to express, the parents are encouraged to share more information. Good listening means the coach is attentive with his or her whole body and with sincere interest in what the parents say. This includes direct eye contact, positive facial expressions, an open body posture, and appropriate proximity to the parents. The coach focuses on the present moment and listens to the words, meaning, and feelings expressed by the parents so as to acknowledge what they are trying to communicate. The coach does not pass judgment or take sides on the issue or topic.

As the coach passes the lead to the parents in these dialogues, the coach needs to be comfortable with the silences that may occur as the parents reflect and organize their thoughts. Quiet waiting is respectful of the parents’ thought processes, and it emphasizes how important the parents’ input is to the work going on.

When it is the coach’s turn in the dialogue, the coach’s goal is to build on the parents’ themes. One important technique for encouraging parents’ learning and self-discovery is asking open-ended questions to acquire additional information (e.g., “Tell me what you have tried so far?” “What are your child’s likes and interests at this moment?”) or to clarify (e.g., “What do you mean by noncompliant when you use that word to describe your son?” “Tell me more about everyone being concerned at your child’s school?”). A second important technique involves restating the content and feelings he or she has heard from the parents to confirm the information or clarify any miscommunication (e.g., “What I heard as your immediate priority for your child is to establish some boundaries or limits as to how often he plays with the i-Pad or watches television. Is that correct?” “So it becomes very stressful and worrisome to take your child outside of the house when you’re not sure how he will behave.”).

Another skill required of the coach is knowing how to provide just the right amount of feedback to the parents. Too much information can overwhelm a parent if not able or ready to process and understand what is being shared, whereas not enough information can leave the parent feeling unsatisfied or frustrated. In our P-ESDM approach, reciprocal evaluative feedback between coach and parents occurs after each parent-child activity, while the event is still fresh in the minds of the coach and the parents. It is descriptive: What the child’s specific response was to the parent’s specific behavior. This emphasizes the key relationship between parents’ acts and child learning. The information shared in this way is clear, concise, and specific to this parent and this child. The coach works hard to avoid using evaluative (e.g., “Good job,” “that was nice,” “I like…”) and directive or absolute words (e.g., “should,” “must,” “all the time,” “always”) with the parents. Reviewing and evaluating the session at the end in a dialogue between coach and parents help the parents solidify the learning content of the day, and it helps the coach understand the effectiveness of her use of the coaching tools.

Reflection

In reflection, the coach and parents engage in a back-and-forth discussion to help the parents analyze their practices and behavior in relation to the goal. The intent of the reflective discussion is for the parents to discover what they may already know or be doing, to identify what they may need to know or do, and to make any necessary or desired changes. The process unfolds through the coach’s use of questions, acknowledgments, and observations to explore what the parents have tried and think about those past efforts compared to the current situation or need. The coach actively listens and supports the parents in comparing their actions and observations to the characteristics of the effective intervention practices, research findings, or core values and beliefs. Throughout this process, the parents discover existing and new strategies and potential ideas to build on current strengths and address identified questions, priorities, and interests.

A main component to reflection is the question-asking process. The coach must ask good questions, at appropriate times, and in helpful ways (Kinlaw, 1999). Questions should encourage active thinking and elaboration from the parents rather than brief, “yes,” “no” responses. They should be open-ended, not closed. According to Hanft et al. (2004), questions may be objective, comparative, or interpretive. Objective questions start with “what,” “where,” “who,” or “how” to provide a framework to the parents for self-evaluation. Comparative questions help the parents compare current knowledge, experience, or practice to past actions, as well as to the desired outcome(s). Interpretive questions help the coach understand the parents’ impression of a specific situation so as to make a decision about what to do next in the session. Overall, reflection and the types of questions used by the coach assist in exploring how the parents think and feel about a given situation.

Example

The following coaching example illustrates the coach’s use of reflective questions and active listening as part of a coaching conversation with the mother of a 2-year-old son with ASD. The mother initiated the session’s topic with the goal of how to minimize her son’s repetitive hand and arm motions when excited by an activity. The coach began by inviting the mother to explain more about the current situation.

Coach: Tell me more about your son’s behavior. When is it likely to occur? How you respond when your son does this? What have you found to work or not work?

Mother: He’s most likely to do it when he really enjoys something, like playing with trains and cars. He will move the vehicle back and forth and then stop to shake his arms and hands. I tell him no or to stop and try to hold his hands to block him from doing the motion but it only makes him upset. I really haven’t found any strategy to work except for not playing with trains and cars. But then he will find something else he likes and the motion can happen again. Plus, I feel bad not letting him play with something he enjoys so much, especially if we can use his interests to help him learn.

Coach: What ideas do you have about how he could still have fun but without the repetitive movements, or less of it?

Mother: It’s important to me that he has fun but somehow to control his motions so he can attend and stay engaged with me. I notice that when he’s focused on something, like putting together the tracks or running the train over the tracks, he’s less likely to move his hands and arms.

Coach: So that may be something to explore. What other ways could you involve his hands and arms in the activity?

Mother: What if I gave him the bag to hold and we took turns taking out the tracks and putting them together? I could add blocks to the game for him to build a tunnel a bridge over the tracks as we run the trains under and over them. We could then knock them over with the trains and rebuild them to keep the game going. We could also add animal or people to ride on top of the trains so that he has to use his both hands to move them together.

Coach: Sounds like you have a lot of ideas to keep the game fun and his hands busy with purposeful actions.

Mother: Yes, I do. I’m excited to try this.

Coach: How about we set up these materials now for the two of you to get started in today’s session?

Mother: Great!

In this example, the coach used reflection to help the mother develop a plan for reducing her son’s repetitive movements during play. The coach began by asking the mother to reflect on how she currently handled her son’s repetitive movements and the success of the practice and actions compared to today. Then the coach asked open-ended questions to encourage the mother’s problem-solving. The information shared was useful as the coach helped the mother explore options for increasing functional play actions that would naturally interfere with the repetitive motions and yet skill maintain the child’s motivation and interest to participate. The coach sought to have the mother identify possible strategies to ensure her outcome for her son could be achieved in a meaningful way to his needs and likes. The reflection helped the mother identify ideas about what to do.

Once the coach has supported the parent in exploring his or her knowledge, skills, and experience related to the topic of the coaching conversation, the coach may facilitate additional reflection and discussion by providing feedback on the observation or practice. Feedback can be used to provide new insights to the parent regarding use of the targeted skill or practice. Feedback should follow the parent’s reflection so that the coach first understands the parent’s thoughts, ideas, and needs before providing recommendations. It should be clear and shared concretely with only the necessary information so that the parent knows exactly what the coach means. Feedback should also be shared in a timely manner as soon after the observation as possible or using as few words as possible if said during the observation to avoid disruption to the parent and child. Lastly, feedback should not criticize, blame, or be negative. It should promote confidence, trust, respect, and open communication. In the previous example, the story ended with the mother getting ready to play trains with her son in order to practice a new strategy. She had thought of actions she could encourage her son, Aiden, to do in lieu of moving his arms and hands back-and-forth. The coach observed the mother and child in practice with this approach and provides feedback once the activity ended.

Coach: I noticed that when you saw Aiden starting to move his hands in an excited manner, you gave him an item to hold or a play idea to do. You didn’t touch his hands or arm or tell him to stop. Rather, you provided ways in which he could engage with you, doing actions he liked and as a result, there were more opportunities to increase his play skills and understanding and use of language. Is there anything else you wanted to do or can think of now to continue working on this goal?

Mother: Sometimes I felt like I rushed him to help him physically do the play action or to tell him what to do because I wanted to stop the first sign of the movement. I could have waited at least a moment or two to see whether he would carry out the action by himself or what other ideas he might add to the activity.

Coach: That sounds like a good idea to build his independence both with physical movement of using his fingers, hands, and body to complete play actions and in his ability to be creative with the play and express his ideas to you. How will you try this?

Mother: I’m not sure. Do you have ideas?

Coach: The goal is to give him enough support without taking over for him. Last week we spent some time talking about and practicing least-to-most prompting.

Mother: Oh, that’s right. I remember that. Now let me think. Least to most means I would gradually provide more assistance if and when he can’t stop his hands from shaking. So when I see him starting to shake his hands, I could offer him an object and ask him a question like, “Does this train go next?” or a choice, “Should we build a tunnel or bridge?” to refocus his attention and get him to do something more appropriate with his hands.

Coach: Yes, those ways of using least-to most prompting assures that you can redirect him back to the activity as well as encourage his spontaneity of ideas, language, and play skills. What if he doesn’t take the object?

Mother: I don’t know what I should do next.

Coach: We want to add as much support as he needs to help him control his hands without just blocking his hands. Maybe you could bring the pieces closer to his hands or put them right in his hand so that it’s easier for him to pick them up and then carry out the action. You could also cover up the train, since we know the sight of it goes with his hand shaking. Then when he stops you could uncover it and try again. What do you think?

Mother: I could do those. They sound easy, and I think they will work fine.

Coach: Shall we stay with this and try these ideas in another activity?

Mother: I would like that.

Coach: What else is something he likes to shake his hands with that are not trains or cars so that you have more practice with other types of play?

Mother: I can’t think of anything right now.

Coach: I remember you sharing he also shakes his hands when he plays with water.

Mother: Yeah, he does.

Coach: I have some toys we could play with where he can scoop, pour, and spray water if you don’t mind him or yourself getting a little wet. You could engage his hands to do these actions and prevent his hand shaking the same way, as well as help him communicate the different actions and toys he wants or doesn’t want. What do you think?

Mother: I don’t mind water play, but let’s do it in the kitchen sink.

The coach provided feedback based on her observations of the mother’s practices. She encouraged the mother’s reflection on what occurred during the play with trains and shared additional strategies and later play ideas to extend the mother’s practice. Her feedback gave the mother a reason to reflect on how to increase her son’s independence and further direction to continue working toward this important priority. The session will continue to alternate between practice, observation, and reflection with the final coaching component of evaluation added to review the effectiveness of the coaching process, not to evaluate the parent.

Evaluation

Evaluation occurs after each coaching activity and at the end of the session to accomplish two goals. One is to assist the parents to make changes and progress toward the objectives and desired outcomes as they practice the intervention techniques. We have talked about the coach’s use of active listening and conversational strategies in the coaching section to elicit parents’ evaluation of their child’s and their own behavior and how to move forward in meeting personal goals. The second reason for evaluation is to check in with the parents about the usefulness and relevance of the coaching relationship and sessions conducted thus far. The coach may ask the parents how the sessions compare to meeting their goals, what other resources can be provided to aid their learning, and what changes they would recommend the coach make to improve the coaching relationship. The coach should also self-evaluate his or her coaching skills to make sure the approach, techniques, and communication are the best fit to serve the parents and child. This question may be posed to the parents, for their thoughts (e.g., “How do you like to learn something new?” “What other ways could I explain this technique to make it more relatable to your child?”), or stated as an observation of changes the coach would like to make in his or her own behavior (e.g., “The next time your child and I draw together, I will include other materials than markers, such as stickers and paints, and see whether this increases her participation and time in the activity.”).

Evaluation also helps to summarize the actions practiced in the session and to confirm the parents’ understanding before going home to practice the techniques further. In P-ESDM coaching sessions, a plan is finalized of how the parents will continue their practice of the information discussed. Details are specified by the parents, such as the behaviors, conditions, circumstances, and/or people involved in the practice and whether additional resources or needs will have to be considered in order to achieve desired outcomes. The plan is finalized of the steps, actions, people, and outcomes the parents will work toward in between sessions, and the plan is readdressed at the next point of contact to check in on progress and to continue developing as current goals are met and new needs are identified.

The coaching process ends when the parents have determined that the outcomes on the initial coaching plan and any additional goals that came out of the coaching experience have been achieved. The parents have developed the competence and confidence to move forward in present and future situations without the immediate need of the coach. Before the coaching relationship ends though, the coach and parents develop a final joint plan that outlines how the parents will continue to evolve their knowledge and skills. The plan should also consider the point at which the parents may resume the coaching relationship with the current coach or another individual in a coaching role, depending on the circumstance, type of support, and expertise needed by the parent.

Working with Parents’ Motivation for Change

Embedding child learning opportunities into everyday experiences in a purposeful fashion requires one to change typical patterns of one’s own behavior. Entering a process of learning from another involves a process of personal behavior change. This is not how we have typically viewed parent-implemented interventions. In fact, the field has not been very specific about what processes are actually involved, other than relationship-based processes. We have found it extraordinarily helpful to cast ESDM and other parent-implemented interventions as interventions in which parent behavior is being changed in explicit ways as a vehicle for changing child behavior in explicit ways. The value of this viewpoint is that it provides a number of empirically based tools and procedures, as well as a very important set of concepts, to incorporate into the early intervention work, namely, adult learning, cognitive behavioral techniques, methods for increasing and decreasing behaviors in the adult’s repertoire, and a very helpful body of evidence that comes from other types of interventions in the psychological literature – particularly substance abuse, weight loss, depression, anxiety, organization and time management, and personal growth literatures – that target changing the behavior of adults.

Personal growth manuals (e.g., Duhigg, 2012; Grant & Greene, 2001; Prochaska, Norcross, & DiClemente, 1994) provide helpful visuals, data collection systems, and adult self-management strategies for acquiring new, adaptive habits and curtailing unhelpful habits. We have these manuals on our bookshelves, use them ourselves, and gather ideas and tools that may help one or another family member as they add some repertoires to their own skills in order to add learning opportunities to their child experience. We find them invaluable in our work with parents and also in our work with supervisors, trainees, and colleagues.

A second literature that has been invaluable in our work in the past few years comes from the work on supporting adult motivation for change that has come from colleagues in the field of substance abuse treatment, and this is the work on motivational interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). While both of us are still very much learners in this field, we have found two sets of tools from this field extremely helpful in our work with families of young children with autism in several ways. First, we have found that the careful work done in this field on indirect verbal and nonverbal expressions of motivation in clients has helped us to listen and to “hear” parents’ motivational messages more clearly and to describe and restate motivational messages we perceive in dialogues with parents, bringing more attention to parent motivation in interactions with families.

Second, the MI dialogues and the stages of change concepts that adults undergo to change their behavior (i.e., pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and repair; Prochaska et al., 1994) have given us very helpful tools for supporting families to increase motivation for change and slowly become more active in the change process. This has been particularly helpful when working with families in which various adults are at different points in the motivation and change process. In the past, it has frequently been our experience that, when working with a couple for whom one member is quite motivated to provide new ways of working with their child at home, and the other parent is still working on the question of whether there is a problem with the child’s development or not, the interventionists tend to align with the parent who is motivated to move ahead, and the parent who is not yet at that point tends to be left out of the process, a situation that causes additional stress on the couple relationship and hurts rather than helps the family process. Using MI techniques, there is a respectful, active dialogue that can support each partner, a dialogue based on individual differences and individual insights combined with a shared love for the child and commitment to the family. By addressing each partner in terms of understanding and respecting their points of view, acknowledging the authority of both vis-a-vis their child, asking each for goals, and sharing information with both the intervention help them recognize their common ground and shared commitment and goals for their child’s best outcome. Parents are less likely to withdraw from the intervention process when their points of view and interactive skills with their child are acknowledged and respected and their contributions valued. Child change over time also lessens the differences between the two, particularly when child change is consistently attributed to both parents’ efforts and interactions.

A third very helpful contribution of MI work to our ESDM interventionists’ skills has been the idea of the inevitability of relapse, the idea that behavior change follows predictable cycles and that relapse, far from signaling failure, instead is an expected part of the process and does not represent an ending but rather the period before a renewal of energy and motivation for change. The dialogues for recognizing and addressing relapse without casting it as failure are extremely helpful for both the interventionist and the parents. Raising a child with autism takes decades or a lifetime. It is neither a marathon nor a sprint but rather a journey to an unknown continent, and the cycles involved in living a life – identifying challenges, setting goals, working to achieve them, making good progress, running out of steam, or getting ambushed by a different set of problems, taking a rest, picking up, and starting again – require a set of tools and a body of knowledge, and early interventionists are the first helpers in a family’s life to help them acquire the tools and learn to manage themselves through the cycles.

Supporting Fathers’ Engagement in the Intervention Process

A key component of practice of early intervention involves understanding how to work effectively with the adults, particularly the parents, who are involved in the lives of children in need of the services (Rush & Shelden, 2011). Fathers of children with autism are underrepresented in terms of understanding how to support their involvement in the early intervention process (Rivard, Terroux, Parent-Boursier, & Mercier, 2014). Fathers have unique interaction styles that can contribute to the development of their child and have cascading effects to the well-being of their family. If and when fathers are not involved in early intervention, coaches or interventionists may be missing important opportunities to maximize the social-communicative gains that come from parent-child interactions and exchanges. Overlooking fathers in intervention also may have unintended consequences for families, including increased levels of parental stress and decreased family cohesion as the result of one parent taking on the dual roles of caregiver and intervention provider (Rivard et al. 2014; Tehee, Honan, & Hevey, 2009). Therefore, increased father participation in early intervention may not only maximize the child’s development but also ease the overall workload and stress for mothers or other primary caregivers. Furthermore enhancing the role of fathers in early intervention marks an important direction in realizing optimal “family-centered ” services with all family members are involved in the process for children with autism (Shannon, Tamis-LeMonda, London, & Cabrera, 2002).

The ESDM approach to working with families centers on the rationale that intervention must be amenable to both parents and caregivers; otherwise it is not effective. This process starts at the beginning of the coaching relationship when the coach meets both parents and takes the time to understand each of their perspectives, needs, and priorities. To the best of everyone’s ability, sessions are scheduled with both parents present; otherwise effort is made from the coach to follow up via phone calls, video conferencing, etc. so that each parent is involved from the onset of intervention. It is equally important for both parents to have specific goals identified in the intervention plan. Just like mothers, fathers have their own ideas for what they want to gain from the coaching with their child and family. Ensuring fathers are involved in the goal-setting process gives them incentive to participate and follow the plan.

It is also important for the coach to follow both parents’ style of interaction with the child. Fathers and mothers have different approaches to communicating and playing with their child. Fathers may use a higher level of vocabulary and complex language models with more directive statements than mothers, and they tend to engage their child in more acts of symbolic play compared to mothers who engage in fewer play schemas (see Flippin & Crais, 2011 for a review). Coaching activities take into account how parents learn new information and the gender differences that may influence their own motivation to participate. Fathers have shared with us that embedding intervention within active or physical activities has made them feel more successful in helping their child learn. This may involve simple games done in the home or outdoors, such as playing chase, going to the playground, or swimming in the pool, or more elaborate activities such as participating in little league or other recreational teams. Finding out not only the child’s interests but the fathers’ as well and the activity settings that can support these interests can increase the likelihood that those opportunities are used for child learning and development. The coach can ask the father about his interests, the types of activities in which he participates with the child in a given day or week, and other less frequent activities that are important to do again. Some questions we have used with fathers (or with any parent) to elicit this information are:

-

How do you spend time as a family?

-

What do you enjoy doing with your child?

-

What activities are less enjoyable and why?

-

What activities do you wish you did more often with your child?

-

What interactions and skills would you like your child to develop?

This approach speaks to family-centered practice in which the coach uses and promotes what the parents are already doing or would like to do as a natural part of their family and community life. It provides a framework within which the coach can build from parents’ strengths and support their capacity to identify and use already available environments for engagement and learning. Even when families have limited activity settings and/or share minimal information, most participate in some type of eating, bathing, and dressing routines with their child. These activities may be a starting point to jointly identify child and adult interests for both parents and support participation and learning during family life activities. Remember that without interest, opportunity, and parent responsiveness, coaching cannot help promote child growth and development. Although the term parent still dominantly refers to mothers in autism early intervention research and clinical practice, our hope is that continued efforts to develop “father-friendly” methods will change this way of thinking.

Summary

In this chapter, we have descried many of the practices and techniques that have come from our work with families on embedding therapeutic practices into everyday activities and to increase children’s learning opportunities and learning rates. We have described a particular way of interacting with parents using a coaching framework and adult learning perspective. We have described parent-coach interactions that are grounded in parent goals for their child’s learning; consist of balanced, reflective, and evaluative interactions; focus on parent-child everyday activities; and address motivation of each partner.

We have evolved these practices from the existing literature in parent coaching (particularly writings by and dialogues with Hanft, Dathan Rush, and M’Lissa Shelden – thank you) and worked out in the therapeutic experiences we have had with families from many different cultures and walks of life in the Sacramento area. We have worked with single-parent families, families from many different ethnic backgrounds, families for whom English is a second (or third) language, and parents who themselves suffer from developmental disabilities. While many of the physical materials that we needed were individualized for each family, based on their preferred learning modalities, the materials they had at home, and their favorite activities to carry out with their children, we have used and built on the same interpersonal framework across all the families and have found it very flexible in its ability to create satisfying dialogues as well as measurable change in parent ways of interacting and child responses, as demonstrated in our various papers. Just as in our work with children, we have found that integrating concepts from developmental psychology relationship-based work and the science of learning, including adult learning, results in a very individualized interpersonal environment that fosters growth in child, parents, and coach as well.

References

Anderson, D. K., Rosalind, S. O., Lord, C., & Welch, K. (2009). Patterns of growth in adaptive social abilities among children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(7), 1019–1034.

Dawson, G., Jones, E. J. H., Merkle, K., Venema, K., Rachel Lowy, B. S., Faja, S., et al. (2012). Early behavioral intervention is associated with normalized brain activity in young children with autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(11), 1150–1159.

Duhigg, C. (2012). The power of habit: Why we do what we do in life and business. New York, NY: Random House.

Flippin, M., & Crais, E. R. (2011). The need for more effective father involvement in early autism intervention: A systematic review and recommendations. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(1), 24–50.

Grant, A., & Greene, J. (2001). Coach yourself: Make real change in your life. Cambridge MA: Basic Books.

Hanft, B. E., Rush, D. D., & Shelden, M. L. (2004). Coaching families and colleagues in early childhood. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Kinlaw, D. C. (1999). Coaching: For commitment: Interpersonal strategies for obtaining superior performance from individuals and teams. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

Lord, C., Luyster, R., Guthrie, W., & Pickles, A. (2012). Patterns of developmental trajectories in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(3), 477–489.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford publications, Inc.

National Research Council. (2001). Educating young children with autism. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Prochaska, J. O., Norcross, J. C., & DiClemente, C. C. (1994). Changing for good: The revolutionary program that explains the six stages of change and teaches you how to free yourself from bad habits. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers.

Rivard, M., Terroux, A., Parent-Boursier, C., & Mercier, C. (2014). Determinants of stress in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(7), 1609–1620.

Rogers, S. J., & Dawson, G. (2010). The early start Denver model for young children with autism: Promoting language, learning, and engagement. New York, NY: Guilford Publications, Inc.

Rogers, S. J., Dawson, G., & Vismara, L. A. (2012). An early start for your child with autism: Using everyday activities to help kids connect, communicate, and learn. Proven methods based on the breakthrough Early Start Denver Model. New York, NY: Guilford Publications, Inc.

Rush, D. D., & Shelden, M. L. (2011). The early childhood coaching handbook. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Shannon, J. D., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., London, K., & Cabrera, N. (2002). Beyond rough and tumble: Low-income fathers’ interactions and children’s cognitive development at 24 months. Parenting: Science and Practice, 2(2), 77–104.

Tehee, E., Honan, R., & Hevey, D. (2009). Factors contributing to stress in parents of individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22(1), 34–42.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Vismara, L.A., Rogers, S.J. (2018). Coaching Parents of Young Children with Autism. In: Siller, M., Morgan, L. (eds) Handbook of Parent-Implemented Interventions for Very Young Children with Autism. Autism and Child Psychopathology Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90994-3_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90994-3_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-90992-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-90994-3

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)