Abstract

Despite the growing interest in academic entrepreneurs’ role conflict, we have not gained sufficient insights into its antecedents. Based on social learning theory, we examine how academic entrepreneurs’ prior experience—prior academic experience and prior entrepreneurial experience—influence their role conflict. Through multilevel linear regression and robustness tests using data from 394 academic entrepreneurs, we show that prior academic experience positively impacts role conflict, while prior entrepreneurial experience negatively impacts role conflict. Moreover, the negative effect of academic experience is weaker for academic entrepreneurs who have a longer length of prior entrepreneurial experience. Our study contributes to the literature on the antecedents of academic entrepreneurs’ role conflict and has important practical implications for academic entrepreneurial project cultivation and selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The past decade has witnessed a remarkable new value of scholars acting as initial “knowledge-entrepreneurship” agents in the commercialization of the professional knowledge generated in universities instead of just the value of the publication and dissemination of academic findings (Hayter, 2015; Hayter et al., 2017; Méndez-Picazo et al., 2021). Therefore, researchers have recently shown an increasing interest in academic entrepreneurship issues (Balven et al., 2018; Bartunek & Rynes, 2014; Hayter et al., 2017; Jain et al., 2009; Zou et al., 2019). Academic entrepreneurs are defined as scholars who launch an entrepreneurial project and work in academic departments where the knowledge is created (Abreu & Grinevich, 2013). Accordingly, academic entrepreneurs wear two “hats”, namely, a scholar role identity and an entrepreneur role identity (Bo et al., 2019; Zou et al., 2019).

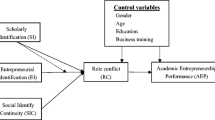

As academic and entrepreneurial role identity varies in logic (universalism vs. uniqueness), time horizons (long-term vs. short-term), and interest (papers vs. product), researchers are devoted to exploring the role conflict of academic entrepreneurship (Jain et al., 2009; Li et al., 2020; Meek & Wood, 2016; Rosenlund & Legrand, 2021; Shibayama, 2012; Zou et al., 2019). For example, Jain et al. (2009) proposed that the scholar identity-entrepreneur identity varies in role rules and that, consequently, academic entrepreneurs adopt two strategies, namely, delegating and buffering, to manage their hybrid identity. Zou et al. (2019) proposed that scholarly identification, entrepreneurial identification, and social identity continuity are important antecedents of role conflict. These studies have provided useful insight into the antecedents, forms and coping strategies of role conflict, and the focus of most of these studies has been role conflict that occurs at the microcognitive level. However, role conflicts also refer to conflicting time arrangements and role behavior patterns between academia and entrepreneurship that are incompatible in ways such that participation in one role is made more difficult by virtue of participation in the other. The degree of conflicts that occur at the behavioral level is closely related to domain-specific knowledge and skills. According to social learning theory, prior experience makes a critical contribution to cultivating domain-specific knowledge and skills (Bandura, 1977; Kolb, 1984). However, the important role of prior experience in role conflict remains unexplored, especially the impact of two very different experiences—scholarly experience and entrepreneurial experience—on academic entrepreneurs.

Existing studies have shown that entrepreneurial experience positively contributes to commercial thinking, opportunity evaluation skills and entrepreneurial motivation (Clarysse et al., 2011; Jenkins et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2019; Toft-Kehler et al., 2014; Ucbasaran et al., 2010; Zhan et al., 2020), while scholarly experience positively contributes to critical thinking and publishing skills (Pascarella et al., 2014). In the early stage of scholars’ leap into the business world, academic entrepreneurs already possess a well-developed scholarly behavior pattern but lack the knowledge and execution skills related to entrepreneurship (Jain et al., 2009). In this scenario, entrepreneurs may not be able to handle dual inconsistent roles with ease and thus feel role conflicts. Based on this, we predict that by endowing academic entrepreneurs with domain-specific knowledge and beliefs, both scholarly and entrepreneurial experience will have an important impact on role conflict. As such, we focus on and distinguish those two types of prior experience and theorize that these experiences have opposite effects on role conflict. Specifically, we theorize that prior entrepreneurial experience elevates academic entrepreneurs’ entrepreneurial competency and decreases the degree of role conflict by reducing their role overload and promoting their ability to control dual works. In contrast, we theorize that prior scholarly experience elevates academic entrepreneurs’ academic competency and increases the degree of role conflict by solidifying their academic cognitive schemas (knowledge, beliefs, and memories) and increasing their role pressure. We further predict that the two types of experiences have an interaction effect such that the positive effect of academic experience on role conflict is weaker when academic entrepreneurs have more academic experience. Using questionnaire survey data from 294 academic entrepreneurs, the empirical results support our theoretical hypothesis.

Our study has several theoretical contributions and practical implications. First, we enrich the research on the antecedents of academic entrepreneurs’ role conflict by introducing an important yet understudied microlevel factor—prior experiences—and further advance the understanding of why some academic entrepreneurs perceive more role conflict than others. Second, we contribute to prior experience research in the field of entrepreneurship by finding that prior academic experience and prior entrepreneurial experience have opposite effects on academic entrepreneurs’ role conflict. Third, we contribute to the literature on the link between social learning theory and academic entrepreneurship by investigating the impact of prior experience on academic entrepreneurs’ role conflict.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. First, our fundamental theories are introduced. Second, a hypothesis model including academic experience, entrepreneurial experience and role conflict is developed. Then, methodology and empirical findings, including data collection, measurement, data analysis, and follow-up results, are presented. Finally, both theoretical and practical discussions of the findings are offered.

Theoretical background

Role conflict theory

A role is defined as “a particular set of norms that is organized about a function (Biddle, 1986).” Roles bring specific expectations for values and beliefs, which in turn drive individuals’ interactive behaviors in different social contexts (Stets & Burke, 2000). Individuals need to assume markedly different roles in various social contexts and further transfer with great frequency between those various roles over time in their daily life (Ashforth et al., 2001). Role conflicts occur when those roles put forward substantially different requirements in regard to physical, temporal, emotional and obligatory values (Balven et al., 2018; Rizzo et al., 1970). Those inconsistent values between conflicting roles will lead to cognitive dissonance, which increases the psychological and physical costs (e.g., emotional, time, cognitive and space cost) of role management (Ashforth, 2000).

Academic entrepreneurs are typically defined as academic scientists who are involved in the processes of opportunity pursuit and technology transfer. They typically have hybrid roles, that is, both scholarly roles and commercial personas (Bartunek & Rynes, 2014). Existing research has shown that these two roles vary in many realms, such as value, time, interests and motivations (Bartunek & Rynes, 2014; Jain et al., 2009). Specifically, entrepreneurs pay more attention to short-term goals, mercantilism and currency profits. Academic orientation typically claims to focus more on long-term goals, rigidity and peer recognition (Jain et al., 2009). Obviously, rigidity contributes to the research work of scholars, and it might not be inappropriate for entrepreneurs, as they must be flexible and commercial enough to cope with the dynamic business environment. Accordingly, during the process of academic entrepreneurship, role conflict has become the most common problem faced by academic entrepreneurs.

Social learning theory

Learning theory is widely used to explain the outcomes of various prior experiences (e.g., Kolb, 1984; Li et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2020). Social learning theory indicates that learning occurs when individuals are involved in new experiences that are different from their existing knowledge or beliefs (Bandura, 1977). Those differences between the individuals and their engaged environment motivate learning processes (Fee et al., 2013). Through this learning process, individuals can gain greater professional knowledge pertaining to both specific fields and general knowledge (Piaget, 1954). This new knowledge is applied in addition to sophisticated existing cognitive schemas (knowledge, beliefs, and memories) (Endicott et al., 2003), which play an important foundational role in the changes of individuals’ competencies, interests and even their views of the value of their work.

Experience in both academic and entrepreneurial activities can bring individuals into somewhat of a new breadth or depth from the context of their existing knowledge and thus stimulate their learning process. With regard to academic experience, individuals can gain greater domain-specific knowledge that is aligned with academic norms, such as maintaining skepticism and focusing on peer recognition and writing skills. Similarly, entrepreneurial experiences can bring about greater professional knowledge that is in line with commercial logic, such as maintaining optimism and focusing on profits and management skills (Bartunek & Rynes, 2014; Jain et al., 2009). In addition to role domain-specific knowledge, individuals with both academic and entrepreneurial experience can also gain knowledge about role management from the learning process. The incompatibility norms and values of scholars and entrepreneurs cause these two roles to be often viewed as the opposite of one another (Jain et al., 2009), which provides stimuli that create dissonance in cognitive schemas (Bandura, 1977). The resulting dissonance leads to a sense of anxiety and discomfort and thus heightens learning, which brings about more role management strategies to diminish dissonance and discomfort (Festinger, 1957). In the section on hypothesis derivation, we apply the learning theory insights mentioned above to explore how academic and entrepreneurial experiences affect role conflicts.

Hypotheses

Prior academic experience and role conflict.

We argue that prior scholarly experience may increase role conflict. First, drawing on social learning theory, prior academic experience provides a stimulus to learn professional academic knowledge by doing, which strengthens individuals’ tendency to act according to academic archetypes, such as critical thinking (Pascarella et al., 2014). However, scholars' conduct norms are inconsistent with society's expectations of the entrepreneur role (Jain et al., 2009). For academic entrepreneurs, we argue that scholars' cognitive schemas and the behavior norms reinforced by academic experience debilitate their flexibility to transition between scholars and entrepreneurs, thus leading to role conflicts.

Second, for most scholars engaged in academic activities, being an academic entrepreneur means that he or she is required to adjust their role arrangement to distribute a certain amount of time and energy to entrepreneurs' activities, especially in the first three years of entrepreneurship (Zou et al., 2019). Academic entrepreneurs thus assume a higher workload from the two slightly inconsistent roles in their daily life (Bartunek & Rynes, 2014; Clarke & Holt, 2017). We argue that academic entrepreneurs with longer prior academic experience are more likely to experience role pressure from role overload, as the cognitive norms and behavior patterns shaped by their scholarly role’s domain are more likely to overflow into the entrepreneurial role, thereby causing them to be physically located in the entrepreneurial role's domain but psychologically and/or behaviorally involved in the scholarly role. Under the guidance of such inconsistent role expectations, academic entrepreneurs may feel disordered when dealing with entrepreneurial activities, thus arising role conflicts.

H1: Academic entrepreneurs with longer prior academic experience will be positively associated with role conflict.

Prior entrepreneurial experience and role conflict.

In contrast, we argue that prior entrepreneurial experience may reduce role conflict. First, according to social learning theory, prior entrepreneurial experience enables individuals to enlarge their tacit knowledge and skills related to entrepreneurial activities, such as opportunity pursing, financing seeking, market development, and customer management (Toft-Kehler et al., 2014; Olugbola, 2017). The entrepreneurial domain knowledge improves his or her competitiveness in building their business advantages (Dimov, 2010). For academic entrepreneurs, we argue that this kind of entrepreneurial competence brought about by entrepreneurial experience allows them to perform better in their entrepreneurship and reduces the role overload caused by the dual roles, which consequently alleviates role conflict.

Second, many studies have found that prior experience is closely related to psychological commitment. For example, Zhu et al. (2020) indicated that prior board experience at other firms can weaken individuals’ psychological commitment to the current strategy, thereby increasing the possibility of initiating strategic changes. Consistent with this proposition, we argue that prior academic experience contributes to weakening individuals’ strong psychological commitment to their scholarly role and accepting entrepreneurship as their new role, which is helpful for strengthening their sense of academic and entrepreneurial control and consequently alleviating role conflict. Thus, academic entrepreneurs’ entrepreneurial experience may have a positive impact on reducing role conflict.

H2: Academic entrepreneurs with longer prior entrepreneurial experience will be negatively associated with role conflict.

Moderating role of entrepreneurial experience.

We expect that entrepreneurial experience can play a moderating role in the relationship between academic experience and role conflict; that is, scholarly and entrepreneurial experience can interact to influence scholar-entrepreneur role conflict.

When academic entrepreneurs have a longer duration of entrepreneurial experience, they are heavily involved in the development of the startups, which makes them more equipped with entrepreneurial domain knowledge and more psychologically adaptable to the entrepreneur role. In this situation, the negative effect of academic experience on role conflict will be weakened because these academic entrepreneurs are more skilled in dealing with entrepreneurial problems and less constrained by their prior academic norms and thus are likely to be more flexible in spatial and temporal arrangements while encountering different demands from both roles simultaneously (Zhu et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2019). The more prior entrepreneurial experience academic entrepreneurs have, the weaker the negative impact of academic experience on role conflicts will be.

In contrast, when academic entrepreneurs have a shorter duration of entrepreneurial experience, they are likely to be equipped with entrepreneurial knowledge and have a high level of commitment to their scholar identity because of their lower level of involvement in entrepreneurial activities before becoming academic entrepreneurs. The positive impact of academic experience on role conflict is likely to be amplified for academic entrepreneurs who have little prior entrepreneurial experience because their lack of involvement in business issues makes their behavior pattern less aligned with the expectations of entrepreneurial roles but strongly shaped by academic norms (Bartunek & Rynes, 2014; Kolb, 1984). This results in academic entrepreneurs being less pliable to meet different demands from dual roles. Therefore, the less prior entrepreneurial experience academic entrepreneurs have, the stronger the negative impact of academic experience on role conflicts will be.

Taken together, academic entrepreneurs’ academic experience has a stronger (weaker) effect on enhancing academic conduct norms and increasing the degree of role conflict when they have less (more) entrepreneurial experience.

H3: The positive relationship between prior academic experience and role conflict is stronger when individuals have less academic experience.

Thus, We plot our theoretical model in Fig. 1.

Sample and method.

Sample and data source

To test our theoretical model, we chose to study the academic works in colleges or research institutions of individuals who are also engaged in entrepreneurship-related activities, such as launching entrepreneurial projects, providing technical or management consulting, and participating in commercial cooperative R&D projects. The final sample consisted of 394 academic entrepreneurs from five provinces around China, namely, Jiangsu, Anhui, Shandong, Shanxi, and Guangdong, which have great differences and representativeness in terms of geographical location, number of academic institutions and economic development level.

According to Gielnik et al. (2015), we contacted potential participants in multiple ways, including personal networks, university pioneer parks, and email addresses published on the official website, to obtain a range of different academic entrepreneurs. During the half-year survey, we contacted 1052 potential participants through field visits (294/1052) and emails (758/1052) and asked their intention to participate after explaining the purpose of the survey. In addition to those who directly refused to participate and failed to respond on time, we received 768 questionnaires. According to the answers to the screening question, 462 participants met the two requirements for academic entrepreneurship identity, that is, doing academic-related work and participating in entrepreneurial projects, which contained three different types of academic entrepreneurs: 1) entrepreneurs working in universities; 2) entrepreneurs working in scientific research institutes; and 3) graduate students and doctoral students participating in entrepreneurship projects.

Due to the scarcity of academic entrepreneurs, to maximize the use of data, we retained data with a maximum of three missing values from different items.Footnote 1 Based on this, we excluded invalid questionnaires with seriously missing data or the same answer for all questions, and a total of 394 valid respondents were obtained. Among those academic entrepreneurs, 61.68% were male, and 62.94% were between 35 and 55 years old. In terms of education, the majority (97.21%) had completed a bachelor's degree, 36.04% had completed a master's degree, and 41.37% had completed a Ph.D. In terms of professional title, 43.40% of the respondents were lecturers, and 41.37% of the respondents had obtained the title of associate professor or professor. Before engaging in current entrepreneurial experience, the respondents had an average prior academic experience of 56 months and an average entrepreneurial experience of 7 months. The average age of their current entrepreneurial project was 2.67 years, and these projects are scattered in various industries, such as manufacturing, retail, services (such as finance, investment, consulting), biotechnology and software.

Empirical model

Based on Hypotheses 1, 2 and 3, prior academic experience was defined as an independent variable. Prior entrepreneurial experience was defined as both an independent variable and moderator. Role conflict was considered as dependent variable. A series of control variables that account for influencing role conflict and entrepreneurial activities was included. We introduced a multiple regression equation to explain the relationship between those variables. The formula of the model is thus specified as follows:

where RC, AE, and EF stand for role conflict, academic experience, and entrepreneurial experience, respectively; β0 represents the control effect; β1 and β2 represent the main effect; β3 represents the moderating effect; and ε stands for the error term.

Measurement

Role conflict

According to Rizzo et al. (1970), we used a 5-item scale on a 7-point scale to measure role conflict, which has been used and validated in previous studies (Zou et al., 2019). The measurement items are “Taking teaching, research, and entrepreneurship into account, I often encounter conflicts in time distribution”, “Taking teaching, research, and entrepreneurship into account, I often encounter conflicts in problem-solving”, “Taking teaching, research, and entrepreneurship into account, I often doubt my pursuits”, “Taking teaching, research, and entrepreneurship into account, I feel that conflict exists in my knowledge structure” and “Taking teaching, research, and entrepreneurship into account, I often encounter conflict in my measurement system” (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). The Cronbach alpha value of the scale was 0.955.

Prior academic experience

According to Le and Kroll (2017), we adopted the total length of time engaged in teaching/research activities before participating in the current entrepreneurial project to measure prior academic experience, which was represented as the number of months. Previous studies have indicated that the quantified length of time can reflect experience to a great extent, which is an important means of measuring experience (Le & Kroll, 2017; Zhu & Chen, 2015).

Prior entrepreneurial experience

As we stated before, we adopted the total length of time engaged in entrepreneurial activities before participating in the current entrepreneurial project to measure prior academic experience, which is represented as the number of months. The reasons for choosing the time before participating in the current entrepreneurial project as a measure of prior experience is that we can capture sufficient variation in the prior experiences and ensure that these experiences were reasonably recent and closely related to the current role conflicts (Zhu et al., 2020).

Control variable

Eleven control variables from three aspects were included in our model. In terms of academic entrepreneurs, we controlled for gender, age, education, professional title, major, patents, and entrepreneurial support. In terms of institutions, we controlled for the Technology Transfer Office (TTO). In terms of firm, we controlled firm size, firm age and industry. These variables were added to the control model because they have been proven by previous studies to be closely related to role conflicts. For example, education and professional titles are closely related to individuals’ knowledge, which in turn affects their belief in value and time distribution when undertaking hybrid roles (Bartunek & Rynes, 2014; Jain et al., 2009). Entrepreneurship support was measured by whether the respondent’s parents are entrepreneurs, as the emotional and instrumental support they provide has been shown to be closely related to role conflicts (Jawahar et al., 2007). The TTO is an important organization linking academic staff to commercial opportunities and is an important factor that affects academic entrepreneurial activities (Balven et al., 2018).

To obtain accurate regression results, we checked potential common method variance and multicollinearity. First, we performed Harman’s single-factor test, and the results showed that the first factor explained 22.302% of the variance, which was far below the 50% threshold; this outcome suggests that the potential common method variance does not significantly impact the regression results. Second, to avoid multicollinearity, we centered prior academic experience and prior entrepreneurial experience before conducting the interaction effect. Furthermore, we calculated the variance expansion factor (VIF) of each regression model, and the results showed that the maximum VIF value was 1.44, which was less than the threshold of 10. Therefore, potential multicollinearity does not significantly affect the regression results.

Results

Correlation results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and correlations of the studied variables. The results showed that the variables were significantly related to each other, which provides initial support for our hypotheses. Some interesting correlations were found. We found that both professional title (r = 0.119, p < 0.01) and academic experience (r = 0.140, p < 0.001) were positively correlated with role conflict. This outcome can be explained by social learning theory. People with more academic experience are able to gain more academic knowledge, and they are more likely not to adapt to the logic of business activities after they become entrepreneurs. Similarly, people with higher professional titles are more suitable for the behavior patterns of scholars' roles and thus are more likely to experience role conflicts after they become entrepreneurs.

Regression results

Because our data were collected on a 5-point Likert scale, we adopted hierarchical regression to test our model. Table 2 shows the regression results of all hypotheses. All the control variables were added to model 1. Based on model 1, two independent variables were added to model 2, and model 3 was used to test the main effect. Model 4 and Model 5 were used to examine the moderating effect. Model 4 contained control variables, independent variables and moderating variables. Independent variables, moderating variables, and their interaction effect of independent variables and moderating variables were added into model 5 on the basis of model 1 to test the moderating effect. To avoid multicollinearity issues, we performed centralization with both the dependent variable and moderating variables before executing the interaction effect.

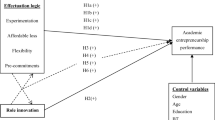

Hypothesis 1 predicted the relationship between prior academic experience and role conflict. The results in model 2 of Table 2 show a positive relationship between prior academic experience and role conflict (β = 0.191, p < 0.05). Thus, hypothesis 1 was supported. Hypothesis 2 predicted the relationship between prior entrepreneurial experience and role conflict. The results in model 3 of Table 2 show a negative relationship between prior entrepreneurial experience and role conflict (β = -0.142, p < 0.001). Thus, hypothesis 2 was supported. Hypothesis 3 predicted the moderating role of prior entrepreneurial experience. The results in Model 5 of Table 2 show that the interaction effect of prior academic experience and prior entrepreneurial experience has a negative impact on role conflict, which suggests that the relationship between prior academic experience and role conflict is negatively moderated by prior entrepreneurial experience (β = −0.179, p < 0.01). Thus, hypothesis 3 was supported. To better demonstrate the moderating role of prior entrepreneurial experience, we plotted the interaction effect in Fig. 2 with two levels of prior experience: high (one standard deviation over the mean) and low (one standard deviation below the mean). As illustrated in Fig. 2, academic experience positively affects role conflicts, and the influence of academic experience on role conflicts is more prominent with a short duration of entrepreneurial experience than a long duration of it, which further proves the existence of moderating effects.

Tests for robustness.

To test the robustness of our findings, we reran our regression model with an alternative measure of both prior academic experience and prior entrepreneurial experience. Stuart and Abetti (1990) indicated that the number of entrepreneurial projects that entrepreneurs have participated in is an important component of the entrepreneurial experience. Therefore, we used the number of startups that academic entrepreneurs had participated in before the current entrepreneurial project to measure their prior entrepreneurial experience. Additionally, Takeuchi et al. (2005) indicated that prior experience also varies in regard to breadth and depth. Accordingly, we argue that professional titles can represent the depth of academic entrepreneurship experience; thus, we used current job titles to measure prior academic experience, as individuals with higher professional titles are closer to scholarly identity in terms of time distribution, value and cognitive logic.

Table 3 shows the results of the regression, which suggest that both prior academic experience (β = 0.182, p < 0.05) and prior entrepreneurial experience (β = -0.209, p < 0.05) have a significant impact on role conflict and that their direction remains unchanged. Thus, our main effects were robust. Moreover, the interaction effect (β = -0.166, p < 0.1) of prior academic experience and prior entrepreneurial experience has a marginally significant impact on role conflict, which suggests the robustness of the moderating effect. Therefore, robust test results were consistent with the findings presented in this study.

Discussion

The model developed above is an attempt to provide insight into the antecedents of academic entrepreneurs’ role conflicts and to thereby deepen our understanding of why some academic entrepreneurs perceive more role conflict than others. We theorized that the difference in role conflict can be attributed to differences in two kinds of prior experience, namely, academic experience and entrepreneurial experience. Our empirical results suggested that academic entrepreneurs’ prior academic experience positively affects role conflict, while their entrepreneurial experience negatively affects role conflict. Moreover, we found that these two types of experience have an interaction effect such that the negative impact of prior academic experience on role conflict is weaker when they have more prior entrepreneurial experience. To check the robustness of our findings, we constructed an alternative measure of two kinds of prior experience to running an additional regression test and gained supportive robustness results. Our findings have several theoretical and practical contributions.

Theoretical contributions.

Our findings have several theoretical contributions. First, our findings contribute to the literature on the antecedents of academic entrepreneurs’ role conflicts by switching the focus from psychological cognitive factors to behavioral factors. Research on academic entrepreneurship has been devoted to exploring role conflict issues. A very large stream of research emphasizes that role conflict is often a result of psychological cognitive factors, such as social role identity (Bartunek & Rynes, 2014; Guo et al., 2019; Jain et al., 2009; Meek & Wood, 2016; Zou et al., 2019). Such insights are significant because they provide an explanation regarding how academic entrepreneurs manage their hybrid roles. However, this stream of research has overlooked the notion that role conflict is also inconsistent in regard to time arrangements and behavior patterns between roles (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985), which are more closely related to work skills and capacity than psychological cognitive factors (Hall, 1972). For academic entrepreneurs, the autonomy of academic and entrepreneurial activities is relatively high; thus, these individuals are more likely to perceive role conflicts in terms of time arrangement and specific behavior (Lumpkin et al., 2009). We contribute to research by focusing on the role of prior experience, which is a type of past behavior that widely affects individuals’ beliefs, knowledge, and skills (Baù et al., 2017; Rerup, 2005; Stuart & Abetti, 1990), in influencing academic entrepreneurs’ role conflict. The empirical findings provide insights into how prior experience affects academic entrepreneurs’ role conflict by shaping their knowledge and work competencies, thereby enriching the research on the antecedents of role conflict from a behavioral perspective.

Second, our findings contribute to the literature on prior experience in the field of entrepreneurship. Existing studies have suggested the important role of prior experience in launching entrepreneurial activities (Baù et al., 2017; Miralles et al., 2016), activating entrepreneurial motivation (Farmer et al., 2011), shaping entrepreneurial attitudes (Ucbasaran et al., 2010), developing opportunities (Dimov, 2010) and increasing the success rate of startups (Stuart & Abetti, 1987). However, the focus of most of these studies is on prior entrepreneurial experience. We contribute to this line of research by distinguishing and investigating the effects of two different types of prior experience—academic experience and entrepreneurial experience—and their interaction effect on academic entrepreneurs’ role conflict. By doing so, we also produce novel and even surprising insights. Our empirical results show that prior academic experience is positively related to role conflict, while prior entrepreneurial experience is negatively related to role conflict. This opposite relationship supports our propositions regarding both academic experience and entrepreneurial experience, and it has an important impact on role conflicts and our conception of distinguishing these two kinds of prior experience. Moreover, the interactive effect of prior academic experience and prior entrepreneurial experience is negatively related to role conflict, which implies that scholars with entrepreneurial experience show a higher acceptance of new entrepreneur roles as they are equipped with entrepreneurial-related knowledge and skills endowed by prior experience, thereby making it easier for them to develop a set of reactive role behaviors that meet two role expectations. By theoretically distinguishing the two types of prior experience, we have expanded the literature on prior experience in the field of entrepreneurship and laid the foundation for exploring the different results of different types of prior experience in the field of academic entrepreneurship.

Third, our findings also contribute to the research of academic entrepreneurs’ microidentity transition. Although an increasing stream of research has explored how academic entrepreneurs conduct microrole transitions between their scholarly role and entrepreneurial role in daily life (Jain et al., 2009; Zou et al., 2019), this literature has not yet considered the critical role of specific-domain knowledge and skills. In explaining how prior experience influences academic entrepreneurs’ role conflict, such as role values, time arrangement and behavior patterns, our research introduces social learning theory into role management research. We explain how the specific-domain knowledge and skills brought about by prior experience affect academic entrepreneurs’ microidentity transition when they adopt a hybrid role identity composed of a focal academic self and a secondary commercial persona in the early stage of academic entrepreneurship (Jain et al., 2009). We posit that the scholarly domain knowledge and skills brought about by academic experience strengthens the individuals’ focal academic self, thereby making them more deeply embedded in the already well-developed scholarly behavior model and further making it difficult to achieve microidentity transition. While entrepreneurial-domain knowledge and skills brought about by entrepreneurial experience would be of great help in reducing entrepreneurial uncertainty, individuals have sufficient material and psychological resources to balance the academic-entrepreneurship inconsistencies and then realize the microidentity transition. Therefore, our research indicates that prior entrepreneurial experience could be an important resource to help academic entrepreneurs conduct microidentity transition.

Practical implication

Our findings have several practical implications. First, our findings have practical implications for how scholars take steps to mitigate their role conflicts when they are engaged in commercial activities. Reducing role conflict is an urgent challenge for academic entrepreneurs. An important way to deal with this challenge is to learn entrepreneurial norms and skills to modify their extent of scholarly values and behavior patterns. Our study implies that scholars who intend to create a startup should be exposed to entrepreneurial information and knowledge for a substantial period of time so that they can overcome their existing scholarly behavioral inertia. For example, scholars can participate in business-related activities or entrepreneurial education before engaging in a formal entrepreneurship.

Second, our findings provide practical implications for resource holders to select academic entrepreneurial projects. Academic entrepreneurship activities are increasingly valued by universities and governments, as they are regarded as an important force for national innovation (Chang et al., 2016; Grimaldi et al., 2011). However, entrepreneurship is characterized by high risk and high failure levels (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006); thus, selecting promising entrepreneurial projects has become increasingly important for resource holders, such as investors, governments and schools. Our findings suggest that when evaluating entrepreneurial projects for promotion and funding purposes, resource holders should take into account the prior academic experience and entrepreneurial experience of academic entrepreneurs, including their length of experience, job title and total number of entrepreneurship endeavors.

Limitations and future research directions

Our research has several limitations, which also provide directions for future research. First, although we considered the geographical distribution of the samples, the subject distribution of the respondents was still limited. Specifically, the majority of the respondents represented the fields of economics, law, education, science, engineering, management, and military science, but there was a lack of respondents from the fields of philosophy, history, agriculture, medicine, and literature. Future research could consider using samples from all majors to validate our theoretical model or explore whether certain majors serve as boundary conditions of our conclusions. Second, the data used in the current study were collected from one source. Although the results of Harman’s single-factor test show that potential common method variance does not significantly impact the results, future research can obtain research data through multiple channels, especially focusing on collecting data on role conflict from entrepreneurial partners/family members (third parties). Third, although the current study reported multiple measurements of prior experience from different aspects in the robustness test to ensure validity, there were also other components of prior experience present. Future research can further develop other kinds of measurements of prior experience to validate our theoretical model, such as dividing prior entrepreneurial experience into prior entrepreneurial experience in the same industry and prior entrepreneurial experience in other industries.

Notes

For example, if there is a missing value in the role conflict scale, we regressed role conflict with the remaining 4 items. This method has been proven effective and efficient for self-reported scales, especially when the number of missing values is small (approximately 10%)(Shrive et al., 2006).

References

Abreu, M., & Grinevich, V. (2013). The nature of academic entrepreneurship in the UK: Widening the focus on entrepreneurial activities. Research Policy, 42(2), 408–422.

Ashforth, B. (2000). Role transitions in organizational life: An identity-based perspective. Routledge.

Ashforth, B., & Johnson, S. A. (2001). Which hat to wear? The relative salience of multiple identities in organizational contexts. In M. A. Hogg & D. J. Terry (Eds.), Social identity processes in organizational contexts (pp. 31–48). Psychology Press.

Balven, R., Fenters, V., Siegel, D. S., & Waldman, D. (2018). Academic entrepreneurship: The roles of identity, motivation, championing, education, work-life balance, and organizational justice. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(1), 21–42.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Bartunek, J. M., & Rynes, S. L. (2014). Academics and practitioners are alike and unlike: The paradoxes of academicpractitioner relationships. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1181–1201.

Baù, M., Sieger, P., Eddleston, K. A., & Chirico, F. (2017). Fail but try again? The effects of age, gender, and multiple–owner experience on failed entrepreneurs’ reentry. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 909–941.

Biddle, B. J. (1986). Recent developments in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 12(1), 67–92.

Bo, Z., Guo, J., Feng, G., Yan, S., & Li, Y. (2019). Who am i? the influence of social identification on academic entrepreneurs’ role conflict. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(2), 1–22.

Chang, Y.-C., Yang, P. Y., Martin, B. R., Chi, H.-R., & Tsai-Lin, T.-F. (2016). Entrepreneurial universities and research ambidexterity: A multilevel analysis. Technovation, 54, 7–21.

Clarke, J., & Holt, R. (2017). Imagery of ad-venture: Understanding entrepreneurial identity through metaphor and drawing. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(5), 476–497.

Clarysse, B., Tartari, V., & Salter, A. (2011). The impact of entrepreneurial capacity, experience and organizational support on academic entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 40(8), 1084–1093.

Dimov, D. (2010). Nascent entrepreneurs and venture emergence: Opportunity confidence, human capital, and early planning. Journal of Management Studies, 47(6), 1123–1153.

Endicott, L., Bock, T., & Narvaez, D. (2003). Moral reasoning, intercultural development, and multicultural experiences: Relations and cognitive underpinnings. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27(4), 403–419.

Farmer, S. M., Yao, X., & Kung-Mcintyre, K. (2011). The behavioral impact of entrepreneur identity aspiration and prior entrepreneurial experience. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(2), 245–273.

Fee, A., Gray, S. J., & Lu, S. (2013). Developing cognitive complexity from the expatriate experience: Evidence from a longitudinal field study. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 13(3), 299–318.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Gielnik, M. M., Spitzmuller, M., Schmitt, A., Klemann, D. K., & Frese, M. (2015). “I put in effort, therefore I am passionate”: Investigating the path from effort to passion in entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Journal, 58(4), 1012–1031.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88.

Grimaldi, R., Kenney, M., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2011). 30 years after Bayh–Dole: Reassessing academic entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 40(8), 1045–1057.

Guo, F., Zou, B., Guo, J., Shi, Y., Bo, Q., & Shi, L. (2019). What determines academic entrepreneurship success? A social identity perspective. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(3), 929–952.

Hall, D. T. (1972). A model of coping with role conflict: The role behavior of college educated women. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(4), 471–486.

Hayter, C. S. (2015). Social networks and the success of university spin-offs: Toward an agenda for regional growth. Economic Development Quarterly, 29(1), 3–13.

Hayter, C. S., Lubynsky, R., & Maroulis, S. (2017). Who is the academic entrepreneur? The role of graduate students in the development of university spinoffs. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(6), 1237–1254.

Jain, S., George, G., & Maltarich, M. (2009). Academics or entrepreneurs? Investigating role identity modification of university scientists involved in commercialization activity. Research Policy, 38(6), 922–935.

Jawahar, I., Stone, T. H., & Kisamore, J. L. (2007). Role conflict and burnout: The direct and moderating effects of political skill and perceived organizational support on burnout dimensions. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 142–159.

Jenkins, A. S., Wiklund, J., & Brundin, E. (2014). Individual responses to firm failure: Appraisals, grief, and the influence of prior failure experience. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 17–33.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall.

Le, S., & Kroll, M. (2017). CEO international experience: Effects on strategic change and firm performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(5), 573–595.

Li, M., Mobley, W. H., & Kelly, A. (2013). When do global leaders learn best to develop cultural intelligence? An investigation of the moderating role of experiential learning style. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 12(1), 32–50.

Li, Y., Zou, B., Guo, F., & Guo, J. (2020). Academic entrepreneurs’ effectuation logic, role innovation, and academic entrepreneurship performance: An empirical study. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16(9), 1–24.

Lin, S., Yamakawa, Y., & Li, J. (2019). Emergent learning and change in strategy: Empirical study of chinese serial entrepreneurs with failure experience. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(3), 773–792.

Lumpkin, G. T., Cogliser, C. C., & Schneider, D. R. (2009). Understanding and measuring autonomy: An entrepreneurial orientation perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(1), 47–69.

McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2006). Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 132–152.

Meek, W. R., & Wood, M. S. (2016). Navigating a sea of change: Identity misalignment and adaptation in academic entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(5), 1093–1120.

Méndez-Picazo, M. T., Galindo-Martín, M. A., & Castaño-Martínez, M. S. (2021). Effects of sociocultural and economic factors on social entrepreneurship and sustainable development. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 6(2), 69–77.

Miralles, F., Giones, F., & Riverola, C. (2016). Evaluating the impact of prior experience in entrepreneurial intention. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(3), 791–813.

Olugbola, S. A. (2017). Exploring entrepreneurial readiness of youth and startup success components: Entrepreneurship training as a moderator. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 2(3), 155–171.

Pascarella, E. T., Martin, G. L., Hanson, J. M., Trolian, T. L., Gillig, B., & Blaich, C. (2014). Effects of diversity experiences on critical thinking skills over 4 years of college. Journal of College Student Development, 55(1), 86–92.

Piaget, J. (1954). The child’s construction of reality. Basic Books.

Rerup, C. (2005). Learning from past experience: Footnotes on mindfulness and habitual entrepreneurship. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 21(4), 451–472.

Rizzo, J. R., House, R. J., & Lirtzman, S. I. (1970). Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 15(2), 150–163.

Rosenlund, J., & Legrand, C. (2021). Algaepreneurship as academic engagement: Being entrepreneurial in a lab coat. Industry and Higher Education, 35(1), 28–37.

Shibayama, S. (2012). Conflict between entrepreneurship and open science, and the transition of scientific norms. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 37(4), 508–531.

Shrive, F. M., Stuart, H., Quan, H., & Ghali, W. A. (2006). Dealing with missing data in a multi-question depression scale: A comparison of imputation methods. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(1), 1–10.

Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 224–237.

Stuart, R., & Abetti, P. A. (1987). Start-up ventures: Towards the prediction of initial success. Journal of Business Venturing, 2(3), 215–230.

Stuart, R. W., & Abetti, P. A. (1990). Impact of entrepreneurial and management experience on early performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 5(3), 151–162.

Takeuchi, R., Tesluk, P. E., Yun, S., & Lepak, D. P. (2005). An integrative view of international experience. Academy of Management Journal, 48(1), 85–100.

Toft-Kehler, R., Wennberg, K., & Kim, P. H. (2014). Practice makes perfect: Entrepreneurial-experience curves and venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(4), 453–470.

Ucbasaran, D., Westhead, P., Wright, M., & Flores, M. (2010). The nature of entrepreneurial experience, business failure and comparative optimism. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(6), 541–555.

Zhan, S., Uy, M. A., & Hong, Y.-Y. (2020). Missing the Forest for the Trees: Prior Entrepreneurial Experience, Role Identity, and Entrepreneurial Creativity. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258720952291

Zhu, D. H., & Chen, G. (2015). CEO narcissism and the impact of prior board experience on corporate strategy. Administrative Science Quarterly, 60(1), 31–65.

Zhu, Q., Hu, S., & Shen, W. (2020). Why do some insider CEOs make more strategic changes than others? The impact of prior board experience on new CEO insiderness. Strategic Management Journal, 41(10), 1933–1951.

Zou, B., Guo, J., Guo, F., Shi, Y., & Li, Y. (2019). Who am I? The influence of social identification on academic entrepreneurs’ role conflict. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(2), 363–384.

Acknowledgements

This submission includes no observations that have been used in another published or planned published paper. All three authors have equally contributed to the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the National Natural Science Foundation of China Youth Science Fund Project (No 0.71704073) and the Major Project of National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 19ZDA116).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Mo, Y. & Wang, D. Why do some academic entrepreneurs experience less role conflict? The impact of prior academic experience and prior entrepreneurial experience. Int Entrep Manag J 17, 1521–1539 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-021-00764-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-021-00764-4