Abstract

A cross-sectional survey was conducted to simultaneously evaluate sleep quality, duration, and phase in school-aged children and correlations between each dimension of sleep and daytime sleepiness were comprehensively examined. A cross-sectional survey was conducted with school-aged children enrolled in four public elementary schools in Joetsu city, Niigata prefecture in Japan (n = 1683). Among the collected responses (n = 1290), 1134 valid responses (547 boys and 587 girls) were analyzed (valid response rate was 87.90%). Data on daytime sleepiness, sleep quality (problems in sleeping at night), sleep duration (the average sleeping time during a week), and sleep phase (sleep timing: bedtime and rising time on weekdays, and sleep regularity: differences in bedtime and rising time between on weekdays and weekends) were collected. The results of multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that the following dimensions were significantly correlated with daytime sleepiness: the decline in sleep quality [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 2.62, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.71–4.00], bedtime after 21:30 on weekdays (AOR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.15–2.18), bedtime delay on weekends, compared to weekdays (AOR = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.27–2.41), and bedtime advance on weekends, compared to weekdays (AOR = 3.33, 95% CI = 1.78–6.20). Sleep dimensions that significantly affected daytime sleepiness in school-aged children are sleep quality, bedtime-timing, and regularity of bedtime. It is important to detect problems in night sleep and establish treatments, as well as to provide support for early bedding on weekdays and for a regular bedtime both on weekdays and on weekends to prevent daytime sleepiness in school-aged children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Daytime sleepiness in school-aged children is regarded as an important problem from the perspective of school health because it causes various problems in life [1]. It has been reported that daytime sleepiness deteriorates mental and physical health [2], as well as attention [3] and learning capacity [4], which have negative effects on school performance [5].

It is considered that daytime sleepiness in school-aged children might be caused by problems in the following dimensions: sleep quality, duration, and phase. First, sleep quality is a dimension related to starting and continuing sleep as well as the degree of disorders in sleep structure. Problems in night sleep leading to daytime sleepiness include insomnia disorders, restless legs syndrome, and sleep apnea among others [6]. A longitudinal study conducted with adolescents reported that a decline in sleep quality would cause daytime sleepiness [7]. Second, sleep duration is a dimension related to the degree of lack of sleep. Accumulation of a sleep debt excessively increases sleep pressure and causes daytime sleepiness. In recent years, it has been advocated that recommended sleep duration for school-aged children is 9–11 h [8]. However, there is a report that the average sleeping hours of Japanese school-aged children is 7 h and 36 min [9]. Moreover, a survey conducted with junior high school students has reported sleep time less than the recommended sleep duration which causes daytime sleepiness [10]. The above results suggest that many school-aged children in Japan have daytime sleepiness, because of the accumulated sleep debt. Third, sleep phase is a dimension related to the degree of disorders in the sleep-wake cycle. It is divided into two dimensions; sleep timing and sleep regularity. The former is involved in bedtime and rising time on weekdays and the latter is involved in differences in bedtime and rising time between weekdays and weekends [11]. It has been reported that late bedtime and late rising time on weekdays disturb the sleep–wake cycle, which causes daytime sleepiness [12]. Moreover, there is a report that bedtime delay and rising-time delay on weekends, compared to weekdays, increase daytime sleepiness [13].

Previous studies have examined correlations between three dimensions of sleep and daytime sleepiness. Based on their findings, public health activities for ensuring adequate sleep among school-aged children have been implemented, based on the perspective of each dimension [14]. However, correlations among the three dimensions and correlations between each dimension and daytime sleepiness, by considering the inter-dimensional correlations, have not been undertaken [15]. It has been indicated that problems in three dimensions might be correlated with various problems [15]. For example, reduction in sleep duration and bedtime delay might have been caused by sleep habits chosen by children themselves. On the other hand, these sleep habits might have been produced by problems in night sleep. Therefore, it would be necessary to examine the effects of each dimension on daytime sleepiness, with considering correlations among the three dimensions, when providing appropriate support for preventing daytime sleepiness in school-aged children.

In this study, data collected through a cross-sectional survey using the Child and Adolescent Sleep Checklist (CASC) [16], by which sleep quality, duration, and phase are simultaneously evaluated, were analyzed. Furthermore, correlations between each dimension and daytime sleepiness were comprehensively examined.

Materials and methods

Participants

A cross-sectional survey was conducted with school-aged children enrolled in four public elementary schools in the urban area of Joetsu city, Niigata prefecture, Japan. The total number of the children enrolled in the schools was 1683, excluding those enrolled in special needs classes. The extraction ratio was 25.73% of all the school-aged children living in the urban area of Joetsu city. Among the collected responses (N = 1290), those with missing values regarding the grade, gender, or three items related to daytime sleepiness in CASC [16] were excluded from the study. Finally, 1134 responses (547 boys and 587 girls) were analyzed. The valid response rate was 87.90%.

Survey procedures

This survey was implemented as a part of the research project of Joetsu University of Education, “Descriptive and epidemiological studies on correlations between sleep habits of school-aged children and their families-Establishment of sleep health education at elementary school (II)-” (principal investigator: Ryuichiro Yamamoto). From September to October in 2015, written and oral explanations about research purposes and ethical consideration were provided to the principals of the elementary schools. The survey was conducted at schools that gave consent to the study. Class teachers distributed envelops enclosing an explanation letter, a questionnaire, and a reply envelope to students. Teachers told students to give the envelope to their parents when returning home. Students opened the envelope with their parents at home, and read explanations about study purposes and ethical confirmation. When they agreed to participate in the survey, they responded to the questionnaire. After responding, they put the questionnaire in the envelope and sealed it. Students brought it to school and submitted it to the class teacher. The questionnaires were directly collected by researchers.

Materials

There were two types of questionnaires: a questionnaire for parents and children. The contents of the questionnaire for parents included the consent form, specification of the respondent, items on the child’s grade, age, gender, height, weight, bedding, and bedtime lighting, items on family members’ bedtime and rising time on weekdays and weekends, total sleep time, and sleep-related problems, as well as CASC (evaluation of children’s sleep habits and sleep problems by parents). The contents of the questionnaire for children included CASC (self-evaluation of sleep habits and sleep problems). In this study, parents’ responses about children’s grade and gender as well as children’s responses to CASC were used for analysis.

CASC is a questionnaire regarding sleep habits and sleep problems, responded by children themselves. Items related to sleep habits consist of bedtime and rising time on weekdays and weekends as well as sleep duration. Items for assessing sleep problems are composed of four components below, including 24 items; the first component: bedtime problems, the second component: sleep breathing and unstable sleep, the third component: parasomnia and sleep movement, and the fourth component: daytime problems. These items are evaluated using the four-point Likert scale; “always (5–7 days/week),” “sometimes (2–4 days/week),” “occasionally (1 day/week),” and “never.”

Definition of variables

Table 1 shows the operational definition of sleep quality, duration, phase, and daytime sleepiness.

Statistical analysis

Aiming to describe participants’ sleep characteristics, frequency distribution tables were developed for sleep quality, duration, phase, and daytime sleepiness, depending on the grade and gender. Moreover, a residual analysis was conducted for examining whether there are differences in three dimensions of sleep and the frequency of sleepiness among grades and between genders. Aiming to examine correlations among grade, gender, and three dimensions of sleep, Cramér’s V among variables was calculated.

Furthermore, logistic regression analysis was conducted with grade, gender, and three dimensions of sleep as explanatory variables and daytime sleepiness as an explained variable. First, crude odds ratio (OR) [95% confidence interval (CI)] of each explanatory variable was calculated through univariate logistic regression analysis. Next, adjusted OR (95% CI) of each explanatory variable was calculated using multivariate logistic regression analysis (backward elimination method: excluded when p < 0.1). We set the level of significance at p < 0.05. IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM corp., Armonk, NY) was used for analyses.

Ethical consideration

Voluntariness of one’s response to a questionnaire and protection of personal information were explained to parents and children by an explanatory document. Consent to participation in the survey was confirmed by filling in the consent form, included in the questionnaire. This study was permitted by the Ethics Committee of Joetsu University of Education (Permission number: 56).

Results

Characteristics of three dimensions of sleep and daytime sleepiness in participants

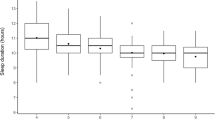

Table 2 shows frequency distribution of three dimensions of sleep and daytime sleepiness. The results of residual analysis indicated significant differences in the expected frequency and observed frequency between genders, in (1) “advanced” in regularity of bedtime, (2) “delay,” “regular,” and “advance” in regularity of rising time, in the data of the whole participants. Regarding boys, significant differences in the expected frequency and observed frequency were indicated among grades, in (1) “no” and “yes” in daytime sleepiness, (2) “<9 h,” “9–11 h,” and “>11h” in sleep duration, (3) “before 21:30” and “after 21:30” in bedtime-timing, and (4) “before 6:30” and “after 6:30” in rising time-timing. Regarding girls, significant differences in the expected frequency and observed frequency were indicated among grades, in (1) “no” and “yes” in daytime sleepiness, (2) “<9h” and “9-11h” in sleep duration, (3) “before 21:30” and “after 21:30” in bedtime-timing, (4) “before 6:30” and “after 6:30” in rising time-timing, and (5) “delay,” “regular,” and “advance” in bedtime-timing.

Correlations among grade, gender, and three dimensions of sleep

Table 3 shows correlations among grade, gender, and three dimensions of sleep. Cramér’s V among variables was calculated and significant correlations were indicated as follows: (1) between sleep quality and rising time-timing as well as regularity of bedtime, (2) between sleep duration and bedtime-timing, regularity of bedtime, as well as grade, (3) between bedtime-timing and rising time-timing, regularity of bedtime, regularity of rising time, as well as grade, (4) between rising time-timing and regularity of bedtime, regularity of rising time, as well as grade, (5) between regularity of bedtime and regularity of rising time, as well as between regularity of rising time and gender.

Correlations between grade, gender, as well as three dimensions of sleep and daytime sleepiness through logistic regression analysis

Table 4 shows the results of the final step of univariate logistic regression analysis and multivariate logistic regression analysis (backward elimination method). The results of univariate logistic regression analysis indicated that grade, sleep quality, sleep duration, bedtime-timing, rising time-timing, regularity of bedtime, and regularity of rising time were significantly correlated with daytime sleepiness. Moreover, the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that grade, sleep quality, bedtime-timing, and regularity of bedtime were significantly correlated with daytime sleepiness. Sleep duration and regularity of rising time were excluded from the model.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to simultaneously evaluate sleep quality, duration, and phase in school-aged children, and comprehensively examine correlations between those dimensions of sleep and daytime sleepiness. Previous studies had been examining correlations between daytime sleepiness and three dimensions of sleep from the respective perspective. As far as we know, this is the first report that simultaneously evaluated these three dimensions of sleep and indicated the differences in their correlations with daytime sleepiness. The results of this study have indicated that sleep quality, bedtime-timing, and regularity of bedtime significantly affect daytime sleepiness.

Sleep quality

It was indicated that children with night sleep problems had daytime sleepiness more than those without such problems. It has been reported that a certain number of children have night sleep problems such as insomnia disorders [19], restless legs syndrome [20], and sleep apnea [21] among others. In previous public health activities for ensuring adequate sleep among school-aged children, the main problem of daytime sleepiness was considered to have been caused by life habits selected by children themselves, i.e., “do not sleep.” Therefore, in the activities, approaches to facilitate behavioral changes were considered important. However, there might be children that “want to sleep but cannot,” or “are sleeping but cannot have a good quality sleep.” For example, when children with insomnia try to go to bed early, the association between sleep environment and awakening gets stronger, leading to a decline in sleep quality and sleep efficiency [15]. It is considered important to construct systems for detecting night sleep problems in the early stage and providing early treatment, for supporting school-aged children with daytime sleepiness.

Bedtime-timing

School-aged children that go to bed late on weekdays tended to show daytime sleepiness more often than those that go to bed early. In the previous studies, a correlation between bedtime and daytime sleepiness has been indicated [12]. On weekdays, school-aged children get up at a fixed time to go to school. When weekday bedtime is delayed, a sleep debt is accumulated, which would cause daytime sleepiness. However, the results of this study did not show a correlation between reduction of sleep duration and daytime sleepiness. This might be caused by the fact that 92.42% of the participants secured “recommended” or “maybe appropriate” sleep duration suggested by the National Sleep Foundation. The percentage of those that did not reach “recommended” or “maybe appropriate” sleep duration was only 1.85%. That is, most of the participants secured sufficient sleep duration, and even if it slightly changed, daytime sleepiness was not affected. From the perspective of countermeasures against daytime sleepiness, it would be important to prevent the sleep-wake cycle from being disturbed, by supporting early bedtime and consistent bedtime on weekdays and on weekends, not just prolonging sleep duration.

Regularity of bedtime

School-aged children that go to bed later or earlier on weekends, compared to on weekdays, showed daytime sleepiness more often than those go to bed at a fixed time both on weekdays and on weekends. By contrast, there were no correlations between daytime sleepiness and a delay or advance in rising time on weekends, compared to weekdays. It would be important to provide support for school-aged children, so that they can keep consistent bedtime on weekdays and weekends, for preventing daytime sleepiness.

Bedtime delay on weekends, compared to weekdays

Bedtime delay on weekends disturbs a sleep-wake cycle that was established on weekdays, which would cause a delay in the phase of melatonin secretion and melatonin suppression. The phase delay of melatonin secretion is explained based on the phase response curve (PRC). According to PRC, when exposed to light in the morning for the biological clock, melatonin secretion phase advances. Contrarily, when exposed to light at night for the biological clock, melatonin secretion phase delays. It has been pointed out that in the youth, melatonin secretion phase delay might be dominant over advance [22]. The pupil size of school-aged children is large [23], and the transmission rate of a short wavelength of light in the crystal lens is high [24]. Therefore, melatonin suppression caused by light exposure more easily occurs, compared to adults [25]. School-aged children that go to bed late on weekends have more opportunities for light exposure at night for the biological clock, which would lead to melatonin secretion phase delay and melatonin suppression. It produces a temporary lack of sleep caused by a difficulty in falling asleep on weekends and disturbance of a sleep-wake cycle, which is maintained on weekdays, leading to daytime sleepiness [26]. In the future, effects of bedtime delay on weekends on melatonin secretion phase and melatonin suppression in school-aged children should be examined.

Bedtime advance, compared to weekdays

As far as we know, there is no study that examined the correlation between bedtime advance on weekends and daytime sleepiness, as it might also disturb a sleep-wake cycle. In addition, bedtime advance on weekends might occur for compensating for daytime sleepiness. In the future, correlations between bedtime advance on weekends and daytime sleepiness should be minutely examined through a longitudinal survey.

Developmental changes in sleep habits and daytime sleepiness

Bedtime delay, rising time delay, short sleep duration, and much daytime sleepiness were confirmed in upper-grade children. It has been reported that bedtime delay and reduction of sleep duration are considerably observed in school-aged children that are approaching puberty [27]. These changes in sleep habits are supposed to be caused by changes in sleep environment and psychological/physical changes related to secondary sexual characteristics. Children in China, located in East Asia like Japan, often sleep with their parents from infancy to mid-childhood [28]. However, school-aged children in late childhood start to sleep alone [28]. Consequently, as grade in school advanced, sleep environment and bedtime activity can change. For example, it has been reported that the rate of browsing internet before bedtime increases with advancing grades of school-aged children in Japan [29]. Furthermore, children who use internet tend to go to bed later than the others who do not use it [29]. Moreover, children that start to show secondary sexual characteristics have physiological changes such as delayed timing of melatonin secretion [30] and a decline in sleep pressure regulated by homeostasis [31]. An increase in daytime sleepiness in children of this age might be caused by two factors: (1) children do not sleep because they do not want to sleep, owing to changes in sleep environment and (2) they cannot sleep even if they want to sleep early, because of physiological changes. Recently, it has been indicated that it might be effective to delay school start time for securing “good sleep” for school-aged children [32]. In Japan, however, elementary school start time (mostly 8:30) is already relatively late, compared to foreign countries, and there are some problems in delaying school start time in the present educational system [15]. In the future, correlations between daytime sleepiness and changes in sleep environment as well as physiological changes in children in the period of showing secondary sexual characteristics should be minutely examined, and countermeasures should be discussed.

Limitations and future directions

The limitations of this study are as follows: (1) There was a bias in sampling. This study was conducted in a specific area. There might be differences in sleep habits between children living in urban areas and those living in rural areas. For example, usually, it takes a longer time to go to school for children living in rural areas, compared to those in urban areas. Therefore, they need to wake up earlier. In the future, possibilities of generalization of the results of this study should be examined, with expanding the target area to a national scale, including urban and rural areas. (2) Data used in this study are based on children’s self-report, collected through a questionnaire. Rising time on weekdays is relatively fixed by school start time and commuting time in school-aged children, and self-report would have reliability. However, there is intra-individual variation in how to spend weekends, and comprehensive evaluation is difficult. In the future, data should be collected using objective sleep assessment methods such as actigraph and compared with the data of this study. (3) The research design of this study was cross-sectional. As described above, earlier bedtime on weekends and the day before weekends were correlated with daytime sleepiness. However, the direction of the causal relationship is not clear. Bedtime delay on weekends might occur for compensating for daytime sleepiness. In the future, a longitudinal study should be conducted.

References

Fallone G, Owens JA, Deane J. Sleepiness in children and adolescents: clinical implications. Sleep Med. 2002;6:287–306.

Shochat T, Cohen-Zion M, Tzischinsky O. Functional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:75–87.

Perez -Lloret S, Videla AJ, Richaudeau A, Vigo D, Rossi M, Cardinali DP, Perez-Chada D. A multiple-step pathway connecting short sleep duration to daytime somnolence, reduced attention, and poor academic performance: an exploratory cross-sectional study in teenagers. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:469–73.

Curcio G, Ferrara M, Gennaro LD. Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:323–37.

Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkhof GA, Bögels SM. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:179–89.

Slater G, Steier J. Excessive daytime sleepiness in sleep disorders. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4:608–16.

Yamamoto R, Kaneita Y, Harano S, Yokoyama E, Tamaki T, Munezawa T, Suzuki H, Ohtsu T, Aritake S. New onset and natural remission of excessive daytime sleepiness and its correlates among high-school students. Sleep Biol Rhythm. 2011;9:117–26.

Hirshkowitsz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, Hazen N, Herman J, Hillgard PJA, Katz ES, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Neubauer DN, O’Donnel AE, Ohayon M, Peever J, Rawding R, Sachdeva RS, Setters B, Vitiello MV, Ware JC. National sleep foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final report. Sleep Health. 2015;1:233–43.

NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute. Report of the survey on living hours of Japanese people, 2010 (in Japanese). Nihon Housou Kyoukai (Tokyo). 2010. https://www.nhk.or.jp/bunken/research/yoron/pdf/20160217_1.pdf. Accessed 19 Oct 2017.

Gaina A, Sekine M, Hamanishi S, Chen X, Wang H, Yamagami T, Kagamimori S. Daytime sleepiness and associated factors in japanese school children. J Pediatr. 2007;151:518–22.

Matsumoto Y, Uchimura N, Ishida T, Toyomasu K, Kushino N, Mori M, Morimatsu Y, Hoshiko M, Ishitake T. Reliability and validity of the 3dimensional sleep scale (3DSS)-day worker version-in assessing sleep phase, quality, and quantity (in Japanese). J Occup Health (Tokyo). 2014;56:128–40.

Gradisar M, Gardner G, Dohnt H. Recent worldwide sleep patterns and problems during adolescence: a review and meta-analysis of age, region, and sleep. Sleep Med. 2011;12:110–8.

Yang C, Spielman AJ. The effect of delayed weekend sleep pattern on sleep and morning function. Psychol Health. 2001;16:715–25.

Blunden SL, Chapman J, Rigney GA. Are sleep education programs successful? The case for improved and consistent research efforts. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16:355–70.

Yamamoto R. Public health activities for ensuring adequate sleep among school-age children: current status and future directions. Sleep Biol Rhythm. 2016;14:241–7.

Oka Y, Horiuchi H, Tanigawa T, Suzuki S, Kondo T, Sakurai S, Saito I, Tanimukai S, Ueno S, Inoue Y. Development of a new sleep screening questionnaire: child and adolescent sleep checklist (CASC) (in Japanese). Jpn J Sleep Med (Tokyo). 2009;3:404–8.

Olds TS, Maher CA, Matricciani L. Sleep duration or bedtime? Exploring the relationship between sleep habits and weight status and activity patterns. Sleep. 2011;34:1299–307.

Miller AL, Kaciroti N, Lebourgeois MK, Chen YP, Sturza J, Lumeng JC. Sleep timing moderates the concourrent sleep duration-body mass index association in low-income preschool-age children. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:207–13.

Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M, Nobile C. Sleep habits and sleep disturbance in elementary school-aged children. Dev Behav Pediatr. 2000;21:27–34.

Picchietti D, Allen RP, Walters AS, Davidson JE, Myers A, Ferini-Strambi L. Restless legs syndrome: prevalence and impact in children and adolescents-the Peds REST study. Pediatr. 2007;120:253–66.

Kitamura T, Miyazaki S, Kadotani H, Suzuki H, Kanemura T, Komada I, Nishikawa M, Kobayashi R. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in Japanese elementary school children aged 6–8 years. Sleep Breath. 2014;18:359–66.

Carskadon MA, Wolfson AR, Acebo C, Tzoschinsky O, Seifer R. Adolescent sleep patterns, circadian timing, and sleepiness at a transition to early school days. Sleep. 1998;21:871–81.

Winn B, Whitaker D, Elliott DB, Phillips NJ. Factors affecting light-adapted pupil size in normal human subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:1132–7.

Boettner EA, Wolter JR. Transmission of the ocular media. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1962;1:776–83.

Higuchi S, Nagafuchi Y, Lee S, Harada T. Influence of light at night on melatonin suppression in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3298–303.

Taylor A, Wright HR, Lack LC. Sleeping-in on the weekend delays circadian phase and increases sleepiness the following week. Sleep Biol Rhythm. 2008;6:172–9.

Carskadon MA, Vieira C, Acebo C. Association between puberty and delayed phase preference. Sleep. 1993;16:258–62.

Li S, Jin X, Yan C, Wu S, Jiang F, Shen X. Bed- and room-sharing in Chinese school-aged children: prevalence and association with sleep behaviors. Sleep Med. 2008;9:555–63.

Oka Y, Suzuki S, Inoue Y. Bedtime activities, sleep environment, and sleep/wake patterns of Japanese elementary school children. Behav Sleep Med. 2008;6:220–33.

Crowley SJ, Acebo C, Carskadon MA. Sleep, circadian rhythms, and delayed phase in adolescence. Sleep Med. 2007;8:602–12.

Taylor DJ, Jenni OG, Acebo C, Carskadon MA. Sleep tendency during extended wakefulness: insights into adolescent sleep regulation and behavior. J Sleep Res. 2005;14:239–44.

Wheaton AG, Chapman DP, Croft JB. School start times, sleep, behavioral, health, and academic outcomes: a review of the literature. J Sch Health. 2016;86:363–81.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Research Project of Joetsu University of Education (General Research 2014–2015) and JSPS KAKENHI Grant No. JP 16H03247.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was permitted by the Ethics Committee of Joetsu University of Education (Permission number: 56).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hara, S., Yamamoto, R., Maruyama, M. et al. Relationships between daytime sleepiness and sleep quality, duration, and phase among school-aged children: a cross-sectional survey. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 16, 177–185 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-018-0148-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-018-0148-8