Abstract

With regard to the perspectives of human capital, university status and role identity, I investigate how the career paths of academic entrepreneurs can influence university spin-off growth. The results from the qualitative content analysis and extreme case analysis show that each university status comprises certain advantages and disadvantages. Academic entrepreneurs are located in a trade-off. More human capital and a higher university status are not necessarily advantageous for long-term university spin-off growth. Instead, the willingness and ability for role identity change in terms of the degree of commitment to the entrepreneurial role is very important. Therefore, it is important to consider the career plans and growth intentions of an academic entrepreneur. In order to compensate certain disadvantages of different university statuses the formation of founding teams with complementary skills and university statuses should be promoted.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Universities are increasingly seen as engines for regional innovation and economic growth (Lawton Smith 2007; Etzkowitz 2008; Mustar et al. 2008). Some famous high-tech regions have evolved on the basis of universities, for example, Silicon Valley in California, Greater Boston in Massachusetts, or the Research Triangle in North Carolina (Saxenian 1983; Sternberg 1995). In these regions, university spin-offs are regarded as one important vehicle of knowledge transfer and commercialization from university to industry. Furthermore, empirical studies confirm that university spin-offs have a higher employment growth (Egeln et al. 2002; Czarnitzki et al. 2014) and a higher survival rate (Lawton Smith and Ho 2006; Zhang 2009) compared to average firms. This benefits regional development and is therefore a key interest among policy makers.

The focus of this paper is on the individuals who are behind these processes, those academic entrepreneurs who develop great ideas at a university and decide to put them into practice. One famous example is the Stanford University Ph.D. Student Larry Page, who founded the internet search engine Google (Shane 2004). Academic entrepreneurs do not comprise a homogeneous group. Depending on the time they have spent in university before founding a university spin-off, they have been through different university career paths and so they can be students, research staff, or professors. The aim of this paper is to investigate how academic entrepreneurs’ university career can affect university spin-off growth. For this purpose, research questions were derived from three conceptual perspectives: university status, human capital, and role identity.

The relationship between the career paths of entrepreneurs and growth intentions is still inconclusive. While some quantitative studies deny an influence (Kolvereid 1992; Birley and Westhead 1994) others empirically prove it (Cassar 2007). Obviously, this relationship can hardly be investigated by quantitative analysis, because career paths are quite complex. They extend over a long period of time and many career decisions are path dependent and interrelated, so that they can hardly be forced into predefined rigid independent variables (Kodithuwakku and Rosa 2002; Druilhe and Garnsey 2004). For these reasons, my empirical analysis is based on qualitative survey data from 87 academic entrepreneurs of two German universities. The analytical process relied on a qualitative content analysis and extreme case analysis.

This paper is structured as follows: First the three conceptual perspectives are discussed and two research questions are derived. After introducing the data and methods used in this paper, the empirical results of the qualitative content analysis and extreme case analysis are discussed. Finally, a conclusion is drawn including the contribution of the study to literature, implications for policy and further research as well as limitations.

2 Conceptual Framework

In order to comprehensively explain the relationship between academic entrepreneurs’ career paths and subsequent university spin-off growth three streams of literature are relevant: the university status perspective, the human capital perspective, and the role identity perspective. The first and last perspectives were also selected by Ding and Choi (2011), who investigated the influence of scientists’ career paths on their decision to create a venture or join a scientific board. The human capital perspective is for example also used by Müller (2006) for explaining the success of university spin-offs.

2.1 University Status Perspective

Founding a university spin-off is an outstanding event in the life of a scientist. Normally scientists reflect intensely before taking this step: if they want to take the risk, what they might lose, and what their social network would think about the decision. It is important to keep in mind that university spin-off creation is still considered to be a controversial behavior in certain universities and areas of studies in Germany (Dörre and Neis 2010). In contrast to the United States, the prospects of returning to academia after leaving university to start up a university spin-off are quite low in Germany (Wentland et al. 2011).

With advancing time in university, scientists are likely to climb up the university hierarchical ladder. Empirical studies prove that an individual’s position in the status hierarchy (bottom-, middle-, and top-status) influences his conformity (see for example Phillips and Zuckerman 2001). It may therefore be reasonably assumed that a scientist’s university status influences both the decision to create a university spin-off as well as subsequent university spin-off growth.

At the beginning of the university career, individuals have usually little to lose. They are open for new adventures and willing to take risks because they still do not belong to a specific social group where certain norms are expected. This freedom enables them to generate extraordinary innovations apart from social group norms (Phillips and Zuckerman 2001), which can be advantageous for university spin-off growth. However, this also leads to certain disadvantages. Low university status entrepreneurs do not possess a social network, which enables them to access resources and information easily. This might hinder university spin-off growth.

At the middle level of a university career, academics want to belong to a certain social group which makes them quite dependent on external expectations. The fear of disenfranchisement makes them act quite conservatively (Phillips and Zuckerman 2001). On the one hand they have already reached a certain status that they would risk, losing. On the other hand they have not gained the reputation and resources to an extent that gives them the security and freedom as is the case for high status entrepreneurs (Phillips and Zuckerman 2001). Nevertheless, it can be assumed that middle university status entrepreneurs possess more reputation than low university status entrepreneurs. This makes it easier for them to overcome the liability of newness (Garnsey 1998) and foster university spin-off growth. Also, they have a wider social network than low university status entrepreneurs, which also facilitates the access to relevant resources as long as the university spin-off matches existing social group norms (Phillips and Zuckerman 2001).

Individuals with a high university status, especially star scientists, usually possess good access to resources and information to be able to cope with and evaluate the risks connected with founding a university spin-off (Phillips and Zuckerman 2001). They enjoy a high level of reputation within their field and social network. This makes it easier for them to gain initial credibility, acquire funding, and attract customers (Shane 2004), which is advantageous for university spin-off growth. Following Phillips and Zuckerman (2001) it can be assumed that high university status entrepreneurs tend to exploit opportunities, which are in line with the norms of their social network.

In summary, with increasing university status, reputation and access to resources through the social network usually increase (Ding and Choi 2011), which in turn is advantageous for university spin-off growth.

2.2 Human Capital Perspective

According to the human capital theory, individuals are endowed with skills and knowledge and can increase their overall knowledge through investments in their human capital like schooling, on-the-job-training, searching for information, etc. (Becker 1975). Early in the academic life cycle, scientists invest in their human capital in order to gain scientific expertise in a specific subject. This usually happens through basic science research. After achieving important milestones scientists create a university spin-off to exploit their research results or specific competencies they have acquired in order to get financial returns on their human capital (Shane 2004; Ding and Choi 2011). This argument also received empirical support (Klofsten and Jones-Evans 2000).

In the field of entrepreneurship, investments in human capital are usually seen as an advantage in terms of a company’s survival, growth, and profitability (Shane 2004; Stützer 2010; Parker 2005; Colombo and Grilli 2005). However, Lazear (2005) differentiates between employees and entrepreneurs. While employees tend to be specialists in their field, entrepreneurs should rather be a Jack-of-all-Trades. This means entrepreneurs have to combine different skills. Large investments in one special subject are an obstacle for becoming a successful entrepreneur. According to Lazear (2005), it is quite obvious that scientists obtain expertise in their field, but this kind of knowledge alone is not sufficient. Furthermore, large investments in human capital for example lead to a higher risk aversion and higher opportunity costs (Davidsson and Honig 2003). Especially in the context of university spin-offs a positive relationship between human capital acquisition in a university and a university spin-off’s success is not inevitable (Mason et al. 2011; Helm and Mauroner 2007; Wennberg et al. 2011), because at a certain point in time the danger of a cognitive lock-in might develop (Murray and Häubl 2007).

The acquisition of scientific expertise in a university is strongly related to the specificity of the university knowledge applied in the university spin-off. Regarding the degree of knowledge, transferred literature distinguishes exploitation spin-offs, competence spin-offs, and academic start-ups (Bathelt et al. 2010; Egeln et al. 2002; Karnani and Schulte 2010). Exploitation spin-offs are based on concrete research results or novel methods, which at least one academic entrepreneur has developed at a university. Competence spin-offs emerged from specific knowledge or skills, which at least one academic entrepreneur has acquired in a university. The academic entrepreneur’s specific competence enables him or her to develop the original idea further, oftentimes even independently from the university. By contrast, academic start-ups comprise only generic knowledge or skills, which at least one academic entrepreneur has acquired in a university (Egeln et al. 2002). An empirical study for Germany discovered that external stakeholders react more constrained to university spin-offs of high status inventors, who want to exploit research results. This is because firstly, exploitation spin-offs need a large team with various competencies. Therefore, the sales productivity is quite low in the first years. Secondly, standardization and economies of scale for exploitation spin-offs are difficult to achieve (Egeln et al. 2002).

2.3 Role Identity Perspective

Scientists and entrepreneurs have in principle two opposite value systems and academic entrepreneurs obviously operate within this area of tension (Szyperski and Klandt 1981). These opposite value systems are reflected in the scientists’ and entrepreneurs’ attitudes and behaviors. The respective mentality is firmly anchored in their minds and cannot be changed easily. This means that scientists have to shift their roles to become successful academic entrepreneurs (Jain et al. 2009). Chandler and Jansen (1992) for example identified three different roles a founder has to adopt: an entrepreneurial, a managerial, and a technical–functional role. Entrepreneurs act in a highly competitive market environment. They seek market success through profit orientation and market acceptance. In utmost contrast, scientists act in an environment far apart from economic constraints which gives them the opportunity to pursue independent research. They are used to writing applications for research projects to acquire funding and they are mainly interested in a technological success (Stephan and Levin 1996). German scientists improve their reputation mainly through own publications in highly specialized journals and secondly through teaching, whereas patenting, technology transfer and entrepreneurial activity are less important (Wentland et al. 2011). So if scientists transfer their academic habits to their new roles as entrepreneurs, they might fail to orientate to the market and to force economic success through identifying buyers and making marketing (Nörr 2010).

Erdös and Varga (2012) rightly state that empirical studies hardly consider the role of scientists as entrepreneurs. Adopting new roles is a difficult task especially for scientists, who pass through a long-term university career before founding a university spin-off. Due to the long and intense socialization process in a university (Ding and Choi 2011), they have another entrepreneurial attitude than students or doctoral students, who might have never planned to work for the university for a longer time and who did not internalize the university value system in such intensity (Mangematin 2000). Therefore, it can be generally expected, that doctors and professors have both a lower entrepreneurial and profit orientation. Therefore, they might create university spin-offs with less growth potential.

Scientists, who stayed in a university for a long time, identify themselves to such an extent with their academic role that they are able or not willing to change it even after founding a university spin-off. This persistence of identity can lead to the situation that the academic entrepreneur wants to stay in a university and run the university spin-off only part-time (Braun-Thürmann et al. 2010; Nicolaou and Birley 2003; Jain et al. 2009). Empirical evidence exists that it is important whether an academic entrepreneur has left the university to set up a company or not (Pirnay et al. 2003; Shane 2004). Heading the university spin-off only on a part-time basis bears the risk of reducing personal commitment and thereby growth expectations (Egeln et al. 2002; Doutriaux 1987).

2.4 Developing Research Questions

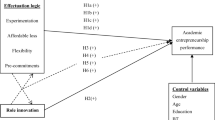

In the conceptual discussion the importance of an academic entrepreneur’s career path for university spin-off growth was explained through three different perspectives. Career paths are quite complex, as the above described conceptual perspectives result in competing expectations for university spin-off growth (see Fig. 3.1). Furthermore, career paths extend over a long period of time and can contain breaks. For these reasons, it is appropriate to base the empirical analysis on a qualitative research design. Qualitative research generally focuses on analytical instead of statistical generalization (Miles and Huberman 1994). In the following analysis of the career paths of academic entrepreneurs I investigate:

-

1.

How the university status, human capital, and role identity influence university spin-off growth.

-

2.

How the university status, human capital, and role identity interact with each other.

3 Data and Methods

Different approaches for collecting and analyzing qualitative data exist (Bernard and Ryan 2009). With the means of a qualitative content analysis I first investigate how the university status, human capital, and role identity separately influence university spin-off growth. In order to determine university spin-off growth, I look at the number of employees. For this analysis I use the whole sample. Then I conduct a comparative analysis of selected extreme cases. I identify three academic entrepreneurs of high growth university spin-offs and three academic entrepreneurs of low growth university spin-offs with similar career paths and analyze their career paths in depth. In this way it is possible to show the importance and interaction of the three perspectives.

3.1 Defining Academic Entrepreneurs

Following Pirnay et al. (2003) and Smilor et al. (1990) I defined academic entrepreneurs as scientists or students who left a university to start a company or who founded (or co-founded) a company while still affiliated with a university to exploit their knowledge and/or skills acquired at university in a profit-making perspective. Accordingly, the companies created are called university spin-offs. In contrast to some other authors, who only consider technology-oriented university spin-offs in their studies (see for example Smilor et al. 1990), I take a broader view of knowledge transfer by including academic entrepreneurs of knowledge-intensive service companies (see for example also Rappert et al. 1999).

I analyze university spin-offs which were founded from 1980 until 2011. The time between leaving a university and the official business formation did not exceed a maximum of 3 years because this study investigates spin-offs based on university knowledge. The temporal boundary of a maximum of 3 years is a good compromise. On the one hand I avoid taking entrepreneurs into account, who gained significant knowledge in the private sector (Pirnay et al. 2003; Wennberg et al. 2011). On the other hand a sufficient time period is necessary for setting up a company, especially in high-tech sectors.

3.2 Data Collection and Sampling Approach

A wide range of literature already exists on top universities and regions like Silicon Valley in California, Greater Boston in Massachusetts, or the Research Triangle in North Carolina (Saxenian 1983; Sternberg 1995). In this paper, the cases were drawn from the two biggest universities in Lower Saxony, Germany with regard to the total number of students,Footnote 1 the number of students in subjects which are common for university spin-offs,Footnote 2 the number of scientific staff, and research expenditures (Kulicke et al. 2008). The two chosen universities, Hannover and Göttingen, are particularly suitable examples for German mid-range universities located in regions outside high-tech clusters. At this kind of university individual characteristics and career paths play an important role for university spin-offs, because only a weak entrepreneurial support structure exists.

Since the data on university spin-offs in Germany is far from being accurate, the data used in this paper was collected within the framework of a broader research project.Footnote 3 The current study should therefore also give an overview on university spin-off activities at the two chosen universities. For this reason a more comprehensive approach to data collection was chosen compared to other qualitative studies (Baker and Edwards 2012). In order to identify as many academic entrepreneurs as possible the total sample of university spin-offs for the two universities was composed as follows:

In the first step of data collection I had informal discussions with leaders of the technology transfer offices and employees of different economic development agencies in the two survey regions Hannover and Göttingen. I also asked the heads of all institutes of the two universities for information about university spin-offs by mail in order to avoid a bias for the benefit of university spin-offs which used advice on funding and financing matters. Furthermore, I initiated a search operation through the business network XING in order to capture any university spin-offs, which had contact neither with the current faculty staff nor with the technology transfer offices nor with employees of different economic development agencies.

The second step of data collection was a validation of all contacts I collected by e-mail and further internet searches. In many cases it was not clear if a business was from an academic entrepreneur according to our definition. In total, I obtained a list of 334 academic entrepreneurs. From this population, 152 academic entrepreneurs were asked for an interview. Sixty-five were unresponsive or did not agree to an interview. A sampling grid was used to ensure a heterogenic sample structure (Schreier et al. 2007; Bernard and Ryan 2009). The cases were equally distributed throughout the two basic categories: students or scientists.Footnote 4

In the third step of data collection, I had semi-structured face-to-face interviews with 87 academic entrepreneurs (Bernard and Ryan 2009) during the period of September 2011 to January 2012. The face-to-face interviews usually took place in the respective company and ranged from 45 min to 2½ h in length.Footnote 5 The vast majority of interviews was openly recorded and directly transcribed.Footnote 6 Throughout the interviews, I asked open-ended questions pertaining to the chronological career path before the university spin-off as well as the phases of preparing, establishing, and developing the university spin-off (Vohora et al. 2004; Roberts and Malone 1996; Rasmussen 2011). During and after the interviews the interviewer took field notes. Furthermore, a post-interview questionnaire and information collected from the university spin-off websites and press articles augmented the data.

3.3 Data Coding and Analysis

In the first step, I conducted a qualitative content analysis with all 85 transcribed interviews (Mayring 2008; Gläser and Laudel 2009) which was supported by the qualitative data analysis software NVivo. Table 3.1 shows important factors derived from the three conceptual perspectives. In the qualitative content analysis these factors were considered.

In order to differentiate different university statuses I developed six categories which show the university status of every academic entrepreneur at the time of the university spin-off creation. The different university statuses are categorized as follows: (1) “Students” who were still studying at the university. (2) “Graduates” who founded the university spin-off after graduating from the university. (3) “Doctoral students” or research associates without a doctor’s degree. (4) “Doctors” who had already achieved the doctoral degree and left the university. (5) “Postdoctoral fellows” who worked at a university after achieving the doctoral degree. In most cases the individuals were working on their habilitation.Footnote 7 (6) “Professors” including private lecturers, adjunct professors and emeriti. In this category the individuals had finished their habilitation.

On the basis of the qualitative content analysis of all interviews, I conducted a comparative extreme case analysis in the second step. Therefore I identified three academic entrepreneurs of high growth university spin-offs and three academic entrepreneurs of low growth university spin-offs measured according to the increase of employees (see Fig. 3.2 ).Footnote 8 These six academic entrepreneurs are combined to three pairs with very similar career paths but very different university spin-off growth. This approach is especially useful for a contrasting comparison and an identification of the possible best practice. Although high growth university spin-offs are rather rare in our samples, they are of course the most favored by policy makers and most eligible for support because they have a high influence on regional economic growth. In contrast, low growth university spin-offs have a weak influence on regional economic growth but they occur more frequently and also contribute to regional economic diversity and innovation (Cohen and Klepper 1992). The selection of extreme cases shows more specifically how the career paths of academic entrepreneurs contribute to university spin-off growth.

Identification of extreme cases measured according to university spin-off size. Note: N = 85. One case corresponds to one university spin‐off. Number of employees is based on full‐time equivalents. Categorization of enterprises in accordance with the Federal Bureau of Statistics (2013). Selected cases for extreme case study highlighted in yellow and green. Source: Own survey 2011

4 Results of the Qualitative Content Analysis

Based on the conceptual perspectives discussed above and by using a qualitative content analysis, I show how university status, human capital and role identity can affect university spin-off growth. The results for each conceptual perspective are explained in individual chapters and different university statuses are addressed.

4.1 Results from the University Status Perspective

In the following, I present the results concerning the expectation that academic entrepreneurs with a higher university status may be more likely to find a high growth university spin-off. I discuss the advantages and disadvantages of low, middle, and high university status entrepreneurs successively.

Low status university entrepreneurs who start a university spin-off, such as students and graduates, have low entry barriers. In accordance with the theoretical assumption, several of them reported that they were used to coping with little income anyway and were willing to take risks, as the following quotation of a graduate indicates: “Now we are studying and get along with little money. Now we can see what happens if we start a company with ideas which were brought to the university’s attention but cannot carry out.” (USO08). This quotation also indicates that students are still quite flexible, which is also in line with the theoretical assumption. At the beginning of a university career, an individual is also more willing to learn something new and to adapt to new situations quickly. Low status academic entrepreneurs have only little responsibility in their private and professional lives and have more freedom. On the other hand, some students and even graduates had to cope with legitimacy problems in the first years, as one student reports: “We had the image of a students’ firm for many years. We had to fight for a long time. Especially the authorities did not take us seriously, although this was actually unfounded after a certain initial phase.” (USO04). In some sectors, like information technology, a young, dynamic firm’s image might not be an obstacle, but in other sectors, such as scientific and technical services, it is. Established scientists normally do not have to cope with such prejudices.

Middle university status entrepreneurs, such as doctoral students, also enjoy a high degree of freedom because in Germany they usually have part-time contracts. They can plan the rest of their time relatively freely, as this doctoral student states: “With a professor, who would have said: ‘If you do not work on your thesis for 100 % I will dismiss you!’, we would have had a problem.” (USO74). Nevertheless, the triple burden of working in a university, writing a doctoral thesis and establishing a university spin-off is often a hard struggle for doctoral students. This struggle becomes even harder, the more successful a university spin-off becomes. As a result, it may take doctoral students longer to finish a thesis. In some cases they may quit their academic career, as one third of the doctoral students in the sample did. Nevertheless, having a doctoral degree of course bears several advantages which make it possibly worthwhile to finish a doctorate before founding a university spin-off. For example, customers often have a higher trust in the quality and reliability of a company and a doctoral degree can also open doors.

High university status entrepreneurs, such as postdoctoral fellows and professors, usually possess a high reputation. This makes it easier for them to gain legitimacy for a university spin-off. Yet these laurels in advance also oblige the academic entrepreneur to be more innovative and better than competitors, as this professor states: “The professorial image helped me a lot at the beginning, but of course it also commits me to always do more than my competitors. Of course I am expected to be a little more innovative, to perform a little bit better, have a bit better overview, and no standard concepts.” (USO68). These high expectations of customers rapidly lead to high pressures. Furthermore, high status academic entrepreneurs usually think twice before founding a university spin-off, because they are afraid of putting their career and reputation at risk. This fear can also hinder high status academic entrepreneurs to become an entrepreneur with a full commitment.

The majority of university spin-offs founded by high status academic entrepreneurs are listed in the sector “scientific services,” as mentioned before. This fact hinders the long-term growth of a company because the economic success of a university spin-off is strongly dependent on the academic entrepreneur’s university status and can hardly be transferred to other persons, as this quotation underlines: “The only risk, which is a problem in our private institute, is the moment where I would be absent. The company is quite dependent on my person, my name and the university context. Therefore, it is hardly possible to say that the company would continue to exist without me in case I retire. It is an important factor that I have to appear everywhere. Even if my staff knows it better than I do, the people expect me to be there. Much is dependent on my image and the whole concept. I think it will continue quite well as long as I am fit.” (USO68). This fact is a severe uncertainty factor for long-term university spin-off growth.

The results of the content analysis with a special focus on university status show that the reputation helps in terms of gaining legitimacy early on. This is especially useful at the beginning of the university spin-off but in the long run this can develop into a disadvantage because university spin-off growth is highly dependent on the academic entrepreneur’s university status. The hypothesis that especially high status entrepreneurs create high growth university spin-offs cannot be confirmed. Instead it is important to decouple the university spin-off from the academic entrepreneur and the university in the long run to achieve high growth (Rasmussen and Borch 2010).

4.2 Results from the Human Capital Perspective

In the following, I present the results concerning the second expectation that increasing human capital and resulting knowledge transfer may have a diminishing marginal utility for university spin-off growth and may even become disadvantageous. The focus is on human capital acquisition, firstly in terms of scientific expertise and the resulting knowledge transfer and secondly in terms of additional management skills acquired in a university.

Students and graduates, who discover a market gap and decide to exploit it, usually start up a university spin-off on the basis of the knowledge he or she acquired during studies. Transferring research results into practice plays a rather minor role at this low university status. Sometimes results of the diploma thesis or knowledge gained from the employment as a student assistant were implemented. However, in the majority of cases the identification of a market gap rather happened due to personal matters, social trends, experience and contacts from part-time jobs, internships or voluntary work. In these university spin-offs, only basic competencies acquired in studies are of importance.

Doctoral students, research associates (without a doctor’s degree), and doctors acquire profound scientific expertise in a certain subject during doctoral studies and research projects. The majority discover a market gap based on their research activities. Projects with high practical relevance and close contact to industry partners have the highest potential to be transferred into practice and facilitate a market entry. Many doctoral students, research associates and doctors start up a university spin-off because the industry partners have a concrete demand for a product developed in a research project. However, there are also a handful of doctoral students, research associates and doctors who set up a business only on the basis of basic competencies they acquired in their doctoral studies and research projects.

Postdoctoral fellows and professors possess extensive scientific expertise in different research areas, because they researched different projects for many years. The majority of them discovered a market gap due to their research and consultant activities. Industry contacts of course are also very helpful and facilitate a market entry.

Figure 3.3 shows the different characteristics of knowledge transfer and the number of university spin-offs for the respective university status. The results show that the higher the university status the more scientific expertise is acquired and therefore the more university knowledge is transferred to the university spin-off. With advancing university status the trend shifts from academic start-ups over competence spin-offs to exploitation spin-offs. However, a positive influence of the degree of university knowledge transfer into the university spin-off on spin-off growth could not be determined for our sample. Positive extreme cases exist for both, university spin-offs based on the exploitation of research results as well as university spin-offs based on the application of competencies. The majority of the university spin-offs of postdoctoral fellows and professors are listed in the scientific service sector. This often hinders the long-term growth because the tacit knowledge applied and the profound scientific expertise makes the company very dependent on the academic entrepreneur and can hardly be transferred to other persons.

Besides scientific expertise, academics also gain management skills in a university which might be helpful for entrepreneurship as the interviewees reported. The skills varied according to the university status. In the following some examples are given.

Students and graduates do not only possess little scientific expertise but also only little working experience which is mostly based on student projects, internships, part-time jobs, or diploma theses. Accordingly, they have only little experience in project management. In the early phase of a university spin-off, they may have difficulties to estimate and control the complexity, duration, and cost of customer orders. This often results in a high workload for them at certain times and in the worst case in a noncompliance with time limits. This can lead to order cancellations from customers and severe image damage. However, such initial problems are not serious in most cases, so that university spin-offs develop well, as this quotation of a student shows: “Of course we only had little experience. Nobody of us was professionally experienced and of course we did not have a clue about how to start a firm. Everything was quite improvised, but it still worked anyway.” (USO04). This quotation shows that youthful ease may help get over initial difficulties.

Doctoral students, research associates, and doctors have already acquired working experience in a university which is valuable for founding a university spin-off. Many of them already have experience in applying for, managing and evaluating research projects, as this quotation of a doctoral student shows: “Before, I made my living at the university with project applications, management, and evaluation. Actually, this is a skill, which I could bring to the company. I simply know where I have to look for support offers. I am able to overview that quite quickly.” (USO33).

Alongside the lower university status skills, postdoctoral fellows and professors are usually also responsible for personnel. Therefore, they attain valuable skills in personnel management as this postdoctoral fellow remarks: “Fortunately, as a group leader, I had to do personnel management, financial management and so on. I had a group of 15 people and I was fully responsible scientifically and financially.” (USO02).

These additional skills acquired in a university are certainly advantageous but they do not seem to be crucial for long-term university spin-off growth. The vast majority of the interviewees had to initially cope with a lack of business knowledge. I could not identify any long-term advantage for academic entrepreneurs who already had prior management knowledge.

4.3 Results from the Role Identity Perspective

In the following, I present the results concerning the third expectation that difficulties with role identity change may increase with advancing time in a university and hinder university spin-off growth. Therefore, I address the statements made by longstanding university staff that concern the difficulties in role identity change.

More than one quarter of our interviewees stated that they did not develop the desire to start a business until they had a concrete business idea. Before that, they either never thought about becoming an entrepreneur or they did not even want to become an entrepreneur (see Fig. 3.4). Especially for academic entrepreneurs with a high university status, the desire for entrepreneurship only developed with a concrete business idea quite late in their university career and oftentimes on demand from industry. This finding indicates that many academic entrepreneurs were not prepared emotionally and mentally for their new role, which can cause difficulties especially during the initial years.

For example, a professor reported that it was difficult for him to get used to the stress and workload that managing a university spin-off entails: “I have to say that being self-employed means greater stress than being employed at the university. I would almost say twice as much (laughing). Well, our applied projects are of course not as complex as basic research, but we handle eight, nine, ten projects at the same time. Particularly, they all have a certain time schedule that we have to meet. It generates a huge pressure to do everything as expected. As a professor, I have also worked a lot. But it is something else when you simply say: ‘That is a customer, who has to be served until a certain point. The results have to be presented and they have to be largely excellent.’ With a professorship it is something else. They don’t have the direct link of ‘When I lose a customer, I will have less money next year.’ For a professor this is completely different. Also the psychological pressure is not as high. If I screw something up as a professor, although nobody does it and nobody wants it and this harms my reputation, this does not affect my livelihood.” (USO68).

Another example for emerging difficulties due to different value systems between academia and the private sector is a lack of profit orientation. Individuals, who target a university career and already worked in university for long time, are usually not very profit oriented. They are rather driven by a scientific interest. This makes it difficult for them to run a university spin-off in the initial period. It takes them a while before they learn to change their viewpoint, as this professor vividly described: “You should not be too much of a geek and scientist who becomes obsessed with fiddling and loses sight of his targets. A crucial turning point for me was a banker who asked me right after starting the business: ‘Why have you started the business? What was your motivation?’ I had to think about what to answer, and things like self-fulfillment and having fun came to my mind. While I was thinking he said: ‘Now don’t start with self-fulfillment and it was so much fun. There is only one reason that you should have. Everything else doesn’t count; otherwise you can pack up and go home. The only right to exist for a business is to earn money.’ And he was right. It sounds so simple. In the beginning, it might also sound immoral, particularly if you tell this to a scientist. But he was right, I have to earn money. I have to evaluate everything I consider as a businessman; whether something comes out of it at the end of the day or whether it is only a little fun.” (USO41).

With regard to the commitment to the entrepreneurial role, the academic entrepreneurs in our study can be divided into two groups. On the one hand there are academic entrepreneurs who wanted to change their role and ended their university career for the university spin-off. On the other hand there are academic entrepreneurs who actually do not want to change roles and never leave the university. Around one third of the academic entrepreneurs in the sample decided to continue their university career and work in the university spin-off at the same time on a part-time basis (see Fig. 3.5). For some of these individuals the university career served solely to finance themselves in the initial years of business. However this career path can also be chosen because of opposite motives. For these individuals, the university career is the first choice. They never plan to be a full-time entrepreneur and leave university because they would rather do research and teaching. The question then is, why do these individuals startup a university spin-off in the first place. Individuals, who target a university career, see the university spin-off as a good opportunity either to finance their subsequent university career or to gain a reputation as a university professor later.

Many postdoctoral fellows in the sample decided to startup a university spin-off because they suffered from a lack of job security in the university due to part-time and fixed-term contracts. Usually postdoctoral fellows have almost no experience in the private sector but at the same time they are highly qualified and possess a mature personality. This makes it very difficult for them to find a subsequent job as a dependent employee in the private sector in case their contracts are not extended or they do not find a professorial chair after their habilitation. Therefore, they go on two separate tracks regarding their professional career. In the end, many of these kinds of academic entrepreneurs nevertheless stay in a university in the long run and their university spin-offs remain small for that reason. In contrast, the few postdoctoral fellows who left university immediately after foundation or after a transitional period have a good chance to establish big university spin-offs. Postdoctoral fellows who have discovered a market gap on the basis of their research projects and are disenchanted with the self-purpose of university research generally have a high growth potential because they are highly innovative and have a high commitment to their new role. However, a long development phase due to a low market maturity of the developed products or services often leads to high financing needs and delayed growth.

For the professors in the sample, the university career is definitely in first place and the university spin-off is of secondary importance. This lies in the nature of the chosen career paths. In engineering science professors usually start up a business because they can improve their reputation as well as research and teaching. Therefore, most professors do not start a university spin-off with a full commitment. More often professors are members of the founding team and support the university spin-off with scientific advice, financial capital, or reputation. Even if professors themselves generated the business idea they prefer to share the university spin-off with their employees, who then work with a full commitment, as this doctor reports about sharing the university spin-off with his professor: “We are three people in our company: Actually primarily me and the professor and another minority holder. I myself am actually responsible for the operating business, the rest is strategic advance, let’s just put it this way.” (USO48).

The results of the content analysis show that the role identity change from being a scientist to being an entrepreneur becomes increasingly difficult with longer working times in a university. Especially postdoctoral fellows and professors reported that they had trouble with this, whereas students and graduates who are at the beginning of their university careers, hardly ever described such problems. In contrast to management skills, the attitude towards entrepreneurship and adaption to a new value system are harder to learn. The socialization process, which takes place in a university, should therefore not be underestimated. As a result, with advancing time in a university and rising university status the commitment for an entrepreneurial role tends to decrease.

5 Results of Extreme Case Analysis

In this chapter I show the importance of and interaction between the three conceptual perspectives for selected cases. I identified three positive and three negative extreme cases in the samples in terms of university spin-off growth measured as the number of employees in 2011. I investigated their university career paths in depth in order to identify some patterns explaining the growth differences between high growth and low growth examples. They obviously vary considerably and it is clearly recognizable at a glance that a longer university career is not necessarily better for university spin-off growth (see Fig. 3.6).

Academic entrepreneurs’ career paths. Note: Results of the extreme case analysis. Growth is measured by the average annual increase in employees from the year of university spin-off formation to 2011. Sampling Approach based on positive and negative extreme cases. Source: Own illustration, USO survey 2011

In order to explain the importance of the willingness of role identity change, I compared the career paths of two academic entrepreneurs with the case numbers USO17 and USO34 (see Fig. 3.6). At first glance the interviewees have much in common. The two university spin-offs are founded in knowledge-intensive services and the academic entrepreneurs were still working at the university as professors at the time of the interview. They have both made prior experiences in the private sector, on the one hand through prior self-employment and on the other hand through dependent employment. They founded their second university spin-off after finishing the doctoral degree, which brought advantages for them at the beginning, as this quotation shows: “Of course my doctoral degree helped me solving practical problems like renting an office and convincing the landlord that I am absolutely able to pay the rent.” (USO17). Nevertheless the university spin-offs’ growth differs vastly. The academic entrepreneur of the high growth university spin-off left the university when founding his second university spin-off. The decision to leave the university was not quite voluntary. He transferred a research project into the university spin-off and founded the university spin-off and became a full-time entrepreneur, because he had no future at his parent university at that time: “When I founded the company, I actually quit the scientific career for myself.” (USO17). Later he describes of the fear of risking his career: “I was scared of how my life would continue. My parents were very concerned and very disappointed with my decision. I actually wanted to become a scientist and professor and they were scared that my career is ending now.” (USO17). After some years he established a large scientific service company and then decided to continue his university career and finish his habilitation after all. In contrast, the academic entrepreneur of the low growth university spin-off left the university after graduation, but after a short time in the private industry he realized that he wished to pursue a university career. Although he is shaped entrepreneurially by his family, he returned to the university. He founded the two university spin-offs because they forwarded his university career. He never had the intention to leave university to be a full-time entrepreneur, although the demand situation would allow an expansion. “If I do the controlling for large projects, I will get a lot of money, but this is rather craft work for me. That does not bring me forward as a professor. Consulting in large projects, the provision of expert opinions is what helps me professionally.” (USO34).

A similar situation applies to the academic entrepreneurs with the case numbers USO06 and USO63 (see Fig. 3.6). The interviewee of the high growth university spin-off continued his university career by making his Ph.D. for a few years after foundation in order to have a secure income during the initial years. “We decided that I remain at the university and my partner leads the company with full commitment, so that we try to ensure a certain seed funding. I received a regular salary at the university, while my self-employed partner did not earn any money at that time. Therefore, we said that we share my salary.” (USO06). This way, he was also able to gain deeper knowledge and to expand his industry contacts. For the academic entrepreneur of the low growth university spin-off the opposite is the case. He founded the university spin-off right after his graduation in order to finance his university career and never wanted to be a full-time entrepreneur, as this quotation illustrates: “I lead my company as a part-time job and get money for that. It is nothing different than acquiring third party funding, because I see myself as a scientist in the first place. I still write scientific studies.” (USO63). Obviously, the university spin-off is a means to an end for him. A university spin-off founded because of this reason will hardly become a big company. The data shows quite clearly that university spin-offs, which are not managed by at least one founding member with full commitment, at least for the initial years, usually stay small (see also Fig. 3.6).

In order to explain the interaction and evolving disadvantages from scientific expertise, deriving knowledge transfer and university status, I compared the academic entrepreneurs with the case numbers USO01 and USO46 (see Fig. 3.6). The interviewees have in common that they founded exploitation spin-offs in the service sector. During their research projects they both acquired a good reputation and established a wide social network not only within the scientific community but also to partners in the private economy and industry. USO01 was a reputable professor in engineering with many contacts to industry. He founded the university spin-off in the sector of scientific services on a concrete demand from one of his industry partners. He did it because he was a luminary in his field and he saw a possibility to finance his doctoral students by the university spin-off. The business was going well until he retired from university and the institute was closed. Even after many successful years on the market, the dependency of the university spin-off on the institute, the professor’s scientific expertise, and university status was still so high that the continuation of the business or the sale of the university spin-off to another professor was simply impossible. In contrast, the high growth academic entrepreneur USO46 acknowledged the danger of the dependence on university status and university. He founded the university spin-off after finishing his doctoral studies together with his professor in the consulting sector. At the beginning the professor’s reputation helped him a lot, but the decoupling of the university spin-off from the university and his professor’s reputation was very important for him. After some years on the market the professor retired progressively from the operative and even strategic business. The young doctor changed from the scientific role to the entrepreneurial role with full commitment. He managed the university spin-off on a full-time basis, and it has grown rapidly in its initial years. However, now the doctor received a call for a university chair. This will increase his reputation and financial situation. As a result, he plans to lead the university spin-off only on a part-time basis in future. Although he was aware of the importance to decouple the university spin-off from the parent university, he now plans to link it with his new university chair. He states that the employment increase will therefore most likely not exceed 15 employees, but he plans to raise outside funds.

The examples of the selected extreme cases show that a comprehensive consideration reveals the complex interaction between the three perspectives and thus allows further insights on how processes occur in reality. Although the academic entrepreneurs with a high university status state that they had advantages from the high reputation and their social network, these advantages are more important in the initial years. With advancing time on the market a high university status and profound scientific expertise even bears some risks for university spin-off growth. The decoupling of the university spin-off from the academic entrepreneur’s university status seems to be very important for long-term university spin-off growth in terms of employment increase. No less important is the identification with the entrepreneurial role and the willingness to manage the company with full commitment at least in the initial years.

6 Conclusions

Referring to the title of this paper it can be stated that a longer university career is not necessarily better for subsequent university spin-off growth. The theoretical assumptions as well as the empirical results from the content analysis and extreme case analysis show that each university status comprises certain advantages and disadvantages; summarized in Fig. 3.7. Academic entrepreneurs are located in a trade-off. With advancing university status the reputation and access to resources, the scientific expertise and resulting knowledge as well as the management competence of a person of course increases. Nevertheless, some examples show that a high degree of scientific expertise and the resulting knowledge transfer in connection with a high university status even develop into a disadvantage for long-term university growth due to a high dependency on the academic entrepreneur and on the university. Only for the role identity change the results are quite clear: With advancing university status, academic entrepreneurs have increased problems to change the roles and to lead the university spin-off with full commitment. Around one third of the academic entrepreneurs in the sample decided to continue their university career and work in the university spin-off at the same time on a part-time basis. These types of university spin-offs usually stay small (Nicolaou and Birley 2003; Doutriaux 1987). The willingness and ability for a role identity change in terms of commitment to the entrepreneurial role is very important for the growth intention of an academic entrepreneur and subsequent university spin-off growth. At least one founding member should work in the university spin-off with full commitment in the initial years. Overall, the results indicate that the cognitive ability and the social network of an academic entrepreneur are important to achieve university spin-off growth. However, the growth intentions also play a crucial role.

Advantages of university career for university spin-off growth. Note: Summarized results of the content analysis. Fading color of the triangle “Scientific Expertise and Resulting Knowledge Transfer” demonstrates diminishing marginal utility. In principle, missing advantages may be counted as disadvantages, but each advantage may also entail a respective disadvantage as explained in the text. Source: Own illustration, USO survey 2011

6.1 Research Implications

The study contributes to a better understanding of the career paths of academic entrepreneurs and the effects on university spin-off performance by using three different research perspectives: human capital (Becker 1975; Lazear 2005), university status (Phillips and Zuckerman 2001), and role identity (Jain et al. 2009; Merton 1973). The current study thereby also contributes to the existing literature on university spin-off development and performance because, in contrast to the existing literature, it considers the time at university as being important for the subsequent university spin-off performance.

Examining career paths is quite a complex task. They extend over a long period of time and include decisions which are path dependent and interrelated (Kodithuwakku and Rosa 2002; Druilhe and Garnsey 2004). The relationship between the career paths of entrepreneurs and growth intentions is therefore still ambiguous. While some quantitative studies deny an influence (Kolvereid 1992; Birley and Westhead 1994) others empirically prove it (Cassar 2007). The qualitative research design has thereby proven to be a great advantage for analyzing the career paths of academic entrepreneurs.

The results of this study show that the role identity change and the resulting growth intention of an academic entrepreneur have a crucial influence on university spin-off growth. Although some empirical studies in the recent past have suggested that entrepreneurial growth intentions are important for subsequent business growth (Gundry and Welsch 2001; Cassar 2007; Hermans et al. 2012; Stam et al. 2007; van Stel et al. 2010; Douglas 2013), this issue has hardly been considered in the field of academic entrepreneurship. Further research should therefore consider growth intentions as being important for university spin-off growth and investigate this relationship more in depth.

The results of this study furthermore show that only a minority of university spin-offs belongs to the group of high flyers and many lead a university spin-off on a part-time basis. Further research should therefore look at self-employment as a part-time job for scientists. This phenomenon has only received little attention in literature so far (Nicolaou and Birley 2003; Jain et al. 2009), although it might represent an untapped potential for the university and the region. Also, it should be investigated what kind of alternative benefits, apart from employment and profit, derive from university spin-offs once for the region and once for the university. Especially in the German context, this is of particular importance because German universities usually are not allowed to acquire shares in the university spin-offs and do not receive any financial benefit.

6.2 Policy Implications

On the basis of the results, the policy recommendation is that subsidies should not be dependent on a high degree of knowledge transfer or a high university status of the academic entrepreneur. Instead, it is of particular importance to consider the university status and career plans of an academic entrepreneur, in order to compensate particular disadvantages of different university statuses and to recognize an academic entrepreneur’s growth intention. Furthermore, I recommend, to support, the formation of founding teams with complementary skills and university statuses (Breitenecker et al. 2011; Ensley and Hmieleski 2005). Students and doctoral students usually have a high willingness to learn. This might diminish the cognitive distance between professors and management graduates (Nooteboom et al. 2007). The professor’s scientific expertise would be coupled with the students’ risk disposition and flexibility. The graduates therefore could profit from the professor’s reputation and far-reaching social networks. Nevertheless some problems might occur. Disputes can arise due to an imbalance between the professor and the students. Due to the different university statuses, collaboration at eye-level is difficult. A possible solution to avoid many problems in advance is to clarify the division of tasks and competence fields from the beginning. This empirical study describes some positive examples where professors are shareholders and scientific advisors, but the operating business is performed by graduates, so that both sides can benefit from each other.

6.3 Limitations

Although the present empirical study fills certain research gaps, one needs to consider the results in the context of limitations, which I address in the following. Firstly, limitations regarding the transferability of the results should be considered. The results are solely based on a sample within the German context, whereas both universities are located in the same federal state with comparable environments. Despite several reasons justifying this approach, it should be noted that the results are therefore hardly transferable to other regions or countries.

Secondly, the following data-related biases should be considered. The study is largely based on established university spin-offs. I only contacted those academic entrepreneurs who were still on the market at the time of the survey, although a large number of academic entrepreneurs do not succeed in establishing and running a university spin-off (Garnsey 1998). Furthermore, I only took private limited companies and corporations into account. Thus, a general success bias might exist. One could also assume some bias due to nonresponse. However, those academic entrepreneurs who did not respond to our contact request, could be either less or more successful. Some may be embarrassed, others could be too busy. I interviewed academic entrepreneurs ex-post. A retrospective study always tends to suffer from some kind of memory decay. There is a risk that outcomes are assigned to circumstances that did not in fact exist at that time.

Finally, the qualitative content analysis is only focused on the differences of university statuses and their influence on university spin-off growth. Nevertheless advantages and disadvantages exist, which many of our interviewees had in common: Generally all the university spin-offs in our sample are knowledge-intensive. A relatively high amount of human capital can be assumed for all academic entrepreneurs in our sample. Independently from the university status, some academic entrepreneurs in the sample had prior entrepreneurial experience and therefore huge advantages. However, the vast majority of the interviewees had to cope with a lack of business knowledge. Because of the novelty of the products and services it was difficult to estimate market potential and costumer demand. Many of our sampled entrepreneurs had problems in entering the market.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

These are the MINT subjects (mathematics, computer science, natural science and engineering) and medical science (Kulicke et al. 2008). MINT subjects are comparable with the STEM fields used in English that comprise science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

- 3.

See acknowledgements at the end of this chapter.

- 4.

Although the cases were also equally distributed between the two chosen universities, I did not differentiate the academic entrepreneurs according to their parent university in this study, because this was only relevant for the research project. For the aim of this present study the parent university was not relevant.

- 5.

A few academic entrepreneurs were interviewed at neutral places or by telephone due to distance, space or scheduling problems.

- 6.

In a few cases a content protocol was written during the interview if the interviewee did not want to be recorded.

- 7.

Qualification phase after the doctorate for a teaching career in higher education.

- 8.

Firm’s performance can be measured in many different ways. Common indicators used in literature are survival rate, employment growth, sales growth, productivity and credit rating (Helm and Mauroner 2011). This paper focuses on employment as a measure of performance because it has the most consistent positive correlation with other growth measures and is a key interest among policy makers (Wiklund 1998; Davidsson et al. 2007). Furthermore, it is less susceptible to fluctuations and a good indicator for the university spin-offs’ overall assets (Gibcus and Stam 2012). Nevertheless, these propositions do not apply to all branches equally. Other definitions of university spin-off growth could lead to different results. Furthermore, university spin-off growth should not be equated with success, because success always depends on the respective business goals (Hayter 2010).

References

Baker SE, Edwards R (2012) How many qualitative interviews is enough. National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/4/how_many_interviews.pdf

Bathelt H, Kogler DF, Munro AK (2010) A knowledge-based typology of university spin-offs in the context of regional economic development. Technovation 30(9–10):519–532

Becker GS (1975) Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Columbia University Press, New York

Bernard HR, Ryan GW (2009) Analyzing qualitative data: systematic approaches. Sage, Los Angeles

Birley S, Westhead P (1994) A taxonomy of business start-up reasons and their impact on firm growth and size. J Bus Ventur 9(1):7–31

Braun-Thürmann H, Knie A, Simon D (2010) Unternehmen Wissenschaft—Ausgründungen als Grenzüberschreitungen akademischer Forschung [Enterprise science—spin-offs as bordercrossings of academic research]. Transcript, Bielefeld

Breitenecker RJ, Schwarz EJ, Claussen J (2011) The influence of team heterogeneity on team processes of multi-person ventures: an empirical analysis of highly innovative academic start-ups. Int J Entrep Small Bus 12(4):413–428

Cassar G (2007) Money, money, money? A longitudinal investigation of entrepreneur career reasons, growth preferences and achieved growth. Entrep Reg Dev 19(1):89–107

Chandler GN, Jansen E (1992) The founder’s self-assessed competence and venture performance. J Bus Ventur 7(3):223–236

Cohen WM, Klepper S (1992) The tradeoff between firm size and diversity in the pursuit of technological progress. Small Bus Econ 4(1):1–14

Colombo MG, Grilli L (2005) Founders’ human capital and the growth of new technology-based firms: a competence-based view. Res Policy 34(6):795–816

Czarnitzki D, Rammer C, Toole A (2014) University spin-offs and the “performance premium”. Small Bus Econ 43(2):309–326

Davidsson P, Honig B (2003) The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. J Bus Ventur 18(3):301–331

Davidsson P, Achtenhagen L, Naldi L (2007) What do we know about small firm growth? In: Parker S (ed) The life cycle of entrepreneurial ventures, vol 3. Springer, New York, pp 361–398

Ding W, Choi E (2011) Divergent paths to commercial science: a comparison of scientists’ founding and advising activities. Res Policy 40(1):69–80. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2010.09.011

Dörre K, Neis M (2010) Das Dilemma der unternehmerischen Universität: Hochschulen zwischen Wissensproduktion und Marktzwang [The dilemma of the entrepreneurial university: universities between knowledge production and market pressure]. Edition Sigma, Berlin

Douglas EJ (2013) Reconstructing entrepreneurial intentions to identify predisposition for growth. J Bus Ventur 28(5):633–651

Doutriaux J (1987) Growth pattern of academic entrepreneurial firms. J Bus Ventur 2(4):285–297, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(87)90022-X

Druilhe C, Garnsey E (2004) Do academic spin-outs differ and does it matter? J Technol Transf 29(3):269–285

Egeln J, Gottschalk S, Rammer C, Spielkamp A (2002) Spinoff-Gründungen aus der öffentlichen Forschung in Deutschland: Kurzfassung; Gutachten für das Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung [Spin-offs from public research in Germany: summary; report for the Federal Ministry for Education and Research]. ZEW Dokumentationen

Ensley MD, Hmieleski KM (2005) A comparative study of new venture top management team composition, dynamics and performance between university-based and independent start-ups. Res Policy 34(7):1091–1105

Erdös K, Varga A (2012) The academic entrepreneur: myth or reality for increased regional growth in Europe? In: Erdös K, Varga A (eds) Creative knowledge cities: myths, visions and realities. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 157–181

Etzkowitz H (2008) The triple helix. University-industry-government. Innovation in action. Routledge, Madison

Federal Bureau of Statistics (2013) Kleine und mittlere Unternehmen (KMU) [Small and medium enterprises (SME)]. https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesamtwirtschaftUmwelt/UnternehmenHandwerk/KleineMittlereUnternehmenMittelstand/KMUBegriffserlaeuterung.html. Accessed 1 May 2013

Garnsey E (1998) A theory of the early growth of the firm. Ind Corp Chang 7(3):523–556

Georg-August-Universität Göttingen (2013) Zahlen, Daten und Fakten [Numbers, data and facts]. http://www.uni-goettingen.de/de/24499.html. Accessed 31 Oct 2013

Gibcus P, Stam E (2012) Firm resources, dynamic capabilities, and the early growth of firms. Scales research reports, EIM Business and Policy Research, H201219

Gläser J, Laudel G (2009) Experteninterviews und qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Als Instrumente rekonstruierender Untersuchungen [Expert interviews and qualitative content analysis: as instruments of reconstructing investigations]. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden

Gundry LK, Welsch HP (2001) The ambitious entrepreneur: high growth strategies of women-owned enterprises. J Bus Ventur 16(5):453–470

Hayter C (2010) In search of the profit-maximizing actor: motivations and definitions of success from nascent academic entrepreneurs. J Technol Transf 36(3):340–352

Helm R, Mauroner O (2007) Success of research-based spin-offs. State-of-the-art and guidelines for further research. Rev Manag Sci 1(3):237–270

Helm R, Mauroner O (2011) Soft starters, research boutiques and product-oriented firms: different business models for spin-off companies. Int J Entrep Small Bus 12(4):479–498

Hermans J, Vanderstraeten J, Dejardina M, Ramdani D, Stam E, van Witteloostuijn A (2012) Ambitious entrepreneurship: antecedents and consequences. Department of Economics Working Papers Series 1210, University of Namur, Namur

Jain S, George G, Maltarich M (2009) Academics or entrepreneurs? Investigating role identity modification of university scientists involved in commercialization activity. Res Policy 38(6):922–935. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2009.02.007

Karnani F, Schulte R (2010) Screening von Gründungspotenzialen—Kompetenz-Ausgründungen aus Hochschulen und Forschungseinrichtungen: Oder: Wie man Innovationspotenziale kartographiert. [Screening entrepreneurial potentials—competence spin-offs from universities and research institutions: or how one can map innovation potentials]. Lüneburger Beiträge zur Gründungsforschung, 7

Klofsten M, Jones-Evans D (2000) Comparing academic entrepreneurship in Europe—the case of Sweden and Ireland. Small Bus Econ 14(4):299–309

Kodithuwakku SS, Rosa P (2002) The entrepreneurial process and economic success in a constrained environment. J Bus Ventur 17(5):431–465

Kolvereid L (1992) Growth aspirations among Norwegian entrepreneurs. J Bus Ventur 7(3):209–222

Kulicke M, Schleinkofer M, Mallig N, Schönenbrücher J, Heiser C (2008) Rahmenbedingungen und Potenziale für Ausgründungen aus der Wissenschaft, Aktueller Stand im Kontext von EXIST–Existenzgründungen aus der Wissenschaft [Framework conditions and potentials for spin-offs from the science, current status in the context of EXIST business start-ups from the science]. Fraunhofer IRB, Stuttgart

Lawton Smith H (2007) Universities, innovation, and territorial development: a review of the evidence. Environ Plann C Govern Pol 25(1):98–114

Lawton Smith H, Ho K (2006) Measuring the performance of Oxford University, Oxford Brookes University and the government laboratories’ spin-off companies. Res Policy 35(10):1554–1568

Lazear EP (2005) Entrepreneurship. J Labor Econ 23(4):649–680

Leibniz Universität Hannover (2013) Studierendenstatistik Sommersemester 2013 [Statisticso on students summer semester 2013]. http://www.uni-hannover.de/imperia/md/content/strat_controlling/statistiken/allgemein/sommersemester_2013.pdf. Accessed 31 Oct 2013

Mangematin V (2000) PhD job market: professional trajectories and incentives during the PhD. Res Policy 29(6):741–756

Mason C, Tagg S, Carter S (2011) Does education matter? The characteristics and performance of business started by recent university graduates. In: Borch OJ, Fayolle A, Kyro P, Ljunggren E (eds) Entrepreneurship research in Europe: evolving concepts and processes, European research in entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 13–33

Mayring P (2008) Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken [Qualitative content analysis: basics and techniques]. Beltz, Weinheim

Merton RK (1973) The sociology of science. Theoretical and empirical investigations. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Miles MB, Huberman AM (1994) Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Müller B (2006) Human capital and successful academic spin-off. ZEW discussion paper

Murray KB, Häubl G (2007) Explaining cognitive lock-in: the role of skill-based habits of use in consumer choice. J Consum Res 34(1):77–88

Mustar P, Wright M, Clarysse B (2008) University spin-off firms: lessons from ten years of experience in Europe. Sci Public Policy 35(2):67–80

Nicolaou N, Birley S (2003) Academic networks in a trichotomous categorisation of university spinouts. J Bus Ventur 18(3):333–359

Nooteboom B, Van Haverbeke W, Duysters G, Gilsing V, van den Oord A (2007) Optimal cognitive distance and absorptive capacity. Res Policy 36(7):1016–1034

Nörr M (2010) Spin-Offs: Wie Wissenschaftler zu Unternehmern werden. Anforderungen an den Gründer und das Transferobjekt [How scientists become entrepreneurs. Requirements on the founder and the transfer object]. Diplomica, Hamburg

Parker SC (2005) The economics of entrepreneurship: what we know and what we don’t. Now Publishers, Boston

Phillips DJ, Zuckerman EW (2001) Middle-status conformity: theoretical restatement and empirical demonstration in two markets. Am J Sociol 107(2):379–429

Pirnay F, Surlemont B, Nlemvo F (2003) Toward a typology of university spin-offs. Small Bus Econ 21(4):355–369

Rappert B, Webster A, Charles D (1999) Making sense of diversity and reluctance: academic-industrial relations and intellectual property. Res Policy 28(8):873–890

Rasmussen E (2011) Understanding academic entrepreneurship: exploring the emergence of university spin-off ventures using process theories. Int Small Bus J 29(5):448–471. doi:10.1177/0266242610385395

Rasmussen E, Borch OJ (2010) University capabilities in facilitating entrepreneurship: a longitudinal study of spin-off ventures at mid-range universities. Res Policy 39(5):602–612. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2010.02.002

Roberts EB, Malone DE (1996) Policies and structures for spinning off new companies from research and development organizations. R D Manag 26(1):17–48

Saxenian A (1983) The genesis of Silicon Valley. Built Environ 9:7–17

Schreier M, Naderer G, Balzer E (2007) Qualitative Stichprobenkonzepte [Qualitative sampling concept]. In: Naderer G, Balzer E (eds) Qualitative Marktforschung in Theorie und Praxis. Gabler, Wiesbaden, pp 231–245

Shane S (2004) Academic entrepreneurship: university spinoffs and wealth creation (New Horizons in Entrepreneurship). Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Smilor RW, Gibson DV, Dietrich GB (1990) University spin-out companies: technology start-ups from UT-Austin. J Bus Ventur 5(1):63–76

Stam E, Suddle K, Jolanda SJA, Andre van Stel A (2007) High growth entrepreneurs, public policies and economic growth. Jena Economic Research Papers, 2007(019)

Stephan P, Levin S (1996) Property rights and entrepreneurship in science. Small Bus Econ 8(3):177–188

Sternberg R (1995) Technologiepolitik und High-Tech Regionen: Ein internationaler Vergleich [Technology policy and high-tech regions: an international comparison]. LIT, Münster

Stützer M (2010) Human capital and social capital in the entrepreneurial process. Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Fakultät, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Jena

Szyperski N, Klandt H (1981) Wissenschaftlich-technische Mitarbeiter von Forschungs- und Entwicklungseinrichtungen als potentielle Spin-off-Gründer. Eine empirische Studie zu den Entstehungsfaktoren von innovativen Unternehmungsgründungen im Lande Nordrhein-Westfalen. [Scientific-technical staff of research and development institution as potential spin-off founders. An empirical study on the factors of development of innovative start-ups in the Land of North Rhine-Westphalia]. Westdeutscher, Opladen

van Stel A, Thurik R, Stam E, Hartog C (2010) Ambitious entrepreneurship, high-growth firms and macroeconomic growth. Scales Research Reports, EIM Business and Policy Research, H200911

Vohora A, Wright M, Lockett A (2004) Critical junctures in the development of university high-tech spinout companies. Res Policy 33(1):147–175

Wennberg K, Wiklund J, Wright M (2011) The effectiveness of university knowledge spillovers: performance differences between university spinoffs and corporate spinoffs. Res Policy 2011(40):1128–1143

Wentland A, Knie A, Simon D (2011) Warum aus Forschern keine Erfinder werden: Innovationshemmnisse im deutschen Wissenschaftssystem am Beispiel der Biotechnologie [Why scientists do not become inventors: innovation barriers in the German science system, the example of the biotechnology sector]. WZBrief Bildung, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, 17

Wiklund J (1998) Small firm growth and performance: entrepreneurship and beyond. Internationella Handelshögskolan, Jönköping

Zhang J (2009) The performance of university spin-offs: an exploratory analysis using venture capital data. J Technol Transf 34(3):255–285

Acknowledgments