Abstract

Arguments can be developed that the higher the degrees of economic development are, then the more likely it is that advanced economic development also requires the development of a democracy. In that respect, we can expect certain associations (or also a coevolution) between quality of democracy, knowledge democracy, and knowledge economy. So there is also a type of plausibility for the assertion of “democracy as innovation enabler.” Here, political pluralism and a heterogeneity and diversity of different knowledge and innovation modes should mutually support and reinforce each other. This can point in favor of a coevolution of democracy and a “democracy of knowledge” and of “democracy as innovation enabler”? The diversity (not only political diversity and political pluralism, but also knowledge and innovation diversity) within democracies may feed effectively into the next-generation creations of knowledge production and innovation system evolution, which will be necessary for progress and further advances of knowledge society, knowledge economy, and knowledge democracy in a global format

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

The analysis in this work was guided by the following two key research questions, which also structured the research and organization of research : How to conceptualize and measure democracy and the quality of democracy in global comparison ? As third (and complementary) research question we referred to the proposition (hypothesis) of “ democracy as innovation enabler .” This research interest resulted in conceptualizing and measuring the quality of democracy in a world wide approach. The empirical macromodel consisted of 160 countries that represented more than ninety-nine percent of the world population. This country reference included democracies and non-democracies (democracies , semi-democracies and non-democracies ). The empirically covered years were the fifteen-year period of 2002–2016. For that purpose also a specific conceptualization was developed. The basic quintuple-dimensional structure of democracy identifies five basic dimensions (basic conceptual dimensions ) for democracy and quality of democracy : freedom , equality , control , sustainable development and self-organization (political self-organization) (Sect. 1.2). Strictly indicator based on the country sample was referred to these dimensions. Particular emphasis was placed on the dimensions of freedom , equality , sustainable development and self-organization (government /opposition cycles as a manifestation of political self-organization). The empirical outcome of this endeavor is documented in an indicator-and-data format for all countries, all years and all dimensions (subdimensions) in the tables followed in Appendix (Appendices A.1–A.3).

The work here demonstrates that already it is possible to measure quality of democracy systematically and in a global comparison with the existing and publically available data and indicators, at least when the covered year period is set to start after 2000. The analysis is not limited and bound to democracies only, but can address democracies and non-democracies (democracies , semi-democracies and non-democracies ). In the case of non-democracies , the absence of quality of democracy can be demonstrated. With the comprehensive inclusion of non-democracies (in addition to democracies and semi-democracies ), this attempt of measuring quality of democracy converts the applied model into a world model, which is only constrained in case of missing data.Footnote 1 But even these data imperfections cannot question in principle the raised assertion of a world model for measurement of democracy and quality of democracy . Conceptualizations of quality of democracy , well grounded in theory and in discourses on democracy, can be designed and can be applied for practical inquiry. As conceptualization , which was the reference for our research , we proposed to introduce the basic quintuple-dimensional structure of democracy. Democracy measurement , based on theories and concepts of quality of democracy , can be achieved in contemporary context. For the coming years, this provides the further opportunity of a further co-development (“co-evolution ”) of theory of democracy and measurement of democracy , which appears to be necessary exactly in such an interlinked and cross-linked mode and approach. One practical aspect of the way how quality of democracy was conceptualized and measured in the framework of the work here is that it can be interpreted to result in a comparative multidimensional index-building for democracy (also degrees of democratization for all countries) in the world . Despite this ability of a global democracy measurement in contemporary context, supported by a reasoning based on a conceptual design development rooted in theory of democracy , still a paradox prevails. The consequences of democracy measurement also appear to present (to “produce”) ambiguities, puzzling empirical effects and trade-offs in the empirical results. For the analytical interpretation of outcomes in democracy measurement , often different and conflicting propositions can be suggested, where no easy balance or “solution” at a “meta-level” is in near sight. Shifts in a “conceptual position” lead to shifts in assessment. This may mean that we still do not fully understand how the dynamics of democracy development is unfolding and evolving on a global scale. This also underscores, why it is so difficult to address “Why Questions” of democracy and quality of democracy in a meaningful (and non-trivial) way.

In the following, the conclusion is structured in three sections. In the first section, global trends for the dimensions of freedom and equality are summarized. Section two, in the format of an outlook, formulates hypotheses for further research on democracy and quality of democracy in a world wide format. Section three, finally, engages in a short resume.

7.1 Conclusion: Summary of Comparison of Countries and Country Groups Over the Dimensions of Freedom and Equality (2002–2016)

In this section, we again summarize in a focused approach the results when comparing the different countries and country groups across the dimension (basic dimensions ) of freedom and equality . The dimension of freedom is being specified into the following two dimensions (subdimensions): political freedom and economic freedom . The dimension of equality (here) distinguishes between two dimensions (subdimensions): income equality and gender equality . There always can be (and probably always will be) a serious discussion and by this a (potentially) conflicting discourse, what the essential and underlying dimensions of democracy and quality of democracy are. Depending on the specific theory or conceptual approach, there may be disagreement (for an overview of theories and models of democracy see: Cunningham 2002; Held 2006; Meyer 2009; Schmidt 2010; Sodaro 2004). For clarification in discussion, it may be appropriate to distinguish between basic and non-basic (so-called secondary) dimensions of democracy. Basic dimensions should be regarded as being essential for democracy, while in the case of non-basic (secondary) dimensions there can be a greater amount of discussion, but also higher degrees of dissent, whether these qualify or should qualify to be crucial for democracy, crucial for our understanding of democracy and crucial for the quality of democracy .Footnote 2 There appears to be a widespread consensus (at least in discourses in Europe , the USA and North America ) that freedom and equality represent two decisive basic dimensions of and for democracy and the quality of democracy . Without sufficient forms or degrees of freedom and equality , a political system does not qualify to represent a democracy. This assertion and proposition becomes complicated by several additional considerations: (1) freedom as well as equality already are broad categories or dimensions. The challenges arises, how to define freedom and equality further, to support a more precise approach of analysis. Within the model and framework of analysis, being applied here, the decision was made to distinguish between political and economic freedom , and between income and gender equality (see Sect. 1.3 and Chapter 2). (2) Furthermore, there can be trade-offs and contrary trends, developments and movements between freedom and equality as a whole, or also between subdomains or subdimensions of freedom and equality . For example, economic freedom and gender equality may improve, political freedom may stagnate and income equality even decline. How should such possible trade-off developments be evaluated and assessed comprehensively, are there options to initiate and again create a more balanced picture at a meta-level, or does this create paradoxes and puzzles that cannot be solved (at least not with rational means)?

In Sect. 1.2, based on a review of the traditional (classical) as well as recent literature on democracy and democracy research , we proposed to speak of five basic dimensions that define, underlie and create democracy and quality of democracy . These dimensions are:

-

1.

freedom ;

-

2.

equality ;

-

3.

control ;

-

4.

sustainable development ;

-

5.

and (political ) self-organization.

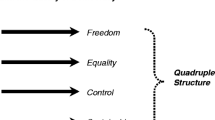

The two most basic dimensions of democracy are freedom and equality . Freedom , equality and control represent an arrangement of dimensions, favored by several authors (see Lauth 2004, pp. 32–101; Democracy Barometer 2013).Footnote 3 O’Donnell (2004, pp. 11–13, 42) draws the connection between human rights and human development . It can be convincingly argued that human development can be reinterpreted as a manifestation of sustainable development . The performance of the non-political dimensions, in context of the Democracy Ranking (Campbell 2008, pp. 32–34), serves as another example, which can be interpreted and reinterpreted in terms with sustainable development .Footnote 4 An explicit reference to sustainable development as the fourth dimension of and for democracy and the quality of democracy was made by Campbell (2012, pp. 296, 301–302, 306). These four dimensions together (and put into interplay, combination and overlap) can be discussed as the “Basic Quadruple Dimensional Structure” of democracy and the quality of democracy , by this also producing a “Quadruple Helix Structure of the Basic Dimensions ” of democracy (Campbell and Carayannis 2013).

Should self-organization (political self-organization) be added as a fifth basic dimension to democracy, also for the purpose of explaining democracy and the quality of democracy , then the conceptual consequence for theory would be that the conceptual complexity of and for democracy would increase. What results is a Basic Quintuple-Dimensional Structure of democracy and the quality of democracy , which again could be conceptually converted into a Quintuple Helix Structure of the Basic Dimensions of democracy and the quality of democracy .Footnote 5 One manifestation for political self-organization is political swings in form of government opposition cycles. In context of the framework of analysis being provided here, our applied model of conceptualization and measurement of democracy in global comparison focused on the dimensions (basic dimensions ) of freedom , equality and sustainable development , and already to a lesser extent on political self-organization (political swings ). No particular emphasis was placed on the dimension of control . However, we should add that the conceptual boundaries between these dimensions are not always sharp, but in fact overlap, and are furthermore subject to different and conflicting interpretations. Political swings , for example, can be assigned to the dimension of political self-organization, but also to the dimension of control .

In the previous chapters to the empirical model (Chapters 2–6), a major emphasis of analytical focus was placed on the basic dimension of sustainable development , and how countries (democracies , semi-democracies as well as non-democracies ) perform and develop (have developed over time) in relation and relationship to this analytical reference. In this Sect. 7.1, we focus now on the dimension of freedom (political freedom and economic freedom )Footnote 6 and the dimension of equality (income equality and gender equality ) that define as well as represent the two basic dimensions of primary and pivotal importance for democracy and the quality of democracy . By this we again engage in a more classical view or perspective, by this in accordance with a traditional understanding and theoretical understanding of democracy, which has been recently challenged by the importance of sustainable development . It is the global world perspective that has brought sustainable development into play. For the comparison in this section, we rerun several of the countries and country groups to which we already referred to in our more detailed (year-specific) comparison in the previous chapters (and sections). In the following comparison here, we created averages (means) for the whole seven-year period 2002–2016. Thus, the now discussed data do not plot trends, but display, on the other hand, a more stable and robust picture of relationships.Footnote 7 The following propositions are being supposed for further discussion:

-

1.

Comparison of the USA and the European Union ( EU15 , EU28 ) in relationship to the dimensions of freedom and equality (2002–2016): The USA can be compared directly with individual European countries, also member states to the European Union . This certainly represents a legitimate procedure. Of course, there always can concerns be raised, what the proper level (unit of analysis) would be, when comparing the USA with the European Union : (1) USA versus European countries; (2) US states versus European countries; (3) or USA versus EU ? This matrix of options even could be extended. Concerning the European Union , there also can always be a debate, whether the EU15 or EU28 would qualify as a better and fairer candidate for a comparison with the US regarding history, path trajectory and path-dependent development , the EU15 is more similar to the USA and has faced circumstances, which make a direct comparison easier. For example, Eastern-Central Europe , now a major region within the EU , had suffered for decades under insufficient communist policy regimes and limited sovereignty within the imperial sphere of influence of the Soviet Union. At the same time, however, it must be mentioned and underscored that the European Union (in its institutional manifestation) does not exist as EU15 , but only as EU27. In that respect, the EU15 represents also an analytical narrowing-down, deviating from real-world institutional settings. When comparing the USA (alternatively) with the EU15 and EU27, the following impressions can be drawn:

-

(1)

USA and EU15 : Concerning political freedom , the EU15 leads marginally, with regard to economic freedom , the USA has a substantial lead. Concerning again gender equality , the EU15 again leads marginally, with regard to income equality more substantially (see Fig. 7.1). Are the two freedom and equality dimensions being aggregated together into one freedom and equality dimension, then the USA leads in the sphere (domain) of freedom , and the European Union leads in the sphere (domain) of equality (see Fig. 7.2). This means that the EU15 performs better with regard to equality , more so in reference to income equality , less so in reference to gender equality . So the comparative quality of democracy in the EU15 focuses more on equality , when compared with the USA. The USA only achieves a split lead with regard to freedom . The USA leads in reference to economic freedom , but lags marginally behind the EU15 in reference to political freedom . Particularly this lagging behind EU15 with regard to political freedom is interesting.Footnote 8 The more of equality in Europe (EU15 ) did not constrain a performance (good performance) in political freedom . The non-lead in freedom by the USA is contrasted by the already-lead (yet-lead) of the European Union ( EU15 ) in equality . All together, it appears that the EU15 mobilized a comparative aggregate advantage over the dimensions of freedom and equality , when placed into a direct comparison with the USA (and for the period of time of 2002–2016). In that sense, the American model of democracy and quality of democracy is being seriously challenged by the European model (models) of democracy and their quality . So it cannot be said that the comparative quality of American democracy, when compared with EU15 , is per se freedom . However, it should be added that the lead of the EU15 over the USA is only very tight and thin in the dimensions (subdimensions) of political freedom and in gender equality , so we cannot really speak here of a hegemony in quality in favor of the European Union . Despite the proposition that the EU15 realized competitive quality -of-democracy advantages in equality , there results also the (competing) picture of a deadlock or stalemate, when compared with the USA, because the progress of the EU15 is only marginal in two dimensions (subdimensions). So the ambiguity and puzzling effect would be the assertion that there does not exist a clear-cut picture, whether the EU15 has advanced further than the USA with regard to quality of democracy . Patterns of lead are fragile, and perhaps (but not necessarily) may shift in future.

Fig. 7.1 -

(2)

USA and EU28 : For the comparison of the USA with EU15 , the one (contested) conclusion was (is) that the EU15 leads in both dimensions (subdimensions) of equality , while with regard to freedom , there is a split situation: the (small) lead of EU15 in political freedom is being contrasted by a clearer lead of the USA in economic freedom . All together, however, it appears that the advantages (on grounds of quality of democracy ) are more with EU15 . Is the focus of analysis extended and broadened from EU15 to EU28 , then the advantages move and gravitate more in favor of the USA (see Fig. 7.3). Within the framework of comparison of the USA versus EU28 (in the time frame 2002–2016), the following patterns are manifested: the USA leads marginally on political freedom and substantially on economic freedom , and the USA leads furthermore marginally on gender equality , while the EU28 lies ahead in income equality . By this, income equality represents the only dimension (subdimension), where EU27 realizes an advantage, when put in contrast to the USA. Are the two dimensions (subdimensions) of freedom (political freedom and economic freedom ) as well as of equality (gender equality and income equality ) aggregated together into one meta-dimension of freedom and equality , then the USA places ahead in context of freedom , but EU28 is in the forefront of equality (see again Fig. 7.3). Summarized and summarizing propositions therefore are: (a) is the conceptualization of democracy and quality of democracy being based on freedom and equality , then the overall advantage, competitive advantage, leans marginally in favor of the USA. This US lead is clearer in freedom , while in equality we are confronted with a split situation, with a slight advantage of the USA on gender equality , whereas the EU28 lies evidently ahead in income equality . (b) By tendency, there are structural similarities in the dimensional profile of EU28 and EU15 . But despite this asserted structural similarity, the EU28 lags behind EU15 in all dimensions (subdimensions) of freedom and equality . On these grounds, and when based on the dimensions of freedom and equality , it appears that quality of democracy has developed to a higher degree in EU15 than in EU28 . Still, differences in scores between EU15 and EU28 are only minimal. This minimal drawback of EU28 , however, is sufficient, to place EU28 behind the USA on several of the measured dimensions.

-

(3)

USA versus EU15 or EU28 : The remaining ambiguity now of course is to decide or wanting to decide, whether EU15 or EU28 represents a better (fairer) comparison for the USA. The dilemma here however is that this cannot be decided on neutral grounds. The pros and cons arguments work in both ways or either ways. In one understanding, this even could have the consequence of going so far as to assert that it cannot be really decided, whether the USA or the European Union is leading or has realized a competitive advantage with regard to freedom and equality . Unquestionable is only that the USA is placing ahead in economic freedom , and the European Union leads in income equality . Political freedom and gender equality , on the contrary, do not allow for a final and stable comprehensive assessment. Differences in scores for political freedom and gender equality are so tight, by this making stable predictions for the coming years almost impossible. In political (also ideological) terms, we are caught in the dilemma that an analytical reasoning cannot really prove, whether American or “ European democracy”Footnote 9 has developed or evolved to higher levels of quality of democracy . This bounces back as a puzzling effect into our discourses and theories on democracy and quality of democracy . The “neutral” and “really convincing” meta-perspective (point of reference) for a comparison of the USA and the European Union on the basis of freedom and equality was not found, not found in the sense of being able to make an ideologically neutral assessment and statement. Within the framework of analysis and model, being applied here, it cannot be verified whether quality of democracy in the USA or EU is on the winning side when pooling freedom and equality together as the decisive benchmark, at least a finally convincing statement is not possible, and would be premature (perhaps even be ideologically biased). What results (so far) is a situation, where propositions can be formulated that argue and reason in favor of the USA, but also in favor of the European Union . The spectrum of competing and contradictory interpretations is still wide, and there is enough room and space for divergent and deviating assessment. Ideology can use this “open space” of academic research and reasoning to emphasize interpretations in either way. Perhaps this open answer does not satisfy. Perhaps we reach here limits of our current concepts and theories about democracy, which were also not transcended by our research on advanced democracy.

-

(1)

-

2.

Comparison of the USA and the Nordic countries in relationship to the dimensions of freedom and equality (2002–2016): When the USA is compared with the Nordic countries over the dimensions (subdimensions) of freedom and equality , then the USA is leading with regard to economic freedom (see Fig. 7.4). The Nordic countries lead in political freedom , gender equality and in income equality . The saliency and advantage of the Nordic countries in income equality are substantive and paramount. The lead of the Nordic countries in political freedom and gender equality is not that dramatic anymore, but still clear, and in that sense also stable. Are the two dimensions (subdimensions) of freedom and equality being aggregated into one meta-dimensions of freedom and equality , then we are facing the following empirical situation: the USA is leading only marginally in freedom ; however, the Nordic countries express a substantial leadership in equality . Based on this empirical patterning, the following propositions are being offered as a guidance for interpretation Fig. 7.5:

Fig. 7.4 Fig. 7.5 -

(1)

When quality of democracy (the concept of quality of democracy ) is being rooted primarily in freedom and equality , or the dimensions of freedom and equality , then it appears that quality of democracy has evolved to higher levels of quality in the Nordic countries than in the USA. Such an asserted lead of the Nordic countries over the USA in ( freedom -based and equality -based) quality of democracy does not represent a biased ideological assertion, but can in fact be measured and displayed in empirical terms. This is particularly the case, should there be an aggregate understanding of quality of democracy , when the different dimensions (subdimensions) of freedom and equality are pooled and are aggregated into on comprehensive statement of assessment. The USA leads only with regard to economic freedom , but here concerns could be raised, whether economic freedom measures adequately the quality of a democracy. There is more of a consent that political freedom , gender equality and income equality associate more clearly with quality of democracy . Therefore, not the USA, but the Nordic countries represent a more advanced and competitive benchmark for quality of democracy in the world . The Nordic countries demonstrate to the world , which levels of quality of democracy already are possible, can already be realized in empirical terms (see also Campbell et al. 2012, pp. 172–173).

-

(2)

The lead and leadership of the Nordic countries over (ahead) of the USA is in the dimension (subdimensions) of equality even more pronounced than in the dimension (subdimensions) of freedom . The Nordic countries progressed furthest in equality , but also in combination with a lead in political freedom . The Nordic countries express a well-balanced progress in equality as well as in political freedom . Equality , particularly income equality , represents the most vulnerable “flank” of American democracy, while the USA could not realize an advantage in political freedom over the Nordic countries , or even the EU15 . So what is the worth or value of economic freedom in democracy of the USA, when this does not yield more results or more progress in political freedom , gender equality and income equality ?

-

(3)

The proposition can be formulated and be put forward for discussion that the Nordic countries represent perhaps the highest developed and most advanced region world wide and globally in terms of freedom and equality and in terms of a combination of freedom and equality . Do the Nordic countries demonstrate the highest standards of a freedom -based and equality -based quality of democracy in the contemporary world ? Our analysis (in context of our framework of analysis and applied model) suggests this conclusion (see later also Figs. 7.6 and 7.7). In that sense, there exists a “Nordic model” (Carayannis and Kaloudis 2010, pp. 10–15), which should be carefully analyzed, with a need of careful evaluation what could be learned by other countries from the Nordic countries . There are other single countries that can compete in this respect with individual Nordic countries , for example Switzerland (Campbell et al. 2012, pp. 172–173). The emphasis here, however, is not so much placed on the individual Nordic countries , but on the Nordic region as a whole. Here the concept of a “region,” by definition, implies to incorporate several (neighboring) countries into one cluster. In that understanding, Switzerland is a country, but not a region. Our formulated proposition addresses the Nordic countries as a region and does not refer to the individual Nordic countries separately. Remaining challenges are: (a) What can the Nordic countries learn from the other countries? (b) How representative are the Nordic countries for developments in global context, or do the Nordic countries (out of which reasons whatsoever or whatever) represent a very privileged world region, with exceptional conditions, which do not allow comparisons (for strategy and policy learning) with other countries or world regions? (c) To which extent can the Nordic countries uphold and sustain their lead in freedom and equality , or are also scenarios of a decline possible?

Fig. 7.6 -

(4)

This lead of the Nordic countries , however, does not allow the conclusion or assertion of a lead of European democracy in general in freedom and equality over the democracy and quality of democracy in the USA. Based on freedom and equality , the Nordic countries place ahead of the USA as well as ahead of the European Union (averages for EU15 , but more so for EU28 ). The European Union , as well as the USA, lag here clearly behind the Nordic countries (see again later Figs. 7.6 and 7.7). American democracy and European democracy must learn from democracy in the Nordic countries . Therefore, not only the USA, but also most of the member countries of the European Union , should assess carefully, what lessons are to be learned from the Nordic countries , in order to improve their quality of democracy at home. In conceptual and methodic terms, this comparison between Nordic countries and the European Union (EU15 , EU28 ) is complicated by the circumstance that with the exception of Norway, a majority of the Nordic countries (Denmark, Sweden and Finland) are also member countries to the European Union .

-

(1)

-

3.

Comparison of the OECD countries with the whole world ( world average) in relationship to the dimensions of freedom and equality (2002–2016): The OECD countries represent, by and large, the advanced (most advanced) economies in the world and represent furthermore (by and large) advanced societies and advanced democracies . By tendency, the OECD countries are also examples for knowledge economy , knowledge society and knowledge democracy , meaning that knowledge (knowledge and innovation ) are important drivers for their performance and progressive evolving. For us, this should serve as a (simplified) point of departure for further analysis and discussion. In all dimensions (subdimensions) of freedom and equality , the OECD (here OECD35) is leading ahead of the world , the world average (here World 122).Footnote 10 The lead of the OECD is the largest in freedom , in political freedom even larger than in economic freedom , but on the dimensions of equality , this OECD lead already is considerably smaller (see Fig. 7.5). In context of our analysis, we proposed to interpret the Nordic countries as the most advanced world region in quality of democracy in terms of freedom and equality . There is a gap world wide in favor of the OECD , when compared with the world average, and based on freedom and equality . This gap even is bigger and considerably even wider when the world average is being compared with the average of the Nordic countries (see Figs. 7.6 and 7.7). By and large, the USA and the European Union ( EU28 ) occupy an intermediate position between the Nordic countries and the average for the OECD countries, with a few exceptions. These exceptions are: the EU28 performs weaker in economic freedom , but still ahead of the world average. The USA performs dramatically weaker on income equality . In fact, the USA scores on income equality lower than the world average, which is quite unusual for an OECD country or an advanced economy , by this representing a case of under-performance even in global comparison and context (see again specifically Fig. 7.6). Based on the comparison of the OECD with the whole world (average) across the dimensions (subdimensions) of freedom and equality , the ambiguity arises that we are confronted with some puzzling effects. In fact, two different interpretations, narratives can be suggested for further discussion (see again Fig. 7.5):

-

(1)

In terms of freedom , the OECD countries lead clearly ahead of the world average. This is the case for economic freedom , and even more so for political freedom . This is an important empirical evidence for the proposition that there are patterns of an association and congruence between democracy ( quality of democracy , political freedom ) and advanced economies and advanced societies. This supports the assertion of a co-evolution between democracy, economy and society , or between advanced democracy, advanced economy and advanced society . The crucial key implication of this is that beyond a certain threshold a further development of economy and society is not possible (or is not likely), without the establishment and progress of a democracy. Co-evolution of democracy , economy and society should also be understood and conceptualized as a key expression and key manifestation of sustainable development : here, the concepts and basic dimensions of freedom , equality and sustainable development come together and overlap. Of course, what these thresholds are may not be clear in advance, there can be “fog” in that zone. Depending on a series of circumstances, there can be a variability of the width of that spectrum. For example, authoritarian or totalitarian regimes can learn and can try to implement innovations that were explored and developed by democracies , without establishing a democracy, by this attempting to bypass democracy and political freedom . In the long run, however, and so the proposition here, such a strategy of authoritarian or totalitarian regimes is doomed to fail, blocking progress and further development into higher and advanced stages. For example, it is difficult to perceive how China wants to continue its impressive track record of current economic development , without allowing and introducing more political freedom , and a process of democracy establishment and democratization as a final consequence and in final consequence of ultimo ratio.

-

(2)

Despite this impressive lead in freedom ( economic freedom , even more so in political freedom ) of the OECD over the world ( average), the OECD lead in equality ( gender equality , but again more so for income equality ) is already much smaller, to a certain extent perhaps surprisingly marginal. This, of course, refers to a series of very critical question. Why did progress in freedom not align with more substantive progress in equality ? The OECD countries (by and large) are also more advanced economically and socioeconomically than the world (average). Was it that progress (economic progress) aligned more clearly with freedom , to the disfavor of equality ? Was there an uneven and unbalanced dynamics in development , with improvements in freedom , and stagnations or declines in equality ? Is there a “negative correlation” between freedom (freedom and economic progress) and equality ? Were gains in freedom and economic progress at the price of equality ? Levels of wealth are clearly higher in the OECD countries than in the rest of the world . This shows up when indicators are being taken into consideration such as GDP per capita . However, degrees of equality are not necessarily higher, or much higher, when placed comparatively to the extent of leads that have been established in dimensions or domains of freedom . The ambiguity and puzzling effect of course is: What counts more, what weighs more, levels of wealth or degrees of equality ? Also: What are the thresholds, from where further declines in equality seriously can endanger progress in freedom and economy , can start eroding democracy or the base of democracy, pulling down quality of democracy ? Within equality , we apparently are facing a particular pattern of equality or inequality : there may be more of a gender equality (also better prospects for future improvements in gender equality ), but perhaps less in income equality , meaning that inequality is more based on income inequalities. Income inequality represents perhaps the bigger problem in context of equality . Here, we encounter a “vulnerable flank” of the advanced economies in the OECD countries and may touch upon the “Achilles tendon” of progress how it was established and practiced in the Western systems of capitalism or market economy . Our framework of analysis and applied model provided the capability and capacity to identify those sensitive questions and ambiguities and puzzling effects about the moving and dynamic relationship between freedom and equality (freedom , equality and economic progress); however, at least for the moment, we are not in a position to offer the final or further reaching answers. It may be that the relationship between freedom and equality (and progress) has been under-researched in the past, or that also the epistemic understanding of the underlying forces is under-developed or not sufficiently comprehended. Should there be an uneven development of freedom and equality in context of economic progress and economic advances, what are possible meta-references, for trying to foster a balanced (rebalanced) understanding and approach that could inform theory and practice?

-

(3)

In epistemic terms, there may also be the possibility that we still do not sufficiently understand what the differences are how indicators of freedom or of equality behave. It could be that (for whatsoever reasons) some indicators, subdimensions or dimensions of freedom express more of a variability (flexibility) than indicators or dimensions in equality . One consequence of this could be that countries place closer together in equality than in freedom . Would this pose analytical consequences on our reasoning about democracy and the quality of democracy ?

-

(1)

-

4.

Comparison of the Latin America with Asia ( Asia 15) in relationship to the dimensions of freedom and equality (2002–2016): Latin America is leading ahead of Asia (Asia 15) in both dimensions (subdimensions) of freedom , political freedom and economic freedom (see Fig. 7.8). The gap in political freedom , to the advantage of Latin America , is dramatic and considerable. Furthermore, Latin America places ahead of Asia in gender equality , but here the difference is more tightly in character and structure. Asia , on the other hand, leads ahead of Latin America in income equality , with a dramatic gap to the disadvantage of Latin America . Are both dimensions (subdimensions) of freedom and equality being aggregated together into one meta-dimension of freedom as well as equality , than an advantage results to the favor of Latin America in freedom , concerning equality , however, the advantage is with Asia . Are democracy and the quality of democracy being conceptualized on the basis of freedom and equality , then the overall picture appears to be that democracy has evolved further in Latin America than in Asia (now assessed as whole world regions). Furthermore, it would have to be added that democracy is only possible, when “minimum” levels (minimum thresholds) of political freedom have been established. The lower scoring of Asia on political freedom , therefore, constitutes per se a problem for being typologized or for qualifying as democratic political systems or democratic regimes of governance . Not only is Latin America leading in political freedom and economic freedom , but also in gender equality . However, a major concern for Latin America appears to be the dramatically greater extent of income inequality , when compared with Asia . Income inequality poses a risk and threat for the futures prospects of development for Latin America , for the futures of democracy in Latin America . Sustainable development in Latin America would require that a greater concern and emphasis is being placed on issues in relation to income equality . Lower levels of income equality mark in addition some structural similarities between Latin America and the USA (compare Fig. 7.8 with Fig. 7.6). Asia , as a whole world region, is challenged to introduce or allowing to introduce more political freedom . Within Asia ( Asia 14), there is of course a very diversified and mixed picture, concerning the established degrees of political freedom . In several countries (or states) within Asia , levels of political freedom perform comparatively low, implying that these countries (states) do not represent democracies . The comparison of Latin America and Asia (Asia 14) cumulates in the following ambiguity and puzzling effect: Latin America represents a region, where freedom and development co-evolve. Asia represents a region, where development frequently evolves without (with lower levels) of freedom . Does Asia , do some Asian countries (states) allow the assertion that there can be development (economic development ) without democracy? If so, would this fundamentally challenge some of the underlying beliefs and assumptions in Western societies? This creates the contradiction of development with freedom ( political freedom ) versus development without freedom ( political freedom ). Which model, which model of development , will prevail in the long run? Is it that degrees of freedom (political freedom ) are being systematically overestimated for Latin America and the individual countries in Latin America (by the sources used for the model in the applied framework or analysis here)? At the same time, there are certain expectations that in the long run, it would be difficult for Asia to continue its path and progress of development (economic development ) without inviting more political freedom and political processes of democratization : this would be particularly the case, when individual Asia countries encounter specific levels of medium or more advanced development . However, may this be an assumption, rooting more in ideology than in academic research reasoning? But we also must be cautions in developing too simplified propositions about Asia , because within the whole region of Asia we are confronted with different models of development and relationships of development and political freedom . China expresses lower levels of political freedom , while India developed higher levels of political freedom . Therefore, already within the context of Asia , we can observe this split and contradiction of development with political freedom versus development without political freedom (or development with lower levels of political freedom ). Beyond these ambiguities, of course, we should also ask, what is it that the regions of Asia and Latin America can learn from each other?Footnote 11

-

5.

Comparison of China , India and Russia (Russian Federation) in relationship to the dimensions of freedom and equality (2002–2016): Based on the dimensions (subdimensions) of freedom and equality , the biggest difference between China and India is manifest in the dimension (subdimension) of political freedom , with comparatively higher levels of political freedom in India , and comparatively lower levels of political freedom in China . This allows classifying India as a democracy, however, does not allow classifying China as a democracy. With regard to economic freedom , scoring in China and India is almost at equal levels. China has an advantage in gender equality , but India has an advantage in income equality (see Fig. 7.9). When being pooled together into one meta-dimension of freedom , and one meta-dimension of equality , the assessment would be: a split picture and situation for equality , but a gap in freedom to the advantage of India (see again Fig. 7.9). Therefore, an evaluation, based only on the dimensions (subdimensions) of freedom and equality (and leaving out other considerations such as performance and development in non-political dimensions or non-political indicators), could arrive at the following conclusion, or proposition for discussion: a freedom -based and quality -based comparative assessment of India and China places India ahead of China . In that sense, democracy and quality of democracy in India have evolved to higher levels than in China . Should this two-country comparison of India –China be extended to a three-country comparison of India –China –Russia (Russian Federation), then we can set up the following propositions for discussion (see Fig. 7.10)Footnote 12:

Fig. 7.9 Fig. 7.10 -

(1)

The greatest difference between these three countries focuses on the dimension (subdimension) of political freedom . The comparatively much higher scoring for India is being contrasted by a much lower scoring for China . Russia places itself in between, between India and China . Should the source (Freedom House ), which was used here for constructing the dimension of political freedom , be acknowledged as trustworthy, then the implication of this would be to interpret India as a democracy, and China as a non-democracy. The problem arises, how to categorize Russia ? Russia may be qualified as a semi-democracy, or as a non-democracy.

-

(2)

Scoring on economic freedom is remarkably similar between India , Russia and China . To a certain extent, it represents a puzzling effect that these greater differences in political freedom did not also translate into greater differences of economic freedom . Is economic freedom independent of the degree of political freedom or the degree of political authoritarianism? How is it possible to have economic freedom without political freedom ?

-

(3)

Differences in equality are greater than differences in economic freedom , but still lesser than in the case of political freedom . In equality , Russia lies always ahead of China . In gender equality , Russia lies ahead of China and India . In income equality , India ranks first, Russia second and China third.

-

(4)

When both dimensions (subdimensions) of freedom and equality are being aggregated and being pooled together into one meta-dimension of freedom and equality , interpretations then are: concerning equality , Russia , China and India lie and position together quite closely. But there is more of a variation with regard to freedom . Differences between India , Russia and China , therefore, are not so much constituted by equality , but are being created by differences in freedom . To be more exact, it is the political freedom and varying levels of realization of political freedom that make the differences between India , China and Russia . Political freedom drives here the key cleavages and defines and draws the crucial lines of distinction. To use and employ a metaphor: greater equality in equality is being contrasted by greater inequality in freedom . Could this be developed further to a general statement about emerging economies and Newly Industrializing Countries, or what are the serious limitations (and falsifications) to such a proposition?

-

(1)

7.2 Outlook: Formulation of Hypotheses for Further Research on Democracy and Quality of Democracy in Global Comparison

With our conceptualization and measurement of democracy and quality of democracy in global comparison , and their possible relationship to “democracy as innovation enabler ,” we entered new analytical territory. Therefore, we proposed to suggest that our analysis is more “explorative” in character (see Fig. 1.3 in Sect. 1.1). Because of this, we did not develop “ex-ante” hypotheses that guided our research and were set in contrast to research results. There was the impression that this may be to too early at that stage and on the basis of the conceptualization and framework that we wanted to employ (see Sects. 1.2 and 1.3). However, the idea was that in reference to the empirical results, finally and in an “ex post” approach, several hypotheses on democracy, democracy development and quality of democracy should be formulated, designed and put forward for discussion. This is exactly what we approached and intended to achieve in this section. In the following, we formulate hypotheses for further research on democracy and quality of democracy in global comparison with possible ramifications for “ democracy as innovation enabler. ” These hypotheses reflect on the outcome of our research carried out in the work here. These hypotheses we furthermore suggest to be discussed for the progressing democracy research . By this, these hypotheses may be regarded to enter as possible “input”-propositions (input-hypotheses) the coming discourses on democracy and quality of democracy . We cannot rule out that between some (several) of the following hypotheses there may be “tensions,” perhaps even the potential of an analytical conflict and analytical contradiction, depending on the referred to viewpoint. This has to do with the circumstance that (at least in our view) the approach of empirical democracy measurement in a world wide format also produced ambiguities, puzzling empirical effects and trade-offs in the empirical results. We still face the problem and challenge of creating an overall “consistent picture” of democracy, democracy development and quality of democracy at a “meta-level,” when we want to assess democracy in global terms. There are chances that this “consistent picture” of democracy perhaps will never be achieved. Democracy could imply to be accompanied by a pluralism of diverging and contradicting reflections on democracy. Therefore, the following hypotheses were developed in a “fog of uncertainty.” Because of this, also these hypotheses should be regarded to be somehow “explorative” in character and must be exposed to serious discussion, whether or not they have potential for informing future democracy research .

The hypotheses refer to reflect on and interpret the results of the empirical macromodel,Footnote 13 where we plotted and analytically arranged 160 countries (for the years 2002–2016) in accordance to the dimensions (and subdimensions) of conceptualization of the basic quintuple-dimensional structure of democracy (see Fig. 1.7 and Sect. 1.2). Our empirical macromodel has two specific limitations that we want to address here shortly: Particularly for the dimension of freedom , we referred to “freedom indices” that were provided, but also constructed, by specific sources. In the case of political freedom , we took “political rights,” “civil liberties” and “freedom of press” of Freedom House (2013a, c). For economic freedom , we averaged “Index of Economic Freedom ” (Heritage Foundation 2013) with “Economic Freedom in the World ” (Fraser Institute 2009). To a somewhat lesser extent, this index approach was also the case for gender equality , where we relied on the Global Gender Gap Index supplied by the World Economic Forum (Hausmann et al. 2009) (see Fig. 1.10 in Sect. 1.3). One underlying rationale here for our democracy measurement project was to use data (indicators) that already exist, are publicly accessible (via the internet) and represent something like an “official world view,” not in the sense that these data (indicators) are uncontroversial, but in the sense that there are frequent references (citations) of these data (indicators). Possibly critical research results, based on such “official” data (indicators), would weigh then much heavier in discourse and public political debate. For empirical research , based on these indices, the implicit and inherent methodic problem here of course is: Do differences in research outcome reflect differences in reality and/or are they the specific consequence of how these indices are being constructed? Our dilemma is that we do not have a general and clear answer for that concern. We never can rule out for sure, not to have been captured by methodic particularities in the index construction (without even knowing or being aware of this). This poses a permanent ambiguity. Because political freedom represents such an important dimension (subdimension) for democracy and quality of democracy , we invested considerable efforts attempting to “validate” the freedom ratings of Freedom House (2013a, c), by comparing these with government /opposition cycles . We were successful in providing at least a partial validation of Freedom House (at least in our view). We could demonstrate that the higher the freedom rating by Freedom House , then the more of a likeliness there is that frequencies of a peaceful person and party change of the (de facto) head of government also will increase (see Fig. 6.3 and Table 6.6 in Chapter 6). (2) The years we covered were the years 2002–2016. We started with the year 2002, because Freedom House (2013a) initiated only to publish the more differentiated “aggregate scores” of political rights and civil liberties exactly with the year 2002. We ended our time series in 2016, because this was the last year with available comprehensive data and indicator information, when we processed the major data retrieval in the fall of 2017. Therefore, all hypotheses that we have formulated refer specifically to the fifteen-year period of 2002–2016. We reflect on patterns and trends in that time interval. Are there changes (will there be changes) in the global trends of democracy and quality of democracy after 2016? Within the conceptual and methodic framework of our empirical macromodel in context of the work here, we cannot address this question sufficiently. Seen from a personal viewpoint, it would appear to be unlikely or at least surprising if everything would change in the years after 2016. However, we cannot rule out that there has been the one or other change or shift at least in some areas. This would have to be inquired by future research .

In the following, we formulate hypotheses (twenty hypotheses) for further research on democracy and quality of democracy in global comparison and want to propose these as input for the ongoing discussion:

-

1.

Hypothesis 01/Systematic and comprehensive democracy measurement in global comparison already is possible: We are in a position that we already can carry out and perform in a systematic and comprehensive format an empirical democracy measurement in global comparison . This endeavor may be based on existing, even publicly available data and indicators. New in that respect is also that this endeavor can be conducted truly globally, addressing all countries (democracies , semi-democracies and non-democracies likewise). This global perspective is so important for trying to understand democracy development of quality of democracy , which again appears to be necessary for recognizing democracy comprehensively. There is more data and is more indicator information out there, then is often being realized. This richness in data and indicators allows and encourages creative designs and conceptualizations of democracy and quality of democracy , into which existing data and indicators may be fed into or be “in-puted.” Still, the quality of data is not the same for all indicators. In some areas, data quality and data availability are troublesome. For example, income equality (Gini index or Gini coefficient ) is much less documented than GDP per capita (in its various forms). Comparative research on income equality (or income inequality ), in a global format, is being seriously challenged because of the many data missings for the various Gini indices in the usual data sources and references. Why is it that data documentation for income equality is unfavorably incomplete when being compared with GDP per capita ?Footnote 14 Can GDP even be sufficiently represented, when income distributions are ignored? It appears that data-collecting or data-publishing institutions (at least in some cases) do not place the same emphasis on all indicators (relevant for all dimensions or subdimensions of quality of democracy ). At least this is a possible impression from the outside, when the behavior of institutions (international institutions) is being observed externally, without looking into these institutions (Should this be the case, so why is it?). This non-symmetric quality of different data and indicators has the potential of “bottlenecking” further progress in democracy research , because democracy measurement is not possible to the same extent in all the different dimensions and subdimensions of democracy and quality of democracy .

-

2.

Hypothesis 02/Multidimensional indexation or index-building of democracy as one practical aspect of democracy measurement : Democracy measurement , in principle, can take different forms. Indexations represent one option (viable option). A practical result of democracy measurement may coincide with engaging in a comparative multidimensional index-building for democracy. By this the process of democracy measurement produces as output a scoring and plotting of democracies in reference to a designed structure of dimensions and subdimensions. This index-building for democracy can also set democracies in contrast to semi-democracies and non-democracies . Important here appears to be the aspect that the designing of these indices is multidimensional, allowing and inviting differentiated options for analysis.

-

3.

Hypothesis 03/Parallel codesign (co-development ) of theory of democracy and measurement of democracy : Our understanding of democracy would benefit particularly from a scenario, where (1) theory development or conceptualizations of democracy are conducted and performed in parallel to (2) a further democracy measurement , mutually interlinked and cross-connected, in various conceptual designs. Democracy measurement informs theory of democracy , and theory of democracy structures democracy measurement . Conceptualizing and measuring democracy and quality of democracy are to be seen as parallel processes. This would considerably support learning in theories about democracy. There is a certain impression that democracy theory and democracy measurement still are not sufficiently interlinked and that a gap between theory and measurement continues to prevail.Footnote 15 One thinker about democracy, who seriously engaged himself in cross-connecting theory and practice of democracy, was Guillermo O’Donnell (2004). In this respect, another example are Beetham (1994), Beetham et al. (2002), IDEA (2008).

-

4.

Hypothesis 04/The effects of a specific comparative design on interpretations of democracy and quality of democracy (for example, Latin America in comparison with Asia versus comparisons within Asia ): One standard procedure for comparing democracy (quality of democracy ) is to perform such a comparison country-based, which means to set in contrast democracies (semi-democracies , non-democracies ) of different countries. The specific comparative design must decide, what the specific country selection should be (few countries, several countries or the “whole” world ). The dilemma now is that in dependence of the concrete country selection, somewhat opposite results may be “produced” or may appear to be evident. We want to refer to two examples within context of our work and the applied empirical macromodel. When Latin America and Asia (as aggregated regions) are being compared with each other (for the years 2002–2016), then Latin America is leading in a majority of dimensions and indicators, for example political freedom , gender equality , redesigned Human Development Index , non-political sustainable development , “Comprehensive sustainable development” , life expectancy , tertiary education , GDP per capita and lower CO2 emissions per capita. However, China , as a single Asian country, is dramatically catching up, for example having reached in GDP per capita (in 2016) almost the levels of Latin America and having surpassed Brazil by that year. Latin America , therefore, could serve as an example, where political freedom and non-political sustainable development of society and economy co-evolve symmetrically and within a positive feedback loop and helix (they correlate positively with each other). We would have here a narrative of democracy, where political freedom associates closely with development and sustainable development . When we compare India and China within Asia , results of this comparison are far more ambiguous. India is leading with regard to political freedom ; however, China is leading in non-political sustainable development of society and the economy . With considerably less political freedom , China achieved a higher level of non-political sustainable development . India , on the contrary (and when compared with China ), could not transform its political freedom into a higher level of non-political sustainable development . So here we are facing a much more mixed narrative of democracy, meaning that more political freedom does not translate automatically into more development and sustainable development of society and economy . Which of these two comparisons can claim a higher extent of representativeness for global trends, the comparison of Latin America with Asia or within Asia the comparison of India and China ? Latin America comprises more countries, but China and India clearly outnumber in terms of population the whole of Latin America (China and India aggregate a higher share of world population). These two examples of comparison illustrate, how and why the specific selection of countries for a specific comparative design can actually impact the concrete results of a comparison. Paradoxically formulated: Can a comparison “bias” a representative statement? It is difficult to control , on the “meta-level,” against possible non-representative effects because of case selection. The further dilemma is that we might not be aware of being actually trapped in a non-representative analytical perception. The challenge now is, how to derive from a specific and concrete comparison more general conclusions (propositions) that also are representative? How can we see the “general” picture, based on cases? This makes clear and emphasizes, why the interest in analyzing “global trends” in democracy, democracy development and quality of democracy actually requires a “broadly designed” framework of comparison. But of course, it is more than trivial (and not that ex-ante obvious), how the “whole” world could be captured within one model. Here, again, is a contest between different possible conceptualizations at work and even necessary.

-

5.

Hypothesis 05/ Economic freedom increases faster than political freedom : Within context of our empirical macromodel, there are higher levels of economic than political freedom in the world . Economic freedom is more widespread, whereas political freedom appears to be more constrained, when referred to as global phenomena. Economic freedom not necessarily requires also political freedom , so there can be economic freedom without political freedom (or a coexistence of higher levels of economic and lower levels of political freedom ). For example, Russia and China express lower political freedom , but achieved an economic freedom higher than in India and Brazil . As whole world regions, Latin America scores higher on political freedom than Asia . But in terms of economic freedom , Latin America lies already below of Asia (since 2016). In addition, when we talk about global trends, economic freedom also increased faster than political freedom (while political freedom currently stagnates at the global level). So there has been more progress in the world in economic freedom than in political freedom . Political freedom increased only modestly. In a worst-case scenario, the assertion would be that of a global “stagnation” of political freedom (if not even of a modest current decline in political freedom ).

-

6.

Hypothesis 06/For the procedure of freedom measurement by Freedom House there is the challenge, how to measure and to demonstrate increases in high-level political freedom : Freedom House calculates and publishes its freedom ratings on an annual basis, scores for previous years are not changed and adjusted in retrospect (at least not in a substantive way). The spectrum of possible scores remained also constant, at least in the recent years (Freedom House 2013b, 2018). Methodic considerations or implications of this are that when a country (democracy) receives top scores at one time, then the freedom scores of that country cannot increase in the following years anymore, even when there would have been real gains in political freedom . This creates a so-called ceiling effect or cap for measurement and the expression of political freedom in scores. For example, the Nordic countries scored top on political freedom during the whole period of 2002–2016: we cannot effectively distinguish there anymore, whether there has been no more progress in political freedom in the Nordic countries , or whether we observe here a “ceiling effect” as consequence of a certain methodic procedure being applied. The overall methodic consequence of this may be that the freedom rating of Freedom House is good in capturing and indicating, whether basic standards have been achieved in political rights and civil liberties, necessary for an electoral democracy and essential to a liberal democracy, but that as problem remains, how to trace improvements in the higher levels (high-level spectrum) of political freedom .Footnote 16 This could mean that there exists currently a problem of measurement of political freedom in democracies of a high or higher quality (see Fig. 1.4 in Sect. 1.2). But also in conceptual (and philosophical) terms, we want to refer to the argumentation that we are challenged by the problem, not to understand or comprehend political freedom sufficiently, when (if) political freedom exceeds certain basic standards. For the twenty-first century, this may indicate a need for rethinking and reinventing political freedom , calling for a continued discourse exactly on political freedom .Footnote 17

-

7.

Hypothesis 07/Countries are more similar to each other with respect to economic freedom , but more dissimilar with respect to political freedom : Concerning economic freedom , there is less variation in the world , concerning political freedom there is greater variation (and deviation). With regard to economic freedom (which also increases faster than political freedom ), the different countries are more similar to each other, whereas with regard to political freedom the countries are less similar. In global terms, the average level of economic freedom is also considerably higher than the average for political freedom . This is particularly the case in the non-OECD countries (representing a majority of the world population), but not so for the OECD countries (compare Figs. 5.4 and 5.6 in Chapter 5 with Figs. 3.1 and 3.2 in Chapter 3). In the non-OECD countries, not political freedom , but economic freedom constitutes the model and standard (and ideology), to which countries convert to (by tendency). There we experience empirically several examples of combinations of economic freedom with lower levels of political freedom (in semi-democracies and non-democracies ), which in other circumstances and theoretical contexts could have been regarded to pose and represent a “contradiction.” This “conversion” to (more) economic freedom expresses a conversion to a practical standard in the economy , how to carry out and how to engage in economic affairs. One may also want to assert that the ideology of a free economy increasingly establishes a position of hegemony in the contemporary world . Democracy and political freedom , on the other hand, have not been equally successful in being implemented as a (politically) corresponding standard. From a philosophical viewpoint of conceptualization , also another argument appears to be possible here: greater similarity in economic freedom could also be interpreted as an indication that there is more of a consensus in economic thinking and acting about the relevant economic models to be applied. Greater dissimilarity in political freedom may mean that there is less of a consensus in political assessment on “good politics” (or even “good governance ”). In that respect, political thinking would be more (is more) fragmented, and more controversial, caught in polarization between conflicting paradigms.

-

8.

Hypothesis 08/ Gender equality increases faster than income equality : As a global trend, gender equality increases. This apparently is the case for the world in general, but also for OECD and non-OECD countries more specifically. These increases in gender equality are being sharply contrasted by the developments in income equality . For the whole world , a scenario of stagnation in income equality must be stated, in context of the OECD countries (USA, EU15 , but also the Nordic countries ) income equality even decreases and decreased.Footnote 18 So there may be a troublesome tendency be spotted (and asserted), where higher levels of GDP per capita scores actually associate with a downward tendency in income equality . Should income equality fall below crucial and sensitive thresholds, then wealth and GDP per capita does not circulate sufficiently anymore in society and economy , and aggregated GDP per capita values and benchmarks do not translate into real incomes for a larger number of average people in the population. There are non-OECD countries, for example India , who are expressing higher levels of income equality than some of the OECD countries, such as the USA. With regard to gender equality , the countries are more similar to each other, with regard to income equality , countries are more dissimilar. This is the case for OECD as well as non-OECD countries, but more so even for the non-OECD countries (compare Figs. 3.3 and 3.4 in Chapter 3 with Figs. 4.4 and 4.5 in Chapter 4). Gender equality and income equality can be characterized by opposite trends. Increases in gender equality are confronted by a stagnation or even decline in income equality . To a certain extent, this is paradoxical, because inequalities in gender do also manifest themselves partially in gender-based income inequalities. This raises the challenging (and provoking) question, to which extent gender equality as an issue and theme, but also as a reference point for political competition in the political arena (of elections and voting), is gradually replacing income equality (as a theme) or is pushing income equality more to the sidelines of attention. In contemporary context, there may be more awareness and sensitivity for gender equality than for income equality . Data quality for income equality in global comparison (for example, on the basis of the Gini index or Gini coefficient ) is furthermore poorer when contrasted with other indicators (also on gender equality ). This creates a serious demand and clearly more need for more and better data on income equality . National and international institutions are being equally challenged here in their data collecting and reporting procedures. It is problematic, when GDP per capita can count on a more systematic documentation than income distribution. So why is there this “fog,” when we want to have more transparency on data on income equality ? There should be more emphasis to establish data (indicators) on income equality (also wealth equality ), also in context of Gini index measures, as a general standard in all regular data sources that refer to countries (see World Bank 2018; World Inequality Database 2018a, b).

-

9.

Hypotheses 09/There is a need for designing a “Median” GDP per capita benchmark indicator: Stagnating or decreasing levels of income equality call for more data information in this area and respective field. In context of national accounts, GDP per capita represents an indicator based on aggregation and is to a considerable extent not sensitive (enough) for distributions of income and wealth within a country. There should be systematic contemplation, how a “Median” GDP per capita could be designed and implemented, reflecting the “real” average (median) income (or wealth ) of a person within a specified and specific society . The comparison of countries in reference to a “Median” GDP per capita would probably reveal interesting results.

-

10.

Hypotheses 10/ Freedom progresses in the world faster than equality : When the OECD countries are being compared with the whole world (OECD and non-OECD countries, but with a focus on non-OECD ), then the OECD is leading in the dimensions of freedom and equality . However, this lead is crucially unsymmetric. The lead is the greatest in the subdimensions of political freedom and economic freedom , but more marginal in gender equality and income equality (see Fig. 5.7 in Chapter 5 and Fig. 7.5 in Sect. 7.1). World and OECD increased their growth rates, with the greatest growth rates for gender equality and economic freedom , and the weakest growth rates (or even declines) for income equality and political freedom (see Figs. 5.8 and 5.9 in Chapter 5). When we are focusing now on the “levels,” this allows us to formulate the proposition that progress in OECD countries (when compared with the whole world or the non-OECD countries more specifically) benefitted primarily freedom , whereas improvements in equality were more marginal (with the only exception of gender equality ). Within the dimension of freedom , the more recent progress focused even more so on economic freedom . It is “more freedom ,” which makes the difference between the OECD and non-OECD worlds, but not necessarily “more equality .” There has been more progress in gender equality , but considerably less progress or even a decline in income equality . Progress in the OECD countries was to the advantage of freedom , but less so to the advantage of equality , if at all. Gender equality has risen, but not income equality . This provokes the critical or cynical question, whether equality was “sacrificed” for gains in freedom ? Advances during the course of economic development boosted freedom (and economic freedom ) in the OECD countries, however, not to the same extent equality . Is this the one implication of having established the hegemonic model of a “free economy ” as dominant economic paradigm in the advanced economies of the OECD ? Indeed, it puzzles, how marginal increases in equality are (with the exception of gender equality ), when we consider and factor in all the efforts of progress and development , which the OECD countries accumulated, and then compare the OECD countries with non-OECD countries. But what is the meaning of progress, should this only lead to more freedom , and not also to more equality ? Stagnating or even declining income equality poses a serious challenge and problem for democracy and quality of democracy in the advanced OECD countries. Could this even have the potential of an eroding political freedom (and a feeding of radical populism) in a mid-term or long-term perspective? Probably we are still not fully aware, what the whole impact of this possibly is or may be. It seems clear and evident that there is a greater need for more research on equality , also income equality particularly (in that respect, for example, see Piketty 2015; Wilkinson and Pickett 2010).

-

11.

Hypothesis 11/There is a tendency that in world context and averaged as world means the non-political indicators grow (grew) faster and express a more dynamic profile of progress, progressing and advancement than the political indicators. For example: the redesigned Human Development Index as well as non-political sustainable development outperform the “Comprehensive sustainable development” (which includes political freedom ). Also economic freedom progresses faster than political freedom . Furthermore, the more narrowly defined (in terms of used and integrated indicators) redesigned Human Development Index expanded faster than the more broadly defined non-political sustainable development . This creates puzzles and challenges. One proposition could assert that more modest improvements in the political sphere are being outpaced by more dynamic improvements in the non-political spheres. Therefore, are society and economy of a greater importance than politics? What does this tell us about democracy and the relevance of democracy (for growth )? Should democracy place a greater concern on non-political issues and characteristics? Different interpretations and implications are feasible or could be applied. In the following, we want to refer to a few possible conclusions: (1) In the case of some political indicators, such as political freedom , we may still face a conceptual problem of how to measure these adequately. What could result are minimum or minimalist definitions, for example for political freedom , with the consequence that only a passing of certain thresholds becomes evident and can be documented, whereas the measuring of higher levels of maturity still represents a real challenge. (2) Minimalist definitions of democracy, focusing and concentrating on fewer and limited political aspects and political characteristic, perhaps communicate and deliver the impression of a world wide tendency of a stagnation or only modest improvement for the endeavor of democracy. Broader conceptualizations of democracy that emphasize the importance of sustainable development for the quality of a democracy and that refer therefore to developments and improvements of society and economy (and in society and in economy ) reveal (by tendency) perhaps a different picture: when such broader conceptualizations are being translated into attempts of empirical measurement (by this including also non-political indicators), then we may see in global context a more progressive development of society and economy (also of knowledge society and knowledge economy ), and to a certain extent also of democracy or at least of the opportunities and prospects for democracy (including the concept of knowledge democracy ). In practical terms, what this can mean is (for example): should medium-high or very-high scores of political freedom stagnate, then democracies still can focus on improving their “non-political ” sustainable development in society (and in economy ). To raise for discussion, a radical proposition or at least a challenging question: Is there a certain plausibility to assert that also in theoretical terms the broader conceptualization of democracy and the quality of democracy is more dynamic (by referring also to development , also to non-political development ) than minimalist conceptual approaches toward democracy and the quality of democracy (that only look on political freedom in a narrow sense)?

-

12.