Abstract

Background: Unintended hepatic injury associated with the use of paracetamol (acetaminophen)-containing products has been growing.

Objective: The aim of the study was to seek a better understanding of the causes of this observation in order to evaluate the potential impact of proposed preventive measures.

Study Design: Retrospective analysis of a large database containing prospectively collected patient exposure data, clinical symptomatology and outcome.

Setting: The National Poison Data System database for 2000–7 involving exposures to paracetamol and an opioid was obtained and analysed. This dataset was limited to non-suicidal cases in patients 13 years of age and older. For comparison, the parallel, mutually exclusive dataset involving exposures to one or more non-opioid containing paracetamol products was analysed.

Outcome Measure: Trends in the numbers of patients exposed, treated, and mildly and severely injured were obtained and compared with each other and with trends calculated from publicly available data on sales and population. The association of injury with the number of paracetamol-containing products and the reason for taking them were also assessed.

Results: Comparators: During the study period, the US population of those 15 years of age and over rose 8.5%; all pharmaceutical-related calls to all US poison centres rose 25%. For the 8-year period from 2001 to 2008, sales of over-the-counter paracetamol products rose 5% (single-ingredient products fell 3%; paracetamol-containing combination cough and cold products rose 11%) and prescription paracetamol combination products rose 67%.

Opioids with paracetamol: A total of 119 731 cases were identified, increasing 70% over the period. The exposure merited acetylcysteine treatment in 8995 cases (252% increase). In total, 2729 patients (2.3%) experienced some hepatic injury (500% increase). Minor injuries rose faster than severe injuries (833% vs 280%) and most injuries (73.0%) were from overuse of a single combination product only, but the injury rate increased with use of more than one paracetamol-containing product. Abuse and misuse accounted for 34% of cases but 58% of the severe injuries.

Paracetamol without opioid: A total of 126 830 cases were identified, increasing 44%, and 15 706 cases merited acetylcysteine (70% increase). A total of 4674 patients (3.7%) experienced some hepatic injury (134% increase). Use of more than one non-opioid paracetamol product occurred in 7.3% of patients and was associated with a lower injury rate.

Conclusions: Hepatic injury associated with paracetamol use is increasing significantly faster than population, paracetamol product sales and poison centre use. This suggests a growing portion of consumers is self-dosing paracetamol beyond the toxic threshold. This is true for paracetamol with and without opioids, but the increase in hepatic injury is greater when paracetamol is taken with an opioid. This disproportionate rise is greatest with misuse and abuse of paracetamol products in combination with opioids. Increasing self-dosage of the opioid combination products for the opioid effect is likely to result in more cases of toxic exposure to paracetamol. In contrast, cases of exposure to paracetamol-containing cough and cold products are underrepresented among those injured. In the absence of opioid-containing products, consumption of more than one paracetamol-containing product did not contribute to injury. Efforts to modulate unintentional paracetamol-related hepatic injury should consider these associations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is one of the most commonly used analgesics in the US, with 25 billion doses sold in 2008.[1] The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and US FDA investigators estimate an annual average of 33 520 paracetamol overdose-related hospitalizations; this number has been rising.[2] Of the adults hospitalized for care, up to one-quarter may follow non-suicidal exposures.[2–5] Paracetamol has been implicated in about half of the cases of acute liver failure and is the leading cause of drug-induced liver injury.[6] In one study, 63% of 131 patients experiencing unintended acute liver failure took combination paracetamol/opioid medications, and 38% took more than one paracetamol-containing medication.

These findings have prompted calls for a change in labelling, dose and use of paracetamol,[7] and have prompted the FDA to convene a joint advisory committee to make recommendations to address the public health problem of liver injury related to the use of paracetamol in both non-prescription and prescription products.[8,9] Some of these recommendations are controversial and have been opposed.[10]

Paracetamol is used around the world, and the combination paracetamol with opioid product is available in many countries. Abuse of prescription opioid products is rising in Europe, Asia, South America and the Middle East.[11,12] The recent experience in the US of rising paracetamol related hospitalizations and acute liver failure, especially associated with abuse of opioid containing agents, may be repeated in other countries.[2,5] We therefore sought to evaluate the potential impact of these recommendations using a broader database of unintentional paracetamol exposure, including those with less severe injury.

Methods

The National Poison Data System (NPDS) of the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) is a large database of medication-exposed patients, including those who experience minor or no injury. Using this database, our goal was to assess the trend in paracetamol-related injury by type of product, number of products used and reason for use.

Data from the NPDS were accessed for this study. Over 2 million new cases are reported annually to this database.[13] Patients or their physicians call poison centres following a variety of medication exposures, most commonly after unintentional paediatric exposures, acute and chronic excess dosing, inadvertent medication error, adverse drug reactions, medication interactions, drug abuse and suicide. The most common inquiries are for dose-related risk assessment before symptoms, and for management advice with symptoms. Not all cases result in symptoms or injuries. Poison centres remain involved and cases are followed by phone until outcome is determined. Case data are recorded locally in real time in a standardized computer format and is uploaded to the NPDS electronically at the time of the initial contact and as the case progresses. Patient identifiers are not transmitted from the individual poison centre to the national database. Categories of information include patient and caller demographics, the exposure scenario, the substance(s), symptoms and signs of clinical toxicity, treatment and medical outcome. Each category of data has a limited set of entry options. Local free-text notes are not uploaded. Criteria for each type of entry are standardized nationally, and poison specialists are trained to ensure that these criteria are used for all data entries.

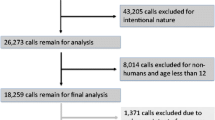

The AAPCC NPDS records for 2000–7 involving human exposures to one or more prescription opioids (hydrocodone, oxycodone, codeine, tramadol, methadone, morphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone), along with paracetamol, were obtained (paracetamol with opioid). This dataset was limited to subjects aged 13 years of age and older. Suicidal cases (i.e. intended injury) were excluded. Exposures were characterized by the number and type of paracetamol-containing products. Exposures were further characterized by reason for exposure.

The AAPCC NPDS records for 2000–7 involving exposures to one or more non-opioid paracetamol products were similarly obtained (paracetamol without opioid). Exposures were further characterized by reason for exposure.

The frequency of cases, frequency of cases in which acetylcysteine was recommended and/or administered, and incidence of medication-related minor hepatic injury (using the standard NPDS clinical effect code of AST or ALT >100 IU/L and ≤1000 IU/L) and medication-related severe hepatic injury (using the standard NPDS clinical effect code AST or ALT >1000 IU/L) were calculated and compared between groups. We chose this marker of paracetamol-induced hepatic injury instead of other indicators of acute liver failure because it is collected in a standard manner in this database and is a more sensitive marker of injury to prompt public health intervention to prevent acute liver failure.

For comparison, and for evaluation of potential reporting bias, we used publicly available data to describe and compare trends in the US population from 2000 to 2007, all pharmaceutical-related calls to US poison centres from 2000 to 2007, sales of over-the-counter paracetamol single ingredient products from 2001 to 2008, over-the-counter paracetamol combination cough and cold products from 2001 to 2008 and prescription paracetamol products from 2001 to 2008.[13–15] The publicly available data did not contain the year 2000.

NPDS data were imported into a structured query language (SQL) database and analysed using Microsoft® Excel 2010 (Microsoft® Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Summary data for analysis were imported to Statistical Analysis System (SAS) v9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). General linear models using least squares regression analysis were used to analyse trends and trend comparisons. Comparisons of proportions were done using Chi-square tests. All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS. Unless otherwise stated, statistical difference is based on p<0.05.

Approval for data use was obtained from the AAPCC Data Access Committee and its board of directors. Data were provided to the investigators in a coded fashion to maintain blinding to the individuals and poison centres. The study was also reviewed by the institutional review board at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and deemed exempt.

Results

Comparator

During the study period, the US population of those aged 15 years and over rose 8.5%. All pharmaceutical-related calls to all US poison centres rose 25%. For the 8-year period from 2001 to 2008, sales of non-prescription paracetamol products rose 5% (single-ingredient products fell 3%; paracetamol-containing combination cough and cold products rose 11%) and prescription paracetamol combination products rose 67%.

Paracetamol with Opioid

A total of 119 731 cases were identified (106 970 single-exposure cases and 12 761 multiple paracetamol product-exposure cases). Only 2% were exposed to an opioid and paracetamol not in a combination product. Cases increased 70% over the period 2000–7 (see figure 1). In total, 55078 cases were evaluated at a healthcare facility. Acetylcysteine treatment was recommended/ administered in 8995 (7.5%) cases, while 1614 patients experienced minor hepatic injury and 1115 experienced severe hepatic injury (41% of injuries). These included 165 deaths and 9 living patients who had undergone a transplant. Recommendations for acetylcysteine rose 252%, minor injuries rose 833%, severe injuries rose 280% (see figure 1) and both together rose 500% (all trends p<0.01). Only 7% of recommendations for acetylcysteine were documented not to have received this drug, accounting for only 3% of injuries (see table I).

The rates of injury associated with single and various multiple paracetamol with opioid combination exposures are shown in table II. The injury rate increased with the number of different products, but 87% of exposures and 73% of injuries were from exposure to a single combination product.

Abuse of paracetamol with opioid medication accounts for only 16% of exposures to these products, but accounts for 27% of all related injuries. Misuse of paracetamol with opioid medication accounts for 19% of exposures, but accounts for another 32% of injuries. Abuse, misuse and reason unknown accounted for 89% of deaths or transplantations. The hepatic injury rate associated with abuse and misuse was 3.8%, many times more than the rate of 0.8% observed with unintentional ingestion, therapeutic error and adverse effect (p<0.01), but less than the 5.4% rate associated with reasons unknown, which may include some suicide cases (p<0.01) [see table III]. Over the study period, the injury rate following misuse or abuse rose 172%, and the injury rate associated with unintentional ingestion, therapeutic error and adverse effect rose 121% (see figure 1).

Paracetamol without Opioid

In total, 126830 cases were identified: 75 788 from single-ingredient paracetamol products, 41 788 from over-the-counter paracetamol-containing combination cough and cold products and 9254 from multiple paracetamol-containing products. Reported cases increased 44% over the 7-year period (see figure 2 [same scale as figure 1]); 53 802 cases were evaluated at a healthcare facility. Acetylcysteine treatment was recommended/ administered in 15 706 cases (12.4%). In addition, 2091 patients experienced related minor hepatic injury and 2583 experienced related severe hepatic injury (55% of all injuries). These included 267 deaths and 23 living patients who had undergone a transplant. Recommendations for acetylcysteine rose 70%, minor injuries rose 161%, severe injuries rose 116% and both injuries together rose 134% (all trends p< 0.01) [see figure 2]. Only 4% of recommendations for acetylcysteine were documented not to have received acetylcysteine, accounting for only 2% of injuries (see table I). Although non-prescription paracetamol-containing combination cough and cold products accounted for 60% of non-prescription paracetamol product sales, they accounted for only 35% of all single-product cases, 7% of acetylcysteine treatment and 3% of hepatic injuries in this group.

The rates of injury associated with single and multiple exposures are shown in table II. The rate of injury following exposure to multiple paracetamol without opioid products was actually less than that from overuse of a single product (p< 0.01).

Abuse and misuse of these paracetamol-containing products accounted for 30% of exposures and 51% of all injuries, while abuse, misuse and reason unknown accounted for 83% of deaths or transplantations. Only 41% of cases were coded as therapeutic error or adverse effect and these only accounted for 13% of injuries. The rest were coded as reason unknown (8%) or ‘unintentional —general’ (21%) [see table III].

A lower portion of paracetamol with opioid patients received acetylcysteine (7.5% vs 12.4%), but the injury rate (all hepatic injuries) was not statistically different for those who received acetylcysteine (27.0% vs 27.8%). This suggests that similar paracetamol treatment criteria are being used in both groups. The different acetylcysteine recommendation rates are not surprising since opioid-related toxicity, not just paracetamol-related risk, may account for a significant part of poison centre advice requests in that group.

Trends for population, all pharmaceutical cases, sales, paracetamol cases with opioids, paracetamol cases without opioids, acetylcysteine-treated paracetamol cases with opioids, acetylcysteine-treated paracetamol cases without opioids, minor, major and all hepatic injuries after paracetamol with opioids, and minor, major and all hepatic injuries after paracetamol without opioids were compared, and the five paracetamol with opioid trends were compared with the five paracetamol without opioid trends. All trends were statistically different from the others, with the exception of three: population versus sales of paracetamol without opioid (8.5% vs 5.3%); sales of paracetamol with opioid versus cases of paracetamol with opioid exposure (67% vs 70%); and major versus all hepatic injuries after paracetamol without opioids (116% vs 134%).

Discussion

In both groups (paracetamol with and without opioid) overuse, treatment and hepatic injuries are rising faster than population, sales and all pharmaceutical calls to poison centres. All trends (use, treatment and injury) were greater for paracetamol with opioids. Paracetamol with opioid-related hepatic injuries rose much faster than paracetamol without opioid-related injuries —500% versus 134% over the same period. Injuries rose even though an increasing percentage of patients are being treated with acetylcysteine. Since paracetamol-induced hepatic injury is dose related, these comparative trend data suggest that, in the US, a greater percentage of consumers in both groups, but especially paracetamol with opioids, are taking larger hepatotoxic doses of paracetamol.

Consumers do not take these higher doses with the intention of causing hepatic injury. The rate of injury following paracetamol without opioid exposure was stable for unintentional dose exposure (e.g. therapeutic error) but was higher, and increased further, for intentional, higher dose exposure (e.g. therapeutic misuse for pain control). For paracetamol with opioids, more injuries and a rising portion of injuries are associated with therapeutic misuse (self-administration of higher dose) or abuse.

In spite of a dominant share of non-prescription paracetamol sales (60%), only 3% of injuries followed use of non-opioid multi-ingredient cough and cold products alone. Ninety-five percent of injuries followed single-ingredient paracetamol, and 2% involved single-ingredient paracetamol and a non-opioid multi-ingredient cough and cold product. Furthermore, when multiple paracetamol-containing products are associated with injury, it is almost exclusively in the context of at least one paracetamol with opioid product. The injury rate following multiple paracetamol without opioid product exposures was actually lower than following single-product paracetamol without opioid exposures, suggesting that inadvertent administration of a second paracetamol-containing substance is not a major cause of injury unless it is in the context of opioid use/abuse.

Although most patients intended to take the medication dose they actually took, it does not mean they understood and accepted the potential consequences of their action. As others have suggested, intentionally high dosing in a desire to treat pain (i.e. misuse) is likely the reason for most injuries in both medication groups.[6] In the case of paracetamol with opioid combination products, many patients may have dismissed the risk of the paracetamol component. In the context of either pain relief or abuse, many may have inadvertently increased their dose of paracetamol as they became habituated to the opioid component and increased their dose of the combination product.

This study thus supports the FDA panel’s recommendation to remove paracetamol from opioid products but not to remove paracetamol from non-prescription combination cough and cold products.[8] While it has always been true that removing paracetamol from opioid combination products would eliminate these products as a source of paracetamol-related injury, this study provides additional motivation, demonstrating that these products represent a significant and growing portion of those unintentionally injured from overuse of paracetamol. Manufacturers and regulators should reconsider the cost/benefit of eliminating combination opioid products. These medications can work synergistically in cancer pain but there is no effective dose combination that is stable both over time and between patients.[16] Opioid habituation occurs, requiring increased opioid dosing, but paracetamol requirements do not rise.

For paracetamol without opioid, patients intentionally taking more medication probably did not understand the dangers of excess paracetamol. Only 50% of patients achieve good to excellent headache pain relief at 650 mg, 65% at 975 mg and 75% at 1300 mg.[17] A significant portion of the public perceives paracetamol as a safe medication and will continue to increase their dose until pain is relieved.[8] Many injured patients in this study took more than the recommended dose of single-ingredient paracetamol. Although considered as a preventive measure, there is no evidence that lowering the recommended dose or tablet size will result in fewer injuries, particularly if the total dose is below 650 mg.[8]

In this study, 3755 adult patients were hospitalized, and 3088 were treated each year. The CDC estimates there are approximately 8000 adult, non-suicidal, paracetamol-related, hospitalizations per year.[2–5] The use of transaminase elevation as the hepatic injury marker adds sensitivity over using acute hepatic failure alone. These markers were more easily followed, more completely recorded and recorded in a standardized fashion in the database. Although our screen was sensitive but not specific, our study identified an average of 462 severe injuries, including 58 dead/living patients who had undergone a transplant per year. This closely matches estimates for the entire US from other sources. Estimates from a multi-year, multicentre study of acute liver failure suggest there may be at least 110 acute liver failure cases from non-suicidal paracetamol exposure in the US each year.[6] Another study extrapolated the number to 400 per year.[18] Thus, it is likely that our database includes a large portion of the affected individuals in the US, and is representative.

One limitation of this dataset is the passive nature of data collection. Not all cases may be reported and not all features of every case may be in the database. Some patients with hepatotoxicity may not be identified as such. Reasons for seeking help may lead to differential reporting rates between paracetamol with and without opioid exposures. However, the use of trend analysis over time rather than head-to-head comparison of raw injury rates between paracetamol with and without opioid groups corrects for this difference. There is no reason to believe that case reporting or injury identification increased disproportionately in the paracetamol with opioid group; thus, comparing the rate of increase in cases, treatments and hepatic injuries should be valid, particularly with the use of baselines inside and outside the database.

In 10% of the paracetamol without opioid deaths and 25% of paracetamol with opioid deaths, AST or ALT was recorded as <1000 IU/dL. As noted, recording may be incomplete. We would expect underrecording to be uniform; thus, it is possible that some (possibly 15–25%) of the paracetamol with opioid-related deaths were delayed deaths related to hypoxic brain injury with transient or non-fatal hypoxic or paracetamol-related injury. Given the large number of injuries and deaths in both groups, this should not affect the conclusions.

Conclusions

Injury related to paracetamol with opioid use has increased dramatically. Abuse and misuse accounted for most for the injuries. Exposure to multiple products increased the risk. In contrast, paracetamol without opioid product exposure and injury rose more slowly, but still significantly faster than secular trends. Following paracetamol without opioid exposure, injury was almost exclusively the result of single-product overuse, not simultaneous use of more than one paracetamol-containing product. These data support action to address this epidemic, including proposals to address abuse of these products, to remove paracetamol from products with opioids and educating the public on the risk of paracetamol overuse.

References

Woodcock J. A difficult balance: pain management, drug safety, and the FDA. N Engl J Med 2009; 261: 2105–7

Manthripragada A, Zhou E, Budnitz D, et al. Characterization of acetaminophen overdose-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011; 20: 819–26

Schiødt FV, Rochling FA, Casey DA, et al. Acetaminophen toxicity at an urban county hospital. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1112–7

Bond GR, Hite LK. Population based incidence and outcome of acetaminophen poisoning by type of ingestion. Acad Emerg Med 1999; 6: 1115–20

Myers RP, Shaheen AA, Li B, et al. Impact of liver disease, alcohol abuse, and unintentional ingestions on the outcomes of acetaminophen overdose. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6: 918–25

Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, et al. Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multi-center, prospective study. Hepatology 2005; 42: 1364–72

Lee WM. Acetaminophen toxicity: changing perceptions on a social/medical issue. Hepatology 2007; 46: 966–70

Joint Meeting of the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee with the Anesthetic and Life Support Drugs Advisory Committee and the Nonprescription Drugs Advisory Committee: meeting announcement [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/advisorycommittees/calendar/ucm143083.htm [Accessed 2010 Dec 11]

Krenzelok EP. The FDA Acetaminophen Advisory Committee Meeting: what is the future of acetaminophen in the United States? The perspective of a committee member. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2009; 47: 784–9

American Pain Foundation’s position statement regarding the FDA Advisory Committee’s recommendations concerning acetaminophen. Release date: September 14, 2009 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.painfoundation.org/about/position-statements/fda-acetaminophen-recommendations.html [Accessed 2011 Jul 6]

Kuehn BM. Prescription drug abuse rises globally. JAMA 2007; 29: 1306

United Nations. International Narcotics Control Board 2010 report [online]. Available from URL: http://www.incb.org/incb/en/annual-report-2010.html [Accessed 2011 Jul 2]

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. WISQARS nonfatal injury reports [online]. Available from URL: http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/nfirates2001.html [Accessed 2010 Oct 18]

National Poison Data System. Annual reports of the American Association of Poison Control Centers 2000–2007 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.aapcc.org/dnn/NPDSPoisonData/NPDSAnnualReports.aspx [Accessed 2010 May 24]

Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Joint Nonprescription Drugs Advisory Committee and Pediatric Advisory Committee Meeting. Over-the-counter acetaminophen-containing drug products in children: background package. May 17–18th, 2011 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/NonprescriptionDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM255306.pdf [Accessed on 2011 Jul 6]

Stockler M, Vardy J, Pillai A, et al. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) improves pain and well-being in people with advanced cancer already receiving a strong opioid regimen: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled cross-over trial. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 3389–94

Neirenburg DW, Melmon KL. Introduction to clinical pharmacology and rational therapeutics. In: Melmon KL, Carruthers SG, editors. Melmon and Morrelli’s clinical pharmacology: basic principles in therapeutics. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional, 2000: 3–62

Bower WA, Johns M, Margolis HS, et al. Population-based surveillance for acute liver failure. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 2459–63

Acknowledgements

The AAPCC (http://www.aapcc.org) maintains the national database of information logged by the country’s 61 Poison Control Centers (PCCs). Case records in this database are from self-reported calls; they reflect only information provided when the public or healthcare professionals report an actual or potential exposure to a substance (e.g. an ingestion, inhalation or topical exposure, etc.) or request information/ educational materials. Exposures do not necessarily represent a poisoning or overdose. The AAPCC is not able to completely verify the accuracy of every report made to member centres. Additional exposures may go unreported to PCCs, and data referenced from the AAPCC should not be construed to represent the complete incidence of national exposures to any substance(s). The authors’ opinions do not necessarily represent those of the AAPCC or its member centres.

Preliminary analyses of these data were presented at the meeting of the European Association of Poison Centres and Clinical Toxicologists, Bordeaux, France, 13 May 2010, and the Joint Conference of the American College of Medical Toxicology and the Israel Society of Toxicology, Haifa, Israel, 16 November 2010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/11630980-000000000-00000.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bond, G.R., Ho, M. & Woodward, R.W. Trends in Hepatic Injury Associated with Unintentional Overdose of Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) in Products with and without Opioid. Drug Saf 35, 149–157 (2012). https://doi.org/10.2165/11595890-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11595890-000000000-00000