Abstract

Public support to conservation is motivated by factors such as the desire to preserve/exploit the economic value of nature, moral concerns about the treatment of sentient animals, or appreciation of nature’s aesthetics. Species that are particularly well suited to mobilize public support, raise awareness, and stimulate conservation actions are often referred to as flagship species. The Antillean manatee is an endangered aquatic mammal that inhabits tropical and subtropical bays, lagoons, and estuaries of the Western Atlantic. They frequently enter mangrove habitats searching for food and freshwater and may use the area as nursery habitats. Habitat loss is a major threat to extant populations and mangrove degradation generates a high frequency of stranding of dependent pups. Between 1994 and 2009, the manatee reintroduction program already rescued and rehabilitated 46 individuals, successfully releasing 76% of them. Ecotourism based on manatee watching at Tatuamunha River, Alagoas State, has been a successful strategy for promoting conservation and providing opportunities for social inclusion of local communities. The presence of a large and charismatic marine mammal provides a unique opportunity for raising conservation awareness, promoting ecotourism and scientific research, mobilizing conservation funding, and engaging local populations, making manatees an ideal flagship species to the conservation of mangroves of northeast Brazil.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Conservation actions, such as creating a new protected area or reintroducing an endangered species, are the expression of people’s desire to preserve the elements of the natural world that they value (Ladle et al. 2011). The continued success of conservation, therefore, depends to a greater or lesser degree on public support (Kareiva and Marvier 2012). Such support is motivated by a range of factors, including the desire to preserve/exploit the economic value of nature, moral concerns about the treatment of sentient animals, or appreciation of nature’s aesthetics (reviewed in Newman et al. 2017). Clearly, not all species or landscapes can mobilize similar levels of public support or affection, leading conservationists to foreground certain characteristics of biodiversity depending on the conservation outcomes they want to achieve.

Species that are particularly well suited to mobilize public support, raise awareness, and stimulate conservation actions are often referred to as “flagship species” (Heywood 1995; Verissimo et al. 2011). These species often share traits (e.g., large size, charisma, distinct physical appearance), though their choice as focal points for conservation initiatives ultimately depends on the specific conservation objectives (Verissimo et al. 2011). This principle was formalized by Barua et al. (2011) who identified a suite of ecological and cultural traits of flagship species associated with seven different types of conservation action (Table 13.1).

It becomes clear from Table 13.1 that a single flagship species may possess traits that predispose it to be used in several types of conservation strategies. Here, we argue that this is the case of the Antillean manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus) in Brazil, a large and charismatic aquatic mammal whose continued existence critically depends on the conservation of the highly threatened mangrove habitats that it uses. In the following sections, we will present a case for the Antillean manatee as a flagship species for mangrove conservation in Brazil, highlighting its symbolic value and the multiple conservation actions that it can support.

2 The West Indian Manatee (Trichechus manatus): Biogeography, Ecology, and Cultural Value

The West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus Linnaeus 1785) is an aquatic mammal that inhabits tropical and subtropical areas of the Western Atlantic. It occurs in bays, lagoons, and estuaries (Folkens and Reeves 2002), ranging from Rhode Island, in the USA, to Alagoas in Northeastern Brazil (Albuquerque and Marcovaldi 1982) (see Chap. 3, Maps 1–9). Two subspecies of the West Indian manatee are currently recognized: the Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) and the Antillean manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus) (Committee on Taxonomy 2016). The distribution of the latter stretches from the east coast of Mexico and Central America to the northern and northeastern coasts of South America and the Caribbean Sea (Lefebvre et al. 1989).

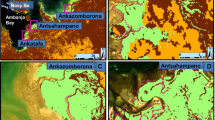

The distribution of Antillean manatees on the Brazilian coast is highly fragmented, with a particularly large gap between the subpopulation in the north of Alagoas State and south of Pernambuco State and the one in the west of Ceará and Maranhão states (Albuquerque and Marcovaldi 1982; Borobia and Lodi 1992; Luna et al. 2008) (Fig. 13.1). At one time manatees were relatively abundant along the Brazilian coast (Fig. 13.1), ranging as far south as Espírito Santo State (Whitehead 1977). However, a small population size and long periods of isolation have caused low genetic diversity among extant populations (García-Rodríguez et al. 1998; Vianna et al. 2006; Luna et al. 2012).

West Indian manatees are habitat generalists, occurring in lakes, rivers, estuaries, and shallow coastal waters where they feed on a wide variety of submerged, floating and emergent vegetation (Fig. 13.2), including mangrove leaves (Spiegelberger and Ganslosser 2005) and roots (Normande, pers. obs.). Being mainly herbivorous, they need to spend between 6 and 8 h per day foraging (Marsh et al. 2011; Allen et al. 2017). A study conducted in Rio Grande do Norte, Paraíba, and Alagoas states (Borges et al. 2008) identified 17 species of macroalgae consumed by manatees, including red algae, two species of marine phanerogams (i.e., Halodule wrightii and Halophila sp.), as well as cnidarians. Similarly, on the northern and northeast coasts of Brazil, manatees have been observed to consume the plants Montrichardia arborescens, Spartina brasiliensis, Eichornia crassipes, Eleocharis spp., Crenea maritima, Cyperus spp., and Blutaparon portulacoides, and the leaves of mangrove species Avicennia spp., Laguncularia racemosa, and Rhizophora mangle (Borges et al. 2008; Lins et al. 2014). There are even reports of manatees consuming fish, illustrating the opportunistic nature of the diet of this species (Sousa et al. 2013; Meirelles and Carvalho 2016).

As might be expected with such a generalist feeder, feeding preference appears to be very variable in time and space and is related to availability, nutritional value, and palatability of different types of vegetation (Meirelles et al. 2018). Even when mangrove vegetation does not make up a substantial proportion of their diet, manatees still frequently enter mangrove-lined estuaries and bays in search for food and freshwater (Normande et al. 2015). This is confirmed by stable isotope analysis of manatees from the north and northeast of Brazil which indicated that individuals predominantly graze in estuarine and freshwater environments (Ciotti et al. 2014). More generally, there is a large overlap in the historical distribution of mangroves and manatees in Brazil, with the former dominating coastal habitats as far south as Santa Catarina State and the latter being limited to the southern coast of Alagoas State nowadays (Fig. 13.1).

Environmental factors such as water temperature, depth, hydrological cycle, and proximity of freshwater sources can influence sirenian distributions within and between habitats (Irvine 1983; Reid et al. 1991; Oliveira-Gómez and Mellink 2005; Sheppard et al. 2006; Castelblanco-Martínez et al. 2009). In Florida, seasonal fluctuations in water temperature play an important role in determining habitat use of manatees, since they use warm water sites during winter (Whitehead 1977; Irvine 1983; Reid et al. 1991). However, in tropical and subtropical areas such as northeast Brazil, water temperature shows far less variability and is therefore unlikely to strongly influence manatee habitat use (Deutsch et al. 2003).

Despite more stable water temperatures in the tropics, seasonal migrations have been observed in Antillean manatees in Mexico (Colmenero-Rolón and Hoz-Zavala 1986), Honduras (Rathbun et al. 1983), and Trinidad (Reynolds III and Odell 1991). Reeves et al. (1988) also observed seasonal migrations in African manatees (Trichechus senegalensis), and Best (1983) and Arraut et al. (2017) recorded the same behavior in Amazonian manatees (Trichechus inunguis). In the latter cases, the populations inhabit freshwater systems far from the coast, and seasonal migration was associated with fluctuations in food availability and habitat accessibility caused by seasonal fluctuations in water level (Deutsch et al. 2003).

Coastal populations of Antillean manatees may show smaller-scale variation in habitat use. For example, Normande et al. (2015) observed more intensive use of estuaries than marine environments using radiotelemetry data from 21 reintroduced manatees in northeast Brazil. This pattern may be related to the increased concentration of freshwater sources in estuaries, though it may also be related to the presence of soft-release (acclimatization) enclosures that the manatees may associate with being fed as released manatees tend to spend some time using the area around the acclimatization facilities (Fig. 13.2). In Alagoas, Pernambuco, and Paraíba states, freshwater sources available to the manatees are mainly concentrated in rivers. This is somewhat different from Ceará and Rio Grande do Norte states, where freshwater springs in the sea floor are more abundant. Consequently, the manatees in the southernmost subpopulation are more dependent on estuaries and mangroves and more frequently observed in these ecosystems.

Mangrove forests provide an abundance of water sources for manatees, from natural springs to runoff from leaves and roots. They are also very effective at protecting the coastline from erosion and trapping sediment (Almeida et al. 2008). This, in turn, prevents the estuaries from the worst effects of sedimentation and ensures a sufficient water depth for manatees to access a large proportion of the habitat. It is also important to note that despite the high abundance of manatee food sources on the shallow inshore reefs (which act as excellent substrates for algae fixation), many of these areas are only accessible during high tides. This limited access may partly explain the relatively low frequency of observation of utilization of reefs in northeast Brazil (Normande et al. 2015). Again, this contrasts with Rio Grande do Norte State, where Paludo and Langguth (2002) noted that manatees predominantly use reefs that are densely colonized by algae.

Mangrove ecosystems may also act as important nursery habitats for manatees. In northeast Brazil, manatee calves have been observed in the estuary of the Maracaípe River in Pernambuco (Lima et al. 2005) and the Timonha-Ubatuba complex on the border between the states of Ceará and Piauí (Magnus Machado Severo, pers. comm.) (see Chap. 3, Map 4). The coasts of the neighboring states of Rio Grande do Norte and Ceará are characterized by high rates of neonate stranding (Balensiefer et al. 2017). This is generally attributed to the degraded state of the local estuaries, with heavily silted rivers restricting the access of pregnant females into the estuaries and forcing them to give birth in the open sea (Meirelles 2008).

3 Manatee Conservation: Threats and Actions

The West Indian manatee is classified as vulnerable by IUCN (2019). In Brazil, the situation is more alarming, and the species is considered endangered by the federal government (Luna et al. 2018). The entire Brazilian population has been estimated at only 500 individuals based on questionnaires with fishermen and coastal residents (Lima 1999; Luna 2001). IUCN (2012) suggests that this number may be as low as 200, although they did not provide details on the methods used to estimate population size. It should be noted, however, that despite their large size, manatees are very difficult to survey (as are most marine mammals). Indirect population estimates based on extrapolation of genetic data (Luna et al. 2012) suggest that the Brazilian population of T. manatus could have as high as 1,000 individuals.

The most recent direct population estimate of Brazilian manatees was made by aerial surveys and covered more than 1500 km of coast, from the border between the states of Alagoas and Sergipe to the border between the states of Piauí and Maranhão (Alves et al. 2015). This study estimated an average of 1104 individuals along the surveyed coast, although the data is likely to cause an underestimation due to the low detectability of manatees in locations with turbid waters such as estuaries and within mangroves. The highest density of individuals was observed in the estuary complex of Timonha-Ubatuba and Cardoso-Camurupim Rivers, formed by a group of islands with well-preserved estuaries and bays, with five animals found within the estuarine complex (Alves et al. 2015). This result confirms the enormous importance of protected areas for the Brazilian manatee population, especially those that are large enough to protect one or more estuarine complexes in their totality such as the Delta do Parnaíba Environmental Protected Area (Maranhão, Piauí, and Ceará States) and the Costa dos Corais Environmental Protected Area (Pernambuco and Alagoas States) (see Chap. 3, Maps 4 and 8, respectively).

Although there is a lack of baseline data, there are good reasons to believe that the Brazilian manatee population was orders of magnitude larger in the precolonial period. Such large, docile animals were easy targets for predatory hunting and there was a ready market for manatee meat, skin, and oil during the early colonization of the country (ICMBio 2011). Manatee hunting is now almost nonexistent on the northeast coast, although it is still practiced in the north of Brazil where it may account for as much as 86% of recorded mortalities (Luna 2001). Other threats to manatees include accidental death by getting entangled in fishing gear (Parente et al. 2004; Meirelles 2008) or by collisions with motorized boats (Borges et al. 2007).

Habitat loss is also a major threat to extant populations. Loss of mangroves and degradation of estuaries may be especially important since these provide manatees with clean water to drink and calm conditions to feed and reproduce. Mangroves are particularly vulnerable to the deleterious effects of the growth of socioeconomic activities and the disorderly expansion of urban centers, which impose severe changes on the quality of estuarine waters, bays, lagoons, and coastal lagoons (see Chap. 16). The recent approval of the New Forest Code, Federal Law no. 12,651/2012, may put further pressure on Brazil’s mangroves, since the new law allows the use of 35% of mangroves in the northeast for shrimp farming (Rovai et al. 2012; Schaeffer-Novelli et al. 2012). The loss of mangroves is also associated with increased silting and pollution, further reducing the quality of the habitat for manatees (Lima et al. 2011).

Habitat degradation due to the loss of mangroves is currently considered the main threat to the conservation of Antillean manatees in Brazil (Campos et al. 2003). The impact of this degradation can be seen in an increased frequency of stranding of dependent pups. Such strandings are probably caused by females being excluded from traditional nursing grounds within estuaries and giving birth in suboptimal habitats in the open sea. This increases the probability of separation between mother and calf and ultimately leads to the stranding of neonates and juveniles (Lima 1999). As many as 83% of manatee deaths in Ceará State were classified as dependent offspring, with death through entanglement in fishing gear representing only 12.5% of deaths (Meirelles 2008).

In a global context, sirenian conservation initiatives are primarily focused on the creation and implementation of protected areas and on introducing measures to reduce illegal hunting, such as environmental education and inspection activities. The expansion of scientific knowledge on distribution, habitat use, and population parameters is also a priority in national conservation action plans (ICMBio 2011, 2018). A recent expansion of small purpose-built rehabilitation centers for dependent pups (e.g., in Puerto Rico and Belize) is being recorded, with the purpose of rehabilitation and release of rescued individuals. Specialized rehabilitation centers have also been constructed in Brazil, supported by on-call rescue teams that bring in stranded orphaned cubs for treatment and rehabilitation. The federal conservation agency (Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade [ICMBio]) works in partnership with these organizations to release rehabilitated animals into ecologically appropriate locations that are closest to the stranding sites.

In 1980, the Brazilian federal government created the Peixe-boi (“Manatee”) Project to carry out research and actions that would reduce the threat of extinction to Antillean manatees in the country. Among the many actions carried out over 42 years of the project, two are particularly worthy of note: (i) rescue and rehabilitation of stranded dependent pups, followed by release (and monitoring) in a natural environment, and (ii) extensive environmental education initiatives aimed at reducing intentional hunting (Luna and Passavante 2010).

3.1 The Brazilian Antillean Manatee Reintroduction Program

The manatee reintroduction program was initiated in 1994 to connect isolated populations, minimizing inbreeding depression and loss of diversity through genetic drift and recolonizing parts of the historical distribution of the subspecies (Lima et al. 2007). Release sites were selected at the beginning of the program using criteria based on the availability of food and fresh water, the existence of protected areas, release logistics, and level of human occupation (Table 13.2). From 1994 to 2019, 46 rescued and rehabilitated individuals have been released at three different sites (Fig. 13.1): Paripueira and Porto de Pedras (Fig. 13.3) in Alagoas State and Rio Tinto in Paraíba State, with a success rate of approximately 76% (Normande et al. 2015) (see Chap. 3, Maps 7 and 9).

A total of six reintroduced females gave birth to 13 pups, with one individual “Lua” giving birth to five pups (three alive and two dead) (Attademo et al. 2022). These pups were born and raised in a natural environment assisting in restocking populations. The offspring of reintroduced females were all born in Alagoas, in the estuaries of the Manguaba, Tatuamunha, São Miguel, and Santo Antônio rivers. These sites were used by females for both parturition and parental care (ICMBio, unpublished data) (see Chap. 3, Map 9).

Among the three release sites, only Porto de Pedras did not contain an extant free-living population of manatees; this area is considered a historical occurrence site and is located between two isolated populations (Lima 1999). In this way, the releases at Porto de Pedras (Figs. 13.1 and 13.3) are considered reintroductions, while the releases at Paripueira and Tinto rivers (Fig. 13.1) are examples of reinforcement (sensu IUCN 1998) of native manatee populations.

Before release, rehabilitated manatees received radio transmitters with VHF and satellite technology to monitor their post-release movements. This monitoring aims at assessing the adaptation of individuals to the environment and enabling veterinary interventions in case of debilitated individuals and collecting information on movement and habitat use by released animals. Such information increases scientific knowledge about this subspecies and its ecological relationships, as well as contributes to the evaluation of the effectiveness of the management program for conservation (Lima et al. 2007).

3.2 Community Conservation and Ecotourism

Ecotourism based on manatee watching on the Tatuamunha River near the release site at Porto de Pedras began to develop in the late 1990s. It has been a very successful strategy, promoting conservation and providing opportunities for social inclusion and income generation for local communities (Normande et al. 2015). The first trips were organized informally with local fishermen, who would act as guides and take tourists on their rafts (“jangadas”) to view manatees in sheltered areas of the inshore reef and the mangrove-lined estuary. These guides were native to the municipalities of Porto de Pedras and São Miguel dos Milagres and typically had very basic formal education. With the initiation of the release program (see above), manatees became even easier to locate and there was a growing realization that organized manatee watching represented a substantial source of supplementary income for local communities.

The first trips visited a range of habitats where the manatees had a higher chance to be found and were completely unregulated, with tourists frequently swimming around and feeding and touching the manatees. This led to increasing levels of habituation to human presence, a potentially negative process that can lead to harmful behaviors such as approaching motorized boats and making individuals more vulnerable to hunting. With the development of the release program and the associated increase in opportunities for manatee viewing, it became apparent that there was an urgent need to develop an educational, participative process to encourage best practices among the ecotourism providers. This was achieved through extensive dialogue with the local community at every step in the process, with the goal of ensuring that the manatee watching was environmentally and economically sustainable, causing the least possible disturbance to the released and wild individuals. It is important to note that not all members of the local community were in favor of the release program, with some fishermen complaining that the increased population of manatees was damaging their nets.

The first steps towards the formalization of manatee watching in Porto de Pedras began in 2006, when technicians of the “Peixe-Boi” Project, under the responsibility of the Brazilian government, began to train the local guides and to formulate a set of normative practices. From 2007 to 2009 there were three training courses for manatee watching guides. Initially, there were 16 participants in the training program, though this number expanded to a fixed number of 20 accredited guides, and other supporting staff, currently operating in the area. Between 2009 and 2010 a formal set of rules and procedures, logistics, training, accreditation, and division of responsibility was established after extensive negotiations between guides, municipal government, and ICMBio, the latter responsible for project management. In 2013, the standards were revised and adapted for publication in the Coral Coast Environmental Protection Area Management Plan, where the release site is inserted.

An important aspect of the development of manatee ecotourism in Porto de Pedras was the creation of the Association of Manatee Watching Tourism Guides in 2009. This organization is responsible for representing guides, marketing, and conducting daily tours (see Fig. 13.4). The association currently provides up to 10 departures and a maximum of 70 people a day all year round. Significantly, it provides substantial livelihood benefits, being the main source of income for more than 50 local families, in addition to developing educational projects, joint community biodiversity monitoring, and assisting ICMBio and other partners in the management and conservation of the manatees, mangroves, and reefs.

4 Final Remarks

Based on the criteria suggested by Barua et al. (2011) (Table 13.1), manatees are an ideal flagship species for mangrove conservation in northeast Brazil. First, they are strongly associated with mangrove ecosystems, spending a high proportion of their time in or around estuaries (Normande et al. 2015). Second, manatees can act as an umbrella species, whose protection serves to protect many co-occurring species (Roberge and Angelstam 2004). In northeast Brazil, conserving the mangroves is essential for providing nursing and feeding areas for manatees. Moreover, manatee conservation also provides a strong justification for conserving the local reefs. Third, the manatee is widely perceived as an endangered species, proving a strong justification for prioritizing the protection of its ecosystem. Fourth, given this species is recognizable, is easily observed, and has unique morphological and behavioral traits, the interactions with manatees produce memorable experiences. Fifth, manatees in northeast Brazil typically have positive cultural associations and, due to their frequent interactions with local fishermen, there is considerable local ecological knowledge within coastal communities. Finally, they have a relevant scientific value, especially in the fields of ecology and animal behavior.

In conclusion, the presence of a large, charismatic marine mammal within the mangrove habitats of northeast Brazil provides a unique opportunity for raising conservation awareness, promoting ecotourism and scientific research, mobilizing conservation funding, and engaging local populations in the conservation of mangroves.

References

Albuquerque C, Marcovaldi GM (1982) Ocorrência e distribuição do peixe-boi marinho no litoral brasileiro (Sirenia, Trichechidade, Trichechus manatus, Linnaeus 1758). In: Abstracts of Simpósio Internacional sobre a Utilização de Ecossistemas Costeiros: Planejamento, Poluição e Produtividade, Rio Grande

Allen AC, Beck CA, Bonde RK, Powell JA, Gomez NA (2017) Diet of the Antillean manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus) in Belize, Central America. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 98(7):1831–1840

Almeida R, Coelho C Jr, Corets E (2008) Impactos Humanos Sobre os Manguezais in: Guia Didático: Os Maravilhosos Manguezais do Brasil. Papagaya Editora, Vitória, pp 1–3

Alves MD, Kinas PG, Marmontel M, Borges JCG, Costa AF, Schiel N, Araújo ME (2015) First abundance estimate of the Antillean manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus) in Brazil by aerial survey. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 96(SI4):955–966

Arraut EM, Arraut JL, Marmontel M, Mantovani JE, Novo EMLM (2017) Bottlenecks in the migration routes of Amazonian manatees and the threat of hydroelectric dams. Acta Amaz 47:7–18

Attademo FLN, Normande IC, Sousa GP, Costa AF, Borges JCG, de Alencar AEB, Foppel EFdaC, Luna FdeO (2022) Reproductive success of Antillean manatees released in Brazil: implications for conservation. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315422000443

Balensiefer DC, Loffler F, Attademo N, Sousa P, Carlos A, Carneiro G, Emı A, Silva DL (2017) Three decades of Antillean manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus) stranding along the Brazilian coast. Trop Conserv Sci 10:1–9

Barua M, Root-Bernstein M, Ladle RJ, Jepson P (2011) Defining flagship uses is critical for flagship selection: a critique of the IUCN climate change flagship fleet. Ambio 40:431–435

Best RC (1983) Apparent dry season fasting in Amazonian manatees (Mammalia: Sirenia). Biotropica 15:61–64

Borges JCG, Emmanuel G, Miranda C (2008) Identificação de itens alimentares constituintes da dieta dos peixes-boi marinhos (Trichechus manatus) na região Nordeste do Brasil. Biotemas 21:77–81

Borges JCG, Vergara-Parente JE, de Carvalho Alvite CM, Marcondes MCC, de Lima RP (2007) Embarcações motorizadas: uma ameaça aos peixes-bois marinhos (Trichechus manatus) no Brasil. Biota Neotrop 7(3):199–204

Borobia M, Lodi L (1992) Recent observations and records of the west Indian manatee Trichechus manatus in northeastern Brazil. Biol Conserv 59:37–43

Campos AA, Monteiro AQ, Monteiro-Neto C, Pollete M (2003) A Zona Costeira do Ceará: diagnóstico para a Gestão Integrada, 248 pp. AQUASIS, Fortaleza

Castelblanco-Martínez DN, Bermúdez-Romero AL, Gómez-Camelo IV, Rosas FCW, Trujillo F, Zerda-Ordoñez E (2009) Seazonality of habitat use, mortality and reproduction of the vulnerable Antillean manatee Trichechus manatus manatus in the Orinoco River, Colombia: implications for conservation. Oryx 43(2):235–242

Ciotti LL, Luna FO, Secchi ER (2014) Intra-and interindividual variation in d13C and d15N composition in the Antillean manatee Trichechus manatus manatus from northeastern Brazil. Mar Mamm Sci 30:1238–1247

Colmenero-Rolón L, Hoz-Zavala M (1986) Distribución de los manatíes, situación y su conservación en México. An del Inst Biol 56:955–1020

Committee on Taxonomy (2016) List of marine mammal species and subspecies. https://www.marinemammalscience.org/species-information/list-marine-mammal-species-subspecies/

Deutsch CJ, Reid JP, Bonde RK, Easton DE, Kochman HI, O’Shea TJ (2003) Seasonal movements, migratory behavior, and site fidelity of West Indian manatees along the Atlantic coast of the United States. Wildlife Monogr 151:1–77

Folkens PA, Reeves RR (2002) Guide to marine mammals of the world. National Audubon Society, New York City

García-Rodríguez AI, Bowen BW, Domning D, Mignucci-Giannoni AA, Marmontel M, Montoya-Ospina RA, McGuire PM (1998) Phylogeography of the West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus): how many populations and how many taxa? Mol Ecol 7:1137–1149

Heywood VH (1995) Global biodiversity assessment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade – ICMBio (2011) Plano de ação nacional para a conservação dos sirênios: peixe-boi-da-amazônia Trichechus inunguis e peixe-boi-marinho Trichechus manatus. ICMBio, Brasília

Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade – ICMBio (2018) Plano Nacional para a Conservação do Peixe-boi marinho. Portaria n° 249 de 04 de abril de 2018. ICMBio, Brasília

Irvine AB (1983) Manatee metabolism and its influence on distribution in Florida. Biol Conserv 25:315–334

International Union for Conservation of Nature – IUCN (1998) Guidelines for re-introduction. Prepared by the IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland

International Union for Conservation of Nature – IUCN (2012) IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, version 2011

International Union for Conservation of Nature – IUCN (2019) The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, version 2019–1. http://www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed 21 Mar 2019

Kareiva P, Marvier M (2012) What is conservation science? Bioscience 62:962–969

Ladle RJRJ, Jepson P, Gillson L (2011) Social values and conservation biogeography. In: Ladle RJ, Whittaker RJ (eds) Conservation biogeography. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, pp 13–30

Lefebvre LW, O’Shea TJ, Rathbun GB, Best RC (1989) Distribution, status, and biogeography of the West Indian manatee. In: Woods CA (ed) Biogeography of the West Indies: past, present and future. Sandhill Crane Press, Gainesville, pp 567–620

Lima RP (1999) Peixe-boi marinho (Trichechus manatus): distribuição, status de conservação e aspectos tradicionais ao longo do litoral Nordeste do brasil. IBAMA, Brasília

Lima RP, Alvite CMC, Vergara-Parente JE (2007) Protocolo de reintrodução de peixes-bois marinhos no Brasil. IBAMA/MMA & Instituto Chico Mendes, São Luís

Lima RP, Alvite CMC, Vergara-Parente JE, Castro DF, Paszkiewicz E, Gonzalez M (2005) Reproductive behavior in a captive-released manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus) along the Northeastern Coast of Brazil and the life history of her first calf born in the wild. Aquat Mamm 31:420–426

Lima RP, Paludo D, Soavinski RJ, Silva KG, Oliveira EMA (2011) Levantamento da distribuição, ocorrência e status de conservação do Peixe-Boi Marinho (Trichechus manatus, Linnaeus, 1758) no litoral nordeste do Brasil. Nat Resour 1:41–57

Lins ALFA, Gurgel ESC, Bastos MNC, Sousa MEM, Emin-Lima R (2014) Which aquatic plants of the intertidal zone do manatees of the Amazon estuary eat? Sirenews 62:11–12

Luna FO (2001) Distribuição, status de conservação e aspectos tradicionais do peixe-boi marinho (Trichechus manatus) no litoral Norte do Brasil. Master Thesis, 122 pp, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco

Luna FO, Araújo JP, Passavante JZ, Mendes PP, Pessanha M, Soavinski RJ, Oliveira EM (2008) Ocorrência do peixe-boi marinho (Trichechus manatus manatus) no litoral norte do Brasil. Bol Mus Biol Mello Leitão 23(3):37–49

Luna FO, Balensiefer DC, Fragoso AB, Stephano A, Attademo FLN (2018) Trichechus manatus. In: Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção. ICMBio/MMA, Brasília, pp 103–109

Luna FO, Bonde RK, Attademo FLN, Saunders JW, Meigs-Friend G, Passavante JZO, Hunter ME (2012) Phylogeographic implications for release of critically endangered manatee calves rescued in Northeast Brazil. Aquat Conserv 22:665–672

Luna FO, Passavante JZO (2010) Projeto peixe-boi/ICMBio: 30 anos de conservação de uma espécie ameaçada. ICMBio, Brasília

Marsh H, O’Shea TJ, Reynolds JE III (2011) Ecology and conservation of Sirenia: dugongs and manatees. Cambridge University Press, New York

Meirelles ACO (2008) Mortality of the Antillean manatee, Trichechus manatus manatus, in Ceará State, North-Eastern Brazil. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 88:1133–1137

Meirelles ACO, Carvalho VL (2016) Peixe-boi-marinho - Biologia e Conservação no Brasil, 1st edn. Bambu Editora e Artes Gráficas, São Paulo

Meirelles ACO, Carvalho VL, Marmontel M (2018) West Indian manatee Trichechus manatus in South America: distribution, ecology and health assessment. In: Rossi-Santos M, Finkl C (eds) Advances in marine vertebrate research in Latin America. Springer, Cham, pp 263–291

Newman JA, Varner G, Linquist S (2017) Defending biodiversity: environmental science and ethics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Normande I, Luna F, Malhado A, Borges J, Viana Junior P, Attademo F, Ladle R (2015) Eighteen years of Antillean manatee Trichechus manatus manatus releases in Brazil: Lessons learnt. Oryx, 49(2):338–344. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605313000896

Oliveira-Gómez LD, Mellink E (2005) Distribution of the Antillean manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus) as a function of habitat characteristics, in Bahía de Chetumal, México. Biol Conserv 121:127–133

Paludo D, Langguth A (2002) Use of space and temporal distribution of Trichechus manatus manatus Linnaeus in the region of Sagi, Rio Grande do Norte State, Brazil (Sirenia, Trichechidae). Rev Bras Zool 19:205–215

Parente CL, Vergara-Parente JE, Lima RP (2004) Strandings of Antillean manatees, Trichechus manatus manatus, in northeastern Brazil. Lat Am J Aquat Mamm 3(1):69–75

Rathbun GB, Powell JA, Cruz G (1983) Status of the West Indian manatee in Honduras. Biol Conserv 26:301–308

Reeves RR, Tuboku-Metzger D, Kapindi RA (1988) Distribution and exploitation of manatees in Sierra Leone. Oryx 22:75–84

Reid JP, Rathbun GB, Wilcox JR (1991) Distribution patterns of individually identifiable West Indian manatees (Trichechus manatus) in Florida. Mar Mamm Sci 7(2):180–190

Reynolds JE III, Odell DK (1991) Manatees and dugongs, 192 pp. Facts on File Inc, New York

Roberge J, Angelstam P (2004) Usefulness of the umbrella species concept as a conservation tool. Conserv Biol 1:76–85

Rovai AS, Menghini RP, Schaeffer-Novelli Y, Molero GC, Coelho-Jr C (2012) Protecting Brazil’s coastal wetlands. Science 335(6076):1571–1572

Schaeffer-Novelli Y, Rovai AS, Coelho-Jr C, Menghini RP, Almeida R (2012) Alguns impactos do PL30/2011 sobre os manguezais brasileiros. In: Código Florestal e a Ciência: o que nossos legisladores ainda precisam saber. Comitê Brasil, Brasília, pp 18–27

Sheppard JK, Preen AR, Marsh H, Lawler IR, Whiting SD, Jones RE (2006) Movement heterogeneity of dugongs, Dugong dugon (Müller), over large spatial scales. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 334:64–83

Sousa MEM, Martins BML, Fernandes MEB (2013) Meeting the giants: the need for local ecological knowledge (LEK) as a tool for the participative management of manatees on Marajó Island, Brazilian Amazonian coast. Ocean Coast Manag 86:53–60

Spiegelberger T, Ganslosser U (2005) Habitat analysis and exclusive bank feeding of the Antillean manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus L. 1758) in the Coswine Swamps of French Guiana, South America. Trop Zool 18:1–12

Verissimo D, MacMillan DC, Smith RJ (2011) Toward a systematic approach for identifying conservation flagships. Conserv Lett 4:1–8

Vianna JA, Bonde RK, Caballero S, Giraldo JP, Lima RP, Clark A, Rodríguez-Lopez MA (2006) Phylogeography, phylogeny and hybridization in trichechid sirenians: implications for manatee conservation. Mol Ecol 15:433–447

Whitehead PJP (1977) The former southern distribution of New World manatees (Trichechus spp.). Biol J Linn Soc 9:165–189

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade Conservation, Fundação Toyota do Brasil, FundaÓÐo SOS Mata Atlântica, and Fundo Brasileiro para a Biodiversidade for current logistics and financial support and all professionals that dedicated their lives to manatee conservation in Brazil.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Normande, I.C., Costa, A.F., Coelho-Jr, C., dos Santos, J.U., Ladle, R.J. (2023). Flagship Species: Manatees as Tools for Mangrove Conservation in Northeast Brazil. In: Schaeffer-Novelli, Y., Abuchahla, G.M.d.O., Cintrón-Molero, G. (eds) Brazilian Mangroves and Salt Marshes. Brazilian Marine Biodiversity . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13486-9_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13486-9_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-13485-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-13486-9

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)