Abstract

It has been documented that entrepreneurs can affect institutions at local, regional, and national levels. Most studies in entrepreneurship, however, look at how institutions and institutional frameworks support or deter entrepreneurial actions, while the literature on whether and how entrepreneurship affects institutions is lacking. This necessitates the examination of a two-way relationship between institutions and economic agents. Institutional change caused by entrepreneurs’ actions is often presented through the lens of institutional entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurs influence institutions through three main channels: political action, innovation, and direct action, which may involve “passive adaptation and evasion, active adaptation and resistance to change.” Most of the documented examples of entrepreneurs’ impact are from postsocialist countries, countries in transition, and emerging market economies. This chapter offers an extensive overview of how entrepreneurs influence institutional change in emerging market economies.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Entrepreneurship

- Institutions

- Institutional entrepreneurship

- Institutional change

- Mechanisms of institutional change

1 Introduction

The topic of entrepreneurship and institutional change has dominated the entrepreneurship literature for quite some time now. Most of the published studies have focused on how institutions and institutional frameworks provide a supportive environment for entrepreneurs or deter entrepreneurial actions in certain circumstances. For the longest time, institutions have been looked upon as a long-standing, exogenous part in a preset societal framework that remains unchanged. Economic agents and their actions, on the other hand, are limited within this framework. This very characteristic led to their significant role in the entrepreneurship literature. Very few studies have investigated the effect of entrepreneurship on institutions. While a methodical approach is still absent, it has been documented that institutions do change, and that entrepreneurs and their exploits and accomplishments induce a change in the institutional environment at local, regional, and national levels. This necessitates a step toward examining a reciprocal relationship between institutions and economic agents. Another way of explaining how entrepreneurs can impact institutions is known in the literature as institutional embeddedness.

Institutional change caused by entrepreneurs’ actions is usually presented through the lens of institutional entrepreneurship. Institutional entrepreneurs are economic agents who, acting on their own behalf, summon resources and lobby support and assistance to bring transformation into the existing institutional framework that will directly benefit them. Still, some authors argue that the role of institutional entrepreneurs may be overstated and that they may not always intend the outcome of their actions. The socio-economic and political environment sets the stage that allows entrepreneurs to bring the desired results. Entrepreneurs influence institutions through three main channels: political action, innovation, and direct action, which may involve passive adaptation and evasion, active adaptation, and resistance to change. Most of the documented examples of entrepreneurs’ impact are from postsocialist countries, countries in transition, and emerging market economies.

The rest of the chapter is structured in the following manner. Section 2 begins with a short introduction of the concepts of institutions and institutional fields, followed by a discussion on institutional change through the lens of institutional embeddedness and institutional entrepreneurship. The section ends with an overview of the interaction among institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth and how it relates to institutional change. Section 3 documents how entrepreneurs bring institutional change. It presents a summary of different categorizations of how entrepreneurs affect institutions and then examines international evidence across emerging economies for institutional change through a political process, innovations, and direct actions. Section 4 looks at entrepreneurship and institutional change in transition countries in recent years. Section 5 concludes the chapter.

2 Institutions and Institutional Change

2.1 What Are Institutions?

Early definitions of institutions focus on deep-rooted habits, customs, and traditions that developed over time and governed societal interactions (Hodgson 2006). In sociology, institutions are viewed as perceptual constructs, defined by culture, with regulative and normative components (Scott 1995). The regulative components refer to rules and regulations, and the normative components infer duty and responsibility. The emphasis on the cultural factor is very important because it forms the background for a meaningful interaction (Powell and DiMaggio 1991).

In economics, institutions are defined as the “rules of the game” that aid, but could also restrict economic actions (North 1990). Established and well-functioning institutions help lessen the risk and uncertainty in the economy and mitigate the transaction cost undertaken by economic agents. North postulates that institutions are formal and informal. Formal institutions include legal and legislative structure, while informal institutions comprise cultural norms, traditions, and values that show collective development. The interaction between institutions and economic agents outlines the institutional context and composition of the economy (North 1994).

Kalantaridis and Fletcher (2012) advance the interesting notion of institutional fields, which has only recently gained popularity in entrepreneurship. An institutional field is a well-defined and coordinated system enacting rules and regulation over economic agents who compete for access to resources, shares, and interests (Bourdieu 2005; Garud et al. 2007; Powell 2007). Kalantaridis and Fletcher argue that institutions and institutional fields differ in four aspects: theoretical origin, definitions, scope, and meaning of change. An institutional field is a mixture of institutions. The mixture creates an environment or an ecosystem where economic agents, including organizations, conduct business. One institutional field may incorporate both new and current institutions. Individual institutions may be field-specific or may operate across several institutional fields. The differentiation between institutions and institutional fields is important because of its direct link to institutional change. For institutional fields, a change may reflect a unique new combination of existing institutions that may be a part of other institutional fields. For institutions, a change involves transforming existing rules and regulations that govern economic agents’ behavior.

2.2 Institutional Change and Entrepreneurship

Most of the literature on institutions and entrepreneurship is focused on how institutions and institutional frameworks support or hinder entrepreneurs (Aldrich and Fiol 2007; Bowen and De Clercq 2008; Bruton et al. 2010; Busenitz et al. 2000; Dau and Cuervo-Cazurra 2014; El-Harbi and Anderson 2010; Estrin et al. 2013; Fuentelsaz et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2007; Mitchell and Campbell 2009; Muralidharan and Pathak 2016; Nyström 2008; Stenholm et al. 2013; Sambharya and Musteen 2014; Sobel 2008; Spencer and Gomez 2004; Stephen et al. 2005; Urbano and Alvarez 2014; Valdez and Richardson 2013; Westlund and Bolton 2003). A group of empirical studies examines how institutions affect opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship as separate constructs (Angulo-Guerrero et al. 2017; Aparicio et al. 2016; Brixiova and Egert 2017; Fuentelsaz et al. 2015; Fuentelsaz et al. 2018; Samadi 2018; Simon-Moya et al. 2013). This one-directional approach is due mainly because institutions are exogenous, stable, and social constructs (Kalantaridis and Fletcher 2012). The supposition that institutions are resistant to change has been put to the test (Bjørnskov and Foss 2016). But while a systematic theoretical treatment is still lacking, studies have documented that institutions do change, and that entrepreneurial actions bring change at both the regional and national levels (Baez and Abolafia 2002; Fuentelsaz et al. 2015; Greenwood and Suddaby 2006; Kalantaridis and Fletcher 2012; Kozul-Wright and Rayment 1997; Kuchar 2015; Yu 2001). Thus, we must allow for a two-way interaction between institutions and economic agents and between formal and informal institutions (Bjerregaard and Lauring 2012; Henrekson and Sanandaji 2011; Samadi 2018, 2019; Smallbone and Welter 2012). Informal institutions may form not only from deliberate actions but also because of changes in the formal rules and regulations. They help interpret and understand laws and legal structures. Another element of importance in the relationship between formal and informal institutions and their interaction with entrepreneurs is the system that ensures that the “rules of the game” are properly enforced (Oliver 1991). Informal institutions are governed by normative settings. Formal institutions depend on rules and regulations set by the government/state. Local and national policies determine the participation, commitment, and engagement of entrepreneurs. In a supportive environment, where informal institutions complement formal institutions, entrepreneurs thrive. In the presence of failing and inadequate formal institutions, entrepreneurs’ actions are constrained.

Illustrating the process of institutional change requires introducing two concepts: institutional embeddedness and institutional entrepreneurship. Institutional embeddedness is an attribute of institutions, referred to in the literature as the paradox of an embedded agency (Granovetter 1992; Rao 1998; Seo and Creed 2002; Sewell 1992). In the process of interaction with institutions, economic agents exert influence over institutions. Thus entrepreneurs, as economic agents, play a significant role in the institutional framework development and formation. This is related to the notion of institutional entrepreneurship (IE) introduced by DiMaggio (1988). IE outlines the actions of economic agents who use resources, seek support, and expand political capital to bring changes to the institutional framework and environment for their own benefit (Dorado 2005; Leca et al. 2008). The introduction of IE reflects a shift from the notion that institutions play a leading part in societal interactions toward accepting the role of economic agents as strategic drivers of change (Dorado 2005; Garud et al. 2007, 2013). While this shift started a new branch in the literature, some studies caution against exaggerating the capacity of individual entrepreneurs to transform institutions (Bika 2012; Lounsbury and Crumley 2007; McCarthy 2012; Smallbone and Welter 2012). Institutional changes can only happen when socio-political, cultural, economic, and other factors interact to create a proper environment (Kalantaridis and Fletcher 2012). Another potential matter with IE is the implicit assumption that entrepreneurs fully intend to bring institutional changes, while that may not always be the case (Bika 2012; Dorado 2005).

2.3 Institutions, Entrepreneurship, and Economic Growth

A separate branch of the entrepreneurship literature looks at the relationship between institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth (Acs 2006; Acs et al. 2018; Acs and Amoros 2008; Aparicio et al. 2016; Bjørnskov and Foss 2013, 2016; Wennekers and Thurik 1999; Youssef et al. 2018). While not directly related to entrepreneurship and institutional change, it derives important implications. Bjørnskov and Foss (2016), who survey the literature with a focus on empirical studies, point to several gaps linked to entrepreneurship and institutional change. They argue that the entrepreneurship literature suffers from lack of consistency when outlining institutions and institutional quality. Definitions vary from the traditional economics view in-line with North (1990) to a more comprehensive concept introduced in sociology (Kalantaridis and Fletcher 2012; Scott 1995). There is no clear distinction between formal and informal institutions on the one hand, and market and government institutions on the other (Voigt 2013). Limited studies exist on “whether the impact of entrepreneurial activity is systematically heterogenous across different institutions.” Bjørnskov and Foss contend that theoretical studies on “institutional complementarities” and how institutions interact with entrepreneurship to produce economic growth are in early stages. Likewise, they observe that very few studies provide theoretical guidelines on causality about the effect of institutions and entrepreneurship. Thus, the definition inconsistency and lack of theoretical underpinning further complicate the study of the bidirectional relationship between institutions and entrepreneurship.

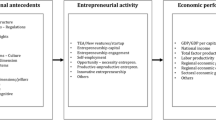

In response to Bjørnskov and Foss (2016), Acs et al. (2018) develop a theoretical model proposing that institutions and entrepreneurship work together and form what they refer to as an ecosystem that is the “missing link” in explaining economic growth. Acs et al. unite institutions and entrepreneurship in a National System of Entrepreneurship (NSE). Using data from the Global Entrepreneurship Index (Acs et al. 2014) to measure the NSE, they found that institutions and entrepreneurship act together as an ecosystem, with only marginal individual effects of institutions and entrepreneurship on economic growth. While the study does not discuss the causality issue mentioned by Bjørnskov and Foss (2016), it provides a useful theoretical framework for a further investigation.

3 How Do Entrepreneurs Bring Institutional Change?

Although entrepreneurial responses to institutions’ failure and institutional embeddedness have been studied and documented a lot recently, there is no agreement in the literature on the exact categorization of those responses (Elert and Henrekson 2014, 2016; Henrekson and Sanandaji 2011; Kuchar 2015; Oliver 1991; Troilo 2011; Welter and Smallbone 2011; Yu 2001). Most authors use as a starting point the classification of behavioral responses to an institutional framework provided by Oliver (1991). Oliver identified five such responses: “conformity or acquiescence, compromise, avoidance, defiance and manipulation.” Welter and Smallbone (2011) explain how these five categories apply to entrepreneurial behavior. While conformity and compromise signal that entrepreneurs are adapting to institutional changes; avoidance, defiance, and manipulation show nonconforming behavior. There are various degrees of nonconformity, with avoidance being considered as more of a passive and hidden reaction, and defiance and manipulation as showing an active form of challenge and resistance to institutions. Manipulation is the most involved form of entrepreneurial behavior that mounts an active attempt to change the status quo of the institutional framework.

A somewhat different classification of how entrepreneurs affect institutions is: abiding, evasion, and acting to alter the institutions (Elert and Henrekson 2014, 2016; Henrekson and Sanandaji 2011, 2012). Welter and Smallbone (2011) reconcile Elert and Henrekson’s and Henrekson and Sanandaji’s behavioral mechanisms with those proposed by Oliver. Abiding is comparable to what Oliver refers to as conformity, while altering behavior is comparable to Oliver’s manipulation category (Welter and Smallbone 2011). Evasion is aimed at weakening institutional effectiveness.

Based on their extensive studies of the former Soviet economies, Welter and Smallbone (2011) documented six behavioral responses to the institutional environment: prospecting, evasion, financial bootstrapping, diversification and portfolio entrepreneurship, networking, and personal contacts and adaptation. “Prospecting” is a term that Welter and Smallbone borrow from Peng (2000), who uses it to describe firms with innovative behavior such as new product adoption and organizational change. Welter and Smallbone caution that prospecting may not fully apply to businesses trying to survive in transition economies, because such businesses introduce changes as a strict reaction to the limitation of the institutional framework. “Financial bootstrapping,” while common for nascent entrepreneurs under different economic conditions, is especially important for entrepreneurs in transition economies. Bootstrapping is defined as a “process of finding creative ways to exploit opportunities to launch and grow businesses with the limited resources available for most start-up ventures” (Cornwall 2010). Welter and Smallbone identify serial entrepreneurship as a very successful form of bootstrapping in transition economies. “Diversification and portfolio entrepreneurship” have been recognized as a common occurrence in transition economies (Lynn 1998). Welter and Smallbone report that this is done not only to address uncertainty but also to fight corruption by staying unnoticed and keeping unnecessary attention away. “Networking and personal contacts” is another well-established strategy for most entrepreneurs. This behavior takes on a different meaning in the former Soviet economies. Ledeneva (1998, 2001), for example, describes the existence of the Soviet blat –“the widespread use of personal networks to obtain goods and services in short supply” – considered an essential part of the Soviet system. Following this, “unwritten rule” has served as successful networking to entrepreneurs against barriers to entry and dealings with government agencies. The other two responses, evasion and adaptation, are discussed later in this chapter.

Kalantaridis and Fletcher (2012) offer, by far, the most expansive and encompassing classification of what they refer to as the “processes” used by entrepreneurs to influence institutional change. Kalantaridis and Fletcher identify change through a political process, innovation, and direct action. Actions recognized under the first category are “lobbying, state capture and double entrepreneurship,” while direct actions incorporate “passive adaptation and evasion, active adaptation and resistance to change.”

In what follows, I explore the entrepreneurial responses to institutional embeddedness across emerging markets loosely based on the Kalantaridis and Fletcher (2012) categorization, together with detailed accounts.

3.1 Institutional Change Through Political Processes

Institutional change through a political process is a legislative change that affects both formal and informal rules (North 1993). One method of achieving change through the political process is “collective action” and “organization membership ” (Kalantaridis and Fletcher 2012). Smallbone and Welter (2012) present an interesting example of an unsuccessful attempt to start a change after several Central and Eastern European countries entered the European Union. In most developed countries, nongovernmental organizations and networks exist to protect the interests of entrepreneurs and small businesses and serve as a liaison with the government (Kalantaridis 2007). Forming such organizations in the postsocialist Central and Eastern European countries was difficult with limited or no previous experience with norms and customs in the functioning and governance of such entities. Thus, Smallbone and Welter report that the first attempts to set up mediating organizations who can lobby on the behalf of entrepreneurs were unsuccessful. An added challenge was the difficulty in convincing business owners to take advantage of the mediation process (Hart 2003; Kalantaridis 2007).

Another group of studies introduces the “corporate political entrepreneur” as someone who establishes strong connections with policymakers with the goal of influencing legislative decisions to the benefit of business organizations (Gao 2008; Mintrom 1997; Schneider and Teske 1992), and corporate political strategy as a form of business strategy (Gao 2006, 2008; Hillman and Hitt 1999; Schuler et al. 2002). Modifying Li et al. (2006) categorization of institutional changes instigated by corporate political entrepreneurs, Gao (2008) introduces the following four approaches as applied to China: “private lobbying, breaking an unreasonable institution in private, mobilizing social force, and taking legal action.” Private lobbying, while popular in China (Gao 2006; Hillman and Hitt 1999), has somewhat different characteristics than lobbying in Western countries (Gao 2008). For example, Gao explains that lobbying in China is done by corporate executives, informally, and in the form of gift giving. “Breaking an unreasonable institution in private,” a form of evasive entrepreneurship, is explained further in the chapter. “Mobilizing social forces” is the exposure of unfair and excessive laws and regulation to the public. Gao (2008) presents a case study of the Geely Holding Groups, whose chairman, Li Shufu, overturned the Chinese auto industry regulatory agency’s ban on the production of sedans by private companies. Li Shufu tried lobbying, unsuccessfully, before he turned to the media. According to Gao, the last strategy, legal action, is not characteristic for China, but mostly for Western countries. Citing China as an example, Ge et al. (2019) further argue that political and family ties can successfully counteract institutional voids in emerging markets, and that family ties often substitute for political ties.

Elert and Henrekson (2020) cite a similar example of a “corporate political entrepreneur” in China’s banking sector. Chinese entrepreneur, Jing Shuping, lobbied government officials to allow private ownership of banks. His campaign convinced the authorities, and in 1996, Jing Shuping founded the first mixed-ownership commercial bank, China Minsheng Banking Corp. Citing Li et al. (2006), Elert and Henrekson note that over the next 10-year period, close to 20 more banks with a comparable structure were established. Li et al. (2006) point out that such institutional changes were influenced by the extension of the other aspects of the financial markets. Liberalization of interest rates and private ownership in the automobile industry followed.

A somewhat different demonstration of institutional change through the political process is a “state capture.” State capture is an interaction between the state and businesses, observed in postsocialist economies, where newly formed firms exercise a concerted influence over the state (Hellman et al. 2003; Kalantaridis and Fletcher 2012; Yakovlev 2006; Zimmer 2004). Enterprising firm owners, known as oligarchs, use unlawful private payments to manipulate politicians, governmental officials, and administrators, to reshape the laws and regulations in a way that is beneficial to their businesses, but at a significant cost to society. Hellman et al. (2003) report that the oligarchs resort to state capture when the government “underprovides” public goods related to market entry and property rights. State capture, thus, is a channel for eliminating barriers to entry, competition, and growth in an environment where a weak and dysfunctional state cannot defy powerful “interest groups.” Yakovlev (2006) posits that in the 1990s, there were two main strategies for growing a business in Russia: state capture and “free entrepreneurship.” What determined the choice of strategy was the institutional quality, local and regional distribution of resources and possession, or lack thereof, of prior experience in business and amassed capital. Free entrepreneurship is described in the following section under passive adaptation. Further evidence of how state capture occurs is detailed in the literature on privatization of previously state-owned companies (Bortolotti and Perotti 2007; Kryshtanovskaya and White 1996; Mickiewicz 2009; Wedel 2003). Besides state capture, Hellman et al. (2003) discuss two other forms of interaction between the state and firms: influence and administrative corruption . The former occurs when firms influence the laws and regulation without private payments, while the latter is the use of small-scale bribery methods by firms to relax existing regulations. Hellman et al. point out that, contrary to state capture and influence, administrative corruption is not linked to particular advantages and gains for the firm.

The interaction between the state and firms, however, is a two-way street (Wedel 2003; Yakovlev 2006). State officials used their power and resources to lavish support on private interests. Wedel (2003) reports that in Poland, managers of formerly state-owned enterprises became the private owners of the enterprise or parts of it, while high-ranking government officials established consultant companies providing services for the departments they oversaw. The lines were further blurred with the formation of nongovernmental agencies with state resources. Kaminski (1997) points out that such convoluted interactions were deeply entrenched, with “considerable tolerance of conflict of interest.” Similar to the Polish experience, in Russia state officials privatized segments under their supervision and became private consultants for their supervised divisions (Kryshtanovskaya and White 1996). In Ukraine, the phenomenon has been documented at the regional level (Van Zon 2001, 2005; Zimmer 2004, 2007). Van Zon and Zimmer, who offer an overview of the regional development of Donbas, an industrial region in eastern Ukraine during the transition period, assert that the local economy was dominated by local organized “clans.” The clans fought to counteract external economic interests and eradicate competition, engaged in ruthless rent-seeking and sought horizontal and vertical integration of commodity chains. The clans not only colluded with the local government but also exerted significant power outside of the region trying to influence the laws and regulations at the national level (Swain 2006). Swain points out a specific example where certain areas in the region were given temporary preferential treatment by the central government to secure the local support for the state regime.

“Double entrepreneurship” is another form of interaction between the state and business owners that brings institutional change (Smallbone and Welter 2012; Yang 2002, 2007). The term, introduced by Yang (2002), explains the significant and successful expansion of entrepreneurship in China in the presence of weak and flawed institutions. During the period of economic reforms in the 1980s and 1990s, Chinese private businesses had functioned in the absence of property rights, while navigating the existing government bureaucracy (Smallbone and Welter 2012). Entrepreneurs were forced to form close connections with local officials in the form of alliances and “collective licenses ” that helped spur the growth of nonstate-owned enterprises (Chen 2007; Liang 2006). Such collusion tactics allowed newly formed companies to operate unconcerned with the ban against private business ownership. An informal banking sector has developed to help the needs of the private enterprise segment lacking financial resources and access to financial institutions (Smallbone and Welter 2012). Yang (2002) argues that entrepreneurs in China must recognize market opportunities and secure the socio-political environment to make sure that their businesses will be successful. The former is the backbone of the standard definition of an entrepreneur. The latter is a characteristic strictly associated with entrepreneurship in China, manifesting itself in the proficient use of bureaucratic rules and loopholes and manipulating them when necessary. Entrepreneurs achieve a level of bargaining power with the local authorities to broker institutional change. Smallbone and Welter (2012) thus contend that, in the context of the Chinese economic transition, institutional change is an exercise of collaboration and learning, with institutional reforms occurring after experimental entrepreneurial developments had taken place.

3.2 Change Through Innovation

Yu (2001) argues that new technologies , inventions, and breakthroughs that entrepreneurs generate help create market instabilities. The newly established realities require economic agents to adapt and navigate in an uncertain environment. Existing institutions are no longer effective because they cannot successfully manage the new environment. Thus, Yu contends, there is room for imitative entrepreneurial activities that succeed in modifying the rules and laws of markets functionality. Such a process results in creating new institutions in sync with the markets.

Along these lines, Onsongo (2019) presents an interesting case of social innovation in the financial services industry in Kenya. In 2007, Vodafone Group Plc, together with its local representative Safaricom Kenya Ltd., launched M-Pesa, a mobile phone-based platform for money transfers. The goal of M-Pesa was to service the population with no access to commercial banking. The financial services delivered by M-Pesa were unmatched in comparison with other platforms adopted globally. Vodafone and Safaricom, according to Onsongo, recognized that an unidentified institutional void existed. The multinationals took advantage of the lack of interaction between the banking and telecommunications sectors that resulted in a policy void. Thus, the case of M-Pesa is an example where multinational companies embraced the role of institutional entrepreneurs through social innovation. M-Pesa spread to many other African countries (Burns 2018). In Tanzania and Uganda, the adoption was effective because of the functional financial institutions in the former, and the high urban population density and economic freedom levels in the latter. Zimbabwe and Somalia, despite being predominantly rural countries, with no dominant mobile operator and weak banking institutions, allowed multiple network operators and achieved great success. In other countries, such as Nigeria and South Africa, the operation failed. Burns (2018) argues that the most significant component for a successful adoption of this mobile innovation is the quality of the regulatory environment.

Another example of how innovations bring institutional change is the agricultural innovation platforms (IP) in Africa (Nyikahadzoi et al. 2012; Pamuk and Van Rijn 2019; Van Paassen et al. 2014). The IP were created by partnerships, researchers, NGOs, private agents, and others. In their role of institutional entrepreneurs, the IP helped disseminate knowledge, establish learning programs and supporting networks, defend the interests of those left on the fringes, and work toward resource deployment through collective actions.

3.3 Change Through Direct Actions

3.3.1 Evasive Entrepreneurship

Evasive entrepreneurship has noticeably spurred the most extensive studies among all entrepreneurial responses to institutional embeddedness (Coyne and Leeson 2004; Elert and Henrekson 2014, 2016, 2017; Elert et al. 2016; Kalantaridis et al. 2008; Smallbone and Welter 2012; Yakovlev 2006). Evasive entrepreneurs bypass the existing institutions by exploring loopholes and inconsistencies in existing laws (Coyne and Leeson 2004; Elert and Henrekson 2016). When institutions are inefficient, entrepreneurs use innovations to take advantage of business opportunities resorting to evasive activities, and in the process, extract rent (Elert and Henrekson 2017; Leeson and Boettke 2009). While many cases of entrepreneurs demonstrating evasive behavior have been documented, Elert and Henrekson (2017) point out they are all disruptive innovators who upset the existing institutional framework. Thus, an evasive activity counts as evasive entrepreneurship only if it brings disruptive innovation .

The size of the informal economy in a country has often been connected to the level of evasive entrepreneurship (Boettke and Coyne 2003). Developing countries have been reported to have large informal sectors (Schneider 2003, 2005; Schneider and Enste 2000, 2002). The size of the informal economy is strongly related to the level of labor market regulations, corruption, and overall quality of institutions in the country (Antunes and Cavalcanti 2007; Ulyssea 2010). In Elert and Henrekson (2017), the “institutional contradictions and voids” that exist in a country encourage evasive entrepreneurship. Prior research on institutional voids has established that aside from the “institutional vacuum” experienced by Eastern European countries in transition (Ledeneva 2001; Stark 1998; Stark and Bruszt 1998; Yakovlev 2006), institutional voids obstruct markets development, functioning, and participation (Bourdieu 2004; Khanna and Palepu 2000; Mair and Marti 2009; Woodruff 1999).

Mair and Marti (2009) argue that institutional voids that interfere with market participation create opportunities for “motivated” entrepreneurs. The authors examine the activities of BRAC, an NGO in Bangladesh. BRAC’s main goal is to alleviate poverty. Through a specially designed program, titled Challenging the Frontiers of Poverty Reduction, BRAC aimed to reach poor women living in rural areas with extreme poverty and no access to microfinance. The goal is to help the poor get involved in the market. BRAC’s help is channeled through four components: “special investment, employment and enterprise development training, social development and essential health care.” The special investment program intents to create a stock of physical capital that the poor can use in livestock rearing, vegetable cultivation, and other farm and nonfarm activities. The enterprise development training aims at building basic financial literacy and assets that will qualify the poor for microfinance programs. The last two components improve the community structure and connections and provide health care services. Through a process of entrepreneurial bricolage BRAC combined internal resources such as knowledge, previous experience, established networks, and external resources such as current procedures for microfinancing and religious beliefs. Mair and Marti find that Bangladesh is uniquely suited for studying institutional entrepreneurship and bricolage in a resource constrained environment. While abundant in informal institutions, the country lacks market-oriented institutions. The study finds that bricolage is inherently political in nature and may have some unintended consequences. The latter is reflected in the decision to abandon most adopted microfinance practices when rolling out the new program. This was done because women living in poor rural areas face certain institutional constraints. Another example of negative outcomes is the decline of older attitudes and values and the formation of new ones. With the poor working in rural Bangladesh, this is the effort to “break relations of dependence between the elites and the poor.”

Over the past decade, educational entrepreneurs in South Sudan built schools with little to no resources or government involvement (Longfield 2015). Local community members, via grass-root initiatives, helped improve the access to schooling for those living in extreme poverty. Longfield documented many cases of former and current teachers, a police officer, and other ordinary people who started schools in huts and mud-walled rooms in Juba, the capital of South Sudan. Adding one class at a time and increasing the class sizes gradually, they answered local needs. In developing countries strapped for resources, this informal approach of promoting educational development is bound to be much more effective than a full-scale national system.

Evasive entrepreneurship is very much in-line with Baumol (1990)‘s productive and unproductive entrepreneurship classification. When an entrepreneurial activity exists only because of evasive entrepreneurial behavior, it may be productive (Elert and Henrekson 2014). On the other hand, theft, bribes, extortion, tax evasion, smuggling, etc., are unproductive forms of entrepreneurial behavior. Along these lines, Elert and Henrekson (2014) document evasive entrepreneurial activities with the corresponding economic institutions, entrepreneur types, and an assigned productive vs unproductive designation. The institutions they consider are: “tax code, employment-protection legislation, competition policy, capital market regulation, trade policy, enforcement of contracts, and law and order/property rights.” For example, tax avoidance and tax evasion are listed under tax code, the former as a productive and the latter as an unproductive activity, with tax consultants in the role of entrepreneurs. The authors conclude that the short-run effects of evasive entrepreneurship on economic growth are related to the activity it aids. “If it enables the reallocation of resources to the pursuit of profitable business activities, it may well be socially productive. But, if it enables lobbying, rent-seeking, or risk-obscuring, it may cause a negative shift in the PPF.”

The above discussion on productive versus unproductive evasive entrepreneurship is linked to the dialogue on entrepreneurship, institutions, and economic growth introduced in Sect. 2.3. Recent studies related the idea that entrepreneurship and institutions form an “ecosystem” that may explain cross-country differences in economic growth (Acs et al. 2018). Elert and Henrekson (2014) point out that studies such as Gennaioli et al. (2013), who report that institutions cannot explain within-countries cross-regional differences, suggest that evasive entrepreneurship may be a substitute, albeit imperfect, for inefficient institutions.

The crucial question is: How do evasive entrepreneurs affect institutional change in the long run? With their discussion on the different evasive entrepreneurial activities, Elert and Henrekson (2014, 2017) argue that the effect of evasive entrepreneurship on institutions is indirect because it modifies the “de facto effect of institutions.” Elert and Henrekson give examples where evasive entrepreneurs cause institutions to lose their importance and role in society over time, motivate new laws and regulations, offer help and direction when institutional improvements may be ambiguous, and ultimately alter existing institutions. Long-term effects are very much determined by the path and extent of the change.

Drawing on Lu (1994) and Li et al. (2006), Elert and Henrekson (2014) relate several historical accounts of the effect of evasive entrepreneurship on institutions in China. In the late 1970s, destitute farmers from the eastern province Anhui divided the village land among the families living in the area and let each family work their piece of land by themselves. Such an act ran against state policy and evaded the official central government collectivization mandate. Even with the support of the local authorities, the farmers still faced prison. The reform proved very successful when bountiful crops were collected during the following year. What’s more important is that it brought about China’s agricultural reform. In another instance, the Chinese government introduced a policy in the early 1980s allowing private companies with a few employees to exist. The policy, meant to be very restrictive, was largely defied. In response, the government made institutional changes allowing the new companies. Both examples of evasive entrepreneurship behavior resulted in reforms that loosened institutional regulations. On the opposite side of the spectrum, the Communist Revolution in 1949 brought about changes in the way business operated with significant state and local restrictions. Administrators and bureaucrats exploited the newfound opportunities for extracting rent. The widespread corruption and misuse of state resources for personal gains that ensued was addressed by instituting collectivization and nationalization, thus “tightening” the existing institutions.

A more recent example of evasive entrepreneurship is the Chinese Shan-Zhai mobile phone sector (Lee and Hung 2014). Shan-Zhai phones started in the late 1990s as low-cost imitations distributed informally, via stolen good markets. While considered illegal, they were popular among the most economically disadvantaged. Shan-Zhai entrepreneurs aggressively sought to contend the state-licensed national companies. They actively challenged the restriction of competition in the phone sector. A decade later, the sector gained a significant advantage as a model of innovation. In 2007, the Chinese government removed the license control of mobile phones and officially acknowledged Shan-Zhai.

3.3.2 Passive Adaptation

As mentioned in the previous chapter, “free entrepreneurship,” “distancing from the state,” or “exit” was one of the two main strategies for growing a business in the 1990s Russia (Yakovlev 2006). Yakovlev reports that such a strategy was chosen by younger and/or smaller companies operating predominantly in the service and trade industries. These companies did not have the political and business capital necessary to establish connections with the elite and influence the institutional framework in any meaningful way. They were doing well when the local and regional authorities could make provisions and support local business growth. Such occurrences were observed in large cities or areas rich in natural resources.

A somewhat different approach is described in Kalantaridis et al. (2008), who undertook a fieldwork study of the global integration of the clothing industry in Transcarpathia , a region in Western Ukraine, during the postsocialist period. The authors emphasize that the clothing industry adapted to the realities of the new political environment by developing a network of connections and effective relationships through “asymmetrical power and mutual dependence.” Thus, instead of challenging the existing power arrangement, agents focused on engaging and developing competencies by lower-level participants. Kalantaridis et al. argue that in the long run, such a strategy helps to deal with the increased levels of political and economic uncertainty.

Smallbone et al. (2010) present another example of a passive adaptation in Ukraine where the service industry experienced a significant growth and expansion at the very beginning of the transition period. Newly established firms increasingly turned to small business consulting companies for a wide range of services. But instead of hiring several specialized companies, most firms found it advantageous to work with one consulting company that could deliver all the services needed. The business consulting sector was populated by very successful and well-established companies. The success of the consulting service industry demonstrates how entrepreneurs find institutional voids and devise solutions that could bring potential institutional changes (Smallbone and Welter 2012).

In an empirical study on institutions and entrepreneurship in Middle Eastern and North African countries, Samadi (2018) shows that passive adaptation and institutions-abiding entrepreneurship may bring institutional change. After looking at the individual effects of opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship on institutional change in a bidirectional setup, the author concludes that the former influences institutional change in the short run. As Elert and Henrekson (2020) argue, Samadi’s finding confirms Holcombe’s (1998) statement that when productive entrepreneurs exploit and seize opportunities, they create new prospects for other entrepreneurs to explore. This domino effect resonates not only with the level of economic development but also the quality and advancement of formal and informal institutions (Coyne et al. 2010).

3.3.3 Active Adaptation and Resistance to Change

Kalantaridis and Fletcher (2012) report on two interesting cases of active entrepreneurial adaptation, documented in the literature, which occurred in North Korea and Russia. In the 1990s, North Korea experienced one of the worst famines known to humankind, with close to one million people reportedly dying of hunger (Haggard and Noland 2007, 2010, 2011). Haggard and Noland, the two leading scholars on the 1990s famine, surveyed North Korean refugees who escaped the country. The authors found that failed distribution channels and socialist entitlements, coupled with unsuccessful agricultural policies, played a significant role. The population was forced to find creative ways to survive. In their attempts to find food, people resorted to different market activities that pushed the economy to “marketize” despite the effort of the state to counteract any market-oriented behavior. Postsocialist Russia experienced the establishment of “agro-holdings” and large-scale, vertically integrated farming operations with significant economies of scale (Grouiez 2018; Rylko and Jolly 2005; Voigt and Wolz 2014). The agro-holdings were independently registered, owned, and managed externally, with tight connections to public institutions. Wegren (2004) argues that they resulted from the agrarian reform which brought private property legalization, distribution of farmland among people working on large farms, and privatization of state-owned enterprises. Resistance to change among the population, on the one hand, and the formerly state-owned enterprises, on the other, led to the formation of the operators. As Haggard and Noland state, the operators could ease certain human and capital limits and institutional deficiencies.

Kalantaridis and Fletcher (2012) cite two examples of resistance to institutional change. The first example refers to the land reforms aimed at redistributing land ownership in Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s (De Janvry and Sadoulet 1989). Reforms were unsuccessful because large landowners, in their attempt to resist the changes, entered into agreements with the state to modernize their farms and, in return, avoid land confiscation. The second example has to do with peasant resistance (Scott 1985). Scott relates two cases of peasant resistance in a Malaysian rice-farming village in the late 1970s: A group of women boycotted landowners who had hired farm equipment to replace manual workers and stem unidentified thefts of harvested crops. Additional forms of “everyday resistance” are noncompliance, neglect, boycott, fake ignorance, intentional damage, and aggressive and violent behavior. Scott’s concepts are further applied by Colburn (1989) in a study of peasant resistance of seven other countries.

3.4 Other Mechanisms to Influence Institutional Change

3.4.1 Path-Dependency

Welter and Smallbone (2011) and Smallbone and Welter (2009) identified “path-dependent behavior” as another mechanism for influencing institutional change. Path-dependency reflects evolutionary patterns of behavior adopted in the past that, in the context of Welter and Smallbone’s studies, refer to socialist legacy and traditions.

Studies of the transition of path-dependent economies in Central Europe, post-Soviet, and Asian countries found that path-dependency only prolongs the period of transition while keeping the old cultural norms alive and well (Chavance 2008; Chavance and Magnin 2002). The phenomenon is reflected in the trajectories of the countries and their experience with formal and informal institutional change. This is caused by the “inertial character” of informal institutions that results from their being rooted in cultural heritage (North 1990). North argues further that changes in informal institutions will lag behind changes in formal institutions because of that very cultural component. It has been recognized that path-dependency may have positive effects (Chavance 2008).

Stark and Bruszt (1998) present case studies from East Germany, Hungary, and the Czech Republic and show how each country took a different path during the transition period from Socialism toward a market-oriented economy that shaped their institutional frameworks. The authors argue that no single transition path applies to all Central European countries, but that several pathways, deep-rooted in the historical, cultural, and social background of each individual country, exist. They refer to the period of transition as a process of transformation that comprises “rearrangements, reconfigurations and re-combinations.” For example, Stark and Bruszt show that different tactics are used across the three countries to “recombine” property and political rights.

Ledeneva (2001) provides an extensive overview of the unwritten rules in Russia: what they are, how they work, and how and why they have survived. The author states that “the problem is not the existence of informal practices or institutions per se, but their indispensability for bridging the gaps in the formal framework” (Ledeneva 2001, p. 40). Ledeneva argues that when some of these rules, as well the informal institutions they relate to, are unnecessary, they will cease to exist. Similar accounts are provided by Welter and Smallbone (2008) for women entrepreneurs in Uzbekistan and by Welter and Smallbone (2003) for Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, and the Russian Federation.

A different account of path-dependency is offered in Geertz (1963). Geertz, a cultural anthropologist, studied the economic development of two Indonesian towns during the 1950s. In Modjokuto, a town on the island of Java, entrepreneurs struggled to move away from a bazaar-type economy to a “firm-oriented” modern system with small stores and factories. Geertz found that what entrepreneurs lack is not capital, opportunities, resources, or drive. “They lack the capacity to form efficient economic institutions; they are entrepreneurs without enterprises.” In the bazaar economy, governed by ancient conventions of trade, interactions were reduced to separate person-to-person dealings. Three mechanisms kept the system in place. A “sliding price system” where prices were mere estimates was complemented by constant haggling. An intricate arrangement of credit exchanges guaranteed that credit balances were maintained at minimal levels. Spreading efforts across many transactions provided a good form of risk management. While the system could occupy a considerable amount of people, it provided no incentives for established businessmen. The absence of any form of market institutions prevented such entrepreneurs from exploring new forms of production, new resources, sources of profits, etc. The economic reform was inhibited by two factors: the bazaar traditions and the rising postwar urbanization. The emerging middle class of store and factory owners was in a stark contrast with the traditional bazaar traders. New political alliances were formed. Geertz notes that all changes were “the results of fundamental alterations in cultural beliefs, attitudes, and values.”

In Tabanan, a city on the island of Bali, Geertz observed a rural economy settled by farmers and controlled by communal traditions. People on the island did almost all of their daily activities in groups. The social structure was dominated by different types of economic groups, each one devoted to a specific task, with no overlapping. Commoners and aristocracy were integral parts of society. Local entrepreneurs, most of whom were exiled nobles, tried to change the agrarian economy by introducing a firm-type structure. One of the first modern economic formations, founded and managed by nobles, was “The People’s Trade Association of Tabanan.” The association raised money by selling shares to local residents and other aristocrats. Its goals were to oversee the local import and export, launch more incorporated companies, and build a store, a warehouse, and an office building. A smaller, but similar in structure and economic activities, company appeared soon afterward. While the local entrepreneurs spearheading the two cities’ economic transformation were successful in the beginning, they soon found that readjusting old customs would not work as planned. Geertz states that complete rebuilding of informal institutions, such as attitudes, beliefs, and values, is necessary.

3.4.2 Institutional Acculturation

Institutional acculturation is used in a study of diaspora entrepreneurship in Nepal (Riddle and Brinkerhoff 2011). The authors define institutional acculturation as the exposure of diaspora entrepreneurs to the institutional framework in their adopted countries and argue that such entrepreneurs bring that experience back to their native countries and help change and improve the institutions there. Riddle and Brinkerhoff present the case of Thamel.com, a web portal for sending goods, services, money transfers, etc., to Nepal. The portal was founded by Bal Joshi who studied in the USA and returned to Nepal afterward. Bal Joshi found that the services of Thamel.com were mostly used by migrant entrepreneurs to help their families and friends back home. According to Riddle and Brinkerhoff, the new company, influenced Nepal’s regulation concerning the active role of the government in creating a functional and supportive business environment, helped form new consumer expectations regarding the goods and services businesses offer and their customer-support orientation, and rules about family duty and inter-caste social interaction.

Saxenian (2002) presents examples of institutional acculturation in Taiwan, India, and China. All three cases are related to the formation and growth of “transnational communities” and “global production networks.” In Taiwan, Saxenian examined the role of Miin Wu who emigrated to the USA in the early 1970s. After receiving a doctoral degree in electrical engineering from Stanford University, Wu held senior positions at several semiconductor companies based in Silicon Valley. In the late 1980s, Wu returned to Taiwan where he established his own company, Macronix Co. In 1996, Macronix Co became the first Taiwanese company listed on NASDAQ. Close to 3000 Taiwanese engineers returned home in the 1980s after studying and working in the USA. By the late 1990s, the Hsinchu Science Park, where Macronix Co was located, became the hub of 284 companies, 40% of them founded by US-trained engineers. The government responded by investing heavily in building supporting infrastructure and a well-functioning venture capital industry. The transfer of knowledge, capital, and contacts that occurred within a short space of time spurred innovation and cemented Taiwan’s role as a leader in producing personal computers and semiconductors.

Institutional acculturation in India developed at a slightly different pace. In the 1990s, Indian professionals working and living in the USA founded two associations – the Indus Entrepreneur (TiE) and the Silicon Valley Indian Professionals Association (SIPA). As Silicon Valley companies began setting up branches in India, the Indus Entrepreneur formed chapters in several large cities such as Bangalore, Bombay, Delhi, Hyderabad, and Calcutta. IT entrepreneurs in India established partnerships with US-based counterparts. Despite the success, few US-educated engineers returned to India. Saxenian (2002) argues that US-based IT entrepreneurs exerted a significant influence over government policy in India. In 1999, the Indian Securities and Exchange Board formed a committee headed by US-based entrepreneur K.B. Chandrasekhar. The committee was tasked with proposing institutional reforms in the venture capital industry. Other US-based Indian entrepreneurs took part in the discussion on deregulating the telecommunications industry.

The Chinese institutional acculturation case is comparable to the Taiwanese experience. Significant number of US-educated Chinese professionals began returning home in the early to mid-1990s. Citing the China Research Center and the US International Education Association, Saxenian (2002) reports that 30,000 US-educated Chinese professionals returned home between 1978 and 1998. A more recent evidence presented by the Beijing Science & Technology Committee shows that 140,000 Chinese students returned to China between 1996 and 2000, and that 3000 of them started new companies (Saxenian 2002). Responding to the significant wave of returnees, the government reacted by promoting exchange and encouraging return entrepreneurship. Chinese-based policymakers, universities, and IT companies increased their level of interaction with US-based Chinese companies. The Ministry of Education created a program to enable Chinese nationals working and living abroad to take part in technology-related conferences and projects. Government officials, both at the local and central levels, began actively recruiting Chinese technology professionals living abroad. Local governments established venture parks offering infrastructure, financial support, and other benefits. Saxenian (2002) points out that the Chinese government policies were similar to the policies used by the Taiwanese government in the 1970s and 1980s.

4 Entrepreneurship and Institutional Change in Transition Countries in Recent Years

Transition countries are countries undergoing a transformation from a centralized to a market economy (Feige 1994). Since the theoretical foundation of entrepreneurship is based on market economies in developed countries, a dedicated field investigating entrepreneurship in a transition environment has developed over the past 20 years (Arnis and Chepurenko 2017; Gao 2008; Kshetri 2009; McMillan and Woodruff 2002; Parsyak and Zhuravlyova 2001; Peng 2000; Smallbone and Welter 2001, 2009, 2012; Welter and Smallbone 2014; Smallbone et al. 2010; Wedel 2003; Welter and Smallbone 2003, 2008, 2011; Yang 2002). Welter and Smallbone (2014) point out that while entrepreneurship in transition economies has unique characteristics rooted in their heritage, key observations and outcomes are crucial for the theory. They argue that the field is moving “towards the mainstream.”

Each country has a distinct path of transition that reflects the interaction between entrepreneurial actions and the institutional, social, and political environment (Arnis and Chepurenko 2017; Welter and Smallbone 2014). This interaction that develops and changes over time has been the focus of most recent studies in entrepreneurship in transition economies. Studies generally fit in two categories: cross-country comparative analysis (Buterin et al. 2017; Delener et al. 2017; Ghura et al. 2019; Krasniqi and Desai 2017; Lechman 2017; Szerb and Trumbull 2016; Van der Zwan et al. 2011) and country-specific assessment (Bzhalava et al. 2017; Chavdarova 2017; Chepurenko et al. 2017; Isakova 2017; Krumina and Paalzow 2017; Lauzikas and Miliute 2017; Lukes 2017; Mets 2017; Marozau and Guerrero 2016; Pilkova and Holienka 2017; Pobol and Slonimska 2017; Rebernik and Hojnik 2017; Ruminski 2017; Williams et al. 2017; Williams and Vorley 2017; Xheneti 2016). The emphasis in both is predominantly one directional: from institutional environment to entrepreneurial development, with the rare mention of a possible bidirectional relationship.

Two recent cross-country studies (Szerb et al. 2017; Szerb and Trumbull 2016; Van der Zwan et al. 2011) compared the level of entrepreneurship development between transition and nontransition in European countries. Szerb and Trumbull used a sample of 83 countries, with 15 post-Soviet and Central and Easter European (CEE) countries in transition among them, and data from the Global Entrepreneurship Development Index. They found that while there were variations between the two groups, they were alike in their attitudes toward entrepreneurship. Looking at this result from entrepreneurial perception viewpoint, Aidis (2017) argues that institutional changes will stem from the growing levels of entrepreneurial involvement. In Szerb and Trumbull’s study, Russia was the only country where both parameters fell behind those in all other countries in the sample. Van der Zwan et al. (2011) used data from the Flash Eurobarometer Survey on Entrepreneurship and a sample of 11 transition and 25 nontransition countries in Europe and Asia to compare entrepreneurial involvement. The authors found that while transition countries are doing better than nontransition countries in terms of entrepreneurship levels, administrative rules and regulations are perceived as an impediment more in countries in transition than in nontransition countries.

In a regional-level analysis, Lazlo et al. (2017) investigate the entrepreneurial performance of CEE countries between 2007 and 2011 and find that it lags behind the rest of Europe. While CEE countries are doing well on “entrepreneurial aspirations,” they falter on “entrepreneurial attitudes.” The authors recommend that country specific, grounded in a local context, policies should be adopted. Krasniqi and Desai (2017) take a slightly different direction by examining how institutions affect export-oriented entrepreneurial firms in 26 transition countries from 1998 to 2009. They find that formal institutions have no effect, but stronger informal institutions advance export performance. In a similar fashion, Lechman (2017) investigates technology-driven export and firm internationalization in a sample of seven CEE countries between 1995 and 2015. Lechman argues that while technology-driven exports boost trade flows, structural and institutional changes in transition economies with strong global alignment may be less effective. For a few more recent examples on the effect of institutions on entrepreneurship in transition economies, see Buterin et al. (2017), Delener et al. (2017), and Ghura et al. (2019).

Numerous studies explore entrepreneurship and institutional development in a country-specific context. Probably the most important knowledge addition to the field is the recently documented evidence that transition countries take divergent paths. Some countries, such as Poland (Ruminski 2017), Lithuania (Lauzikas and Miliute 2017), and Slovakia (Pilkova and Holienka 2017), show rapid progress of entrepreneurship and supporting legal environment. Other countries, such as Albania (Xheneti 2016), Kosovo (Williams and Vorley 2017), Montenegro (Williams et al. 2017), and Russia (Chepurenko et al. 2017), are either in early stages or experience unresolved, and in some cases uncertain, socio-economic, and political conditions.

Poland is considered one of the most successful CEE transition countries (Ruminski 2017). Entrepreneurship played a substantial role in the country’s fast economic development over the past 25 years. Ruminski cautions, however, that while entrepreneurship surpasses the average European Union (EU) levels in some aspects, it leaves a lot to be desired in others. For example, the economy is plagued with restrictive labor market regulations, a convoluted legal system, and inefficient public administration institutions. Uncertainty in the political environment and viability of recent economic reforms slowed down the wave of foreign direct investments. On the positive side, government initiatives such as economic zones, centers for innovations, incubators, and technology parks have helped alleviate some of the issues mentioned above. Likewise, the early EU-membership of the three Baltic countries, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, has spurred productive entrepreneurship and launched all three countries on the path of successful economic development (Aidis 2017). In Estonia, political entrepreneurship on the part of the government was responsible for the high rates of technology entrepreneurship in the country (Mets 2017). Krumina and Paalzow (2017) argue that in Latvia necessity-driven entrepreneurship helped the economy during downturns.

Lauzikas and Miliute (2017) take a somewhat different perspective on entrepreneurship in Lithuania by concentrating on the role of education. They find that educational programs need to be updated with new topics such as risk management and strategic planning, and that innovation and creativity should be promoted and stimulated in schools. The authors stress that such investigations, while lacking, are essential during periods of adaptation of the national education system. Likewise, Bzhalava et al. (2017) report that any level of business-oriented education is significantly and positively correlated with opportunity entrepreneurship in Georgia. For a similar analysis on the effect of education see Marozau and Guerrero (2016) for the case of Belarusian higher education institutions and Lukes (2017) for entrepreneurship education and research in academia in the Czech Republic.

Rebernik and Hojnik (2017) and Pilkova and Holienka (2017) examine the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Slovenia and Slovakia, respectively. The authors found evidence of nontransparent institutions, administrative burden, inadequate entrepreneurship education, and government support. In Ukraine, entrepreneurship often fails to realize the potential of cooperation between small and large enterprises (Isakova 2017). Main reasons for the lack of cooperation are insufficient business infrastructure and legal environment, as well as lack of business expertise. Chepurenko et al. (2017) offer a regional perspective on opportunity-driven entrepreneurship in Russia. They found statistically significant regional differences in the level of opportunity-driven early entrepreneurship. The authors suggest that local governments should develop policies to address entrepreneurial motivation in less dynamic regions. Finally, an interesting example of how entrepreneurs affect informal institutions is network entrepreneurs in Bulgaria (Chavdarova 2017). The author examines how strategic networks are formed from dual agreements with employees, nepotism, and ties with informal workers. “Network entrepreneurs build markets from networks.” Their methods have become recognized informal institutions used for labor market adjustments.

5 Conclusion

The account of the interaction between entrepreneurship and institutions provided here signifies that a “bidirectional” relationship exists between the two. Yet, it is surprising that the topic has not been studied more completely in the theoretical literature. No systematic theory exists to address the causality issue toward whether and how entrepreneurs affect institutions. A lot of empirical evidence has accumulated over the years. This is especially true for the period after 1990 when many countries in Eastern and Central Europe adopted the path of transition from central planning toward a market economy. Most of the documented examples of entrepreneurs’ impact are from postsocialist countries, countries in transition, and emerging market economies. The extant empirical studies are country-specific, with a lot of anecdotal reporting. The effect of entrepreneurship on institutions is related through the lens of political process, innovation, and direct action. Institutional change through a political process is a legislative change in formal and informal institutions. The forms of political process examined here are “collective action” and “organization membership,” “corporate political entrepreneurship” and lobbying, and “state capture” and “double entrepreneurship.” Change through innovation develops when new technologies and breakthroughs create market uncertainties that require a new institutional framework. Entrepreneurs’ direct actions are categorized into evasive entrepreneurship, passive adaptation, active adaptation, and resistance to change. Two other mechanisms to influence institutional change are discussed, path-dependency and institutional acculturation. Path-dependency reflects evolutionary patterns of behavior, such as traditions, customs, and values. Institutional acculturation is generally understood in the context of diaspora entrepreneurs, who bring the experience from the adopted countries to their native countries. While some channels through which entrepreneurs affect institutions are well documented, such as evasion for example, others, such as innovation are less well understood. There are lessons that can be learned on how influencing institutions and the institutional environment in emerging economies may stimulate economic growth.

References

Acs, Z. (2006). How is entrepreneurship good for economic growth? Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 1, 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1162/itgg.2006.1.1.97.

Acs, Z. J., & Amoros, J. E. (2008). Entrepreneurship and competitiveness dynamics in Latin America. Small Business Economics, 31(3), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9133-y.

Acs, Z. J., Autio, E., & Szerb, L. (2014). National systems of entrepreneurship: Measurement issues and policy implications. Research Policy, 43(3), 476–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.08.016.

Acs, Z. J., Estrin, S., Mickiewicz, T., & Szerb, L. (2018). Entrepreneurship, institutional economics, and economic growth: An ecosystem perspective. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 501–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0013-9.

Aidis, R. (2017). Staying in the family: The impact of institutions and mental models on entrepreneurship development in post-soviet transition countries. In S. Arnis & A. Chepurenko (Eds.), Entrepreneurship in transition economies: Diversity, trends, and perspectives (pp. 15–32). Berlin\Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57342-7_2.

Aldrich, H. E., & Fiol, C. M. (2007). Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. In Á. Cuervo, D. Ribeiro, & S. Roig (Eds.), Entrepreneurship (pp. 105–127). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-48543-8_5.

Angulo-Guerrero, M.-J., Perez-Moreno, S., & Abad-Guerrero, I.-M. (2017). How economic freedom affect opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship in the OECD countries. Journal of Business Research, 73, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.11.017.

Antunes, A., & Cavalcanti, T. V. (2007). Startup costs, limited enforcement, and the hidden economy. European Economic Review, 51(1), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2005.11.008.

Aparicio, S., Urbano, D., & Audretsch, D. (2016). Institutional factors, opportunity entrepreneurship and economic growth: Panel data evidence. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 102, 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.04.006.

Arnis, S., & Chepurenko, A. (Eds.). (2017). Entrepreneurship in transition economies: Diversity, trends, and perspectives. Berlin\Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/2F978-3-319-57342-7.

Baez, B., & Abolafia, M. Y. (2002). Bureaucratic entrepreneurship and institutional change: A sense-making approach. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 12(4), 525–552. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a003546.

Baumol, W. (1990). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5, Part 1), 893–921. https://doi.org/10.1086/261712.

Bika, Z. (2012). Entrepreneurial sons, patriarchy and the colonels’ experiment in Thessaly, rural Greece. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 24(3–4), 235–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2012.670915.

Bjerregaard, T., & Lauring, J. (2012). Entrepreneurship as institutional change: Strategies of bridging institutional contradictions. European Management Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-4762.2012.01026.x.

Bjørnskov, C., & Foss, N. (2013). How strategic entrepreneurship and the institutional context drive economic growth. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 7(1), 50–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1148.

Bjørnskov, C., & Foss, N. J. (2016). Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth: What do we know and what do we still need to know? Academy of Management Perspectives, 30(3), 292–315. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2015.0135.

Boettke, P. J., & Coyne, C. J. (2003). Entrepreneurship and development: Cause or consequence? Advances in Austrian Economics, 6, 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1529-2134(03)06005-8.

Bortolotti, B., & Perotti, E. (2007). From government to regulatory governance: Privatization and the residual role of the state. The World Bank Research Observer, 22(1), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkl006.

Bourdieu, P. (2004). Acts of resistance: Against the new myths of our time (1st ed.). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. (2005). The social structures of the economy. Cambridge. In UK. Malden, MA: Polity.

Bowen, H. P., & De Clercq, D. (2008). Institutional context and the allocation of entrepreneurial effort. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(4), 747–767. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400343.

Brixiova, Z., & Egert, B. (2017). Entrepreneurship, institutions and skills in low-income countries. Economic Modelling, 67, 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2017.02.020.

Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H.-L. (2010). Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: Where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3), 421–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00390.x.

Burns, S. (2018). M-Pesa and the ‘market-led’ approach to financial inclusion. Economic Affairs, 38(3), 406–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecaf.12321.

Busenitz, L. W., Gómez, C., & Spencer, W. J. (2000). Country institutional profiles: Unlocking entrepreneurial phenomena. The Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 994–1003. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556423.

Buterin, V., Skare, M., & Buterin, D. (2017). Macroeconomic model of institutional reforms’ influence on economic growth of the new EU members and the Republic of Croatia. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 30(1), 1572–1593. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2017.1355260.

Bzhalava, L., Jvarsheishvili, G., Brekashvili, P., & Lezhava, B. (2017). Entrepreneurial intentions and initiatives in Georgia. In S. Arnis & A. Chepurenko (Eds.), Entrepreneurship in transition economies: Diversity, trends, and perspectives (pp. 261–278). Berlin\Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57342-7_15.

Chavance, B. (2008). Formal and informal institutional change: The experience of post-socialist transformation. The European Journal of Comparative Economics, 5(1), 57–71.

Chavance, B., & Magnin, E. (2002). Emergence of path-dependent mixed economies in Central Europe. In G. Hodgson (Ed.), A modern reader in institutional and evolutionary economics (pp. 168–200). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Chavdarova, T. (2017). The network entrepreneur in small businesses: The Bulgarian case. In S. Arnis & A. Chepurenko (Eds.), Entrepreneurship in transition economies: Diversity, trends, and perspectives (pp. 243–258). Berlin\Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57342-7_14.

Chen, W. (2007). Does the color of the cat matter? The red hat strategy in China’s private enterprises. Management and Organization Review, 3(1), 55–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2007.00059.x.

Chepurenko, A., Popovskaya, E., & Obraztsova, O. (2017). Cross-regional variations in the motivation of early-stage entrepreneurial activity in Russia: Determining factors. In S. Arnis & A. Chepurenko (Eds.), Entrepreneurship in transition economies: Diversity, trends, and perspectives (pp. 315–342). Berlin\Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57342-7_18.

Colburn, F. D. (Ed.). (1989). Everyday forms of peasant resistance. Armonk: Sharpe.

Cornwall, J. (2010). Bootstrapping. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Coyne, C., & Leeson, P. (2004). The plight of underdeveloped countries. Cato Journal, 24(3), 235–249.

Coyne, C. J., Sobel, R. S., & Dove, J. A. (2010). The non-productive entrepreneurial process. The Review of Austrian Economics, 23(4), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-010-0124-2.

Dau, L. A., & Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2014). To formalize or not to formalize: Entrepreneurship and pro-market institutions. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(5), 668–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.05.002.

De Janvry, A., & Sadoulet, E. (1989). A study in resistance to institutional change: The lost game of Latin American land reform. World Development, 17(9), 1397–1407. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(89)90081-8.

Delener, N., Farooq, O., & Bakhadirov, M. (2017). Is innovation a determinant for SME performance? Cross-country analysis of the economies of former USSR countries. In S. Arnis & A. Chepurenko (Eds.), Entrepreneurship in transition economies: Diversity, trends, and perspectives (pp. 97–111). Berlin\Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57342-7_6.

DiMaggio, P. (1988). Interest and agency in institutional theory. In L. G. Zucker (Ed.), Research on institutional patterns: Environment and culture. Cambridge: Ballinger Publishing.

Dorado, S. (2005). Institutional entrepreneurship, partaking, and convening. Organization Studies, 26(3), 385–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605050873.

Elert, N., & Henrekson, M. (2014). Evasive entrepreneurship and institutional change. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2513475.

Elert, N., & Henrekson, M. (2016). Evasive entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 47(1), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9725-x.

Elert, N., & Henrekson, M. (2017). Entrepreneurship and institutions: A bidirectional relationship. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 13(3), 191–263. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000073.

Elert, N., & Henrekson, M. (2020). Entrepreneurship prompts institutional change in developing economies (IFN Working Paper No. 1313). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3512819

Elert, N., Henrekson, M., & Wernberg, J. (2016). Two sides to the evasion: The Pirate Bay and the interdependencies of evasive entrepreneurship. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 5(2), 176–200. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEPP-01-2016-0001.

El-Harbi, S., & Anderson, A. R. (2010). Institutions and the shaping of different forms of entrepreneurship. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 39(3), 436–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2010.02.011.

Estrin, S., Korosteleva, J., & Mickiewicz, T. (2013). Which institutions encourage entrepreneurial growth aspirations? Journal of Business Venturing, 28(4), 564–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.05.001.

Feige, E. L. (1994). The transition to a market economy in Russia: Property rights, mass privatization and stabilization. In G. S. Alexander & G. Skapska (Eds.), A forth way? Privatization, property and the emergence of New Market economies (pp. 57–78). Abingdon: Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315021447-4.

Fuentelsaz, L., Gonzalez, C., Maicas, J. P., & Montero, J. (2015). How different formal institutions affect opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship. Business Research Quarterly, 18(4), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2015.02.001.