Abstract

In order to understand the dynamics of a second order delay differential equation with a piecewise constant argument, we investigate invariant curves of the derived planar mapping from the equation. All invariant curves are given in this paper.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The study of differential equations with piecewise constant argument (EPCA) initiated in [1, 2]. These equations represent a hybrid of continuous and discrete dynamical systems and combine the properties of both differential and difference equations, hence, they are of importance in control theory and in certain biomedical models [3]. In this paper the second order delay differential equation with a piecewise constant argument

where \(x''(t)\) denotes the second order derivative of \(x(t)\), \([t]\) denotes the greatest integer less than or equal to t, and \(g:\mathbb {R}\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is a continuous or at least piecewise continuous function, is considered. In 1987, Aftabizadeh et al. discussed the oscillatory and periodic properties of the solutions of (1) in [4]. In 1989, Gyori and Ladas investigated linearized oscillations of the solutions of (1) in [5]. Later, Wiener and Cooke considered oscillations of the solutions of systems of two differential equations with piecewise constant arguments in [6].

The invariant curve [7–11] is another interesting problem in the study of dynamics because it can be used to reduce a system to a 1-dimensional one. The problem of invariant curves is actually a part of the research on invariant manifolds. In 1997, Ng and Zhang studied the nonlinear \(C^{1}\) invariant curve of planar mapping \(G:\mathbb {R}^{2}\rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{2}\),

derived from (1) in [12] when g is nonlinear and gave the conditions that G has linear invariant curves when g is linear. In 2003, Yang et al. investigated nonlinear \(C^{0}\) invariant curves of (2) when g is nonlinear in [13]. So far, nonlinear invariant curves of (2) when g is linear have not been studied. So it is very interesting to look for nonlinear invariant curves of (2) when g is linear. In this paper all the invariant curves of the planar mapping G are given including the linear and nonlinear ones when g is linear.

2 Main results

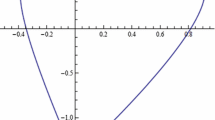

We discuss invariant curves of the form \(y=f(x)\) for the planar mapping (2). Its invariant curves of the form \(y=f(x)\) satisfy \(f(y)=2y-x-\frac {1}{2}(g(y)+g(x))\), which leads to the iterative functional equation

Considering linear g and \(g(x)=ax+b\), we compute that

Thus, the invariant curves of planar mapping G with \(g(x)=ax+b\) can be obtained by solving functional (4). We mainly discuss the generic cases \(a \notin\{-2, 4\}\), but leave the special cases \(a=-2\) and \(a=4\) to the last part of this section. For generic \(a\notin\{-2, 4\}\), (4) with \(b=0\) is of the form discussed in [14, 15]. In order to apply the results of [14], we let

which are the roots of the characteristic polynomial \(P(r):=r^{2} -(2-\frac{a}{2})r +1+\frac{a}{2}\).

From (5) we see that the characteristic roots \(r_{1}\), \(r_{2}\) of (4) have the following possibilities:

-

(C1)

\(0< r_{1}<1<r_{2}\), if and only if \(-2< a<0\).

-

(C2)

\(r_{1}=r_{2}=1\), if and only if \(a=0\).

-

(C3)

\(r_{1}<0<r_{2}\neq1\) and \(r_{1}\ne-r_{2}\), if and only if \(a<-2\).

-

(C4)

\(r_{1}=r_{2}<0 \), if and only if \(a=16\).

-

(C5)

\(r_{1}< r_{2}<-1\), if and only if \(a>16\).

Note that the case \(r_{2}>r_{1}>1\) is not listed because the case \(r_{2}>r_{1}>1\) implies \(\frac{(4-a)-(a^{2}-16a)^{\frac{1}{2}}}{4}>1\), i.e., \(-a>(a^{2}-16a)^{\frac{1}{2}}\), which does not hold, and that the case \(0< r_{1}<r_{2}<1\) is not listed because \(0< r_{1}<r_{2}<1\) implies \(0<\frac{(4-a)+(a^{2}-16a)^{\frac{1}{2}}}{4}<1\), i.e., \(0< a<4\), which contradicts the requirement that \(\Delta=a^{2}-16a\geq0\), and that the case \(0< a<16\) is not listed because in this case (4) with \(b=0\) has no continuous solutions, neither \(r_{1}\) nor \(r_{2}\) is real, by [14]. Since we consider \(a\notin\{-2, 4\}\), none of the case \(r_{1}=0\), the case \(r_{2}=0\), and the case \(r_{1}=-r_{2}\ne0\) is listed. Corresponding to the above list, we have the following results.

Theorem 2.1

(i) If \(-2< a<0\), then a continuous solutions ϕ of (4) with \(b=0\) is either of the piecewise linear form that \(f(x):= r_{i}x\) for \(x>0\), or \(:=0\) for \(x=0\), or \(:=r_{j}x\) for \(x<0\), where \(i,j=1, 2\), or given by

where \(x_{n}=\frac{r_{2}^{n}}{r_{2}-r_{1}}(x_{1}-r_{1}x_{0})+ \frac{r_{1}^{n}}{r_{2}-r_{1}}(-x_{1}+r_{2}x_{0})\), \(n \in\mathbb{Z}\), with an arbitrarily chosen \(x_{0}\in(-\infty, +\infty)\) and \(x_{1} \in[r_{1}x_{0}, r_{2}x_{0}]\), and \(f_{n}(x)=(r_{1}+r_{2})x-r_{1}r_{2}f_{n-1}^{-1}(x)\) for all \(x\in[x_{n}, x_{n +1})\), \(n=1, 2, \ldots \) , \(f_{-n-1}(x)=(\frac{1}{r_{1}}+\frac{1}{r_{2}})x-\frac {1}{r_{1}r_{2}}f^{-1}_{-n}(x)\) for all \(x\in[x_{-n}, x_{-n+1})\), \(n=1, 2, \ldots\) , and \(f_{-1}(x)=(\frac{1}{r_{1}}+\frac{1}{r_{2}})x-\frac {1}{r_{1}r_{2}}f_{0}(x)\), \(x\in[x_{0}, x_{1})\), with the arbitrarily chosen functions \(f_{0}\) such that \(f_{0}(x_{0})=x_{1}\), \(f_{0}(x_{1})=x_{2}\), and \(r_{1}\leq\frac{f_{0}(x)-f_{0}(y)}{x-y}\leq r_{2}\) for all \(x, y \in [x_{0}, x_{1})\). (ii) If \(a=0\), then (4) with \(b=0\) has a unique continuous solution f and \(f(x)=x+\beta\), where \(\beta\in\mathbb{R}\) is an arbitrary constant.

Proof

The proof is a simple application of well-known results in [14]. The result (i) is given by Theorem 2 of [14], where the characteristic roots \(r_{1}\), \(r_{2}\) satisfy \(r_{2}>1>r_{1}>0\) as shown in (C1). We can deduce the result (ii) from Theorem 8 of [14], where \(r_{1}=r_{2}=1\) as shown in (C2). The proof is completed. □

Theorem 2.2

(i) If \(a<-2\), then (4) with \(b=0\) only has two continuous solutions f and \(f(x)=r_{1}x\) or \(r_{2}x\). (ii) If \(a=16\), (4) with \(b=0\) just has a continuous solution \(f(x)=-3x\). (iii) If \(a>16\), all continuous solutions f of (4) with \(b=0\) are given by

where the sequence \(\{x_{n}\}\) is defined by \(x_{n}=\frac {r_{2}^{n}}{r_{2}-r_{1}}(x_{1}-r_{1}x_{0})+ \frac{r_{1}^{n}}{r_{2}-r_{1}}(-x_{1}+r_{2}x_{0})\), \(n\in\mathbb{Z}\), with an arbitrarily chosen \(x_{0}\in(0, +\infty)\) and \(x_{1} \in[r_{1}x_{0}, r_{2}x_{0}]\), and \(f_{2n-1}(x)=(r_{1}+r_{2})x-r_{1}r_{2}f_{2n-2}^{-1}(x)\), \(x\in [x_{-2n+5},x_{-2n+3})\), \(n=1, 2, \ldots \) , \(f_{2n}(x)=(r_{1}+r_{2})x-r_{1}r_{2}f_{2n-1}^{-1}(x)\), \(x\in [x_{-2n},x_{-2n+2})\), \(n=1, 2, \ldots \) , \(f_{-2n}(x)=(\frac{1}{r_{1}}+\frac{1}{r_{2}})x-\frac{1}{r_{1}r_{2}} f^{-1}_{-2n+1}(x)\), \(x \in[x_{2n+3}, x_{2n+1})\), \(n=1, 2,\ldots\) , \(f_{-2n-1}(x)=(\frac{1}{r_{1}}+\frac{1}{r_{2}})x-\frac {1}{r_{1}r_{2}} f^{-1}_{-2n}(x)\), \(x \in[x_{2n}, x_{2n+2})\), \(n=1, 2,\ldots\) , and \(f_{-1}(x)=(\frac{1}{r_{1}}+\frac{1}{r_{2}})x-\frac{1}{r_{1}r_{2}} f_{0}(x)\), \(x\in[x_{0}, x_{2})\), with an arbitrarily chosen continuous function \(f_{0}\) on \([x_{0},x_{2})\) such that \(f_{0}(x_{0})=x_{1}\), \(f_{0}(x_{2})=x_{3}\), and \(r_{1}\leq\frac {f_{0}(x)-f_{0}(y)}{x-y}\leq r_{2}\), \(\forall x, y \in[x_{0}, x_{2})\).

Proof

Firstly, we consider (i). By Theorem 5 in [14], (4) with \(b=0\) only has two continuous solutions f and \(f(x)=r_{1}x\) or \(r_{2}x\), where the characteristic roots \(r_{1}\), \(r_{2}\) satisfy \(r_{1}<0<r_{2}\neq1\) and \(r_{1}\ne-r_{2}\) as shown in (C3). Next, we consider (ii). By Theorem 6 in [14], (4) with \(b=0\) just has a continuous solution \(f(x)=-3x\), where the characteristic roots \(r_{1}\), \(r_{2}\) satisfy \(r_{1}=r_{2}=-3\) as shown in (C4). Finally, we consider (iii). In order to piecewise construct all solutions of (4) with \(b=0\) we need a partition for the interval \((-\infty, \infty)\). For this purpose we consider a homogeneous linear difference equation

which has the same coefficients as (4) with \(b=0\) correspondingly. Its characteristic equation is

which has two characteristic roots \(r_{1}\) and \(r_{2}\) satisfying \(r_{1}< r_{2}<-1\) as shown in (C5). Thus, (4) and (6) can be, respectively, rewritten as

If f is a solution of (4) with \(b=0\), we easily see that f is invertible. In fact, if \(f(x_{1})=f(x_{2})\), then \(f(f(x_{1}))=f(f(x_{2}))\). Thus, \(x_{1} = x_{2}\) by (4) because \(a\neq-2\), which implies that f is one to one. Next we only need to show that \(f(x)\rightarrow-\infty\) as \(x\rightarrow+\infty\) and \(f(x)\rightarrow+\infty\) as \(x \rightarrow-\infty\) because \(f(x)\rightarrow\pm\infty\) as \(x \rightarrow\pm\infty\), then the left-hand side of (4) with \(b=0\) tends to ±∞ by \(a>16\), but the right-hand side is equal to 0. Otherwise, \(f(x)\) has a finite limit as \(x \rightarrow\infty\), then \(f(f(x))-(2-\frac{a}{2})f(x)\) converges to a finite limit by the continuity of f on the whole of ℝ, but \((1+\frac{a}{2})x\) does not, which contradicts the requirement that \(f(f(x))-(2-\frac{a}{2})f(x)=-(1+\frac{a}{2})x\). Thus, we rewrite (4) in the following equivalent form:

which is called the dual equation to (4) with \(b=0\). Solving the homogeneous linear difference (9) with arbitrarily chosen real initial values \(x_{0}\) and \(x_{1}\), we obtain

Let \(x_{0}=x\) and \(x_{n+1}=f(x_{n})\) in (11), we have

Furthermore, we can obtain

where \(\Delta f^{n}(x, y)= \frac{f^{n}(x)-f^{n}(y)}{x - y}\) for any \(x\neq y\) and \(n\in\mathbb{Z}\). From (12) we can see that

Since f is strictly monotonic, \(\Delta f^{n}(x, y)>0\) for even n, which implies \(\Delta f(x, y)-r_{1}\geq0\) and \(-\Delta f(x, y)+r_{2}\geq0\), that is,

Moreover, we can see that \(f(0)=0\) from (13). In what follows, we arbitrarily choose \(x_{0}\in(0, +\infty)\) and \(x_{1}\in[r_{1}x_{0}, r_{2}x_{0}]\) and define a sequence \(\{x_{n}\}\), \(n\in\mathbb{Z}\), by (11). The sequences \(\{x_{2n}\}\), \(\{x_{2n+1}\}\), \(\{x_{-2n}\}\) and \(\{x_{-2n+1}\}\), where \(n=0, 1, 2,\ldots\) , are strictly monotone such that \(x_{2n}\rightarrow+\infty\), \(x_{2n+1}\rightarrow-\infty\), \(x_{-2n} \rightarrow0\), and \(x_{-2n+1} \rightarrow0\) as \(n \rightarrow\infty\). Thus, the sequence \(\{x_{n}\}\), \(n\in\mathbb{Z}\), is a partition of the interval \((-\infty, \infty)\). Next we arbitrarily choose a continuous function defined in the interval \([x_{0}, x_{2})\), satisfying \(f_{0}(x_{0})=x_{1}\), \(f_{0}(x_{2})=x_{3}\), and condition (14). We can recursively define the homeomorphisms \(f_{2n-1}: [x_{-2n+5}, x_{-2n+3})\rightarrow [x_{-2n}, x_{-2n+2})\), \(n=1, 2,\ldots\) , and \(f_{2n}: [x_{-2n}, x_{-2n+2})\rightarrow [x_{-2n+3}, x_{-2n+1})\), \(n=1, 2,\ldots\) , such that

In fact, for \(f_{2n}\) defined satisfying (16) and (18), we let

Obviously, \(f_{2n+1}(x_{-2n+3})=x_{-2n}\) and \(f_{2n+1}(x_{-2n+1})=x_{-2n-2}\). Making use of (18), we have \(\frac{1}{r_{2}} \leq\frac{f^{-1}_{2n}(x) - f^{-1}_{2n}(y)}{x-y} \leq\frac{1}{r_{1}}\) for \(x, y \in[x_{-2n}, x_{-2n+2})\). It is easy to deduce that

Furthermore, we again let

By the same argument we can see that

By induction both \(f_{2n-1}\) and \(f_{2n}\) are well defined. Similarly, we can also recursively define the homeomorphisms \(f_{-2n+1}: [x_{2n-2}, x_{2n}) \rightarrow [x_{2n+3},x_{2n+1})\), \(n = 1, 2, \ldots\) , and \(f_{-2n}: [x_{2n+3}, x_{2n+1}) \rightarrow [x_{2n},x_{2n+2})\), \(n = 1, 2, \ldots\) . By the properties of the dual (10) we can obtain

Therefore,

Thus, we can define

f is continuous on ℝ because \(f_{2n}(x_{-2n})=x_{-2n+1}=f_{2n+2}(x_{-2n})\), \(f_{2n+1}(x_{-2n+1})=x_{-2n-2}=f_{2n+3}(x_{-2n+1})\), where \(n=0, 1, 2, \ldots \) , \(f_{1}^{-1}(x_{0}) = f_{-1}(x_{0})\), \(f_{-2n}^{-1}(x_{2n+2})=x_{2n+3}=f_{-2n-2}^{-1}(x_{2n+2})\), and \(f_{-2n+1}^{-1}(x_{2n+3})=x_{2n+2}=f_{-2n-1}^{-1}(x_{2n+3})\), where \(n=1, 2, 3, \ldots\) . we can easily check that f defined in Theorem 2.2 satisfies (4) with \(b=0\) in ℝ. In fact, if \(x\in[x_{-2n},x_{-2n+2})\), \(n=0, 1, 2, \ldots \) , \(f^{2}(x)=f_{2n+1}(f_{2n}(x))=(r_{1}+r_{2})f_{2n}(x)-r_{1}r_{2}x=(r_{1}+r_{2})f(x)-r_{1}r_{2}x\), i.e., \(f^{2}(x)-(r_{1}+r_{2})f(x)-r_{1}r_{2}x=0\). Similarly, we can also check that f satisfies (4) with \(b=0\) for \(x\in[x_{-2n+3},x_{-2n+1})\), \(x\in[x_{2n+3}, x_{2n+1})\), \(x\in[x_{2n}, x_{2n+2})\) and \(x=0\), where \(n=1, 2, 3, \ldots\) . The proof is completed. □

Remark

In the case that \(b\ne0\), as indicated in [16] for (2) therein, (4) can be reduced equivalently to the equation

the same type of equation as the one considered in Theorems 2.1 and 2.2 with vanishing b, by the replacement \(\tilde{f}(x)=f(x+\xi)-\xi\), where \(\xi=\frac{-b}{(1-r_{1})(1-r_{2})}\), if its characteristic roots \(r_{1}\), \(r_{2}\) are both real but neither of them is equal to 1. In this case solutions can be found from Theorems 2.1 and 2.2. So (4) with \(b\neq0\) can be reduced to (21) except for the case \(a=0\). For the case of \(a=0\) and \(b\neq0\), (4) has no real continuous solutions. In fact, by induction and (4) we can obtain \(f^{n}(x)=nf(x)-(n-1)x-\frac{n(n+1)}{2}b\), \(n\in\mathbb{Z}\). Furthermore, we have \(f^{n+1}(x)-f^{n}(x)=f(x)-x-(n+1)b\), \(n\in\mathbb{Z}\). For an arbitrary \(x\in\mathbb{R}\), \(f^{n+1}(x)-f^{n}(x)\) has the same sign when n takes the values N and −N, where N is a large positive integer, because f is strictly monotonic. But \(f(x)-x-(n+1)b\) has not, which contradicts the requirement \(f^{n+1}(x)-f^{n}(x)=f(x)-x-(n+1)b\), \(n\in\mathbb{Z}\).

In what follows, we consider the case that either \(a=-2\) or \(a=4\), which is not generic.

For \(a=-2\), (4) is of the form \(f^{2}(x)-3f(x)=-b\), from which we get with the replacement \(y=f(x)\): \(f(x)=3x-b\).

For \(a=4\), (4) is of the form

which is the problem of iterative roots of the linear function \(F(x):=-3x-b\). By the theory of iterative roots, as shown in [8], we know (22) has no real continuous solutions.

References

Cooke, KL, Wiener, J: Retarded differential equations with piecewise constant delays. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 99, 265-297 (1984)

Shah, SM, Wiener, J: Advanced differential equations with piecewise constant argument deviations. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 6, 671-703 (1983)

Busenberge, S, Cooke, KL: Nonlinearity and Functional Analysis. Academic Press, New York (1982)

Aftabizadeh, AR, Wiener, J, Xu, J: Oscillatory and periodic properties of delay differential equations with piecewise constant arguments. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 99, 673-679 (1987)

Gyori, I, Ladas, G: Linearized oscillations for equations with piecewise constant arguments. Differ. Integral Equ. 2, 123-131 (1989)

Wiener, J, Cooke, KL: Oscillations in systems of two differential equations with piecewise constant arguments. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 137, 221-239 (1989)

Anosov, DV: Geodesic Flows on Closed Riemannian Manifolds of a Negative Curvature. Trudy Mat. Inst. Im. V.A. Steklova, vol. 90 (1967) (Russian)

Kuczma, M, Choczewski, B, Ger, R: Iterative Functional Equations. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications, vol. 32. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1990)

Matkowski, J: Mean-type mappings and invariant curves. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 384, 431-438 (2011)

Nitecki, Z: Differentiable Dynamics: An Introduction to the Orbit Structure of Diffeomorphisms. MIT Press, London (1971)

Sternberg, S: On the behaviour of invariant curves near a hyperbolic point of a surface transformation. Am. J. Math. 77, 526-534 (1955)

Ng, CT, Zhang, W: Invariant curves for planar mappings. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 3, 147-168 (1997)

Yang, D, Zhang, W, Xu, B: Notes on a functional equation related to invariant curves. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 9, 247-255 (2003)

Matkowski, J, Zhang, W: Method of characteristic for function equations in polynomial form. Acta Math. Sin. 13, 421-432 (1997)

Yang, D, Zhang, W: Characteristic solutions of polynomial-like iterative equations. Aequ. Math. 67, 80-105 (2004)

Zhang, WM, Zhang, W: On continuous solutions of n-th order polynomial-like iterative equations. Publ. Math. (Debr.) 76, 117-134 (2010)

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the referees for their valuable comments and suggestions, which have helped to improve the quality of this paper. This work was supported by the general item (L0801) of Zhanjiang Normal University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J. Invariant curves for a delay differential equation with a piecewise constant argument. Adv Differ Equ 2015, 19 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-014-0349-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-014-0349-7