Key summary points

Are there differences in health, functional, nutritional and psychological status among residents with cognitive impairment (CI) depending on where they stay, in nursing homes (NH) or residential homes (RH), and depending the level of CI?

AbstractSection FindingsThe NH and RH residents with CI differed in functional, nutritional status and some psychotic symptoms, but not in presence of chronic diseases, inappropriate behaviors and aggression. The level of CI was significantly associated with decline of physical, psychological functioning and nutritional status, but had no impact on placement in NH or RH.

AbstractSection MessageThe assessment of CI along with activities of daily living is an important part of a resident’s examination, to assure placement to appropriate LTC institution and adequate care delivery.

Abstract

Purpose

To find if there are differences in health, functional, nutritional and psychological status among residents with cognitive impairment (CI) depending on where they stay, in nursing homes (NH) or residential homes (RH), and depending on the level of CI. To find factors increasing the probability that the resident with CI stays in the NH compared to RH.

Design

A cross-sectional survey of a country-representative sample of 23 LTCIs randomly selected from all six regions in Poland was conducted in 2015–2016. We included 455 residents with CI: 214 recruited from 11 NHs and 241 from 12 RHs. Data were collected using the InterRAI-LTCF tool. The descriptive analysis and logistic regression models were used.

Results

The NH residents more frequently had worse functional and nutritional status, and psychotic symptoms than RH ones, while they did not differ significantly in health status, frequency of behavioral problems and aggression. More advanced CI was associated with higher presence of functional disability (ADL, bowel and bladder incontinence), nutritional decline (BMI, swallowing problems, aspiration, pressure ulcers) and psychological problems (aggression, resistance to care, agitation, hallucinations and delusions). Nevertheless, the level of CI severity did not increase the chance to stay in NH compared to RH, but ADL dependency did (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.31–1.76).

Conclusion

The level of CI is significantly associated with physical, psychological and nutritional functioning of residents and thus may have an impact on care needs. Therefore, it is very important to use CI assessments while referring to NH or RH, to ensure that patients with CI are placed in an appropriate facility, where they may receive optimal care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although dementia and other cognitive impairments (CI) have become one of the biggest challenges for long-term care institutions (LTCIs), large-scale nationwide comparative studies of older adults with CI in institutional care hardly exist in Poland. Starting from the year 1989, market-based mechanism had been incorporated into the health-care sector in the country. The subsequent reforms of health and social care sector led to a reduction in the number of hospital beds and shortening of the average length of stay in a hospital from 12.5 days in 1990 to 5.3 days in 2016. Due to economic reasons, most chronically ill and disabled patients tended to be discharged home early to wait for months or years for admission to a residential home (RH) organized in the social care sector. To fill that gap and take care of these patients, a new type of LTCI—the nursing home (NH), had been established in the framework of the health-care sector.

Referring to the classification proposed by experts’ panel on 2015 [1], the NH in Poland reminds the most a skilled nursing facility, which is managed by a physician as a medical director and provides 24-h a day and 7 days a week nursing and medical care by on-site employed physicians and nurses (specialists in long-term care nursing). The NH employs also formal care assistants who carry out daily personal care and professionals performing different therapies for at least 5 days a week (e.g., physiotherapy—PT, occupational therapy—OT) and consultancy (e.g., psychologist, dietitian) with the main aim of avoiding hospitalization of community dwelling patients or facilitating early hospital discharge. This is a description of the most common type of NH in Poland called a Care and Treatment Institution (in Polish ZOL—Zakład Opiekuńczo-Leczniczy). There is also a little different one called a Nursing and Care Institution (in Polish ZPO—Zakład Pielęgnacyjno-Opiekuńczy), where a registered nurse (with a Master of Nursing diploma) may manage the institution as a director, and physicians are not obliged to be on 24/7 duty, but employed on-site on part-time or full-time job.

The RH (in Polish DPS—Dom Pomocy Społecznej) in Poland is a residential facility which exactly matches the goals stated by the mentioned experts’ panel [1], as the facility is “primarily intended for those who require assistance with ADLs and IADLs, and/or for those who have behavioral problems due to dementia.” The RH focuses on “providing a supportive and a safe, homey environment while assisting the resident in maintaining functional status for as long as possible.” The residents move from their flats to RH and stay there forever. Therefore, they (like other community dwelling people) remain under the care of a family doctor (an off-site physician), visiting them in the RH or admitting in their outpatient clinic. The RH assures a round-the-clock personal care performed by the on-site employed care assistants who are trained in ADL and IADL assistance, but not educated and not allowed to perform most nursing procedures (i.e., drug administration or giving injections, wound care). Therefore, nurses employed on-site or off-site the RH (the last option recently becomes more frequent) provide nursing care. Furthermore, RH provides physiotherapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT) and consultancy of other professionals (ex. psychologist, dietician, social worker), who are employed on-site in the facility.

Yearly, over 100 thousand older persons reside in LTCIs in Poland. However, data on their characteristics and condition provided by the Central Statistical Office’s statistics is limited to age, sex and the number of bedridden residents [2, 3]. The results of our previous studies indicated that health and functional status of NH and RH residents differ [4]. However, our understanding of such problems among residents with CI is scant.

The aim of this paper is to compare the health, functional, nutritional and psychological status of the residents with CI in two cross-sectional samples from NHs and RHs in Poland. We would like to learn if and how the characteristics of cognitively impaired residents differ between NH and RH. Does whether they differ depends on the level of CI? What are the main factors increasing their chances to be treated in an NH compared to RH?

Methods

A cross-sectional survey of a country-representative sample of 23 facilities, randomly selected from all six regions in Poland, was conducted in the years 2015–2016. The facilities were randomized by geographical region, bed capacity, ownership status and type: NH or RH. The detailed description of the facilities in terms of staff resources, ownership, organization, and their sampling and recruitment process has been presented elsewhere [5]. NHs are targeted at highly disabled residents with a Barthel Index (BI) score less than 40 points (which is the basic admission criterion), while RHs provide care to less ADL-dependent people.

Study design

The study received approval from the relevant ethical committee. It consisted of two stages. First, we identified the residents with CI (n = 1035)—among all 1587 residents recruited from 23 LTCIs—based on Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) score with a cutoff of ≥ 2 points. The CPS is a five-item observational scale embedded in InterRAI Long-Term Care Facilities Assessment System questionnaire (InterRAI-LTCF). It demonstrated high agreement with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [6] and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [7], and similar performance to detect CI in LTC residents. The results of the first stage have been described elsewhere [5]. Afterward, 20 residents with CI were randomly selected from each facility (Fig. 1). Finally, we collected data from 455 residents using the InterRAI-LTCF questionnaire, which is a validated and widely used tool enabling comprehensive geriatric assessment of people receiving LTC services [8, 9]. The assessments were carried out by regular staff at each institution—a nurse or a psychologist—after standardized training performed by one researcher.

Flowchart of the obtained sample of LTCI residents with cognitive impairment in 23 facilities (stage 1 and stage 2). The figure shows the recruitment procedure for the study and the individual stages of patient selection for study 1 and study 2, as well as the cases excluded from the analysis. Abbreviation CPS means Cognitive Performance Scale, a tool used to assess the level of cognitive function among LTCI residents, and InterRAI-LTCF means InterRAI Long-Term Care Facilities Assessment System questionnaire, a tool enabling comprehensive geriatric assessment of people receiving LTC services

Variables and outcomes

We applied a seven-point Activities of Daily Living Hierarchy scale (ADLh) measuring functional performance based on four items: personal hygiene, locomotion, toilet use, and eating. It categorizes residents as independent (ADLh = 0–1); moderately dependent (ADLh = 2–3), and severely dependent (ADLh = 4–6) [10]. The level of CI was based on the CPS scale, where 2 is mild CI, 3–4 is moderate CI, and 5–6 is severe CI [6]. The four‐item Aggressive Behavior Scale (ABS) scale measures verbal and physical abuse, socially inappropriate behavior, and resistance to care, where a higher score indicates a greater frequency of aggressive behavior (range from 0 to 12) [11]. The Pressure Ulcer Risk Scale (PURS) ranges from 0 to 8 points, where higher scores indicate a higher relative risk for developing a new pressure ulcer (PU) [12].

All analyses in this paper were conducted with focus on comparing the NHs and RHs residents, and to compare residents with different levels of CI (mild, moderate, and severe). All the data were collected based on 3-day observation with the exception of the data on infectious diseases and weight loss, which were applied for the last 30 days prior to the day of the assessment and chronic diseases currently being treated.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were applied to compare NH and RH populations and the residents with different levels of CI. We applied a multivariate logistic regression model to find factors increasing the chance to be a resident of NH compared to RH. We included only the variables, which were significant in firstly performed univariate analysis or might be potential reasons for a stay in the NH. An interaction of each of them with the dependent variable was tested. Due to the collinearity with the ADLh variable, the PURS, bladder incontinence, bowel incontinence, and indwelling catheter variables were excluded. In the final multivariable regression model, all variables were retained for which the main effect was significant at a level of less than 0.3 or their presence in the model was otherwise justified (i.e., level of CI, gender, age). Differences were considered statistically significant if the p value was less than 0.05. All the analyses were performed with SPSS 25.

Results

Prevalence of infections, chronic diseases, and symptoms

The study group included 455 LTCI residents with a median age of 81 years; 70.1% were females. NH residents were more dependent in performing ADL and more cognitively impaired compared to RH residents. Functional disability and being underweight appeared more frequently in the group of people with severe CI (Table 1).

Residents from NHs compared to RHs more frequently had respiratory tract infections and history of stroke. On the contrary, cancer and psychiatric diseases were significantly more common in RHs. They did not differ in prevalence of most chronic diseases. As such, no differences in the prevalence of the analyzed diseases depending on the level of CI, except for ischemic heart diseases and infections, were found (Table 2).

NH patients more frequently had hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders as well as swallowing problems, aspiration, dehydration, and required tube feeding compared to RH residents. Most of them had some walking limitations. In our study, the prevalence of the analyzed symptoms of diseases (except dyspnea) was higher among the residents with moderate or severe CI (Table 2).

Prevalence of behavioral problems

Behavioral problems were present in 1/6 to 1/3 of LTC residents with CI. With one exception (verbal abuse), their prevalence was about two or three times higher in residents with moderate or severe CI, compared to mild CI. However, we did not find differences between NH and RH residents, with the exception of resistance to care (Table 2).

Activities of daily living

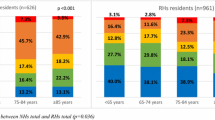

Severe functional disability in performing activities of daily living measured with an ADLh score of 4 or higher appeared more frequently among NH residents compared to RH residents and was associated with severity of CI (Table 1). Moreover, we found that functional disability was significantly higher in NH residents than in RH residents in each CI group. The mean ADLh scores differed between NH and RH the most in residents with mild CI. The highest scores were for residents with severe CI (Fig. 2, Online Resources 1&2).

Prevalence of the selected geriatric problems (body mass index, ADL dependency, risk of developing a new pressure ulcer, aggressive behaviors) among residents with cognitive impairment—a comparison between NHs and RHs and a comparison between levels of cognitive impairment in a random sample of 455 residents from 23 LTC settings in Poland. Mean and 95% CI (confidence interval) are presented. Exact mean scores, standard deviation (SD), and 95% confidence interval are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. To compare the two groups of NH and RH populations, we applied the Mann–Whitney U test, while differences between three levels of CI were calculated using Kruskal–Wallis H test

Bowel and bladder incontinence

The prevalence of total bowel and bladder incontinence was significantly higher among residents in NHs than in RHs, and among residents with severe CI compared to mild and moderate CI. In our study, in the group with mild and moderate CI both types of incontinence were significantly less frequent in RH patients. No significant differences in prevalence of bowel incontinence were found for NH and RH residents with severe CI (Fig. 3).

Differences in prevalence of bladder and bowel incontinence—a comparison between NHs and RHs depends on the level of CI and a comparison between levels of cognitive impairment in a random sample of 455 residents from 23 LTC settings in Poland. The p value (*) shows the difference between NS and RH residents with the same level of CI, while the p value (†) shows the difference between LTC residents depending on the level of CI. Bladder incontinence refers to lack of control of bladder function (including any level of dribbling or wetting of urine), with bladder programs of appliances. Full control—the patient does not use any type of catheter or urinary collection device. Partial incontinence—includes infrequent, occasional, or frequent episodes of incontinence. Total incontinence—no control of bladder, multiple daily episodes all or almost all of the time or control with the use of any type of catheter or urinary collection device. Bowel incontinence refers to lack of control of bowel function (including any leaking of stool or fecal material), with bowel programs or appliances. Full control—the patient does not use any type of ostomy device. Partial incontinence—includes infrequent, occasional, or frequent episodes of incontinence. Total incontinence—no control of bowel, multiple daily episodes all or almost all of the time, or control with ostomy device. Missing values: bladder incontinence: 1, bowel incontinence: 2

Aggressive behaviors

Aggressive behaviors (AB) concerned almost every second LTC resident with an ABS score of 1 or higher, with 12.7% scoring in the more severe range (5 or higher). No significant differences were found between NH and RH residents, albeit AB increased with severity of CI (Table 2). The mean ABS scores were significantly higher in residents with more advanced CI. However, comparative analysis of NH and RH residents in particular groups of CI (mild, moderate, severe) revealed no significant differences (Fig. 2, Online Resources 1 and 2).

BMI and weight loss

Weight loss of 5% or more in the last 30 days appeared significantly more often among NH residents in comparison to RH ones. This problem affected more often the residents with severe CI compared to ones with mild CI (Table 2). The mean BMI scores in NH residents were lower than in RH residents within each level of CI, although not significantly (Fig. 2). However, we noticed significantly lower BMI scores among residents with severe CI in both types of LTCIs. For the mean BMI scores, see Online Resources 1 and 2.

Risk of pressure ulcers

A higher risk of developing a new PU measured with a PURS score of 3 or higher appeared significantly more frequently among NH residents compared to RH ones, and in residents with severe CI compared to individuals with mild CI. Furthermore, this risk was significantly higher in NHs compared to RHs in each CI group of residents (Fig. 2, Online Resources 1 and 2).

Resident characteristics which determine where they stay in NH or RH

Univariate logistic regression models showed that worse functional status, older age, history of stroke, hallucinations or delusions, and sleep disorders were more probable in NH residents. Respiratory infection or problems with swallowing were twice more likely among them, while an indwelling catheter was six times more likely. A higher risk of PU, lower BMI, and advanced bladder or bowel incontinence were also more probable in NH residents.

The multivariate regression model showed that the level of CI severity did not increase the chance to stay in NH, independently of other factors. On the contrary, ADL dependency increased that chance by 52% with ADL worsening by each one point. The NH residents were more likely to have lower BMI score (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.92–0.99), history of stroke (OR 1.70, 95% CI 1.03–2.79), respiratory infection other than pneumonia (OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.26–3.82), hallucinations, and delusions (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.01–2.82) (Online Resource 3). The other variables from Table 2 were tested but were not significant.

Discussion

Our previous study showed that there was a high prevalence of CI in LTCIs in Poland, particularly among NH residents (74.5%) [5]. In another study, we found that health and functional status of NH and RH residents differ in terms of the prevalence of chronic somatic diseases and geriatric syndromes [4]. In this paper, we studied if residents with CI differ depending on where they stay; in an NH or RH. Secondly, we assessed their health, functional, psychological, and nutritional status based on the level of CI. Finally, we searched for factors which increase a resident’s chance to stay in NH compared to RH.

Functional status

We found significant differences in functional status of LTC residents in terms of the facility type and severity of CI. Both types of incontinence were highly prevalent among people with CI (affecting more than 80% of them), which is in concordance with other studies reporting the prevalence of urinary incontinence among institutionalized people as 54.4–82.9% [8, 13,14,15] and fecal incontinence as 34.8–58.9% [16, 17]. There is evidence that a higher risk of both types of incontinence is associated with cognitive decline, ADL limitations, and mobility impairment [16,17,18,19]. Our study indicated that NH residents with CI had worse functional status than RH residents, and it was strongly associated with the level of CI in both types of institutions. In the literature, there are numerous evidences that cognitive decline affects functional status among institutionalized older adults [20, 21]. However, the multivariate analysis in our study showed that the ADL-dependency level (not CI) was an independent factor that increased a resident’s chance to stay in an NH (which provides more nursing and medical care services including 24/7 access to a physician). It is contrary to other studies, where CI was positively associated with admission to NH [22,23,24,25]. The differences between NH and RH residents, we found, may basically result from admission criteria to NH, which are based in Poland on a Barthel Index score of less than 40. The internal organization of LTCI differs between countries, and it may implicate differences reported in other papers.

Health status

Although we might expect worse health status of the residents of NH, we did not find much difference with RH residents, with the exception of acute upper respiratory tract infection (probably due to disability) and a history of stroke (the reason of admission to NH with the aim of rehabilitation), which were more frequent in NH residents. The prevalence of other selected infectious and chronic diseases were reported on a similar level in both study groups (NHs and RHs), but cancer and psychiatric diseases were less frequent in NHs due to admission criteria excluding these diagnosis. Another important finding is that severe CI both in NH and RH is more often accompanied with urinary tract and respiratory infections, and ischemic heart disease, but not other chronic diseases.

Nutritional status

We found significant differences in nutritional status, which was worse in NH residents and was associated with the level of CI. The residents with severe CI both in NH and RH had lower BMI, greater weight loss, and a higher risk of developing a new PU compared to individuals with moderate or mild CI. These are indicators of the general biological condition and have prognostic value [26, 27]. It has been proven that lower BMI is related to higher mortality, while weight loss may be a part of the pre-terminal stage of a resident’s life [28,29,30]. The impaired capacity to swallow in older adults may have long-term consequences with severe health implications such as malnutrition, dehydration, and aspiration pneumonia [31]. Swallowing problems, aspiration, and dehydration were more common among NH residents and more frequent in the residents with severe CI, yet our study provided lower rates of swallowing problems than those of other authors [31, 32]. In general, the PU rates in our study were consistent with rates previously reported in the literature which varied between 2.2% and 23.9% in NHs [33]. Although the overall prevalence of PU was relatively low in both study groups (5.1% in RHs and of 9.7% in NHs), it was higher in residents with more severe CI (14.7%). Furthermore, a high risk of developing a new PU was reported more often in NH residents and it also was associated with the level of cognitive dysfunction.

Psychological status

Behavioral disorders and aggression are quite common in patients with dementia, significantly increasing the rates of nursing home placement [34]. In our study, we found that some psychotic symptoms (hallucinations, delusions) and sleep disorders were more frequent in NH residents compared with RH residents, but the prevalence of aggression and agitation did not differ significantly between institutions, which may cause the same burden on staff despite different human resources. Moreover, the severity level of CI was associated with higher prevalence of agitation, and some behavioral problems like wandering, physical abuse, socially inappropriate behaviors, and resistance to care that are part of aggressive behaviors. These findings are in concordance with other studies reporting association between cognitive decline and aggressiveness [35] and behavioral symptoms [36]. Similarly, the frequency of mental illness (such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder) in our study were consistent with rates previously reported in the literature [37]. Low rates are due to the admission criteria and indication for placement in other mental health facilities.

The role of cognitive function assessment in referring to institutional care

Our paper showed that admission criteria may have significant impact on characteristics of residents residing in the LTCI. In the world, there are many good examples of admission algorithms to LTC facilities. Most of them include ADL and CI as two key criteria differentiating patients and classifying to deferent levels of care. For example, MI Choice Screening algorithm applied in Michigan State in the USA points out 13 characteristics as important factors to make decision on patient eligibility to NH [38]. In Canada, the Method for Assigning Priority Levels (MAPLE) is used to appropriately allocate home care resources and placement in LTCI based on assessment of ADL, CI, behavior problems, skin ulcers, and problems with decision making and medication management [39]. Unfortunately in Poland, the main criteria for admission to stay in NHs are just a Barthel Index score less than 40 (in scale 0–100). Neither stage of dementia nor level of CI is considered as a formal eligibility criterion, which was also confirmed in the multivariate analysis. As a result of such a situation, patients with similar severity of CI may be admitted both to NH or RH, where they receive a different range of services. The insufficient number of geriatricians may be an obstacle for routine geriatric comprehensive assessment before referring to NH, since in Poland we have the lowest rate of geriatricians in the EU (less than 0.5 per 1000 people at age of 60 years and older; 447 geriatricians in 2019). As a consequence, not all older people admitted to NH or RH had underwent a diagnostic procedure toward dementia. However, implementing a short screening at referral to LTCI might be helpful to detect CI. There is a bunch of scales among which Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [40], Clock Drawing Test [41], the Montreal Cognitive Assessment [42], and the recently developed Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination—ACE-III [43] are the most commonly used. Yet, they require staff with experience in performing these. Therefore in case the geriatrician, psychiatrist, or neurologist is not accessible, the simple short test (for example AMTS—The Abbreviated Mental Test Score [44], SPMSQ—Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire [45], M-ACE—Mini-Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination [46, 47], or CPS) might be useful for screening residents at the time of making referral to the LTCI. A more in-depth evaluation might be performed by a psychologist in the facility after admission to elaborate a care and treatment plan.

Strengths and limitations

This is an epidemiological cross-sectional study, which by design has some limitations. However, it is the first research in Poland with a large sample size of residents with CI randomly selected from two types of LTCIs representative for the entire country. We provided a detailed description based on a comprehensive assessment of health, functional, nutritional, and psychological status of the residents depending on the level of their CI. Moreover, we revealed differences between NH and RH residents with the same level of cognitive disorders. Thus, our findings add to the better understanding of the complexity of needs of residents with the same severity of CI, but residing in different types of facilities.

Conclusions

We found that residents with CI in NHs and in RHs differed in terms of functional and nutritional status, stroke history, the presence of some psychotic symptoms, and respiratory infections other than pneumonia, but not in terms of most chronic diseases, other infections (including pneumonia), and aggressive behaviors. Moreover, the level of CI was significantly associated with physical (functional decline in ADL, bladder and bowel incontinence), psychological functioning (behavior problems and psychotic symptoms), and nutritional status (malnutrition increasing risk of PU) of the residents. Nevertheless, it had no independent influence on where—in what type of facility—the residents were placed, which was probably due to simplified admission criteria narrowed to the value of Barthel Index only. Our study showed that it is very important to use basic admission criteria to LTCI based on both ADL and CI assessments. Otherwise, patients with CI are at risk of being placed in an inappropriate facility, where they may receive sub-optimal care.

Abbreviations

- AB:

-

Aggressive behaviors

- ABS:

-

Aggressive Behavior Scale

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- ADLh:

-

Activities of Daily Living Hierarchy scale

- BI:

-

Barthel Index

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Cognitive impairment

- CPS:

-

Cognitive Performance Scale

- InterRAI-LTCF:

-

The InterRAI Long-Term Care Facilities Assessment System questionnaire

- LTC:

-

Long-term care

- LTCI:

-

Long-term care institution

- NH:

-

Nursing home

- PU:

-

Pressure ulcer

- PURS:

-

Pressure Ulcer Risk Scale

- RH:

-

Residential home

References

Sanford AM, Orrell M, Tolson D, Abbatecola AM, Arai H, Bauer JM et al (2015) An international definition for “nursing home”. J Am Med Dir Assoc 16:181–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.12.013

Social assistance, child and family services in 2017. Statistics Poland, Social Surveys Department. Warsaw: 2018

Health and Health Care in 2017. Statistics Poland, Social Surveys Department, Statistical Office in Kraków. Warsaw: 2019

Kijowska V, Wilga M, Szczerbińska K (2016) The prevalence of chronic diseases and geriatric problems—a comparison of nursing home residents in the skilled and nonskilled long-term care facilities in Poland. Pol Merkur Lek (Pol Med J) XLI/242:84–89

Kijowska V, Szczerbińska K (2018) Prevalence of cognitive impairment among long-term care residents: a comparison between nursing homes and residential homes in Poland. Eur Geriatr Med 9:467–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0062-2

Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, Hawes C, Phillips C, Mor V et al (1994) MDS cognitive performance scale. J Gerontol 49:M174–M182

Jones K, Perlman CM, Hirdes JP, Scott T (2010) Screening cognitive performance with the resident assessment instrument for mental health cognitive performance scale. Can J Psychiatry 55:736–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371005501108

Onder G, Carpenter I, Finne-Soveri H, Gindin J, Frijters D, Henrard JC et al (2012) Assessment of nursing home residents in Europe: the Services and Health for Elderly in Long TERm care (SHELTER) study. BMC Health Serv Res 12:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-5

Hirdes JP, Ljunggren G, Morris JN, Frijters DH, Finne Soveri H, Gray L et al (2008) Reliability of the interRAI suite of assessment instruments: a 12-country study of an integrated health information system. BMC Health Serv Res 8:277. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-277

Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA (1999) Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 54:M546–M553. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/54.11.m546

Perlman CM, Hirdes JP (2008) The aggressive behavior scale: a new scale to measure aggression based on the minimum data set. J Am Geriatr Soc 56:2298–2303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02048.x

Poss J, Murphy KM, Woodbury MG, Orsted H, Stevenson K, Williams G et al (2010) Development of the interRAI Pressure Ulcer Risk Scale (PURS) for use in long-term care and home care settings. BMC Geriatr 10:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-10-67

Rose A, Thimme A, Halfar C, Nehen HG, Rübben H (2013) Severity of urinary incontinence of nursing home residents correlates with malnutrition, dementia and loss of mobility. Urol Int 91:165–169. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348344

Aggazzotti G, Pesce F, Grassi D, Fantuzzi G, Righi E, De Vita D et al (2000) Prevalence of urinary incontinence among institutionalized patients: a cross-sectional epidemiologic study in a midsized city in northern Italy. Urology 56:245–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00643-9

Durrant J, Snape J (2003) Urinary incontinence in nursing homes for older people. Age Ageing 32:12–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/32.1.12

Hellström L, Ekelund P, Milsom I, Skoog I (1994) The influence of dementia on the prevalence of urinary and faecal incontinence in 85-year-old men and women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 19:11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4943(94)90021-3

Jerez-Roig J, Souza DLB, Amaral FLJS, Lima KC (2015) Prevalence of fecal incontinence (FI) and associated factors in institutionalized older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 60:425–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2015.02.003

Jerez-Roig J, Santos MM, Souza DLB, Amaral FLJS, Lima KC (2016) Prevalence of urinary incontinence and associated factors in nursing home residents. Neurourol Urodyn 35:102–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.22675

Saga S, Vinsnes AG, Mørkved S, Norton C, Seim A (2013) Prevalence and correlates of fecal incontinence among nursing home residents: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 13:87. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-13-87

Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Lipson S, Werner P (1999) Predictors of mortality in nursing home residents. J Clin Epidemiol 52:273–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00156-5

Jerez-Roig J, de Brito Macedo Ferreira LM, Torres de Araújo JRT, Costa Lima K (2017) Functional decline in nursing home residents: a prognostic study. PLoS One 12:e0177353. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177353

Belgrave LL, Bradsher JE (1994) Health as a factor in institutionalization. Res Aging 16:115–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027594162001

Chodosh J, Seeman TE, Keeler E, Sewall A, Hirsch SH, Guralnik JM et al (2004) Cognitive decline in high-functioning older persons is associated with an increased risk of hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc 52:1456–1462. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52407.x

Eaker ED, Vierkant RA, Mickel SF (2002) Predictors of nursing home admission and/or death in incident Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia cases compared to controls: a population-based study. J Clin Epidemiol 55:462–468

St John PD, Montgomery PR, Kristjansson B, McDowell I (2002) Cognitive scores, even within the normal range, predict death and institutionalization. Age Ageing 31:373–378. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/31.5.373

Murden RA, Ainslie NK (1994) Recent weight loss is related to short-term mortality in nursing homes. J Gen Intern Med 9:648–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02600311

Sullivan DH, Johnson LE, Bopp MM, Roberson PK (2004) Prognostic significance of monthly weight fluctuations among older nursing home residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59:M633–M639. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/59.6.m633

Veronese N, De Rui M, Toffanello ED, De Ronch I, Perissinotto E, Bolzetta F et al (2013) Body mass index as a predictor of all-cause mortality in nursing home residents during a 5-year follow-up. J Am Med Dir Assoc 14:53–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2012.09.014

Cereda E, Pedrolli C, Zagami A, Vanotti A, Piffer S, Opizzi A et al (2011) Body mass index and mortality in institutionalized elderly. J Am Med Dir Assoc 12:174–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2010.11.013

Vossius C, Selbæk G, Šaltytė Benth J, Bergh S (2018) Mortality in nursing home residents: a longitudinal study over three years. PLoS One 13:e0203480. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203480

Allepaerts S, Delcourt S, Petermans J (2008) Swallowing disorders in the elderly: an underestimated problem. Rev Med Liege 63:715–721

Humbert IA, Robbins J (2008) Dysphagia in the elderly. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 19:853–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2008.06.002

Lyder CH (2003) Pressure ulcer prevention and management. JAMA 289:223. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.2.223

Brodaty H, Draper B, Saab D, Low LF, Richards V, Paton H et al (2001) Psychosis, depression and behavioural disturbances in Sydney nursing home residents: prevalence and predictors. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 16:504–512

Margari F, Sicolo M, Spinelli L, Mastroianni F, Pastore A, Craig F et al (2012) Aggressive behavior, cognitive impairment, and depressive symptoms in elderly subjects. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 8:347–353. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S33745

Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Reed D (2014) Dementia prevalence and care in assisted living. Health Aff 33:658–666. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1255

Abrahamson K, Clark D, Perkins A, Arling G (2012) Does cognitive impairment influence quality of life among nursing home residents? Gerontologist 52:632–640. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr137

Fries BE, Shugarman LR, Morris JN, Simon SE, James M (2002) A screening system for Michigan’s home- and community-based long-term care programs. Gerontologist 42:462–474. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/42.4.462

Hirdes JP, Poss JW, Curtin-Telegdi N (2008) The Method for Assigning Priority Levels (MAPLe): a new decision-support system for allocating home care resources. BMC Med 6:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-6-9

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) Mini-mental state. J Psychiatr Res 12:189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

Pinto E, Peters R (2009) Literature review of the clock drawing test as a tool for cognitive screening. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 27:201–213. https://doi.org/10.1159/000203344

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bãdirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I et al (2005) The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 53:695–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

Mathuranath PS, Nestor PJ, Berrios GE, Rakowicz W, Hodges JR (2000) A brief cognitive test battery to differentiate Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 55:1613–1620. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000434309.85312.19

Hodkinson HM (1972) Evaluation of a mental test score for assessment of mental impairment in the elderly. Age Ageing 1:233–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/1.4.233

Pfeiffer E (1975) A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 23:433–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x

Hsieh S, McGrory S, Leslie F, Dawson K, Ahmed S, Butler CR et al (2015) The Mini-Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination: a new assessment tool for dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 39:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1159/000366040

Hodges JR, Larner AJ (2017) Addenbrooke’s cognitive examinations: ACE, ACE-R, ACE-III, ACEapp, and M-ACE. In: Larner A (ed) Cognition screening instruments a practical approach, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin, pp 109–137

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the managers of long-term care facilities in Poland who allowed the study to be conducted in their centers, and to the facilities’ nursing staff for participating in collecting the data.

Funding

This work was supported by the Jagiellonian University Medical College (Grant No. K/DSC/003080).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: VK and KS. Acquisition of data: VK. Data analysis plan developed by: VK, KS, IB. Statistical analysis conducted by: IB, VK. VK drafted the manuscript under supervision of KS. All authors made substantial contribution to interpretation of data and several critical revisions of the manuscript: VK, IB, KS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication related to this article.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The authors declare that the study has been registered and accepted by Jagiellonian University Ethics Committee (agreement No. 122.6120.31.2015) and it was conducted in line of the current laws, meeting the standard requirements.

Informed consent

Based on the Jagiellonian University Ethics Committee approval, the informed consent was obtained from all settings where the study was conducted. Data collected in the study were analyzed anonymously by researchers without any possibility of identification of individual residents. Formal consent of individuals is not required for this type of study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kijowska, V., Barańska, I. & Szczerbińska, K. Health, functional, psychological and nutritional status of cognitively impaired long-term care residents in Poland. Eur Geriatr Med 11, 255–267 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-019-00270-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-019-00270-5