Abstract

This study aimed to examine the effects of “adaptive” bedtime routines on a child’s well-being, either directly or indirectly through sleep health. A web-based survey was conducted on 700 adults (321 male, 379 female, mean age = 39.98 years, SD = 6.33 years) responsible for preschool children aged 4–6 years old. Results of the mediation analysis showed that the bedtime routines index (BTR-Index[S]) could not confirm any significant regression coefficient with the total disturbance score of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ_TDS) (β = −0.063, p = 0.094) and the total sleep disturbance of Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ_TSD) (β = -0.013, p = 0.736) in a single regression analysis. Sobel’s test did not confirm any significant indirect effect (Z = −0.337, p = 0.736). As exploratory examination of the relationships between each of the items of BTR-Index(S) with SDQ_TDS and CSHQ_TSD, multiple regression analysis showed a significant positive partial regression coefficient for “Reading/sharing a story before bed” (β = 0.228, p = 0.006) and a significant negative partial regression coefficient for”Avoiding the use of electronic devices before bed” (β = −0.222, p = 0.011) towards CSHQ_TSD, with no significant partial regression coefficient identified for SDQ_TDS in any of the items. These findings suggest that bedtime routines do not directly either indirectly, through their sleep health, affect a child’s well-being. However, caregivers’ deliberate attempt to avoid stimuli that increases children’s wakefulness before bedtime may serve as protection for the child’s sleep health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bedtime routines are defined as, in the context of caregiver–child interactions, the observable, predictable and repetitive behaviors that occur in the hour or so before lights out, and before the child falls asleep [1, 2]. This concept has been viewed within the context of a family routines (childhood routines), supporting a child’s health and adjustment, as well as sleep rituals facilitating sleep onset and stabilizing sleep.

Family routines are defined as the “observable, repetitive behaviors which involve two or more family members and which occur with predictable regularity in the ongoing life of the family [3: pp.154].” The establishment of “adaptive” family routines are believed to enhance family cohesion, foster a sense of permanence and continuity among family members, mitigate the impact of stressors on health, and contribute to the development of interpersonal skills and social adjustment [3, 4]. Family routines are particularly crucial for a child’s well-being, encompassing sound development, good health, and emotional stability [3]. Bedtime routines are parts of family routines and the behaviors that occur within the context of caregiver-child interactions before sleep. Establishing “adaptive” bedtime routines during the quiet and intimate hours of the night are believed to be pivotal for a child’s development, well-being, and overall health [5].

Sleep rituals are activities designed to strengthen the association between bedtime and sleep by establishing a consistent pre-sleep routine. This fixed activities of spending the hours before bedtime are repeated daily, aiming to facilitate falling asleep by linking behavioral patterns to the sleep process. Bedtime routines, serving as sleep rituals, are utilized as a component of behavioral treatment for addressing bedtime problems and night waking in children, as well as for managing behavioral insomnia in childhood [6].

Interpretations of bedtime routines may vary depending on the context; however, there are common elements within the contents of “adaptive” bedtime routines. For instance, activities such as brushing a child’s teeth and reading/sharing story are considered “adaptive” both within the framework of family routines and as part of sleep rituals. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom using the Delphi method, six behaviors were identified as components of “adaptive” bedtime routines, namely, “brushing teeth before bed,” “time child goes to bed,” “reading/sharing a story before bed,” “avoiding food/drinks before bed,” “avoiding use of electronic devices before bed,” and “calming activities before bed” [5].

However, the relationship between these “adaptive” bedtime routines and their impact on a child’s well-being and sleep health remains unexamined. Moreover, numerous studies have demonstrated that children’s sleep health correlates with their cognitive development, social adjustment levels [7], and overall health [8]. These studies suggest that “adaptive” bedtime routines may not only directly contribute to a child’s well-being but also indirectly enhance it through improved sleep health.

In this study, a survey targeting caregivers of preschoolers in Japan was conducted and the direct or indirect effects of “adaptive” bedtime routines on a child’s well-being through their impact on sleep health were examined. Moreover, as exploratory analyses, we examined which specific bedtime routines were particularly associated with sleep health and well-being.

Materials and methods

This study procedure has been pre-registered with the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/ES7Q6).

Participants

Data from 700 adults (321 male, 379 female, average age = 39.98 years, SD = 6.33 years) responsible for preschool children aged 4–6 years old and meeting the eligibility criteria were analyzed.

Survey procedure

In this study, a web-based survey was conducted through Cross Marketing, Inc. Among Cross Marketing’s approximately 5.36 million registered monitors residing in Japan, 24,705 (as of September 20, 2020) were at least 20 years old and had children aged 4–6 years old. From this pool of monitors, 1500 samples were randomly selected. In November 2022, an email containing a link to the questionnaire website was sent to these selected individuals, inviting them to participate in the survey.

After consent to the study objectives and acknowledging the research ethics note on the first page, participants completed a series of questions related to demographic variables and a set of questions to confirm the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) raising at least one preschooler aged 4–6 years, (2) the child having no chronic illnesses or diseases requiring regular medication or medical management, and (3) the participant’s ability to subjectively assess their understanding of their child’s sleep habits (nighttime sleep and napping conditions) and daily life. Participants who met these eligibility criteria proceeded to the next page to complete the following assessments: (1) Bedtime Routines Index (BTR-Index) [5], (2) Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) for parents of 4–17-year-olds [9], (3) Japanese version of Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) [10, 11], and (4) items regarding the child’s sleep habits. In cases where participants had multiple children meeting the eligibility criteria, they were instructed to respond only regarding one of their children when answering questions about their child.

The questionnaire was designed to prevent submission if any items were left unanswered. Participants who completed the questionnaire in its entirety and submitted their responses received web service points (worth 20–50 yen), upon submission. The survey website was programmed to close automatically once 750 participants had submitted their responses. Among the submitted responses, any data identified as being provided at a pace faster than the standard set by Cross Marketing, Inc. were excluded as too quick responses. Subsequently, data from 700 randomly selected participants, derived from the remaining valid responses, were provided to the researchers.

Sample size rationale

The required sample size for mediation analysis to address the research question of this study was determined based on a previous study [12]. Assuming standardized coefficients from the independent variable to the mediating variable and from the mediating variable to the dependent variable are both set to 0.14 (considered small), with a p-value (α) set to 5% and a test power (1-β) of 80%, the Sobel test requires a sample size of n = 667.

Materials

Sociodemographic data

A set of items was developed to collect information regarding the participant’s age, sex, marital status, cohabitation with their spouse, and similar details. Additionally, another set of items was designed to determine the age in months, sex, and preschool attendance status of each of the participant’s children.

BTR-index

The BTR-Index requires respondents to provide a Yes (Implemented) or No (Not implemented) response to six bedtime routines deemed closely related to children’s development, well-being, and health, as defined and extracted using the Delphi method. Each item is weighted according to its importance, and the level of implementation of the bedtime routine considered “adaptive” for the child is rated on a scale of 0 to 100. The BTR-Index offers two assessment methods: one evaluates the bedtime routine between the caregiver and child over a span of seven nights (dynamic assessment), while the other assesses the bedtime routine based on the respondent’s rating of their routine on the day before completing the questionnaire (one-off static assessment). It has been reported that the difference between BTR-Indexes calculated using both evaluation methods is negligible, allowing for interchangeable use [5]. This study utilized the one-off static assessment (BTR-Index[S]) for its convenience in conducting a cross-sectional survey. The authors translated each item and instructional text into Japanese.

SDQ

The SDQ is a 25-item caregiver-evaluated questionnaire designed to comprehensively assess children’s emotional stability, adjustment, and mental health [9]. The SDQ comprises five factors: emotional symptoms (ES), conduct problems (CP), hyperactivity/inattention (HI), peer problems (PP), and prosocial behavior (PB). The Total Disturbance Score (TDS) is derived from the total scores of the four subscales (excluding PB), where higher scores indicate lower levels of well-being in the child.

CSHQ

The CSHQ is a self-administered questionnaire comprising 52 items [10, 11]. The Total Sleep Disturbance (TSD) can be calculated using 33 of the items from the CSHQ. In this study, CSHQ_TSD was used to measure the level of sleep health disturbance.

Items regarding a child’s sleep habits

A set of items was developed to inquire about the following aspects of children’s sleep habits: the number of days attending preschool per week (WD), sleep onset time on weekdays (SOw) and free days (SOf), and sleep end time on weekdays (SEw) and free days (SEf). This set of items was designed with reference to the Ultra-Short Version of the Munich Chrono Type Questionnaire [13, 14]. From the responses to these items, indicators such as sleep duration, the midpoint of sleep, and the level of social jetlag were calculated, drawing on previous studies [15, 16].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for each variable to provide an overview of the characteristics of the participants and their children. Subsequently, correlation coefficients were calculated to elucidate the relationship between bedtime routines and various aspects of sleep and well-being among children. Thereafter, mediation analysis was conducted using the Baron-Kenny method [17], with BTR-Index(S) as the explanatory variable, CSHQ_TSD as the mediating variable, and SDQ_TDS as the explained variable. This analysis aimed to examine the effects of bedtime routines on a child’s well-being, either directly or indirectly through sleep problems. Sobel’s test was used to assess indirect effects.

As exploratory analyses, multiple regression analyses using the forced entry method were conducted with BTR-Index items converted to dummy variables as explanatory variables and CSHQ_TSD and SDQ_TDS as explained variables (model 1). The aim of these analyses was to examine specific details of bedtime routines related to children’s sleep health and well-being. Subsequently, as a sensitivity analysis, multiple regression analyses in which family environmental factors (dummy variables for sex of participants, cohabitation with spouse, sex of children, and preschool attendance status: whether the child attends nursery school or not, and standardized age in months of children) were added as explanatory variables, were conducted (model 2).

All analyses were performed using R.4.3.0 [18]. Descriptive statistics, calculation of correlation coefficients, and tests of correlation coefficient were conducted using the psych package [19]. Mediation analysis and testing of the significance of indirect effects using Sobel’s test were conducted using multilevel package [20]. Finally, multiple regression analyses were carried out using the lm function and car package [21]. Significance level was set at a p-value of 5% for all analyses.

Ethical consideration

This study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Edogawa University prior to data collection (permission number: R04-014A).

Results

Characteristics of participants

The descriptive characteristics of each variable for the participants and their children, who are the subjects of their responses, are presented in Table 1.

Relationships between variables

The correlation matrix illustrating the relationships between each variable is presented in Table 2.

Direct or indirect effects (via sleep problems) of bedtime routines towards the child’s well-being

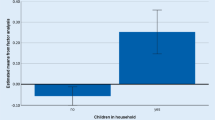

The results of the mediation analysis are shown in Fig. 1. Regression analysis with BTR-Index(S) as the explanatory variable and SDQ_TDS as the explained variable revealed no significant regression coefficient (β = −0.063, p = 0.094). Similarly, regression analysis with BTR-Index(S) as the explanatory variable and CSHQ_TSD as the explained variable also revealed no significant regression coefficient (β = −0.013, p = 0.736). Moreover, multiple regression analysis was performed with BTR-Index(S) and CSHQ_TSD as explanatory variables and SDQ_TDS as the explained variable. The analysis indicated no significant partial regression coefficient for BTR-Index(S) (β = −0.059, p = 0.097), while a significant positive partial regression coefficient for CSHQ_TSD was observed (β = 0.354, p < 0.001). Sobel’s test was performed to confirm the indirect effect of BTR-Index(S) on SDQ_TDS via CSHQ_TSD. The results indicated no significant indirect effects (Z = −0.337, p = 0.736).

Exploratory analyses of the bedtime routines related to the child’s sleep health and well-being

The results of multiple regression analysis with CSHQ_TSD as the explained variable revealed a significant positive partial regression coefficient (β = 0.228, p = 0.006) for BTR-Index item 3, “Reading/sharing a story before bed,” and a significant negative partial regression coefficient (β = −0.222, p = 0.011) for item 5, “Avoiding use of electronic devices before bed” (Table 3, model 1). The entire regression equation was significant (F = 3.361, p = 0.003). Also, In the model with family environmental factors added as explanatory variables, a significant positive partial regression coefficient (β = 0.200, p = 0.014) for BTR-Index item 3 and a significant negative partial regression coefficient (β = −0.208, p = 0.015) for item 5 were found (Table 3, model 2).

Conversely, the results of multiple regression analysis with SDQ_TDS as the explained variable confirmed no significant partial regression in either case, and the entire regression equation was also not significant (F = 0.852, p = 0.530) (Table 4, model 1). The same results were confirmed in the model with family environmental factors added as explanatory variables (Table 4, model 2).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of “adaptive” bedtime routines on children’s well-being, both directly and indirectly through sleep health. The results of our study indicate that the level of implementation of “adaptive” bedtime routines was not significantly associated with a child’s well-being, either directly or indirectly. However, we found that sleep health was significantly related to children’s well-being.

Numerous studies have highlighted the close relationship between children’s sleep health and mental, physical, and neurocognitive development, as well as their overall well-being. The instruments utilized in this study, the CSHQ and SDQ, have consistently shown a relationship between sleep health and children’s well-being [22,23,24]. While BTR-Index (S) was not directly related to sleep health, correlation analysis revealed associations with longer sleep duration, earlier sleep onset and end time on weekdays and free days, an earlier midpoint of sleep, and lower social jet lag (the difference in midpoint sleep between weekdays and holidays). BTR-Index(S) serves as an overall indicator of the incorporation of “adaptive” bedtime routines. The widespread adoption of these routines is associated with sleep habits such as increased sleep duration and greater stability in sleep–wake patterns, but not with the level of sleep disturbance. Previous research focusing on the frequency of the implementing bedtime routines has shown a dose-dependent relationship with various positive sleep outcomes, including longer sleep duration, earlier bedtime, shortened sleep onset latency, and fewer nocturnal awaking [2]. The BTR-Index may not fully capture “adaptive” bedtime routines, as it contains only six items. Future studies using other standardized methods of evaluating bedtime routines (e.g. the Bedtime Routine Questionnaire [25]) should be conducted. The mean value of BTR-Index (S) in this study was high at 72.14 (SD = 25.81), indicating widespread adoption of “adaptive” bedtime routines in many Japanese households. This high mean value may have contributed to the observed lack of relationship with CSHQ_TSD and SDQ_TDS, potentially due to a ceiling effect.

In the exploratory analysis, it was found that “reading/sharing a story before bed” and “NOT avoiding use of electronic devices before bed,” were associated with sleep health disturbance. Additionally, none of the bedtime routine items were related to a child’s well-being. A survey conducted in the United States, encompassing infants to school-age children [26], reported varying association between reading before bed and sleep outcomes across different age groups. While bedtime reading was associated with fewer sleep interruptions and longer sleep duration in infants (11 months), no significant associations were observed for toddlers (12–35 months). However, it was linked to longer sleep duration for preschoolers (3–6 years) and school-age children, with the effect diminishing as the age group increased. In contrast to these findings, the present study revealed a negative effect of reading before bed on sleep health. This discrepancy may be attributed to confounding factors. A review of bedtime routines highlighted the importance of considering these confounding factors, such as the content of the reading material and the suppression of other undesirable sleep hygiene habits due to reading, to validate the direct effect of reading before bed on children’s sleep [1]. The finding that reading had a negative effect on sleep health may be attributed to several confounding factors, including the content of the book (e.g., emotionally evocative content), the medium of the book (e.g., an e-book), or the timing of reading. Further investigation is warranted to explore these factors in future studies. Notably, parent–child book sharing is widely believed to contribute to various aspects of child development, including language skills, joint attention, linguistic interaction, theory of mind, and perspective-taking abilities [27]. However, despite these potential benefits, no significant relationship between bedtime reading and child well-being was found in this study. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that this study did not examine parent–child interactions outside of bedtime. Therefore, further research is needed to evaluate and adaptive communication through daytime activities such as reading books.

The nighttime use of electronic devices is believed to negatively affect a child’s sleep through various mechanisms, including sleep time deprivation, increased wakefulness due to media contents, and disruption of circadian rhythms by the device’s light. A systematic review of studies involving children and adolescents reported that nighttime device use was associated with insufficient sleep duration, poor sleep quality, and excessive daytime sleepiness [28]. These findings suggest that caregivers’ efforts to limit electronic device use at night may help protect sleep health.

Considering these findings, it is suggested that avoiding stimuli that promote wakefulness in children (which may include certain types of reading before bed) during the night could contribute to stabilizing their sleep health. Moreover, the absence of a relationship between bedtime routines and well-being suggests that factors related to the context in which bedtime routines are implemented and the conditions of daily interactions between parents and children may act as confounding variables. Therefore, further examination is warranted.

The limitations of this study are summarized in the following three points.

First, it is important to note that this is a cross-sectional study. In future research, it will be necessary to conduct longitudinal studies to further examine the effects of “adaptive” bedtime routines on a child’s health and well-being among the Japanese population.

Second, the evaluation of bedtime routines in this study was based on the BTR-Index, which was developed using the Delphi process for professionals in the United Kingdom. In the future, it is essential to identify and examine “adaptive” bedtime routines that are specific to Japan’s unique sleep culture (i.e., co-sleeping and bedroom sharing). Moreover, the ceiling effect observed in the BTR-Index among the study participants suggests that there may be limitations in capturing inter-family difference fully.

Third, further adjustment for confounding variables is needed. Specifically, daytime interactions, the duration and timing of bedtime routines, and interactions with the child’s personality were not examined in this study, despite their potential impact on a child’s well-being. Further studies should consider these variables and incorporate them into the analysis.

References

Mindell JA, Williamson AA. Benefits of a bedtime routine in young children: sleep, development, and beyond. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;40:93–108.

Mindell JA, Li AM, Sadeh A, et al. Bedtime routines for young children: a dose-dependent association with sleep outcomes. Sleep. 2015;38(5):717–22.

Boyce WT, Jensen EW, James SA, Peacock JL. The family routines inventory: theoretical origins. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17(4):193–200.

Dickstein S. Family routines and rituals–the importance of family functioning: comment on the special section. J Fam Psychol. 2002;16(4):441–4.

Kitsaras G, Goodwin M, Allan J, Pretty IA. Defining and measuring bedtime routines in families with young children-a DELPHI process for reaching wider consensus. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0247490.

Morgenthaler TI, Owens J, Alessi C, et al. Practice parameters for behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29(10):1277–81.

Astill RG, Van der Heijden KB, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Van Someren EJ. Sleep, cognition, and behavioral problems in school-age children: a century of research meta-analyzed. Psychol Bull. 2012;138(6):1109–38.

Matricciani L, Paquet C, Galland B, et al. Children’s sleep and health: a meta-review. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;46:136–50.

Goodman R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(5):581–6.

Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M. The children’s sleep habits questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep. 2000;23(8):1043–51.

Doi Y, Oka Y, Horiuchi S, et al. The japanese version of children’s sleep habits questionnaire (CSHQ-J) (In Japanese). Jpn J Sleep Med. 2007;2(1):83–8.

Fritz MS, Mackinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(3):233–9.

Ghotbi N, Pilz LK, Winnebeck EC, Vetter C, et al. The µMCTQ: an ultra-short version of the munich chronotype questionnaire. J Biol Rhythms. 2020;35(1):98–110.

Korman M, Tkachev V, Reis C, et al. COVID-19-mandated social restrictions unveil the impact of social time pressure on sleep and body clock. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):22225.

Roenneberg T, Wirz-Justice A, Merrow M. Life between clocks: daily temporal patterns of human chronotypes. J Biol Rhythms. 2003;18(1):80–90.

Wittmann M, Dinich J, Merrow M, Roenneberg T. Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23(1–2):497–509.

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–82.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.2022. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 18 May 2024

Revelle W. psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. R package version 2.3.9, 2023. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych. Accessed 18 May 2024

Bliese P. multilevel: Multilevel Functions. R package version 2.7, 2022. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=multilevel. Accessed 18 May 2024

Fox J, Weisberg S. car: Companion to Applied Regression. R package version 3.1–2, 2019. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=car. Accessed 18 May 2024

Horiuchi F, Kawabe K, Oka Y, et al. Mental health and sleep habits/problems in children aged 3–4 years: a population study. Biopsychosoc Med. 2021;15(1):10.

Ricci C, Poulain T, Keil J, et al. Association of sleep quality, media use and book reading with behavioral problems in early childhood the Ulm SPATZ Health Study. Sleep Adv. 2022; 3(1):zpac020.

Matsuoka M, Matsuishi T, Nagamitsu S, et al. Sleep disturbance has the largest impact on children’s behavior and emotions. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:1034057.

Henderson JA, Jordan SS. Development and preliminary evaluation of the bedtime routines questionnaire. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32:271–80.

Mindell JA, Meltzer LJ, Carskadon MA, Chervin RD. Developmental aspects of sleep hygiene: findings from the 2004 national sleep foundation sleep in America poll. Sleep Med. 2009;10(7):771–9.

Zuckerman B, Elansary M, Needlman R. Book sharing: in-home strategy to advance early child development globally. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182033.

Carter B, Rees P, Hale L, et al. Association between portable screen-based media device access or use and sleep outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1202–8.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 20H01659 and 23H00952.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Sleep Research Institute, Edogawa University, to which RY belongs, receives research funding from PARAMOUNT BED CO.

Ethical approval

This study was permitted by the Research Ethics Committee of Edogawa University prior to data collection (permission number: R04-014A).

Informed consent

All participants gave their consent to participate in the survey of this study.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

Human Participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamamoto, R., Hara, S. The relationships between bedtime routines and preschooler’s sleep health and well-being: a cross-sectional survey in Japan. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 22, 471–479 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-024-00530-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-024-00530-3