Abstract

When studying emotion and emotion regulation, typical approaches focus on intrapersonal processes. Although this emphasis clarifies what transpires within a person, it does not capture that much of emotional experience and regulation occurs between people. In this commentary, we highlight how the Cognitive-Affective Processing System (CAPS) approach—originally developed by Mischel and Shoda and extended to dyadic interactions by Zayas, Shoda, and Ayduk—can provide a unifying framework for understanding the complexity of everyday affective experiences. We discuss how this framework can be fruitfully applied to the study of emotion and emotion regulation broadly, and particularly to interpersonal emotion regulation, by considering both the mediating psychological processes within individuals, as well as the behavioral processes that transpire between individuals. To illustrate these points, we discuss some of the thought-provoking work in the special double issue on the Future of Affective Science edited by Shiota et al. (2023), and we offer forward-thinking suggestions and propose future research directions informed by the CAPS approach. By employing the CAPS framework, we can better capture the complexity of everyday affective experiences and synthesize the growing body of research in affective science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Consider two researchers—Sam and Taylor—who are working on a manuscript with a looming deadline. Both researchers experience a wide range of emotions, from excitement and pride to frustration and disappointment. To work productively towards the deadline, the researchers must manage their reactivity (i.e., how and how strongly a person responds) and continuously engage in emotion regulation (i.e., establishing, maintaining, or altering emotions and their expression; Campos et al., 1989; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Sam, who tends to be more optimistic while writing, uses various intrapersonal emotion regulation strategies to maintain a positive state, such as reframing the deadline as a challenge. Taylor, on the other hand, who tends to be more pessimistic about writing, looks to Sam for constant reassurance. When Sam uses intrapersonal emotion regulation strategies, Sam is also likely engaging in interpersonal emotion regulation. While Sam’s primary goal might be to regulate Sam’s own emotional state, Sam may also regulate Taylor’s emotional state. Regardless of Sam’s intentions, Sam’s behaviors (e.g., positive emotional expressions) are situational inputs for Taylor, acting as social signals that shape Taylor’s emotional state (Clark & Taraban, 1991; Klinnert et al., 1983). How can we capture the dynamic, continuous, and interlocked nature of affective experiences in real-life dynamics, especially when history (own and shared) has important consequences?

Despite notable progress in understanding the strategies individuals employ in regulating their emotions (Gross, 2015), researchers typically study intrapersonal processes (Campos et al., 2011). This approach does not fully capture the fact that much of affective experiences occur within social contexts involving other people (Frijda & Mesquita, 1994; Keltner & Haidt, 1999; Niedenthal & Brauer, 2012; Parkinson, 1996; van Kleef & Côté, 2022). Speaking to this point, Petrova and Gross (2023) put forth a forward-looking agenda that emphasizes the importance of widening our viewing angle to better capture interpersonal emotion regulation, which includes a “greater theoretical integration of interpersonal and non-interpersonal lines of emotion regulation research.” In our commentary, we discuss how approaches like the Cognitive-Affective Processing System (CAPS) theory (Mischel & Shoda, 1995) provide a useful framework that aligns with and supports this agenda. At their core, such frameworks allow for theoretical integration of the intertwined nature of intrapersonal and interpersonal aspects of emotion and emotion regulation. Here, we provide an overview of key ideas informed by CAPS theory. We then discuss some of the exciting work published in the special double issue in the Future of Affective Science edited by Shiota et al. (2023). We offer forward-thinking suggestions for how such ideas can generate novel future directions.

Informed by cognitive and network models, the CAPS approach conceptualizes a person’s mind as a unique network of cognitive-affective processes. Each person’s Cognitive-Affective Processing System (or “CAPS”) includes encodings and construals (of self, others, situations), affects (feelings and emotions), goals (that drive behavior towards outcomes and emotional states), beliefs (about the world like norms and values), expectancies (about outcomes and efficacy), and competencies and self-regulatory strategies (for achieving desired goals; Mischel, 1973; Mischel & Shoda, 1995, 2008, 2010; Shoda, 1999, 2004; Shoda & Mischel, 1998; Zayas & Shoda, 2009). Each person’s CAPS mediates the effect of the situation on behavior by accounting for how each person encodes, reacts, and ultimately responds to their situation.

Each person’s CAPS network remains largely stable over time and situations, but the particular cognitive-affective processes that are activated at a given moment depend on the situation. What matters is not the objective situation (e.g., the shared task of working on a manuscript) but rather what is psychologically active about the situation (see also Ellsworth & Scherer, 2003; Frijda, 1986; Manstead & Fischer, 2001; Lazarus, 1991). People can differ in their initial evaluation of situational inputs (e.g., Sam reacts less strongly than Taylor to uncertainty and novel situations). But they can also differ in their strategies to regulate emotions (e.g., Sam generally uses reappraisal, whereas Taylor tends to use distraction; John & Gross, 2007). Moreover, the same person can also behave differently—e.g., due to reactivity or preferred strategy—depending on the situation (e.g., Sam is better able to engage in reappraisal when under low stress but fails to do so under high stress; Troy et al., 2013). In this way, CAPS is a person × situation interactionist approach that provides a framework for understanding both between person differences and within individuals.Footnote 1

We focus on the CAPS approach because of its emphasis on psychological mediators that are highly relevant for emotion, emotion regulation, and interpersonal processes (see Ayduk & Mendoza-Denton, 2021; Shoda et al., 2013; Zayas et al., 2021, for applications). We note that other researchers have championed the importance of taking such interactionist approaches. For example, Barrett (2022) argues that contextual factors create a complex web of interactions that give rise to mental events, actions, and psychological meaning that cannot be understood by examining individual components in isolation because they interact non-linearly and produce outcomes probabilistically. Similarly, Doré et al. (2016) have proposed a framework that considers emotion regulation as an interaction of person, situation, and strategy. Doré and colleagues (2016) emphasize that such approaches are necessary to be able to “predict for particular people, in particular situations, which emotion regulation strategies will be most beneficial.”

A key assumption of interactionist approaches is that behavior is intricately connected to the situation that a person is in. But how do we conceptualize a “situation”? By extending the CAPS approach to social interactions, we can conceptualize each interaction partner’s behavior as the situational inputs for the other members present (Zayas et al., 2002). Thus, a dyadic interaction can be seen as the “interlocking” of two individuals’ CAPS. By understanding how each member of the dyad responds to the other’s behaviors, we can illuminate how the dyad operates as an interpersonal emotion regulation system, as well as the intricate connections between intrapersonal and interpersonal emotion regulation (Shoda et al., 2002; Zayas et al., 2002; Zayas et al., 2015). These ideas have several implications for affective science.

First, to the extent that interpersonal patterns are repeated over time, they become internalized as mental representations in a person’s CAPS (Bowlby, 1973; Campos et al., 2018; Holodynski & Kärtner, 2023; Main et al., 1985; Sbarra & Hazan, 2008); thus, interpersonal emotion regulation can become realized intrapersonally (Lee et al., 2024; Zayas et al., in press). Going back to our example of the two researchers, Taylor may develop emotion regulation scripts that take the form of if stressed or upset about writing, then seek support from Sam. Taylor may also develop expectancies; to the extent that such bids for support are effective, Taylor will also develop the expectation that takes the form of if obtain support from Sam, then experience affective relief (see also Waters & Waters, 2006). Eventually, it is possible that simply seeing Sam would provide a sense of calmness and a positive outlook (Selcuk et al., 2012). Moreover, it is possible that Sam will also develop expectations. If Sam’s own emotion regulation attempts positively impact Taylor, then Sam may be more likely to enact reappraisal in the future, resulting in automatic emotion regulation (Mauss et al., 2007).

Second, to the extent that in dyadic interaction, one person’s situation is the other person’s behavior, then a person’s affective experience, including the emotions experienced and emotion regulation strategies used, will depend on who they are interacting with. If Taylor interacts with Sam, who engages in reappraisal, Taylor’s own positive mood and goal-relevant behaviors are maintained. On the other hand, if Taylor interacts with another colleague who also feels daunted by a looming deadline, Taylor’s affective experience and behaviors will differ.

To demonstrate the CAPS approach’s utility, we discuss work from the special double issue and offer suggestions for future directions.

Shore et al. (2023), using a prisoner’s dilemma game in dyads, found that the partner’s regulation of positive expressions and the actor’s perception of this regulation both significantly increased the probability of subsequent actor cooperation, even after controlling for prior defection. These results illustrate the dynamic interplay between situational cues (partner’s positive regulation) and individual perceptions (actor’s perception of the regulation) in shaping cooperative behavior, aligning with the present CAPS framework’s emphasis on the dyadic system (Shoda et al., 2002; Zayas et al., 2002; Zayas et al., 2015). An interesting possibility for future work on interpersonal emotion regulation might be to examine how actors make sense of their partner’s emotion regulation efforts, including their partner’s initial reactivity, and when do they lead to benign inferences or mistrust.

A promising route for future work is to apply a CAPS lens to often-used and emerging tasks in affective science described in the special double issue, such as in psychophysiology (e.g., Qaiser et al., 2023), ambulatory sensing (e.g., Hoemann et al., 2023), and daily diaries (e.g., Tran et al., 2023). For instance, Hoemann et al. (2023) present a biologically triggered, idiographic experience sampling method. Replicating previous research, a key finding is that the same emotion word can correspond to different physiological responses and affect ratings (Hoemann et al., 2020; see also Campos et al., 2004). Their multimodal ambulatory sensing method is particularly suited for if… then… analysis. For example, researchers could also assess the features of psychological “situations” participants find themselves in, alongside assessing the emotions that individuals are experiencing. This includes examining their goals, motivations, and norms, as well as who they are with, during different sampled moments (Tamir & Hu, 2024; Tamir et al., 2020; Vishkin & Tamir, 2023). By analyzing these psychological ingredients, we can more precisely examine how emotional experience is shaped by interpersonal factors. Future work might recruit dyads or groups of friends and use this method to assess emotion contagion, synchrony, and interpersonal emotion regulation.

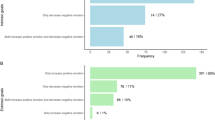

Similarly, Tran et al. (2023) sampled participants “in the wild” and conducted two daily diary studies. Participants reported having both self-focused (i.e., changing own emotions) and other-focused (i.e., changing other’s emotions) emotion regulation motivations in approximately one in five of the recorded social interactions. Future work could collect more information about the situation, such as who the interaction partner was, what the topic of the interaction was, how long the interaction lasted, how personally significant the topic was, and how well the conversation went. This information could then be used to identify psychological features of “significant social interactions” and how certain psychological features covary with self-focused and other-focused emotion regulation motivations. For example, perhaps people are more likely to report having self-focused and other-focused emotion regulation motivations in private and more intimate settings and topics, or with those who are closer. After identifying potential psychological ingredients, work could then experimentally manipulate situations people are in to obtain causal evidence.

The CAPS approach can also take work that has been primarily focused on intrapersonal processes to an interpersonal context. For example, Becker and Bernecker (2023) highlight the role of hedonic goal pursuit in self-control and self-regulation. Given that self-control varies across situations (e.g., financial, relational; Weber et al., 2002), future work could examine how the strategies people use might differ based on their own reactivity (e.g., towards temptations) and the perceived difficulty of the situation, even if hedonic goals stand in the direct service of long-term goals. The same amount of objective temptation may elicit different strategies depending on the individual’s reactivity and situational context, particularly when considering how these dynamics play out in social contexts.

Taken together, the CAPS approach provides a framework for understanding the dynamic and complex nature of affective experiences. As researchers have long acknowledged, the boundary between intrapersonal and interpersonal emotion regulation is fuzzy (Campos et al., 2004; Petrova & Gross, 2023; Zaki & Williams, 2013). By modeling the mind as a network of cognitions and affects that mediate the impact of situations on behavior, and by considering how in dyadic interactions, two such minds are intertwined, the field will better capture both intrapersonal and interpersonal aspects of emotion and emotion regulation. This approach will refine theoretical models, enabling them to represent the intricate dynamics of everyday affective experiences and inform future research in the field.

References

Ayduk, Ö., & Mendoza‑Denton, R. (2021). A cognitive–affective processing system approach to personality dispositions: Rejection sensitivity as an illustrative case study. In O. P. John & R. W. Robins (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (4th ed., pp. 411–425). The Guilford Press.

Barrett, L. F. (2022). Context reconsidered: Complex signal ensembles, relational meaning, and population thinking in psychological science. American Psychologist, 77(8), 894–920. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001054

Becker, D., & Bernecker, K. (2023). The role of hedonic goal pursuit in self-control and self-regulation: Is pleasure the problem or part of the solution? Affective Science, 4(3), 470–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-023-00193-2

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Separation: Anxiety and anger, (vol. 2). Basic Books.

Campos, J. J., Campos, R. G., & Barrett, K. C. (1989). Emergent themes in the study of emotional development and emotion regulation. Developmental Psychology, 25(3), 394–402. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.25.3.394

Campos, J. J., Camras, L. A., Lee, R. T., He, M., & Campos, R. G. (2018). A relational recasting of the principles of emotional competence. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15(6), 711–727. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2018.1502921

Campos, J. J., Frankel, C. B., & Camras, L. (2004). On the nature of emotion regulation. Child Development, 75(2), 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00681.x

Campos, J. J., Walle, E. A., Dahl, A., & Main, A. (2011). Reconceptualizing emotion regulation. Emotion Review, 3(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073910380975

Clark, M. S., & Taraban, C. (1991). Reactions to and willingness to express emotion in communal and exchange relationships. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 27(4), 324–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(91)90029-6

Doré, B. P., Silvers, J. A., & Ochsner, K. N. (2016). Toward a personalized science of emotion regulation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(4), 171–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12240

Ellsworth, P. C., & Scherer, K. R. (2003). Appraisal processes in emotion. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 572–595). Oxford University Press.

Frijda, N. H., & Mesquita, B. (1994). The social roles and functions of emotions. In S. Kitayama & H. R. Markus (Eds.), Emotion and culture: Empirical studies of mutual influence (pp. 51–87). American Psychological Association.

Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge University Press.

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

Hoemann, K., Khan, Z., Feldman, M. J., Nielson, C., Devlin, M., Dy, J., Barrett, L. F., Wormwood, J. B., & Quigley, K. S. (2020). Context-aware experience sampling reveals the scale of variation in affective experience. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 12459. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69180-y

Hoemann, K., Wormwood, J. B., Barrett, L. F., & Quigley, K. S. (2023). Multimodal, idiographic ambulatory sensing will transform our understanding of emotion. Affective Science, 4(3), 480–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-023-00206-0

Holodynski, M., & Kärtner, J. (2023). Parental coregulation of child emotions. In I. Roskam, J. J. Gross, & M. Mikolajczak (Eds.), Emotion regulation and parenting (pp. 129–148). Cambridge University Press.

John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Individual differences in emotion regulation. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of Emotion Regulation (pp. 351–372). The Guilford Press.

Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (1999). Social functions of emotions at four levels of analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 13(5), 505–521.

Klinnert, M. D., Campos, J. J., Sorce, J., Emde, R. N., & Svejda, M. (1983). Emotions as behavior regulators: Social referencing in infancy. In R. Plutchik, & H. Kellerman (Eds.), Emotion: Theory, research, and experience (Vol. 2, pp. 57–86). Academic Press

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press.

Lee, R. T., Surenkok, G., & Zayas, V. (2024). Mitigating the affective and cognitive consequences of social exclusion: An integrative data analysis of seven social disconnection interventions. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 1250. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18365-5

Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1–2), 66–104. https://doi.org/10.2307/3333827

Manstead, A. S. R., & Fischer, A. H. (2001). Social appraisal: The social world as object of and influence on appraisal processes. In K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr, & T. Johnstone (Eds.), Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research (pp. 221–232). Oxford University Press.

Mauss, I. B., Bunge, S. A., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Automatic emotion regulation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1(1), 146–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00005.x

Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (2008). Toward a unified theory of personality: Integrating dispositions and processing dynamics within the cognitive-affective processing system. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (3rd ed., pp. 208–241). The Guilford Press.

Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (2010). The situated person. In B. Mesquita, L. F. Barrett, & E. R. Smith (Eds.), The mind in context (pp. 149–173). The Guilford Press.

Mischel, W. (1973). Toward a cognitive social learning reconceptualization of personality. Psychological Review, 80(4), 252–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0035002

Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1995). A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review, 102(2), 246–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.246

Niedenthal, P. M., & Brauer, M. (2012). Social functionality of human emotion. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 259–285. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131605

Parkinson, B. (1996). Emotions are social. British Journal of Psychology, 87(4), 663–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1996.tb02615.x

Petrova, K., & Gross, J. J. (2023). The future of emotion regulation research: Broadening our field of view. Affective Science, 4(4), 609–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-023-00222-0

Qaiser, J., Leonhardt, N. D., Le, B. M., Gordon, A. M., Impett, E. A., & Stellar, J. E. (2023). Shared hearts and minds: Physiological synchrony during empathy. Affective Science, 4(4), 711–721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-023-00210-4

Rothbart, M. K., & Bates, J. E. (2006). Temperament. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 99–166). Wiley Inc.

Sbarra, D. A., & Hazan, C. (2008). Coregulation, dysregulation, self-regulation: An integrative analysis and empirical agenda for understanding adult attachment, separation, loss, and recovery. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(2), 141–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868308315702

Selcuk, E., Zayas, V., Günaydin, G., Hazan, C., & Kross, E. (2012). Mental representations of attachment figures facilitate recovery following upsetting autobiographical memory recall. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(2), 362–378. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028125

Shiota, M. N., Camras, L. A., & Adolphs, R. (2023). The future of affective science: Introduction to the special issue. Affective Science, 4(3), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-023-00220-2

Shoda, Y. (1999). A unified framework for the study of behavioral consistency: Bridging person × situation interaction and the consistency paradox. European Journal of Personality, 13(5), 361–387. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0984(199909/10)13:5%3c361::AID-PER362%3e3.0.CO;2-X

Shoda, Y. (2004). Individual differences in social psychology: Understanding situations to understand people, understanding people to understand situations. In C. Sansone, C. C. Morf, & A. T. Panter (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Methods in Social Psychology (pp. 117–141). Sage Publications Inc.

Shoda, Y., & Mischel, W. (1998). Personality as a stable cognitive-affective activation network: Characteristic patterns of behavior variation emerge from a stable personality structure. In S. J. Read, & L. C. Miller (Eds.), Connectionist models of social reasoning and social behavior (pp. 175–208). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers

Shoda, Y., LeeTiernan, S., & Mischel, W. (2002). Personality as a dynamical system: Emergence of stability and constancy from intra- and inter-personal interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(4), 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0604_06

Shoda, Y., Wilson, N. L., Chen, J., Gilmore, A., & Smith, R. E. (2013). Cognitive-affective processing system analysis of intra-individual dynamics in collaborative therapeutic assessment: Translating basic theory and research into clinical applications. Journal of Personality, 81(6), 554–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12015

Shore, D., Robertson, O., Lafit, G., & Parkinson, B. (2023). Facial regulation during dyadic interaction: Interpersonal effects on cooperation. Affective Science, 4(3), 506–516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-023-00208-y

Tamir, M., & Hu, D. (2024). Emotional goals. In J. J. Gross & B. Q. Ford (Eds.), Handbook of emotion regulation (3rd ed., pp. 258–264). The Guilford Press

Tamir, M., Vishkin, A., & Gutentag, T. (2020). Emotion regulation is motivated. Emotion, 20(1), 115–119. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000635

Tran, A., Greenaway, K. H., Kostopoulos, J., O’Brien, S. T., & Kalokerinos, E. K. (2023). Mapping interpersonal emotion regulation in everyday life. Affective Science, 4(4), 672–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-023-00223-z

Troy, A. S., Shallcross, A. J., & Mauss, I. B. (2013). A person-by-situation approach to emotion regulation: Cognitive reappraisal can either help or hurt, depending on the context. Psychological Science, 24(12), 2505–2514. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613496434

van Kleef, G. A., & Côté, S. (2022). The social effects of emotions. Annual Review of Psychology, 73, 629–658. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-020821-010855

Vishkin, A., & Tamir, M. (2023). Emotion norms are unique. Affective Science, 4(3), 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-023-00188-z

Walle, E. A., & Dukes, D. (2023). We (still!) need to talk about valence: Contemporary issues and recommendations for affective science. Affective Science, 4(3), 463–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-023-00217-x

Waters, H. S., & Waters, E. (2006). The attachment working models concept: Among other things, we build script-like representations of secure base experiences. Attachment and Human Development, 8(3), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730600856016

Weber, E. U., Blais, -R., & Betz, N. E. (2002). Domain-specific risk-attitude scale: Measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. Journal Behavioral Decision Making, 15, 263–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.414

Zaki, J., & Williams, W. C. (2013). Interpersonal emotion regulation. Emotion, 13(5), 803–810. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033839

Zayas, V., & Shoda, Y. (2009). Three decades after the personality paradox: Understanding situations. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(2), 280–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.03.011

Zayas, V., Günaydin, G., & Shoda, Y. (2015). From an unknown other to an attachment figure: How do mental representations change as attachments form? In V. Zayas, & C. Hazan (Eds.), Bases of adult attachment: Linking brain, mind and behavior (pp. 157–183). Springer Science + Business Media

Zayas, V., Lee, R. T., & Shoda, Y. (2021). Modeling the mind: Assessment of if … then … profiles as a window to shared psychological processes and individual differences. In D. Wood, S. J. Read, P. D. Harms, & A. Slaughter (Eds.), Measuring and modeling persons and situations (pp. 145–192). Elsevier Academic Press

Zayas, V., Shoda, Y., & Ayduk, O. N. (2002). Personality in context: An interpersonal systems perspective. Journal of Personality, 70(6), 851–900. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.05026

Zayas, V., Urgancı, B., & Strycharz, S. (in press). Out of sight but in mind: Experimentally activating partner representations in daily life buffers against common stressors. Emotion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work received support from a Cornell Provost Diversity Fellowship awarded to Randy T. Lee and U.S. National Science Foundation awards 1749554 and 2234932 granted to Vivian Zayas. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cornell University or the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ Contributions

RTL developed the original concept for the article, wrote all drafts, and solicited and integrated feedback from all authors. MN, WMF, and IR contributed to the article’s conception and editing. YS provided theoretical input, editing, and critical review. VZ provided theoretical direction, editing, additional writing, and project supervision. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Additional information

Handling editor: Michelle Shiota

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, R.T., Ni, M., Fang, W.M. et al. An Integrative Framework for Capturing Emotion and Emotion Regulation in Daily Life. Affec Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-024-00262-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-024-00262-0