Abstract

Authors discuss the topic of inclusion process in academic education from a semiotic and dynamic perspective. Inclusive experience in educational and academic context is constructed through the personalization of the processes of sensemaking within a wider cultural and shared social context. Authors have implemented an innovative tool for a qualitative research about sensemaking processes. They create the upside down world narrative methodology, namely, a double task of narrating one’s own experience in two times, asking participants to turn upside down their narration. Such a device allows grasping the inherent and constitutive ambivalence of each psychological process of sensemaking. Results of semiotic narrative analysis show that inclusion appears narratively articulated on two broadly generalized domains of sense as follows: the relationship with others and the training path.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The interest in academic inclusion is a current and central issue for every institution that aims to ensure a serene and productive path of all those in academic education. This insertion is aimed at making possible the acquisition, the updating, and the development of professional skills (to be understood as adaptable, renewable, and transformable throughout the entire lifetime span) essential and necessary to boost those areas of great centrality and interest in the current cultural and social discourse as follows: employability, social integration, active citizenship, and personal fulfillment (Valerio et al. 2013).

In Italy, the centrality of this commitment has been recognized over time by many national and European legislative amendments (Freda et al. 2010; Valerio et al. 2013) which intend to protect the academic education of those weak categories of students (e.g., with different forms of disability, in disadvantaged conditions, or simply undergoing a momentary phase of discomfort) that encounter a greater burden of difficulties and obstacles in the performance of university practices.

It should be noted that the demand for university education is a diversified demand, made up of multiple needs of users, as subjects of law in accessing and using the educational offer. In order to avoid processes of exclusion (in the variegated forms of abandonment, marginalization, “nomadism” between the various institutions and educational institutions, etc.), the specific needs must be integrated into orderly networks of functions aimed at supporting and mediating actions without which they are resolved in substitute and subsidiary ways.

In cases of disability, for example, integrating the subject into the training circuit means recognizing her specific needs, providing support but also ensuring the equivalence of the university path. The criterion of equivalence indeed constitutes the balancing of this support, in absence of which the university function of cultural training and professionalization would be distorted towards functions of mere assistance and pure socialization (Rainone et al. 2010).

From a general point of view, the recognition of individual specificity represents therefore the concrete possibility towards the realization of the institutional tasks of elaboration of multiple personalized intervention strategies (Ianes 2005). Therefore we need human and material mediators capable of responding to the diversification of situations, needs, and abilities of the different students. Such mediators, as cultural tools, become effective in their function as mind amplifiers (Canevaro 2005) and tools for regulating the relationship between the individual, context, and planning (Rainone et al. 2010, p. 89).

In these sense, the inclusion topic has a more generalized and wider scope. In the perspective of this work, we assume that the relationship individual/context/projectuality is a semiotic process of construction of meanings (Salvatore 2016a; Valsiner 2014; De Luca Picione 2015a, 2015b, 2020a; Freda 2008). Through the intersubjective construction of meanings—by different signs and symbolic devices—people are indeed able to regulate social actions, to direct their actions, and to mediate between their individual choices and the rules of the social context (Salvatore 2016a; Valsiner 2007, 2014; Freda 2008; De Luca Picione and Freda 2012, 2014, 2016a, 2016b, 2016c). This semiotic process of construction, development, and articulation of meanings is a process that is not only confronted exclusively with the material constraints/current resources present and with physical obstacles/supports but is also articulated in the intertwining of shared and contextual cultural dimensions with the subjective positionings (affective and cognitive - De Luca Picione and Freda 2016a, 2016c; De Luca Picione and Freda 2016a; Fossa et al. 2019a; Pérez et al. 2020; Fossa et al. 2019b; Fossa et al. 2018) among other people within institutional frames.

In general terms, each person develops and regulates her own action with reference to a contextual framework through the sensemaking process of her own experience. The network of meanings that she constructs (through affective, cognitive, social, and cultural processes recursion) works as an orientation in order to organize one’s relationships and actions within the context. Recognizing the subjectivity of the person means considering the way in which he makes value and interprets her experience and the use she makes of it within a specific intersubjective context.

Therefore, implementing the inclusion process involves not only considering the specificities of the difficulties/constraints that are objectively measurable and recognizable but also understanding the ways the person transforms these circumstances into meanings that regulate and direct her actions, choices, and social relations within the university context (in her participation in formal and informal activities, in relations with teachers, peers, and services in general). This vision leads us to consider that the process of inclusion has a rather general goal, as well as in different measures and gradients pertains to all the students as subjects that are confronted at multiple levels (affective, cognitive, relational, agentive/strategic) with the training institution and with the other social actors involved in it.

Academic Inclusion within a Semiotic Psychological Perspective

Since sensemaking process of one’s own experience is always a contextual and local process of confrontation and social negotiation with multiple intertwining of meanings (De Luca Picione and Freda 2012), we point out the possibility of semantic confusion and misunderstanding, inherent in the terms of inclusion and integration.

Indeed the terms used for integration and inclusion convey the sense of unity, wholeness, and totality. Specifically, the term integration has to do with “the integral” and “integrity” (in the sense of “completing the missing part to achieve wholeness”), the inclusion has to do with “the insertion,” the “reporting of an element/part/individual within a whole/group/category.” In both meanings of the terms inclusion and integration, although there is a polysemic plurality, there is a reference to the meaning of “unity,” of “totality.”

From the spatial and logical point of view, even if in a significantly and substantially different manner, in fact the notions of integration and inclusion both address a relationship among two entities between which somehow a relation of belonging and insertion is established. If people had a two-dimensional and timeless constitution, then the representation of “being a part of something”, of “being included in a whole” would fit very satisfactorily. However, people are always struggling with development and learning processes, creating future expectations, reformulating past memories, constantly experiencing contextual changes and transformations, forming new bonds, and unraveling old relationships (De Luca Picione and Freda 2016c; De Luca Picione and Valsiner 2017; Valsiner and De Luca Picione 2017). This leads us to think that rather than having to deal only with similarity, identity, equality, unity, and wholeness, people relate and confront each other with differences, diversities, partiality, transformations, and all possible other radical forms of otherness (De Luca Picione and Valsiner 2017). The common conception of the individual as spherical (Eidelsztein 2015; De Luca Picione 2019; Heft 2013) refers to the idea of individuality as indivisibility (from the Latin etymology “in-dividuus,” “not-divisible”). This representation implies that the individual in himself is not internally divisible but is separable from the outside, from the environment. In association with this vision, the ontological difference—that a certain psychologizing vision promotes—between the internal world and the external world is supported (De Luca Picione 2020b). Hence, the possibility of incorporating the individual as a whole within a class, a whole, a category, and then group, institution, environment, etc.

In light of what has just been said, a person does not participate in her own experience contexts in terms of container/content (namely, to be contained within a container). She participates within her contexts in dialectical terms, contributing to the reading and construction of a contextual framework that offers orientation and interpretability criteria (Salvatore, 2016a; Salvatore and Freda 2011; De Luca Picione 2020b). The same sense of belonging can be read in the direction of a continuous negotiation/adhesion/re-negotiation of practices and their meanings, that is, in the direction of a semiotic process that builds changing relational forms between subject/ action/otherness/symbolic devices (Vygotsky 1978; Cole 2004; Valsiner 2007, 2014; De Luca Picione 2015a). The dynamism of this process is guaranteed by its very constitutive dialectical and dialogical nature (Marková 2003; Linell 2009; Molina et al. 2013; Molina et al. 2015).

The Oppositional Semiotic Dynamics of the Sensemaking Process

In this section, we present some basic notions, within a psychological-semiotic perspective (De Luca Picione et al. 2017, 2018; De Luca Picione 2020a, b, c; De Luca Picione et al. 2019; Salvatore, 2016a; Valsiner 2007, 2014; Neuman 2003b, 2014) on the dynamics of sensemaking processes. The construction of meaning and its expression are based on a dynamic process based on the detection of differences and the emergence of a sense through opposition (Abbey and Valsiner 2004; De Luca Picione and Valsiner 2017; De Luca Picione and Valsiner 2017; Molina and Del Río 2009).

This principle based on differentiation and opposition as the foundation of every process of meaning has a wide and consolidated diffusion in many scientific fields, from cognitive and psychological sciences to structuralist linguistic approaches to biology and semiotics (Ugazio 2013; Valsiner 2007, 2014; Assaf et al. 2015; Bateson 1979; de Saussure 1922; Greimas 1983; Sebeok 1998; Lotman 1985; Hoffmeyer 1996).

Detecting differences is the basic mechanism that generates meaning (Bateson 1979; Lotman 1985; Neuman 2003a; De Luca Picione 2020c) which allows primarily experience organization. Just think how much necessaryFootnote 1 some pairs of oppositions are as follows: first/after (past/future), inside/outside (subject/object), and me/not-me (subject/otherness) (De Luca Picione and Valsiner 2017; De Luca Picione et al. 2015; Valsiner 2014).

These differences constitute the beginning and the pillars for the construction of every possible story and its questioning as follows: time, space, and the relationship between subjects (these three aspects are at the basis of the “deictic process of indication,” see the Bühler’s theory of language, Buhler 1934).

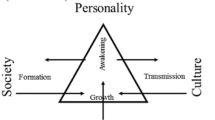

From a syntactic and semantic point of view, Algirdas Julien Greimas (1983) has carefully highlighted, in his narratological studies, how the fundamental structure of the generation of meaning is rooted in a process of basic differentiation. He argues that at the base of the processes of sensemaking, there is an oppositional process that articulates a semantic micro-universe governed by a series of fundamental differential relations (Traini 2013, p. 97). Greimas uses the semiotic square (Fig. 1) as an analysis tool for reading texts and for describing the processes of sensemaking.Footnote 2 It is based on an abstract network of relationships as follows: opposition, contradiction, and complementarity. The terms within this model are not substantially defined, but only for the relations they have with each other (Traini 2013, p. 99). It is worth to note that the semiotic square does not work only in terms of classification, but mainly in terms of construction and complexification of the syntactic processes of sense generation starting, from the basic operations of negation and affirmation. These operations according to Greimas delineate paths and designate the embryonic conditions of narrativityFootnote 3 (Traini 2013, p.105).

This model has a number of implications that are worth presenting and discussing. First, from a psychological point of view, the process of sensemaking is not a purely cognitive process and based on the principles of Aristotelian logic (considered as bulwarks of every pure form of rationality and cogito). The development of polarities finds its foundation in the affective dynamics of the subjects that differentiate and discretize different states of the world starting from the affective matrix of each cognitive process (Matte Blanco 1975; Salvatore, 2016a; Valsiner 2014; Freda 2008; De Luca Picione 2015a, De Luca Picione 2017; Tateo 2016, 2018). This discretization is based on the simultaneous activation of two types of logic, the one symmetrizing (which tends to homogenize) and the other asymmetric (which tends to detect differences and build propositional relationships) (Matte Blanco 1975; Salvatore 2014, 2016a; Salvatore and Zittoun 2011). In front of the initial construction by opposition of one’s own experience, we observe that both logics are active and cooperating. That is, we observe the emergence of different polarized categorial sets (starting from affective activation), separated from each other and therefore in an asymmetrical relationship.

According a logic of symmetrization, we have a homogenization and identity relationship between all the signs within each set, generating an equivalence between all the parts and the whole (Matte Blanco 1975).

We want to discuss an implication of this point. There are primary basic polarizations that are founded on affective and bodily process as follows: pleasure/displeasure, active/passive, and inner/outer (Salvatore et al. in press). Yet, we note that many secondarily semantic polarizations do not have a universal, stable, lasting character. They are not absolute, although somehow already proposed by their own cultural repertory of belonging. Therefore, we are saying that each one informs her own field of experience through an idiosyncratic process of opposition, given by local and contingent interaction with other people. According to this, for example, the opposite of “good” does not coincide for all people with “bad,” but can find multiple forms such as “bad,” “unpleasant,” “selfish,” “unfair,” “bitter,” “disagreeable,” and so on. The examples that can be done are endless, but this discussion finds its basic principle in the idea that people define and discretize their experience through linguistic categories (Barrett 2006), using them however not only according to the rules and prescriptions of their own code and linguistic system (according to a logic of correctness and consistency, such as that of any dictionary) but through the continuous and innovative fusion of a cultural and subjective positioning in local and contingent interactions with the others.

Another point is at stake. We observe that the polarization process is a constitutively dynamic and systemic process. According to Valsiner’s model of the systemic duality of signs (Valsiner 2001; Valsiner and De Luca Picione 2017; Abbey and Valsiner 2007), each semiotic mediator consists of an opposition between the “manifest” sign (A) and its opposite counterpart (non-A). All signs and words are good examples; they work in dialogical opposition with their opposite background. The latter is necessary for the construction and recognition of the former. The background (non-A) is a poorly defined field where only the borders with the “manifest sign” can be determined (Valsiner and De Luca Picione 2017, p.99).

A further elaboration, coherent and in continuity with what we are expressing, of the semiotic dynamics of the signification process is proposed by Salvatore (2013, 2016a) on the reciprocity and mutuality of the sign and its emergency field (as context and framework of interpretation). Salvatore believes, in line with Peircean semiotics, that sensemaking process is regulated by the continuous and reciprocal comparison between “signs in presentia” (SIP) and “signs in absentia” (SIA); some combine to define and instantiate the others in a regenerative and endless cycle. Sergio Salvatore (2013) defines the dynamic, relational, and bivalent meaning:

The contextuality of signs is shown by the fact that the same sign may have many contents. A way of appreciating the polisemy of signs is by recognizing that meaning is inherently oppositional: to state the particular idea (a quality, an action, a condition…) involved is to state the negation of the opposing idea – the statement that “something is X” (“S is X”) means that “something is not something else that could have been instead of X” (“S is not ‘opX’”). Thus, for instance, “S is a girl” means “S is not a boy.” (Salvatore 2013, p. 25)

The bivalent aspect of the sign finds an interesting and useful conceptualization in the border model (Tateo 2018; Tateo and Marsico 2019; Español et al. 2018; Marsico and Tateo 2017; De Luca Picione 2020c; De Luca Picione 2017) as a semiotic device that allows sensemaking processes starting from its capacity for differentiation and connection:

Tracing a border is an action of differentiation based on certain criteria. Hence, within the new established entity (i.e. group, territory, category etc.) those units (i.e. individuals, things, dimensions etc.) that meet the selected criteria will be included and acquire a special value, while the others that do not have those characteristics will be excluded. As a result, once a boundary is traced, it operates to strengthen this distinction, reducing the internal differences and making possible the perception, construction or even the invention of a homogeneous unit. (Marsico and Tateo 2017, p. 5)

The idea that a meaning is expressed in relation to another that is opposed to it is also at the core of the systemic-relational model of psychotherapy of Valeria Ugazio (2013), which defines the notion of semantic polarities as antagonistic polarities of meaning through which each person, each family, and each group with its own story organizes the conversation. These dimensions of antagonistic meaning define what is relevant for each group, indicating that, with respect to the incessant and multiform flow of experience, through a dialectical process, they orient to construct an episode, namely, the minimum unit in which the discourse is articulated (Ugazio 2013). The semantic polarities therefore orient how the communicative exchange will be constructed and on what the narration will be centered. They represent dual category of reading of one’s own and others’ behaviors and, as such, guide both action and dialog.

Methodology of Research and Development of the Narrative Device “the upside down world”

The ideas and principles we have just explained—namely, at the basis of every sensemaking process of one’s own experience, there is a polarization of meanings—constitute the theoretical pivot of the development of the methodological framework for our research on the experience of the university inclusion and the narrative device we used. Believing that the semantic polarities constitute the beginning passage in the discretization of the meaning of one’s own experience and that each person uses these polarizations in an idiosyncratic and contingent way, we have indeed developed a narrative tool aimed to study this kind of process, in order to explore the experience of university inclusion. We have called this instrument “the upside down world,” explicitly referring to the carnival situation studied by Bachtin (2012), as a way of bringing together the opposites during the ritual carnival celebrations. During the carnival, one can indeed observe how each canonical and cultural scheme is reversed, leaving to coexist—in the popular and shared dramatization of the time of the ritual event—the polarities that govern the human experience as follows: birth/death, male/female, beauty/ugliness, old/young, high/low, poor/rich, etc. (Bachtin 2012; De Luca Picione and Valsiner 2017; De Luca Picione and Valsiner 2017).

In our research, the use of this device involves two phases as follows: a first narrative task consisting in the request to write one’s own experience of university inclusion and a second narrative task asks the narrator to transform and flip one’s own written narrative into its opposite (also this time in written form).

-

1.

Tell me about a university inclusion experience of yours.

-

2.

Turn your story into its opposite version. You are to flip your narrative into its opposite, without believing that there is an opposite objectively valid for everyone.

Indeed, the idea of using the notion of opposition has already been used in other test devices for psychosocial research, for example, the famous “semantic differential” of Osgood (Osgood et al. 1957). This tool is used to quantify the emotional and affective reactions that an object evokes on an individual level, and as such, it has been useful for detecting people’s attitudes. The construction of this instrument requires that no questions are asked to the interviewee, and for this purpose, a series of items are used: They consist of pairs of adjectives of opposite meaning (e.g., beautiful vs. ugly) among which we have a continuum with an ordinal rating scale.Footnote 4

The semantic differential therefore from our point of view recognizes the function and the valence of the semantic polarization in the sensemaking process and the way in which the interviewee places herself relating to some topics (chosen according to a criterion of relevance for the research and defined by the researcher). However, in order to obtain statistically measurable and computable results, he chooses to renounce the detection of those pairs of opposites that guide the construction of meaning in the subjective and idiosyncratic experience of each individual with respect to the context (which constitutes the specific relational ground of our interest).

Returning to our choice of using a double narrative tool, based on the qualitative detection of the sensemaking process, we believe that it is capable of catalyzing (Cabell & Valsiner 2014; De Luca Picione and Freda 2014) the fundamental process of opposition. It lets emerge those polarities of meaning that constitute the basic orientation in the narrative construction of one’s own experience in/between a cultural and intersubjective context.

In a first exploratory phase on the possibilities of using this tool, we asked 8 students to write their university experiences compared with the following five points separately as follows: (1) relationship with teachers, (2) relationship with colleagues, (3) motivation that led to the choice of the degree course, (4) job expectations after the conclusion of the studies, and (5) major obstacles encountered in the course of study.

As these stories were concluded, we asked to re-write them shifting upside down. The average time required for both tasks was between 30 and 45 min. At the end of the narrative session, we asked the interviewees to express their opinion on this tool, on the clarity of the delivery and on the difficulty in the execution. The feedback we received was positive; the tool seemed clear in its requests; no specific difficulties were found in recounting and in re-telling its own experiences; however, we found that asking too many questions took too long, interfering in some cases with diligence and enthusiasm in writing the last reversed narratives.

Ultimately, this experimentation phase showed that the tool allows multiple contents to emerge, not at all taken for granted, and above all in the inverted narratives it was possible to detect great creativity, innumerable ways of turning the contents upside down, leaving the narrator great freedom of expression in syntax and semantics. The reversal, as opposed narration, constituted for the researchers an interesting empirical support in phase of reading and in phase of analysis and discussion of the meaning of the narratives. We verified that the tool satisfactorily responded to our theoretical perspective and to that purposes for which it was implemented.

We have named the produced narratives within the first task as “positive,” while we have described the produced narratives within the second task as “negative.” This names, as it is easily understandable, have no value or prejudicial connotations but take its cue from the metaphor of photography and photographic film on which it is imprinted as negative.

Some short excerpts of narrations can be useful in order to clarify examples of double narrative process:

First excerpt:

-

a)

…I was lucky enough to relate to excellent teachers with whom I have been able to establish excellent relationships from a human point of view. They have positively developed my university education and are certainly a point of reference for future professional fulfillment.

➔ Upside-down narrative process➔

-

b)

The relationship with the professors has often been softer: too much distance and too little human contact, certainly because of the size of the university ... and the current situation, for the professors, of finding a relationship with different categories of students.

Second excerpt:

-

a)

It did not take me very long to get to know and bond with other peers, who immediately made themselves available to me.

➔ Upside-down narrative process➔

-

b)

It took me a long time to get to know and try to bond with other peers, who, having never seen me taking courses with them, did not give me the opportunity to integrate into their groups, leaving me isolated and without having someone with whom I could create a group of study..

Third excerpt:

-

a)

The teacher created a participatory atmosphere to make us work in a group made up of students with different aspects of personality.

➔ Upside-down narrative process➔

-

b)

The teachers were inclined to greet only the well-off students, and in forming the group work choices prevailed regarding the political class and belonging to the individual students.

Fourth excerpt:

-

a)

I felt inclusion as a common direction of adults towards a shared goal.

➔ Upside-down narrative process➔

-

b)

The general objective was to excel at all costs, even at the cost of trampling on everyone else.

Data Collection and Characteristics of Students Interviewed Narratively

We have collected 25 narratives in different study rooms of the biggest University of South Italy, asking the availability of students and guaranteeing total respect for their anonymity. The interviewed student population is quite heterogeneous, widely distributed among courses in humanistic and scientific studies (13 students of humanistic studies and 12 students of scientific studies). All the students collaborated with great alacrity and in an interested manner with respect to the double narrative task (it is worth to specify that the request to participate to the research was not advanced by professors or teachers but by mates). Each form of anonymity was respected, and participation was absolutely voluntary.

The average age of the sample was 23.5 years. Sixty percent of the respondents were male students. As for the university career, it emerges that 13 participants out of 25 are in compliance with the regular plan of examinations and 78% of them are satisfied with their average profit.

Results

In the first instance, we analyzed the narratives of the first task (so-called positive narratives) from a descriptive point of view in order to consider the vastness and heterogeneity of the stories, in terms of who, when, where, and how.

-

Protagonists. Who are the actants present in the narrative text?

-

Times. In what times and moments is the narrated experience placed?

-

Places. What are places involved in the narration?

-

Events. During which occasion is the inclusive experience placed?

In this way, we have been able to point out that—with relating to the experiences of university inclusion the actors involved, the temporal references, the spatial references, and the situations recounted—the narrative material presents a great variability and a profusion of subjective details that immediately let us glimpse how each student considers differently the notion of inclusion with reference to one’s own experience. We report the results of this descriptive analysis in the summary table (Table 1).

In a second phase of analysis, we analyzed the entire narrative corpus (obtained from the first and second task) in the following way: Every couple of narrations (the positive narrative with the negative counterpart) was analyzed by detecting the differences that emerged from their comparison. Once the semantic content of these differences was identified and collected, an abstraction and generalization was then carried out in order to allow a comparison between the different results. This process of analysis and judgment took place through the work of interpretation of three independent judges. Referring to the semiotic and dynamic perspective of the sensemaking process adopted in our research methodology, we have therefore not generalized the result starting from the referential content of the narrative, but we have abstracted the “question”Footnote 5 that emerged from the narrator’s own narrative when he transformed it into its opposite (Table 2). That makes it possible to achieve two different but interconnected aims as follows: (a) on the one hand, it allows to preserve the subjective specificity of each narrative process (the specific, idiosyncratic, and contextual polar dynamics underlying the narrative process of each narrator);( b) on the other hand, it allows to gain abstract results in order to be comparable between the different collected narrations (Freda 2008; Salvatore, 2016a; De Luca Picione 2015a) (Table 2).

Discussion

The results that emerged show a wide variety of themes involved in narrating the university inclusion experience, going through different areas of activity with other students, with teachers, with the provision of institutional services.

The descriptive analysis (Table 1) showed that in most of the narrations the actors involved are the professors, colleagues, and the group; in some narratives, however, more specific protagonists appear, such as the psychologists referred to in narration n.3, the rector and prefect of n.4 or the theater company of n.22. Finally, in some cases the inclusion experience refers more to a “family” dimension linked to girlfriends and cousins as occurs in the experience of narratives n. 3, 13, 15.

The experiences of inclusion embrace a series of circumstances and moments, some more recurrent such as passing an exam (narrations n. 3, 13, 20, 23, 25); others more punctual and specific linked to “complementary and extracurricular activities” (narration n.21) such as participation in international conferences, the Erasmus program of international mobility for students, events, or even the sharing of an unexpected and disturbing event such as of a terrifying lightning bolt during a lesson in the case of narration n.9.

Focusing on the places, as it is foreseeable, the privileged space referred to in the inclusive processes is the classrooms where the lessons are held. However, inclusive experiences also occur in other places, such as those of “power” as follows: the court (narration n.21), or the police headquarters and the rectorate (narration n.4). We find figurative examples of places, as in the case of the “muddy pond” to which the emphatic narrative of a medical student refers (narration n.15). There are also “border” places and their passage as in the case of a transfer from one university to another (narration n.2) or from one degree course to another (narration n.5), the road (narration n.4), the stage of a theater (narration n.22), and the place of a conference (narration n.6) or of an event that project to the future as in the case of an engineering student dealing with a jury of investors in the chamber of commerce (n.8) or even the case of an experience that cross a national border to reach another country (narration n.24).

The times showed in the narratives manifest a great variety. In some narrations, they are more precise and delimited and take on the coordinates of a specific temporal frame as follows: during the 7 months of Erasmus (n.24), in the first year (n.22), at the beginning of the second year of the triennial (n. 20), at the beginning of the master’s degree (n.19), and at the end of the study path (n.17). For other students, the temporal coordinates widen and become more extensional to include several years and/or the entire university path up to that time. The inclusive experience occurs for some “during all courses” in general, for others during the attendance of a single course taught by a specific professor.

The temporal dimension sometimes condenses with other dimensions such as with the space-place becoming an expression, a way of saying: “During university.” The time of inclusion narratives seems not only to be a chronological time, restricted or dilated, but it is also the time of relationship and context; paradoxically, time itself seems to lead us back to the person’s encounter with the culturally and emotionally connoted context.Footnote 6

The semiotic analysis of the double narration

From the comparison between the corresponding positive and negative narrations of each student, we extrapolated those polar couples through which the inclusion process is signified (Table 2). They have been abstracted (always reaching an agreement between three judges) in order to be compared with each other later. These polarizations can be considered as the basis of the signification process that the students presented in their narratives and provide us with relevant information on the most salient issues through which they are dealing with the topic of university inclusion.

Below we briefly list the salient nuclei of significance that emerged for each narration through polarization. In particular:

In the case of the narrator n.1, the polar couples contact/dispersion and idealism/realism connote the inclusion process as the possibility of establishing a direct, human, concrete relationship with the teachers, considered indispensable for future professional fulfillment.

For the narrator n.2, the polar pairs inside/outside, opening/closing, and immediacy/graduality suggest that the inclusion process has to do with the continuity of the study path, with its interruptions and changes, with the effort and the effort to build meaningful relationships over time, and with respect to new contexts.

For the narrator n.3, the polar pairs work/unproductivity, self-depreciation/re-evaluation, and punishment/concession organize the sensemaking of the inclusion process as linked to the significant meeting with the psychologists who made it possible to pass an exam through a process of self-appreciation.

For the narrator n.4, the polar pairs open/close, lawful/irregular, and imposition/voluntary participation are the basis of the inclusive experience read in terms of closing and opening the university institution and the definition of a “we” as opposed to the “you” beyond the barricade.

For the narrator n.5, the polar pairs opportunity/impossibility and difference/uniformity of mass connote the inclusive experience in terms of efforts to cancel social and economic differences from others.

For the narrator n.6, the polar couples designation/volunteering, elite/common people, and singular/ordinary are the basis of the story of an inclusion experience that is realized with the possibility of being chosen by the professor to participate in an exceptional international conference.

In the case of the narrator n.7, the polar pairs interest/boredom, specificity/genericity, and result/inconclusive inform that the inclusive experience is linked to the participation in the formative and profitable laboratory activities that when they fail they generate boredom and inconclusive state.

For the narrator n.8, the polar couples interaction/presentation, practice/theory, innovation/obsolete, offered opportunity/personal activation, and productivity/inconclusive constitute the meaning matrix of the inclusive experience as a practical and active opportunity to get involved.

For the narrator n.9, the ordinary/extraordinary, fright/joy, and interruption recovery polar couples organize the meaning of the inclusive experience as a context of strong emotional activation and sharing but which however is only temporary and not lasting compared with the training experience.

For the narrator n.10, the polar couples commitment/carefree and burden/digestion are the basis of the inclusive experience lived as a lightening of the workload through sharing and collaboration in the group of colleagues-friends.

For narrator n.11, interactivity with the professor makes the training experience more profitable as instanced by the polar couples who support this representation of inclusion as follows: interactivity/passivity and reciprocity/one-sidedness.

For narrator n.12, the inclusion experience is understood as working in a group coordinated by the professor making the study more stimulating and constructive. This meaning is based on the polar pairs of meaning interesting/difficult, engaging boring, and intentionality/occasionality.

For the narrator n.13, the polar couples difficulty/easy, contentment/dissatisfaction, and good/scarce organize the sensemaking of university inclusion by enhancing the presence and closeness of family and friends in difficult and uncertain times.

The narrator n.14 reports the inclusive experience in terms of possibilities and openness to diversity on the part of the teachers, rather than closing behind the discrimination and mistrust, based on the polar couples participation/discrimination, coexistence/the chosen, and exchange/closure.

For the narrator n.15, the experience of inclusion told how to be able to re-acquire self-confidence, to re-start to follow courses, to re-start “taking exams” is based on the polar pairs impasse/recovery, genuineness/rivalry, and luck/commitment.

For the narrator n.16, the polar couples are in the foreground being smart/being nerds, togetherness/not loving each other, and support/withdrawal. They give meaning to the inclusion experience told as the opportunity to meet people with whom to support each other in the study and team up together to achieve a common goal.

For the narrator n.17, the polar pairs assiduity/occasionality, obligation/volunteer, and stimulating/boring inform the inclusive experience takes the form of the integration of the academic manuals with the practical learning experienced together with the professors.

For the narrator n.18, the polar pairs activity/passivity, collaboration/taxation, and contribute/abandon found the story of the inclusive experience understood as not to suffer the choices of others but to be able to collaborate and contribute in the creation of new spaces and new ideas.

For the narrator n.19, we find the polar couples sharing/competition and regret/satisfaction to signify the inclusive experience as collaboration with colleagues for a common direction towards a shared goal.

For the narrator n.20, the polar couples get involved/retire, utility/disinterestedness, and trust/distrust inform the inclusive experience as an active productive and relaunch moment, as what can be the passing of an exam.

For narrator n.21, the polar pairs different/homogeneous, direct approach/theory, and uncertainty/evidence connote inclusive experience as an active and practical experiential process of learning and training.

For the narrator n.22, the polar couples move away/involvement, appreciate/hate, and coordinate/improvise organize the meanings of the experience inclusive of an extracurricular theatrical activity which, however, contributes to enhancing the training process.

For the narrator n.23, the polar couples distance/collaboration, equivalence/disparity, and facilitate/complicate inform the story of the experience of inclusion in the relationship with the teachers.

For the narrator n.24, the polar pairs formative/terrifying, descent/ascent, and achievement/missing organize the narrative of the inclusive experience as the achievement of the educational objectives within an experiential scenario characterized by the implicit possibility of difficulty and failure.

For the narrator n.25, the polar pairs chaos/organization, exception/majority, representatives/apparatus, and restricted-circle/majority-part are the basis of the story of the inclusive experience as the possibility of participation in training activities precluded to the majority of students without that this extension translates into disorder and confusion.

Lately, university inclusion emerges as a polysemic notion; each student points out a wide range of contents and idiosyncratic elements that personalize his or her inclusion experience. The sensemaking process contents of the inclusive experience are contingent, specific, and contextual elements that are organized starting from the contextual subject/alterity/ culture relationship (Freda & De Luca Picione 2014; De Luca Picione 2015a, 2015b; Salvatore and Valsiner 2010a).

The polarization of meanings has allowed us to grasp the more subjective dimensions of the narrative process. Meanwhile, by abstracting a series of general questions, we are interested in elaborating a further generalization step. We have identified two macro-areas that are somehow capable of representing the focal point of the inclusive process:

-

1)

The purpose. We have included here the polarities that refer to the educational and formative goal of the university experience.

-

2)

The positioning. By it we refer the polarities relevant to the relational movements and the mutual definitions of self-other.

Referring to the purpose, the recurrent polarities are those that refer to activity/passivity, stimulating/boring, and profitable/useless. In fact, it has emerged that university experience is considered inclusive when the theoretical dimension is supported by experiential and laboratory training courses, which respond to the objective of developing skills that can be spent in professional fields. The result of the recurrence of these polarities underlines the importance of the training process compared with its ability to support a professional development process. “The university becomes inclusive” in the students’ narratives when it creates bridges between present and future, when it connects the training experience with the working future and supports the student’s goal of becoming active and participant in his/her training path in the context and beyond a passive and fulfilling user.

Dealing with the positioning domain—which includes the polarities that describe or characterize the student and the other formative protagonists and the relationships between them—the most frequent semantic oppositions are as follows: opening/closing and distance/collaboration. They point out, as recurring and salient positioning ways, the importance of sharing and exchange both within the small group and the importance of direct contact and recognition by the institution. On the one hand, the training commitment becomes overwhelming if you do not have a group with which to share the work and its weight, with which to enjoy a few moments of light-heartedness. On the other hand, there was also a difficulty in defining oneself as individual subjects with respect to the institution, the mass, and the multitude perceived as distant, “closed,” and chaotic. The group identity and its internal relations act as a buffer which softens and negotiates distances.

It is worth to highlight that the domain of purpose and the domain of positioning are not strictly separated areas of inclusive experiences. There is a strong link between these two domains. They can consider as mutually feeding and strongly interrelated each other. The positioning between other social actors (professors, colleagues, mates, tutors, etc.) works as a process of construction of professional identity that orients and guides towards achievements of purposes. At same time, the chosen purposes (construction of skills and abilities) define specific ways to shape one’s one positioning.

Conclusions

By a narrative study and by the use of the double-narration tool that we have named “the upside down world,” we have considered how the inclusive experience is constructed through the personalization of the processes of sensemaking within a wider cultural and shared social context. The global analysis of the narratives shows that the inclusive experiences represent a positive and fertile development when the two macro-areas/trajectories of sensemaking (positioning and purpose) meet.

The work of reflection and analysis of the double narratives collected allows us to make a reading of the subjective experience of university inclusion.

The used semiotic narrative device allowed to observe, analyze, and discuss the process of sensemaking starting from the differential/oppositional relationships of meaning that we have triggered through the process of reversal of the narratives. In fact, the second narrative delivery, “Turn your story into its opposite version. You are invited to turn your narrative upside down in its opposite, without believing that each meaning corresponds to an objectively valid opposite”, has allowed a confrontation with the polysemy of meaning due to the infinite possibility of associating a single word and more precise and rich keys for the analysis of sensemaking processes.

The narrative path of research in different phases—first descriptive one and then reversal one—made use of a semiotic analysis process that investigated both the superficial/concrete level of the narrative experience and the more abstract and meaningful level (Greimas 1983; Thom 1988; Bundgaard & Stjernfelt, 2010; De Luca Picione and Freda 2016b), capturing the binary and oppositional processes of formation and construction of sense.

The experience of academic inclusion has been explored thanks to the work of coding, analysis, and discussion of semiotic polarities, that is, thanks to the identification and recognition of the semantic oppositions from which the sensemaking processes of the narrator students have been organized.

In summary, university inclusion appears narratively articulated on two broadly generalized domains of sense as follows: the relationship with others and the training path. On the one hand, the relationship with others refers to the collaboration, the possibility of interaction, and the connection with colleagues that can take place both in terms of “openness to the other” and of “sharing objectives for achieving a common goal.” On the other hand, the relationship dimension of inclusive experience also finds expression in terms of “group closure” where the processes of belonging and group identification can constitute the way of protection against dispersion, identity dilution, anonymity, and fragmentation towards the institution.

Another relevant aspect pertains to the integration of the oppositions between “theoretical approach” and “experiential approach” in the training path; the former refers to old habits, passivity, and something not innovative; the latter refers to modern interest, results, and discovery of the new but also to an “exceptionality,” which is unfortunately not always present in one’s study programs. It is also important to note that with respect to the issues of relationship with others and training, the figure of professors and teachers is a connection point felt to be very significant and decisive. Contact, reciprocity, and the relationship with professors are brought in the foreground inasmuch those are symbolized as “place” of learning (especially in the form of university research, laboratory experiences, connections between research and private entrepreneurship but also in humanistic and social studies, e.g., theater activities and international congresses for the matters of history and literature), indispensable for achieving the final goal of increasing one’s knowledge base and of knowing how to use them.

Furthermore, some semantic polarities have allowed to emerge trajectories of sensemaking that somehow seemed to be forever overcome since they appear as outdated in the Italian socioeconomic-cultural scenario. Those couples show issues about social class habitus, economic status, and conditions of discrimination relating to higher education and economic dimension of departure (e.g., participation/discrimination, social difference/mass, coexistence/the chosen, elite/common people).

From the students’ perspectives, a general idea of inclusion emerges as having the “possibility” of creating links between the educational and professional experience where “the University” (considered as a border of passage between olders and youngers and professors and students) becomes inclusive when the educational experience becomes a space-time context in which to grow personally, relationally, and professionally to “feel alive and active” in sharing a purpose together with one’s peers.

Notes

It is obvious that this is not considered sufficient for the development of a process of signification—whose symbolic complexity in human being goes far beyond the detection of binary pairs of signification. Such antagonistic couples are however constitutive of the sense of every experience, that is, they are the point of anchorage and starting point for the contextual construction of experience and its meaning.

Let us remember, for example, that Greimas conducted researches on some fundamental oppositions such as life/death, masculine/feminine, nature/culture, truth/lie, etc.

According to Greimas, the narrative process is constructed by means of conversion processes going from deep levels with more abstract, impersonal, and binary categories, to superficial levels characterized by more complex categories (enrichment of sense) and concrete categories (actorialization, spatialization, temporalization).

According to the originators of the semantic differential, Osgood, Suci, and Tannenbaum (1957), it would be possible to derive three distinct types of factors—deriving from a factorial analysis procedure. These factors are valuation, power, and activity.

Bakhtin elaborates the theory of the chronotope as a category concerning the interconnection of temporal and spatial relationships within a text: “... in this term the inseparability of space and time is expressed ... Time here becomes dense and compact and becomes artistically visible; the space intensifies and enters the movement of time of the plot, of the story. The connotations of time are manifested in space, to which time gives meaning and measure” (Bakhtin 2001, pp.231–232, our translation).

References

Abbey, E., & Valsiner, J. (2004, 2004). Emergence of meanings through ambivalence, Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: QualitativeSocial Research., 6(1), 23.

Assaf, D., Cohen, Y., Danesi, M., & Neuman, Y. (2015). Opposition theory and computational semiotics. Sign Systems Studies, 43(2/3), 159–172.

Bachtin, M. M. (2012). L'opera di Rabelais e la cultura popolare: riso, carnevale e festa nella tradizione medievale e rinascimentale. Torino: Einaudi.

Bakhtin, M. M. (2001). Le forme del tempo e del cronotopo nel romanzo. Saggi di poetica storica. In Estetica e romanzo. Torino: Einaudi.

Barrett, L. F. (2006). Solving the emotion paradox: Categorization and the experience of emotion. Personality and social psychology review, 10(1), 20–46.

Bateson, G. (1979). Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity (advances in systems theory, complexity, and the human sciences). Hampton Press.

Buhler, K. (1934). Spachteorie. Die Darstellungsfunktion der Sprache. Jena: Fischer.

Bundgaard, P. F., & Stjernfelt, F. (2010). René Thom's semiotics and its sources. In W. Wildgen, & B. Per Aage (Eds.), Semiosis and catastrophes. René Thom's semiotic heritage. Series: European Semiotics/Sémiotiques Européennes (Vol. 10). Bern, SW: Peter Lang.

Canevaro, A. (2005). Reducing handicap. Medicina nei Secoli, 18(2), 373–397.

Cole, M. (2004). Psicologia Culturale. Roma: Edizioni Carlo Amore.

De Luca Picione, R. (2014). The case of Neuman’s “computational cultural psychology”: an innovative theoretical proposal and welcomed toolbox advancements. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 10, 783–791.

De Luca Picione, R. (2015a). The idiographic approach in psychological research. The challenge of overcoming old distinctions without risking to homogenize. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 49, 360–370.

De Luca Picione, R. (2015b). La mente come forma. La mente come testo. Un’indagine semiotico-psicologica dei processi di significazione [the mind as form. The mind as text. A semiotic psychological research on sense-making processes]. Milan: Mimesis Edizioni.

De Luca Picione, R. (2017). La funzione dei confini e della liminalità nei processi narrativi. Una di-scussione semiotico-dinamica. International Journal of Psychoanalysis and Education, 9(2), 37–57.

De Luca Picione, R. (2019). La topologia e la psicoanalisi. Scritture (im-)possibili del buco e della soggettività. [Topology and Psychoanalysis. (Im-)possible writings of the hole and the subjectivity]. La Psicoanalisi. Studi internazionali del campo freudiano. 63/64, 205–231.

De Luca Picione, R. (2020a). The semiotic paradigm in psychology. A Mature Weltanschauung for the Definition of Semiotic Mind. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-020-09555-y.

De Luca Picione, R. (2020b). La proposta dell’Idiographic Science. Discussione degli assunti teorici, epistemologici e metodologici di un possibile approccio idiografico in psicologia. Ricerche di Psicologia, 44(2), 2020.

De Luca Picione, R. (2020c). Models of semiotic borders in psychology and their implications: From rigidity of separation to topological dynamics of connectivity. Theory and Psychology. in press

De Luca Picione, R., & Freda, M. F. (2012). Senso e significato (sense and meaning). Rivista di Psicologia Clinica, 2(2), 17–26.

De Luca Picione, R., & Freda, M. F. (2014). Catalysis and morphogenesis: The contextual semiotic configuration of form, function, and fields of experience. In, Cabell, K. R.& Valsiner, J.(Eds.), The catalyzing mind. Beyond models of causality. Annals of Theoretical Psychology (Vol. 11, pp. 29–43). New York, NY: Springer.

De Luca Picione, R., & Freda, M. F. (2016a). Borders and modal articulations: Semiotic constructs of sense-making processes enabling a fecund dialogue between cultural psychology and clinical psychology. Journal of Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 50, 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-015-9318-2.

De Luca Picione, R., & Freda, M. F. (2016b). The processes of meaning making, starting from the morphogenetic theories of Ren’e Thom. Culture & Psychology, 22, 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X15576171.

De Luca Picione, R., & Freda, M. F. (2016c). Possible use in psychology of threshold concept in order to study sensemaking processes. Culture & Psychology. Advance online publication. 1354067X16654858.

De Luca Picione, R., Dicè, F., & Freda, M. F. (2015). La comprensione della diagnosi di DSD da parte delle madri Uno studio sui processi di sensemaking attraverso una prospettiva semiotico-psicologica. Rivista di Psicologia della Salute, 2, 47–75.

De Luca Picione, R., Luisa Martino, M., & Freda, M. F. (2017). Understanding cancer patients’ narratives: Meaning-making process, temporality, and modal articulation. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 30(4), 339–359.

De Luca Picione, R., Martino, M. L., & Freda, M. F. (2018). Modal articulation: The psychological and semiotic functions of modalities in the sensemaking process. Theory & Psychology, 28(1), 84–103.

De Luca Picione, R., Martino, M. L., & Troisi, G. (2019). The semiotic construction of the sense of agency. The modal articulation in narrative processes. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 53(3), 431–449.

de Saussure, F. (1922). Corso di linguistica generale (p. 1967). Tr. it. Roma-Bari: Laterza.

Eidelsztein, A. (2015). Il grafo del desiderio. Formalizzazioni in psicoanalisi. Milano: Mimesis.

Español, A., Marsico, G., & Tateo, L. (2018). Maintaining borders: From border guards to diplomats. Human Affairs, 28(3), 443–460. https://doi.org/10.1515/humaff-2018-0036.

Fossa, P., Awad, N., Ramos, F., Molina, Y., De la Puerta, S., & Cornejo, C. (2018). Control del pensamiento, esfuerzo cognitivo y lenguaje fisionómico-organísmico: tres manifestaciones del lenguaje interior en la experiencia humana. Universitas Psychologica, 17(4).

Fossa, P., Gonzalez, N., & Di Montezemolo, F. C. (2019a). From inner speech to mind-wandering: Developing a comprehensive model of inner mental activity trajectories. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 53(2), 298–322.

Fossa, P., Pérez, R. M., & Marcotti, C. M. (2019b). The relationship between the inner speech and Emotions: Revisiting the Study of Passions in Psychology. Human Arenas. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-019-00079-5.

Freda, M. F. (2008). Narrazione e intervento in psicologia clinica. In Costruire, pensare e trasformare narrazioni. Napoli: Liguori.

Freda, M. F., Rainone, N., & Valerio, P. (2010). Inclusione e partecipazione attiva all’università’[‘Inclusion and active participation at university’]. Psicologia Scolastica, 9(1), 81–100.

Greimas, A. J. (1983). Structural semantics: An attempt at a method. University of Nebraska Press.

Heft, H. (2013). Environment, cognition, and culture: Reconsidering the cognitive map. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 33, 14–25.

Hoffmeyer, J. (1996). Signs of meaning in the universe. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Ianes, D. (2005). Special educational needs and inclusion: Assessing the real needs and enabling all resources. Trento: Erickson.

Linell, P. (2009). Rethinking language, mind, and world dialogically: Interactional and contextual theories of human sense-making. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

Lotman, J. (1985). La semiosfera. L’asimmetria e il dialogo nelle strutture pensanti. A cura di Salvestroni, S. Venezia: Marsilio.

Marková, I. (2003). Dialogicality and social representations - the dynamics of mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marsico, G., & Tateo, L. (2017). Borders, Tensegrity and development in dialogue. Integrative Psychological and Behavioural Sciences, 51(4), 536–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-017-9398-2.

Matte Blanco, I. (1975). The unconscious as infinite sets: An essay in bi-logic. London: Gerald Duckworth & Company.

Molina, M. E., & Del Río, M. T. (2009). Dynamics of psychotherapy processes. In J. En, P. Valsiner, M. Molenaar, & L. N. Chaudhary (Eds.), Handbook Dynamic Process Methodology in the Social and Developmental Science (pp. 455–475). New York: Springer-Verlag ISBN 978-0-387-95922-1.

Molina, M. E., Ben-Dov, P., Diez, M., Farrán, A., Rapaport, E., & Tomicic, A. (2013). Vínculo Terapéutico: Aproximación desde el diálogo y la co-construcción de significados. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 22(1), 15–21.

Molina, M. E., Del Rio, M. T., & Tapia, L. (2015). El diálogo en la psicoterapia: Protocolo para un análisis de micro-proceso. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 24(2), 121–132.

Neuman, Y. (2003a). Mobius and paradox: On the abstract structure of boundary events in semiotic systems. Semiotica, 147, 135–148.

Neuman, Y. (2003b). Processes and boundaries of the mind: extending the limit line. New York: Academic/Plenum Publishers, Springer.

Neuman, Y. (2014). Introduction to computational cultural psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Osgood, C. E., Suci, G., & Tannenbaum, P. (1957). The measurement of meaning. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Pérez, R. M., Fossa, P., & Barros, M. (2020). Emotions in the theory of cultural-historical subjectivity of González Rey. Hu Arenas. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-019-00092-8.

De Luca Picione, & Valsiner (2017). Psychological functions of semiotic borders in sense-making: Liminality of narrative processes. Europe’s Journal of Psychology.

Rainone, N., Freda, M. F., & Valerio, P. (2010). Inclusione e partecipazione attiva all’università. Psicologia Scolastica, 1(9), 81–98.

Salvatore, S. (2013). The reciprocal inherency of self and context. Notes for a semiotic model of the constitution of experience. Interacções. The semiotic construction of Self., 9(24), 20–50.

Salvatore, S. (2014). The mountain of cultural psychology and the mouse of empirical studies. Methodological considerations for birth control. Culture & Psychology, 20(4), 477–500.

Salvatore, S. (2016a). Psychology in black and white. The project of a theory-driven science. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

Salvatore, S. (2016b). The formalization of cultural psychology. Reasons and Functions. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 1–13.

Salvatore, S., & Freda, M. F. (2011). Affect, unconscious and sensemaking. a psychodynamic, semiotic and dialogic model. New Ideas in Psychology, 29, 119–135.

Salvatore, S., & Valsiner, J. (2010a). Between the general and the unique: overcoming the nomothetic versus idiographic opposition. Theory & Psychology, 20, 817–833.

Salvatore, S., & Valsiner, J. (2010b). Between the general and the unique overcoming the nomothetic versus idiographic opposition. Theory & Psychology, 20(6), 817–833.

Salvatore, S., & Zittoun, T. (2011). Cultural psychology and psychoanalysis. Pathway to synthesis. Greenwich: Information Age Publishing.

Sebeok, T. A. (1998). A sign is just a sign. La semiotica globale. Milano: Spirali.

Tateo, L. (2016). Toward a cogenetic cultural psychology. Culture & Psychology, 22(3), 433–447.

Tateo, L. (2018). Affective semiosis and affective logic. New Ideas in Psychology, 48, 1–1.

Tateo, L., & Marsico, G. (2019). Along the border: affective promotion or inhibition of conduct. Estudios de Psicología, 40(1), 245–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/02109395.2019.1569368.

Thom, R. (1988). Esquisse d’une Semìophysique. Paris: InterEditions.

Traini, S. (2013). Le basi della semiotica. Milano: Bompiani.

Ugazio, V. (2013). Semantic polarities and psychopathologies in the family: permitted and forbidden stories. London: Routledge.

Valerio, P., Striano, M., & Oliverio, S. (2013). Nessuno escluso. Formazione, inclusione sociale, cittadinanza attiva. Napoli: Liguori.

Valsiner, J. (2001). Process structure of semiotic mediation in human development. Human Development, 44(2-3), 84-97.

Valsiner, J. (2007). Culture in minds and societies: Foundations of cultural psychology. New Delhi: Sage.

Valsiner, J. (2014). An invitation to cultural psychology. London: Sage.

Valsiner, J., & De Luca Picione, R. (2017). La regolazione dinamica dei processi affettivi attraverso la mediazione semiotica. Rivista Internazionale di Filosofia e Psicologia., 8(1), 80–109. https://doi.org/10.4453/rifp.2017.0006.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cole, M. John-Steiner, V., Scribner, S. & Souberman, E. (Eds.). Cambridge: Harvard University press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Luca Picione, R., Testa, A. & Freda, M.F. The Sensemaking Process of Academic Inclusion Experience: A Semiotic Research Based upon the Innovative Narrative Methodology of “upside-down-world”. Hu Arenas 5, 122–142 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-020-00128-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-020-00128-4