Abstract

Emotion norms shape the pursuit, regulation, and experience of emotions, yet much about their nature remains unknown. Like other types of social norms, emotion norms reflect intersubjective consensus, vary in both content and strength, and benefit the well-being of people who adhere to them. However, we propose that emotion norms may also be a unique type of social norm. First, whereas social norms typically target behaviors, emotion norms can target both expressive behavior and subjective states. Second, whereas it may be possible to identify universally held social norms, norms for emotions may lack any universality. Finally, whereas social norms are typically stronger in more collectivist cultures, emotion norms appear to be stronger in more individualist cultures. For each of the potentially distinct features of emotion norms suggested above, we highlight new directions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Much like a fish does not know it is wet, people can fail to recognize their emotions are shaped by the social context. Yet social context is the ether in which emotional experiences unfold (Mesquita et al., 2017; Parkinson et al., 2005). In many social contexts, an inter-subjective consensus develops regarding which emotions are or are not experienced or expressed, and which emotions should or should not be experienced or expressed. Such inter-subjective consensus comprises emotion norms. In this article, we first introduce emotion norms as a type of social norm. Next, we propose features that may render emotion norms unique. Finally, we highlight open questions for future research.

Emotion Norms as a Type of Social Norm

Emotion norms are a type of social norm. First, social norms contain an intersubjective consensus regarding which behaviors are or are not common or appropriate (Gelfand & Jackson, 2016). Likewise, emotion norms reflect an intersubjective consensus regarding which emotions are or are not experienced or expressed in one’s society (descriptive norms), and which emotions should or should not be experienced or expressed in one’s society (normative or injunctive norms; Cialdini et al., 1990). These norms are a cognitive representation of what is common or appropriate in a social group. Such norms can inform motivation but are distinct from it. For instance, emotion norms can spawn congruent emotion goals, such as wanting to not feel angry if one perceives a norm against anger (Briggs, 1970), but they can also spawn incongruent emotion goals, such as wanting to feel guilty if one perceives a norm of not feeling guilty among one’s group for a past transgression it committed (Goldenberg et al., 2014).

Second, social norms vary independently in content and strength (Vishkin & Kitayama, 2023a). Content refers to behavior that the norm encourages or discourages (e.g., whether or not people recycle, or are expected to recycle), and strength refers to the relative importance and injunctive power of the norm (e.g., how important is it for people to adhere to the recycling norm). With respect to emotion norms, research has focused primarily on their content, by comparing mean levels of different emotions between cultural groups. Such research has found, for instance, that socially-engaging emotions are more valued in collectivist cultures, whereas socially-disengaging emotions are more valued in individualist cultures (Kitayama et al., 2006). As another example, compared to East Asians, European Americans are more likely to value excitement and less likely to value calmness (Tsai, 2007). However, similar to social norms, there is more to emotion norms than their mean levels. The same norm can be weaker or stronger in different social groups, independent of its mean level. For instance, Americans value calmness at more moderate levels than East Asians, but they might have a stronger norm for valuing calmness at that particular level.

Finally, adherence to social norms predicts higher well-being and deviation from them predicts lower well-being (Stavrova & Luhmann, 2016; Stavrova et al., 2013). Similarly, adherence to emotion norms and deviation from them carry implications for well-being (Bastian et al., 2014; Tsai et al., 2006). For example, perceiving an inter-subjective consensus against feeling negative emotions leads people to feel more negative emotion due to the negative self-evaluations people have when experiencing undesired emotions (Bastian et al., 2012). In summary, like other social norms, emotion norms are complex social phenomena that carry important implications for healthy functioning.

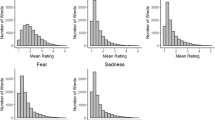

Social norms in general, and emotions norms in particular, are commonly measured through a variety of methods. The content of emotion norms across cultures has been measured via mean levels of emotions judged as appropriate (Senft et al., 2023) or personally valued (e.g., Tsai et al., 2006). The strength of emotion norms has been assessed by measures of homogeneity and dispersion, including heterogeneity across class membership in latent class analysis (Eid & Diener, 2001), standard deviations (Vishkin et al., 2023), and concordance with the average emotional profile in one’s country (emotion concordances; Vishkin et al., 2023).Footnote 1 The measures of norm strength capture different aspects: measures of homogeneity capture adherence to a norm for each emotion in a given set of emotion terms, whereas measures of concordance capture the relative prioritization of each emotion in a given set of emotion terms (see Fig. 1 in Vishkin et al., 2023). Also, some of the measures assessing content and strength are associated with each other and therefore should be disentangled. In particular, standard deviations (used for assessing strength) are smaller as means (used for assessing content) are more extreme, and therefore when using one of these measures one should ideally control for the other measure.

Unique Features of Emotion Norms

Although they are a type of social norm, we propose that emotion norms may be distinct from other social norms in their scope, variability, and variation across cultures.

Scope

Emotions involve subjective, physiological, and behavioral (or expressive) components (Frijda, 1988; Mauss & Robinson, 2009). Norms for emotions can apply to any of these components. Emotion norms can apply to expression (e.g., you should smile) and to experience (e.g., you should be happy). This contrasts with norms for behaviors, such as reciprocity and cooperation in social interactions, which appear to apply to the external manifestation of a behavior, and not necessarily to the intention to commit the behavior (Bicchieri, 2006).

The different targets of emotion norms can be, but are not always, aligned. For instance, in accordance with gendered emotion norms, women are more likely than men to experience sadness and to express sadness, such as by crying (Fischer et al., 2004). Instances where these facets are not aligned have been studied in organizational research on emotional labor—the process of publicly displaying emotions which are aligned with emotion norms in one’s organization (Hochschild, 1983; Rafaeli & Sutton, 1987). Organizational norms might apply to the expression of emotions (when workers interact with customers) but not to the experience of emotions (Grandey, 2003; Hochschild, 1983). Adherence to norms for expression without concomitant change in experience results in surface acting, which is an effortful process reliably associated with burnout and lower well-being (Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011). However, adherence to norms for expression with concomitant change in experience, known as deep acting, does not necessarily lead to burnout or lower well-being (Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011).

Variability

Some norms for behaviors are culturally variable, but it is possible to identify behaviors which are universally considered norm-violating, such as hoarding shared resources (Eriksson et al., 2021). Are there emotions which are universally considered to be norm-violating? Obvious candidates from American culture, such as happiness and sadness, are not universal. For instance, there is a strong positive norm for happiness in the USA, but other cultures do not necessarily share it (Joshanloo & Weijers, 2014). Meanwhile, there is a norm against sadness in the USA, while in other cultures sadness is viewed more favorably (Chentsova-Dutton et al., 2014). Presently, it is unclear if there is a universally held emotion norm— and if such a norm exists, it is yet to be identified. Furthermore, emotion norms can prescribe not just which emotions are good or bad, but which level of intensity is desired for these emotions. For instance, a norm might ascribe a moderate level of happiness, where both high and low levels of happiness would be considered non-normative. Social norms that target behaviors typically prescribe which behaviors are good or bad, but not necessarily the intensity with which such behaviors should be performed. For instance, there may be norms against eating insects in some cultures and norms in favor of eating insects in other cultures (Jensen & Lieberoth, 2019), but we are unaware of norms in favor of eating a moderate amount of insects, to the exclusion of eating many and eating no insects.Footnote 2 Thus, relative to other social norms, emotion norms may be more variable both in their lack of universality and in their level of intensity.

Variation Across Cultures

Adherence to social norms for behaviors is greater in cultures higher in collectivism (Bond & Smith, 1996) and tightness (Gelfand et al., 2011). Conversely, there is some evidence that adherence to norms for experienced emotions may be greater in more individualist cultures (Eid & Diener, 2001; Vishkin & Kitayama, 2023b; Vishkin et al., 2023) and is unrelated to tightness-looseness (Vishkin & Kitayama, 2023b; Vishkin et al., 2023). These findings extend to norms for expressed emotions (Matsumoto et al., 2008), wherein endorsement of display rules appears to be more homogenous in more individualist cultures. One explanation for such findings is that people in individualist cultures are more attuned to their subjective states (Markus & Kitayama, 1991), including emotions, and therefore develop stronger norms for them.

One consequence of these associations is that deviation from emotion norms predicts lower well-being in more individualist cultures (Vishkin et al., 2023). Similarly, the demands of emotional labor in the workplace might take a greater toll on well-being in more individualist cultures. Indeed, a meta-analysis has linked emotional labor to greater emotional exhaustion, and has shown that this link is stronger in more individualist cultures (Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011). For instance, adherence to expressive emotion norms leads to emotional labor, and emotional labor can lead to burnout. However, the latter link has been observed among American, but not Chinese, service workers (Allen et al., 2014). Together, existing findings demonstrate that, contrary to other types of social norms, adherence to experienced and expressed emotion norms appears to be greater in more individualist cultures, and deviation from emotion norms may carry more negative implications for well-being in such cultures.

Future Directions and Conclusions

Norms can play a crucial role in shaping behaviors and their downstream social implications. For instance, how individuals treat minority groups hinges heavily on social norms regarding how to acknowledge and treat such groups (e.g., Pauker et al., 2015). Norms can also play a crucial role in shaping emotions and their downstream social implications. For instance, how individuals react to expressions of negative emotions can hinge on social norms regarding such emotions. Yet, we presently know relatively little about such norms and their potential effects. The future of emotion science can overcome this limitation by assessing emotion norms more systematically, identifying factors that contribute to their development, and examining their social implications. The unique features highlighted above point to additional new research directions. First, regarding scope, what is the interplay between norms for emotion expression and norms for emotion experience? They might vary independently in some social units (e.g., organizations), but co-vary in other social units (e.g., cultures). Second, regarding variability, is it possible to identify universally held emotion norms? Future work can address this question by mapping the range of norms for discrete emotions across cultures. Third, regarding cultural associations, how and why is adherence to emotion norms greater in more individualist cultures? This question is intriguing given the cultural directive in individualist cultures to be unique (Kim & Markus, 1999), which suggests that adherence to norms should be universally weaker in more individualist cultures. Considering emotion norms as a unique type of social norm reveals novel insights into the social processes that shape emotions and how emotions, in turn, can shape us.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Change history

24 May 2023

The title of the article is repeated as a heading above the first paragraph.

Notes

Some exceptions might exist, such as the norm for moderate consumption of alcohol in some cultures (Hanson, 1995), to the exclusion of both abstinence and binge-drinking.

References

Allen, J. A., Diefendorff, J. M., & Ma, Y. (2014). Differences in emotional labor across cultures: A comparison of Chinese and U.S. service workers. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9288-7

Bastian, B., Kuppens, P., Hornsey, M. J., Park, J., Koval, P., & Uchida, Y. (2012). Feeling bad about being sad: The role of social expectancies in amplifying negative mood. Emotion, 12(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024755

Bastian, B., Kuppens, P., De Roover, K., & Diener, E. (2014). Is valuing positive emotion associated with life satisfaction? Emotion, 14(4), 639–645. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036466

Bicchieri, C. (2006). The grammar of society: The nature and dynamics of social norms. Cambridge University Press.

Bond, R., & Smith, P. B. (1996). Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Asch’s (1952b, 1956) line judgment task. Psychological Bulletin, 119(1), 111–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.111

Briggs, J. L. (1970). Never in anger: Portrait of an Eskimo family. Harvard University Press.

Chentsova-Dutton, Y. E., Senft, N., & Ryder, A. G. (2014). Listening to negative emotions: How culture constrains what we hear. In W. G. Parrott (Ed.), The positive side of negative emotions (pp. 146–178). Guilford Press.

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015–1026. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015

De Leersnyder, J. (2017). Emotional acculturation: A first review. Current Opinion in Psychology, 17, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.06.007

De Leersnyder, J., Mesquita, B., & Kim, H. S. (2011). Where do my emotions belong? A study of immigrants’ emotional acculturation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(4), 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211399103

Eid, M., & Diener, E. (2001). Norms for experiencing emotions in different cultures: Inter- and intranational differences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(5), 869–885. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.81.5.869

Eriksson, K., Strimling, P., Gelfand, M., Wu, J., Abernathy, J., Akotia, C. S., Aldashev, A., Andersson, P. A., Andrighetto, G., Anum, A., Arikan, G., Aycan, Z., Bagherian, F., Barrera, D., Basnight-Brown, D., Batkeyev, B., Belaus, A., Berezina, E., Björnstjerna, M., … Van Lange, P. A. M. (2021). Perceptions of the appropriate response to norm violation in 57 societies. Nature Communications, 12(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21602-9

Fischer, A. H., Rodriguez Mosquera, P. M., van Vianen, A. E. M., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2004). Gender and culture differences in emotion. Emotion, 4(1), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.4.1.87

Frijda, N. H. (1988). The laws of emotion. The American Psychologist, 43(5), 349–358. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3389582

Gelfand, M. J., Raver, J. L., Nishii, L., Leslie, L. M., Lun, J., Lim, B. C., ..., & Yamaguchi, S. (2011). Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science, 332, 1100–1104.

Gelfand, M. J., & Jackson, J. C. (2016). From one mind to many: The emerging science of cultural norms. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.11.002

Goldenberg, A., Saguy, T., & Halperin, E. (2014). How group-based emotions are shaped by collective emotions: Evidence for emotional transfer and emotional burden. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(4), 581–596. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037462

Grandey, A. A. (2003). When “the show must go on”: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal, 46(1), 86–96.

Hanson, D. J. (1995). Preventing alcohol abuse: Alcohol, culture, and control. Praeger.

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. University of California Press.

Hülsheger, U. R., & Schewe, A. F. (2011). On the costs and benefits of emotional labor: A meta-analysis of three decades of research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(3), 361–389. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022876

Jensen, N. H., & Lieberoth, A. (2019). We will eat disgusting foods together—Evidence of the normative basis of Western entomophagy-disgust from an insect tasting. Food Quality and Preference, 72, 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.08.012

Joshanloo, M., & Weijers, D. (2014). Aversion to happiness across cultures: A review of where and why people are averse to happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 717–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9489-9

Kim, H., & Markus, H. R. (1999). Deviance or uniqueness, harmony or conformity? A cultural analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(4), 785–800. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.77.4.785

Kitayama, S., Mesquita, B., & Karasawa, M. (2006). Cultural affordances and emotional experience: Socially engaging and disengaging emotions in Japan and the United States. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 890–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.890

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., Fontaine, J., Angus-Wong, A. M., Arriola, M., Ataca, B., & Bond, M. H. (2008). Mapping expressive differences around the world: The relationship between emotional display rules and individualism versus collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022107311854

Mauss, I. B., & Robinson, M. D. (2009). Measures of emotion: A review. Cognition & Emotion, 23(2), 209–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930802204677

Mesquita, B., Boiger, M., & De Leersnyder, J. (2017). Doing emotions: The role of culture in everyday emotions. European Review of Social Psychology, 28(1), 95–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2017.1329107

Parkinson, B., Fischer, A. H., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2005). Emotion in social relations: Cultural, group, and interpersonal processes. Psychology Press.

Pauker, K., Apfelbaum, E. P., & Spitzer, B. (2015). When societal norms and social identity collide: The race talk dilemma for racial minority children. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(8), 887–895. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615598379

Rafaeli, A., & Sutton, R. I. (1987). Expression of emotion as part of the work role. Academy of Magagement Review, 12(1), 23–37.

Senft, N., Doucerain, M. M., Campos, B., Shiota, M. N., & Chentsova-Dutton, Y. E. (2023). Within- and between-group heterogeneity in cultural models of emotion among people of European, Asian, and Latino Heritage in the United States. Emotion, 23(1), 1–14.

Stavrova, O., & Luhmann, M. (2016). Are conservatives happier than liberals? Not always and not everywhere. Journal of Research in Personality, 63, 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.04.011

Stavrova, O., Fetchenhauer, D., & Schlösser, T. (2013). Why are religious people happy? The effect of the social norm of religiosity across countries. Social Science Research, 42(1), 90–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.07.002

Tsai, J. L. (2007). Ideal affect: Cultural causes and behavioral consequences. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2(3), 242–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00043.x

Tsai, J. L., Knutson, B., & Fung, H. H. (2006). Cultural variation in affect valuation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 288–307. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.2.288

Vishkin, A., & Kitayama, S. (2023a). Two Aspects of Social Norm Adherence – Willingness to Punish Norm Violators and a More Limited Range of Appropriate Behaviors – Disocciate Across Cultures. Manuscript under Review.

Vishkin, A., & Kitayama, S. (2023b). Emotion Concordance is Higher among Immigrants from More Individualist Cultures: Implications for Emotion Acculturation. Manuscript under review.

Vishkin, A., Kitayama, S., Berg, M. K., Diener, E., Gross-Manos, D., Ben-Arieh, A., & Tamir, M. (2023). Adherence to emotion norms is greater in individualist cultures than in collectivist cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000409

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anat Rafaeli for comments on a previous version of this manuscript. The second author acknowledges support of Israel Science Foundation grant #2281/20, and the Artery Chair in Personality Studies Endowed by Goldberg, Geller and Luria.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

Not applicable.

Additional information

Handling editor: Linda Camras

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.