Abstract

The analytical research question of this chapter is threefold: (1) To develop (and to prototype) a conceptual framework of analysis for a global comparison of quality of democracy. This framework also references to the concept of the “Quadruple Helix innovation systems” (created by Carayannis and Campbell and first published in 2009). (2) The same conceptual framework is being used and tested for comparing and measuring empirically quality of democracy in the different OECD and European Union (EU27) member countries. (3) Finally (and based on the international comparison), different propositions and recommendations for an improvement of quality of democracy reform in Austria are being developed and suggested. By this, Austrian democracy qualifies as a case study for democracy enhancement. In theoretical and conceptual terms, we refer to a Quadruple-dimensional structure, also a Quadruple Helix structure (a “Model of Quadruple Helix Structures”) of the four basic (conceptual) dimensions of freedom, equality, control, and sustainable development for explaining and comparing democracy and quality of democracy. Put in summary, we may conclude for the United States: the comparative strength of quality of democracy in the United States focuses on the dimension of freedom. The comparative weakness of the quality of democracy in the United States lies in the dimension of equality, most importantly income equality. Quadruple Helix refers here to at least two crucial perspectives: (1) the unfolding of an innovative knowledge economy also requires (at least in a longer perspective) the unfolding of a knowledge democracy and (2) knowledge and innovation are being defined as key for sustainable development and for the further evolution of quality of democracy. How to innovate (and reinvent) knowledge democracy? There is a potential that democracy discourses and innovation discourses advance in a next-step and two-way mutual cross-reference. The architectures of Quadruple Helix (and Quintuple Helix) innovation systems demand and require the formation of a democracy, implicating that quality of democracy provides for a support and encouragement of innovation and innovation systems, so that quality of democracy and progress of innovation mutually “Cross Helix” in a connecting and amplifying mode and manner. This relates research on quality of democracy to research on innovation (innovation systems) and the knowledge economy. “Cyber-democracy” receives here a new and important meaning.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Austria

- Basic Quadruple-dimensional structure of quality of democracy

- Cyber-democracy

- Democracy

- Democracy improvement and reform

- Equality

- Freedom

- Interdisciplinary

- International comparison of OECD and European Union member countries

- Knowledge democracy

- Quadruple and Quintuple Helix

- Quadruple Helix innovation systems

- Quality of democracy

- Sustainable development

- Transdisciplinary

- United States

Introduction: Research Design and Research Question for the Comparative Analysis

This chapter focuses on analyzing quality of democracy in a comparative approach. Even though comparisons are not the only possible or legitimate method of research, our contribution is based on the opinion that comparisons provide crucial analytical perspectives and learning opportunities. Therefore, our analysis is being guided and governed by the following proposition: national political systems (political systems) are comprehensively understood only by using an international comparative approach. International comparisons (of country-based systems) are common (see the status of comparative politics, e.g., in Sodaro 2004). Comparisons do not have to be based necessarily on national systems alone but can also be carried out using “within” comparisons inside (or beyond) subunits or regional subnational systems, for instance, the individual provinces in the case of Austria (Campbell 2007, p. 382).

The pivotal analytical research question of this chapter is threefold:

-

1.

To develop (to “prototype”) a conceptual framework of analysis for a global comparison of quality of democracy. This framework will also reference to the concept of the “Quadruple Helix innovation systems” (Carayannis and Campbell 2009, 2014, 2015). Quadruple Helix and Quadruple Helix structures represent here an interdisciplinary (and transdisciplinary) linkage that connects research in quality of democracy with innovation concepts (see also Bast et al. 2015; furthermore, see also the website of “Arts, Research, Innovation and Society,” ARIS: http://www.dieangewandte.at/aris). This interdisciplinary perspective should furthermore emphasize the overall importance of knowledge (and of knowledge and innovation) for society, economy, and democracy.

-

2.

This same conceptual framework will be used and will be tested for comparing and measuring quality of democracy in the different OECD and European Union (EU27) countries. First propositions are being formulated about democracy in the United States but clearly need further follow-up inquiry in a later phase and discourse. This comparison is more exploratory in nature and character and wants to provide further evidence about the usefulness of the developed framework. This framework should inspire and inform future research on quality of democracy but also future research in reference to knowledge and innovation systems (see also Campbell 2012; Campbell et al. 2013, 2015; Campbell and Carayannis 2014).

-

3.

Finally (and based on the international comparison), different propositions and recommendations for an improvement of quality of democracy reform in Austria are being developed and suggested: by this, Austrian democracy qualifies as a case study for democracy enhancement (see also Campbell 2015a, b; Campbell and Carayannis 2014).

In our analysis presented here, quality of democracy should be compared mutually between all member countries to the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) and all the member countries to the European Union (EU15, EU27, without Croatia), thus leading to a country-based comparison of democratic quality (most, however not all member countries of the EU are also member countries to the OECD). Supranational aggregations (like of the whole European Union at the EU level of institutions) or transnational aggregations (global level) shall not be dealt with. The OECD consists primarily of the systems of Western Europe (EU as well as non-EU), North America (United States and Canada), Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. Outside these regions, Israel, Mexico, and Chile are part of the OECD, which highlights the global expansion and reach of OECD. The OECD countries can be majorly determined over the following two features: economically as “advanced economies” (IMF 2011, p. 150) and politically the majority of the OECD countries are determined as “established democracies” or as “Western democracies.” Furthermore, we may also discuss, how relevant the concepts of “advanced societies” and “advanced democracies” are (Carayannis and Campbell 2011, p. 367; also 2012). However, in this context it appears more crucial that the OECD countries (again by the majority) can be seen as an empirical manifestation of liberal democracy, as known in the beginning of the twenty-first century. Ludger Helms (2007 p. 18) pointed out: “For a system to be identified as a liberal democracy, or simply as liberal-democratic, liberal as well as democratic elements have to be realized in adequate volumes” (quotes from original sources in German were translated into English by the authors of this analysis). Just as decisive is Helms’ (2007 p. 20) statement: “The political systems of Western Europe, North America and Japan examined in this study can be distinguished – despite all the differences – as liberal democracies.” Since the OECD countries are majorly represented by advanced democracies and advanced economies, the OECD countries are very suitable as a peer group for the comparisons of different OECD countries, for example, the United States with other OECD countries, in order to carry out a “fair” comparison. For a comparison of the quality of democracy of the United States with other countries (democracies), the “comparative benchmark” must be of the highest possible standard, in order to submit propositions that test the actual quality of a concrete democracy. Concerning quality of democracy, what can the United States learn from other democracies? This same question applies also to all the other democracies.

This emphasis of the OECD comparative assessment of quality of democracy will not be based on a time series pattern; instead (see section “The International Comparison (Part One): Focus on the Year 2010”), it will focus on an indicator-specific system using empirical information available from a more recent year (mostly 2010, referring to data publicly accessible as of early 2012). Since our analysis is more explorative in character (wanting to test the design of a developed comparative framework), the year 2010 qualifies as sufficiently recent. However, in section “The International Comparison (Part Two): Comparison of the Years 2011–2012 and 2014–2015,” also a trend comparison of the years 2011–2012 and 2014–2015 is being presented additionally, with a discussion of the results. The mentioned reference year of 2010 or 2012 explains why we did not include Croatia into our analysis. Croatia joined the European Union as late as 2013, creating by this the EU28. With the planned retreat of the United Kingdom (UK) from the EU, as a consequence of the British “Brexit” referendum in 2016, the EU then would transform back into an EU27. The UK withdrawal from EU is expected to take place during the course of the year 2019. To support our analysis, a broad spectrum of indicators will be considered for this purpose of comparative inquiry, which appears to be necessary in order to conclude different (underlying) theories and models about quality of democracy. Follow-up studies will certainly be conceivable to integrate this empirically comparative snapshot of the quality of democracy. As of August 2017, the OECD has 35 member countries (http://www.oecd.org/about/membersandpartners/). These OECD member countries define the primary reference framework for the international comparison in this analysis. Since not every member state of the current EU27 is a member of the OECD, the decision to include the non-OECD countries of the EU27 countries was made for the country comparison, which therefore results in an expansion of the group of countries to “OECD plus EU27.” These additional countries are Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Romania, and Cyprus. In total, our presented country sample for the comparison of quality of democracy consists of about 40 countries.

There is naturally not only a single democracy theory (theory about quality of democracy), but the field of democratic theories is rather pluralistic and heterogeneous. Various theories and models coexist about democracies (Cunningham 2002; Held 2006; Munck 2014; Schmidt 2010). Metaphorically, based on these (partly contradictory) different theories, democracy theory could also be constructed as a metatheory. Theoretically, democracy can be understood as multi-paradigmatic, meaning that there is not only one (dominant) paradigm for democracy. Therefore, we have to state pluralism, competition, coexistence and co-development of different theories about democracy. Our analysis is based on the additional assumption (which does not have to be shared necessarily) that between democracy theory on the one hand and democracy measurement on the other hand, important (also conceptual) cross-references (and linkages) take place. Within this logic, a further development or improvement of the democracy theory demands a systematic attempt of democracy measurement, regardless of how incomplete or problematic an empirical assessment of democracy is. Just like there is no “perfect” democracy measurement, there is also no “perfect” democracy theory (see, e.g., Campbell and Barth 2009; Geissel et al. 2016; Helms 2016; Lauth et al. 2000; Lauth 2004, 2010, 2011, 2016; Munck 2009, 2014; Schmidt 2010, pp. 370–398). Theories about the quality of democracy are partly already further developed, than it is often (in popular research) being assumed. One of the most important theory models about the quality of democracy that permits an empirical operationalization comes from Guillermo O’Donnell (2004a, b). The field of the quality of democracy is no longer a vague one, especially not for OECD countries.

The further structure of this chapter is divided into the following sections: in section “Conceptualizing Democracy and the Quality of Democracy: Freedom, Equality, Control and Sustainable Development (Model of Quadruple Helix Structures),” different conceptualizations of democracy and of quality of democracy are being presented, followed (in section “The Quality of Democracy in Comparative Perspective: A Comparative Empirical View of the OECD Countries (and EU27 Member Countries) Relating to the Dimensions of Freedom, Equality, Control, and Sustainable Development”) by the concrete empirical comparison of quality of democracy in the OECD countries and the member countries to the European Union. In the conclusion (section “Conclusion: Quality of Democracy in Quadruple Helix Structures”), we attempt to assess quality of democracy in the United States, based on the formulation of first propositions, and furthermore engage in propositions and recommendations for a further quality of democracy reform in Austria . In the epilogue (section “Epilogue on Cyber-Democracy”), we develop and discuss further moving thoughts on cyber-democracy. Furthermore, the “Quadruple Helix” is being emphasized as an interdisciplinary and a transdisciplinary approach for bringing democracy discourses and innovation discourses closer together.

Conceptualizing Democracy and the Quality of Democracy: Freedom, Equality, Control, and Sustainable Development (Model of Quadruple Helix Structures)

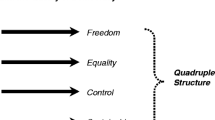

How can democracy and the quality of democracy be conceptualized? Such a (theoretically justified) conceptualization is necessary in order for democracy and the quality of democracy to be subjected to a democracy measurement, whereby democracy measurement, in this case, can be examined along the lines of the definition of democracy (thus democracy measurement to be utilized to improve the democracy theory). Hans-Joachim Lauth (2004, pp. 32–101) suggests in this context a “three-dimensional concept of democracy,” which is composed of the following (conceptual) dimensions: equality, freedom, and control (see Figs. 1 and 2). These dimensions we want to interpret as “basic dimensions” of democracy and of the quality of democracy. Lauth (2004, p. 96) underlines that these dimensions are “sufficient” to obtain a definition of democracy. The term “dimension” offers a conceptual elegance that can be applied “trans-theoretically,” meaning that different theories of democracy may be put in relation and may be mapped comparatively in reference to those dimensions. Metaphorically formulated, dimensions behave like “building blocks” for theories and the continuing development of theory. In the following analysis (see later), we furthermore propose to introduce “sustainable development” as a further basic dimension for democracy and quality of democracy. To do this was (first) explicitly suggested by Campbell (2012, pp. 296, 301–302; see also Campbell 2017).

Empirically, it should also be added that the traditional public perception of Western Europe indicates that individuals with a more-left political orientation prefer equality and individuals with a more-right (conservative) political orientation have preferences for freedom (Harding et al. 1986, p. 87). The European left/right axis would translate itself well for the North American contexts by using a liberal/conservative axis (with left = liberal and right = conservative).

With regard to democracy and the quality of democracy, we are confronted with the following point-of-departure question: whether (1) democracy as a key feature or criterion exclusively refers or should refer to the political system or whether (2) democracy should also include social (societal), economic, as well as ecological contexts of the political system. This produces implications on the selection of indicators to be used for democracy measurement. How “limited” or “broadly” focused should be the definition of democracy? This is also reflected in the minimalistic versus maximalist democracy theory debate (see, e.g., Sodaro 2004, pp. 168, 180, and 182). In this regard, various theoretical positions elaborate on this concept. Perhaps, it is (was) from an orthodox point of view of theory to limit democracy to the political system (Munck 2009, pp. 126–127). More recent approaches are more sensitive for the contexts of the political system, however, still must establish themselves in the political mainstream debates (see, e.g., Stoiber 2011). Nevertheless, explicit theoretical examples are emerging for the purpose of incorporation into the democracy models the social (societal), economic, and ecological contexts. The theoretical model of the “Democracy Ranking” is an initiative that represents such an explicit example (Campbell 2008; Campbell et al. 2013). The Democracy Ranking is an international civil society initiative that measures regularly quality of democracy in a global approach and comparison (for more detailed information, visit the website of the Democracy Ranking at: http://democracyranking.org/).

Over time, democracy theories are becoming more complex and demanding in nature, regardless, whether the understanding of democracy refers only to the political system or includes also the contexts of the political system. This also reflects on the establishment of democracy models or models of politics (see here, for an overview: Campbell 2013; Geissel et al. 2016; Giebler and Merkel 2016; Helms 2016; Lauth 2016; Morlino and Quaranta 2016; Munck 2014; Schedler 2006; Schmitter 2004). The most simple democracy model is that of the “electoral democracy” (Helms 2007, p. 19), also known as “voting democracy” (“Wahldemokratie”; Campbell and Barth 2009, p. 212). An electoral democracy focuses on the process of elections, highlights the political rights, and refers to providing minimum standards and rights, however, enough to be classified as a democracy. Freedom House (2011a) defines electoral democracy by using the following criteria: “A competitive, multiparty political system,” “Universal adult suffrage for all citizens,” “Regularly contested elections,” and “Significant public access of major political parties to the electorate through the media and through generally open political campaigning.” The next, qualitatively better level of democracy is the so-called liberal democracy. A liberal democracy is characterized by political rights and more importantly also by civil liberties as well as complex and sophisticated forms of institutionalization. The liberal democracy does not only want to fulfill minimum standards (thresholds) but aims on ascending to the quality and standards of a developed, hence, an advanced democracy. Every liberal democracy is also an electoral democracy, but not every electoral democracy is automatically a liberal democracy (on elections see also Rosenberger and Seeber 2008). In this regard, Freedom House (2011a) states: “Freedom House’s term ‘electoral democracy’ differs from ‘liberal democracy’ in that the latter also implies the presence of a substantial array of civil liberties. In the survey, all the ‘Free’ countries qualify as both electoral and liberal democracies. By contrast, some ‘Partly Free’ countries qualify as electoral, but not liberal, democracies.” Asserting different (perhaps ideal-typical) conceptual stages of development for a further quality increasing and progressing of democracy, we may put up for discussion the following stages: electoral democracy, liberal democracy, and advanced (liberal) democracy with a high quality of democracy.

In Polyarchy, Robert A. Dahl (1971 pp. 2–9) comes to the conclusion that mostly two dimensions suffice in order to be able to describe the functions of democratic regimes: (1) contestation (“public contestation,” “political competition”) as well as (2) participation (“participation,” “inclusiveness,” “right to participate in elections and office”). In Figs. 3 and 4, we propose to interpret these two dimensions, introduced by Dahl, as “secondary dimensions” for describing democracy and democracy quality for the objective of measuring democracy. Also relevant are Anthony Downs’ eight criteria in An Economic Theory of Democracy (1957, pp. 23–24), defining a “democratic government,” but it could be argued that those are affiliated closer with an electoral democracy. In the beginning of the twenty-first century is the conceptual understanding of democracy and the quality of democracy already more differentiated, it can be said that crucial conceptual further developments are in progress. Larry Diamond and Leonardo Morlino (2004, pp. 22–28) have come up with an “eight dimensions of democratic quality” proposal. These include (1) rule of law, (2) participation, (3) competition, (4) vertical accountability, (5) horizontal accountability, (6) freedom, (7) equality, and (8) responsiveness. Diamond and Morlino (2004, p. 22) further state: “The multidimensional nature of our framework, and of the growing number of democracy assessments that are being conducted, implies a pluralist notion of democratic quality.” These eight dimensions distinguish themselves conceptually with regard to procedure, content, as well as results as the basis (conceptual quality basis) to be used in differentiating the quality of democracy (see Diamond and Morlino 2004, pp. 21–22; 2005; see also Campbell and Barth 2009, pp. 212–213). The “eight dimensions” of Diamond and Morlino may be interpreted as “secondary dimensions” of democracy and the quality of democracy for the purpose of democracy measurement (see again Figs. 3 and 4).

“Earlier debates were strongly influenced by a dichotomous understanding that democracies stood in contrast to non-democracies” (Campbell and Barth 2009, p. 210). However, with the quantitative expansion and spreading of democratic regimes, it is more important to differentiate between the qualities of different democracies. According to Freedom House (2011b), in the year 1980, no less than 42.5% of the world population lived in “not free” political contexts. By 2010, this share dropped to 35.4%. Democracies themselves are subject to further development, which is a continuous process and does not finish upon its establishment. Democracies have to find answers and solutions to new challenges and possible problems. Democracies are in constant need to find and reinvent themselves. Observed over time, different scenarios could take place and could keep a democracy quality going on constantly; democracy quality could erode but also improve. A betterment of the quality of democracy should be the ultimate aim of a democracy. Earlier ideas about an electoral democracy are becoming outdated and will not suffice in today’s era.

Guillermo O’Donnell (2004a) developed a broad theoretical understanding of democracy and the quality of democracy. In his theoretical approach, quality of democracy develops itself further through an interaction between human development and human rights: “True, in its origin the concept of human development focused mostly on the social and economic context, while the concept of human rights focused mostly on the legal system and on the prevention and redress of state violence” (O’Donnell 2004a, p. 12). The human rights differentiate themselves in civil rights, political rights, and social rights, in which O’Donnell (2004a, p. 47) assumes and adopts the classification of T. H. Marshall (1964). Human development prompts “…what may be, at least, a minimum set of conditions, or capabilities, that enable human beings to function in ways appropriate to their condition as such beings” (O’Donnell 2004a, p. 12), therefore in accordance with human dignity and, moreover, the possibility of participating realistically in political processes within a democracy. O’Donnell also refers directly to the Human Development Reports with the Human Development Index (HDI) that are being released and published annually by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) (for a comprehensive website address for all Human Development Reports that is publicly accessible for free downloads, see http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2011/). Explicitly, Guillermo O’Donnell (2004a, pp. 11–12) points out: “The concept of human development that has been proposed and widely diffused by UNDP’s Reports and the work of Amartya Sen was a reversal of prevailing views about development. … The concept asks how every individual is doing in relation to the achievement of ‘the most elementary capabilities, such as living a long and healthy life, being knowledgeable, and enjoying a decent standard of living’” (O’Donnell 2004a, pp. 11–12; UNDP 2000, p. 20). If the implementation of O’Donnell is reflected upon the initial questions asked in this contribution for the conceptualization of democracy and the quality of democracy, it can be interpreted but also convincingly argued that “sustainable development” can be suggested as an additional dimension (“basic dimension”) for democracy, which would be important for the quality of democracy in a global perspective (see again Campbell 2012, pp. 296, 301–302, and compare with Campbell 2017). For a systematic attempt of empirical assessment on possible linkages between democracy and development, see Przeworski et al. (2003). As a result of the distinction between dimensions (basic dimensions) for democracy and the quality of democracy, the following proposition is put up for debate: in addition to the dimensions of freedom, equality, and control as being suggested by Lauth (2004, pp. 32–101), the dimension of sustainable development should be introduced as a fourth dimension (see again Fig. 1). Regarding suggestions for defining sustainable development, Verena Winiwarter and Martin Knoll (2007, pp. 306–307) commented: “In the meantime, as described, multiple definitions for sustainability exist. A fundamental distinction within the definition lies in the question whether only the relation of society with nature or if additionally social and economic factors should be considered.”

There are different theories, conceptual approaches, and models for knowledge production and innovation systems. In the Triple Helix model of innovation, Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff (2000, p. 112) developed a conceptual architecture for innovation, where they tie together the three helices of academia (higher education), industry (business), and state (government). This conceptual approach was extended by Carayannis and Campbell (2009, 2012, p. 14) in the so-called Quadruple Helix model of innovation systems by adding as a fourth helix the “media-based and culture-based public,” “civil society,” and “arts, artistic research, and arts-based innovation” (Carayannis and Campbell 2014, pp. 6, 15; 2015, pp. 41–42; Bast et al. 2015). The Quadruple Helix, therefore, is broader than the Triple Helix and contextualizes the Triple Helix, by interpreting Triple Helix as a core model that is being embedded in and by the more comprehensive Quadruple Helix. Furthermore, the next-stage model of the Quintuple Helix model of innovation contextualizes the Quadruple Helix, by bringing in a further new perspective by adding additionally the “natural environment” (natural environments) of society. The Quintuple Helix represents a “five-helix model,” “where the environment or the natural environments represent the fifth helix” (Carayannis and Campbell 2010, p. 61). In trying to emphasize, compare, and contrast the focuses of those different Helix innovation models, we can assert that the Triple Helix concentrates on the knowledge economy, the Quadruple Helix on knowledge society and knowledge democracy, while the Quintuple Helix refers to socioecological transitions and the natural environments (Carayannis et al. 2012, p. 4; see also Carayannis and Campbell 2011). For explaining and comparing democracy and the quality of democracy, we propose a “Quadruple-dimensional structure” of four different “basic dimensions” of democracy that are being called freedom, equality, control, and sustainable development (Fig. 1 offers a visualization on these). Here, we actually may draw a line of comparison between concepts and models in the theorizing on democracy and democracy quality and the theorizing on knowledge production and innovation systems. This also opens up a window of opportunity for an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaching of democracy as well as of knowledge production and innovation. In conceptual terms, the Quadruple-dimensional structure of democracy could also be rearranged (re-architectured) in reference to helices, by this creating a “Model of Quadruple Helix Structures” for democracy and the quality of democracy. The metaphor and visualization in reference to terms of helices emphasize the fluid and dynamic interaction, overlap, and coevolution of the individual dimensions of democracy. As basic dimensions for democracy, we propose (proposed) to identify freedom, equality, control, and sustainable development. Figure 5 introduces a possible visualization from a helix perspective for a theoretical framing of democracy. With respect to further characteristics and trend developments in and of knowledge democracy , see also the conceptual framings and discussions in In’t Veld and Roeland (2010).

The Quadruple Helix structure of the basic dimensions of democracy and the quality of democracy (Source: Authors’ own conceptualization based on Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff (2000, p. 112), Carayannis and Campbell (2012, p. 14), Danilda et al. (2009), Campbell (2008, p. 32), and for the dimension of “control” on Lauth (2004, pp. 32–101))

As already being mentioned, equality is often associated closer with left-wing political positions and freedom with right-wing positions. A measure of performance of political and nonpolitical dimensions in relation to sustainable development has the advantage (especially in the case where sustainable development is understood comprehensively) that this procedure is mostly (often) left/right neutral. Such a measure of performance as a basis of the assessment of democracy and quality of democracy offers an additional reference point (“meta-reference point”) outside of usual ideologically based conflict positions (Campbell 2008, pp. 30–32). It can be argued in a similar manner that the dimension of control mentioned by Lauth (2004, pp. 77–96) positions itself as left-right neutral as well. The definition developed by the “Democracy Ranking” for the quality of democracy is “Quality of Democracy = (freedom & other characteristics of the political system) & (performance on the nonpolitical dimensions).” The definition is interpreted as a further empirical operationalization step and as a practical application for the measurement of democracy and the quality of democracy respectively which is based on the theory about the quality of democracy by Guillermo O’Donnell. However, the conceptual democracy formula of the Democracy Ranking has been developed independently (Campbell and Sükösd 2002).

There exist several global initiatives that commit themselves to a regular empirical democracy measurement. It cannot be convincingly argued that there are no data or indicators for a systematically comparative measurement of democracy (at least in the recent years). Of course there can and should be discussions about the quality of these data and their cross-references to theory of democracy. The works of Freedom House (see, e.g., Gastil 1993) and of the Democracy Ranking shall be elaborated in more detail during the analysis of the quality of democracy in the United States and in Austria. Other initiatives (without claiming entirety) include Vanhanen’s Index of Democracy (Vanhanen 2000) (see http://www.prio.no/CSCW/Datasets/Governance/Vanhanens-index-of-democracy), Polity IV (see http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm), Democracy Index (EIU 2010) (see http://www.eiu.com/public/topical_report.aspx?campaignid=demo2010), and the Democracy Barometer (Bühlmann et al. 2011) (see http://www.democracybarometer.org/). For a comparison of different initiatives, see Pickel and Pickel (2006, pp. 151–277) and Campbell and Barth (2009, pp. 214–218). The Democracy Barometer provides a “concept tree” (“Konzeptbaum”) for the quality of democracy which also consists of the three dimensions of freedom, control, and equality: “The Democracy Barometer assumes that democracy is guaranteed by the three principles of Freedom, Control and Equality.” The original quote in German is “Das Democracy Barometer geht davon aus, dass Demokratie durch die drei Prinzipien Freiheit, Kontrolle und Gleichheit sichergestellt wird” (see http://www.democracybarometer.org/concept_de.html). A strong resemblance with the three (basic) dimensions of democracy by Lauth (2004, pp. 32–101) is evident in which the talk is also about equality, freedom, and control (Fig. 1).

The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) , established in Stockholm, Sweden, dedicated itself to the approach of the Democratic Audit by assessing the quality of democracy (see http://www.idea.int/). IDEA uses its own State of Democracy (SoD) Assessment Framework for this purpose which is built on the following two principles: “popular control over public decision-making and decision-makers” and “equality of respect and voice between citizens in the exercise of that control” (IDEA 2008, p. 23). This framework is understood as a further level of operationalization for the democracy assessment of such concepts developed by David Beetham. Beetham (1994, p. 30, 2004) argues that a “complete democratic audit” has to cover the following areas: “free and fair elections,” “civil and political rights,” “a democratic society,” and “open and accountable government.” Beetham has been successively involved in various democratic audit processes in the United Kingdom (see, e.g., Beetham et al. 2002), and moreover (at least for the further conceptual development) he is also committed with IDEA (see again IDEA 2008). The assessment framework of IDEA for democracy evaluation has been applied to 21 countries since 2000, however excluding Austria, Germany, and Switzerland (for an overview see http://www.idea.int/sod/worldwide/reports.cfm).

Besides those more globally reaching initiatives of a comparative assessment of quality of democracy, other studies prefer focusing on the democracy of a particular country. For example, Austria represents the type of an advanced small-sized country democracy in Europe, also being a member country to the European Union. To summarize the current status of research and studies regarding the quality of democracy in Austria , the mid-1990s provide a useful starting point. The “Die Qualität der österreichischen Demokratie” (Quality of Democracy in Austria, by Campbell et al. 1996) represented the first attempt to analyze the Austrian quality of democracy, at least from an academic (and sciences-based) point of view. The next, once again systematic approach of evaluation of the Austrian quality of democracy took place in the “Demokratiequalität in Österreich” (Quality of Democracy in Austria, by Campbell and Schaller 2002). In the meantime, this book already can be downloaded for free as a whole and complete PDF from the web (visit the following link: http://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/View/?resid=12473). In an exclusive chapter contribution from this volume, an attempt was made to understand or to position the quality of democracy of Austria interactively between basic rights or human rights (“Grundrechten”) on one hand and power-balancing structures (“Macht-ausbalancierenden Strukturen”) on the other (Campbell 2002, p. 19). “Grundrechte” here may be interpreted as human rights as they are being proposed by Guillermo O’Donnell (2004a, pp. 12, 47). In reference to the already mentioned basic dimensions of democracy and the quality of democracy, the power-balancing structures (“Macht-ausbalancierenden Strukturen” or “Macht-ausgleichenden Strukturen”) may be aligned to the dimension of control (see Lauth 2004, pp. 77–96). Later studies have already started preferring a comparative approach (see Beck and Schaller 2003; Fröschl et al. 2008; Barth 2010, 2011; Campbell 2012, 2015a, b) .

The Quality of Democracy in Comparative Perspective: A Comparative Empirical View of the OECD Countries (and EU27 Member Countries) Relating to the Dimensions of Freedom, Equality, Control, and Sustainable Development

The International Comparison (Part One): Focus on the Year 2010

The following session validates the quality of democracy in the OECD (EU27) countries through empirical indicators by providing a comparative approach and analysis in order to create a platform to discuss the propositions for assessing and analyzing quality of democracy (as is being finally attempted in section “Conclusion: Quality of Democracy in Quadruple Helix Structures”). Assessment, even more importantly evaluation, is being used here less to provide factual statements but rather more as a stimulant for discussion and to search for possibilities to improve democracy. Evaluation is therefore meant to provoke democracy learning (“Demokratielernen”). The benchmark for comparison covers all the member states of the OECD, complemented by the remaining member states of the EU27. The chosen time frame is always the last year with available data information (as of early 2012), usually extracted from the year 2010. Partially, in the following Tables 1 and 2, we had to estimate, to which calendar year a specific index year referred to. Only available indicators were used and no new indicators were created. This emphasized and emphasizes to refer to already existing knowledge. Indicators being used are from such institutions (organizations) that have a relatively “impartial” (“nonpartisan”) reputation but also reflect a certain consensual “mainstream” point of view. Possible critical findings weigh even more for this particular reason. That should also underline that the OECD countries have been well documented regarding indicators over a longer period of time (which does not deny the need for new and even better indicators). In order to support a comparative analysis and view, all the indicators have been rescaled on a rating spectrum from 0 to 100, in which “0” indicates the worst possible (theoretically and/or empirically) and “100” the best empirical value of measurement for the interpretation of democracy and quality of democracy (in the specific context of our 40-country sample here). For the process of rescaling the freedom of press and the Gini coefficient, we therefore had to shift reversely the value direction of the primary data, to make values (data) compatible with the other indicators. Results of that rescaling are being represented in Table 1. Data in Table 2 are arranged somewhat differently: there, the highest observed empirical value still is 100; “0,” however, is not the lowest possible value, but the lowest empirically observed value. Therefore, put in contrast, a comparison of the indicators in Tables 1 and 2 should allow for a better and more nuanced interpretation of the different countries and their quality of democracy (OECD, EU27). Mean values in Tables 1 and 2 are not weighted by population. Acronyms in Tables 1 and 2 have the following meaning: USA = United States and UK = United Kingdom. The comparison is based on a total of 11 indicators, in which the majority (more or less) fits nicely or at least convincingly into the 4 identified (basic) dimensions of democracy (see Fig. 1 in section “Conceptualizing Democracy and the Quality of Democracy: Freedom, Equality, Control, and Sustainable Development (Model of Quadruple Helix Structures)”). Such a broad indicator spectrum is used for an attempt “to determine a multi-layered quality profile of democracies” and could thus help, as put up for discussion by Hans-Joachim Lauth (2011, p. 49), to develop “qualitative or complex approaches for democracy measurement.” In the subsequent Tables 1 and 2, the empirical results are provided, and in what follows, the exact sources of indicators are being displayed and presented:

-

1.

The dimension of freedom: For this, political rights, civil liberties, and freedom of press are used as indicators as drawn up yearly by the Freedom House (2011c, d). Civil liberties play an important role, as they help allocate systems between primary electoral democracies and liberal democracies (with a higher quality of democracy). For political rights and civil liberties, the differentiated “aggregate and subcategory scores” are accessed. In some cases, controversial discussions take place concerning the reliability of Freedom House. But it appears that the methodology being used by Freedom House in the previous years has improved and Freedom House operates through a peer-review process that corresponds to the basic academic standards (Freedom House 2011a). Also, the Freedom House data related to OECD countries are less problematic than the data available regarding non-OECD countries. Moreover, Freedom House rates freedom in multiple countries as higher than that prevailing in the United States itself (see also the discussion by Pickel and Pickel 2006, p. 221). Additionally, data from the Index of Economic Freedom have been added (Heritage Foundation 2011). Regarding economic freedom, there appears to be a conflict or dilemma whether this should influence an evaluation measure (of freedom) of the quality of democracy .

-

2.

The dimension of equality: The choice rests on two indicators in this case. Regarding gender equality, the Global Gender Gap Index is referred to, as is being published annually by the World Economic Forum (Hausmann et al. 2011). As a comprehensive measure for gender equality, it covers the following areas: “economic participation and opportunity,” “educational attainment,” “health and survival,” and “political empowerment.” With respect to income equality, the Social and Welfare Statistics of the OECD (2011) are used for reference. Concerning the distribution of income, we decided to employ the “Gini coefficient” for the total population (“after taxes and transfers,” as the respective OECD source indicates; OECD 2011). The Gini coefficient is also known as the “Gini index.” Concerning the Gini coefficient (rescaled as income equality) in Tables 1 and 2, we interpreted 2009 as the approximate year of reference for the calendar year. The OECD online database (OECD 2011) speaks in this respect of the “late 2000s .”

-

3.

The dimension of control: The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is used in this regard, which is published yearly by Transparency International (2011). The CPI aggregates different opinion surveys and ranks countries according to the perceived level of corruption in a country. Corruption is (indirectly) used as an interpretation tool to measure the extent as to which the dimension of control is functioning (or not). The higher the values (data) for the Corruption Perceptions Index in Tables 1 and 2, the lower are the levels of perceived corruption .

-

4.

The dimension of sustainable development: The first choice rests on the Human Development Index (HDI), which is published regularly by the United Nations Organization (UNDP 2011). The HDI is calculated using the following dimensions: “long and healthy life,” “knowledge,” and “a decent standard of living.” The HDI therefore measures human development, which is one of the two basic principles that combine together with human rights to provide and explain the theoretical foundation and theoretical architecture of Guillermo O’Donnell (2004a) regarding the quality of democracy. As a second indicator, the aggregated “total scores” of the Democracy Ranking (2011) are considered. The Democracy Ranking 2011 calculates the average means for the years 2009–2010 and aggregates the different dimensions in the following way (Campbell 2008, p. 34): politics 50% and 10% each for gender, economy, knowledge, health, and environment (see also: http://www.democracyranking.org/en/). Thereby, the Democracy Ranking defines and analyzes sustainable development even more comprehensively than the HDI (Human Development Index). The “…Democracy Ranking displays what happens when the freedom ratings of Freedom House and the Human Development Index of the United Nations Development Program are being pooled together into a comprehensive picture”(Campbell 2011, p. 3) .

-

5.

Other indicators: Two indicators of the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) are adopted in comparing the quality of democracy (Huddleston et al. 2011): The “overall score (with education)” as well as the “access to nationality.” This index therefore measures the integration of immigrants and noncitizens, respectively, in a society and democracy. At first glance, it is not completely clear in which aforementioned dimensions (freedom, equality, control, and sustainable development) should the MIPEX be allocated. The possibility of multiple allocations is conceivable.

The International Comparison (Part Two): Comparison of the Years 2011–2012 and 2014–2015

The Democracy Ranking (http://democracyranking.org/wordpress/) represents an approach that tries to measure and compare quality of democracy in a global format and by applying a scientific model. For that purpose, quality of democracy refers to different dimensions (with different weights), and to those different dimensions, different indicators are being assigned. All indicator scores are transformed into a value (score) range of 1–100, where 1 implies the lowest and 100 the highest value (for quality of democracy). Normally, the Democracy Ranking compares two intervals of double years (where average values are being drawn for every double-year segment) (Campbell 2008).

More specifically, the Democracy Ranking 2016 compares the development of quality of democracy in 112 countries for the (two double) years 2011–2012 and 2014–2015. It is based on the following dimensions: politics (weighted with 50%), economy (10%), ecology and environment (10%), gender equality (10%), health and health status (10%), and knowledge (10%). The possible values that a country can achieve extend from 1 (the observed empirical minimum) to 100 (the observed empirical maximum) (the entire scale is thus 1–100).

The following key results of the Democracy Ranking 2016 should be emphasized (Campbell et al. 2017):

-

1.

The ten top-ranked countries for 2014–2015 are Norway (100.00), Switzerland (99.49), Sweden (98.45), Finland (98.04), Denmark (96.61), the Netherlands (93.41), New Zeeland (90.26), Germany (90.30), Ireland (89.57), and Australia (88.74).

-

2.

Improvement Ranking, the increase of quality of democracy: A relatively large progress (although often resulting from a lower level) was in several African countries (Ivory Coast, Madagascar, Senegal, and Burkina Faso), in Latin American in Nicaragua and Columbia, as well as in Tunisia. Tunisia is the only country of the Arab Spring that could realize a positive (and by tendency stable) path to more democracy.

-

3.

Improvement Ranking, the decrease of quality of democracy: A decrease can be observed for all the other countries of the Arab Spring (e.g., Libya and Egypt), as well as for Venezuela (in contrast to Columbia), and within the EU for Hungary. Furthermore the decrease of democracy in Turkey is remarkable and obvious. In Russia and China, the quality of the political systems has also decreased.

-

4.

Austria: Austria increased its scoring from 86.54 (2011–2012) to 87.76 (2014–2015) but slipped down slightly from rank 12 (2011–2012) to rank 13 (2014–2015). In international comparison, Austria ranks very high (rank 13 from 112 countries). However, a few of the other top-rated countries developed during the last years a faster dynamics than Austria. Freedom House rated the political rights for Austria during 2014–2015 stricter than still for 2011–2012.

-

5.

Possibly approaching problem region of the Balkans: The results of the Democracy Ranking also can be used in the sense of an early warning system for possibly arising problem situations. Serbia achieved an increase in quality of democracy (in the areas of politics, economy, and society), yet apparently not enough to improve its negotiation position for an EU membership. In Bosnia-Herzegovina and Macedonia, the scoring for economy and society improved, but in the area of politics, there was a decrease. Albania could increase its scoring for politics and society, but there was a decrease in economy. These recent trends in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia, and Albania require a more intensive international attention and observation.

Selected results of the Democracy Ranking 2016 (for the OECD and EU member countries) are summarized in Tables 3 and 4. Value scores have been adjusted to a value spectrum from “0” to “100,” where 0 represents the lowest observed empirical value and 100 the highest observed empirical value (for the completely covered time period of 2011–2012 and 2014–2015). Also changes in the quality of democracy scorings are indicated (improvements but also decreases) .

Conclusion: Quality of Democracy in Quadruple Helix Structures

Conclusion (Part One): Comparative Assessment and First Evaluation of Quality of Democracy in OECD Countries and the EU27 Member Countries

The following three research questions governed the analytical procedure of this chapter:

-

1.

To develop (in fact to prototype) a conceptual framework of analysis for a global comparison of quality of democracy. This framework will also reference to the concept of the Quadruple Helix innovation systems.

-

2.

In a second step, to use and to test this same conceptual framework for a comparative measurement of quality of democracy in the different OECD and EU27 member countries.

-

3.

In a final step, and based on the previous conceptual and comparative analysis, quality of democracy propositions for a democracy reform are being developed for democracy in Austria.

In theoretical and conceptual terms, we referred to a Quadruple-dimensional structure, also a Quadruple Helix structure (a “Model of Quadruple Helix Structures”) of the four basic dimensions of freedom, equality, control, and sustainable development, for explaining and comparing democracy and the quality of democracy.

What comes to mind, when looking at quality of democracy in reference to OECD and EU member countries, is the comparatively high ranking and positioning of the Nordic countries in Europe, particularly Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Denmark (see also on the web the newest and most recent scores of the Democracy Ranking 2016: http://democracyranking.org/wordpress/2016-full-dataset/). Also Switzerland places very high. The Nordic countries and Switzerland are also a good example for sustainable development, because they achieved and realized a development across different dimensions and indicators, so their progress is well-balanced. Of course, from a philosophical perspective, we always could speculate “how high is the high” of quality of democracy in the Nordic countries and in Switzerland from a “really timeless viewpoint.” But in “relative” empirical terms, no country or no democracy places higher than the Nordic countries and Switzerland (so far). So they define a practical and pragmatic benchmark for quality of democracy that already is accomplishable by countries. “The Nordic democracies (and Switzerland) demonstrate in empirical terms and in practice, which degrees and levels of a quality of democracy already can be achieved at the beginning of the twenty-first century” (Campbell 2011, p. 6).

In the following, we provide a first assessment for the quality of democracy in the United States, based on the empirical data that is strictly and consistently comparative in nature and character, and put forward first propositions. For the comparative assessment of the quality of democracy in the United States we can formulate the following tentative propositions. The United States ranks highest on the Human Development Index (dimension of sustainable development) and on political rights, economic freedom, civil liberties, and freedom of press, which means all dimension of freedom. Concerning the dimension of equality, the scoring of the United States is not that good anymore. With regard to gender equality, the United States positions itself slightly above OECD average, but concerning income equality, the United States performs clearly below OECD average. Concerning the perceived corruption, we already asserted that this indicator could be assigned to the dimension of control. In reference to the Corruption Perceptions Index, the United States scores higher (meaning to have less perceived corruption) than the OECD average but behind several of the more developed OECD countries. Concerning the data of the Democracy Ranking 2011 (dimension of sustainable development), the United States performs clearly above the OECD average. On the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX), the United States also scores above OECD average. Put in summary, we may conclude: the comparative strengths of the quality of democracy in the United States focus on the dimension of freedom and on the dimension of sustainable development. Further containment of corruption marks potentially a sensitive area and issue for the United States. The comparative weakness of the quality of American democracy lies in the dimension of equality, most importantly income equality. Income inequality defines and represents a major challenge and concern for democracy in the United States.

A different approach is to compare democracy in the United States (“American democracy”) not only with other individual (European) countries but with larger political-spatial entities, for example, an indicator-based aggregation of all of the member countries to the European Union (EU27), creating or approximating by this a version of “European democracy.” In that sense the whole United States also resembles an “aggregation”; therefore, it makes additionally sense to compare the United States with an aggregation of the EU member countries. Thought about this from a different angle, it also would be possible to compare the different (50) states of the United States individually with the different (national) member countries to the European Union. For the particularly aggregated comparison, we can propose a series of different propositions. It appears that US democracy is leading with regard to freedom and European democracy with regard to equality. While results for political freedom and gender equality are more mixed, the results for economic freedom and income equality are clearly more evident. In terms of economic freedom, the United States is ahead of (aggregated) Europe, and in terms of income equality, (aggregated) Europe is ahead of the United States (Campbell 2013). On political freedom and income equality, the EU15 is internationally more competitive than the EU27 (Campbell 2013, pp. 336, 340).

Does this mean that American democracy has specialized more on realizing freedom, while European democracy (despite national variations) places a greater emphasis on equality? Does this furthermore mark “archetypical” differences in political philosophy? Within the international system of global democracy, different democracies may have placed a different emphasis on different dimensions of quality of democracy, producing perhaps complementary effects for the overall worldwide further development of democracy. What is more important for democracy and quality of democracy, freedom or equality? Again in the long run, obviously, both dimensions, freedom and equality, matter, particularly for contributing to the perspective (dimension) of sustainable development. These differences in American and European democracy also stress the opportunity but also the real need of democracies, to learn mutually from each other (also as an expression of advanced political culture).

The following final propositions (in context of our current analysis here) can be put forward for further discussion for the further development of discourses that are interested to intertwine (“Inter-Helix”) quality of democracy with innovation and innovation systems:

-

1.

The basic Quadruple-dimensional structure of democracy and quality of democracy: The Quadruple Helix structure of quality of democracy identifies four basic (conceptual) dimensions for quality of democracy: freedom, equality, control, and sustainable development (Fig. 1). Particularly sustainable development marks here a new and innovative contribution to theory of democracy. Sustainable development also helps to avoid that models of measurement of democracy are biased toward a left-leaning or right-leaning ideological pole of political preferences. Sustainable development adds the important contribution of a more “neutral left/right balance” (Fig. 2). For sustainable development, knowledge and innovation play an important role, thus fostering the coming together of knowledge society, knowledge economy, and knowledge democracy . Components of knowledge can be research, education, and innovation (Campbell and Carayannis 2013b; Carayannis and Campbell 2012) .

-

2.

Quadruple Helix of quality of democracy and of innovation systems: Quadruple Helix qualifies as a concept with interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary capacities and capabilities. Quadruple Helix refers to the basic (conceptual) dimensions of democracy and quality of democracy. Quadruple Helix also represents the architecture of Quadruple and Quintuple Helix innovation systems, demonstrating, how knowledge and innovation processes in mature and advanced innovation systems are being progressed. Quadruple Helix fulfills here at least two crucial functions. (a) Knowledge and innovation are being defined as key for sustainable development and for the further evolution of quality of democracy. Knowledge and innovation are receiving an additional meaning and importance for democracy and theory of democracy. How to innovate (and reinvent) knowledge democracy? Democracy discourses and innovation discourses develop further in mutual cross-reference. (b) The other crucial function of the Quadruple Helix is that it demonstrates that the context of society and of democracy is important for innovation systems (Campbell and Carayannis 2016). The unfolding of an innovative knowledge economy also requires (at least in a longer perspective) the unfolding of a knowledge democracy . So there is also a “perspective of democracy” for advancing innovation systems. “Democracy of knowledge” plays in both ways (Carayannis and Campbell 2012).

-

3.

There is no Quadruple or Quintuple Helix innovation system without a democracy: Pre-Quadruple Helix innovation systems (such as the Triple Helix) can be applied in very different political environments. Triple Helix is possible in combination with democratic or nondemocratic political regimes. The Quadruple Helix is here more specific and concrete. The architectures of Quadruple Helix and Quintuple Helix innovation systems demand and require the formation of a democracy, implicating that quality of democracy provides for a nurturing of innovation and innovation system, so that quality of democracy and progress of innovation mutually “Cross Helix” in a connecting and amplifying mode and manner. In a win-win scenario, quality of democracy, and innovation systems, they both cross-link and coevolve. “The way how the Quadruple Helix is being engineered, designed, and architected clearly shows that there cannot be a Quadruple Helix innovation system without democracy or a democratic context” (Carayannis and Campbell 2014, p. 19). This relates research on quality of democracy to research on innovation (innovation systems) and knowledge economy (see also Carayannis et al. 2018). The one matters for the other. “Cyber-democracy” receives here a new meaning (Campbell and Carayannis 2014) .

Conclusion (Part Two): Recommended Measures for Improving Quality of Democracy Reform in Austria

There are several analyses that reflect on Austrian democracy and the Austrian political system by referring (in greater detail) to a wider spectrum of themes: Beetham (1994), Campbell (2002, pp. 30–31, 39; 2007, pp. 392–393, 402; 2011; 2015b), IDEA (2008), Müller and Strøm (2000, p. 589), Pelinka (2008), Pelinka and Rosenberger (2003), Poier (2001), Rosenberger (2010), Sickinger (2009), Valchars (2006), and Wineroither (2009).

We want to focus now more specifically on Austrian democracy. For an assessment (evaluation) of the quality of democracy in Austria, we set up for discussion the following propositions in context of a dynamic thesis formulation (furthermore, see also Campbell 2015a, b):

-

1.

Comparatively, Austria’s quality of democracy yields good results in political rights and civil liberties (dimension of freedom), income equality (dimension of equality), and within both indicators for the dimension of sustainable development.

-

2.

Comparatively, Austria’s quality of democracy yields less good results in freedom of press and economic freedom (dimension of freedom), gender equality (dimension of equality), and corruption (dimension of control).

-

3.

Comparatively, Austria’s quality of democracy yields lower-ranking results in both indicators used in the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) that show a problematic positioning. Austria’s comprehensive rank in the MIPEX is only at 26 out of 33 (here are behind Austria only Bulgaria, Lithuania, Japan, Malta, the Slovak Republic, Cyprus, and Latvia), and in the category of access to citizenship, Austria ranks only at 30 out of 33 (here, only Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia perform poorer than Austria) (see Tables 1 and 2). However, in relation to this observation, it must be noted that the poor performance of Austria in the MIPEX is not negatively reflected by the Freedom House’s freedom rating in the category of political rights and civil liberties. One proposition would be that the integration of foreigners and of noncitizens (but being born and living exactly in the country, where they are) is not given enough weight (by Freedom House).

The comparative strengths and weaknesses of the Austrian quality of democracy blend themselves differently along the dimensions of freedom and equality. Regarding sustainable development, Austria’s quality of democracy finds itself ranked highly, and its position remains robust. Taking the ratings of the Democracy Ranking during the years 2009 and 2010 under consideration (Democracy Ranking 2011), countries like Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Switzerland find themselves worldwide on top in the category of sustainable development. Therefore, currently, the Nordic countries provide the global empirical benchmark for democracy development (for a comprehensive and sustainable democracy development). The Nordic countries have impressively demonstrated the level for the quality of democracy that is empirically already possible to achieve. “The Nordic democracies (and Switzerland) demonstrate in empirical terms and in practice, which degrees and levels of a quality of democracy already can be achieved at the beginning of the twenty-first century” (Campbell 2011, p. 6).

As compared with the OECD countries, the quality of democracy in Austria is ranked high to very high, but not in all dimensions and for all indicators. Evidently, for the purpose of a further learning with respect to the quality of democracy in Austria (so the proposition), the identification of the potentially problematic areas appears to be relevant above all, since, naturally, those areas require democratic and political reform. In Austria, necessity for innovation and democracy innovation is drastically needed in freedom of press, in gender equality, and in fighting and containing corruption. However, the most urgent action plan for Austria’s quality of democracy needs to be implemented particularly in the improvement of integration of immigrants and of non-EU citizens and a better access to citizenship. Integration policy is also linked, interlinked and cross-linked with other policy fields such as asylum policy (Rosenberger 2010). Austria’s citizenship law knows no jus soli but is directed and steered by a pure jus sanguinis policy. Automatic acquisition of Austrian citizenship still only takes place through the Austrian citizenship of the parents (jus sanguinis), whereas birth in Austria (jus soli), also residence during childhood and youth, are being completely ignored. Persons, who are not Austrian citizens, of course can always apply for Austrian citizenship (when specific conditions are being met and fulfilled), but this is something else than an automatic acquisition of citizenship. Therefore, descent (in essence also a biological principle) actually decides about political rights and automatic political participation in Austrian democracy. This only can be hardly balanced with the developed quality standards of a democracy in the twenty-first century and, when given further thought, stands finally in contradiction to fairness and universal equality of people and the general application of human rights. According to Pelinka (2008), there is a need in Austria for a more systematic conceptual reflection on the demos, in the sense of “Who are the People?” (“Wer ist das Volk?”). This reflection should definitely encourage more inclusion (see also Valchars 2006). Reforms in citizenship law in other European countries (such as in Germany), in the recent years, did not enter into Austrian politics and were not taken up by the Austrian mainstream political discourses. Should Austrian politics continue the blocking of an introduction of a jus soli component into its citizenship law during the course of the coming years, then it cannot be ruled out completely that the pure jus sanguinis design will finally be challenged legally at a “constitutional court” (nationally, supranationally, or even internationally). Here we can quote also from an original source: “Bedenklich für Demokratiequalität ist, wenn ein bedeutender Anteil der Wohnbevölkerung nicht im Besitz der Staatsbürgerschaft ist beziehungsweise sich dieser Anteil sogar vergrößert: Denn das könnte dazu führen, dass manche Parteien, die an Wahlstimmenmaximierung interessiert sind, den StaatsbürgerInnen ‘auf Kosten’ der Nicht-StaatsbürgerInnen Wahlversprechen geben. … Je größer der Anteil der Nicht-StaatsbürgerInnen, desto höher fällt das populistische Potenzial für den Parteienwettbewerb aus. Soll gegen Populismus ein effektiver Riegel vorgeschoben werden, müsste der Anteil der Nicht-StaatsbürgerInnen an der Wohnbevölkerung möglichst verringert werden” (Campbell, 2002, pp. 30–31) .

The following possibilities for a betterment and quality of democracy reform of Austrian democracy and politics are to be sketched and presented for a qualified (and necessary) discussion:

-

1.

Citizenship: The introduction of an equal and equitable jus soli component in Austrian citizenship law, parallel to the current jus sanguinis component, appears to be absolutely necessary. Jus soli would at least imply that a person, who has been born in Austria, is being regarded automatically as an Austrian citizen. Sufficient residence in years during childhood and youth may also be acknowledged. To address the possibility of dual and multiple citizenship, different scenarios are conceivable and naturally legitimate; there are, however, good arguments in favor of introducing and approving dual and multiple citizenship .

-

2.

Gender equality, freedom of the press, better integration of immigrants (non-EU citizens), and containment of corruption: These are areas and policy fields of concern in which Austria does not position itself as well as we should expect. Reform of Austrian democracy should therefore focus more intensively on these “hot spot” topics and fields of policy application (on the financing of politics and political parties in Austria, see, e.g., Sickinger 2009) .

-

3.

Balancing of political power: For Western Europe, Wolfgang C. Müller and Kaare Strøm (2000, p. 589) empirically enumerated and calculated the higher-risk ruling parties which are exposed to in upcoming elections of losing, rather than maintaining their share of votes. That would, therefore, be a manifestation of the phenomenon of government/opposition cycles and of political swings (left/right swings) that occur regularly in democracies. A particular feature of the Austrian national parliament (“Nationalrat”) is the existence of a “right” mandate majority of center-right and right-wing parties since the parliamentary election of 1983. Conversely, it can be argued that possibly in reaction to the conservative federal governments (in coalition arrangements of ÖVP/FPÖ and ÖVP/BZÖ parties), on the federal level during the years 2000–2007, for the first time ever a “left” majority at the sub-federal provincial level resulted after 2005, when the political party composition of the nine provincial parliaments (“Landtage”) is being aggregated together and also is being weighted on the basis of population in these provinces (Campbell 2007, pp. 392–393). For an analysis of the Austrian federal governments in these respective years, see furthermore Wineroither (2009). The current continuation of grand center coalitions of the center-left social democrats (SPÖ) and the center-right conservatives (ÖVP) on the federal level suggests perhaps a starting erosion of the combined left majorities at the provincial level. For an improved political balance of power, the possibilities and recommendations are increased application of term limits to political office (also for chancellors and heads of provincial governments, the governors), general elimination of automatic proportional representation of political parties in provincial governments based on the number of their mandates in the provincial parliaments (called in Austria “Proporz”), and general introduction of direct popular elections of mayors, possibly also direct popular elections of the heads of provincial governments, i.e., the governors (paralleled by a rearrangement of the current political balance of power on provincial level) (Campbell 2007, p. 402; see also Jankowitsch 2013). For a possible reform of the electoral law, see Klaus Poier (2001) and his considerations in favor of a “minority-friendly majority representation” (“minderheitenfreundliches Mehrheitswahlrecht”). The mentioned and indicated “institution of term limits” would also have had effectively prevented a phenomenon such as that of Silvio Berlusconi in Italy, where a person (with “inter-interruptions”) exerted the function of Prime Minister over almost 20 years (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silvio_Berlusconi). There also could and can be “Berlusconi” phenomena in other (Western) democracies, especially when there is no institutionalization and implementation of term limits .

-

4.

Referendums: Should a public petition with a minimum number of signatures automatically be subjected to a referendum? (Should the parliament, with a “qualified majority,” be able to object to it?) The following points speak against an increased application of referendums: politics (political cycles) would be too short-lived, blockade of further EU integration processes with an interest in deepening the European Union (by scapegoating EU policies at the national level), and a populist abuse of certain political themes (e.g., against immigrants). However, the fact that the national population or the voters would have the power to put forward a topic on the political agenda which may otherwise would be ignored by the ruling parties (or the parties in parliament), is a point that speaks in favor for the increased application of referendums. Therefore, the specific setting of a minimum number of signatures for a public petition would be an important decision. Two hundred fifty thousand signatures would probably not suffice. Six hundred forty thousand signatures (around 10% of the voters in Austria) perhaps may be sufficient. This reference bar could also be raised higher though, for example, to 25% of the voters (Campbell 2002, p. 39). In variation of this, there also could be a direct democracy design, where every public petition with a required minimum number of supporters would not be linked to a “binding” referendum (Volksabstimmung) but only to a “non-binding” or consultative referendum for advisory functions (Volksbefragung). More generally speaking, direct democracy approaches are possible at the national (federal) level in Austria, however, also at the subnational (regional) levels of the Austrian political system .

-

5.

Political education (civic education): In the Austrian education system (for instance, the secondary school), political education (civic education) should be introduced comprehensively and uniformly as a distinct subject (“Unterrichtsgegenstand”). Political education would therefore let itself conceive as a form of “democratic education” and may be reconceptualized as a “democracy education” (as well as be renamed this way?) .

-

6.

“Democratic Audit” of Austria: The political system of Austria, its democracy and quality of democracy, have so far not undergone a systematic democratic audit. Attempts of the Austrian political science community, to convince Austrian politics and Austrian politicians to support such a democratic audit of Austria, were so far not successful. For this purpose, for example, the procedure of IDEA could be used and be applied (see IDEA 2008; Beetham 1994). However, it would also be possible to hybridize or pool different procedures (for the interesting example of a performed democratic audit in Costa Rica, see Cullell 2004) .

Epilogue on Cyber-Democracy

Advanced democracies or democracies of a high quality are also a “knowledge democracy.” One underlying understanding here is that knowledge, knowledge creation, knowledge production, and knowledge application (innovation) behave as crucial drivers for enhancing democracy, society, and the economy. “Cyber-democracy” = a manifestation of knowledge democracy, where IT (information technology) and ICT (information and communications technology) matter. However, cyber-democracy is more than an IT (ICT) concept. “Cyber-democracy” is to look at a knowledge democracy from the perspective of a globally evolving knowledge society and knowledge economy in configurations of a multilevel architecture (top-down from global to transnational, supranational, national, subnational, and local).

The research question of our analysis focused on conceptualizing and measuring quality of democracy in international and global context. In particular, we put the two country-based democracies of the United States and of Austria into comparison. The OECD countries served as the general frame of reference for context. Now, how does cyber-democracy relate to democracy and the quality of democracy? In our opinion, this represents a new and challenging field, which requires further elaboration. The evolution of cyber-democracy still is at the very beginning. There are all the potentials for surprises in the flow of the coming events. In the following, we want to present a few propositions on cyber-democracy and the tendencies that are possibly involved and may unfold. These propositions we want to suggest as reference points for further discussions and discourses on cyber-democracy :

-

1.

Cyber-Democracy and Knowledge Democracy: The progress of advanced economies and of quality of democracy depends on knowledge economy, knowledge society and knowledge democracy, their coevolution, and their mutual interlinkages (Carayannis and Campbell 2009, 2010, 2012; Campbell and Carayannis 2013b). The transformation and shift has been from a knowledge-based economy and society directly to a knowledge economy and knowledge society. Pluralism and heterogeneity are crucial and decisive for progressing quality of democracy. The analogy to knowledge is that advanced knowledge systems are also characterized by a pluralism, diversity, and heterogeneity of different knowledge paradigms and innovation paradigms that drive in coevolution the interaction and relationship of competition, cooperation, and learning processes. Cyber-democracy, in fact, amplifies and accelerates the momentum of knowledge democracy. Cyber-democracy is connected to democracy by building and by forming IT-based infrastructures and public spaces, where IT (information technology) helps in creating new types and new qualities of public space. The concept and model of the “Quadruple Helix innovation system” (Carayannis and Campbell 2009, 2012) identifies the “media-based and culture-based public” (in addition to “civil society”) as the one crucial helix or context for carrying on and advancing knowledge production and innovation. Therefore, in these aspects, the cyber-democracy and knowledge democracy overlap in a conceptual understanding but also in the manifestation of empirical phenomena. Cyber-democracy expresses a particular vision, for how knowledge democracy may evolve further in certain and particular characteristics. IT-based public spaces in cyber-democracy operate nationally and subnationally. Cyber-democracy, however, also transcends the boundaries of the nation state, as such adding to the building of a transnational, in fact global, public space. Public spaces in cyber-democracy are certainly multilevel (global, national, and subnational). The global and transnational aspect of public space in cyber-democracy certainly represents this one very new and radical aspect, allowing for a global spreading of knowledge and of high-quality knowledge, in this case enabling continuous flows of knowledge and discourses beyond the limits of the nation state .

-

2.