Abstract

Objectives

To estimate and compare incidence/prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in different geographic health regions and between urban/rural locations of residence within the province of Saskatchewan.

Methods

Saskatchewan Provincial Administrative Health Databases (2001–2014) were utilized as data sources. Two RA case-definitions were employed: (1) three physician billing diagnoses, at least one of which was submitted by a specialist (rheumatologist, general internist, or orthopedic surgeon) within 2 years; (2) one hospitalization diagnosis (ICD-9-CM code-714 and ICD-10-CA codes-M05, M06). Data from these definitions were combined to estimate annual RA incidence and prevalence. Annual incidence and prevalence rates across geographic regions and between rural and urban residences were examined.

Results

An increasing RA prevalence gradient was observed in a south to north direction within the province. In the 2014–2015 Fiscal Year, the southern region of Sun Country had a 0.57% RA prevalence and the Northern Health Regions a prevalence of 1.15%. Incidence rates fluctuated over time in all regions but tended to be higher in Northern Health Regions. A higher RA prevalence trend was observed in rural residents over the study period.

Conclusions

Higher prevalence rates were observed for RA in Northern Health Regions than elsewhere in the province. Rural prevalence rates were higher than for urban residents. Healthcare delivery strategic planning will need to ensure appropriate access for RA patients throughout the province.

Résumé

Objectifs

Estimer et comparer l’incidence et la prévalence de la polyarthrite rhumatoïde (PR) entre différentes régions sanitaires et entre les lieux de résidence urbains et ruraux de la province de la Saskatchewan.

Méthode

Nos données sont extraites des bases de données administratives sur la santé de la Saskatchewan (2001–2014). Nous avons employé deux définitions de cas pour la PR: 1) > trois factures de diagnostic médical, dont au moins une soumise par une ou un spécialiste (rhumatologue, interniste général(e) ou chirurgien(ne) orthopédiste) en l’espace de deux ans; 2) > un diagnostic d’hospitalisation (code CIM-9-MC 714 et codes CIM-10-CA M05 et M06). Nous avons combiné les données de ces définitions pour estimer l’incidence et la prévalence annuelles de la PR. Nous avons ensuite examiné les taux d’incidence et de prévalence annuels d’une région géographique à l’autre et entre les lieux de résidence urbains et ruraux.

Résultats

Un gradient de prévalence de la PR croissant du sud vers le nord a été observé dans la province. Durant l’exercice 2014–2015, le taux de prévalence de la PR était de 0,57% dans la région sanitaire de Sun Country, dans le sud de la Saskatchewan, et de 1,15% dans les régions sanitaires du nord. Les taux d’incidence ont fluctué dans le temps dans toutes les régions, mais ont eu tendance à être plus élevés dans les régions sanitaires du nord. Une prévalence supérieure de la PR a été observée chez les résidents des milieux ruraux au cours de la période de l’étude.

Conclusions

Les taux de prévalence observés pour la PR dans les régions sanitaires du nord étaient plus élevés qu’ailleurs dans la province. Les taux de prévalence des résidents des milieux ruraux étaient supérieurs à ceux des résidents des milieux urbains. Dans la planification stratégique, il faudra donc veiller à ce que les patients atteints de PR aient accès aux soins de santé appropriés dans toute la province.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Geography has been recognized as a determinant of health in the 2002 Commission on Future of Health Care in Canada Report (Romanow 2002). In the care of people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), those who live in rural and remote locations may face greater challenges in accessing specialty care (Nair et al. 2016). As access to specialty care has been associated with improved outcomes and reduced healthcare overall costs for RA, limitations in access for segments of the provincial population may represent an important inequity (Ruderman et al. 2012; Singh et al. 2016). Timely diagnosis and treatment are becoming increasingly crucial with the recent advances in therapeutic interventions and amelioration of joint destruction in this disease (Singh et al. 2016). Understanding the incidence and prevalence of RA in geographically more remote areas may inform future healthcare service delivery planning.

Saskatchewan is a Canadian province with a land area of 588,239.21 km (Statistics Canada 2011a). Two thirds of the population reside in urban areas, and the majority of people live in the southern half of the province. Saskatoon and Regina are the two cities where the tertiary medical care centres for the province are located as well as where all the province’s subspecialist rheumatologists practice. Saskatchewan is divided into 12 regional health authorities and one health authority (Athabasca Health Authority) funded jointly by the provincial and federal governments. The rural population is distributed in smaller communities, some quite isolated and, depending on weather and season, may not be accessible by road. Delivery of healthcare services to rural and remote residents will pose a particular challenge to ensure equitable access, availability, and affordability compared to their urban counterparts.

The objectives of this study were to:

-

1.

Estimate and compare the incidence/prevalence of RA in different geographic regions in the province.

-

2.

Compare annual incidence/prevalence of RA between those who reside in a rural location and those in an urban location.

Methods

Setting and Design

Saskatchewan is one of Canada’s three prairie provinces and as of January 2015 had a population of 1,129,061 (Statistics Canada 2015). The majority of Saskatchewan residents are recipients of provincial healthcare benefits. Exceptions (< 1%) would include federally insured persons such as federal prison inmates, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and military personnel. These federally insured groups would have information captured in data collected around hospital use but not other data sources employed in this study. Additionally, First Nations peoples who have treaty relationships with the federal government, termed “Registered Indians” (RI), and who comprise 15.6% (2011 Statistics Canada: National Household Survey data) of the provincial population receive some of their health benefits from the Federal Government. Relevant data from these populations with Federal treaty relationships were incorporated within the data sources employed in this study (Statistics Canada 2011b).

A Saskatchewan provincial population-based cohort study was undertaken to evaluate incidence and prevalence rates of RA between fiscal year 2001 and 2002 (FY0102) overall, by gender, by location of residence (rural/urban), and by geographic health region.

Subjects and Data Sources

This retrospective, population-based cohort study was performed employing Saskatchewan Provincial Health Administrative Databases organized by fiscal year (FY), for the periods of April 1, 2001 up until March 31, 2015. Provincial Health Administrative Databases utilized for this study included the Discharge Abstract Database, the physician Medical Services Database, the Person Health Registration System, and the Vital Statistics Registry. These various data sources can be linked anonymously through unique personal health insurance numbers.

The Discharge Abstract Database incorporates detailed hospitalization-related data. Until March 31, 2001, prior to the study time period, diagnoses were recorded in compliance with the International Classification of Diseases 9th revision (ICD-9). Subsequently, the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Canadian Version (ICD-10-CA) was introduced. During the 12-month period from April 1, 2001 until March 31, 2002, approximately 90% of ICD codes recorded are ICD-10-CA with the remaining 10% being ICD-9. Subsequent to April 1, 2003, virtually all codes were recorded in the ICD-10-CA format. Between 3 and 16 diagnoses are captured in each record prior to the introduction of ICD-10-CA, and up to 25 diagnoses are captured subsequently. The database provides detailed diagnostic information, including the primary admission diagnosis as well as co-morbidity diagnoses and diagnoses related to complications arising during the hospitalization.

The Medical Services Database provides data on physician services. Physicians who are paid on a fee-for-service basis submit billing claims to the provincial health ministry. A single diagnosis using three-digit ICD-9 codes is recorded on each claim. Physicians who are salaried are generally required to submit billing claims for administrative purposes, a practice known as shadow billing.

The Person Health Registration System captures characteristics of each insured individual, including their age, sex, location of residence, and dates of coverage within the provincial health insurance plan.

The Vital Statistics Registry holds information on all births and deaths within the province.

Cohort Case Definition

Rheumatoid Arthritis

A previously validated algorithm for administrative data was employed in the identification of people with RA for this cohort (Widdifield et al. 2013). Individuals were identified as having RA if they had three or more physician services claims for RA (ICD-9 code 714), at least one of which was submitted by a specialist (rheumatologist, general internist, or orthopedic surgeon) within a 2-year period or if they had one or more hospitalizations with a diagnosis of RA (ICD-9 code 714, ICD-10 codes: M05, M06) in any of the up to 25 diagnosis fields. When an individual met both the physician visit and hospitalization criteria, the earliest occurrence was taken as the index date of diagnosis. For inclusion in this cohort, individuals were required to be age 18 or older on the index date of their RA diagnosis and have uninterrupted health insurance coverage (i.e., a gap of no more than three consecutive days in coverage) from the date of their diagnosis until March 31, 2015 or their exit from the cohort.

To distinguish incident from prevalent RA, a lead time of 2 years was used based on the clinical judgement that a person is unlikely to go more than 2 years without seeking medical attention for their newly developing RA. Individuals having 2 or more years of insurance coverage prior to their diagnosis of RA were identified as having incident RA. Anyone with less than 2 years of health insurance prior to their diagnosis with RA was included in the cohort to ensure prevalence estimates in subsequent years were accurate. They were included in incidence estimates, although they were flagged to determine the potential overestimation of the incidence of RA.

Death

The date of death was identified from the Vital Statistics Registry. An individual who died between April 1 and March 31 of the following year was described as having died in that fiscal year.

Covariates

Descriptive variables were identified for each member of the cohort. All variables were determined on the day of RA diagnosis. These included age (categories 18– < 45, 45– < 55, 55– < 65, 65– < 75, 75+ years), sex (male, female), insurance coverage (< 2 years, 2+ years), location of residence (urban, rural, missing), and regional health authority (RHA) of residence. Age, sex, and insurance coverage were obtained from the Person Health Registration System. Designation of location of residence as urban or rural was determined using Statistics Canada categorizations (Statistics Canada 2016). An individual was identified as living in an urban area if their postal code was for a Census Metropolitan Area or Census Agglomeration Area with a population of 10,000 or more. Due to low population numbers in the three most northern health regions (Athabasca Health Authority, Keewatin Yatthé and Mamawetan Churchill River Regional Health Authorities), the data for these regions were collapsed into a single category labeled “Northern Saskatchewan.”

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics of the cohort were described for each fiscal year of the cohort. The bivariate associations of these characteristics when a person was first diagnosed with RA were tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for one categorical and one continuous variable and the chi-square test for two categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

The incidence rate of RA per 100,000 population at risk (PAR) was calculated for each fiscal year. As an example, in FY0102, the numerator is the number of people alive on April 1, 2001 who were diagnosed with RA between April 1, 2001 and March 31, 2002, inclusive. The denominator (i.e., the population at risk to develop RA) includes all individuals aged 18 years or older on April 1, 2001 with at least 1 day of health insurance coverage within the fiscal year after removing individuals with prevalent RA. The FY0102 population data was used as the reference for directing standardization of subsequent years.

The prevalence rate of RA per 100,000 PAR was calculated for each fiscal year. As an example, in FY0102, the numerator is the number of people alive on April 1, 2001 who were diagnosed with RA prior to April 1, 2001. Prevalence for this time-point was traced back to April 1, 1996. The denominator includes all individuals aged 18 years or older on April 1, 2001 with at least 1 day of health insurance coverage within the fiscal year in order to ensure maximal sensitivity in identification of the general population denominator. Prevalent cases were carried forward each year unless they died or had a gap in their health coverage longer than 3 days. This criterion was selected as people in SK retain uninterrupted coverage with gaps of a day or two in their provincial health insurance. However, employing a greater than 3-day exclusion criterion minimized risk of inaccuracies in cohort integrity through re-issuing of inactive health card numbers for new provincial residents.

Crude and adjusted incidence, prevalence rates, and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated for FY0102 to FY1415. Rates were stratified by sex (male, female), location of residence (urban, rural), and health region. Rates were adjusted to the age and sex distribution of the Saskatchewan population standard from fiscal year 2001/2002. Sex-stratified rates were also adjusted for age. The FY0102 population data was used as the reference for directing standardization of subsequent years.

All analyses were performed at the Saskatchewan Health Quality Council using SAS© statistical software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc. SAS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2007).

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University of Saskatchewan Biomedical Research Ethics Board.

Results

The cohort comprised 5757 people diagnosed with RA between April 1, 2001 and March 31, 2015. There were 3731 people diagnosed with RA between April 1, 1996 and March 31, 2001 and these were identified as having prevalent RA in FY0102.

Demographic characteristics were relatively stable over the 15-year period. In each fiscal year, women comprised roughly two thirds of incident cases, as did people living in an urban centre. The two largest RHAs—Saskatoon and Regina Qu’Appelle—together accounted for approximately half of incident RA cases. The proportion of incident RA cases with less than 2 years of health insurance prior to their diagnosis in each fiscal year ranged from 3.3 to 8.2%, with a mean of 5.9%.

Bivariate analyses (data not shown) revealed that women were, on average, younger than men when diagnosed with RA (58.6 vs 60.7 years) (p < 0.0001), as were individuals with < 2 years of prior insurance compared to those with 2+ years (48.8 vs 59.8 years) (p < 0.0001). Women were also more likely than men to live in an urban area (61.8 vs 57.5%) (p = 0.0004) and have < 2 years of insurance coverage prior to their diagnosis (74.2 vs 69.9%) (p < 0.0001). No other bivariate associations were statistically significant.

Incidence rates for RA fluctuated from year to year for the province and individual health regions but appeared generally to be higher in the Northern Saskatchewan health regions (Fig. 1). The female-to-male incidence ratio was approximately 2:1 in both urban and rural residential areas.

There is a trend towards increased RA prevalence over the time period studied for the province as a whole and in each health region (Fig. 2). For FY0102, the adjusted prevalence rate for Saskatchewan was 482.0 per 100,000 PAR (95%CI 466.7–497.7); this steadily increased each year to an adjusted prevalence rate of 683.4 (95% CI 666.6–700.6) in FY1415 (Table 1). There was variation in prevalence between health regions, with the Northern Saskatchewan health regions (Athabasca, Keewatin Yatthe, and Mamawetan Churchill River) having the highest rates and the three Southern Health Regions (Sun Country, Five Hills, and Regina Qu’Appelle) having the lowest prevalence rates (Fig. 3).

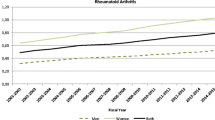

When examining the trends over time, it appears there is a small but consistently higher prevalence of RA in rural residents compared to urban over the time period examined. This is apparent for both genders but is greater for women, with no overlap in prevalence rate confidence intervals between rural and urban women from FY0506 onwards (Fig. 4). Higher prevalence rates were observed in the older age categories.

Discussion

Overall, for the province as a whole, our incidence and prevalence rates for RA are consistent with ranges reported from other jurisdictions both within Canada and the USA (Bernatsky et al. 2014; Widdifield et al. 2014; Myasoedova et al. 2010). However, in this geographic study of RA in Saskatchewan, we have found a general increase in prevalence rates moving north through the province. A similar trend for higher prevalence rates in the north has also been reported by Vieira for American RA patients (Vieira et al. 2010). An increased prevalence trend in rural over urban Saskatchewan populations was observed, which is consistent with the overall geographic regional findings within the province. This is in contrast to the recent findings of lower prevalence in rural compared to urban Quebec populations (Bernatsky et al. 2014). There are a number of potential geographically linked influences of particular relevance that may contribute to this observed prevalence gradient in the Saskatchewan environmental context.

Saskatchewan has substantial agricultural and mining activities. Regional variation in agricultural practices with crop/livestock farming and possibly varying intensities of pesticide/herbicide utilization have been postulated to have some association with RA prevalence (Taylor-Gjevre et al. 2015; Khuder et al. 2002; Parks et al. 2016). Mining activities in the province, including hard rock mining, may also contribute to a provocative environment for development of autoimmune disease (Klockars et al. 1987; Yahya et al. 2014). In other settings, air pollution and traffic pollution have been linked to increased risk of RA development (Hart et al. 2009). Prevalence of cigarette smoking exposure in the Northern regions of the province may possibly contribute to increased risk. There is some information to suggest cigarette smoking is more widespread in Northern Canada than in more southerly regions (Deering et al. 2009). Cigarette smoking exposure has been well recognized to play a causal role in development of RA (Di Giuseppe et al. 2014). There has been some evidence that tuberculosis exposure, which has been higher in the North, has also been linked to RA incidence (Shen et al. 2015; Long et al. 2013).

Genetic predisposition towards RA expression and ethnic variation between health regions may also contribute to variation in prevalence between areas. Some of this variation may relate to familial clustering related to settler patterns or to Indigenous communities within the province. There have been higher incidence/prevalence RA rates identified in some Indigenous populations in Canada (Barnabe et al. 2008). Greater proportions of Indigenous residents in Northern regions may contribute to some of the higher prevalence trends we observed.

Lower socio-economic conditions, including during childhood, have also been associated with higher risk for development of RA in adulthood (Parks et al. 2013). It is likely that one or more of these exposures or circumstances associated with risk of RA may be contributing to the variation in geographic prevalence that is described in this study. Evaluation of the relative contributions of these environmental and exposure factors towards the prevalence of RA in different geographic regions was beyond the scope of this current study.

Although the results from this study are in general agreement with incidence and prevalence data from other locations in North America derived from administrative data sources, it should be acknowledged that this study relies on the case definition for RA without capacity for clinical or serologic verification. This may result in under- or overestimation of disease. Our case definition included not only rheumatologist diagnosis of RA but also orthopedist and internal medicine specialist. This definition varied from the required rheumatologist diagnosis definition employed in some other studies (Bernatsky et al. 2014; Widdifield et al. 2014; Myasoedova et al. 2010; Lix et al. 2006). This variation was primarily selected due to a unique administrative coding environment during the study period in Saskatchewan, where many rheumatologists would not be distinguished within the database from internal medicine specialists. Additionally, given the relatively small populations in some health regions, the rate determinations as suggested by the wider 95% CIs seen for some regional rates may be potentially less reliable.

We observed gender differences in incidence/prevalence rate, as expected based on other epidemiologic studies (Bernatsky et al. 2014; Widdifield et al. 2014; Myasoedova et al. 2010). The increased incidence and prevalence rates in the older age categories are also consistent with findings from other investigators (Widdifield et al. 2014; Doran et al. 2002).

The data gathered on prevalence within provincial geographic jurisdictions will assist with planning future healthcare service delivery and access for people with RA living in more remote or rural locations in Saskatchewan. Further exploration of exposures or conditions contributing to variation in incidence/prevalence of RA may provide insight into modifiable influences impacting development of autoimmune disease in these regions.

References

Romanow RJ (2002). Building on values: the future of health care in Canada. Final report. The Romanow Commission Report. Ottawa (ON): Health Canada 2002. ISBN 0–662–33043-92. (Accessed 12 June 2016).

Nair, B. V., Schuler, R., Stewart, S., & Taylor-Gjevre, R. M. (2016). Self-reported barriers to healthcare access for rheumatoid arthritis patients in rural and northern Saskatchewan: a mixed methods study. Musculoskeletal Care, 14(4), 243–251.

Ruderman, E. M., Nola, K. M., Ferrell, S., Sapir, T., & Cameron, D. R. (2012). Incorporating the treat-to-target concept in rheumatoid arthritis. J Manag Care Pharm, 18(9), 1–18.

Singh, J. A., Saag, K. G., Bridges Jr., S. L., Akl, E. A., Bannuru, R. R., Sullivan, M. C., et al. (2016). 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatology, 68, 1–26.

Statistics Canada (2011a). Focus on geography series, 2011 census-province of Saskatchewan. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-pr-eng.cfm?Lang=Eng&TAB=1&GK=PR&GC=47 (Accessed 10 Jan 2017).

Statistics Canada: Saskatchewan annual population report calendar year 2015 (http://www.stats.gov.sk.ca/pop/stats/population/APR2015.pdf) (Accessed 10 Jan 2017).

Statistics Canada: Saskatchewan aboriginal peoples 2011b national household survey: http://www.stats.gov.sk.ca/stats/pop/2011Aboriginal%20People.pdf (Accessed 10 Jan 2017).

Widdifield, J., Bernatsky, S., Paterson, J. M., Tu, K., Ng, R., Thorne, J. C., et al. (2013). Accuracy of Canadian health administrative databases in identifying patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a validation study using the medical records of rheumatologists. Arthritis Care and Res, 65(10), 1582–1591.

Statistics Canada: Census metropolitan area (CMA) and Census agglomeration (CA) http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/92-195-x/2011001/geo/cma-rmr/cma-rmr-eng.htm (Accessed 12 June 2016).

Bernatsky, S., Dekis, A., Hudson, M., Pineau, C. A., Boire, G., Fortin, P. R., et al. (2014). Rheumatoid arthritis prevalence in Quebec. BMC Res Notes, 19(7), 937.

Widdifield, J., Paterson, J. M., Bernatsky, S., Tu, K., Tomlinson, G., Kuriya, B., Thorne, J. C., & Bombardier, C. (2014). The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Ontario, Canada. Arthritis Rheumatol, 66(4), 786–793.

Myasoedova, E., Crowson, C. S., Kremers, H. M., Therneau, T. M., & Gabriel, S. E. (2010). Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955-2007. Arthritis Rheum, 62(6), 1576–1582.

Vieira, V. M., Hart, J. E., Webster, T. F., Weinberg, J., Puett, R., Laden, F., Costenbader, K. H., & Karlson, E. W. (2010). Association between residences in U.S. northern latitudes and rheumatoid arthritis: a spatial analysis of the nurses’ health study. Environ Health Perspect, 118(7), 957–961.

Taylor-Gjevre, R. M., Trask, C., King, N., & Koehncke, N. (2015). Prevalence and occupational impact of arthritis in Saskatchewan farmers. J Agromedicine, 20(2), 205–216.

Khuder, S. A., Peshimam, A. Z., & Agraharam, S. (2002). Environmental risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis. Rev Environ Health, 17(4), 307–315.

Parks, C. G., Hoppin, J. A., De Roos, A. J., Costenbader, K. H., Alavanja, M. C., & Sandler, D. P. (2016). Rheumatoid arthritis in agricultural health study spouses: Associations with pesticides and other farm exposures. Environ Health Perspect, 124(11), 1728–1734.

Klockars, M., Koskela, R. A., Jarvinen, E., Kolari, P. J., & Rossi, A. (1987). Silica exposure and rheumatoid arthritis: a follow up study of granite workers 1940-81. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed), 294(6578), 997–1000.

Yahya, A., Bengtsson, C., Larsson, P., Too, C. L., Mustafa, A. N., Abdullah, N. A., Muhamad, N. A., Klareskog, L., Murad, S., & Alfredsson, L. (2014). Silica exposure is associated with an increased risk of developing ACPA-positive rheumatoid arthritis in an Asian population: evidence from the Malaysian MyEIRA case-control study. Mod Rheumatol, 24(2), 271–274.

Hart, J. E., Laden, F., Puett, R. C., Costenbader, K. H., & Karlson, E. W. (2009). Exposure to traffic pollution and increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Environ Health Perspect, 117(7), 1065–1069.

Deering, K. N., Lix, L. M., Bruce, S., & Young, T. K. (2009). Chronic diseases and risk factors in Canada’s northern populations: longitudinal and geographic comparisons. Can J Public Health, 100(1), 14–17.

Di Giuseppe, D., Discacciati, A., Orsini, N., & Wolk, A. (2014). Cigarette smoking and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a dose-response meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther, 16(2), R61.

Shen, T. C., Lin, C. L., Wei, C. C., Chen, C. H., Tu, C. Y., Hsia, T. C., et al. (2015). Previous history of tuberculosis is associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 19(11), 1401–1405.

Long, R., Hoeppner, V., Orr, P., Ainslie, M., King, M., Abonyi, S., et al. (2013). Marked disparity in the epidemiology of tuberculosis among aboriginal peoples on the Canadian prairies: the challenges and opportunities. Can Respir J, 20(4), 223–230.

Barnabe, C., Elias, B., Bartlett, J., Roos, L., & Peschken, C. (2008). Arthritis in aboriginal Manitobans: evidence for a high burden of disease. J Rheumatol, 35(6), 1145–1150.

Parks, C. G., D’Aloisio, A. A., DeRoo, L. A., Huiber, K., Rider, L. G., Miller, F. W., et al. (2013). Childhood socioeconomic factors and perinatal characteristics influence development of rheumatoid arthritis in adulthood. Ann Rheum Dis, 72(3), 350–356.

Lix L, Yogendran M, Burchill C, Metge C, McKeen N, Moore D, Bond R. Defining and validating chronic diseases: an administrative data approach. Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. July 2006. http://mchpappserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/reference/chronic.disease.pdf (Accessed 10 Jan 2017).

Doran, M. F., Pond, G. R., Crowson, C. S., O’Fallon, W. M., & Gabriel, S. E. (2002). Trends in incidence and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota, over a forty-year period. Arthritis Rheum, 46(3), 625–631.

Funding

This work was supported by the Noreen Sutherland—Rheumatoid Arthritis—Royal University Hospital Foundation Endowment Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University of Saskatchewan Biomedical Research Ethics Board.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

This study is based in part on de-identified data provided by the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not necessarily represent those of the Government of Saskatchewan or the Ministry of Health.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor-Gjevre, R., Nair, B., Jin, S. et al. Geographic variation in incidence and prevalence rates for rheumatoid arthritis in Saskatchewan, Canada 2001–2014. Can J Public Health 109, 427–435 (2018). https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-018-0045-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-018-0045-6