Abstract

As Riël Vermunt, Ali Kazemi, and Kjell Törnblom point out in this chapter, resource allocations may be judged on the basis of the resulting final outcome and/or the procedures applied to arrive at the outcome. The focus of this chapter is on how attention to the outcome or procedure is affected by the nature of the allocated resource (universalistic versus particularistic) and the direction of allocation (when P is a provider versus a recipient). Results from a cross-national survey study involving respondents from Austria, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the USA showed that procedure was perceived as more focal in the allocation of universalistic as compared to particularistic resources. No differences were observed with regard to the salience of outcome. Interestingly, this held only true for resource providers; for resource recipients, this pattern was reversed. These and other findings suggest that the meaning of resource classes (in this study money and love) differ for providers and recipients in their judgments of allocation events. The authors conclude by discussing the implications of these findings for SRT and for future research.

We would like to thank Robert Folger, Gerold Mikula, and Paul van Lange for collecting the data in USA, Austria, Italy, and the Netherlands, respectively.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction: Outcome or Procedure?

A minimally meaningful description of a resource allocation event will include information about the object of allocation (i.e., the type, amount, and valence of the resource); whether the result of the allocation is positive or negative (i.e., outcome valenceFootnote 1); whether the event is considered from the perspective of the recipient, the provider, or a third party; and within what kind of social relationship, setting, institutional, and sociocultural context the allocation takes place. These factors have been shown to affect fairness evaluations of the outcome and the choice of a distribution principle (Törnblom 1992). It seems reasonable to expect that the relative salience of (or focus on) the outcome and the procedures enacted to accomplish the outcome would also be affected by the mentioned variables.

Increasingly, contemporary justice theorists assume that a meaningful overall (total) fairness assessment of a situation or an event requires assessments of both the distribution Footnote 2 (the outcome or end result) and the procedure (the means) by which the distribution is accomplished. Most contemporary justice theorizing assumes that the two cannot be studied in isolation from each other (e.g., Brockner and Wiesenfeld 1996; see also Törnblom and Vermunt 1999, for more details and a model for integrating these two allocation components). Lind and Tyler (1988), for example, proposed that procedural fairness assessments are at least as important as distributive fairness assessments for overall justice evaluations in legal and organizational settings. Törnblom and Vermunt (1999) postulated that the perceived total fairness of a situation is a function of fairness assessments of both the distribution and the procedure, and when both distribution and procedure are salient, their fairness assessments are likely to be interdependent. Much research efforts have thus been devoted to mapping perceived justice of social encounters as a function of both outcome and procedure independently as well as interactively. However, research dealing with the salience of each in making judgments about allocation events is scarce, and the research reported in this chapter examines this latter focus.

Focusing the relative salienceFootnote 3 of the outcome and the procedure in people’s evaluations of an allocation event generates some interesting questions: Under what conditions do outcome and procedure play equally important roles in people’s experiences? Under what conditions is one experienced as more figural and weighty than the other? Under what means and to what extent might they interact with one another? Researchers have argued that (1) procedural aspects may be more important than the outcome (because they seem to affect overall satisfaction to a greater degree), and that (2) the fairness evaluation of a particular outcome may be affected by the fairness of the procedures that produced it – the fair process effect (e.g., Lind et al. 1983; Lind and Tyler 1988). Thus, fair procedures may lessen the disappointment associated with unfair outcomes. Gilliland (1993) predicted that (1) the perceived justice of the procedure will have the greatest impact on overall justice evaluations when distributive justice rules have been violated, and that (2) the perceived justice of the outcome (distribution) will have the greatest impact on overall justice evaluations when procedural justice rules have been violated. Leventhal (1980) proposed that distributive fairness is assumed to be generally more salient than procedural justice and is, thus, more important in determining overall fairness. On the other hand, procedural fairness has greater influence on overall fairness judgments (a) when organizations are being created, and (b) when people are dissatisfied with the distribution of outcomes (in which case procedures are examined more closely to find explanations of the unsatisfactory outcome and justifications for change). Other consistent findings in the organizational justice literature are that procedural justice perceptions tend to account for more variance in attitudes about institutions and authorities as well as being more strongly related to global attitudes (e.g., organizational commitment) than do distributive justice perceptions (which appear to be more related to specific attitudes such as job and pay satisfaction) (e.g., Ambrose and Arnaud 2005). Törnblom and Kazemi (2010) found that the outcome was more important than the procedure for fairness judgments of an offense (theft as well as physical abuse) regardless of its severity.

The major focus of the study reported here concerns how perceived importance (salience) of the outcome and procedure is moderated by the nature of allocated resource [love (liking and caring) vs. money (monetary gift and financial help)] and by the direction of allocation (giving vs. receiving).

Resource Type

Several studies suggest that the allocated resource affects people’s justice conceptions concerning the outcome distribution (e.g., Sabbagh et al. 1994; Törnblom and Foa 1983; Törnblom et al. 1985). Thus, the analysis and understanding of a particular outcome allocation is incomplete and less meaningful without information about the resource changing hands. The most commonly used classification of resource types was provided by Foa (1971) in the context of his resource theory of social exchange (see also Foa and Foa 1974). Within this framework, love, status, and service are particularistic resources; their values derive mainly from the identity of the provider and/or from the relationship between the provider and the recipient – which is not the case for universalistic resources (information, goods, and money). Particularism and universalism are extremes on a single continuum rather than discrete categories. The degree to which a resource is predominantly valued as particularistic or universalistic is affected by the social context in which it is transacted. Resource classes are further differentiated along a dimension ranging from concrete to symbolic. This dimension pertains to the type of behavior that is characteristic for the exchange of a particular resource: providing a good and doing someone a favor are concrete behaviors, conveying status and information are symbolic/abstract behaviors, while love and money are located between these two extremes as they may be provided both symbolically (e.g., verbal expressions of affection and as stock or other tokens, respectively) and concretely (e.g., sexual acts and hard currency, respectively).

As resource classes in RT differ on two dimensions and it is the impact of particularism that is the focus of the current study, the resource classes examined were chosen to be similar with regard to their position on the concreteness dimension. Thus, the two resource classes differ the most on the particularism dimension while occupying the same position on the concreteness dimension (i.e., love and money).

As stated in RT, it is the symbolic meaning of the resource (rather than the resource, per se) that is typically focal. Importantly, and relevant to the purpose of this chapter, the way in which a resource is provided may affect its meaning. You cannot present a token of respect (e.g., a gold watch meant to symbolize an organization’s appreciation of your loyal services during 25 years) unless the token is presented via respectful behavior (i.e., an appropriate procedure). The procedure by which a universalistic resource is provided can “make or break” the intended result of the interaction. If the provider who wishes to convey love and affection fails to act with sensitivity and warmth (i.e., via an appropriate procedure) when handing over money, for instance, only the money, per se, might be the focal (salient) outcome.

The significance of a particularistic resource (such as affection, warmth, regard, admiration) is likely to be relatively unambiguous with regard to the purpose of its provision. For instance, when you receive a hug, you most likely understand that he/she wants to convey affection for you. However, giving a universalistic resource (e.g., a book, a piece of information, a chocolate bar) is not equally unambiguous. The book gift might be your way of saying that you like the recipient, but you may also present the gift for very different reasons. If you do not wish to convey liking, you must pay attention to just how you present the book or give the hug. Thus,

-

Hypothesis 1: The procedure is more focal when universalistic than when particularistic resources are allocated.

Procedure (universalistic resource allocation) > Procedure (particularistic resource allocation)

What about the outcome then: Is the outcome focal in the same way as the procedure? We find no basis for predicting why outcome would be more focal for either kind of resource allocation. As previously stated, the procedure is more focal for universalistic resource allocations. Intuitively, one would perhaps assume the opposite – verbal praise provided with a disapproving facial expression makes the message obsolete. Thus, the meaning of particularistic resources like love and status are straightforward which is not the case for most universalistic resources. One can interpret the meaning of giving a book as a sign of affection, a source of information, or repayment for a previous service. Therefore, we argue that the procedure by which a universalistic resource is provided serves to reduce the possible ambiguity associated with the provision or receipt of the resource. Following this line of reasoning, it seems reasonable to conclude that the procedure is more salient for the allocation of universalistic than for particularistic resources, and that this difference is larger than the corresponding difference when outcome is considered. Thus,

-

Hypothesis 2: The difference between the salience of procedure in the evaluation of a universalistic as compared to a particularistic resource allocation is greater than that for the outcome distribution.

Procedure (universalistic – particularistic resource allocation) > Outcome (universalistic – particularistic resource allocation)

Allocation Direction

In this chapter, we focus on the direction of allocation and examine two situations: (1) P allocates resources to others (“giving”) and (2) P is the recipient of resources provided by others (“receiving”). Research on the two perspectives of givers (i.e., resource providers) and recipients is highly scattered in the literature. In the ultimatum game, two players interact to decide how to divide a sum of money. The first player (the allocator) proposes how to divide the money between herself and the other player (the recipient), and the recipient can either accept or reject this proposal. If the recipient rejects the offer neither player receives anything. If the recipient accepts, the money is split according to the offer. In a dictator game, the allocator determines how to divide a particular endowment (most often money), and the recipient simply receives the remainder of the endowment left by the allocator. Results from ultimatum and dictator game research indicate in general that allocators are driven by both a fairness motive and self-interest, presumably because they are corecipients of the resource (e.g., van Dijk and Vermunt 2000; Handgraaf et al. 2004).

Furthermore, Flynn and Brockner (2003) found in a study on favor exchange among peer employees that givers’ and receivers’ commitment to their relationship (i.e., their willingness to invest energy in the relationship and being loyal to it) was motivated by different factors. Specifically, favor givers’ commitment to the relationship was more strongly associated with the amount of aid and services they provided, while favor recipients’ commitment was more strongly associated with how the favor was enacted (i.e., helpful behavior that was provided in a demeaning manner was less or not at all appreciated by the receivers). Thus, previous empirical findings (see also Lissak and Sheppard 1983) suggest that allocators and recipients may have somewhat different foci in resource allocation situations. Thus, we predict that:

-

Hypothesis 3: Resource providers are more focused on the outcome of their allocation than on the procedure by which the outcome is accomplished.

Resource providers (outcome focus > procedure focus)

-

Hypothesis 4: Resource recipients, in contrast, are less focused on the outcome than on the procedure by which the outcome is accomplished.

Resource recipients (outcome focus < procedure focus)

However, in real life, it is not always true that resource recipients are more concerned with the procedure and resource providers (as well as decision makers) with the outcome. In support of this reasoning, Heuer, Penrod, and Kattan (2007) reported that decision makers are not only influenced by instrumental criteria (i.e., outcome concerns) but also by relational concerns. Specifically, decision makers did not differ from decision recipients in that they placed an equal emphasis on respectful treatment when securing the group’s welfare was taken into account (see also Sivasubramaniam and Heuer 2008).

Another purpose of the present study was to examine how allocation direction interacts with resource type in affecting the perceived importance (salience) of the outcome and the procedure. Interestingly, we expected that taking resource type into account would reverse the patterns predicted by Hypotheses 3 and 4. In the following, we continue our theoretical line of reasoning by focusing on the salience perceptions of outcome and procedure separately rather than together like they usually appear in real-life situations. Thus, the aim is not to compare salience perceptions of outcome with salience perceptions of procedure but to discuss the relative salience of each for resource providers versus resource recipients under the conditions of universalistic versus particularistic resource allocations.

When it comes to the salience of outcome, we previously posited that resource providers (i.e., givers) focus more on the outcome of the allocation, and this is not assumed to be moderated by the nature of allocated resource. Outcome salience is unaffected by whether the allocation involves a particularistic or a universalistic resource. However, the situation might look differently from the recipient’s perspective. Two arguments, previously stated, support this contention. As the amount of a universalistic resource is more easily assessed than the amount of a particularistic resource, it is argued that an allocated outcome (of a certain amount) is more focal in universalistic resource allocations. Thus,

-

Hypothesis 5: Resource recipients are more focused on the outcome in allocations of universalistic as compared to particularistic resources.

Resource recipients (universalistic outcome focus > particularistic outcome focus)

When it comes to the salience of procedure for resource providers and resource recipients, a somewhat reverse pattern is expected. Specifically, as previously argued, ensuring the satisfaction of the recipients is focal for resource providers and for the group of recipients, and equality of treatment (cf. the procedural rule of consistency, Leventhal 1980) is highly salient. This leads us to assume that resource providers are more focused on the procedure in the case of universalistic as compared to particularistic resource allocations. Thus,

-

Hypothesis 6: Resource providers are more focused on the procedure in allocation of universalistic as compared to particularistic resources.

-

Resource providers (universalistic procedure focus > particularistic procedure focus)

For resource recipients, the way providers behave toward them (i.e., the procedure) when allocating a resource is also important and focal. Lind and Tyler (1988) argued that the procedure (or the way of acting toward others) is important because it conveys the recipients’ status in the group. Interestingly, and in contrast to the perspective of providers, we argue that the procedure (which is aimed at ensuring the group’s welfare and satisfaction) is important to resource recipients regardless of the nature of the provided resource. Thus, there seems to be no compelling reason for expecting that there will be a stronger focus on the procedure in the allocation of particularistic as compared to universalistic resources.

Method

Data were collected as part of a large cross-national survey among students from five countries: Austria (N = 400), Italy (N = 89), the Netherlands (N = 378), Sweden (N = 213), and the USA (N = 391). The total sample consisted of 32.6% male and 67.4% female respondents. Respondents’ age varied from 20 to 70 years with a mode of 21 years. In all countries, respondents were recruited mainly from psychology and sociology classes.

A 2 (allocation direction: giving vs. receiving) × 2 (resource type: particularistic vs. universalistic) × 2 (allocation focus: outcome vs. procedure) mixed design was employed.Footnote 4 The last two were repeated measures factors, and the salience of outcome and procedure for allocation decision served as the dependent variable.

We chose a table-wise presentation of the questionnaire as it made it easier to the respondents to compare their answers within one question (table) and because it was less space consuming. Each table consisted of four rows and five columns resulting in 20 cells. For each table, the upper-left cell, where row 1 and column 1 cross, contained the question to be answered; the cells of row 1 and the four other columns contained the labels of the four types of relationship used, respectively: your partner in a love relationship (A), a good friend (B), your child (C), your coworker (D). The question to be answered was:

“If each person (A–D) listed to the right would show you that he/she likes you (the receiving mode) (in the money scenario it reads receive financial help/monetary gift) what would you pay most attention to?”

-

1.

The amount, i.e., how much he/she likes you (row 2 of column 1).

-

2.

The way in which he/she shows it to you (row 3 of column1).

-

3.

Both the amount and the way, they are equally important (row 4 of column 1).

In another similar version of the questionnaire, receiving was replaced by giving. “If you would show (give) each person (A–D) listed to the right that you like him/her (in the money scenario it reads give financial help/monetary gift), what would you pay most attention too?”

The instructions to the respondents read as follows: “The following items contain three response alternatives. Even though you might think of additional alternatives, please restrict your choice to those given here. Make one (and only one) choice that comes closest to your opinion for each person (A–D). Thus, a full answer to each question requires you to make four choices – as the following example illustrates:”

If each person (A–D) listed to the right would give you some instructions you need, what would you pay most attention to? | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Your partner in a love relationship | A good friend | Your child | Your coworker | |

1. The amount of instructions you get | ✓ | |||

2. The way in which he/she conveys them to you | ✓ | |||

3. Both the amount and the way, they are equally important | ✓ | ✓ |

Results

Prior to data analyses, the raw scores were transformed in the following way: Respondents indicated how much attention they would pay to the outcome, the procedure, or to both equally in allocating two types of resources (particularistic and universalistic). For each resource type, we separately counted the number of times a respondent paid attention to the (1) outcome, (2) procedure, and (3) both outcome and procedure. The transformation resulted in the creation of three levels of the variable allocation focus – with each level concerning the salience of outcome, procedure, and equal salience of outcome and procedure, respectively. Thus, for each level of the variable allocation focus, importance scores varied from 0 (no attention paid) to 2 (full attention).

The Salience of Outcome and Procedure in Allocation Decisions

The effects of allocation focus on importance of outcome and procedure were significant, F(1, 1468) = 811.2, p < 0.01. The Helmert procedure revealed that differences should be larger than 0.08 to be significant (Stevens 2002). There was a stronger focus on the procedure (M = 0.74) than on the outcome (M = 0.34).

The Effects of Resource Type on the Salience of Outcome and Procedure in Allocation Evaluations

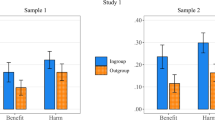

The two-way interaction of resource type by allocation focus was significant, F(1, 1468) = 6.57; p < 0.01. The Helmert procedure revealed that differences should be larger than 0.075 to be significant (Stevens 2002). In Table 25.1, the mean focus ratings on outcome and procedure for particularistic and universalistic resource allocations are depicted.

Table 25.1 shows that allocation of universalistic resources triggered a stronger focus on the procedure (M = 0.80) than the allocation of particularistic resources (M = 0.68). Hypothesis 1 was thus confirmed. Furthermore, as expected, the difference between the salience of procedure in the evaluation of a universalistic as compared to a particularistic resource allocation was greater (0.80 − 0.68 = 0.12) than the corresponding evaluation concerning the salience of outcome (0.37 − 0.31 = 0.06). Hypothesis 2 was thus also supported.

The Effects of Allocation Direction and Resource Type on the Perceived Salience of Outcome and Procedure

The two-way interaction of allocation direction by allocation focus was, as expected, significant, F(1, 1468) = 19.13, p < 0.01. The Helmert procedure revealed that differences in means should be larger than 0.10 to be statistically significant (Stevens 2002).

Resource providers were less focused on the outcome (M = 0.37) than on the procedure (M = 0.71), disconfirming Hypothesis 3. In contrast and as expected, resource recipients were more focused on the procedure (M = 0.78) than on the outcome (M = 0.32), which confirmed Hypothesis 4. As the pattern of means clearly shows, both resource providers and recipients were more focused on the procedure than on the outcome, the differences between procedure and outcome for both providers and recipients were therefore explored. Interestingly, this revealed that the difference between procedure and outcome for resource recipients was larger (i.e., 0.78 − 0.32 = 0.46) than the corresponding difference between procedure and outcome for resource providers (i.e., 0.71 − 0.37 = 0.34). A closer scrutiny of these findings also revealed that outcome was perceived as more focal for providers than for recipients, and that the procedure was more focal for recipients than for providers, corroborating our line of reasoning.

The three-way interaction of allocation direction, resource type by allocation focus was significant, F(1, 1468) = 26.80, p < 0.01. The Helmert procedure revealed that differences in means should be larger than 0.088 to be statistically significant (Stevens 2002). Means are depicted in Table 25.2.

With regard to outcome, allocation direction moderated the effects of resource type on the perceived salience of the outcome. That is, recipients had a stronger focus on the outcome in the allocation of universalistic (M = 0.42) as compared to particularistic resources (M = 0.30). Hypothesis 5 was thus confirmed. In contrast, data revealed that it did not matter for the providers whether particularistic or universalistic resources were allocated. That is, for providers, outcome was seen as equally important in allocation of universalistic (M = 0.33) and particularistic resources (M = 0.32)

With regard to procedure, allocation direction also moderated the effects of resource type on the perceived salience of the procedure. Specifically, providers focused more on the procedure in the allocation of universalistic (M = 0.87) as compared to particularistic resources (M = 0.69). Hypothesis 6 was thus confirmed. For recipients no such effect was found (M universalistic = 0.73 vs. M particularistic = 0.68).

Concluding Comments

In this chapter, the question raised and examined was whether it is the outcome or the way the certain outcome has been accomplished (as well as the relative extent of each) that is focal in a resource allocation event. The novelty of this research is in its consideration of the nature of the allocated resource from the perspectives of both resource providers and resource recipients.

Procedure was conceived as more focal when universalistic than when particularistic resources were allocated. The amount of a universalistic resource can be more easily determined than the amount of a particularistic resource. The amount of love one gives or receives is rather ambiguous and open to subjective interpretation. Subjective assessments of universalistic resources are far less frequent – a dollar is a dollar. Because the precise amount of a universalistic resource can usually be determined relatively quickly as compared to the amount of a particularistic resource, evaluations of the procedure, if called for, may be taken on early in the overall fairness evaluation process. As this is not the case for a particularistic resource, the assessment of which typically requires more time due to the ambiguity of its subjective nature. This might explain the finding that procedure was deemed as more focal for universalistic than for particularistic resource allocations.

Both resource type (universalistic or particularistic) and allocation direction (i.e., providing or receiving a resource) turned out to be crucial factors accounting for differences in the perceived relative salience of outcome and procedure. Our findings suggest that the impact of the distinction between money and love was not as straightforward as expected based on their position along the particularism dimension in the circular structure proposed by Foa. Specifically, the salience of the outcome was the same for universalistic and particularistic resources. In contrast, procedure was more salient when universalistic resources were allocated than when particularistic resources were allocated.

Two other interesting observations were that recipients of a universalistic resource focused more on the outcome than did recipients of a particularistic resource. In contrast, procedure was equally salient in allocations of universalistic and particularistic resources. A somewhat opposite pattern emerged for resource providers. Specifically, whereas resource providers attached equal importance to the outcome in allocation of both resource types, they tended to focus more on the procedure in the allocation of universalistic than when particularistic resources were allocated.

To conclude, an important point of departure for this chapter was that the perceived justice of a situation is frequently a function of both outcome and procedure, but the salience of each may vary when making justice judgments. The findings suggest that the nature of allocated resource triggers different foci on outcome and procedure and that the perspective from which the judgment was made played an important role.

Notes

- 1.

The valence of the resource and the outcome may not necessarily have the same sign. A student may be assigned extra homework (i.e., negative resource valence) which in turn might lead to better grades (i.e., positive outcome valence).

- 2.

The terms “distribution” and “outcome” will be used interchangeably to refer to the endstate of a resource allocation event.

- 3.

Outcomes and procedures may, of course, be evaluated in terms of various other types of criteria than salience, such as preference, acceptability, expediency, appropriateness, importance, impact, desirability, efficacy, satisfaction, and fairness. Various factors determine what values are assigned to each of these different criteria, and it may well be that some factors are appropriate for all criteria, while certain other factors are only meaningful for some of the criteria. In this study, we examine the impact of two factors – resource type and direction of allocation.

- 4.

The study reported herein included two additional variables, that is, social relationship and resource valence, the results from which will be reported elsewhere. For the purpose of this chapter and simplification of the original design we chose to focus on the roles of resource type and allocation direction for the perceived relative salience of outcome and procedure in resource allocation events.

References

Ambrose, M. L., & Arnaud, A. (2005). Are procedural justice and distributive justice conceptually distinct? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice (pp. 59-84). Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Brockner, J., & Wiesenfeld, B. (1996). An integrative framework for explaining reactions to decisions: Interactive effects of outcomes and procedures. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 189–208.

Flynn, F. J., & Brockner, J. (2003). It’s different to give than to receive: Predictors of givers’ and receivers’ reactions to favor exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 1034–1045.

Foa, U. G. (1971). Interpersonal and economic resources. Science, 71, 345–351.

Foa, U. G., & Foa, E. B. (1974). Societal structures of the mind. Springfield: Charles Thomas.

Gilliland, S. W. (1993). The perceived fairness of selection systems: An organizational perspective. Academy of Management Review, 18, 694–734.

Handgraaf, M., Van Dijk, E., Wilke, H., & Vermunt, R. (2004). Evaluability of outcomes in ultimatum bargaining. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 95, 97–106.

Heuer, L., Penrod, S., & Kattan, A. (2007). The role of societal benefits and fairness concerns among decision makers and decision recipients. Law and Human Behavior, 31, 573–610.

Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In K. J. Gergen, M. S. Greenberg, & R. H. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 27–55). New York: Plenum.

Lind, E. A., Lissak, R. I., & Conlon, D. E. (1983). Decision control and process control effects on procedural fairness judgments. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13, 338–350.

Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. New York: Plenum.

Lissak, R. I., & Sheppard, B. H. (1983). Beyond fairness: The criterion problem in research on dispute resolution. Journal of Applied Psychology, 13, 45–65.

Sabbagh, C., Dar, Y., & Resh, N. (1994). The structure of social justice judgments: A facet approach. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 244–261.

Sivasubramaniam, D., & Heuer, L. (2008). Decision makers and decision recipients: Understanding disparities in the meaning of fairness. Court Review, 44, 62–70.

Stevens, J. P. (2002). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. London: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Törnblom, K. (1992). The social psychology of distributive justice. In K. R. Scherer (Ed.), Justice: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 177–284). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Törnblom, K., & Foa, U. G. (1983). Choice of a distribution principle: Crosscultural evidence on the effects of resources. Acta Sociologica, 26, 161–173.

Törnblom, K., Jonsson, D. R., & Foa, U. G. (1985). Nationality, resource class, and preference among three allocation rules: Sweden versus USA. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 9, 51–77.

Törnblom, K., & Kazemi, A. (2010). Justice judgments of physical abuse and theft: The importance of outcome and procedure. Social Justice Research, 23, 308–328.

Törnblom, K., & Vermunt, R. (1999). An integrative perspective on social justice: Distributive and procedural fairness evaluations of positive and negative outcome allocations. Social Justice Research, 12, 37–61.

Van Dijk, E., & Vermunt, R. (2000). Sometimes it pays to be powerless: Strategy and fairness in social decision making. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 36, 1–25.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Vermunt, R., Kazemi, A., Törnblom, K. (2012). The Salience of Outcome and Procedure in Giving and Receiving Universalistic and Particularistic Resources. In: Törnblom, K., Kazemi, A. (eds) Handbook of Social Resource Theory. Critical Issues in Social Justice. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4175-5_25

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4175-5_25

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-4174-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-4175-5

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)