Abstract

Eutrophication due to uncontrolled discharge of sewage water rich in nitrogen and phosphorous is one of the most significant water quality problems world-wide. Nitrogen and phosphorous can be removed by activated sludge process, one of the widely applied technologies among other conventional methods for municipal wastewater treatment. However, such technology requires high capital and operational costs, making it unaffordable for many developing nations, including Ethiopia. This study aimed to investigate the performance of two high rate algal ponds (HRAPs) in nitrogen and phosphorous removal from primary settled municipal wastewater under high land tropical climate conditions in Addis Ababa. The experiment was run under semi-continuous feed for 2 months at hydraulic retention times (HRT) ranging from 2 to 8 days and organic loading rates ranging from 44.3 to 9.08 g COD/m2/day using two HRAPs 250 and 300 mm deep, respectively. In this experiment, Chlorella sp., Chlamydomonas sp., and Scenedesmus sp. in the class of Chlorophyceae were identified as the dominant species. The maximum TN and TP removal of 91.70 and 82.81% was achieved in the 300 mm deep HRAP during 8 and 6 day HRT operations, respectively. Increased HRT and pond depth increased nutrient removal but high chlorophyll-a biomass was observed in the 250 mm deep HRAP. Therefore, the 300 mm deep HRAP is promising for scaling up nutrient removal from municipal wastewater at a daily average organic loading rate in the range of 14.3–15.33 g COD/m2/day or 10.34–11.46 g BOD5/m2/day and a 6 day HRT. We conclude that HRAP is a dependable approach to remediate nitrogen and phosphorous from primary settled municipal wastewater in Addis Ababa climate with appropriate control of pond depth, organic loading rates and HRT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sewage water treatment is a major challenge in developing country due to the inadequacy of sanitation facilities (Wang et al. 2014). In Ethiopia, the level of wastewater management is low, even by sub-Saharan standards due to a general lack of sanitation infrastructure, skill and knowledge of wastewater treatment (De Troyer et al. 2016). As a result, large volumes of untreated wastewater are discharged to the environment every day. A survey by the Ministry of Water Irrigation and Energy (MoWIE) showed that only 7.3% of all sewage generated in Addis Ababa is treated to the secondary level (MoWIE 2015). The release of untreated waste into the ecosystem is an emerging threat for Ethiopia because most of the population depends on fresh water resources for its livelihood (Renuka et al. 2015). Furthermore, untreated sewage provides a breeding ground for many disease causing organisms, especially in urban areas.

Untreated wastewater contains high levels of organic and inorganic pollutants and its discharge can damage the receiving water in many forms, ranging from aesthetic to physico-chemical characteristics (Chan et al. 2009). Eutrophication due to uncontrolled discharge of sewage water rich in nitrogen and phosphorous is one of the most serious water quality problems world-wide. In sewage water, nitrogen exists mainly in the form of ammonia/ammonium ion, nitrite and nitrate, whereas phosphorous occurs mainly as orthophosphates, polyphosphates and organically bounded phosphates (García et al. 2002; Abdel-raouf 2012). High nitrogen level, in particular nitrate in drinking water, can cause a number of human health problems, such as methemoglobinemia in infants and cancer in adults (Mayo and Hanai 2014). Likewise, high ammonia concentration has a toxic effect on fish and many other aquatic organisms. Furthermore, ammonia can deplete dissolved oxygen concentration and can alter the microbial community structure in the aquatic environment.

Nitrogen and phosphorous can be removed by the activated sludge process, one of the widely applied technologies among conventional methods for municipal wastewater treatment. However, there are a number of limiting factors associated with such technology in developing nations, including the difficulty to procure initial capital investments, lack of reliable energy supplies, and lack of technical expertise, all of which are expensive commodities in these countries (Wang et al. 2014; Renuka et al. 2013; Olukanni and Ducoste 2011). Even after these technologies are built and put into operation, the removal process of N and P requires continuous chemical input, which is costly and in turn, produces large volumes of sludge that must be disposed of, often a tedious process (Olguín 2012). The algae-based wastewater treatment process, on the other hand, represents a potential alternative technology that has attracted considerable attention in recent years as a cost-effective and environmentally compatible method (Pittman et al. 2011).

Microalgae utilize large amounts of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous for their growth and further store excess nutrients within their cells for future use (Rawat et al. 2016). This ability allows them to remove nutrients at high rates when applied to wastewater treatment using semi-engineered systems such as oxidation pond and facilitative ponds (Cai et al. 2013). In addition, ammonia stripping and phosphate precipitation due to increased pH account for substantial amounts of nutrient removal, which is indirectly driven by algal photosynthetic activity (Garcia 2000; Martínez et al. 2000). The most common use of microalgae in wastewater treatment is in waste stabilization ponds (WSP) (Olukanni and Ducoste 2011; Kaya et al. 2007). Although WSP can reduce organic pollutants to acceptable levels at minimal cost and maintenance, slow reaction rate, requirements for large areas of land, inconsistent nutrient removal and high algal seston concentration in the effluent are often problematic (Mayo and Hanai 2014; Davies-Colley et al. 1995). These limitations may be attributed to non-optimal design features of WSP to support intense algal growth (Olguın 2003). High rate algal pond systems (HRAPs) may overcome reaction rate, increase treatment efficiency, reduce the size of the land area required and increase biomass production due to their better aeration and mixing system (Cho et al. 2017; Shen 2014).

HRAPs with shallow depth (0.2–0.5 m) with algal cells kept in suspension by a paddlewheel mixing system improved the removal of COD, suspended solids, and pathogens (Craggs et al. 2012). HRAPs are the most efficient reactor system for maximum utilization of solar energy and cost-effectiveness for commercial biomass production using wastewater resources (Olguín 2012). While biofuel production from microalgal biomass is being considered as the most suitable energy alternative in the current economic climate, a promising method of biofuel production from algal biomass is cultivating algae in an efficient reactor using nutrients from wastewater that ensure low cost treatments (Rawat et al. 2013). HRAPs are efficient reactors currently available for the dual applications of wastewater treatment and biofuel production, and their use has increased during the last few decades (Sutherland et al. 2014; Nurdogan and Oswald 1995). As in other pond systems, organic matter removal in HRAP wastewater treatment systems is the result of algae/bacteria symbiotic processes. Algal photosynthetic activity supplies oxygen for organic matter oxidation by bacteria and algae, in return, utilize CO2 produced from bacterial respiration for growth (Mun and Guieysse 2006). Furthermore, HRAP can provide consistent nutrient removal and efficient natural disinfection of pathogens in WSP (Craggs et al. 2012).

The performance of HRAP wastewater treatment is influenced by a variety of factors, including temperature, solar radiation, variable nutrient concentration and organic loading rates (Larsdotter 2006; Grobbelaar 2010). These factors need to be optimized, otherwise they can alter physical, chemical and biological processes in the system and, in turn, can compromise the development of microorganisms involved in pollutant removal and thus ultimately affect treatment efficiency (Assemany et al. 2015). However, negative influences of many physical/chemical factors can be minimized through modification of HRAP operational features, such as organic loading rate, pond depth and hydraulic retention time (Sutherland et al. 2015). Pond depth influences the physical, biological and hydrodynamic aspect of ponds. According to Sutherland et al. (2014), the volume of wastewater treated and the amount of light a microalgae receive are largely determined by pond depth and other factors such as biomass concentration and mixing regime. Furthermore, the depth of ponds can also affect the treatment efficiency by altering the synergetic balance between heterotrophic bacteria and autotrophic microalgae through organic carbon and oxygen exchanges (Lundquist et al. 2010).

Pond hydraulic retention time (HRT) is also an important parameter of proper pond design of HRAP and ultimately affects effluent quality and algal biomass production (Faleschini et al. 2012). Cromar and Fallowfield (1997) observed that phosphorous removal in agricultural wastewater increased from 69 to 93% in HRAP when HRT was increased from 5 to 7 days. However, they found chlorophyll-a to decrease from 1.76 to 1.01 mg/l at 5 and 7 day HRT, respectively. In another report, the removal of nitrogen from urban wastewater improved with increasing HRT in pilot HRAP operated for 1 year at variable HRT and 11 to 25 °C temperature range (Garcia 2000). Although various suggestions of HRT for HRAPs have been made (Rawat et al. 2016), several studies recommended HRT in the range of 3–10 days in different seasons and climatic conditions (Olguın 2003; Nurdogan and Oswald 1995; Mehrabadi et al. 2015). Depth, HRT and climate conditions also affect organic loading rate, as the loading rate is directly related to the ability of ponds to remain aerobic (Butler et al. 2017). According to USEPA (2011), HRT between 120 and 180 days are required for the BOD loading rate between 11 and 22 kg/ha/day, respectively, in winter at temperatures below 0 °C to achieve 95% BOD5 removal efficiency. This shows that many of the factors affecting the performance of HRAP are interrelated, suggesting that optimizing these parameters is critically important.

Various studies have tested HRAPs for the treatment of municipal, industrial and agricultural wastes (Park et al. 2011). Some studies have been carried out to optimize HRAP performance for wastewater treatment focusing on single operational feature such as depth, HRT, mixing system and organic loading rate (Garcia 2000; Sutherland et al. 2014; Cromar and Fallowfield 1997). These studies examined operational and environmental conditions for maximum algal growth and productivity, which are fundamental to the successful application of HRAP both for wastewater treatment and biomass production for economic use. Other factors in algal growth and productivity in HRAPs include organic loading rate and others, all of which are affected by weather conditions. Therefore, site specific studies under variable operational conditions need to adjust design criteria to local climate and weather conditions. Hence, this study aimed to determine the performance of HRAPs for nitrogen and phosphorous removal from primary settled municipal wastewater using two pond depths with different HRT and organic loading rate in the tropical highland climate of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Site and Wastewater Characteristics

Primary settled wastewater was used in the experiment. The wastewater was primary sedimentation chamber wastewater from a waste stabilization pond (WSP) located in Akaki/Kaliti wastewater treatment station in the southern part of Addis Ababa. The city is located at 2400–2500 m altitude and sub-humid tropical highland climate. The Akaki/Kaliti treatment system consists of two series of ponds, each consisting of one facultative pond, one maturation pond and two polishing ponds. The treatment plant receives daily about 7600 m3 of sewage water, which it discharges into the Little Akaki River after approximately 30 day HRT. The physico-chemical quality of the wastewater after primary sedimentation used in this study is shown in Table 1. In terms of organic content, the influent can be classified as weak, medium and strong wastewater (Metcalf-eddy 2003).

Experimental Setup

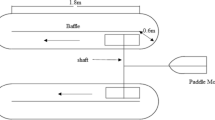

In order to assess the treatment performance of the pilot HRAPs as a function of depth and HRT, two similar HRAPs at two different water depth (250 and 300 mm) and corresponding working volume of 0.43 and 0.52 m3 were constructed. The pilot unit ponds were constructed from locally available materials with the following dimensions: width 0.6 m, length 1.8 m and illuminated surface area 2.0826 m2. Two three-paddlewheels, each 0.28 m in diameter and made from stainless steel, were locally constructed for mixing the wastewater and mounted to a 4 m long metal shaft. The two HRAPs were placed parallel to each other in a way that was suitable for the movement of the water in the two ponds with the metal shaft at the same rotational speed (Fig. 1). The shaft was driven by a 0.1 kW electric motor with a speed control to provide 0.2 m s−1 horizontal water velocity. The pond bottom was lined with plastic geomembrane to prevent infiltration of wastewater.

Experimental HRAP Operation

The two HRAPs were operated under four different HRTs: 2, 4, 6 and 8 days. The range of the depth and HRT operational parameters was chosen based on the recommendations by various studies of HRAP reactors (Olguın 2003, 2012; Nurdogan and Oswald 1995; Mehrabadi et al. 2015). Initially, both HRAPs were operated in batch mode for 10 days to allow stabilization of algae in the ponds as described by Kim et al. (2014), and then switched to semi-continuous mode. The daily influent flow rate to maintain a semi-continuous mode was calculated using working volume and HRT. Accordingly, 215L, 108L, 72L, 54L in the 250 mm deep and 258.4L, 130L, 86L, 65L in the 300 mm deep HRAP were exchanged daily with algal culture during 2, 4, 6 and 8 day HRT operations, respectively. The corresponding average organic loading rates at each HRT based on the influent wastewater characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Fresh wastewater after sedimentation in the primary sedimentation chamber was pumped to a 500L tank installed near the experimental facility. After taking a 250 ml sample using a clean plastic bottle for laboratory analysis, respective prescribed volumes of wastewater were measured and exchanged with equal volumes of culture during the semi-continuous operation between 10:00 a.m. and 10:30 a.m. every day. The experiment was run for 2 months from March to April, 2016, approximately for 15 days under each HRT. Before starting the semi-continuous experiment, both HRAPs were pre-cultured with 10L of indigenous wastewater containing the algae consortia Chlorella sp., Chlamydomonas sp. and Scenedesmus sp. obtained from the effluent of a maturation pond and allowed to operate in batch mode for 10 days to allow the stabilization of algae in the pond. On the 10th day, the concentration of algal biomass exceeded 1 g/l which, according to Kim et al. (2014), can be acclimatized to the organic and nutrient loading rate during continuous process treatment.

Experimental Control and Nutrient Measurements

Grab samples from each HRAP effluent were collected every 2 days for laboratory analysis of nutrients using 250 ml sampling between 10:00 and 10:30 a.m. throughout the course of the experiment. All nutrient samples were pre-filtered through Whatman GF/C filters and the analytical method was used for these parameter following standard procedures outlined by the APHA (2005). Accordingly, orthophosphate and TP were analyzed by the ascorbic acid method, nitrate by the cadmium reduction method, and ammonia by the ammonia salicylate method. Other physical parameters were measured daily onsite; pH by (HI 9024 microcomputer pH meter; HANNA instruments) TDS conductivity and salinity by (SX713 Cond/TDS/Sal/Res meter; HANNA instruments) and dissolved oxygen by an oxygen meter (Co-411 ELMEIRON) throughout the experimental period.

Species and Chlorophyll Analysis

Three major algal species resident in the experimental ponds were identified at the genius level with the help of an inverted microscope (Leica model) equipped with a Leica microscopic camera at a magnification of 400× using various identification keys (2005). Chlorophyll-a was determined spectrophotometrically according to the monochromatic method of Lorenzen (APHA 2005). Then 150 ml of samples were filtered through Whatman GF/F filters for the determination of total chl-a. Pigments of cells retained on the filter papers were extracted in 90% acetone for 24 h in the dark at 4 °C after homogenization. Chl-a concentration was determined using the following formula by Lorenzen (1966):

where \(V_{e}\) = volume of extract in milliliters V = Filtered volume in liter L = Cuvettes light-path in centimetres \({\text{E}}_{{665{\text{b}}}}\) = Optical density before acidification \({\text{E}}_{{665{\text{a}}}}\) = Optical density after acidification \({\text{E}}_{{750{\text{b}}}}\) = Optical density for light scattering before acidification \({\text{E}}_{{750{\text{a}}}}\) = Optical density for light scattering after acidification.

Finally, each analysis was made in triplicate. All data points represent the mean of replicate measurements except where noted. Finally, the percentage reduction was calculated based on the following equation:

Weather Condition

Daily solar radiation data were obtained from CAMS McLean v2.7 Satellite model at 8.77565N and 38.85E in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (http://www.soda-pro.com/web-services/radiation/cams-mcclear). Daily temperature data were provided from the nearby meteorological station in Akaki/Kaliti. The minimum and maximum daily solar radiation from March to April was 7.46 and 8.35 kW/m2/day, respectively. The minimum and maximum daily air temperature between March and April was 23 and 31 °C, respectively. March–May are the driest months (spring season) in Addis Ababa. Review of a meteorological record showed that the maximum solar irradiation and temperatures occured during spring. The temperature and radiation data recorded during the experimental period fall in the favourable range for most microalgal species (Mun and Guieysse 2006).

Data Analysis

The software package, SPSS Statistics 21 were used to perform the statistical analysis. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used in the case of replicate measurements. Paired t test was used to evaluate the difference in mean organic removal between the two treatments at 5 and 1% significant levels. Pearson correlation was used to evaluate the relationship between variables. Microcal origin (8.0) was used for data plotting and graphs.

Results and Discussion

Environmental Variables and Chlorophyll-a Production

Culture pH, DO and chlorophyll-a production were positively correlated to HRT in both HRAPs. The pH values increased to 9.02 and 8.97 from the same average initial pH value of 6.73 in the 250 and 300 mm deep HRAPs during the 9-day batch treatment period, respectively. The maximum pH values tested were 9.34 and 9.16 during 4-day HRT operation in the 250 and 300 mm depth HRAPs, respectively. Maximum DO production of 10.08 mg/l in 250 mm deep HRAP and 12.01 mg/l in the 300 mm deep HRAP were observed during 6-day HRT operation. The maximum chlorophyll-a levels in the 250 and 300 mm HRAPs were 2.91 and 2.76 mg/l during 4-day HRT operation, respectively.

While culture pH and DO were positively correlated with HRT in both HRAPs, a different trend was observed between pH and DO with respect to the operational depth. Higher DO production was observed in the 300 mm HRAP than the 250 mm HRAP, whereas higher pH values were observed in the 250 mm HRAP than the 300 mm HRAP (Table 3). This pattern may be explained in terms of carbon requirement, biomass concentration and pond depth. High chlorophyll-a concentration was observed in the 250 mm deep HRAP, which means higher carbon requirement, but considering the absence of external carbon addition, the available inorganic carbon from wastewater and paddling was more likely over consumed in the shallow HRAP and the rise of culture pH due to organic dissociation. Furthermore, higher chlorophyll concentrations coupled with carbon limitation can reduce photosynthetic efficiency at least during some parts of the day and result in less cumulative DO production in shallow ponds (Sutherland et al. 2014). In such case, deeper ponds are more favorable to keeping the pH at moderate values, which was also evidenced in our study with relatively low pH values in the deep HRAP.

On the other hand, areal chlorophyll-a biomass productivity increased with increasing pond depth after 2 day HRT operation. This suggests that algal growth in 300 mm HRAPs was less affected by inorganic carbon limitation due to pond depth while algal growth in the shallow HRAP was more constrained in spite of favorable mixing and light exposure Sutherland et al. (2014). Inorganic carbon concentration from wastewater was higher in the 300 mm HRAP since this was directly linked to the influent flow rate. Chlorophyll-a biomass of 2.6 mg/l in HRAP wastewater treatment was also reported by Cromar and Fallowfield (1997). However, they recorded a chlorophyll-a biomass of 3.49 mg/l when operating the same HRAP with higher carbon loading than in the present study. As discussed above, maintaining the availability of excess inorganic carbon is often a challenge in municipal wastewater algae cultivation as this limits algal photosynthetic efficiency via chlorophyll productivity and nutrient removal.

Effect of HRT on Nitrogen and Phosphorous Removal

The average concentration of TN, TP, NH4–N and dissolved reactive phosphorous (DRP) with corresponding removal efficiencies at each HRT operation are shown in Table 4. There was a general increase in nitrogen and phosphorous removal with increased HRT. TN removal was significantly correlated with HRT during the 2 and 6-day operations. The concentration of ammonium was reduced during 4-day HRT and remained low during 6 and 8-day HRT operations in both HRAPs (Fig. 2). TP and phosphate removal were also positively correlated with HRT during 2, 4 and 6-day operations of HRAPs. However, the concentration of total phosphorous increased during the 8-day HRT operation (Fig. 3). The slightly higher concentration total phosphorous observed after the system switched to 8 day HRT operation was probably due to algae biomass respiration in the sediment resulted in re-dissociation of phosphate back to the solution. A past study has also observed similar phenomena in pilot HRAPs operated for 1 year at HRT ranging from 3 to 10 days (García et al. 2002).

Theoretically, a minimum of 4-day HRT should be used to avoid washout according to the criteria HRT \(\ge\) \(\frac{1}{{\mu_{\text{AOB}} }}\), where \(\mu_{AOB}\) is the growth of ammonium oxidizing bacteria (USEPA 2011). Interestingly, the data from both HRAPs in our experiment fit this condition very well during 4, 6 and 8 days HRT operations by using some constants from other models such as, \({\text{K}}_{\text{n}}\) = 0.74 mg/l and \(\mu_{\hbox{max} }\) = 0.5/day from activated sludge model (Henze et al. 2000), and \(\varvec{\mu}_{{\varvec{AOB}}} =\varvec{\mu}_{{\varvec{max}}} \left( {\frac{{\varvec{NH}_{4} - \varvec{N}}}{{\varvec{NH}_{4} - \varvec{N} + \varvec{k}_{\varvec{n}} }}} \right)\varvec{ }\) (Metcalf-eddy 2003). This shows that nitrification can possibly be performed after 4-day HRT operations in both HRAPs in the presence of a suitable aerobic environment. We and others (Faleschini et al. 2012; Ahmad et al. 2011) reported that the intermediate denitrification stage may be suppressed due to the prevalence of DO in the reactor and nitrates as a byproduct of nitrification may be taken up by algae after 4 days operations. This possibility is strengthened by the positive correlation observed between chlorophyll-a biomass and HRT during 6-day HRT operations despite the depletion of NH4–N concentration early during 4-day HRT operation, in both HRPs. This phenomenon further indicates that algae shifted the nutrient source to nitrate after 6-day HRT following the near complete-exhaustion of NH4–N in the system after 4-day HRT operations.

Furthermore, culture pH and biomass production correlated with ammonia removal differently in the two HRAPs at different HRT. During the 2-day HRT operation, ammonia removal was negatively correlated in the 250 mm deep HRAP (r = − 0.10) and positively in the 300 mm deep HRAPs (r = 0.64) with chlorophyll-a production (Table 5). But the culture pH was positively correlated with ammonia removal in both HRAPs during this operation (r = 0.53 in the 250 mm deep HRAP and r = 0.96 in the 300 mm deep HRAP). During 6-day HRT operation, the correlation between ammonia removal and chlorophyll-a biomass production was negative in the 250 mm deep HRAP (r = − 0.34) and positive in the 300 mm deep HRAP (r = 0.67).

However, inverse relationships with chlorophyll-a biomass (r = 0.97 in the 250 mm and r = − 0.88 in the 300 mm deep HRAP) were observed between culture pH and ammonia removal in both HRAPs during the 6-days operation period (Table 5). These observations indicate that algal uptake may be dominant in nitrogen loss with some ammonia volatilization. In addition, culture pH remained slightly over 9 during the day time study period when there is an equilibrium shift within ammonium ion to ammonia gas (Nurdogan and Oswald 1995). Hence, taking into account the presence of high temperatures in our case, ammonia can be volatile and stripped from the solution by the paddlewheel mixing effect.

Phosphate removal was positively correlated with chlorophyll-a biomass during 2, 4 and 6-day HRT operations in both depth HRAPs except for a negative correlation observed in the 300 mm deep HRAP during 6-day HRT operation (Table 5). However, positive correlations between culture pH and phosphate removal were observed only during 2-day HRT operations in both the 300 mm deep HRAP and during 4-day HRT in the 250 mm deep HRAP. This pattern may indicate that the dominant process for phosphorous removal during 4 and 6-day HRT operations in both depth HRAPs involves some phosphate precipitation during 2-day HRT operations. Theoretically, at pH above 9.5 and high dissolved oxygen concentrations, phosphate elimination in wastewater is governed by precipitation (Cai et al. 2013). This does not seem to be significant in our study because the pH observed may not be sufficient to promote precipitation of phosphorous. Although many factors influence the dominance of the phosphorous removal mode, similar studies found that algal assimilation played a significant role in HRAP efficiency (Kim et al. 2014; Ahmad et al. 2011).

Effect of Pond Depth on Nitrogen and Phosphorous Removal

Although the removal of N and P improved with increasing HRT, marginally higher removal rates were achieved in the 300 mm deep HRAP than in the 250 mm deep HRAP during the study period. This can be explained partly by the higher photosynthetic rate in the shallow pond, which raised pH and DO values (Fig. 3) and possibly resulted in dissolved inorganic carbon depletion at early HRT in this system. Under such conditions, greater depth may be suitable to sustain CO2 in the water for relatively long times before outgassing to the atmosphere attributing for better nutrient removal (Lundquist et al. 2010). Algal photosynthetic uptake of N, P and inorganic carbon occurs in the stoichiometric ratio C:N:P ≈ 106:16:1 in nutrient unlimited environments, much higher than the C/N ratio in municipal wastewater (Hargreaves 2006).

The removal efficiencies of nutrients in wastewater treatment HRAPs observed in the present study were both similar and different to other studies. de Godos et al. (2009) reported 88% mean removal of N over 3 months (July–September) in a pilot HRAP treating diluted pig wastewater operated at 10 day HRT comparable to the present study. A study in Brazil reported an ammonia removal efficiency of 71% in pilot HRAPs treating municipal wastewater receiving effluent from an UASB digester (Santiago et al. 2013). A pilot HRAP operated for 1 year in an ambient environment in Spain with mean monthly temperatures ranging from 11 to 25 °C achieved NH4–N removal efficiencies of 57 and 73% at 4 and 7-day HRT using urban wastewater, respectively (Garcia 2000). Removal efficiencies of NH4–N in the range of 64–67% have been also reported in large-scale municipal wastewater treatment HRAPs operated at 4 day HRT algal assimilation was more dominant (Craggs et al. 2012).

Environmental Factors and HRAP Nutrient Removal

Various environmental factors, including temperature and solar radiation, as well as environmental variables like pH, and organic loading rate can affect nutrient removal and biomass production in pond systems. Temperature and solar radiation affect algal photosynthesis activity and then culture pH, which influences nutrient removal (Assemany et al. 2015). On the other hand, temperature and solar radiation influence the organic loading rates and hence affect HRAP operational and performance parameters (Cho et al. 2015, 2017). The average daily organic and nutrient loading rates estimated for the present study based on influent characteristics during 2, 4, 6 and 8-day HRT operations in the two HRAPs are shown in Table 2.

Table 6 shows the Pearson correlation between air temperature, surface loading and HRAP performance. Positive correlation of temperature and solar radiation with both chlorophyll-a biomass production and organic loading rate were observed during 6-day HRT operation in both HRAPs. During this HRT operation, the organic loading rate was also positively correlated with chlorophyll-a biomass production in the 300 mm deep HRAP and negatively correlated in the 250 mm deep HRAP (Table 6). Despite negative correlation of solar radiation to biomass production during 2 and 4 day HRT operations (Table 6), nutrient removal and chlorophyll-a production continued increasing in the two HRAPs at 2, 4 and 6 day HRT operations. One plausible reason for observation is that algae grown at longer HRT is more efficient in light conversion even with poor light penetration efficiency due to biomass attenuation effects (Sutherland et al. 2015).

It has been stated that the rate of carbon consumption can be determined from the rate of biomass production and drives the CO2 mass transfer gradient of air in photo bioreactor treatment without carbon addition (Judd et al. 2015). High chlorophyll-a biomass production rate and high pH record observed in the shallow pond relative to the 300 mm deep HRAPs together with the trends of pH correlation with nutrient removal during 2, 4 and 6 day HRT operations in 250 mm deep HRAPs (Table 5) may partly hint the occurrence of higher surface renewal rate in the shallow HRAPs than the 300 mm deep HRAPs. Considering better nutrient removal in the 300 mm deep HRAP, at longer HRT nutrient removal in shallow HRAPs more limited by availability of light due to self-shading and inorganic carbon in the absence of external aeration.

Organic loading rates in the range of 100–150 BOD5 kg/ha/day were recommended by Craggs et al. (2007) for such systems. The magnitude of the organic loading rate using 6-day HRT falls in the author’s recommended range. The concentrations of TN, TP, NH4–N, DPR and COD in the effluent were well below the value of influent discharge requirements in Ethiopia at 6-day HRT. However, the effluent \({\text{BOD}}_{5}\) at 6 HRT was 40 and 55% higher than the value stipulated in Ethiopia in the 250 and 300 mm deep HRAPs, respectively (data not shown). This is attributed to raw wastewater strength used in the influent. At high organic content, the pond may be converted into an anaerobic system, suppress algal activity and ultimately reduce oxygen availability for organic matter degradation by bacteria (Butler et al. 2017). Figure 4 shows that chlorophyll-a production increased continuously during 2, 4 and 6-day HRT operation but decreased during 8 day HRT operation in both HRAPs.

Taken together, this shows that an influent with an organic loading rate (kg \({\text{BOD}}_{5}\)/ha/day) of 91.5 and 109.3 can be treated in 250 and 300 mm deep HRAPs at HRT of 6 days, respectively, and may possibly give similar results if scaled up wastewater treatment systems. Furthermore, 6-day HRT can support the growth of ammonia oxidizing bacteria for nitrification, which further improves the removal of nitrogen. However, pre-treatment of the influent is necessary to reduce the organic loading rate to the required level.

Species Diversity in HRAPs

A group of Chlorophyceae constituted by Chlamydomonas, Chlorella and Scenedesmus sp., dominated the algal assemblage in both pilot HRAPs in the present study. These algal species are known to be the 10 most pollution tolerant microalgae (de Godos et al. 2009). The dominance of species can be determined by different factors, including retention time, loading rate and environmental variables such as incident surface radiation and temperature (Cromar and Fallowfield 1997). Hydraulic retention time, mode of operation and treatment depth were presumed to cause changes in algal species diversity in treatment ponds in the present study. However, no shift was observed in species dominance associated with changes in environmental variables of the experimental setting. The shallow operational depth and short circulation times of wastewater in the two pilot HRAPs due to mixing frequency that made the cells remain in suspension may have dominated other environmental factors as well as prevented species changes. Keeping the algae cells in suspension plays a critical role in maintaining the dominance of a species in the pond (Reynolds 2012).

Conclusions

In this study the performance of two HRAPs of different depth, operated under similar HRT for nitrogen and phosphorous removal from primary settled municipal wastewater. The removal of nitrogen and phosphorous increased with increasing HRT. However, the deeper pond was found to perform better in nutrient removal. This is attributed to the high carbon utilization in the shallow pond as a result of high level photosynthetic process. Considering TN, TP, NH4–N and DPR removal, operating the deeper pond at 6 day HRT can be taken as optimal HRT for large scale wastewater treatment application with organic loading rate. Furthermore, 6 day HRT also fits well to the theoretical expectation of sludge retention time for the growth of nitrifying bacteria in the system.

The production of biomass increased with increasing HRT. A group of Chlorophyceae comprised of Chlamydomonas sp., Chlorella sp. and Scenedesmus sp., were the dominant algal assemblage in both pilot HRAPs. The overall results suggest that indigenous algae/bacteria consortium in deeper HRAPs is a dependable approach for the remediation of nitrogen and phosphorous from municipal wastewater under the climatic conditions of Addis Ababa. However, the influent needs to be pre-treated when used for raw sewage treatment to bring down the organic loading rate to the required range of 14.3–15.33 g COD/m2/day and/or 10.34–11.46 g BOD5/m2/day to operate the 300 mm deep HRAP at 6 day HRT. Moreover, the algal biomass from the final effluent should be harvested before discharge to the environment. In this regards, gravity settling is considered to be a low-cost algal biomass harvesting mechanism for further use and water quality.

References

Abdel-raouf N (2012) Microalgae and wastewater treatment. Saudi J Biol Sci 19:257–275

Ahmad AL, Yasin NHM, Derek CJC, Lim JK (2011) Microalgae as a sustainable energy source for biodiesel production: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 15(1):584–593

APHA (American Public Health Association) (2005) Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 20th edn. American Public Health Association, Washington

Assemany PP, Calijuri ML, De Aguiar E, Henrique M, De Souza B, Silva NC, Santiago F (2015) Algae/bacteria consortium in high rate ponds: influence of solar radiation on the phytoplankton community. Ecol Eng 77:154–162

Butler E, Suleiman M, Ahmad A, Lu RL (2017) Oxidation pond for municipal wastewater treatment. Appl Water Sci 7:31–51

Cai T, Park SY, Li Y (2013) Nutrient recovery from wastewater streams by microalgae: status and prospects. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 19:360–369

Chan YJ, Chong MF, Law CL, Hassell DG (2009) A review on anaerobic—aerobic treatment of industrial and municipal wastewater. Chem Eng J 155:1–18

Cho D, Ramanan R, Heo J, Kang Z, Kim B, Ahn C, Oh H, Kim H (2015) Organic carbon, influent microbial diversity and temperature strongly influence algal diversity and biomass in raceway ponds treating raw municipal wastewater. Bioresour Technol 191:481–487

Cho D, Choi J, Kang Z, Kim B, Oh H (2017) Microalgal diversity fosters stable biomass productivity in open ponds treating wastewater. Sci Rep 7:1–11

Craggs RJ, Heubeck S, Lundquist TJ, Benemann JR, Zealand N, Luis S, Creek W (2007) Potential for algae biofuel from wastewater treatment high rate algal ponds in New Zealand. Water Sci Technol 7:1–8

Craggs R, Sutherland D, Campbell H (2012) Hectare-scale demonstration of high rate algal ponds for enhanced wastewater treatment and biofuel production. J Appl Phycol 24:329–337

Cromar NJ, Fallowfield HJ (1997) Effect nutrient loading retention time. J Appl Phycol 9:301–309

Davies-Colley RJ, Hickey CW, Quinn JM (1995) Organic matter, nutrients, and optical characteristics of sewage lagoon effluents. N Z J Mar Freshw Res 29(2):235–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.1995.9516657

de Godos I, Blanco S, García-Encina PA, Becares E, Muñoz R (2009) Long-term operation of high rate algal ponds for the bioremediation of piggery wastewaters at high loading rates. Bioresour Technol 100(19):4332–4339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2009.04.016

De Troyer N, Mereta ST, Goethals PLM, Boets P (2016) Water quality assessment of streams and wetlands in a fast growing east African City. Water 8:1–21

Faleschini M, Esteves JL, Valero MAC (2012) The effects of hydraulic and organic loadings on the performance of a full-scale facultative pond in a temperate climate region (Argentine Patagonia). Water Air Soil Pollut 223:2483–2493

Garcia J (2000) High rate algal pond operating strategies for urban wastewater nitrogen removal. J Appl Phycol 12:331–339

García J, Hernández-mariné M, Mujeriego R (2002) Analysis of key variables controlling phosphorus removal in high rate oxidation ponds provided with clarifiers. Water SA 28(1):55–62

Grobbelaar JU (2010) Microalgal biomass production: challenges and realities. Photosynth Res 106:135–144

Hargreaves JA (2006) Photosynthetic suspended-growth systems in aquaculture. Acquacult Eng 34:344–363

Henze M, Gujer W, Mino T, van Loosdrecht MC (2000) Activated sludge models ASM1, ASM2, ASM2d and ASM3

Judd S, Van Den Broeke LJP, Shurair M, Kuti Y, Znad H (2015) Algal remediation of CO2 and nutrient discharges: a review. Water Res 87:356–366

Kaya D, Dilek FB, Gökçay CF (2007) Reuse of lagoon effluents in agriculture by post-treatment in a step feed dual treatment process. Desalination 215:29–36

Kim BH, Kang Z, Ramanan R, Choi JE, Cho DH, Kim HS (2014) Nutrient removal and biofuel production in high rate algal pond using real municipal wastewater. J Microbiol Biotechnol 24:1123–1132

Larsdotter K (2006) Microalgae for phosphorus removal from wastewater in a Nordic climate. A doctoral thesis from the School of Biotechnology, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden

Lorenzen C (1966) A method for the continuous measurement of in vivo chlorophyll concentration. Deep Res 13:223–227

Lundquist ARBTJ, Woertz IC, Quinn NWT (2010) A realistic technology and engineering assessment of algae biofuel production. Energy Biosciences Institute, Berkeley

Martínez ME, Sánchez S, Jiménez JM, El Yousfi F, Muñoz L (2000) Nitrogen and phosphorus removal from urban wastewater by the microalga Scenedesmus obliquus. Bioresour Technol 73(3):263–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-8524(99)00121-2

Mayo AW, Hanai EE (2014) Dynamics of nitrogen transformation and removal in a pilot high rate pond. Water Water Resour Prot 6:433–445

Mehrabadi A, Craggs R, Farid MM (2015) Wastewater treatment high rate algal ponds (WWT HRAP) for low-cost biofuel production. Bioresour Technol 184:202–214

Metcalf-eddy (2003) Wastewater engineering treatment and reuse, 4th edn. McGraw-Hill Education, New York

MoWIE (Ministry of Water Irrigation and Energy) (2015) Urban wastewater management strategy. The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia

Mun R, Guieysse B (2006) Algal—bacterial processes for the treatment of hazardous contaminants: a review. Water Res 40:2799–2815

Nurdogan Y, Oswald WJ (1995) Enhanced nutrient removal in high-rate ponds. Water Sci Technol 31:33–43

Olguın EJ (2003) Phycoremediation: key issues for cost-effective nutrient removal processes. Biotechnol Adv 22:81–91

Olguín EJ (2012) Dual purpose microalgae—bacteria-based systems that treat wastewater and produce biodiesel and chemical products within a biorefinery. Biotechnol Adv 30:1031–1046

Olukanni DO, Ducoste JJ (2011) Optimization of waste stabilization pond design for developing nations using computational fluid dynamics. Ecol Eng 37:1878–1888

Park JBK, Craggs RJ, Shilton AN (2011) Wastewater treatment high rate algal ponds for biofuel production. Bioresour Technol 102(1):35–42

Pittman JK, Dean AP, Osundeko O (2011) The potential of sustainable algal biofuel production using wastewater resources. Bioresour Technol 102:17–25

Rawat I, Kumar RR, Mutanda T, Bux F (2013) Biodiesel from microalgae: a critical evaluation from laboratory to large scale production. Appl Energy 103:444–467

Rawat I, Gupta SK, Shriwastav A, Singh P, Kumari S, Bux F (2016) Microalgae applications in wastewater treatment. In: Bux F, Chisti Y (eds) Algae biotechnology: products and processes. Springer, Cham, pp 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12334-9_13

Renuka N, Sood A, Ratha SK (2013) Evaluation of microalgal consortia for treatment of primary treated sewage effluent and biomass production. J Appl Phycol 25:1529–1537

Renuka N, Sood A, Prasanna R, Ahluwalia AS (2015) Phycoremediation of wastewaters: a synergistic approach using microalgae for bioremediation and biomass generation. Int J Environ Sci Technol 12:1443–1460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-014-0700-2

Reynolds CS (2012) Environmental requirements and habitat preferences of phytoplankton: chance and certainty in species selection. Bot Mar 55:1–17

Santiago AF, Calijuri ML, Assemany PP (2013) Algal biomass production and wastewater treatment in high rate algal ponds receiving disinfected effluent. Environ Technol 34(13-14):1877–1885. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593330.2013.812670

Shen Y (2014) RSC advances treatment via algae photochemical synthesis for biofuels production. RSC Adv 4:49672–49722

Sutherland DL, Howard-williams C, Turnbull MH, Broady PA, Craggs RJ (2014a) Seasonal variation in light utilisation, biomass production and nutrient removal by wastewater microalgae in a full-scale high-rate algal pond. J Appl Phycol 9(26):1317–1329

Sutherland DL, Turnbull MH, Craggs RJ (2014b) Increased pond depth improves algal productivity and nutrient removal in wastewater treatment high rate algal ponds. Water Res 53:271–281

Sutherland DL, Montemezzani V, Howard-williams C, Turnbull MH, Broady PA, Craggs RJ (2015) Modifying the high rate algal pond light environment and its effects on light absorption and photosynthesis. Water Res 70:86–96

USEPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency) (2011) Principles of Design and Operations of Wastewater Treatment Pond Systems for Plant Operators, Engineers, and Managers, no. August. Cincinnati, Ohio: Land Remediation and Pollution Control Division National Risk Management Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development

Wang T, Omosa IB, Chiramba T (2014) Water and wastewater treatment in Africa—current practices and challenges. Clean Soil Air Water 42:1029–1035 (Review Article)

Acknowledgements

We like to thank Ethiopian Institute of Water Resources, Addis Ababa University, for supervising financial support given by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the USAID/HED Grant in the Africa-US Higher Education Initiative—HED 052-9740-ETH-11-01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alemu, K., Assefa, B., Kifle, D. et al. Nitrogen and Phosphorous Removal from Municipal Wastewater Using High Rate Algae Ponds. INAE Lett 3, 21–32 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41403-018-0036-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41403-018-0036-1