Abstract

Purpose

Large-scale nationwide comparative studies of older adults with cognitive impairment (CI) in long-term care institutions (LTCI) hardly exist in Poland. This paper compares the prevalence of CI and its symptoms in residents of nursing homes (NHs) and residential homes (RHs) in Poland.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey of a country-representative sample of 23 LTCIs was conducted in the years 2015–2016. In total, 1587 residents were included: 626 residents in 11 NHs and 961 residents in 12 RHs. All individuals were assessed with a Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) using a cutoff of ≥ 2 points to define the presence of CI. Descriptive statistics and Chi square test were used.

Results

The median age was 80 years, 67.7% were women. Overall, 65.2% of residents (n = 1035) were identified as having CI, ranging from 59.2% in RHs to 74.5% in NHs, after excluding residents in a coma. Furthermore, the prevalence of severe CI was significantly higher in NHs than in RHs (respectively, 41.2 and 20.5%). It concerned specifically impairment of memory: procedural (72.3 vs 55.2%), long-term (56.5 vs 32.1%), short-term (46.8 vs 33.4%), and situational one (40.2 vs 26.4%), as well as problems with being understood by others (44.6 vs 24.7%) and severely impaired capacity of daily decision making (44.7 vs 21.5%).

Conclusions

A high prevalence of CI was found in both LTCI types, but its severity differed, with statistically significantly higher rates in NHs compared to RHs. Therefore, we call for more attention to be paid to better recognition of CI in LTCI residents, regardless of the facility type.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Poland in the last 20 years, an increase in the number of old people living alone has been observed due to changes in the traditional model of the family and economic migration. Nowadays, 18.2% of the population aged 65 years and older is living alone and many of them, when their health declines and/or social condition gets worse, require professional long-term care (LTC) provided either in their community or in an institution. In 2015, approximately 0.9% of the Polish population at the age of 65 years and older received LTC in institutional settings (other than hospitals), well below the OECD-21 (eng. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) average of 4.1% [1, 2]. According to official reports, in Poland every year approximately 100 thousand chronically ill people and/or older adults, with complex medical and nursing needs, benefit from stationary LTC services, both in the health and social care sectors. Most of them are older adults with multiple chronic diseases, including cognitive decline and dementia [3, 4].

Cognitive impairment (CI) is a syndrome that encompasses several symptoms including changes in memory, attention, executive function, learning, and language capabilities that negatively influence the quality of life, the character of personal relationships, and the capacity for making informed decisions about health care and other various aspects of daily life [5]. In most cases, it develops as a result of Alzheimer disease or other neurodegenerative pathology leading to dementia. There is evidence that CI is positively associated with admission to a long-term care institution (LTCI) [6, 7], yet data about its prevalence vary between countries and the types of setting, ranging from 31.3% up to even approximately 90% [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. There is no such data for Poland. Most of the previous studies included a small number of residents [18,19,20,21], referred only to selected medical problems [18, 22, 23], used different research tools [21, 24], were narrowed to one type of setting [25, 26], or combined the two types of institutions as one group [27]. In fact, a direct comparison at the national and international levels based on these data is impossible. Thereby our understanding of the prevalence of cognitive deficits in the LTC population in Poland is very much limited, and the diversity of institutions adds to the inconsistency of reports on CI and dementia.

There are two types of LTCIs in Poland, which are organized, managed, and founded under two separate ministries (the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy), regulated by different laws and providing a different range of services. Consequently, LTCIs are targeted at different types of residents, with admission criteria simply based on the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) measured with the Barthel Index (BI), which places only highly disabled residents (with BI less than 40) in nursing homes (NH), whereas less ADL-dependent residents typically remain in residential homes (RH) for chronically ill and disabled people for an extended period of time. For more details on the differences between NHs and RHs, please refer to supplementary table A in the supplementary material. However, CI assessment is not used as an admission criterion. Moreover, institutions devoted specifically to people living with dementia are very rare, so residents with CI tend to be located in different settings together with other chronically ill patients.

The aim of this study was to compare the prevalence and severity of CI among residents in two large cross-sectional samples of LTC institutions. Furthermore, we explored differences between NH and RH residents in terms of cognitive functioning. We believe that our findings provide some practical conclusions for better identifying patients with CI residing in LTC institutions, to recognize their needs, and address appropriate services. That seems to be an important and meaningful challenge for the LTC sector in Poland.

Methods

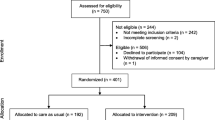

We conducted a cross-sectional study of residents in a representative number of LTCI from all six regions in Poland, in 2015. The inclusion criteria for the setting were based on the European Association of Palliative Care (EAPC) definition of the LTCI that describes it as a collective institutional setting where care—on-site provision of personal assistance with activities of daily living (ADL) and on-site or off-site provision of nursing and medical care—is provided for older people who live there, 24 h a day, 7 days a week, for an undefined period of time [28]. Since dementia and CI are highly correlated with age, only settings providing care for older and chronically ill persons were targeted. At the end of 2014, in Poland there were in total 985 such facilities (487 NHs providing care for 51,500 residents yearly and 498 RHs providing care for 51,200 residents yearly) with approximately 60 thousands of beds at their disposal [3, 4]. Based on the assumption of the number of the LTCF population with cognitive decline at 50%, and the number of recipients of LTC services at 100 thousand per year, we had calculated a sample size of 1056 respondents as required to assess the prevalence of cognitive impairment in the LTC population with an accuracy of three points. On this basis, while taking the median number of 52 beds in LTCls in Poland, we came to the number of 21 settings as minimal to reach representativeness (median beds = 52, estimated number of people = 1092). First, we performed a random sampling of 100 LTCI out of 985, made in 48 strata (according to four variables: six country regions, two types of settings: NH and RH, small and big size according to median bed number and public or private ownership status). Taking into account the rather low response rate, found to be in the surveys using mailed questionnaires, we had sent invitations to all 100 LTC settings. In total, we received a written response, together with a questionnaire concerning the LTC setting characteristics, filled out from 49 LTCls, out of which 23 agreed to participate in a study of all residents, and 26 definitely declined. The sampling procedure met minimum requirements regarding the expected number of both facilities and the residents. We also conducted a non-response analysis by comparing the LTCI characteristics of settings, which did and did not return questionnaires. The non-response analysis did not reveal significant differences between facilities included in the study (n = 23) and those which declined (n = 26) in terms of their ownership status, number of beds, length of stay in the institution, level of dependency of residents measured with the use of Barthel Index and the number of patients requiring full assistance in eating, ratio of staffing level, access to physicians, wards for residents with dementia and specialized equipment for residents. The study received approval from the University Ethical Committee, and written consent, as required, was granted by 11 NHs (with doctors, nurses and care assistants available 24 h/7 days a week) and 12 RHs (with nurses or care assistants available 24 h/7 days a week). The researcher visited all the settings and introduced the methodology. Next, all the residents at each institution were assessed with the InterRAI Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) that assigns residents to cognitive performance categories, ranging from a score of ‘0’ to ‘6’, where higher scores indicate worse cognition [29]. This scale has been shown to have a high correlation with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [29,30,31] and has been widely used [32,33,34]. Its high comparability with MMSE confirms that a CPS score ≥ 2 is equivalent to a diagnosis of cognitive impairment [35] or an MMSE score of ≤ 19 [36]. For this analysis, the usual cutoff of 2 points or more was used to define the presence of cognitive decline, which was categorized as follows: mild impairment (CPS score 2), moderate impairment (CPS score 3–4) and severe impairment (CPS score ≥ 5). A score of 0–1 represents normal or nearly intact cognitive function. The CPS score is derived from four variables—two cognitive items (asking for short-term memory and decision making), one communication item (measuring the ability to make oneself understood) and one ADL item (eating performance) [37] (see description of CPS items in table B in the supplement). Assessment of cognitive status was performed by a trained nurse (or psychologist)—one from each setting—on the basis of a 3-day observation of residents during everyday care routines. It was supported by information obtained from relatives or other staff members, if needed. The manager or another administrator from the institution filled in a questionnaire concerning the characteristics of an LTCI.

The descriptive analysis of qualitative variables was conducted using frequencies and percentages. We used medians and quartiles due to skewed distribution of the quantitative variables. To compare the two groups of NH and RH populations, we applied the Mann–Whitney U test in relation to quantitative variables (e.g., age, length of stay) and the Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate, for qualitative variables. Differences were considered statistically significant if the p value was less than 0.05. All the analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 software for Windows (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL).

Results

The entire study sample comprised 1587 people, 626 residents in NHs and 961 residents in RHs of median age 80 years, living in 23 settings. Overall, 93 residents (5.9%) were not able to make daily decisions, since they were nonresponsive due to indiscernible consciousness or coma. We called them in the study as “residents in coma” and excluded them from participant characteristics and further analysis of the specific CPS items.

Characteristics of LTC institutions in Poland

Data were collected from 23 settings: 11 NHs and 12 RHs, among which 91.7% RHs and 36.4% NHs were public non-profits. We found significant differences between these two types of settings in human resources. However, access to psychological support, occupational therapy and specialized equipment (except drug administration pumps) did not differ significantly between the institution types. None of the NHs and only 2 RHs (16.7%) had separate wards for residents with dementia at their disposal. We found more statistically significant differences between NHs and RHs in terms of residents’ ADL capacity and average length of residents’ stay in LTCI (Table 1).

Characteristics of LTC residents in the NHs and RHs in Poland

After excluding residents in a coma, the study sample comprised 1494 people (577 in 11 NHs and 917 in 12 RHs) of median age 80 years. Most of them were female (67.7%), and 63.3% were aged 75 and older. In comparison to RH residents, the NH residents were more often female (71.9 vs 65.0%; p = 0.005), were older (Me: 80 vs 79 years; p = 0.016), and stayed at LTCI for a shorter time. The median length of stay in RHs was above 3.5 years, that is, more than four times longer compared to NH residents (Me: 45 vs 185 weeks, p < 0.001). For 65.2% NH residents and 89.1% RH residents, the length of stay in the institution was longer than 6 months. Overall, almost every other resident, regardless of the type of the institution, had a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease or dementia officially recorded in medical files (n = 1494), and it is interesting that it still concerns only 62.8% of residents with CI, assessed with CPS (CPS ≥ 2; n = 1035). We found that the characteristics of residents with cognitive impairment (excluding residents in coma) admitted to NH and RH significantly differed also in other factors such as age, gender, and length of stay (as presented in Table 2). Such differences were also found in the characteristics of all LTC residents divided into five groups by CPS score including residents in coma, separately for NHs and RHs, and in total, as outlined in Table 3 and Fig. 1.

Prevalence and characteristics of cognitive impairment in NH and RH residents in Poland

Our study showed a high prevalence of CI assessed with the CPS (CPS ≥ 2) in LTC residents in Poland (overall 65.2% residents, n = 1035), ranging from 74.5% in NHs to 59.2% in RHs. The prevalence of CI and its severity were substantially higher in NH residents compared to RH residents. This particularly concerned persons with severe CI, with a CPS score of 5 or 6 (p < 0.001). Statistically significantly more residents with coma were in NHs than in RHs (see Fig. 2). No difference in the prevalence of CI between females and males in both types of LTCI was observed (in 80.7% females and 80.9% males in NHs; p = 0.97; versus in 63.9% females and 58.6% males in RHs; p = 0.11). Yet, we observed differences between the groups in the prevalence of the decline of specific functions analyzed with CPS items. A greater proportion of residents in NHs experienced a severe decline in daily decision making, short-term memory, and being understood by others compared to RHs residents. They also more often required extensive help in eating (Table 4).

The severity of decline in cognitive skills for daily decision making was statistically significantly higher among NH residents (p < 0.001). Overall, 30.5% of residents never or rarely made decisions, ranging from 44.7% in NHs to 21.5% in RHs. A similar group of 30.5% of NH residents and 30.6% of RH residents made poor or unsafe decisions, and cues/supervision was necessary at those times or at all times to plan, organize, and conduct daily routines. Only 24.8% in NHs compared to 47.9% in RHs were able to make decisions in organizing daily routines in a consistent, reasonable, and safe way or experienced some difficulty only when faced with new tasks or situations (with no decline in familiar situations).

NH residents substantially more often showed problems with their ability to remember both recent and past events and to perform sequential activities compared to RH residents. This latter problem (procedural memory) was observed among 72.3% NH and 55.2% RH residents (p < 0.001). The problems least frequently presented in both types of LTC settings were those with situational memory, but still they appeared significantly more often among NH residents.

Furthermore, the study demonstrates statistically significant differences in residents’ ability to communicate with other patients and staff members (p < 0.001). Overall, 47.0% of the studied LTC residents (ranging from 62.5% in NHs to 37.8% in RHs) had limited self-expression to be understood by others. About 17.9% residents in NHs and 13.1% in RHs had difficulty finding words or finishing thoughts, and prompting was usually required. Another 21.0% NH and 13.6% RH residents were affected by a limited ability to make concrete requests regarding basic needs such as food, drink, sleep, toilet, or pain. Nearly one out of four NH residents was rarely or never understood compared to 11.1% of residents in RHs. Understanding of these residents was limited to staff interpretation of highly individual, person-specific sounds or body language.

The proportion of residents requiring extensive assistance in eating or who was totally dependent on others for it was high in both groups; however it was nearly doubled among NH residents compared with their RH peers. Summarizing, the residents in both LTCI types had a broad array of presenting issues of cognitive decline, yet with a statistically significant predominance among NH residents.

Discussion

The life span extension observed in most countries results in an increase of the number of people in old age [38,39,40,41], which is associated with accelerated growth of the number of individuals living with cognition disorders. Nowadays, although CI and dementia have become one of the biggest challenges for LTC, large-scale nationwide comparative studies on cognitive deficits in LTC residents hardly exist in Poland. From the standpoint of cognitive functioning, the findings from our study complement the existing knowledge about the prevalence of CI in the LTC population in Poland [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. We found that the overall CI prevalence in Polish LTCIs (65.2%) was very similar to results obtained in other European countries by Gutiérrez et al. [42], Onder et al. [12], Björk et al. [9], and Stange et al. [10], respectively, 76.0, 68.0, 66.6, and 59.0%, as well as to the American reports by Mansbach et al. [8]—78.9% (long-stay patients) and 61.4% (short-stay patients). Higher percentages of people with a CI diagnosis were found in two large-scale studies in Norwegian NHs (80.5, 82.0%) [11, 43] and among Irish NH residents (89.0%) [13].

In our study, only 62.8% of LTC residents with CI had a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia. Similar findings (55.0 and 44.7%) were reported by Selbæk et al. [11] and Kinley et al. [14] and were even higher than the results reported by Gutiérrez et al. [42] and Cahill et al. [13], where only one out of three residents had been diagnosed with dementia. Thus, our findings may suggest that within the surveyed LTCI, there may have been residents with CI with non-dementia background or undetected dementia, both in NHs and RHs.

Our results, apart from their statistical feature showing high prevalence of CI in both types of settings, support the view that in fact NH residents and RH residents differ in their deficits and preserved strengths (CI of 74.5 vs 59.2% of residents, respectively). The share of residents with mild, moderate, and severe CI was significantly different between these two groups. NH residents had a significantly lower level of cognitive functioning with a higher prevalence of severe and moderate CI compared to RH residents. At a more granular level, both groups demonstrated a high occurrence of deficits in memory, communication, and decision making. However, RH residents performed better than their NH peers.

This clear message should encourage health-care organizers to apply cognition assessment in addition to the Barthel Index reference criterion to a certain type of LTC institution. We fully support the report of the Supreme Audit Office on functioning LTC in Poland (2010), which also pointed out admission criteria to LTC as a weak point of the system [44]. Oversimplified admission criteria result in the danger that residents with CI are not always referred to the right institution or that they do not receive appropriate care. Moreover, the result of cognitive functioning assessment performed by staff should trigger implication of the tailored dementia care programmes adjusted to the degree of CI and the type of setting. However, differences between NHs and RHs in their organization structure and human resources result in a different spectrum of services and the limited accessibility of physicians and other professional staff in RHs. In addition, the availability of geriatricians in Poland is dramatically low. We suspect these facts may result in a possible bad impact on the quality of care for the LTC residents with CI.

This now seems to be the greatest challenge for the LTC sector in Poland, since both specialist programmes for residents with dementia and specialist dementia care settings are still very rare in our system. Thus, providing evidence about the high prevalence of CI both in NHs and RHs should alert managers to implement such services in practice. Reliable information on the number of residents with CI in LTC settings and on the severity of these deficits is crucial for health and care planners, so they can organize and provide optimal care for these residents. Consequently, it is necessary that NH and RH staff perform screening tests to detect disorders of cognitive functions, especially in these care organizations where a geriatrician is hardly available.

Study advantages and limitations

This is the first study in Poland conducted in a national representative sample of LTC institutions to collect data from a large number of residents. It provides unique information on the prevalence of CI in residents of NHs and RHs, which differ substantially in terms of organization and human resources. The study was performed in a short period of 3 months, and all residents were screened in each institution to avoid response bias and length-based sampling bias. However, to meet our goal of studying over 1500 residents in a short time, we had to narrow our assessment to a short questionnaire easily filled out by a selected staff person after 1 h training, based on observation of the resident instead of assessing all cognitive functions with a long tool, e.g., MMSE and a drawing clock test, which both need assessor’s experience. Consequently, only a few basic variables were collected. However, the characteristics of residents’ health status and care needs were studied later in-depth in the second wave of the study on the smaller random samples of residents with CI from these settings (the results will be published in another paper).

Conclusions

The results from our study showed the existence of a serious problem of a high proportion of LTC residents with impaired cognitive functioning. We found that CI prevalence is high both in NHs and RHs, but its severity differs, with higher rates in NHs. Furthermore, the rate of diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia is lower than the prevalence of CI. Therefore, we call for more attention to be paid to the better recognition of CI and dementia in LTC residents, regardless of the LTCI type.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- BI:

-

Barthel Index

- CI:

-

Cognitive impairment

- CPS:

-

Cognitive Performance Scale

- EAPC:

-

European Association of Palliative Care

- LTC:

-

Long-term care

- LTCI:

-

Long-term care institution

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- NH:

-

Nursing home

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- RH:

-

Residential home

References

OECD (2017) Health at a glance 2017: OECD Indicators. OECD Publ 2017. https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2013-en

OECD (2013) Health at a glance 2013: OECD Indicators. Paris: 2013. https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2013-en

Główny Urząd Statystyczny (2016) Pomoc społeczna i opieka nad dzieckiem i rodziną w 2015 roku (eng. Social assistance, child and family services in 2015). Warszawa: 2016

Główny Urząd Statystyczny (2017) Zdrowie i ochrona zdrowia w 2016 roku (eng. Health and health care in 2016). Warszawa: 2017

Wagster MV, King JW, Resnick SM, Rapp PR (2012) The 87%: guest editorial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 67:739–740. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gls140

Wang S-Y, Shamliyan TA, Talley KMC, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL (2013) Not just specific diseases: systematic review of the association of geriatric syndromes with hospitalization or nursing home admission. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 57:16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2013.03.007

Banaszak-Holl J, Fendrick AM, Foster NL, Herzog AR, Kabeto MU, Kent DM et al (2004) Predicting nursing home admission: estimates from a 7-year follow-up of a nationally representative sample of older Americans. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 18:83–89

Mansbach WE, Mace RA, Clark KM, Firth IM (2017) A comparison of cognitive functioning in long-term care and short-stay nursing home residents. Ageing Soc 37:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X15000926

Björk S, Juthberg C, Lindkvist M, Wimo A, Sandman PO, Winblad B et al (2016) Exploring the prevalence and variance of cognitive impairment, pain, neuropsychiatric symptoms and ADL dependency among persons living in nursing homes. A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 16:154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0328-9

Stange I, Poeschl K, Stehle P, Sieber CC, Volkert D (2013) Screening for malnutrition in nursing home residents: comparison of different risk markers and their association to functional impairment. J Nutr Health Aging 17:357–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-013-0021-z

Selbæk G, Kirkevold Ø, Engedal K (2007) The prevalence of psychiatric symptoms and behavioural disturbances and the use of psychotropic drugs in Norwegian nursing homes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:843–849. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1749

Onder G, Carpenter I, Finne-Soveri H, Gindin J, Frijters D, Henrard JC et al (2012) Assessment of nursing home residents in Europe: the Services and Health for Elderly in Long TERm care (SHELTER) study. BMC Health Serv Res 12:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-5

Cahill S, Diaz-Ponce AM, Coen RF, Walsh C (2010) The underdetection of cognitive impairment in nursing homes in the Dublin area. The need for on-going cognitive assessment. Age Ageing 39:128–131. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afp198

Kinley J, Hockley J, Stone L, Dewey M, Hansford P, Stewart R et al (2014) The provision of care for residents dying in UK nursing care homes. Age Ageing 43:375–379. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft158

Hockley J, Watson J, Oxenham D, Murray SA (2010) The integrated implementation of two end-of-life care tools in nursing care homes in the UK: an in-depth evaluation. Palliat Med 24:828–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216310373162

Helvik A-S, Engedal K, Benth JŠ, Selbæk G (2015) Prevalence and severity of dementia in nursing home residents. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 40:166–177. https://doi.org/10.1159/000433525

OECD/European Commission (2013) A good life in old age? Monitoring and improving quality in long-term care. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264194564-enIS

Bońkowski K, Klich-Rączka A (2007) Ciężka niesprawność czynnościowa osób starszych wyzwaniem dla opieki długoterminowej severe functional impairment in the elderly as a challenge at long-term care. Gerontol Pol 15:97–103

Pytka D, Doboszyńska A, Syryło A (2012) Ocena stanu psychofizycznego pacjentów Zakładu Opiekuńczo—Leczniczego “Caritas” Archidiecezji Warszawskiej (eng. Evaluation of psychophysical condition of patients attending the “Caritas” Health Care Centre of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Warsaw). Zdr Publ 122:155–159

Wdowiak L, Stanisławek D, Stanisławek A (2009) Jakość życia w stacjonarnej opiece długoterminowej. Med Rodz 12:49–63

Wróblewska I, Iwaneczko A (2012) Jakość życia pensjonariuszy Domu Pomocy Społecznej ‘Złota Jesień’ w Raciborzu—Badania własne. Fam Med Prim Care Rev 14:573–576

Jóźwiak A, Guzik P, Wysocki H (2004) Niski wynik testu Mini Mental State Examination jako czynnik ryzyka zgonu wewnątrzszpitalnego u starszych chorych z niewydolnością serca. Psychogeriatria Pol 1:85–94

Górska-Ciebiada M, Saryusz-Wolska M, Ciebiada M, Loba J (2015) Łagodne zaburzenia funkcji poznawczych u chorych na cukrzycę typu 2 w wieku podeszłym (eng. Mild cognitive impairment in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes). Geriatria 9:102–108

Pawlak A (2015) Jakość świadczonej opieki w ośrodkach całodobowego pobytu dla osób w wieku podeszłym. Fam Med Prim Care Rev 17:197–201

Kowalska J, Szczepańska-Gieracha J, Piątek J (2010) Zaburzenia poznawcze i emocjonalne a długość pobytu osób starszych w Zakładzie Opiekuńczo-Leczniczym o Profilu Rehabilitacyjnym. Psychogeriatria Pol 7:61–70

Kowalska J, Rymaszewska J, Szczepańska-Gieracha J (2013) Occurrence of cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms among the elderly in a nursing home facility. Adv Clin Exp Med 22:111–117

Kuźmicz I, Brzostek T, Górkiewicz M (2014) Występowanie odleżyn a sprawność psychoruchowa osób z zaburzeniami funkcji poznawczych, objętych stacjonarną opieką długoterminową. Probl Pielęgniarstwa 22:307–311

Reitinger E, Froggatt K, Brazil K, Heimerl K, Hockley J, Kunz R, Parker D, Husebo BS (2013) Palliative care in long-term care settings for older people: findings from an EAPC taskforce. Eur J Palliative Care 20(5):251–253

Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, Hawes C, Phillips C, Mor V et al (1994) MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol 49:M174–M182

Frederiksen K, Tariot P, De Jonghe E (1996) Minimum data set plus (MDS +) scores compared with scores from five rating scales. J Am Geriatr Soc 44:305–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb00920.x

Snowden M, McCormick W, Russo J, Srebnik D, Comtois K, Bowen J et al (1999) Validity and responsiveness of the minimum data set. J Am Geriatr Soc 47:1000–1004

Jones K, Perlman CM, Hirdes JP, Scott T (2010) Screening cognitive performance with the resident assessment instrument for mental health Cognitive Performance Scale. Can J Psychiatry 55:736–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371005501108

Hartmaier SL, Sloane PD, Guess HA, Koch GG, Mitchell CM, Phillips CD (1995) Validation of the minimum data set Cognitive Performance Scale: agreement with the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 50:M128–M133

Paquay L, De Lepeleire J, Schoenmakers B, Ylieff M, Fontaine O, Buntinx F (2007) Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of the Cognitive Performance Scale (minimum data set) and the mini-mental state exam for the detection of cognitive impairment in nursing home residents. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:286–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1671

Bula CJ, Wietlisbach V (2009) Use of the cognitive performance scale (CPS) to detect cognitive impairment in the acute care setting: concurrent and predictive validity. Brain Res Bull 80:173–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.05.023

Landi F, Tua E, Onder G, Carrara B, Sgadari A, Rinaldi C et al (2000) Minimum data set for home care: a valid instrument to assess frail older people living in the community. Med Care 38:1184–1190

Morris JN, Belleville-Taylor P, Fries BE, Hawes C, Murphy K, Mor V et al (2009) InterRAI long-term care facilities (LTCF) assessment form and user’s manual. Version 9.1. interRAI, Washington, DC

Jorm AF, Jolley D (1998) The incidence of dementia: a meta-analysis. Neurology 51:728–733

Unverzagt FW, Gao S, Baiyewu O, Ogunniyi AO, Gureje O, Perkins A et al (2001) Prevalence of cognitive impairment: data from the Indianapolis study of health and aging. Neurology 57:1655–1662

Rosenthal T (2009) Przewlekłe zaburzenia pamięci. In: Rosenthal TC, Williams MENB (eds) Geriatria. Wyd Czelej, Lublin, pp 291–313

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CRJ, Kawas CH et al (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7:263–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005

Gutierrez Rodriguez J, Jimenez Muela F, Alonso Collada A, de Santa Maria Benedet LS (2009) Prevalence and therapeutic management of dementia in nursing homes in Asturias (Spain). Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 44:31–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2008.10.002

Bergh S, Holmen J, Saltvedt I, Tambs K, Selbaek G (2012) Dementia and neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing-home patients in Nord-Trondelag County. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 132:1956–1959. https://doi.org/10.4045/tidsskr.12.0194

Najwyższa Izba Kontroli (2010) Informacja o wynikach kontroli funkcjonowania zakładów opiekuńczoleczniczych (eng. Report on the results of the control of the functioning of long-term care institutions in Poland). Number KPZ-410-09/2009, p 63–66. Warszawa

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the managers of long-term care institutions in Poland who allowed the study to be conducted in their settings and to the facilities’ nursing staff for participating in collecting the data.

Funding

This work was supported by the Jagiellonian University Medical College (Grant No. K/DSC/003080). Grant recipient: Violetta Kijowska, MPH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

The authors declare that the study has been registered and accepted by the Jagiellonian University Ethics Committee (Agreement No. 122.6120.31.2015) and it was conducted in line of the current laws, meeting the standard requirements.

Informed consent

Based on the Jagiellonian University Ethics Committee approval, informed consent was obtained from all settings where the study was conducted. Data collected in the study were analyzed anonymously by researchers without any possibility of identification of individual residents.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kijowska, V., Szczerbińska, K. Prevalence of cognitive impairment among long-term care residents: a comparison between nursing homes and residential homes in Poland. Eur Geriatr Med 9, 467–476 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0062-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0062-2