Abstract

Students with attentional difficulties are at greater risk for reading difficulties. To address this concern, we examined the extent to which adding a mindful breathing exercise to individual reading fluency interventions would improve gains in reading fluency, student-reported attention, and student-reported stress. In a restricted alternating design, four students in grades 3–5 with teacher-reported difficulties in attention and reading participated in 12 intervention sessions that included reading fluency instructional strategies only or a mindful breathing exercise plus reading fluency instructional strategies. Based on visual and Bayesian analyses, there were no differences in within-session gains in reading fluency between conditions; however, one student had greater self-reported attention and less reported stress in intervention sessions that included the mindful breathing component. Implications of the study for future research integrating mindfulness practices in academic interventions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Reading is a complex skill that many students have difficulty learning to master (National Reading Panel 2000). Based on the 2013 National Assessment of Educational Progress, 65% of grade 4 students in the USA did not meet proficiency standards in reading (National Center for Education Statistics 2014), and studies on the prevalence of reading disabilities and difficulties across English-speaking countries indicate that these concerns are not limited to the USA (Vogel and Holt 2003). Learning to read can be particularly problematic for students with significant attentional difficulties (Ghelani et al. 2004; Willcutt et al. 2001). For example, children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) typically have difficulties with executive functioning (EF), including working memory, self-regulation, and attention (Barkley and Murphy 2011; Willcutt et al. 2005). These executive functions are also considered important in cognitive theories of reading development because difficulties in these areas limit cognitive resources available for word decoding and reading comprehension (Berninger et al. 2010; LaBerge and Samuels 1974); accordingly, students with attentional difficulties are at greater risk for reading difficulties (Ghelani et al. 2004; Willcutt et al. 2001). The purpose of the present study is to explore ways to improve the effectiveness of reading fluency interventions for children with significant attentional difficulties.

Reading Fluency

Development of reading fluency is critically important in constructing meaning from text (Kuhn and Stahl 2003), and dysfluent word reading is a core characteristic of students experiencing reading difficulties across languages, even those with more regular orthographies than English (Wimmer and Schurz 2010). The importance of fluency is emphasized in cognitive models of reading development—as word reading becomes more automatic, more cognitive resources (e.g. attention and working memory) are available to be used for comprehension (Berninger et al. 2010; LaBerge and Samuels 1974; Perfetti 2007). In addition, as students learn to read more fluently, they may be more motivated to read (Schiefele et al. 2012), which may further improve fluency and comprehension as their reading volume increases (Topping et al. 2007).

Due to the importance of reading fluency, many specific strategies to improve it have been developed and evaluated. In general, reading fluency improves with reading practice (Samuels 1979), but not all practice is considered equal. For example, simply studying word lists has been shown to be insufficient for improving reading fluency (LeVasseur et al. 2008), and students are more likely to benefit from practicing text in which words are provided in a meaningful context (Fleisher et al. 1979). Effective reading fluency interventions often include a repeated readings component, in which students re-read short passages until they reach fluency targets. Reading passages repeatedly gives the student the opportunity to practice difficult words and phrases (Samuels 1979) and has been found to be effective in improving reading fluency, as well as comprehension (Therrien 2004).

Attention, Automaticity, and Reading

Students who struggle with inattention, particularly during the time at which they are learning early literacy skills, have greater difficulty in developing reading fluency, with related risk for difficulty in reading comprehension as they continue in school (Ghelani et al. 2004; Willcutt et al. 2007). These findings of greater risk are consistent with cognitive processing theories of reading that emphasize the role of attention and working memory in reading automaticity (LaBerge and Samuels 1974); if a student’s limited cognitive processing resources are further taxed by non-automatic and effortful word identification, constructing meaning from text is likely to be challenging (Perfetti 2007). Attention is also important in the development of self-regulation of cognition and behavior, which along with working memory, are cognitive processes associated with reading achievement (Blair and Razza 2007; Swanson and O’Connor 2009; Zelazo and Lyons 2012).

In part due to these predictive relations between self-regulation and working memory with reading and other academic outcomes, researchers are increasingly interested in intervention approaches that can improve self-regulating capacity in children with attention difficulties and/or ADHD, rather than relying solely on pharmacological treatment (Zylowska et al. 2009). For example, research suggests that participation in programs that target self-regulating capacity, such as mindfulness interventions, can lead to higher grades, better work habits, and greater prosocial behavior among students (Benson et al. 2000; Schonert-Reichl et al. 2015). Although researchers have examined the effects of mindfulness interventions on academic outcomes (e.g. Benson et al. 2000; Linden 1973; Salomon and Globerson 1987; Schonert-Reichl et al. 2015), few, if any, have explored the integration of mindfulness practice with academic interventions. As a preliminary study in this area, we investigate the extent to which adding a brief mindful breathing component to a reading fluency intervention improves intervention efficacy for students who display attentional difficulties.

Promoting Mindfulness

The term mindfulness has been defined in a variety of ways, though most commonly, definitions refer to the act of bringing attention and awareness to the present moment (Garrison Institute 2005; Zelazo and Lyons 2012). Mindfulness is commonly referred to as a meta-awareness, or an ability to become aware without evaluating or judging a situation or thought (Kabat-Zinn 2003). Though the concept of mindfulness originates from Buddhist tradition, its modernized form is frequently used in clinical settings and in psychological research (Kabat-Zinn 2003; Zelazo and Lyons 2012). Zylowska et al. (2009) define mindfulness as a type of attention regulation training, representing an individual’s ability to select the most relevant sensations, memories, and stimuli among those that are being experienced.

There are a variety of procedures currently used to foster mindfulness; however, most techniques share a common goal of focusing attention on something, such as the breath or a sound, and increasing awareness of one’s thoughts (Greenberg and Harris 2012). One of the key elements of mindfulness practice is focusing on one’s breath (Napoli et al. 2005). Breathing is important to the regulation of the autonomic nervous system, and learning to attend to one’s breath has been shown to increase self-awareness and improve focusing of the mind (Davidson et al. 2003; Napoli et al. 2005; Salmon et al. 2009). Typically, mindfulness interventions for children and adolescents occur in small group settings and involve activities such as mindfulness meditation, breathing exercises, and/or yoga (Greenberg and Harris 2012). It is important to use simple instructions with children (Zelazo and Lyons 2012), and props such as musical instruments can be useful for encouraging focus on breathing and attention by helping children direct their attention to something concrete (Kaiser-Greenland 2010).

School-Based Mindfulness Interventions

Several questions need to be addressed regarding school-based mindfulness interventions, including how to successfully integrate mindfulness with academics, and the amount of time required for these practices to show an effect (Garrison Institute 2005). Several studies of multi-week, multi-component mindfulness interventions have shown positive effects on academic outcomes (Benson et al. 2000; Greenberg et al. 2003; Schonert-Reichl et al. 2015) and on measures of executive functions including self-regulation, working memory, and attention (Flook et al. 2010; Napoli et al. 2005; Schonert-Reichl et al. 2015; Zeidan et al. 2010; Zelazo and Lyons 2012). Because mindfulness interventions have largely been evaluated as complete, packaged programs without component analyses, it can be difficult to ascertain the most effective components or practices in multi-component mindfulness interventions that may lead to behavioral changes such as improvements in academic achievement.

Most school-based mindfulness programs are multi-week, multi-component interventions, and we know little about the required intensity and frequency of mindfulness exercises for positive outcomes to be obtained. Although studies of necessary dosage are limited in children, some studies conducted with adult populations suggest that it is possible to see immediate effects in cognitive variables such as memory after short mindfulness practice sessions (e.g. Alberts and Thewissen 2011). Additionally, shorter sessions of mindfulness practice may be more developmentally appropriate for children, who typically have a harder time sitting comfortably and focusing on their breath for more than 3 min (Burke 2010).

Current Study

The present study expands on previous studies of school-based mindfulness interventions by exploring the integration of mindfulness practices in academic interventions. Specifically, we add a brief mindful breathing exercise to evidence-based strategies to improve reading fluency (Therrien 2004) to determine whether the intervention is more effective for children with significant attentional difficulties. Two intervention conditions are compared: a reading fluency alone condition and condition with a brief mindful breathing exercise preceding reading fluency intervention. A restricted alternating treatment design is employed to differentiate intervention effects (Barlow and Hayes 1979) and to determine whether a brief mindful breathing exercise can produce immediate effects on an academic outcome, specifically gains in reading fluency. The following research questions are addressed:

Does Adding a Brief Mindful Breathing Exercise to a Reading Fluency Intervention Improve Reading Fluency?

We hypothesize that the reading fluency intervention with the brief mindful breathing exercise will enhance reading fluency more than the reading fluency intervention alone.

Does Participation in the Brief Mindful Breathing Exercise Result in Greater Attention and Less Stress as Indicated by Student Self-Report?

We hypothesize that students will report greater attention and less stress when the reading fluency intervention is preceded by the brief mindful breathing exercise.

Method

Participants

Four students, ranging from grades 3 to 5 in a private elementary school in Vancouver, British Columbia, participated in this study. They were identified by their classroom teachers as students demonstrating both reading and attentional difficulties relative to other students in the classroom. Participant demographics and selected results from baseline assessments are presented in Table 1. Pseudonyms are used in place of participants’ real names.

Measures

Inattention

During screening, classroom teachers completed behavior ratings using the inattention subscale of the Disruptive Behavior Disorder (DBD) rating scale (Pelham et al. 1992). The inattention subscale contains nine items rated from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Very much) that align with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (American Psychiatric Association 2000) ADHD criteria. Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were endorsed as Pretty much or Very much for four or more items, which is consistent with a symptom count method for scoring ADHD checklists (e.g. Nolan et al. 2001). The requirement of four inattention symptoms to be present was consistent with our intent to include students with some attentional difficulties in the classroom, but not necessarily a clinical diagnosis of ADHD Predominantly Inattentive type, which would require six symptoms to be present.

Cognitive Functioning

The Verbal Knowledge and Matrices subtests from the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition (KBIT-2; Kaufman and Kaufman 2004), were administered as brief indicators of cognitive functioning during screening. These subtests were selected because they represent two of the four abilities (comprehension-knowledge and fluid reasoning) most closely correlated with general intelligence (Kaufman and Kaufman 2004). Evidence of reliability and validity for the KBIT-2 is presented in Kaufman and Kaufman (2004). Participants were required to have scores on the KBIT-2 within two standard deviations of the mean.

Reading Fluency

Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) probes from the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, 7th ed. (Good and Kaminski 2011), were administered as indicators of reading fluency throughout the intervention. DIBELS ORF passages, available for grades 1 through 6, are brief, repeatable measures of student accurate reading rate on connected text. Students are asked to read short passages for 1 min, and errors (e.g. words mispronounced or omitted, and hesitations lasting longer than 3 s) are recorded. A “words read correctly per minute” (WCPM) score is calculated by subtracting the number of errors made from the total number of words read in 1 min (Good and Kaminski 2011). On ORF passages, WCPM is a reliable measure of rate of accurate oral reading, with rs > .90 for test-retest and inter-rater reliabilities, and r > .84 for alternate-forms reliability. Validity evidence indicates that WCPM on DIBELS ORF passages is moderately strongly correlated with other measures of overall reading (Good et al. 2013; Reschly et al. 2009).

Attention and Stress

During each intervention session, students were asked two questions as state level measures of attention and stress. Students rated, on a visual analog scale from 0 to 100% (0% = Extremely Difficult and 100% = Extremely Easy), the item: “How easy is it for you to pay attention, right now.” Next, they rated from 0 to 100% (0% = Extremely Relaxed and 100% = Extremely Stressed) the item: “How stressed do you feel, right now.” Students indicated their ratings on the visual analog scale by moving a bead on a wooden board slider.

Mindfulness Activities Questionnaire

A short questionnaire was administered at baseline to see whether students had previously engaged in contemplative practices such as yoga or meditation training. First, students were asked which activities they like to do for fun and in their spare time. Second, students were asked whether they took part in specific contemplative practices such as yoga or meditation (Garrison Institute 2005). Students were also asked whether they had any martial arts training (e.g. Tae Kwon Do). If students indicated that they participated in these activities, they were asked how long they have participated in the activity. Finally, students were asked whether their parents engaged in activities such as yoga, martial arts, or meditation as an indication of whether students have had exposure to such practices through their parents’ involvement.

Procedure

Recruitment and Screening

Once participants were identified by their classroom teacher as potential candidates for participation in the study, active consent was obtained from a parent or guardian through a signed form. Student verbal assent was also obtained. Following the consent process, the DBD inattention scale, KBIT-2, and mindfulness activities questionnaire were administered. All students met the screening requirements of four or more symptoms on the DBD inattention scale and scores within two standard deviations of the mean on the KBIT-2. In addition, DIBELS Next passages were administered in a survey-level assessment (Shapiro 2011) to determine optimal progress monitoring levels.

During the survey-level assessment, students initially were asked to read three DIBELS Next passages at their grade level for a period of 1 min each. If the student had a median WCPM score that fell within the 25th percentile for fall grade level norms, and the 75th percentile for spring grade level norms (Hasbrouck and Tindal 2006; Shapiro 2011), that level was considered to be the student’s instructional level. The procedure was repeated, either moving up or down in grade level, until an instructional level was found for each student. A colleague independently determined instructional level based on a review of the collected data to check agreement.

Intervention Implementation

Interventions began once an instructional reading level was identified for each student. Intervention sessions were conducted at the school of participating students, twice per week for a period of 6 weeks and a total of 12 sessions each. Sessions were administered by the first author. Intervention sessions lasted approximately 12 min for the reading fluency only (RF) condition, and approximately 15 min for the mindful breathing plus reading fluency (MB + RF) condition.

A restricted alternating treatment design (Barlow and Hayes 1979; Onghena and Edgington 1994) was used in order to examine the effectiveness of the brief mindful breathing exercise component. Each student received multiple sessions of both treatments, alternating the independent treatment conditions of RF and MB + RF. Randomization of condition occurred within pairs of sessions for each student to prevent the situation of having one treatment being concentrated at the beginning of the study (e.g. BBBBBCCCCC).

RF Condition

The RF condition was composed of instructional strategies aimed at improving reading fluency including timed repeated readings, modeling, and phrase-drill error correction. These strategies have been shown to increase reading fluency in students (Begeny et al. 2006; Daly and Martens 1994; Daly et al. 2005; Therrien 2004). During RF sessions, students were first asked to complete the attention and stress items and then required to complete three repeated readings of one DIBELS Next passage, which were timed for 1 min each. Scores from the first and third readings were recorded for data analysis. After the first timed reading, students were asked a comprehension question in which they were required to tell the administrator everything they remembered from the passage. Students then listened as the passage was modeled to them by the administrator, who paused periodically to let students fill in missing words to ensure that they were following along (Begeny 2009). After the second repeated reading, students participated in a phrase-drill error correction procedure, in which they re-read phases containing misread words three times each. After students completed the third repeated reading, there was a performance feedback component in which their performance on the first and third readings was graphed in terms of WCPM and number of errors. Positive praise statements were used throughout the reading intervention.

MB + RF Condition

In this condition, participants first completed a brief mindful breathing exercise. The mindful breathing procedure was adapted from an exercise in the MindUP Curriculum (Hawn Foundation 2011) and required the student to practice breathing and then sit and listen to the sound of a chime for as long as they could, while focusing on the rise and fall of their breath. They were instructed to bring their attention back to their breath when their mind began to wander. They then completed the attention and stress ratings before completing the RF intervention procedures as described previously. A detailed script for the mindful breathing exercise is presented in the Appendix.

Treatment Integrity and Inter-scorer Agreement

Following each intervention session, the interventionist completed a checklist of critical intervention steps. Throughout the intervention, 100% of steps were completed. Intervention sessions were audio recorded, and 33% of sessions (i.e. four out of 12 sessions for each participant) were examined by an independent rater, who confirmed that 100% of critical steps were completed by the interventionist for each session reviewed.

Audio-recorded screening assessments and intervention sessions were also examined by an independent rater to determine inter-scorer agreement on ORF measures. Overall inter-rater agreement for reading fluency was measured by calculating the concordance correlation coefficient (CCC; Lin 1989). Overall, inter-rater agreement was CCC = .995, with a 95% confidence interval of .992–.997, indicating very high agreement between raters overall (Quinn et al. 2009).

Data Analysis

Data from all intervention sessions were graphed and analyzed using visual analysis techniques. For ORF, the difference between the first and third repeated readings was calculated and graphed. We reported the difference between first and third readings as the primary ORF measure because (a) the difference can be directly compared to reported gains in prior studies with similar components to evaluate the general effectiveness of the fluency-building procedures and (b) the difference, as compared to performance on the third reading, should be less affected by passage to passage differences in difficulty, a general concern with ORF passage sets (Christ and Ardoin 2009). Although not presented in text, results based on performance on third readings are substantively the same as the presented results for the differences scores. Graphs were examined for clear separation in level between conditions as evidence of intervention effects (Barlow and Hayes 1979). In addition, study hypotheses were evaluated quantitatively with Bayesian models (Swaminathan et al. 2014). We fit multilevel models for each dependent variable that determined if mean differences between intervention conditions (for each student and overall) differed from zero, based on 95% credible intervals, while accounting for the nesting of observations within students and serial dependence of observations (i.e. first-order autocorrelation, ρ). Model estimates were used to calculate standardized mean difference effect sizes (Hedges et al. 2012) that were interpreted as follows: >.20 is small, >.50 is medium, and >.80 is large (Cohen 1988). The Bayesian models were specified with non-informative priors in OpenBUGS (Spiegelhalter et al. 2014), with a total of 400,000 draws from the posterior distribution, discarding the first 100,000 and thinning by a factor of 10 before computing model estimates and 95% credible intervals.

Results

Screening Assessments

As detailed in Table 1, symptom counts on the DBD Inattention subscale ranged from four to eight, indicating some degree of teacher concern with inattentive behavior in the classroom. Results of the survey level assessment indicated that two students (i.e. Claire and Emma) should be monitored one level below grade level. The remaining two students (i.e. Henry and Jacob) were monitored at their respective grade levels. It is important to note that although these students appeared to be performing within grade-level expectations based on our survey-level assessment criteria for determining instructional level, classroom teachers nominated the students for intervention based on perceived need for intervention based on reading performance relative to classroom peers. Cognitive screening results using the KBIT-2 indicated average scores (within 1 SD of the mean) on the Verbal Knowledge and Matrices tasks for Claire, Henry, and Jacob. Emma displayed an average score on the Verbal Knowledge task; however, her performance on the Matrices task was below average compared to most other children her age (1.73 SD below the mean). Regarding prior experiences with contemplative practices, one student, Henry, had participated in the MindUp curriculum (Hawn Foundation 2011) at his previous school and stated that he did engage in a short mindful breathing exercise before hockey practices and games. None of the other participating students reported having participated in contemplative practices.

Reading Fluency

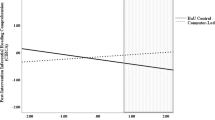

The difference in WCPM between the first and third timed reading on DIBELS Next passages in each session is displayed in Fig. 1. As detailed in Table 1, the mean gains were comparable across students (range 20.62 to 33.03 WCPM) and very similar across intervention conditions (RF 27.88 WCPM; RF + MB 28.36 WCPM). These gains are also quite comparable to the reported average within-session gains for a reading fluency intervention with very similar components (grade 2 students 22.76 WCPM; grade 3 students 24.52 WCPM) conducted by Martens et al. (2007). The graphs for most students indicate a high degree of overlap between conditions and/or high variability within conditions. These observations are consistent with the negligible standardized mean difference effect sizes found in the Bayesian analyses (−.07 to .08), with the 95% credible intervals for the effect sizes all containing zero (see Table 2). In sum, there were no consistent differences in within-session gains in reading fluency between conditions, either within or across students.

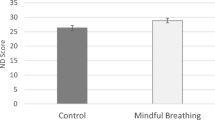

Attention Ratings

Ratings of attention provided before the reading fluency intervention procedures are displayed in Fig. 2. For three of the four students, the graphs demonstrate a high degree of overlap and/or variability between conditions. For Jacob, however, there was clear separation in attention ratings between conditions, with higher ratings of attention when the mindful breathing exercise was completed. The Bayesian analyses largely paralleled these results, with negligible to small effect sizes for all students other than Jacob, who demonstrated a large effect size of 1.03, with a 95% credible interval that did not contain zero.

Stress Ratings

Ratings of stress provided before the reading fluency intervention procedures are displayed in Fig. 3. Similarly to the attention ratings, there was high overlap between conditions and/or within-session variability for three out of four students. For Jacob, however, there was clear separation in stress ratings between conditions, with lower ratings of stress when the mindful breathing exercise was completed. Based on the Bayesian analysis, Jacob’s effect size of −0.83 was large, and the 95% credible interval for the effect did not contain zero.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of a brief mindful breathing exercise added to a reading fluency intervention on reading fluency, student-reported ability to pay attention in the present moment, and feelings of stress for four students in grades 3 to 5. We hypothesized that the reading fluency intervention with the added brief mindful breathing exercise would enhance reading fluency beyond the reading intervention alone and result in students being better able to pay attention and feeling less stress compared to when they did not participate in the brief mindful breathing exercise. Contrary to hypotheses, there were no demonstrated increases in within-session reading fluency in reading fluency when the mindful breathing exercise was added, and benefits in attention and stress were only evident for one out of the four participants in the study.

Limitations

Several limitations are important to note in the present study. First, with only four participants, external validity is limited. Generalizability of findings for other students in different types of school environments should not be assumed. Second, it is possible that using a measure of accurate reading rate as an indicator of reading proficiency may have missed changes in other areas of reading, e.g., prosody or reading comprehension. Third, student participants may have been reading too well to observe changes in reading fluency between conditions. Although all students were identified by teachers as experiencing reading difficulties relative to classroom peers, two students, Henry and Jacob, were instructional at their grade level, while the other two students, Claire and Emma, were instructional just one level below grade level. Fourth, the self-report ratings for stress and attention were created by the researcher because no brief, repeatable state-level mindfulness measures for children were found in the literature. Relatedly, it is possible that the ratings were not appropriate for the entire range of ages of participating students. Jacob was the oldest participant and the only participating student to exhibit a clear difference in self-report ratings between conditions. He may have had more insight into the purpose of the mindful breathing exercise and answered items accordingly, or it is possible that the rating system was not developmentally appropriate for the younger students participating in the study. Last, the dosage of mindful breathing practice may not have been substantial enough to yield a real change in reading fluency or on perceived feelings of attention and stress. Although some studies have found evidence for immediate outcomes on cognitive processes such as memory after brief mindfulness interventions (e.g. Alberts and Thewissen 2011; Mrazek et al. 2012), mindfulness training sessions are typically longer duration (i.e. 12–20 min) than in the present study (i.e. 3–5 min).

Implications for Practice

Although limited, the study’s findings suggest some potential applied implications. There were no overall gains in reading fluency when reading intervention was preceded by a mindful breathing exercise; however, there were improvements in self-reported attention and stress for one student, and also no attenuation of effects on reading fluency when the mindful breathing exercise was added. Therefore, reading interventionists may want to consider including a mindful breathing component if a student appears distracted, upset, or unfocused at the beginning of a session or if the student reports that such practices are helpful. Students could also be taught how to engage in the practice by themselves or to request such exercises on days when they feel they need it.

Additionally, the student-specific changes in self-reported attention and stress suggest that the same brief mindful exercise may not lead to the same self-perceptions of improvement for all students. Although mindfulness training is increasingly being used by teachers in classroom settings (Garrison Institute 2005; Greenberg and Harris 2012; Hawn Foundation 2011), it is important for teachers employing such techniques to consider that such exercises might not be equally effective for, or resonate with, all students in a classroom.

Future Research

Findings from the current study point to several areas of future research. First, the potential effects of an extended mindfulness exercise in reading interventions should be explored. As mentioned above, it is possible that the dosage of mindfulness training in the present study was not large enough to see a clear difference between conditions on reading outcomes. Participants such as Emma and Claire seemed reluctant to engage in the brief mindful breathing activity in the first few sessions. Both students seemed to enjoy the exercise more by the end of the intervention. Perhaps, students would have benefitted from more time practicing and becoming comfortable with the breathing exercise. It is also important for future researchers to examine the possibility that different measures of mindfulness may be more appropriate for older versus younger students, and how to effectively and repeatedly measure the construct of mindfulness, or mindful feelings, for students in elementary school.

Second, the finding of differential effectiveness of the mindful breathing exercise on student-reported attention and stress suggests that there could be important moderators of intervention effects that have yet to be identified. Accordingly, the characteristics of students who may benefit most from intervention components aimed at increasing feelings of mindfulness and attention should be explored. It is possible that older students, or students with combined limitations in working memory and reading, may benefit more from components of this kind. In line with this idea, Swanson and O’Connor (2009) found that for students with deficits in working memory, reading fluency practice such as repeated readings did not compensate for the demands of working memory required for comprehending text. In new investigations in these areas, it could be beneficial to incorporate working memory and reading comprehension measures, and not only measures of accurate reading rate, as in the current study.

Conclusion

The brief mindful breathing exercise employed in the present study did not enhance participants’ reading fluency and only had an effect on feelings of stress and ability to pay attention for one of the four participating students. However, findings suggested that adding components aimed at mindful breathing to reading fluency interventions did not negatively affect reading fluency, and so the addition of simple to implement mindful breathing exercises may still be worthwhile for students struggling with attention. Despite limitations in the present study, there remains a need for more research about effectively integrating mindfulness into the classroom and the dosage required for practices to be effective. Future research could also focus on the effect of mindful breathing exercises on other aspects of reading achievement, including comprehension, prosody, and expression, as well as ways to better measure feelings of mindfulness for children that can be used repeatedly, as was required in the present study. We hope that further exploration into the intersection of mindfulness training and academic achievement will help enable educators to more effectively engage students in learning, particularly those students with more difficulty paying attention in the classroom.

References

Alberts, H. J. E. M., & Thewissen, R. (2011). The effect of a brief mindfulness intervention on memory for positively and negatively valenced stimuli. Mindfulness, 2, 73–77. doi:10.1007/s12671-011-0044-7.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, (text rev4th ed.). Washington: Author.

Barkley, R. A., & Murphy, K. R. (2011). The nature of executive function (EF) deficits in daily life activities in adults with ADHD and their relationship to performance on EF tests. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 33, 137–158. doi:10.1007/s10862-011-9217-x.

Barlow, D. H., & Hayes, S. C. (1979). Alternating treatments design: one strategy for comparing the effects of two treatments in a single subject. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 12, 199–210. doi:10.1901/jaba.1979.12-199.

Begeny, J. C. (2009). Helping Early Literacy with Practice Strategies (HELPS): a one-on-one program designed to improve students’ reading fluency. Retrieved from http://www.helpsprogram.org

Begeny, J. C., Daly, E. J., & Valleley, R. J. (2006). Improving oral reading fluency through response opportunities: a comparison of phrase drill error correction with repeated readings. Journal of Behavioral Education, 15, 229–235. doi:10.1007/s10864-006-9028-4.

Benson, H., Wilcher, M., Greenberg, B., Huggins, E., Ennis, M., Zuttermeister, P. C., et al. (2000). Academic performance among middle-school students after exposure to a relaxation response curriculum. Journal of Research & Development in Education, 33, 156–165.

Berninger, V. W., Abbott, R. D., Swanson, H. L., Lovitt, D., Trivedi, P., Lin, S.-J., et al. (2010). Relationship of word- and sentence-level working memory to reading and writing in second, fourth, and sixth grade. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 41, 179–193. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2009/08-0002).

Blair, C., & Razza, R. P. (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development, 78, 647–663. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01019.x.

Burke, C. A. (2010). Mindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: a preliminary review of current research in an emergent field. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 133–144. doi:10.1007/s10826-009-9282-x.

Christ, T. J., & Ardoin, S. P. (2009). Curriculum-based measurement of oral reading: passage equivalence and probe-set development. Journal of School Psychology, 47, 55–75. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2008.09.004.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York: Academic Press.

Daly III, E. J., & Martens, B. K. (1994). A comparison of three interventions for increasing oral reading performance: application of the instructional hierarchy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 459–469. doi:10.1901/jaba.1994.27-459.

Daly III, E. J., Persampieri, M., McCurdy, M., & Gortmaker, V. (2005). Generating reading interventions through experimental analysis of academic skills: demonstration and empirical evaluation. School Psychology Review, 34, 395–414.

Davidson, R. J., Kabat-Zinn, J., Schumacher, J., Rosenkranz, M., Muller, D., Santorelli, S. F., et al. (2003). Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 564–570. doi:10.1097/01.PSY.0000077505.67574.E3.

Fleisher, L. S., Jenkins, J. R., & Pany, D. (1979). Effects on poor readers’ comprehension of training in rapid decoding. Reading Research Quarterly, 15, 30–48. doi:10.2307/747430.

Flook, L., Smalley, S. L., Kitil, M. J., Galla, B. M., Kaiser-Greenland, S., Locke, J., et al. (2010). Effects of mindful awareness practices on executive functions in elementary school children. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 26, 70–95.

Garrison Institute. (2005). Contemplation and education. In A survey of programs using contemplative techniques in K-12 educational settings: A mapping report. Garrison: Garrison Institute.

Ghelani, K., Sidhu, R., Jain, U., & Tannock, R. (2004). Reading comprehension and reading related abilities in adolescents with reading disabilities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Dyslexia, 10, 364–384. doi:10.1002/dys.285.

Good, R. H., & Kaminski, R. A. (2011). DIBELS Next assessment manual. Eugene: Dynamic Measurement Group.

Good, R. H., Kaminski, R. A., Dewey, E. N., Wallin, J., Powell-Smith, K. A., & Latimer, R. J. (2013). DIBELS Next technical manual. Eugene: Dynamic Measurement Group.

Greenberg, M. T., & Harris, A. R. (2012). Nurturing mindfulness in children and youth: current state of research. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 161–166. doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00215.x.

Greenberg, M. T., Weissberg, R. P., O’Brien, M. U., Zins, J. E., Fredericks, L., Resnik, H., & Elias, M. J. (2003). Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. American Psychologist, 58, 466–474. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.466.

Hasbrouck, J. E., & Tindal, G. A. (2006). Oral reading fluency norms: a valuable assessment tool for reading teachers. The Reading Teacher, 59, 636–644.

Hawn Foundation. (2011). The MindUp curriculum. Grades 3–5: brain-focused strategies for learning—and living. New York: Scholastic.

Hedges, L. V., Pustejovsky, J. E., & Shadish, W. R. (2012). A standardized mean difference effect size for single case designs. Research Synthesis Methods, 3, 224–239. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1052.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based stress reduction. Constructivism in the Human Sciences, 8, 73–107.

Kaiser-Greenland, S. (2010). The mindful child. New York: Free Press.

Kaufman, A. S., & Kaufman, N. L. (2004). Kaufman brief intelligence test (2nd ed.). Bloomington: Pearson.

Kuhn, M. R., & Stahl, S. A. (2003). Fluency: a review of developmental and remedial practices. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 3–21. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.3.

LaBerge, D., & Samuels, S. J. (1974). Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cognitive Psychology, 6, 293–323. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(74)90015-2.

LeVasseur, V. M., Macaruso, P., & Shankweiler, D. (2008). Promoting gains in reading fluency: a comparison of three approaches. Reading and Writing, 21, 205–230. doi:10.1007/s11145-007-9070-1.

Lin, L. I. (1989). A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics, 45, 255–268. doi:10.2307/2532051.

Linden, W. (1973). Practicing of meditation by school children and their levels of field dependence-independence, test anxiety, and reading achievement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 41, 139–143. doi:10.1037/h0035638.

Martens, B. K., Eckert, T. L., Begeny, J. C., Lewandowski, L. J., DiGennaro, F. D., Montarello, S. A., et al. (2007). Effects of a fluency-building program on the reading performance of low-achieving second and third grade students. Journal of Behavioral Education, 16, 39–54. doi:10.1007/s10864-006-9022-x.

Mrazek, M. D., Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2012). Mindfulness and mind-wandering: finding convergence through opposing constructs. Emotion, 12, 442–448. doi:10.1037/a0026678.

Napoli, M., Krech, P. R., & Holley, L. C. (2005). Mindfulness training for elementary school students: the attention academy. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 21, 99–125. doi:10.1300/J370v21n01_05.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2014). A first look: 2013 mathematics and reading. Washington: Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: an evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Bethesda: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Nolan, E. E., Gadow, K. D., & Sprafkin, J. (2001). Teacher reports of DSM-IV ADHD, ODD, and CD symptoms in schoolchildren. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 241–249. doi:10.1097/00004583-200102000-00020.

Onghena, P., & Edgington, E. S. (1994). Randomization tests for restricted alternating treatments designs. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 32, 783–786. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)90036-1.

Pelham, W. E. J., Gnagy, E. M., Greenslade, K. E., & Milich, R. (1992). Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 210–218. doi:10.1097/00004583-199203000-00006.

Perfetti, C. (2007). Reading ability: lexical quality to comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 11, 357–383. doi:10.1080/10888430701530730.

Quinn, C., Haber, M. J., & Pan, Y. (2009). Use of the concordance correlation coefficient when examining agreement in dyadic research. Nursing Research, 58, 368–373. doi:10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181b4b93d.

Reschly, A. L., Busch, T. W., Betts, J., Deno, S. L., & Long, J. D. (2009). Curriculum-based measurement oral reading as an indicator of reading achievement: a meta-analysis of the correlational evidence. Journal of School Psychology, 47, 427–469. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2009.07.001.

Salmon, P. G., Santorelli, S. F., Sephton, S. E., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (2009). Intervention elements promoting adherence to mindfulness-based stress reduction (MDSR) programs in a clinical behavioral medicine setting. In S. A. Shumaker, J. K. Ockene, & K. A. Riekert (Eds.), The handbook of health behavior change (3rd ed., pp. 271–286). New York: Springer.

Salomon, G., & Globerson, T. (1987). Skill may not be enough: the role of mindfulness in learning and transfer. International Journal of Educational Research, 11, 623–637. doi:10.1016/0883-0355(87)90006-1.

Samuels, S. J. (1979). The method of repeated readings. The Reading Teacher, 32, 403–408. doi:10.2307/20194790.

Schiefele, U., Schaffner, E., Möller, J., & Wigfield, A. (2012). Dimensions of reading motivation and their relation to reading behavior and competence. Reading Research Quarterly, 47, 427–463.

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Oberle, E., Lawlor, M. S., Abbott, D., Thomson, K., Oberlander, T. F., & Diamond, A. (2015). Enhancing cognitive and social–emotional development through a simple-to-administer mindfulness-based school program for elementary school children: a randomized controlled trial. Developmental Psychology, 51, 52–66. doi:10.1037/a0038454.

Shapiro, E. S. (2011). Academic skills problems: direct assessment and intervention (4th ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Spiegelhalter, D., Thomas, A., Best, N., & Lunn, D. (2014). OpenBUGS User Manual: Version 3.2.3. Retrieved from http://www.mrc-bsu.cam.ac.uk/bugs

Swaminathan, H., Rogers, H. J., & Horner, R. H. (2014). An effect size measure and Bayesian analysis of single-case designs. Journal of School Psychology, 52, 213–230. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2013.12.002.

Swanson, H. L., & O’Connor, R. (2009). The role of working memory and fluency practice on the reading comprehension of students who are dysfluent readers. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42, 548–575. doi:10.1177/0022219409338742.

Therrien, W. J. (2004). Fluency and comprehension gains as a result of repeated reading: a meta-analysis. Remedial and Special Education, 25, 252–261. doi:10.1177/07419325040250040801.

Topping, K. J., Samuels, J., & Paul, T. (2007). Does practice make perfect? Independent reading quantity, quality and student achievement. Learning and Instruction, 17, 253–264. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.02.002.

Vogel, S. A., & Holt, J. K. (2003). A comparative study of adults with and without self-reported learning disabilities in six English-speaking populations: what have we learned? Dyslexia: An International Journal of Research and Practice, 9, 193–228. doi:10.1002/dys.244.

Willcutt, E. G., Pennington, B. F., Boada, R., Ogline, J. S., Tunick, R. A., Chhabildas, N. A., & Olson, R. K. (2001). A comparison of the cognitive deficits in reading disability and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 157–172. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.157.

Willcutt, E. G., Doyle, A. E., Nigg, J. T., Faraone, S. V., & Pennington, B. F. (2005). Validity of the executive function teory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Biological Psychiatry, 57, 1336–1346. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.006.

Willcutt, E. G., Betjemann, R. S., Wadsworth, S. J., Samuelsson, S., Corley, R., Defries, J. C., et al. (2007). Preschool twin study of the relation between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and prereading skills. Reading and Writing, 20, 103–125. doi:10.1007/s11145-006-9020-3.

Wimmer, H., & Schurz, M. (2010). Dyslexia in regular orthographies: manifestation and causation. Dyslexia: An International Journal of Research and Practice, 16, 283–299. doi:10.1002/dys.411.

Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal, 19, 597–605. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014.

Zelazo, P. D., & Lyons, K. E. (2012). The potential benefits of mindfulness training in early childhood: a developmental social cognitive neuroscience perspective. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 154–160. doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00241.x.

Zylowska, L. L., Smalley, S. L., & Schwartz, J. M. (2009). Mindful awareness and ADHD. In F. Didonna (Ed.), Clinical handbook of mindfulness (pp. 319–338). New York: Springer.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported, in part, by scholarships from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada to the first and fourth authors and a research grant by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada to the second author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Authors Idler, Mercer, Starosta, and Bartfai declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research was supported, in part, by scholarships from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada to the first and fourth authors and an Insight Development research grant by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada to the second author.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendix

Appendix

The following is the script for the mindful breathing exercise used in this study. The script was adapted based on the Core Practice of the MindUP Curriculum (Hawn Foundation 2011).

-

1.

Invite the student to sit comfortably with their back against the chair, feet flat on the ground, and hands held loosely in their lap.

-

2.

Invite the student to take several breaths, breathing in through their nose and out through their mouth:

-

“Let’s take some deep breaths. Breathe in through your nose and out through your mouth. In 1, 2, 3, out 1, 2, 3. In 1, 2, 3, out 1, 2, 3. When you breathe in, take the breath all the way down to your tummy. In 1, 2, 3, out 1, 2, 3.”

-

3.

Ask the student to close their eyes and listen to the sound of the ringing instrument for as long as they can while paying attention to their breath:

-

“You will listen to the sound of this chime for as long as you can, while paying attention and focusing on the rise and fall of your breath.”

-

-

4.

Ring chime for the first time.

-

5.

Remind the student that if their mind wanders, it is alright. They just need to bring their attention back to their breath:

-

“It’s alright if your mind begins to wander. Just bring your focus back to your breathing. Feel the rise and fall of your breath in your tummy.”

-

-

6.

Tell student before ringing the chime a second time that they are to listen to the sound as long as they can, focusing on their breath and to raise their hand when they cannot hear it anymore:

-

“I am going to ring the chime again. Listen to the sound for as long as you can. When you can’t hear the sound any more, you can raise your hand.”

-

-

7.

Ring chime for the second time.

-

8.

Once student has raised their hand, invite the student to focus again on their breathing:

-

“Now slowly move your hand to your chest or tummy and feel your breathing. Just breathing in…just breathing out…”

-

9.

Wait another 30–45 s.

-

10.

Proceed with the reading fluency intervention procedures.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Idler, A.M., Mercer, S.H., Starosta, L. et al. Effects of a Mindful Breathing Exercise During Reading Fluency Intervention for Students with Attentional Difficulties. Contemp School Psychol 21, 323–334 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0132-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0132-3