Abstract

A brief breathing exercise designed to induce a mindful state could benefit reading comprehension performance, but has not been previously examined. Furthermore, the mechanisms of how an induced mindful state benefits cognition are not well understood. The purposes of this study are to test the effectiveness of a brief mindful breathing exercise on reading comprehension performance and examine two potential mechanisms (mind wandering and stress reduction). Undergraduate students (N = 105) engaged in either a mindful breathing exercise or control sham exercise, indicated their stress levels, and completed a reading comprehension assessment during which they self-reported their mind wandering. The mindful breathing exercise benefited performance, but the mechanisms for this benefit were not mind wandering or stress reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mindfulness, which is characterized by full attention and openness to the experiences of the present moment (Brown and Ryan 2004), has been noted to benefit performance on cognitive tasks (see Sedlmeier et al. (2012)). For this reason, it is not surprising that mindfulness training through two weeks of classes has been found to improve performance on the complex cognitive task of reading comprehension (Mrazek et al. 2013). However, mindfulness classes often demand more time and resources than educators or other individuals may be willing to dedicate (Zenner et al. 2014). For this reason, the benefits of quick, easily accessible practices that promote mindfulness, such as brief mindful breathing exercises (meditations), are important to examine (e.g., Bonamo et al. 2015; Cloutier 2011; Lloyd et al. 2016; see Hafenbrack (2017), for a review of such exercises in the workplace). These single sessions of mindful breathing exercises are thought to induce a state that benefits cognitional, though they are too brief to teach actual mindfulness skills (Hommel and Colzato 2017). However, the mechanisms that underlie the previously found benefits of brief mindful breathing exercises on cognition are not well understood (Bonamo et al. 2015). Thus, the purposes of this brief report are to (a) test the effect of a focused breathing exercise designed to promote a mindful state (i.e., a mindful breathing exercise) on reading comprehension performance and (b) to examine potential mechanisms should a benefit of the exercise be found.

Reading comprehension is cognitively demanding and complex, because multiple tasks must be completed simultaneously (Cain et al. 2004; Kintsch 1998). To successfully comprehend text, a reader must understand the individual words and connect the text to their background knowledge and other text (Graesser et al. 1997; Ozuru et al. 2009). For example, when reading a narrative, a reader must attend to characters, setting, goals, and actions, while incorporating relevant background knowledge that is not explicitly stated in the text in order to create a coherent mental representation (Trabasso and Van Den Broek 1985).

Even a brief mindful breathing exercise may enhance cognition leading to better performance on reading comprehension assessments. For instance, brief mindful breathing exercises have been shown to benefit performance on cognitive tasks such as memory (Bonamo et al. 2015; Lloyd et al. 2016; cf. Wilson et al. 2015, for opposing findings) and attention (Watier and Dubois 2016). However, there has not been a test of such exercises on reading comprehension, which involves the coordination of multiple cognitive tasks.

One reason to expect a benefit of a brief mindful exercise on reading comprehension is through a reduction in mind wandering. Mind wandering involves shifting one’s attention from the task at hand to task-unrelated thoughts (TUTs; Randall et al. 2014). Mind wandering has been noted to diminish performance in reading comprehension performance (e.g., Unsworth and McMillan 2013) perhaps due to the interference of distractions (McVay and Kane 2012; Smallwood et al. 2008). Moreover, mind wandering interferes with reading comprehension performance likely because the coupling between the reader and the text breaks down, leading to a reduced engagement with the text (Smallwood 2011).

Mindfulness is considered an opposing construct to mind wandering (Mrazek et al. 2012). Mindfulness training in classes over weeks or months has been shown to reduce mind wandering while reading likely because of increased focus on the task at hand (Mrazek et al. 2013; Zanesco et al. 2016). Even brief mindful breathing exercises have been found to reduce mind wandering (Mrazek et al. 2012; Rahl et al. 2017; Taraban et al. 2017). Therefore, if a brief mindful breathing exercise would enhance performance on a reading comprehension assessment, it is possible that it would be due to a reduction in mind wandering.

Another reason to expect that a brief mindful breathing exercise may help with reading comprehension performance is through reduced stress. Often, stress negatively influences an individual’s performance on certain cognitive tasks (Shields et al. 2016) that are critical for reading comprehension (Follmer 2018). Stress may consume cognitive resources because of pre-occupations with the sources of stress (Klein and Boals 2001).

Mindfulness training programs, such as through an eight-week workshop, are effective in reducing stress (Khoury et al. 2013, 2015). This is likely because mindfulness encourages focus on the present moment and not problems from the past or worries related to the future (Brown and Ryan 2004). In previous work, eight weeks of mindful movement through yoga improved performance on cognitive tasks due to its reduction of stress (Gothe et al. 2016). However, stress reduction has not been previously examined as an underlying mechanism of brief mindful breathing exercises influence on cognitive performance.

The primary purpose of this study is to test the effectiveness of a mindful breathing exercise on reading comprehension performance. It is hypothesized that engaging in a brief mindful breathing exercise prior to a reading comprehension assessment will benefit performance. Should such a benefit be found, the secondary purpose of this study would be to test two possible mechanisms, mind wandering and stress, that may underlie the effect.

To pursue these purposes, college students were the population of interest as they frequently report issues with mind wandering while reading (Jackson and Balota 2012). In addition, the college years are very stressful for many students, although it is often portrayed as a carefree time (Pierceall and Keim 2007). College students often feel overwhelmed by life transitions (e.g., moving away from home), the increase in school workload, and the need to establish new relationships (Galatzer-Levy and Bonanno 2013).

Methods

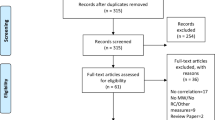

Participants (N = 105) were undergraduate students at a mid-sized public university in the USA. The average age was 20.35 years (SD = 2.89 years); approximately 60% identified as female and 40% identified as male. After providing informed consent, participants reported their current stress level with three five-point Likert-scale items in which they reported how calm (reverse scored), worried, and stressed they felt (Cronbach’s α = 0.75). They were randomly assigned to listen to one of two 15-min recordings: a mindful breathing exercise or a sham exercise (control condition; materials from Hafenbrack et al. (2014), adapted from Arch and Craske (2006).

In the mindful breathing exercise, the directions were to focus on breathing and attend to sensations in the present moment. Throughout the exercise, participants were reminded to attend to the sensations of breath with instructions such as “Focus your awareness. .. on the sensations of slight stretching. .. as the abdomen rises with each in-breath. .... . and of gentle deflation. .. as it falls with each out-breath.” Participants were informed to be aware of the experiences of the present moment with instructions such as “Now simply continue with this. .. perhaps reminding yourself from time to time. .. that the intention. .. is simply to be aware of your experience in each moment. .. as best you can.” Following Mrazek et al.’s (2013) experiment, participants were asked to rate how “absorbed in the present moment” (i.e., absorption rating) they were on a seven-point Likert scale after the exercise as well their current stress level using the same items as before (Cronbach’s α = 0.68). Then, participants had 20 min to answer 38 multiple-choice questions in the Nelson-Denny Comprehension Subtest Form G (ND test; Brown et al. 1993).

During the ND test, participants provided tallies of each time they caught their mind wandering (self-caught TUTs; see Mrazek et al. (2011)). After the ND test, participants completed a retrospective measure of TUTs with 16, five-point Likert items in which they indicated how often they thought about various topics unrelated to the task (Cronbach’s α = 0.87; Mrazek et al. 2013). Finally, participants reported their demographic information and were debriefed.

Results

As a manipulation check, a one-way ANOVA with condition as the independent variable and absorption ratings as the dependent variable was conducted. Participants who engaged in a mindful breathing exercise indicated greater absorption in the present moment (M = 5.20, SD = 1.01) than did participants in the control condition (M = 4.74, SD = 1.32), F(1, 103) = 3.92, p = .05, Cohen’s d = 0.38.

To examine the effect of the mindful breathing exercise on reading comprehension performance, a one-way ANOVA with condition as the independent variable and the number correct on the ND test as the dependent variable. As hypothesized, participants who engaged in the mindful breathing exercise had higher scores on the ND test than did participants who engaged in a sham exercise, F(1, 103) = 5.67, p = .02, Cohen’s d = 0.46 (see Fig. 1).

To assess the role of mind wandering, two separate one-way ANOVAs with exercise condition as the independent variable were conducted. The dependent variables were the self-caught TUTs and the retrospective measure of TUTs. Results indicated that there were no reliable differences in self-caught TUTs by condition, F(1, 103) = 1.76, p = .19 (see Fig. 2). Moreover, there were no reliable differences in the retrospective measure of TUTs by condition, F(1, 104) = 1.29, p = .26 (see Fig. 3).

To assess the role of stress levels, a one-way ANCOVA with condition as the independent variable, post-exercise stress levels as the dependent variable, and pre-exercise stress levels as the covariate was conducted. Participants who engaged in a mindful breathing exercise reported lower post-exercise stress levels than did participants who engaged in a sham exercise, F(1, 102) = 5.34, p = .02, Cohen’s d = 0.38 (see Fig. 4). Pre-exercise stress levels were significant as a covariate, F(1, 102) = 38.60, p < .001. Next, the statistical effects of post-exercise stress level on reading comprehension performance were examined. A hierarchical linear regression analysis was then conducted in which ND scores were the dependent variable, pre-exercise stress level, was entered into the first step of the regression model and post-exercise stress level was added in the second step of the regression model. As shown in Table 1, results indicated no statistical effects of stress level on reading comprehension performance.

Discussion

Based on the findings of this experiment, participants who engaged in a mindful breathing exercise prior to taking a reading comprehension assessment had better performance on a reading comprehension assessment than did participants who engaged in a sham exercise designed not to promote mindfulness. This builds on previous findings from extensive mindfulness training (Mrazek et al. 2013) and indicates that even a brief mindful breathing exercise can yield benefits in reading comprehension performance. Practically, the findings from this study may be useful as a method to improve performance on complex cognitive tasks such as reading comprehension assessments. Furthermore, the findings have pedagogical implications for teachers who wish to incorporate mindfulness practices into their classes. Given the importance of reading comprehension skills in many occupations (Carnevale 2013), the findings may be of practical use in the workplace as well (Hafenbrack 2017).

We had hypothesized the mindful breathing exercise would reduce mind wandering, but this is not what was found. It should be noted that this specific exercise has not been previously examined for an effect on mind wandering. One reason could be related to the different types of mindful exercises (meditations). These exercises can be broadly categorized as focused attention meditation (FAM), in which one is guided to attend to an event or object, or open monitoring meditation (OMM), in which one is guided to be open and aware to experiences in the present moment (Lippelt et al. 2014). The exercise used in this study incorporated elements of FAM, by encouraging focus on the breath, as well as OMM, by prompting awareness of the present moment. Given that mind wandering was not affected, it does not appear that focused attention was enhanced by the mindful breathing exercise (see Zanesco et al. (2016)). However, the exercise may have increased openness to experiences, which could have in turn induced a more flexible cognitive control state in which incoming information is better monitored (Hommel and Colzato 2017). Given that flexible cognitive control could promote better coordination of the multiple tasks involved in reading comprehension (Cain et al. 2004; Colé et al. 2014; Kintsch 1998), this change in flexible cognitive control could be a mechanism for the noted benefit of a mindful breathing exercise on reading comprehension.

The mindful breathing exercise reduced perceived stress, which is consistent with our hypotheses and previous findings (Khoury et al. 2013). However, this stress reduction was not associated with performance on the reading comprehension assessment. Therefore, the benefit of the mindful breathing exercise on reading comprehension performance could not be due to stress reduction. One reason for this lack of an association could be that the stress levels were relatively low for both conditions. Without stress levels high enough to interfere with cognitive performance in either condition, it is understandable that stress levels had no effect on reading comprehension performance (see Baumeister (1984), Haleem et al. (2015), and Yerkes and Dodson (1908) for discussions of findings on stress levels and cognitive performance). However, to our knowledge, this is the first study that reports on stress reduction from a single session of a mindful breathing exercise, which adds to its practical implications.

One key limitation of this study is that the mechanisms for the noted benefits with reading comprehension are unclear. One possibility is that the mindful breathing exercise promoted awareness and energized the participants (Brown and Ryan 2004), making them more alert for the task. Meditation has been positively associated with subjective vitality in the workplace (Fritz et al. 2011); therefore, a future study with measures of subjective vitality could examine this potential mechanism. Despite unanswered questions regarding the mechanism, the noted benefit of a mindful breathing exercise adds to the evidence supporting the use of mindfulness techniques in educational (Zenner et al. 2014) and workplace settings (Hafenbrack 2017).

References

Arch, J. J., & Craske, M. G. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness: emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(12), 1849–1858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.007.

Baumeister, R. F. (1984). Choking under pressure: self-consciousness and paradoxical effects of incentives on skillful performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(3), 610–620. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.3.610.

Bonamo, K. K., Legerski, J. P., & Thomas, K. B. (2015). The influence of a brief mindfulness exercise on encoding of novel words in female college students. Mindfulness, 6(3), 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0285-3.

Brown, J. I., Fishco, V. V., & Hanna, G. (1993). Nelson–Denny reading test: manual for scoring and interpretation, forms G & H. Riverside: Riverside Publishing Co..

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Perils and promise in defining and measuring mindfulness: observations from experience. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 242–248. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph078.

Cain, K., Oakhill, J., & Bryant, P. (2004). Children’s reading comprehension ability: concurrent prediction by working memory, verbal ability, and component skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.1.31.

Carnevale, A. P. (2013). 21st century competencies: for college and career readiness (pp. 1–9). Broken Arrow: National Career Development Association.

Cloutier, S. E. (2011). Mindful breathing in the classroom to increase academic scores. Teaching Innovation Projects,1(1), Art. 2. Retrieved from http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/tips/vol1/iss1/2

Colé, P., Duncan, L. G., & Blaye, A. (2014). Cognitive flexibility predicts early reading skills. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00565.

Follmer, D. J. (2018). Executive function and reading comprehension: a meta-analytic review. Educational Psychologist, 53(1), 42–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2017.1309295.

Fritz, C., Lam, C. F., & Spreitzer, G. M. (2011). It's the little things that matter: an examination of knowledge workers’ energy management. Academy of Management Perspectives, 25(3), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2011.63886528.

Galatzer-Levy, I. R., & Bonanno, G. A. (2013). Heterogeneous patterns of stress over the four years of college: associations with anxious attachment and ego-resiliency. Journal of Personality, 81(5), 476–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12010.

Gothe, N. P., Keswani, R. K., & McAuley, E. (2016). Yoga practice improves executive function by attenuating stress levels. Biological psychology, 121, 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2016.10.010.

Graesser, A. C., Millis, K. K., & Zwaan, R. A. (1997). Discourse comprehension. Annual Reviewof Psychology, 48(1), 163–189. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.163.

Hafenbrack, A. C. (2017). Mindfulness meditation as an on-the-spot workplace intervention. Journal of Business Research, 75, 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.01.017.

Hafenbrack, A. C., Kinias, Z., & Barsade, S. G. (2014). Debiasing the mind through meditation: mindfulness and the sunk-cost bias. Psychological Science, 25(2), 369–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613503853.

Haleem, D. J., Haider, S., Perveen, T., & Haleem, M. A. (2015). Serum leptin and cortisol, related to acutely perceived academic examination stress and performance in female university students. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 40(4), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-015-9301-1.

Hommel, B., & Colzato, L. S. (2017). Meditation and metacontrol. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 1(2), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-017-0017-4.

Jackson, J. D., & Balota, D. A. (2012). Mind-wandering in younger and older adults: converging evidence from the sustained attention to response task and reading for comprehension. Psychology and Aging, 27(1), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023933.

Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V., et al. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 763–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005.

Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: a meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009.

Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: a paradigm for cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klein, K., & Boals, A. (2001). The relationship of life event stress and working memory capacity. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 15(5), 565–579. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.727.

Lippelt, D. P., Hommel, B., & Colzato, L. S. (2014). Focused attention, open monitoring and loving kindness meditation: effects on attention, conflict monitoring and creativity. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1083. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01083.

Lloyd, M., Szani, A., Rubenstein, K., Colgary, C., & Pereira-Pasarin, L. (2016). A brief mindfulness exercise before retrieval reduces recognition memory false alarms. Mindfulness, 7(3), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0495-y.

McVay, J. C., & Kane, M. J. (2012). Why does working memory capacity predict variation in reading comprehension? On the influence of mind wandering and executive attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(2), 302. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025250.

Mrazek, M. D., Chin, J. M., Schmader, T., Hartson, K. A., Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2011). Threatened to distraction: mind-wandering as a consequence of stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1243–1248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.011.

Mrazek, M. D., Franklin, M. S., Phillips, D. T., Baird, B., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). Mindfulness training improves working memory capacity and GRE performance while reducing mind wandering. Psychological Science, 24(5), 776–781. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612459659.

Mrazek, M. D., Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2012). Mindfulness and mind-wandering: finding convergence through opposing constructs. Emotion, 12(3), 442–448. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026678.

Ozuru, Y., Dempsey, K., & McNamara, D. S. (2009). Prior knowledge, reading skill, and text cohesion in the comprehension of science texts. Learning and Instruction, 19(3), 228–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.04.003.

Pierceall, E. A., & Keim, M. C. (2007). Stress and coping strategies among community college students. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 31(9), 703–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920600866579.

Rahl, H. A., Lindsay, E. K., Pacilio, L. E., Brown, K. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Brief mindfulness meditation training reduces mind wandering: the critical role of acceptance. Emotion, 17(2), 224–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000250.

Randall, J. G., Oswald, F. L., & Beier, M. E. (2014). Mind-wandering, cognition, and performance: a theory-driven meta-analysis of attention regulation. PsychologicalBulletin, 140(6), 1411–1431. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037428.

Sedlmeier, P., Eberth, J., Schwarz, M., Zimmermann, D., Haarig, F., Jaeger, S., & Kunze, S. (2012). The psychological effects of meditation: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(6), 1139–1171. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028168.

Shields, G. S., Sazma, M. A., & Yonelinas, A. P. (2016). The effects of acute stress on core executive functions: a meta-analysis and comparison with cortisol. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 68, 651–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.038.

Smallwood, J. (2011). Mind-wandering while reading: attentional decoupling, mindless reading and the cascade model of inattention. Language and Linguistics Compass, 5(2), 63–77.

Smallwood, J., McSpadden, M., & Schooler, J. W. (2008). When attention matters: the curious incident of the wandering mind. Memory & Cognition, 36(6), 1144–1150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818X.2010.00263.x.

Taraban, O., Heide, F., Woollacott, M., & Chan, D. (2017). The effects of a mindful listening task on mind-wandering. Mindfulness, 8(2), 433–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0615-8.

Trabasso, T., & Van Den Broek, P. (1985). Causal thinking and the representation of narrative events. Journal of Memory and Language, 24(5), 612–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-596X(85)90049-X.

Unsworth, N., & McMillan, B. D. (2013). Mind wandering and reading comprehension: examining the roles of working memory capacity, interest, motivation, and topic experience. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39(3), 832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0615-8.

Watier, N., & Dubois, M. (2016). The effects of a brief mindfulness exercise on executive attention and recognition memory. Mindfulness, 7, 745–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0514-z.

Wilson, B. M., Mickes, L., Stolarz-Fantino, S., Evrard, M., & Fantino, E. (2015). Increased false-memory susceptibility after mindfulness meditation. Psychological Science, 26(10), 1567–1573. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615593705.

Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 18(5), 459–482. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.920180503.

Zanesco, A. P., King, B. G., MacLean, K. A., Jacobs, T. L., Aichele, S. R., Wallace, B. A., et al. (2016). Meditation training influences mind wandering and mindless reading. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3(1), 12–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000082.

Zenner, C., Herrnleben-Kurz, S., & Walach, H. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions in schools—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00603.

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Alex Karie, Kristina Syversen, Lisa Swiontek, and Newzaira Khan for their assistance with data collection and entry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(XLSX 60kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clinton, V., Swenseth, M. & Carlson, S.E. Do Mindful Breathing Exercises Benefit Reading Comprehension? A Brief Report. J Cogn Enhanc 2, 305–310 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-018-0067-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-018-0067-2