Abstract

The study, conducted in Malaysia, examined the role of recipient–allocator relationship in perceived choice of resource allocation norms (equity, equality, and need) on two types of resources (money and favour) and the degree to which they were considered fair. Subjects responded to vignettes that described a resource to be allocated by an allocator between a needy and a meritorious employee. Recipients relationship status in the vignettes indicated that one of the two was the brother of the allocator who was either meritorious or needy. In the control group, no relationship characteristic of the recipient was stated. Results indicated that equality was the most fair and preferred norm of justice. No significant difference was obtained among the perceived norm and fairness in all but one situation (distribution of loan). The results are discussed in relation to the subjects’ cognitive strategy and collectivistic values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is a growing interest, among organisational and social psychologists, in the study of “justice behaviour” where the main focus is to examine how individuals, who control resources, decide what rules of distribution are fair and how the recipients react to the distribution (Fischer & Smith, 2003; Krishnan, Varma, & Pandey, 2009). The rules may be equity, equality, or need. The equity rule requires that resource allocations be proportional to the merit or contribution of the individual recipient, the equality norm advocates an equal distribution irrespective of the size of the contribution, and the need rule requires that allocation should be in accordance with the intensity of the needs of a recipient. Few other rules such as recipient’s social skill (Giacobbe-Miller, Miller, & Victorov, 1998; Lin, Insko, & Rusbult, 1991) and tenure (Chen, 1995; Hundley & Kim, 1997; Mahler, Greenberg, & Hayashi, 1981) are also included in subsequent studies. Which of the rule is used by an individual depends upon several factors such as the type of resources, purpose of the resource distribution, relationship characteristics between the allocator and the recipient, and the sociocultural context in which the allocation process occurs.

There is a great paucity of research studies conducted in this area in the Malaysian context. Being a collectivistic and relationship-oriented society, it was of interest to examine the norms of resource allocation and perception of fairness in Malaysia. More specifically, the study examined how decisions regarding resource allocation are made in work situations and how factors such as the type of resources and the relationship between allocator and the recipient influence the allocation decisions. It also examined the perceived fairness of the allocation decisions. Review of the literature suggested scarcity of studies that have examined the role of resource type and the allocator–recipient relationship factors in allocation decisions. This was our research motivation.

The extant literature suggested that that there are three independent norms of justice, namely, equity, equality, and need which are generally used in allocation decision studies (see Greenberg & Cohen, 1982). The equity norm takes into consideration the “inputs” or contribution made by recipients. Equality norm ignores the differential contributions of recipients and leads to an equal distribution of resources to all involved. The need principle requires that resources be allocated in response to recipients’ legitimate needs and to prevent suffering.

Which of these norms is used and considered fair depends on the characteristics of the allocator and the recipients, the type of resource, the situation, and culture. For instance, research studies conducted in the USA indicated that the norm of equity is likely to predominate in situation of an economic nature, that is, where money or goods are involved and when production and efficiency are important (Leventhal, 1976). The norm of equality comes into play when group harmony and positive social relations are important (Deutsch, 1975). Lerner, Miller, and Holmes (1976) reported that equality is preferred when there is an expectation of future interaction because of the likelihood of some form of reciprocity or retaliation, or simply because it may enhance the case of subsequent social interaction. However, the need norm will predominate in situations where fostering personal welfare and development is of interest and when the relationship among the actors is close and friendly (Mikula & Schwinger, 1978).

Krishnan et al. (2009) conducted a study in India using both reward and punishment as resources. They examined the effect of allocator–recipient relationship and internal versus external location of merit on both reward and punishment distribution involving a meritorious and needy recipient. The findings indicated a dominant choice of equality for reward. In case of punishment, both need and merit were given equal importance.

In a survey study in Malaysian organisations Hassan and Ahmed (2001), employees are asked to rate their perception of allocation norms (merit, need, or merit and need together) commonly followed in their organisations on issues that included employment, promotion, placement, perks, foreign assignment, training, leave, loan, performance appraisal, reserved parking space, office space, and confidential information. Findings indicated merit of the employees as the most preferred norm in eight out of 12 cases. However, in case of grant of loan to any employee, merit together with need was rated the most likely consideration. In case of providing training, grant of leave, and providing office space, need was given the top endorsement.

Types of Resources

Little research within the distributive justice paradigm has been done on the nature of resources being distributed. Several scholars such as Homans (1961) and Thibaut and Kelley (1959) argued that the norms of allocation apply to both tangibles and intangibles and extend to subjects, events, or affective states.

Otto, Baumert, and Bobocel (2011) investigated the use of distributive justice rules using two types of resources, namely material benefits such as monetary rewards and symbolic benefits such as praise, in a cross-cultural study involving Canadian and German student sample. Using uncertainty avoidance/uncertainty tolerance as the cultural difference between the two groups, they reported that when allocating material benefits, Canadian found equity principle to be fairer than Germans. However, when it came to symbolic benefits, Canadian perceived equality as more just than Germans.

Allocator–Recipient Relationship

There is evidence that the nature of relationship between allocator and recipient may as well influence the allocation decision. For example, Benton (1971) found that American males allocated to both friends and strangers on the basis of equity but females used equity for strangers and equality for friends.

One of the critical features of a relationship is the opportunity afforded for future interaction and potential reciprocity, both conditions which enhance the probability of equal rather than equitable allocations. Thus, family members are highest in this regard and strangers the lowest with friends and acquaintances in between.

Lerner (1974) suggested that the form the allocation will take depends on the type of relationship we perceive we have with another, and whether we perceive the other as a person or as an occupant of a position. These range from the remote which he termed “non-unit” relationship to closer “unit” relationship, to the closest, “identity” relationship. Similarly, Greenberg and Cohen (1982) suggested that the relationship between individuals can be placed along two independent dimensions, i.e. interdependence and intimacy. Intimacy is defined as the closeness of the social bond between individuals and interdependence as the degree to which participants in a social exchange have control over each other’s resources. Thus, strangers would be low on both the factors, friends high in intimacy and low on interdependence and family high on both. Within this framework, self-interest should prevail when dealing with strangers, equality with friends, and sensitivity to mutual needs in family situations. In a most recent cross-cultural study involving Taiwanese and European American students, Wu, Cross, Wu, Cho, and Tey (2016) compared priority of family relationships (mother or spouse) in helping decisions, using hypothetical life-or-death and everyday situations. Result suggested that in both the situations, Taiwanese participants were more likely than European American to choose to help their mothers instead of their spouses. Furthermore, Taiwanese were more likely than European Americans to choose to help their mothers instead of their sibling or their own child. Mediation analysis indicated that obligation and closeness accounted for the association between culture and certainty of saving the mother or spouse in the life-or-death situation.

The Influence of Culture

There are enough studies to suggest that, while the norms of justice may be universal, the conditions under which they are implemented and the relative importance assigned to them is not consistent across cultures. For example, much higher preference for equality norm was found in Columbia, Japan, Hong Kong, and India than in the USA (Leung & Bond, 1982; Marin, 1981; Krishnan et al. 2009). Studies conducted in India, reported as a collectivistic culture, provide conflicting results. While some studies (e.g. Aruna, Jain, Choudhary, Ranjan, & Krishnan, 1994; Berman, Murphy-Berman, & Singh, 1985; Murphy-Berman, Berman, Singh, Pachauri, & Kumar, 1984; Pandey & Singh, 1989) report preference for need rule, other studies (e.g. Krishnan, 1998, 2000, 2001; Pandey & Singh, 1997) found equality or both need and merit as the fair choice of allocation norms.

Using a cross-national design, Cohn, White, and Sanders (2000) conducted a study in seven nations (Bulgaria, Hungry, Poland, Russia, France, Spain, and the USA) on distributive justice and procedural justice using vignettes to manipulate need and merit of the recipients and how fairly they were treated. They found support for their hypotheses which expected preference for need over merit in Central and Eastern European Nations due to their socialist experience, whereas the support for merit norm was more pronounced in Western nations.

Studies on value orientations across cultures (Hofstede, 1980, 2001; Abdullah, 1996) have placed Malaysians high on collectivism which has implications for this study. Collectivism puts emphasis on tight social organisation in which people clearly distinguish between in-groups. They expect the in-group to be concerned about their welfare and in exchange they are loyal to it. On the other hand, individualism refers to a social structure in which individuals are supposed to take care of themselves and their immediate family only. Malaysia ranks high among the top nations on collectivism (Hofstede 2001). This suggests that in a society high on collectivism, the allocation decision may be based on the recipient’s in-group characteristics.

Based upon the above discussions, it was expected that Malaysian collectivistic value should play a significant role in the choice of distributive justice norms and therefore it was hypothesised that:

Hypotheses

H/1

In a resource allocation situation involving a recipient with close personal relationship with the allocator (Brother) who is also meritorious versus another employee who is needy, equity rule is preferred, irrespective of the type of resource.

H/2

In a resource allocation situation involving a recipient with close personal relationship with the allocator (Brother) who is also needy versus another employee who is meritorious, need rule is preferred, irrespective of the type of resource.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 78 subjects from Kuala Lumpur Malaysia participated in the study (Male = 28; Female = 50). All had work experience and were enroled in the executive MBA programme. They belonged to several jobs and professional background and had a mean job experience of 4.43 (SD = 4.64) years. Their age ranged from 26 to 57 years (M = 28.84, SD = 7.54).

Design

The study involved a factorial design. The dependent variables were preference for allocation norms (equity, equality, or need) and perceived fairness of the choice of the allocation decision. The independent variables were (a) type of resource (money/material goods and favour) and (b) in-group/out-group status of the recipients (brother vs. another employee with no personal relation with the allocator). It also included a control group where no relationship between allocator and recipient was stated. The sample distribution in each of the resource distribution conditions is presented in Table 1.

Allocation rule preference was measured by describing resource distribution scenarios or vignettes. The scenarios included four resources, two each related to money (distribution of an award money and distribution of loan) and favour (grant of leave and nomination for foreign assignment). The scenarios included two recipients, one who deserved the resource (merit) and the other who needed that resource. Additionally, in the experimental conditions, one of the two recipients was described as brother of the allocator, while the other recipient was just an employee. In the control group, no relationship between allocator and recipients was mentioned. For example, in case of leave, the scenario described two persons who apply for 10 days of leave to the General Manager. Person A needs the leave because he has to prepare for an important examination. B’s application shows he qualifies for the leave by having worked extra hours during the previous weeks. Person A is brother of the GM. In group 2 scenario, description remains the same except that Person A (Brother) is mentioned as meritorious. Other vignettes followed the same pattern in manipulating the need versus merit and relationship status of the recipient.

Using a 5-point Likert scale, subjects were asked to indicate if they would give all to needy (anchor point 1), give more to needy (anchor point 2), divide the resource equally between the two recipients (anchor point 3), give more to meritorious person (anchor point 4), and give all to the meritorious person (anchor point 5). In each of the scenarios, subjects were also asked to rate, on a 5-point Likert scale, the degree of fairness of the decisions (1 = very unfair; 3 = neither fair nor unfair; 5 = very fair).

Procedure

Subjects were randomly assigned to the three groups. Each group received a set of printed questionnaire which described the four different scenarios (award money, loan, leave, and foreign assignment). Order of these four scenarios was randomised to control the order effect. While group # 1 received all four scenarios where bother was meritorious, in group # 2, scenarios described brother as needy. Group # 3 was a control group where no relationship status between allocator and recipient was stated. In order to minimise social desirability effect, subjects were asked to indicate their perception of the norms (equity, equality, and need) that are usually followed in their workplace and not how they would like to take decisions themselves in these situations.

Results

Figure 1 displays frequency graph of subjects by their perception of norms frequently used in their organisation in relation to the four resources being distributed between the two recipients. While granting a leave and nominating an employee for foreign assignment belonged to less tangible category of resource known as favour, award money and loan belonged to more tangible category, i.e. money or material goods. Figure 1 displays the frequency distribution of subjects.

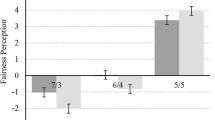

Table 2 presents mean, SD, and ANOVA results to test the significance of mean differences among the three groups on perceived allocation norms and fairness across four distribution situations.

Results showed (see Table 2) that perception of resource allocation norms and their fairness among three groups and across four allocation resources were not significantly different, as F values were not significant in all but one instance. In case of distribution of loan, there were perceived differences, though not highly significant, in the choice of norms (F = 2.596, p < .081), but the three groups were significantly different in their judgement of fairness (F = 4.587, p < .01). While group 1 was tilted towards need rule, group 2 was more for equality and group 3 was more for merit. The results are discussed in the following section.

Discussion

While there is no dearth of research studies on the issue of organisational justice and its antecedents and consequences, few studies have tried to examine the concept of justice enactment which may include the deliberate, conscious, and intentional actions of the decision maker to treat the recipients in either just or unjust manner. The resource allocation scenarios presented before the subjects of the study put them in situations where they had to make a conscious and intentional decision based on the merit/need as well as the relationship factors. The preferred norms of allocation decision were examined in relation to two types of resources, that is, money/material goods (tangible resource) and favour (intangible resource). It was hypothesised that relationship factor (in-group/out-group) will influence the allocation decisions and will override other considerations such as merit or need of the recipient. In other words, if the recipient is closely related to the allocator, such as a brother, then the norm that benefits the recipient will be preferred, irrespective of the fact that the other recipient is needy or has merit. This will apply in case of tangible and intangible resources.

However, the results did not support our hypotheses. Being a relationship-oriented and collectivistic society, it was expected that in-group status of the recipient will play a strong role in allocation decisions. However, no significant effect of relationship of allocator with recipient was found in the distribution of either money or favour as resource. The most frequently endorsed norm of distribution was equality, which seems to illustrate that in the Malaysian context balancing between merit and need is important. Nonetheless, preference for equality was more pronounced in the case of grant of leave and nomination for foreign assignment (both considered as favour and less tangible) compared to more tangible resources (award money and grant of loan). In the case of grant of loan, if one of the two recipient was the brother of allocator, merit received shade lower endorsement (mean = 2.77) compared to need (mean = 3.11). However, in the control group, merit received higher endorsement (mean = 3.67). Furthermore, the mean differences among the three groups on fairness rating were significant. Thus, as far as grant of loan money was concerned, merit overruled need when relationship factor was not introduced in the scenario. However, this was not the case in the two experimental groups where relationship factor was introduced. Thus, when contextual determinants are not accounted for, the result is in conformity with studies which suggested that in general equity is preferred in the distribution of tangible benefits (Leventhal, 1976; Otto et al., 2011). However, in the collectivistic culture or countries as well as nations with exposure to socialism, equal distribution of resources between needy and meritorious is considered fair (Leung and Bond 1982; Marin, 1981, Krishnan et al., 2009; Krishnan, 1998, 2000, 2001; Pandey & Singh, 1997). Drawing arguments from Krishnan et al. (2009) preference for equality in allocation decisions may reflect more than one mechanism or value. Reflecting on their findings on Indian sample, they observed that, “…it may indicate an egalitarian philosophy, the thinking that rewards and punishment must be distributed equally among individuals, without discriminations in terms of merit or need.” (p. 110). Equality norm may also indicate cultural norm in terms of concern for group rather than one individual, with emphasis on cooperation rather than competition. Furthermore, as Krishnan and her associates argued preference for equality norm may suggest that in collectivistic and relationship-oriented culture, people are prone to use a cognitive strategy where they combine merit and need rather than merit or need in their decisions. Thus, when making a choice between the three norms, people tend to integrate all the available information provided in the scenarios presented to them. That resulted into equality preference.

Conclusion, Limitations, and Suggestions for Future Research

The paper examined employees’ perception of norms of resource allocation and fairness in organisations. Taking two resource types (money and favour), it examined the effect of in-group–out-group characteristics of recipients on the choice of allocation norms. It was expected that in the relationship-oriented and collectivistic culture of Malaysia, where the study was conducted, the choice of norms will vary to suit the in-group recipient across types of resources being distributed. The results, however, were not in the expected direction. It was found that the choice of resource allocation norm was not significantly determined by the allocator–recipient relationship, nor types of resources made any difference. In most of the cases, equality was perceived as the most common practice and also rated fair. Nonetheless, there were shades of differences as well. The post hoc interpretation of the findings is based on the egalitarian philosophy embodied in collectivistic culture and the cognitive strategy of the subjects where they integrated rather than separated need and merit norms to perceive and rate equality as the most common and fair norm. However, this interpretation need to be further tested in a cross-national study with data from a non-socialist nation.

The research needs to further verify these conclusions using a much larger sample as well as some more factors that may influence resource allocation decisions such as self-interest of the allocator, power, and status of the recipients, etc. The relationship characteristics may be further expanded to include close vs distant family, friends, acquaintances, and strangers. A direct measure of cultural values as practised by the subjects of the study should add value to the conclusions.

References

Abdullah, A. (1996). Going glocal: Cultural dimensions in Malaysian management. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Institute of Management.

Aruna, A., Jain, S., Choudhary, A. K., Ranjan, R., & Krishnan, L. (1994). Justice rule preference in India: Cultural or situation effect? Psychological Studies, 39(1), 8–17.

Benton, A. A. (1971). Productivity, distribution, justice, and bargaining among children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18(1), 68–78.

Berman, J. J., Murphy-Berman, V. A., & Singh, P. (1985). Cross-cultural similarities and differences in perceptions of fairness. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 16(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220022002185016001005.

Chen, C. C. (1995). New trends in reward allocation preferences: A Sino-U.S. comparison. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 408–428. https://doi.org/10.2307/256686.

Deutsch, M. (1975). Equity, equality, and need: What determines which value will be used as the basis of distributive justice? Journal of Social Issues, 31(3), 137–149.

Fischer, R., & Smith, P. B. (2003). Reward allocation and culture: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 34(3), 251–268.

Giacobbe-Miller, J. K., Miller, D. J., & Victorov, V. I. (1998). A comparison of Russian and U.S. pay allocation decisions, distributive justice judgements, and productivity under different payment conditions. Personnel Psychology, 51(1), 137–163.

Greenberg, J., & Cohen, R. L. (1982). Equity and justice in social behaviour. New York: Academic Press.

Hassan, A., & Ahmed, K. (2001). Malaysian management practices: An empirical study. Kuala Lumpur: Leeds Publications.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviours, institutions, and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behaviour: Its elementary forms. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Hundley, G., & Kim, J. (1997). National culture and the factors affecting perceptions of pay fairness in Korea and the United States. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 5(4), 325–341.

Krishnan, L. (1998). Allocator/recipient role and resource as determinants of allocation rule preference. Psychological Studies, 43(1–2), 2129.

Krishnan, L. (2000). Resource, relationship, and scarcity in reward allocation in India. Psychologia, 43(4), 275–285.

Krishnan, L. (2001). Justice perception and allocation rule preferences: Does social disadvantage matter? Psychology and Developing Societies, 13(2), 193–219.

Krishnan, L., Varma, P., & Pandey, V. (2009). Reward and punishment allocation in the Indian culture. Psychology and Developing Societies, 21(1), 79–131.

Lerner, M. J. (1974). The justice motive: ‘‘Equity’’ and ‘‘parity’’ among children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29(4), 1–52.

Lerner, M. J., Miller, D. T., & Holmes, J. G. (1976). Meritorious and emergence of forms of justice. In L. Berkowitz & E. Walster (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 9, pp. 133–162). New York: Academic Press.

Leung, K., & Bond, M. H. (1982). How Chinese and Americans reward task-related contributions. Psychologia, 25(1), 32–39.

Leventhal, G. S. (1976). Fairness in social relationships. In J. W. Thibaut, J. T. Spence, & R. C. Carson (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 27–55). New York: Plenum Press.

Lin, Y. H. W., Insko, C. A., & Rusbult, C. L. (1991). Rational selective exploitation among Americans and Chinese: General similarity with one surprise. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 21(14), 1169–1206.

Mahler, I., Greenberg, L., & Hayashi, L. (1981). A comparative study of rules of allocation: Japanese versus American. Psychologia, 24(1), 1–8.

Marin, G. (1981). Perceiving justice across cultures: Equity versus equality in Columbia and United States. International Journal of Psychology, 16(13), 153–159.

Mikula, G., & Schwinger, T. (1978). Intermember relations and reward allocations: Theoretical considerations of affects. In H. Brondstaller, J. H. Davis, & G. Schuler (Eds.), Dynamic of group decisions (pp. 229–250). Beverly Hill, CA: Sage.

Murphy-Berman, V., Berman, J. J., Singh, P., Pachauri, A., & Kumar, P. (1984). Factors affecting allocation to needy and meritorious recipients: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(6), 1267–1272.

Otto, K., Baumert, A., & Bobocel, S. R. (2011). Cross-cultural preferences for distributive justice principles: Resource type and uncertainty management. Social Justice Research, 24(3), 255–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-011-0135-6.

Pandey, J., & Singh, P. (1989). Reward allocation as a function of resource availability, recipients’ needs, and performance. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 115(4), 467–481.

Pandey, J., & Singh, P. (1997). Allocation criterion as a function of situational factors and caste. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 19(1), 121–132.

Thibaut, N., & Kelley, H. (1959). The social psychology of groups. New York: Wiley.

Wu, T.-F., Cross, S. E., Wu, C.-W., Cho, W., & Tey, S.-H. (2016). Choosing your mother or spouse: Close relationship dilemmas in Taiwan and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 47(4), 558–580.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hassan, A., Ahmed, M. Fairness in Allocation Decisions: Does Type of Resource and Relationship Matter?. Psychol Stud 64, 103–109 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-019-00480-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-019-00480-8