Abstract

Adolescence is marked by a unique blend of factors, including adolescents’ exploration of their emerging sexuality and growing engagement with digital media. As adolescents increasingly navigate online spaces, cybergrooming victimization has emerged as a significant concern for the development and protection of young people. Yet, there is a lack of systematic analyses of the current state of research. To this end, the present systematic review aimed to integrate existing quantitative research on prevalence rates, risk factors, and outcomes of cybergrooming victimization, informed by an adaptation of the General Aggression Model. Studies providing self-reported data on cybergrooming victimization of people between the ages of 5 and 21 were included. A total of 34 studies met all inclusion criteria, with most focusing on adolescence. Reported prevalence rates were characterized by strong heterogeneity, which could largely be attributed to the underlying methodology. Overall, the included studies showed that at least one in ten young people experiences cybergrooming victimization. Findings further indicated that various factors, for example, being a girl, being older, engaging in risky behavior, displaying problematic Internet use, reporting lower mental well-being, and experiencing other types of victimization, are positively associated with cybergrooming victimization. However, most studies’ cross-sectional designs did not allow for an evidence-based classification into risk factors, outcomes, and co-occurrences, so findings were embedded in the proposed model based on theoretical considerations. In addition, there is a noted lack of studies that include diverse samples, particularly younger children, LGBTQIA+ youth, and young people with special educational needs. These findings emphasize that cybergrooming victimization is a prevalent phenomenon among young people that requires prevention and victim support addressing multiple domains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The diversity of easily accessible online platforms and the ubiquity of the Internet in young people’s lives expose them to various online risks. This includes cybergrooming as a form of sexual victimization that may adversely impact young people’s well-being and psychosocial development. Although research syntheses on various aspects of cybergrooming exist (e.g., Broome et al., 2018; Whittle et al., 2013a), reviews specifically on prevalence rates and risk factors of cybergrooming victimization were narrative rather than systematic, while reviews on outcomes have not been conducted at all. Furthermore, no theoretical model has yet been applied to the complex of risk factors, cybergrooming victimization, and outcomes. The present study addresses these desiderata by systematically reviewing prevalence rates, risk factors, and outcomes of cybergrooming victimization embedded in an adaptation of the General Aggression Model (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Kowalski et al., 2014).

Definition and Relevance of Cybergrooming

Information and communication technologies are deeply ingrained in the daily lives of young people. More specifically, social media networks, online games, chat platforms, and e-learning platforms allow young people to foster social contacts with peers, access information, and engage in learning and entertainment activities. However, alongside these benefits, the Internet also poses potential risks for young people. For instance, they may experience sexual victimization online (Bozzola et al., 2022; Livingstone & Smith, 2014), facilitated by the anonymity, accessibility, and affordability characterizing information and communication technologies (Cooper, 1998). In this context, cybergrooming has received increasing attention in research in recent years. Although there is some variation in the applied definitions of cybergrooming, a common overlap of core aspects of the phenomenon can be observed, namely (1) minors are targeted, (2) perpetrators use information and communication technologies to establish contact, (3) the process serves sexual purposes, and (4) some kind of relationship between perpetrator and victim is built (e.g., Kloess et al., 2014; Wachs, 2014; Webster et al., 2012; Whittle et al., 2013a). Thus, cybergrooming can be defined as a process through which a person, usually an adult, establishes a sexually exploitative relationship with a minor using information and communication technologies (Webster et al., 2012; Whittle et al., 2013a). Importantly, cybergrooming is not to be equated with sexual abuse but instead refers to a psychologically manipulative process that targets and may result in online and/or offline sexual abuse (Pasca et al., 2022).

It can be argued that adolescence is a particularly vulnerable phase for cybergrooming victimization. First, in late childhood and adolescence, in particular, online behavior changes as the use of apps and platforms to interact with others, such as WhatsApp, Instagram, and Snapchat, becomes more pronounced (e.g., Feierabend et al., 2022, 2023; Shi et al., 2024), providing perpetrators with more opportunities to connect. Second, adolescents explore their sexuality as a natural process (Tolman & McClelland, 2011), involving the development of a sexual identity, search for guidance, and onset of sexual activities. During this process, adolescents use information and communication technologies as a means of exploring and expressing their sexuality (e.g., Eleuteri et al., 2017; Lemke & Rogers, 2020). Thus, adolescents are increasingly interested in sexual matters in the offline and online world, which might make them more vulnerable to sexual advances from cybergroomers. Therefore, increased social Internet use and sexual curiosity may enhance adolescents’ exposure risk to cybergrooming. Third, it was pointed out that hebephilia, i.e., a sexual preference for adolescents, may be more widespread among online sexual offenders than pedophilia, i.e., a sexual preference for children (e.g., Wachs, 2014; Wolak et al., 2008). However, in striving for a holistic overview of cybergrooming victimization among minors, this review will also include research on younger children.

Perpetrators benefit from the wide range of tools and opportunities to approach young people online, given that various platforms and apps are used daily by most of the youth (e.g., Külling et al., 2022; Landesanstalt für Medien NRW, 2022). Many diverse platforms have emerged in recent years that facilitate perpetrators initiating and maintaining the cybergrooming process. For example, there are platforms and apps without proper age verification strategies that allow users to connect anonymously with strangers (e.g., Omegle, Kik), giving perpetrators easy and subtle access to many potential victims. With mainly image-based apps (e.g., Snapchat), perpetrators can contact a pool of potential victims directly with (pornographic) image and video material, and the self-deletion function of pictures and videos makes it more difficult to secure evidence for perpetration. It might further reduce young people’s inhibitions to send pornographic material themselves, even though taking screenshots is still possible. Perpetrators can also misuse online games (e.g., Roblox, Fortnite), as they offer them the opportunity to approach young players under the pretext of a shared interest in the game and facilitate establishing a relationship by providing virtual game-related gifts. While the risk of exposure to cybergrooming can be reduced for some platforms, for example, by activating a parental control function (e.g., YouTube, Meta), there are no or only a few such options for other platforms (e.g., Omegle, Pinterest).

In terms of prevalence, an overall increase in cybergrooming activities has been observed recently (e.g., Europol, 2021; Landesanstalt für Medien NRW, 2022). For instance, studies have revealed that the number of young people who have been promised rewards in exchange for photos or videos of themselves has increased (2021: 14.2%, 2022: 19.5%; Landesanstalt für Medien NRW, 2022), as well as the number of young people who have been approached online by strangers with unwanted sexual solicitations (2014: 19%, 2018: 30%, 2022: 47%; Külling et al., 2022). However, due to heterogeneity in the conceptualization of cybergrooming, measurement instruments, and cut-off criteria (Machimbarrena et al., 2018), estimated prevalence rates may vary between studies. A systematic analysis of prevalence rates aims to provide a reliable estimate of the extent of cybergrooming victimization. This is particularly relevant in terms of public health policy as it allows for an estimate of the threat level and the urgency of prevention efforts. Beyond that, profound knowledge of risk factors and outcomes of victimization is necessary to identify vulnerable groups, develop and implement appropriate prevention efforts, and provide the best support for victims to minimize harmful consequences for their well-being and psychological development.

Cybergrooming Victimization Through the Lens of the General Aggression Model

The General Aggression Model, originally introduced as a framework for understanding human aggression (Anderson & Bushman, 2002), has been effectively extended to various forms of cyber aggression, including cyberbullying (Kokkinos & Antoniadou, 2019; Kowalski et al., 2014). Notably, this model has been adapted to address cyberbullying victimization as well, where it links risk factors, experiences of victimization, and their consequent outcomes (Kowalski et al., 2014). This modified version of the General Aggression Model provides a comprehensive perspective on the dynamics involved in cyberbullying, illustrating how different elements interact to influence both the behavior of aggressors and the experiences of victims. Following this line of research, the modified version of the General Aggression Model is adapted for this review to cybergrooming victimization (see Fig. 1). This model comprises four core elements connected to victimization: (1) person and situational inputs as risk factors for victimization, (2) internal states created by victimization through cognitive, affective, and arousal routes, (3) proximal processes influenced by internal states, involving appraisal of the situation and subsequent decision-making, and (4) distal outcomes as longer-term adverse outcomes of victimization.

Inputs

The model postulates that person and situational risk factors represent vulnerabilities and exposure risks for victimization, referred to as inputs. Person factors include all individual characteristics (e.g., personality, behavioral scripts), while situational factors refer to all environmental characteristics (e.g., parental education, access to information and communication technologies). Consistent with the proposed model, a variety of potential risk factors for cybergrooming victimization from different domains were identified based on interviews with young people (Whittle et al., 2014), which can be classified into person (e.g., loneliness, boredom in the home environment, school behavioral problems, excessive time spent online) and situational factors (e.g., separated parents, being bullied).

Cybergrooming Victimization

In the proposed model, the term cybergrooming victimization involves the actual grooming process and sexual abuse. Although sexual abuse is considered a proximal outcome of the cybergrooming process, both cannot be precisely distinguished as separate, successive stages. For example, pornographic material sent by the victim, which is considered an act of sexual abuse, can be misused by perpetrators for the further grooming process (e.g., via flattery, blackmail). Further, from a psychometric point of view, the exchange of pornographic material is a component of most questionnaires for assessing cybergrooming victimization, e.g., the Questionnaire for Online Sexual Solicitation and Interaction of Minors with Adults (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2018a). The term cybergrooming victimization, as used in this review, therefore encompasses the complex of the cybergrooming process with and without sexual abuse.

Routes and Proximal Processes

The cybergrooming victimization experience creates internal states through cognitive, affective, and arousal routes (e.g., discomfort, affection) leading to an appraisal of the victimization experience (e.g., perception as a threat, interpretation as a relationship) based on which decisions are made (e.g., termination of conversation, offline meeting). This illustrates cybergrooming as a psychologically manipulative process. The perpetrator’s strategies during the grooming process may manipulate the victim’s internal states and appraisal in such a way that they make decisions in favor of the perpetrator’s interests (e.g., continuing the conversation, sending pictures). This may contribute to the continuity of the victimization, which is illustrated by the dashed line added to the model.

Distal Outcomes

Distal outcomes are conceptualized as longer-term adverse outcomes following the victimization experience (e.g., depression, behavioral problems). Thus, a distinction must be made between sexual abuse as a proximal outcome of the cybergrooming process and longer-term adverse outcomes of the victimization depicted as distal outcomes in the model. This review focuses on the latter, i.e., when referring to outcomes, distal outcomes are meant. Interviews with victims of cybergrooming that has led to sexual abuse demonstrated that distal outcomes are conceivable in terms of mental health (e.g., inability to forget the abuse), physical health (e.g., self-harm), social functioning (e.g., difficulties in relationships), and behavioral problems (e.g., aggression) (Whittle et al., 2013b). According to the model, distal outcomes can feed back into person and situational factors as inputs, e.g., relationship difficulties can increase loneliness (Schwartz-Mette et al., 2020). Thus, distal outcomes are detrimental because they impair victims’ well-being and may also increase the risk of revictimization.

Previous Research Syntheses on Cybergrooming

Previous research conducted on cybergrooming yielded several narrative reviews on cybergrooming characteristics (Whittle et al., 2013a), prevalence, grooming process, and perpetrator characteristics (Kloess et al., 2014), risk factors for victimization (Whittle et al., 2013c), prevention efforts (Wurtele & Kenny, 2016), machine learning models for detecting cybergrooming (Borj et al., 2023), as well as broader reviews tapping different aspects of cybergrooming (Choo, 2009; Forni et al., 2020). Scoping or systematic reviews were conducted less frequently, focusing on cybergrooming strategies (Ringenberg et al., 2022) and perpetrator typologies (Broome et al., 2018; Del Castillo et al., 2021). Although there is an existing scoping review on prevalence rates and risk factors relating to cybergrooming (Gandolfi et al., 2021), it is phenomenologically rather broad as the review’s literature search also targeted studies on online sexual victimization and abuse of minors in more general terms. Notably, the authors state that only one study explicitly focusing on cybergrooming was included for prevalence rates. While this review provides valuable insights into prevalence rates and risk factors regarding the broader field of online sexual victimization, a review narrowed down to cybergrooming victimization is still warranted.

In conclusion, there are currently only narrative but no systematic reviews on prevalence rates and risk factors specifically for cybergrooming victimization. However, narrative reviews are inferior to systematic reviews in terms of rigor, transparency, reproducibility, and objectivity to the entire research process, limiting their informative value, reliability, and minimization of bias (Munn et al., 2018). Beyond that, there is not yet a single review on the outcomes of cybergrooming victimization. This is a shortcoming in the current state of literature when aiming for a comprehensive understanding of cybergrooming victimization in the sense of the General Aggression Model.

Current Study

The current state of research on cybergrooming victimization lacks systematic research syntheses on prevalence rates, risk factors, and outcomes informed by a theoretical framework. Therefore, the primary aim of the present systematic review was to provide an overview of the international literature on prevalence rates and, following an adaptation of the General Aggression Model, personal risk factors, situational risk factors, and distal outcomes of cybergrooming victimization among children and adolescents. The secondary objective of this review was to gather available information on moderators and mediators of the relation between cybergrooming victimization and risk factors or outcomes.

Methods

The present review followed the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews (Page et al., 2021) and was preregistered on February 29th, 2024, with OSF Registries (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FHYW7). Please note that the title has been slightly changed and is no longer identical to the pre-registered title.

Search Strategy

The search strategy followed a two-stage process to identify relevant publications. In the first step, the academic databases PubPsych, PsycINFO, PSYNDEX, PubMed, and Web of Science were searched on March 1st, 2024. The following search-string was utilized on titles, abstracts, keywords and/or subject terms: (child* OR youth* OR adolesc* OR pupil* OR student* OR young* OR teenage* OR minor* OR victim*) AND (online groom* OR cybergroom* OR cyber groom* OR online sexual groom* OR Internet groom*). Since German-language publications were also to be included, the search-string was translated into German for PSYNDEX and PubPsych (kind* OR jugend* OR adolesz* OR schüler* OR student* OR jung* OR teenage* OR minderjährig* OR viktim* OR opfer*) AND (online groom* OR cybergroom* OR cyber groom* OR sexuell* online groom* OR Internet groom*).

In the second step, an additional search for relevant publications not identified by database search was carried out based on (a) reference lists of key sources, i.e., publications that were expected to be identified and used to validate the search strategy, (b) publications of key authors, i.e., authors listed at least four times as the first author of publications identified by the database search, and (c) recent publications citing a key source. Reference lists of key sources, titles of key authors’ publications, and titles of publications since 2022 citing a key source were manually scanned on March 10th and 11th, 2024.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Publications were included in the review if (a) they investigated cybergrooming victimization, (b) a self-report measure of cybergrooming victimization with at least one item was employed, (c) participants were asked to report real-life experiences with cybergrooming victimization in the past, (d) the reported cybergrooming incident occurred between the ages of 5 and 21, (e) information on self-reported prevalence rates of cybergrooming victimization or at least one risk factor or outcome was provided, (f) it was a quantitative empirical study, (g) it was available in English or German, and (h) the publication type was appropriate (journal papers, conference papers with full-study-report, monographs, dissertations, public research reports), i.e., bachelor’s or master’s theses were excluded. Publications were further excluded if (a) they focused exclusively on offline sexual child grooming, (b) aspects other than cybergrooming victimization such as perpetrators or police investigative practices were studied, (c) the reported cybergrooming incident did not occur between the ages of 5 and 21, (d) cybergrooming victimization was measured only via third-party report, (e) participants were asked only about a hypothetical cybergrooming victimization situation, (d) no information on cybergrooming victimization prevalence rates, risk factors, or outcomes was provided, (d) they were reviews, conceptual articles or qualitative studies, or (d) were from the areas of computer science, for example on algorithmic cybergrooming detection, or legal science, for example on national legal frameworks.

Titles, abstracts, and full texts were screened independently by the first and second author to evaluate whether the respective study met all inclusion criteria. All conflicts were resolved by discussion with a third rater (last author). Interrater reliability (Cohen’s Kappa) was κ = 0.74 for title and abstract screening and κ = 0.89 for full-text screening. Thus, the interrater reliability can be considered substantial for title and abstract screening and almost perfect for full-text screening (Landis & Koch, 1977).

Coding System

The studies were coded independently by two raters using a coding manual tailored to the review’s objectives. Coding criteria are presented in the Supplementary Materials Table 1. Cohen’s Kappa was calculated for all criteria that were coded using a single-choice question (see Supplementary Materials Table 1). The average interrater reliability for these criteria was κ = 0.82, and for each criterion, the interrater reliability was at least substantial (Landis & Koch, 1977), with a minimum κ of 0.64 for the age group. Free text fields or multiple-choice questions were used to code all other criteria. All coding discrepancies were discussed in consultation with the third rater until a consensus was reached.

Quality Assessment of Included Studies

Since only quantitative studies were included in the present review, the GRADE system (Ryan & Hill, 2016) and its implementation by Fischer et al. (2021) were employed to assess the quality of included studies with regard to the present review’s research questions. First, a baseline assessment of a study’s quality was carried out based on three criteria, namely cybergrooming definition and cybergrooming victimization assessment according to the four core aspects aforementioned (use of information and communication technologies, minors being approached, sexual purposes, rapport building), and the research question’s focus on cybergrooming victimization. This assessment resulted in an initial classification as high or low quality. Methodological concerns, namely (a) an inadequate description of samples or methods, (b) suspected bias in samples or methods, or (c) small sample sizes (below 300; refer to Ryan & Hill, 2016), led to a downgrade in initial quality. Upgrades in quality were possible if (a) secondary findings on cybergrooming victimization that were not anticipated theoretically were presented and discussed with regard to the current state of research and theory, or (2) authors provided suggestions on how the study’s limitations can be addressed in future research. This had to be done in such a comprehensive way that an upgrade was justifiable. The overall quality was categorized as high, moderate, low, or very low. The final quality score reflects the consensus reached by the two raters through a double-blind process and subsequent discussion.

Results

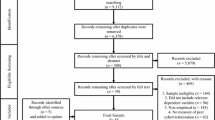

The search strategy identified a total of N = 523 publications, of which n = 216 duplicates were removed by the reference manager used (Zotero 6.0.30) or manually. Title and abstract screening resulted in the exclusion of n = 248 publications. Two publications could not be retrieved for full-text screening although the respective authors were contacted. After the full-text screening of N = 57 publications, n = 33 publications comprising n = 34 studies were included in the present systematic review. The overall screening process and reasons for exclusion in the full-text screening are depicted in Fig. 2.

Main Characteristics of Included Publications and Underlying Studies

All 33 included publications were published as peer-reviewed journal articles between 2012 and 2024. Most of the studies were cross-sectional studies (n = 27), and the minority were longitudinal (n = 3), or randomized controlled trials (RCTs; n = 4). In each RCT, an intervention group received an intervention targeting cyber victimization instead of the control group. In these studies, no distinction was made between the intervention and control groups in the presentation of results of relevance to this review. The possibility of a bias—concerning the present research questions—in the results based on the data after carrying out the intervention cannot be ruled out. Therefore, only the pre-test findings in each RCT were included.

A large proportion of included studies comprised data from Spain (n = 20) and Germany (n = 6), while other countries of recruitment were rarely represented. Only four studies collected data in multiple countries, allowing a cross-national comparison of cybergrooming victimization. Four studies were retrospective, i.e., adult participants were surveyed on their experiences as minors. In all other studies, participants were children and adolescents, predominantly between 11 and 18 years. Only two studies included a sample of participants under the age of 11. Therefore, the results presented here relate primarily to adolescence rather than childhood.

In fourteen studies, cybergrooming victimization was assessed through the Questionnaire for Online Sexual Solicitation and Interaction of Minors with Adults (QOSSIA; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2018a). The QOSSIA comprises two subscales, namely sexual solicitation and sexual interaction. The sexual solicitation subscale refers to sexual requests and contact attempts that do not necessarily involve a reaction from young people (e.g., “An adult asked me for pictures or videos of myself with sexual content”). In contrast, the second subscale measures sexual interactions in which young people actively participate (e.g., “I have maintained a flirtatious relationship with an adult online”). Overall, questionnaires were predominantly used for assessment, while other methods, namely single items and global assessment, were only employed occasionally. Global assessment means that the definition of the term cybergroomer was presented to the participants who had to state how often they had contact with someone fitting the definition (e.g., Wachs et al., 2016). Concerning the reference period, approximately half of the studies (n = 16) assessed cybergrooming victimization in the past twelve months. For the remaining studies, the reference period varied from one month to childhood and adolescence, and several studies lacked information on the reference period. The cut-off criterion for cybergrooming victimization was a rather low threshold across studies, as in most studies it was sufficient for a participant to be classified as a victim if they indicated that they had experienced one of the situations described by the measurement instrument at least once during the reference period. In almost all included studies (n = 32), participants were questioned about cybergrooming perpetrated by adults or relatively older persons. Only one study explicitly differentiated between peer and adult cybergrooming (Villacampa & Gómez, 2017). Table 1 provides an overview of the main characteristics of the studies included.

The final quality of most of the included studies was rated as moderate (n = 13) or high (n = 10). The overall quality was rated low in four or very low in seven studies (see Table 2). In several cases, the baseline quality was rated low because the presented definition was inadequate, i.e., it did not contain the previously defined minimum criteria (i.e., use of information and communication technologies, minors being approached, sexual purposes, rapport building).

Prevalence Rates of Cybergrooming Victimization

The included studies are heterogeneous in terms of the methodology used to determine the prevalence rates (different measurement instruments, reference periods, cut-off criteria for victimization) and the type of reported prevalence rates (overall prevalence rates, specific prevalence rates, prevalence rates by groups). All prevalence rates are provided in the Supplementary Materials Table 2. Overall, the majority of all reported prevalence rates, regardless of type, were above 10%, with a few exceptions, for example, three overall prevalence rates, some subscales, e.g. sexual interaction, and some prevalence rates for boys. Thus, it can be estimated that at least one in ten young people is victimized in some way by a cybergroomer. This section does not present prevalence rates by groups as these prevalence rates were reported by socio-demographic variables (gender, age, nationality, school type). Findings on these variables will be presented in the section on risk factors.

Overall Prevalence Rates

The overall prevalence rate was defined as a single value being reported for cybergrooming for the entire sample. Thirteen studies reported overall prevalence rates ranging from 5.4 to 31.1% (see Fig. 3). In more than half of those studies (n = 9), the reported prevalence rate ranged between 12.2 and 23%, whereby the prevalence rates in two studies were based on the same data (González-Cabrera et al., 2021; Machimbarrena et al., 2018). However, particularly in the case of overall prevalence rates, the methodology used to determine them was highly inconsistent as there were scarcely any rates based on the same combination of measurement instrument, reference period, and cut-off criterion. For example, the prevalence rate of 23% was determined based on a very broad single item asking for having a long, ongoing online conversation with an adult stranger (Greene-Colozzi et al., 2020), while the prevalence rate of 12.2% was determined based on a very specific single item asking for being deceived by an adult with a fake profile to make sexual or intimate requests (Alonso-Ruido et al., 2024).

Overall prevalence rates in total sample and by gender. Dashed lines serve as orientation and are positioned at 10 and 20%. t = measurement time point. For Tintori et al. (2023), the data point for the total sample is covered by the data points by gender

Three prevalence rates were strikingly low, with 5.4% (Finkelhor et al., 2022), 6.5% (Wachs et al., 2012), and 7.2% (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2018b). However, Wachs et al. (2012) chose a very strict cut-off criterion, namely at least once a week, compared to most other included studies. In Gámez-Guadix et al. (2018b), the prevalence rate was calculated based only on one subscale of the measurement instrument employed, namely sexual interaction from the QOSSIA. Responses to the sexual solicitation subscale were neglected in the prevalence rate calculation in contrast to most other studies employing the QOSSIA. Finkelhor et al. (2022) did not provide precise information on the calculation of the prevalence rate. One prevalence rate stood out due to its magnitude of 31.1% (Almeida & Barreiros, 2024). However, this figure includes victimization before, during, or after the COVID lockdown, i.e., the reference period was much longer than in most other studies.

Specific Prevalence Rates

Specific prevalence rate means that more than one prevalence rate was reported, for example, for subscales of the measurement instrument employed or victim types related to the stability of victimization. Prevalence rates according to stability of victimization were presented in two longitudinal studies. One of them reported separate prevalence rates for victims only at measurement point one (t1) (11.8%), victims only at t2 (one year later) (12.7%), and stable victims over t1 and t2 (10.9%) (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2023). In the second study, prevalence rates were reported separately for new victims (14%), ceased victims (4.4%), intermittent victims (1.6%), and stable victims (6.7%) based on three measurement points over a total of 13 months (Ortega-Barón et al., 2022). When added together (35.4 and 26.7%, respectively), these figures approach the above-mentioned high overall prevalence rate of 31.1% (Almeida & Barreiros, 2024).

In five studies, prevalence rates were reported separately for the subscales of the QOSSIA, sexual solicitation and sexual interaction. Prevalence rates for sexual solicitation were consistently higher than those for sexual interaction. Leaving aside the very high prevalence rates of 30.2% for sexual solicitation and 18.9% for sexual interaction (Almeida & Barreiros, 2024), the prevalence rates for sexual solicitation ranged from 11.3 to 17.8% and for sexual interaction from 4.8 to 7.9%. Therefore, the overall prevalence rate of 7.2% presented above (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2018b) was reasonable, as it only reflected sexual interaction. In two other studies that used questionnaires with subscales, specific prevalence rates also differed by subscale (Bergmann & Baier, 2016; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2021). Exact figures can be found in the Supplementary Materials Table 2. In two studies in which cybergrooming victimization was assessed globally, prevalence rates were reported for each response option (Wachs et al., 2012, 2016). The response option “once a year” was chosen by 10.4 and 10.9% of participants, respectively, while the response options “once a month”, “once a week”, and “several times a week” altogether were selected by 10.8 and 7.6% of participants respectively.

Risk Factors for and Outcomes of Cybergrooming Victimization

In the included studies, a variety of potential risk factors and outcomes of cybergrooming victimization were investigated, some factors very frequently (e.g., gender, age, cyberbullying), others only in a single study (e.g., guilt, pornography consumption). Since most included studies had a cross-sectional design that did not allow conclusions regarding the temporal relationship, it was difficult to reliably determine investigated factors as risk factors or outcomes. In addition, a bidirectional association between several investigated constructs and cybergrooming victimization could be assumed. Thus, a classification into risk factors and outcomes is refrained from in this section. As an empirical basis for identifying examined factors as risk factors is lacking, no classification into person and situational factors according to the proposed model is made in this section. Instead, the results below are presented by a content-driven categorization of all examined factors. All factors investigated in the included studies are presented in content-driven categories in Fig. 4. Table 3 shows which categories of investigated factors were included in each study.

Socio-Demographic Variables

Most of the studies in this systematic review (n = 25) analyzed gender as a potential risk factor for cybergrooming victimization, with a significant portion (n = 16) indicating that girls are generally at higher risk of cybergrooming victimization or at least more vulnerable to certain aspects of cybergrooming compared to boys. Only a few studies indicated no gender differences (n = 6), two of which focused on sexual interaction. Three studies showed that boys might be more at risk (Arias Cerón et al., 2018; Hernández et al., 2021; Tintori et al., 2023). However, the conclusiveness of these three studies about gender differences in cybergrooming victimization was limited. First, in one study, the measurement of cybergrooming victimization with two very specific single items was considered inadequate in the quality assessment (Arias Cerón et al., 2018). Second, in Tintori et al. (2023), the latent factor on which boys scored higher was not a pure cybergrooming victimization factor, but a mixture with hyperconnectivity operationalized by screen time, while there were no significant differences in prevalence rates by gender, which were based only on the cybergrooming items. Similarly, in Hernández et al. (2021), the mean values for boys were slightly higher, while there were no significant differences in prevalence rates. Looking in more detail at gender differences, some included studies revealed a tendency for girls to be more involved in sexual solicitation by perpetrators than boys but not in sexual interactions (Alonso-Ruido et al., 2024; Calvete et al., 2021b, 2023; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2018a). Longitudinally, however, gender assessed at t1 predicted t2 sexual interaction, with being a boy increasing the risk of being involved in sexual interaction (Calvete et al., 2021b). As most studies included gender as a binary variable in their analyses, statements about other genders are impossible in this review.

Age was also frequently examined as a risk factor (n = 16). Nine studies provided evidence that the risk of cybergrooming victimization increases with age. There were age differences in overall cybergrooming victimization and subscales such as sexual solicitation and sexual interaction from the QOSSIA. Six studies found no age differences, and only one study indicated that children are more at risk than adolescents (Villacampa & Gómez, 2017). Although several studies have found cross-sectional evidence of a link between age and cybergrooming victimization, in a longitudinal study, the predictive power of t1-age for t2-sexual interaction disappeared (Calvete et al., 2021b).

Further socio-demographic variables were only investigated in very few studies. However, these studies indicated that other socio-demographic variables might also play a risk-increasing role in cybergrooming victimization, e.g., school type (Arias Cerón et al., 2018; Machimbarrena et al., 2018), nationality (Wachs et al., 2016), parental educational level (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2023; Villacampa & Gómez, 2017), and sexual orientation (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2018a, 2023). These studies suggested that going to a public rather than a private school, being Thai rather than Western, having parents with lower educational level, and being homo- or bisexual are associated with a higher risk of being targeted by perpetrators, thereby leading to cybergrooming victimization. The findings regarding migration background and the parents’ relationship status were inconclusive in that no differences were found (Bergmann & Baier, 2016; Wachs et al., 2012) or that stable cybergrooming victims were more likely to have a migration background and separated parents than non-victims (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2023; Wachs et al., 2012).

Internet Usage Behavior

Four studies investigated the relationship between cybergrooming victimization and problematic Internet use and consistently found a positive association (Calvete et al., 2021b; Machimbarrena et al., 2018; Tamarit et al., 2021; Wachs et al., 2015, 2018). However, in a longitudinal path analysis, problematic Internet use at t1 was marginally associated with less sexual interaction at t2 (Calvete et al., 2021b). Another study found positive correlations between cybergrooming victimization and facets of Internet addiction, namely addiction symptoms, social media use, geek behavior, and nomophobia, i.e., the fear of staying disconnected from the Internet (Tamarit et al., 2021). Still, the predictive power for cybergrooming victimization disappeared within a structural equation model for the latter. Strengthening the results on problematic Internet use, the amount of Internet usage was positively associated with cybergrooming victimization (Wachs et al., 2012), or at least facets of cybergrooming victimization, namely communication about personal matters and pretended feelings (Bergmann & Baier, 2016).

A positive correlation between the factor of chat platform usage and sexual solicitation and interaction was found (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2018a). However, from a more differentiated perspective, only communication via adult chat platforms predicted facets of cybergrooming, but communication via children chat platforms did not (Bergmann & Baier, 2016). Furthermore, in the case of peer grooming, more victims commonly used social networks than chat platforms, while in the case of adult grooming, victims used both equally (Villacampa & Gómez, 2017).

Risk-Seeking Behavior

Seven studies investigated factors that constituted the category of risk-seeking behavior. Overall, the evidence indicated that risk-seeking behavior is positively associated with cybergrooming victimization. Risk-seeking as a general behavioral tendency predicted all four facets of cybergrooming identified in one study (Bergmann & Baier, 2016). Furthermore, risky online behavior was associated with cybergrooming victimization, namely having strangers on one’s buddy list (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2018a), indiscriminate enlargement of social networks, and engaging in intimate and face-to-face relationships with strangers met online (Longobardi et al., 2021), willingness to meet with strangers (Wachs et al., 2012), and online disclosure of private information (Wachs et al., 2020). Cybergrooming was also positively correlated with risky offline activities (Wachs et al., 2015, 2018), whereby both studies mentioned were based on the same sample.

Personality Traits

Four studies have linked cybergrooming victimization to (body) self-esteem. In two studies, self-esteem was found to be a significant predictor of cybergrooming victimization, with low self-esteem increasing the risk of cybergrooming victimization (Pasca et al., 2022; Wachs et al., 2016). However, findings differed when two dimensions of body self-esteem, perceived physical attractiveness and body satisfaction, were considered (Schoeps et al., 2020; Tamarit et al., 2021). In both studies, perceived physical attractiveness was positively related to cybergrooming victimization. The results were ambiguous concerning body satisfaction, indicating either no or a negative relationship, although both studies were based on the same original sample.

Overall, however, personality traits were only investigated in a few studies, and not all personality traits investigated were associated with cybergrooming victimization, e.g., the dark triad (Resett et al., 2022). In Hernández et al. (2021), all personality traits investigated (neuroticism, extraversion, disinhibition, lack of empathy, narcissism) were correlated with cybergrooming victimization. Still, only disinhibition remained significantly predictive within a structural equation model for both genders. Dispositional mindfulness and risk perception were investigated as protective factors for cybergrooming victimization, but negative correlations were found only with some facets of dispositional mindfulness (Calvete et al., 2020).

Mental Well-Being

Three studies investigated depressive and anxiety symptoms in relation to cybergrooming victimization. In all three studies, depressive symptoms were positively associated with cybergrooming victimization, while this pattern was only found in two studies for anxiety symptoms. Noteworthy, longitudinal analyses showed that t2-victims exhibited more symptoms of depression at t1 than non-victims (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2023), indicating that depressive symptoms could not only be an outcome of cybergrooming victimization but also a risk factor. Further studies revealed that cybergrooming victimization might negatively affect mental well-being, for example, in terms of lower health-related quality of life (Calvete et al., 2020; Ortega-Barón et al., 2022) and negative emotional impact (Finkelhor et al., 2023). One study investigated shame and guilt as an outcome of cybergrooming victimization and found that stable victims had higher shame and guilt scores at t1 than t1-victims, indicating that those feelings could contribute to the persistence of victimization (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2023). Finally, coping strategies with risky situations are also related to mental well-being (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2020). However, coping strategies were only investigated in one study (Wachs et al., 2012). It was found that aggressive coping was associated with less and cognitive-technical coping with more cybergrooming victimization.

Other Types of Victimization

Seven studies consistently showed that cybergrooming victimization is positively associated with cyberbullying victimization. Likewise, an association between cybergrooming and traditional bullying victimization could also be assumed, albeit based on fewer studies (n = 3). In both studies, in which both forms of bullying were assessed (Wachs et al., 2012, 2015), cybergrooming victimization was more strongly associated with cyberbullying than traditional bullying victimization. The reviewed studies also showed overlaps between cybergrooming victimization and other forms of victimization. For example, a positive correlation between cybergrooming victimization and cyber dating abuse victimization was found (Calvete et al., 2020, 2023; Machimbarrena et al., 2018). Further, a range of other types of victimization (conventional crimes, child maltreatment, peer/sibling victimization, sexual victimization, witnessing/indirect victimization) were investigated as risk factors for cybergrooming victimization (Almeida & Barreiros, 2024). Although cybergrooming victimization was correlated with all of them, only peer and sibling victimization and sexual victimization were found to be significant predictors of cybergrooming victimization in a multiple regression analysis. Sexual solicitation and interaction were positively associated with experiencing online peer aggression (Calvete et al., 2023). Furthermore, associations with other victimization experiences were found, which, however, can be conceptualized as a proximal outcome of the cybergrooming process, namely sextortion (Almeida & Barreiros, 2024; Alonso-Ruido et al., 2024; Tamarit et al., 2021), and sexual coercion, sexual pressure, and unwanted exposure to sexual content (Longobardi et al., 2021).

Perpetrating Behavior

Four studies investigated the association between cybergrooming victimization and cyberbullying perpetration. Studies found predominantly positive correlations, except for one study finding that sexual interaction from the QOSSIA is uncorrelated with cyberbullying perpetration (Calvete et al., 2021a—Study 2). Correspondingly, one study found a positive correlation between cybergrooming victimization and traditional bullying perpetration (Wachs et al., 2015). The three studies that assessed both (cyber)bullying victimization and perpetration (Calvete et al., 2021a—Study 2; Calvete et al., 2020; Wachs et al., 2015) showed a strong tendency for cybergrooming victimization to be more closely related to (cyber)bullying victimization than perpetration.

Additionally, cybergrooming victimization or sexual solicitation but not sexual interaction was positively associated with cyber dating abuse perpetration (Calvete et al., 2020, 2023). Both sexual solicitation and interaction were positively correlated with online peer aggression perpetration (Calvete et al., 2023). However, for these types of perpetrations, too, the same tendency was evident as for cyberbullying, namely that the association with cybergrooming victimization was weaker than that involving the respective kind of victimization instead of perpetration.

Sexual Behavior

Eleven studies investigated the relationship between sexting and cybergrooming and consistently showed positive correlations of sexting with both cybergrooming and sexual solicitation and sexual interaction as subscales. In most cases, sexting also remained significant as a predictor in multiple regression analyses in these studies. However, in a longitudinal study, t2-sexting was marginally predicted by t1-sexual solicitation but not t1-sexual interaction, and t2-sexual interaction was not predicted by t1-sexting (Calvete et al., 2021b). Sexting could, therefore, be an outcome of receiving sexual solicitations but was longitudinally unrelated to sexual interactions. Since the predictive power of t1-sexting for t2-sexual solicitation was not tested, no statement can be made as to whether this longitudinal relationship was bidirectional. In addition to sexting, other factors from this category were also associated with cybergrooming, namely the consumption of pornography (Alonso-Ruido et al., 2024) and sexual advancement strategies (Schoeps et al., 2020). Although all three advancement strategies, namely direct, coercive, and indirect, were highly positively correlated with cybergrooming victimization, the latter strategy no longer predicted cybergrooming victimization in a structural equation model.

Family

Factors assigned to the family category were only rarely investigated overall. In two studies, parental control was used to predict cybergrooming victimization, but it was not a significant predictor in either study (Almeida & Barreiros, 2024; Bergmann & Baier, 2016). In one study, a lack of parental supervision on social media and apps was associated with higher factor scores on a factor analysis-derived factor for cybergrooming victimization (Tintori et al., 2023). However, this factor represented a mixture of cybergrooming victimization and hyperconnection. Therefore, the differences in factor scores could also be attributed to the factor’s hyperconnection-related aspects.

A distinction must be made between specific strategies when considering parental mediation strategies to manage children’s Internet use in the context of cybergrooming victimization: sexualized communication and sexual requests were both positively associated with restrictive mediation but negatively related to instructive mediation (Wachs et al., 2020). Instructive mediation is characterized by actively involving young people in establishing online safety, for example, through open discussions and education, as well as interest in regularly visited websites and availability for questions on the part of the parents. In contrast, restrictive mediation means that online safety is sought primarily by setting rules without involving young people, restricting websites, and controlling their online behavior (Wachs et al., 2020). Thus, this kind of mediation can potentially undermine young people’s striving for autonomy as a crucial developmental process in adolescence. Family support could be another protective factor for cybergrooming victimization, given the observed negative predictive power (Pasca et al., 2022), while parental care was not associated with cybergrooming victimization (Bergmann & Baier, 2016).

Mediators and Moderators

Potential mediators and moderators of the relationship between cybergrooming victimization and risk factors or outcomes have been studied less than mere risk factors or outcomes (n = 4 for mediators and n = 3 for moderators). Figure 5 depicts all mediators and moderators investigated, including the mediated or moderated relationships.

Overall, the evidence on mediators of the relationship between risk factors and cybergrooming victimization was relatively weak, as no more than one study was on any mediation process. Erotic and pornographic sexting were considered mediators in two studies, which, however, were based on the same original sample. Both studies indicated that both types of sexting play a mediating role in the effect of body attraction and disinhibition on cybergrooming victimization (Schoeps et al., 2020) or of Internet addiction symptoms and geek behavior on cybergrooming victimization (Tamarit et al., 2021). In both cases, the independent variables positively predicted both types of sexting, which in turn directly (Tamarit et al., 2021) or indirectly over sexual advancement strategies (Schoeps et al., 2020), positively predicted cybergrooming victimization. Further findings on mediation processes indicated that low self-esteem could mediate the effect of cyberbullying victimization on cybergrooming victimization (Wachs et al., 2016) and that online disclosure could mediate the effect of instructive and restrictive parental mediation on cybergrooming victimization (Wachs et al., 2020). None of the included studies investigated mediation processes related to cybergrooming victimization and potential outcomes.

The evidence for potential moderators of the relationship between risk factors and cybergrooming victimization was also very sparse or even non-existent for moderators of the relationship between cybergrooming victimization and outcomes. In all three studies in which moderation analyses were performed, gender was a relevant moderator. In a longitudinal study, it was found that t2-t1 sexual solicitation predicted sexual interaction at t2 more strongly for boys than for girls (Calvete et al., 2021b). Multigroup factor analysis revealed that narcissism was predictive of cybergrooming victimization for boys but not for girls (Hernández et al., 2021). Furthermore, there was evidence that sexting predicts sexual solicitation and interaction in girls but only sexual interaction in boys (Resett et al., 2022).

Discussion

As information and communication technologies have increasingly become an integral and natural part of young people’s lives, it is crucial to understand how prevalent online risks like cybergrooming victimization are, how to prevent them, and how to mitigate their adverse outcomes. The systematic analysis of existing research on the prevalence, risk factors and outcomes of cybergrooming victimization contributes to building profound knowledge in this regard. However, previous research syntheses on risk factors and prevalence rates have been narrative, while reviews on outcomes are lacking to date. This systematic review aimed to provide an overview of the international body of research on prevalence rates, risk factors, and outcomes of cybergrooming victimization, informed by an adaptation of the General Aggression Model (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Kowalski et al., 2014). Findings from 34 studies indicated that, despite heterogeneity in the measurement of cybergrooming victimization and thus variability in reported prevalence rates, it can be assumed that at least one in ten young people is affected by cybergrooming. Several factors associated with cybergrooming victimization were identified. However, due to the cross-sectional design of most studies, they can only be classified into risk factors, outcomes, and co-occurrences on a theoretical basis, which will be presented in the following. Research on mediators and moderators of the relationship between cybergrooming victimization and associated factors is scarce.

Prevalence Rates

The included studies reported different prevalence rates, categorized here in terms of overall, specific, and prevalence rates by groups. Most reported prevalence rates exceeded 10% but were characterized by heterogeneity. Differences in the methodology in terms of measurement of cybergrooming, the composition of the sample (e.g., age and gender), and country of data collection are likely to contribute to the wide range of prevalence rates, particularly regarding overall prevalence rates ranging from 5.4 to 31.1%. The issue of heterogeneity in reported prevalence rates is not a phenomenon unique to cybergrooming but also applies to many other forms of youth victimization, such as child sexual abuse (Barth et al., 2013), cyberbullying (Kowalski et al., 2014), and cyber dating abuse (Caridade et al., 2019). However, reported overall prevalence rates for cybergrooming victimization were predominantly in the range between 12 and 20%. Remarkably low or high overall prevalence rates could largely be attributed to the underlying methodology. It can be discussed whether these figures overestimate how many young people have experienced the manipulative process that constitutes cybergrooming as opposed to single occurrences of sexual solicitation or harassment. This is because employed measurement instruments potentially do not clearly delineate between cybergrooming victimization and overlapping phenomena such as sexual solicitation. For example, with the Questionnaire for Online Sexual Solicitation and Interaction of Minors with Adults, participants mainly were classified as victims if they had experienced any type of sexual solicitation or interaction at least once. If participants stated that they had experienced the described situation once or twice for only one sexual solicitation item, e.g., “An adult asked me for pictures or videos of myself with sexual content”, but not for any other item, this would instead characterize a single occurrence of sexual solicitation. However, when considering the more straightforward global measurement of cybergrooming victimization, with which the participants were presented with a precise definition of a cybergroomer, still around 20% of participants stated that they had contact with a cybergroomer at least once in the past year (Wachs et al., 2012, 2016). It should also be considered that comparatively high prevalence rates (31.1, 35.4 and 26.7%) were found for longer reference periods (Almeida & Barreiros, 2024; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2023; Ortega-Barón et al., 2022). It can, therefore, be hypothesized that the prevalence is even higher in childhood and adolescence. Overall, these results show that consistent international standards for the measurement of cybergrooming victimization are needed to improve the comparability of research, for example, to understand time trends and cross-national differences.

When focusing on specific prevalence rates, it became evident that sexual solicitations occur more frequently than sexual interactions. A meta-analysis (Madigan et al., 2018) found a mean prevalence of 11.5% for sexual solicitations, which is at the lower end of the range of 11.3 to 17.8% seen in this review. This could be explained by the fact that the meta-analysis focused on unwanted sexual solicitations, whereas sexual solicitations are not always unwanted within the cybergrooming process. It is also conceivable that the cybergrooming process is initiated by sexual solicitation, as in some cases, requests for sexual behavior are made within minutes preceding the development of a relationship (Broome et al., 2018). Overall, it can be stated that prevalence rates varied depending on the specific grooming strategy or form of interaction, e.g., sexualization (11.1%) versus communication about personal matters not exclusively of a sexual nature (40.5%) or aggression (7.2%) versus the use of deception (16.5%).

Factors Associated with Cybergrooming Victimization

A plethora of factors potentially associated with cybergrooming victimization was examined in the included studies. Content-driven categories were formed to organize these factors: Socio-demographic characteristics, personality traits, mental well-being, family, Internet usage and access, risk-seeking behavior, other types of victimization, perpetrating behavior, and sexual behavior. Neither the pool of factors examined, nor the proposed categorization exhaustively represents risk factors and outcomes of cybergrooming victimization. First, a few factors investigated in the included studies could not be assigned to these categories. Second, some factors identified through qualitative research were missing from the studies included. For example, no included study examined loneliness or family difficulties as potential risk factors (Webster et al., 2012; Whittle et al., 2014), self-harm or problems with friends as potential outcomes (Whittle et al., 2013b).

Classification into Risk Factors, Outcomes, and/or Co-occurrences

Although most studies considered at least one potential risk factor, outcome, or co-occurrence, very few individual factors were investigated in more than three studies. However, a clear tendency emerged for several categories where affiliated factors appear to be relevant in cybergrooming victimization. Based on the theoretical argumentation of included studies and relevant additional research, a preliminary classification into risk factors, outcomes, and co-occurrences can be made, which needs to be empirically verified. This initial classification is subsequently used to embed the findings in the proposed model.

Overall, the included studies suggest that several socio-demographic characteristics are linked to cybergrooming victimization, representing vulnerabilities targeted by perpetrators, e.g., based on their preferences. These relevant socio-demographic characteristics include gender, age, nationality, sexual orientation, school type, and parental educational level. Most included studies analyzing gender indicated that girls are targeted more frequently by perpetrators than boys, which is consistent with findings on the role of gender in sexual victimization (e.g., Barth et al., 2013; Laird et al., 2020). The higher vulnerability of girls was linked to the fact that perpetrators are often male and heterosexual, that girls mature earlier, and that they exhibit more risky media usage behavior in relation to cybergrooming than boys (Wachs et al., 2012). Nevertheless, boys should not be neglected in the context of cybergrooming victimization because, for example, there was a tendency for gender differences to disappear in sexual interactions. It was proposed that although girls may be victims of sexual solicitations more frequently, they react to them less than boys (Calvete et al., 2021b). Although the evidence was not entirely unambiguous, there was a tendency for the risk of cybergrooming victimization to increase with age, indicating that cybergrooming becomes more prevalent throughout adolescence, which may be linked to increasing social Internet use and sexual curiosity.

Several studies found a positive association of cybergrooming victimization with problematic Internet use and the amount of Internet usage, suggesting that young people’s Internet usage behavior is relevant in the context of cybergrooming. Problematic Internet use was treated as a risk factor in the respective studies, which several arguments can justify. First, increased Internet use entails more contact opportunities for cybergroomers (Calvete et al., 2021b; Wachs et al., 2018). Second, problematic Internet usage is accompanied by a preference for online social interactions and relationships, making affected young people more vulnerable to cybergroomers’ efforts to make contact and build relationships (Calvete et al., 2021b; Wachs et al., 2018). Third, problematic Internet use can impair social integration (McIntyre et al., 2015), especially when used for socio-affective reasons (Weiser, 2001), diminishing potential protective factors.

The included studies provided evidence that risk-seeking behavior is associated with cybergrooming victimization, in particular risky online behavior, which was considered a risk factor in the respective studies. For example, by indiscriminately expanding social networks and disclosing information online, a greater number of strangers can gather personal information that facilitates access to potential victims and rapport building with them (Longobardi et al., 2021; Wachs et al., 2020). It can be argued that risky online behavior can be partly attributed to the fact that the Internet creates a perception of safety among young people, as it is associated with a feeling of anonymity and being unobserved and does not require physical presence (Wachs, 2014). This could encourage them to engage in risky online behaviors, such as carelessly connecting with strangers, who may exploit these connections via blackmail (Chiang & Grant, 2019). Alongside risky online behavior, risky offline behavior was also associated with cybergrooming victimization but was discussed both as a potential risk factor and outcome. For example, substance abuse as a specific risky offline behavior could impair self-control, which potential perpetrators may misuse. Still, it could also act as a negative coping mechanism for psychological distress after victimization (Wachs et al., 2015).

In several studies, cybergrooming victimization has been associated with impaired psychological well-being, for example, in terms of depressive and anxiety symptoms and decreased health-related quality of life. While the latter was consistently considered an outcome of cybergrooming victimization, depressive and anxiety symptoms were discussed as both risk factors and outcomes. Namely, cybergrooming victimization can cause depression and anxiety symptoms through traumatic dynamics, and conversely, victims exhibiting such symptoms could be more vulnerable to cybergroomers’ efforts (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2023). One of the included longitudinal studies found evidence for a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms but not anxiety symptoms and cybergrooming victimization (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2023). It would be desirable to conduct more longitudinal studies on this, considering that such a bidirectional relationship has already been meta-analytically established in the context of peer victimization and internalizing problems, which usually refer to depressive and anxiety symptoms, with greater effects for cyber victimization than for traditional forms of victimization (Christina et al., 2021).

There was only occasional evidence of links between cybergrooming victimization and personality traits, namely low self-esteem, body self-esteem, disinhibited behavior, some facets of dispositional mindfulness as a protective factor, and narcissism for boys. Therefore, statements on the existence or nature of typical personality profiles of victims are refrained from. The only personality trait examined in two independent studies was self-esteem (Pasca et al., 2022; Wachs et al., 2016). Low self-esteem is conceivable both as a risk factor, e.g., due to a low self-esteem-associated preference for communication via information and communication technologies, which is in turn exploited by cybergroomers, and an outcome of cybergrooming victimization (Wachs et al., 2016). Meta-analytical evidence for such a bidirectional relationship has already been found in the context of peer victimization and self-esteem (van Geel et al., 2018).

Findings from included studies strongly indicated that there is a link between cybergrooming victimization and other forms of victimization, especially cyberbullying. There are two possible explanations for the association between cybergrooming and other forms of victimization. On the one hand, victims of different forms of victimization may share some risk factors resulting in their co-occurrence (Wachs et al., 2012). On the other hand, one form of victimization could make victims vulnerable to other forms of victimization (Machimbarrena et al., 2018; Wachs et al., 2018). For example, one possible pathway might be that cyberbullying victimization enhances problematic Internet use (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2013), which in turn may lead to cybergrooming perpetrators targeting the victim. However, irrespective of the underlying mechanisms, this finding is worrisome, as polyvictimization proved to be particularly detrimental to health outcomes (e.g., Feng et al., 2019; Finkelhor et al., 2007), also in the context of digital polyvictimization (Hamby et al., 2018). Associations were also found between cybergrooming victimization and perpetrating behavior; however, these were smaller than with the respective victimization. A possible explanation for these associations involves the reciprocity between perpetration and victimization. Based on the General Aggression Model (Anderson & Bushman, 2002), perpetrating behavior can occur as aggressive behavior in response to experienced victimization (e.g., Calvete et al., 2023). First, cybergrooming victimization is likely to be correlated with a certain form of perpetration if it is correlated with the corresponding form of victimization as there is an intersection of people who are—due to the reciprocity—both perpetrators and victims of the respective phenomenon, e.g., in the case of cyberbullying (Lozano-Blasco et al., 2020). Second, considering reciprocity across phenomena, victims of cybergrooming may respond to this victimization with aggressive behavior such as cyber dating abuse perpetration. Apart from this explanatory approach, it was argued, based on bullies reporting an earlier start of dating, relationship orientation, and more advanced pubertal development (Connolly et al., 2000), that bullying perpetration, also transferred to cyberbullying perpetration, could be a risk factor for cybergrooming victimization (Wachs et al., 2015).

Among the sexual behavior category, sexting was examined most frequently in relation to cybergrooming victimization. Although sexting can be considered a healthy form of sexual exploration in adolescence (Lemke & Rogers, 2020), positive associations with cybergrooming victimization were found throughout the included studies. In most included studies investigating sexting, it was defined relatively broadly as the exchange of messages, images, or videos of sexual content over the Internet. All studies assessed active sexting, i.e., creating and sharing sexual content, rather than passive sexting, i.e., asking for, being asked, or receiving sexual content (Barrense-Dias et al., 2017). It is important to disentangle sexting that occurs as a co-product of the cybergrooming process and sexting that does not happen within the grooming process but with peers, for example. Although not all included studies on sexting did, some explicitly measured sexting with one’s partner or friends (e.g., Calvete et al., 2021b; Schoeps et al., 2020). It can, therefore, be assumed that there is an association between sexting and cybergrooming victimization beyond sexting as a co-product of the cybergrooming process. Although most included studies analyzed sexting as a correlate or predictor, it should be considered that sexting could be an outcome of cybergrooming victimization. Victims might adopt the belief that sharing sexual material is normal as it has been justified and normalized by the perpetrator during the grooming process (Gámez-Guadix & Mateos-Pérez, 2019).

Concerning factors related to family, only family support and parental mediation were each found to be significantly associated with cybergrooming in one study (Bergmann & Baier, 2016; Pasca et al., 2022; Wachs et al., 2020). Both were considered factors influencing the risk of cybergrooming victimization. It was argued that instructive mediation strengthens resilience and coping abilities with regard to Internet risks, while restrictive parental mediation can evoke adverse behaviors through rules set solely by parents (Wachs et al., 2020). Parental mediation could not be helpful or detrimental per se, but it depends on the chosen approach. Although the effects of different styles of parental mediation are not completely unambiguous, it was found, for example, that autonomy-supportive mediation, as opposed to restrictive mediation, decreases young people’s exposure to media violence (Fikkers et al., 2017) and that in line with previously described findings, restrictive parental supervision increases risky online behavior (Sasson & Mesch, 2014). In line with previous research (Whittle et al., 2014), family support was conceptualized as a protective factor against cybergrooming victimization, influencing the adolescent’s willingness to open up with a stranger (Pasca et al., 2022).

Embedding Results in the Theoretical Model

Figure 6 presents factors identified as relevant by included studies within the proposed model with minor extensions based on the preliminary categorization into risk factors, outcomes, and co-occurrences. Please note that while the differentiation between cybergrooming process and sexual abuse was retained in this model to suit the conceptualization of the phenomenon of cybergrooming, this differentiation was not well supported in the included studies. In some measurement instruments, items could be identified that can be clearly assigned to the cybergrooming process (e.g., “Lied to make me believe that we had things in common or that we liked the same things” from the Multidimensional Online Grooming Questionnaire) or sexual abuse (e.g., “We have met offline to have sexual contact” from the Questionnaire for Online Sexual Solicitation and Interactions With Adults). However, prevalence rates and associations with risk factors or outcomes were generally not reported at the item level for these items.

According to the modified version of the General Aggression Model (Kowalski et al., 2014) adapted to cybergrooming victimization, risk factors should be categorized into person and situational factors. However, other types of victimization discussed as potential risk factors cannot be clearly identified as characteristics of the person or the environment. They were, therefore, added to the model as a third input factor. The remaining factors associated with cybergrooming, which were provisionally classified as risk factors based on theoretical considerations, can be considered either person (e.g., age) or situational (e.g., parental mediation) but far more person than situational factors were identified. This raises the question of whether person factors have a greater impact on cybergrooming victimization than situational factors or if person factors have been examined more often in the studies (see Fig. 3).

Overall, fewer potential outcomes were examined and identified than risk factors. Still, it became apparent that distal outcomes affect different domains (e.g., psychological health, behavioral problems). Distal outcomes are conceptualized as adverse outcomes of victimization within the model. Although it is not a per se negative behavior, sexting was included here as it was discussed as a risk factor and outcome of cybergrooming victimization. Thus, as an outcome, it potentially increases the risk of revictimization. This applies to several outcomes, representing a possibility of how outcomes can feed back into inputs, for example, in the case of other types of victimization. However, the initial model fails to depict the third possibility of polyvictimization: Other forms of victimization could not be represented as co-occurrences that are neither risk factors nor outcomes caused by shared risk factors. This form of polyvictimization was added to the model.

Mediators and Moderators

Overall, the available evidence on mediating and moderating variables proved very limited. Only a few studies have tested mediation and moderation models for presumed risk factors and their effect on cybergrooming victimization, while not a single study has tested such models for the effect of cybergrooming victimization on potential outcomes. The available evidence suggested that sexting plays a mediating role between risk factors, e.g., disinhibition, and that gender plays a moderating role between risk factors, e.g., narcissism and cybergrooming victimization. Further research testing more complex models incorporating moderating and mediating variables is needed to gather information on which variables may buffer the effect of risk factors on cybergrooming victimization or the negative effect of cybergrooming victimization on outcome variables. For example, the type of parental mediation could be relevant not only for prevention, but also for mitigating adverse outcomes. Research on cyberbullying found that the association between bystanding and depression, subjective health complaints, and self-harm was strengthened by restrictive but weakened by high instructional mediation (Wright & Wachs, 2024). Further, it would be desirable to understand whether and how disclosure, i.e., confiding victimization experiences to other people, has an impact on the consequences of cybergrooming victimization. Research suggested that disclosure and the trusted person’s reaction can play an important role in mitigating the negative consequences of sexual victimization (e.g., McTavish et al., 2019; Ullman, 2002). Therefore, disclosure should be considered as a potentially relevant moderator in the context of cybergrooming victimization and its outcomes.

Limitations

First, regarding the inclusion criteria, studies were excluded from the systematic review if the term cybergrooming or a synonym (e.g., online grooming) was not mentioned verbatim. Thus, no studies on online sexual harassment, solicitation, or similar phenomena without reference to cybergrooming were included. This was a deliberate decision to clearly differentiate the construct of cybergrooming from these phenomena and to strengthen the terminology in research. As a result, some studies that do not explicitly refer to cybergrooming but examine conceptually comparable or overlapping phenomena may have been omitted. For example, no studies were included that examined sexual solicitations and interactions with the Questionnaire for Online Sexual Solicitation and Interaction of Minors With Adults without explicitly referencing cybergrooming (e.g., Kerstens & Stol, 2014; Santisteban & Gámez-Guadix, 2017), although cybergrooming was operationalized with this questionnaire in many included studies.

Second, only studies that employed a self-report measure of cybergrooming victimization were included in the present review. Self-reports are prone to biases, such as recall bias (e.g., Kihlstrom et al., 2000) and response tendencies (e.g., McGrath et al., 2010). Beyond common issues of self-reports, it may be problematic that some minors interpret their relationship with a cybergroomer as a genuine romantic relationship and, therefore, consider the behavior exhibited by the cybergroomer or by themselves as not relevant when answering items assessing cybergrooming victimization. Other sources of information on cybergrooming victimization could be consulted, namely police crime statistics and third-party reports, e.g., by parents and peers. However, these sources also contain biases. For instance, the criminal law definition of cybergrooming is relatively narrow. In Germany, for example, only cybergrooming of children up to the age of 14 can be prosecuted, which means that cybergrooming cases involving minors over the age of 14 are not recorded in crime statistics. Third-party reports might be biased as some victims of sexual victimization do not confide in others for various reasons, such as shame and fear of disbelief (McElvaney et al., 2014), leaving others unaware of the victimization due to non-disclosure.