Abstract

Objective

Racial disparities exist in health care, even when controlling for relevant sociodemographic variables. Recent data suggest disparities in patient-physician communication may also contribute to racial disparities in health care. This study aimed to systematically review studies examining the effect of black race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication.

Methods

A comprehensive search using the PRISMA guidelines was conducted across seven online databases between 1995 and 2016. The search resulted in 4672 records for review and 40 articles for final inclusion in the review. Studies were included when the sample consisted of black patients in healthcare contexts and the communication measure was observational or patient-reported. Data were extracted by pairs of authors who independently coded articles and reconciled discrepancies. Results were synthesized according to predictor (race or racial concordance) and communication domain.

Results

Studies were heterogeneous in health contexts and communication measures. Results indicated that black patients consistently experienced poorer communication quality, information-giving, patient participation, and participatory decision-making than white patients. Results were mixed for satisfaction, partnership building, length of visit, and talk-time ratio. Racial concordance was more clearly associated with better communication across all domains except quality, for which there was no effect.

Conclusions

Despite mixed results due to measurement heterogeneity, results of the present review highlight the importance of training physicians and patients to engage in higher quality communication with black and racially discordant patients by focusing on improving patient-centeredness, information-giving, partnership building, and patient engagement in communication processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The existence of racial disparities in healthcare in the United States is heavily documented [1–3], with much of this research focused on disparities between black and white patients. This focus on black-white racial disparities, as compared to other racial minorities (e.g., Asian), may be due to pronounced and historical inequalities between black and white patients in healthcare settings [4]. Prior research and recent statistics from the National Center for Health Statistics [5] indicate black patients consistently receive worse quality of care than their white counterparts.

In addition to patients’ race, racial discordance between patients and physicians also predicts worse quality of care, as compared to racial concordance. Racial concordance refers to having a shared identity between a physician and a patient regarding their race whereas racial discordance refers to patients and physicians having different racial identities. Racial discordance is associated with patients perceiving their care to be of lower quality compared to racially concordant pairs [6]. Although racial disparities in health outcomes are clearly documented, it is less clear what contributes to these racial and ethnic health disparities [7]. Factors such as health insurance status, socioeconomic status, access to care, and patient preferences all contribute to these disparities, but a report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) notes that they do not fully account for racial and ethnic disparities in the care received by patients [8].

That IOM report, which included a comprehensive analysis on disparities in clinical encounters, indicates that physicians’ own actions toward black patients may contribute to these healthcare disparities [8]. The discrepancies in physicians’ interactions and communication with patients are due in part to the race of the patient (black, white) but also to racial concordance between patients and physicians [9, 10]. Recent research paints a somewhat unclear picture about the connection between race and patient-physician communication. For example, data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey from 2002 to 2012 shows that racial concordance does not have a significant effect on black patients’ ratings of physician communication [11]. In contrast, other research indicates many of the health disparities seen between black and white patients, especially in cancer, may be heavily influenced by the communication within medical interactions [12].

Race-related attitudes among physicians, even if held implicitly, may influence the quality of communication in patient-physician interactions and thus impact the disparities in treatment and information exchange [12]. Data from prior systematic reviews show good patient-physician communication is associated with positive health outcomes [13], and previous research contains mixed findings on the effect of race and racial concordance on patient-provider communication [9–11]. Given these findings, better understanding of the influence of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication systematically across the research literature may be critical to understanding and ultimately reducing racial health disparities. To address the need for a more comprehensive view of the connection between race and patient-physician communication, the present systematic review will examine the research literature that looks at the effects of black/white patient race and patient-physician racial concordance on communication outcomes.

Racial disparities in communication are often approached from two perspectives: (1) examining whether black patients report and/or experience worse communication than white patients and (2) determining the effect of racially concordant (versus discordant) patient-physician interactions on the quality of patient-physician communication. The vast majority of this literature focuses on the first perspective. Since an IOM report released in 2002, there has been an increase in the number of studies examining the effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication within clinical encounters to address this issue. These studies examine multiple aspects of communication including quality of patient-physician communication (defined broadly as being patient-centered and/or patients’ rating their experience communicating with their physician as in a positive manner; e.g., “good”) [14–16], patient-physician communication satisfaction [9, 17], information giving (defined as the information regarding treatment, disease, etc. that a physician shares with a patient) [18, 19], partnership building (defined as approaching communication in a style that incorporates the patient as an active partner) [20, 21], participatory decision-making (defined as involving patients directly into communication regarding making decisions about their care) [10, 22], positive [23, 24] and negative affect or tone of physicians [24, 25], as well as talk time and length of visit [18, 26].

Communication is most often assessed either through observational coding of patient-physician encounters or through patients’ self-reports of communication quality and satisfaction. This breadth of variety in communication measurement approaches allows for a more nuanced view of potential racial differences in patient-physician communication generally as well as across multiple domains of patient-physician communication (e.g., quality, satisfaction). Furthermore, this variance in methods provides insight into potential systematic differences between studies that utilize observational versus self-reported measures to assess the communication measures. Prior research also notes that differences beyond patient characteristics, such as disease type and physician characteristics, may differentially influence communication quality outcome measures [27]. Because there are different purposes for medical communication—such as creating a good interpersonal relationship, exchanging information, and making treatment-related choices [27]—it is likely that physician specialty and clinical setting such as surgery, primary care, and oncology also heavily influence communication outcomes.

There has been an increased emphasis in the research literature on the need to better understand the effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication as indicated by the growing literature in this area. Despite this interest, to our knowledge, no systematic review has focused solely on reviewing the literature examining the effects of race and/or racial concordance on patient-physician communication outcomes. A related 2009 review by Meghani and colleagues [28], focusing on health outcomes broadly, included reviews of papers which examined the effect of racial concordance on patient-physician communication, but did not review studies examining the effect of patient race on patient-physician communication. That review found no clear pattern for the effect of racial concordance on patient-physician communication. To provide a more comprehensive and updated review of the literature, we systematically reviewed studies that examine the main effect of patient race (black versus white patients) as well as the interaction effect of physician and patient race (i.e., racial concordance of patients and physicians) on observational and patient-reported patient-physician communication. Furthermore, we examined whether these effects differ by clinical setting.

Methods

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [29]. Below, we outline our search strategy for locating and reviewing articles.

Literature Search Strategy

A comprehensive electronic literature search of all articles published between January 1, 1995 and June 14, 2016 was conducted in the following databases: PubMed/Medline (NLM), EMBASE (Elsevier), SCOPUS (Elsevier), PsycINFO (OVID), Web of Science (Thomas Reuters), Cochrane (Wiley), and CINAHL (EBSCO). All languages were included in the search strategy. Controlled vocabulary (MeSH, PsycINFO Thesaurus, CINAHL Headings, EMTREE) and keywords were used. Two broad concept categories were searched, and results were combined using the appropriate Boolean operators (AND, OR). The broad categories included professional-patient relations and race relations. Related terms were also incorporated into the search strategy to ensure all relevant papers were retrieved. For a complete list of the MeSH and keyword terms used to conduct this search strategy, please refer to Table 1.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Peer-reviewed, quantitative studies were included in the study if they had a patient population sample, compared black to white patients or racial concordance to discordance, assessed patient-physician communication within a medical setting, and measured communication through audio/video recordings or observation and/or patient surveys. The search was narrowed to the U.S. and to the years between 1995 and 2016 to capture a more modern state of race relations in the U.S., which have varied across time and encompass a unique history. Exclusion criteria included: (1) not an adult patient/health setting; (2) not original data (e.g., meta-analysis, systematic review); (3) not our concept of patient-physician communication (e.g., not with physician providers, use of standardized patients, measured trust only); (4) no comparative analysis between black versus white patients or racial concordance; (5) not a U.S. study in English; (6) communication measure was only assessed post-intervention; and (7) communication was not a clear dependent variable.

Review Process

Using the inclusion/exclusion criteria outlined, studies were screened for inclusion in three phases. In the first phase, two authors independently reviewed titles for duplicates and poor fit with the focus of this systematic review. Disagreements were reconciled by having the author who coded the article for inclusion re-review the article and determine if she still thought it met the inclusion criteria. If that author maintained her decision to include the study at this stage, the article moved to the next round of review. This process was repeated for the abstract and full text review phases. Disagreement occurred with less frequency at each stage as follows: (1) 10.5% disagreement at the title review phase, (2) 10% disagreement at the abstract review phase, and (3) 8% disagreement at the full text review stage. The most common reasons for disagreement in eligibility were related to whether the outcome represented our domain of interest and whether the study contained black/white comparisons.

Data Extraction

Two authors independently extracted data from all eligible studies and reconciled discrepancies as necessary. Authors extracted the following items from the studies: sample characteristics (sample size, sex, % black, and mean age); the patient population studied; the study design and methods, how communication was operationalized, measured, and the type of measurement; and summaries of main findings of the study.

Results

Summary of Included Articles

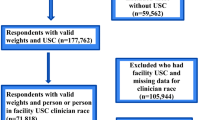

The search resulted in 4672 records. A total of 40 articles were considered suitable for final inclusion in this review. Many of these articles focused on a variety of health contexts, including primary/general care and cancer. Figure 1 contains the PRISMA flow chart describing our search and review process.

Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 summarize the included 40 articles, with each table focused on one of the following patient-physician communication domains: (1) communication quality (being patient centered and/or patients perceiving their communication interaction as positive; most commonly used the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) [30]), (2) communication satisfaction (patients’ degree of satisfaction with communication), (3) information-giving (patients’ sharing information regarding diagnosis, prognosis, treatment options, etc.), (4) partnership building (communication in a style that promotes patients’ participation), (5) patient participation and participatory decision-making (degree to which patient actively participates in conversation and/or decision-making), (6) positive and negative affect/talk (amount of physician talk with positive or negative affect), (7) length of visit/time and talk-time ratio, and (8) “other.” These categories were created based on the communication outcomes most commonly referenced in the included research literature. Within these categories, results were subdivided into observational and patient-reported measures. Because 15 articles [10, 18, 20, 21, 23–25, 31–38] reported findings on two or more different domains of communication, the total number of unique findings reported across all tables equals 72. The majority of findings focused on the quality of patient-physician communication (n = 17), satisfaction with patient-physician communication (n = 12), or length of visit/time for patient-physician interactions (n = 10).

Patient-Physician Communication Quality

The patient-physician communication quality findings were fairly evenly split across observational (n = 7) and patient-reported (n = 10) measures (Table 2). Nearly all the studies were cross-sectional in design and data were collected through observer ratings and outside coders of audio recordings of patient-physician interactions or through patient-reported surveys of quality of communication. Assessment of quality of communication varied across studies. For studies using observational measures of quality, the most common measurement was the Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS) [39], but several studies assessed quality using their own investigator-developed measures of quality. For studies using patient-reported measures of quality, measurement varied widely and tapped into quality domains such as interpersonal exchange, fairness, and respect [16], as well as physicians explaining things clearly and paying attention to patient concerns [37, 40, 41]. The most common measure of patient-reported quality of communication was a 4-item aggregate of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) [30] that assessed quality of physician communication on items such as how well and clearly the physician communicates [11, 35, 42, 43].

Across all 17 studies examining the quality of patient-physician communication, the majority indicated that black patients experience a lower quality of patient-physician communication, whether this was measured observationally or through patient report. Five of the 17 studies examined the effect of racial concordance on the quality of patient-physician communication. Results indicated no significant effect of racial concordance on the quality of patient-physician communication.

The majority of studies of communication quality occurred within primary care settings. Most of the studies in primary care settings found that race (but not racial concordance which, as noted, had no significant effect on outcomes) had a negative effect on communication quality. The one study of HIV/AIDS indicated that black patients had better quality of communication than white patients [43].

Observational Studies

Looking only at the seven observational studies assessing patient-physician communication quality, nearly all (n = 6) indicated that patient-physician communication for black patients is of lower quality than for white patients. This held true across a variety of quality measures. Only one study reported that the quality of patient-physician communication was higher among black than white patients [34]. Specifically, this study found that physicians spent a larger percentage of time with black patients structuring the interaction than they did with white patients and providing specific substance use assessment or advice. As noted, the three studies examining the effect of racial concordance on observational measures of communication quality found no significant association between racial concordance and quality of communication.

Patient-Reported Measures

Among the ten studies with patient-reported measures of patient-physician communication quality, the findings were more mixed. Half of these studies (n = 5) indicated that black patients reported having worse quality of patient-physician communication than white patients whereas four indicated that black patients reported having better quality of patient-physician communication than white patients. Only one study [37] showed no significant difference between black and white patients on a 6-item measure of general quality of patient-physician communication (paying attention, clarity of explanations, and advice). Among those studies examining racial concordance’s effect on patient-physician communication quality (n = 2), both found that there was no significant association between racial concordance and quality of communication [41, 44].

Patient-Physician Communication Satisfaction

Results were mixed across the 12 studies examining satisfaction with patient-physician communication (Table 3). All of these studies assessed patient-physician communication satisfaction with patient-reported measures, and the most common measure of communication satisfaction were CAHPS items that specifically assess satisfaction with physician communication. Four of the findings indicated that black patients reported lower levels of satisfaction with patient-physician communication whereas three indicated that there was no difference between black and white patients’ ratings of satisfaction. Only one finding indicated that black patients reported higher satisfaction with patient-physician communication than white patients [45]. Specifically, this study found that black patients reported better communication than white patients on CAHPS items, which assess general satisfaction with the quality of physician communication. Among those findings examining the effect of racial concordance (n = 5) on patient-physician communication, most (n = 4) indicate that racial concordance is associated with higher levels of satisfaction with patient-physician communication, while one study found no effect of racial concordance on satisfaction [46].

Patients within primary care settings had the most mixed findings, with two studies indicating racial discordant patient-physician pairs had worse communication satisfaction ratings than white patients [9, 10], one study indicating that there was no significant difference between racially concordant versus discordant pairs [46], and a final study indicating black patients reported better communication satisfaction than white patients [45]. The majority of findings within cancer care settings, however, indicated there was no effect of race on satisfaction with communication with only one study indicating black patients had lower levels of satisfaction than white patients [32].

Information-Giving

The most commonly used measure among the observational studies assessing information-giving (n = 3) were coded interactions using the RIAS that assessed how many information-giving utterances the physicians made in which information was delivered to the patients (Table 4). For patients’ self-reported measures of information-giving (n = 3), the variables being measured were different. Patients self-reported the degree to which their physicians shared information [47], as well as satisfaction with information given and unmet information needs [38]. In five out of the six studies examining information-giving (which included both observational and patient reported measures of communication), physicians gave less information to black patients than to white patients. Two studies, however, found no statistically significant difference of information giving between black and white patients. Both of these studies included observational measures of communication. One study examined the effect of racial concordance on information-giving [47] and found that patients in black discordant and white discordant visits perceived (as rated via self-report) their physicians as sharing less information compared to patients in concordant visits.

The largest number of studies examining the effects of race and racial concordance on information giving occurred within cancer care settings. All of these studies found that information giving occurred less frequently among black patients compared to white patients [38, 47, 48]. The one study examining patients with HIV/AIDS settings showed no significant association between race and information-giving [18].

Partnership Building

Both observational studies assessing partnership building used the RIAS to code for total partnership building, initiated partnership building, and prompted partnership building whereas the patient-reported measure of partnership building assesses patients’ perceptions of the degree to which their physicians engaged in partnership building (Table 5). Although the two observational findings in this domain found no significant differences by race, one study that used patients’ self-report found that black patients reported their physicians as being less engaged in partnership building than white patients [47]. The same study also examined the effect of racial concordance on partnership building and found less perceived partnership building in discordant visits than in concordant visits. Partnership building studies occurred across a variety of settings (heart disease, cancer, and hypertension); thus, we were unable to examine differences in partnership building according to specialty.

Patient Participation and Participatory Decision-Making

There were a total of four studies in which patient participation or participatory decision-making were assessed as communication outcomes. Patient participation was only assessed through observational measures (n = 3), which exclusively used the RIAS to code for the presence of total participation and initiated patient participation (Table 6). Participatory decision-making was measured in another study that used patients’ perception of their physicians as participatory [10]. Two of the three studies found that black patients had fewer acts of patient participation, were less active participants, and had lower overall initiated patient participation than white patients [20, 47]. One study found no statistically significant differences between black and white patients in patient participation as measured by the RIAS [18]. The one finding examining the effect of racial concordance on participatory decision-making found that patients in race-concordant visits rated their physicians as more participatory than did patients in race-discordant visits [10].

Similar to partnership building, the four patient participation studies occurred across a variety of specialty settings (HIV/AIDS, cancer, heart disease, and primary care); thus, we were again unable to analyze differences between race and partnership building according to specialty. Of note, however, there was no significant association between race and patient participation among the HIV/AIDS patient population [18] whereas black patients in cancer and primary care settings had less patient participation and participatory decision-making than white patients and that racial concordance was associated with more participatory decision-making [10, 21], which is consistent with findings for other communication outcomes.

Positive and Negative Affect/Talk

Positive and negative affect/talk was assessed in observational studies which used the RIAS to code for physicians’ affective tone (positive and negative) in clinical interactions with patients (Table 7). Across the five observational findings reporting the effect of race on positive affect and positive talk, the majority found no difference between black and white patients on physicians’ positive affect and positive talk scores. Only one finding indicated that physicians’ affective tone was coded as less positive during medical visits with black patients than with white patients [23]. The one study examining the effect of racial concordance on positive talk found that racial concordance had no significant effect on physicians’ positive talk [25].

Findings are less clear in regards to the observational findings reporting the effect of race on negative talk. One study indicated that physicians were more contentious with black patients compared to white patients [25] whereas the other study found no difference between black and white patients on physician’s negative affective tone [24].

Only one study occurred in the context of HIV/AIDS, but once again showed that race had no effect on the positive and affect outcome [18]. In primary care settings, however, physicians’ affect was less positive during visits with black patients than white patients [23, 25].

Length of Visit/Time and Talk-Time Ratio

Length of visit was assessed in observational studies by examining the length of time (in minutes) of the visit, mean word count of the visit, or total number of utterances in the visit (Table 8). Results for the effect of race on length of visit/time spent with patients are again somewhat mixed. Nearly half of the findings (n = 4) reported that visits with black patients are significantly shorter or have lower word count than those with white patients. However, an additional four findings indicated that there were no significant differences between the length of visits nor the word count of visits with black patients compared with white patients. Only one finding [34] indicated that visits with black patients were longer than visits with white patients when time spent with patients was measured as the communication measure. The one study examining the effect of racial concordance found that race-concordant visits were longer (by approximately 2.2 min) than race-discordant visits [10].

Talk-time ratio was assessed using the RIAS to code for the utterances of patients and/or physician verbal dominance in clinical encounters. Findings were also mixed regarding the effect of race on the patient-physician talk-time ratio. Half of the findings (n = 2) indicated that physicians were more verbally dominant with black than with white patients [23, 33] whereas the other half (n = 2) of the findings indicate that there was no difference in provider statements or physician verbal dominance by race [18, 31].

Among patients in HIV/AIDS settings, one study found that black patients had less talk time/visit length than white patients [49] while one showed no significant difference between white and black patients on talk time/visit length [18]. Primary care settings had mixed results, with two studies showing racial concordance and being white (versus black) were associated with longer visits [10, 34], one study showing no statistically significant difference between black and white patients [23], and one study indicating that encounters with black patients were longer than those of white patients [34]. For the two studies which took place in cancer care settings, both studies indicated that black patients had shorter visits than white patients [21, 26].

Observational and Patient-Reported Findings of “Other” Communication Measures

Two remaining findings reported the effects of race and racial concordance on question asking and non-verbal behaviors (Table 9). In both of these studies, black patients had poorer observed communication compared to whites. Namely, one finding [50] indicated that black patients asked fewer total questions than white patients and another finding [51] indicated that white physicians had less eye contact with black patients than with white patients. Racial concordance was also associated with better non-verbal behaviors across black and white physicians and patients [51].

The majority of findings for the other categories of patient reported measures of patient-physician communication indicated that black patients reported poorer communication than white patients (Table 9). Specifically, white patients perceived significantly more attentiveness from physicians than black patients [52], black patients reported their physicians being less supportive compared to white patients [47], the odds of white patients reporting being treated with dignity and respect was higher than for black patients [36], and black patients reported significantly more interpersonal communication barriers [38]. Only one domain indicated that black patients had better communication outcomes than white patients. Namely, black patients were significantly less likely to report their physicians having poor cultural competency in communicating with them than white patients [53]. No significant differences were found between black and white patients on health promotion communication [53] or empathic communication [37]. Finally, racially discordant visits were perceived as less supportive compared to racially concordant visits [47] and patients were more likely to report respect with racially concordant physicians [36].

Discussion

Results from this systematic review demonstrate that the association between patient race (black or white) and patient-physician communication varies across studies, but the majority of the studies support the finding that black patients report poorer patient-physician communication than white patients. Namely, 38 out of 66 results from analyses show that black patients report lower patient-physician communication quality and satisfaction; less information-giving, partnership building, participatory decision-making, and positive talk; more negative talk; shorter visits; physicians who were more verbally dominant; and worse outcomes on non-verbal communication, respect, and support. In contrast, seven findings show that black patients have better communication with physicians than white patients. The additional 21 findings indicate no significant effect of race on communication. Considered together, these findings suggest that in most cases black patients report worse patient-physician communication than white patients, and occasionally race has no impact. Much less frequently, black patients report better patient-physician communication than white patients.

The results of the impact of clinical setting on patient-physician communication are somewhat mixed, in large part due to the variety of patient settings included in the review (HIV/AIDs, oncology, primary care, etc.) for each communication variable. One fairly consistent finding is the lack of a significant effect of race or racial concordance on communication in HIV/AIDS settings. This finding could be due, in part, to the nature of HIV/AIDS. HIV/AIDS is often heavily stigmatized, which may require its specialists to be more sensitive to biased communication toward patients. The paucity of research in this area and the mixed findings in the present systematic review call for further research to understand how race may differentially effect communication outcomes according to physician specialty and/or clinical setting.

Generally, findings for the effect of race on patient-physician communication are most consistent in demonstrating worse communication in the domains of observed communication quality, information-giving, and participatory decision-making. Findings are somewhat more mixed for patient-reported measures of communication quality, satisfaction, partnership building, positive talk, negative talk, length of visit, and talk-time ratio. One reason for inconsistency in study results may be the variability of communication measures across studies. These differences seem to be related to the measures assessed. For example, most studies assessing CAHPS or general satisfaction indicate that black patients have lower reported levels of satisfaction [32, 38, 54, 55] whereas two of the three studies which found no significant differences between racial groups use investigator-created measures of satisfaction [56, 57]. Because many studies use their own, investigator-developed measures to assess patient-physician communication domains such as quality [14, 16], satisfaction [9, 56], and partnership building [47], the variability of measures across studies is high.

In contrast, the studies on racial concordance tell a more consistent story. Specifically, racial discordance almost always predicted poorer communication (11 out of 12 studies) in the communication domains of satisfaction, information-giving, partnership building, participatory decision-making, visit length, and supportiveness and respect of conversations. The only communication domain in which racial concordance seemingly has no effect is in quality of communication, with all studies finding no effect of racial concordance on quality of communication. This finding may be due, in part, to the broadness of this category as assessing the general patient-centeredness of communication and patients’ perception that the communication was viewed positively or as “good.” As such, it may be less sensitive to differences according to racial concordance.

It is surprising that the studies reviewed here did not indicate a stronger association between racial concordance and communication quality, given the fact that minority patients prefer and report better medical outcomes with racially concordant visits [9]. One possible explanation for this finding is that many of the included studies measured racial concordance using patient surveys. Additional research in racial concordance using observational research may help us understand the relationship between racial concordance and patient-physician communication more clearly. This lack of a significant effect may also be due, in part, to the wide variability of measures of communication quality. However, it may also be that racial concordance between patients and physicians does not play a critical role in determining the quality of communication in these clinical interactions.

The inconsistency of measurements used in these studies may have also added to the variation of association between race and communication outcomes. Even when measures are consistent across studies, such as studies using the RIAS coding system, the categories of this coding system selected vary across studies. For instance, in assessing the quality of patient-physician communication, studies using the RIAS vary from measuring biomedical and psychosocial exchange to the patient-centered quality of interactions [23, 31]. As such, one conclusion from our systematic review of the extant literature is the need for more uniformity in measuring patient-physician communication to improve interpretability of the systematic review of these results. Part of the difficulty in assessing patient-physician communication, however, is that communication is a broad concept that covers several facets of communication occurring within a single patient-physician encounter. Another potential contributor to the lack of consistent measurement may be the scarcity of theoretical frameworks within the communication literature to guide how communication variables relate to outcomes of interest [58]. This lack of theory-driven research may contribute to inconsistency in both measurement and in interpreting results of communication studies across the literature. As such, future research could benefit from not only more consistent measurement of communication but more theory-driven models of the effect of race on communication outcomes.

The clarity and consistency of findings is seemingly related to not only the format of the measurement (observational versus patient-reported) but the specificity of the measure as well. For instance, six of the seven observational studies assessing patient-physician communication quality indicate that black patients had consistently lower quality of communication than white patients, regardless of the measure used to assess quality of communication. When examining patient-reported measures of quality of patient-physician communication, however, the level of specificity of the communication measures matters. For example, of those studies in which black patients report better quality of patient-physician communication than white patients, the measurement tools assess broader categories of overall satisfaction and shared goal setting [16]. Alternatively, when more specific measures of quality of communication are assessed—such as interpersonal exchange, fairness, and respect—black patients tend to report worse patient-physician communication quality than white patients. Thus, black patients may perceive physicians as having overall better quality of communication than white patients but perceive specific communication tactics as poorer.

Collectively, the included studies suggest racial concordance is a consistent predictor of better patient-physician communication with the exception of communication quality and that black patients tend to have both poorer observed communication and worse self-reported perceptions of patient-physician communication than white patients. Despite the preliminary insight this review provides, it does not conclusively support an overarching hypothesis that patient-physician communication is worse for black patients than white patients. More consistent measures of patient-physician communication are needed in order to clarify systematic results of studies examining the effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication.

In providing this analysis, we do not mean to place blame for poor communication on any one party. Healthcare communication is a transactional process, often with multiple parties involved, that is contextualized within multiple social contexts [59]. It is most likely that several explanations account for the overall, general negative findings from this review that black patients, or patients in non-concordant pairs, are more likely to have worse communication. These may include both the role of the physician and the role of the patient. In reference to the physician’s role, communication differences may be reflective of physicians’ biases and prejudices. Alternatively, the physician may be responding to differences in expressed patient preferences for shared decision-making and involvement. In reference to the patient’s role, a patient’s own communication and attitudes toward the physician and medical profession may influence a physician’s communication. Patients’ ability and desire to communicate with physicians and participate in communication skills training may also influence communication outcomes.

Each of these explanations is supported by research. For example, one study shows that physicians rate their coronary artery disease (CAD) black patients as higher risk for many factors, such as noncompliance with cardiac rehabilitation and substance abuse. Additionally, physicians rate black patients to be less educated and less intelligent, even when controlling for patients’ actual income and education [60]. Unconscious or implicit biases can also affect clinical judgments and decision-making [61]. These biases and prejudices can be directly observed in medical care, such as differences in mammogram screening recommendations [62].

On the patient side, well-documented mistrust among the black community with physicians and the medical field may be manifested in physician-patient communication through patient reticence and lack of questions, which physicians may in turn interpret as passivity or low intelligence, thus exacerbating the disparity [63]. As Gordon and colleagues (2005) put [20], these two factors can combine where “a scenario may unfold where physicians may be less engaged with African American patients, and the patient does little to prompt more from the doctor” (p. 1022). In addition to holding their own biases, patients may also lack the training or skillset to understand how to communicate most effectively with their physicians. This, in turn, is why much of the health disparities literature focuses on models of patient navigation in which patients are given navigators to help them navigate medical systems [64, 65]. This could be extended toward helping patients navigate their own communication with physicians by training them in how to communicate most effectively.

Summarizing these results highlights that both physicians and patients may benefit from training to improve communication. Street and colleagues [66] argue that physicians can overcome the barriers inherent in racially discordant interactions through training, arguing that “a physician who is skilled in informing, showing respect, and supporting patient involvement can transcend issues of race and sex to establish a connection with the patient that in turn contribute to greater patient satisfaction, trust and commitment to treatment” (p. 203). Developing competent, patient-centered communication begins in medical school with a strong curriculum, practice, and feedback, and continues with feedback and coaching throughout individuals’ graduate training and beyond.

Patients can also benefit from communication skills training and development. For instance, interventions to train patients in “consultation planning” by focusing on how to best communicate in their consultations with physicians lead to improvements in both patients’ and physicians’ satisfaction with consultation and reductions in barriers to communication [67]. The PACE system, developed by Don Cegala and colleagues [68], is also used widely as an intervention to improve patient skills such as Presenting Information, Asking Questions, Checking Understanding, and Expressing Concerns. However, further research is needed to examine the effectiveness of communication skills training for patients who are from non-white backgrounds. A prior set of studies by Cegala and colleagues found that patient communication skills training were less effective among non-white patients than among white patients [69]. Thus, further research is warranted to address if and how interventions tailored to non-white patients can help to address racial disparities in patient-physician communication.

There are limitations to the body of research reviewed here that should be considered when interpreting results. First, as noted, most of the articles vary in their assessments of the domains of patient-physician communication assessed. As such, there is much variability and a lack of consistency in measures used across the studies. To address this limitation, future work should aim to conduct more rigorous research using validated and consistent measures of communication to examine the effect of race on patient-physician communication. This will greatly improve future research and allow for a more systematic analysis of the data. Additionally, as noted earlier, utilizing theoretical frameworks to guide communication research may also improve the consistency and reliability of measures (and results, accordingly) of communication across studies [58].

Another limitation of the body of research reviewed here is that observational and patient-reported measures are rarely assessed within the same study, making it difficult to interpret whether patients’ perceptions differ from researchers’ observations of the encounters. Future research could aim to include both measures of communication into single studies to compare the effects of race on observed versus perceived differences in patient-physician communication. Additionally, most of the literature reviewed here assesses either observational measures of a single encounter or patients’ perceptions of communication quality in a single encounter. However, patients may have rated their physicians’ communication based on a long-standing relationship rather than a single encounter as indicated in study procedures. Future research should focus more on examining the effect of race on patient-physician communication among new patients versus patients with longer relationships with their physicians to disentangle these potential effects. Finally, it is likely that the positive findings reviewed here are overstated due to publication bias. As such, these results should be interpreted with some caution.

Despite the limitations of the studies reviewed, some insight can be gained from the results summarized. Namely, results are more likely to be consistent and to demonstrate that black patients experienced poorer communication than white patients when using validated measures of communication such as the RIAS [39] or the CAHPS [30] rather than investigator-created measures. More broadly, this systematic review highlights that, in most cases, race does matter in regards to patient-physician communication. As noted in this review, recent research indicates that race does influence communication between patients and physicians and this influence could have a larger effect on health disparities. The present systematic review lays the foundation to inform future work that could examine how racial communication disparities and racial concordance/discordance between patients and physicians influence patients’ health outcomes. This could ultimately help inform and reduce disparities in black-white health outcomes.

This review also provides a foundation for future work by highlighting the need for more consistent measures of patient-physician communication in the literature. As noted, there is a need to define and more consistently measure communication in order to provide a clearer picture of the effect of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication. Additionally, future work is needed to better determine the causes of racial influence on patient-physician communication. To date, most studies rely on race as a self-defined identity or construct. However, future work is needed to disentangle the role of race from a person’s identification with their race. It is possible that other more socially constructed features of race, such as the level of identity one has with his or her racial group, influence perceptions of communication. Moreover, other features such as dress and language that is consistent with one’s racial group may also influence physicians’ communication with patients. By more clearly measuring and examining these features of race and how they relate to communication, we can also begin to gain clearer insight into why race is often associated with worse communication outcomes but why it also varies across studies. As the research in this area becomes more rigorous and sophisticated, it is our hope that a clearer picture will emerge of the relationship between race and patient-physician communication and that this form of communication will be targeted for improvements and reductions in health disparities.

References

Institute of Medicine, Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. 2003: Washington DC.

Kahn KL, et al. Health care for black and poor hospitalized Medicare patients. JAMA. 1994;271(15):1169–74.

Fiscella K, et al. Inequality in quality: addressing socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic disparities in health care. JAMA. 2000;283(19):2579–84.

Fennell ML. Racial disparities in care: looking beyond the clinical encounter. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1713–21.

National Center for Health Statistics. Available from: www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lcod.htm.

Saha S, et al. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997–1004.

Mayberry RM, Mili F, Ofili E. Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(4 suppl):108–45.

Smedley, B.D., A.Y. Stith, and A.R. Nelson, Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care (full printed version). 2002: National Academies Press.

Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(3):296–306.

Cooper LA, et al. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–15.

Sweeney CF, et al. Race/ethnicity and health care communication: does patient-provider concordance matter? Med Care. 2016;54(11):1005–9.

Penner LA, et al. Life-threatening disparities: the treatment of black and white cancer patients. J Soc Issues. 2012;68(2):328–57.

Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1995;152(9):1423.

Street Jr RL, Gordon H, Haidet P. Physicians’ communication and perceptions of patients: is it how they look, how they talk, or is it just the doctor? Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(3):586–98.

Ghods BK, et al. Patient-physician communication in the primary care visits of African Americans and whites with depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):600–6.

Alexander J, Hearld L, Mittler JN. Patient-physician role relationships and patient activation: the moderating effects of race and ethnicity. Med Care Res Rev. 2014;71(5):472–95.

Ayanian JZ, et al. Patients’ experiences with care for lung cancer and colorectal cancer: findings from the cancer care outcomes research and surveillance consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4154–61.

Beach MC, et al. Patient-provider communication differs for black compared to white HIV-infected patients. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(4):805–11.

Leyva, B., et al., Do men receive information required for shared decision making about PSA testing? Results from a national survey. Journal of Cancer Education, 2015.

Gordon HS, et al. Physician-patient communication following invasive procedures: an analysis of post-angiogram consultations. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(5):1015–25.

Gordon HS, et al. Racial differences in doctors’ information-giving and patients’ participation. Cancer. 2006;107(6):1313–20.

Beach M, et al. Patient-provider communication differs for black compared to white HIV-infected patients. AIDS & Behavior. 2011;15(4):805–11.

Johnson RL, et al. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2084–90.

Street Jr RL, et al. Affective tone in medical encounters and its relationship with treatment adherence in a multiethnic cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2015;21(4):181–8.

Street RL, Gordon H, Haidet P. Physicians’ communication and perceptions of patients: is it how they look, how they talk, or is it just the doctor? Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(3):586–98.

Eggly, S., et al., A disparity of words: racial differences in oncologist-patient communication about clinical trials. Health Expect, 2013.

Ong LM, et al. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(7):903–18.

Meghani SH, et al. Patient–provider race-concordance: does it matter in improving minority patients’ health outcomes? Ethn Health. 2009;14(1):107–30.

Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Hays RD, et al. Psychometric properties of the CAHPS™ 1.0 survey measures. Med Care. 1999;37(3):MS22–31.

Hausmann LR, et al. Orthopedic communication about osteoarthritis treatment: does patient race matter? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(5):635–42.

Levinson W, et al. “It’s not what you say … ”: racial disparities in communication between orthopedic surgeons and patients. Med Care. 2008;46(4):410–6.

Martin KD, et al. Physician communication behaviors and trust among black and white patients with hypertension. Med Care. 2013;51(2):151–7.

Oliver MN, et al. Time use in clinical encounters: are African-American patients treated differently? J Natl Med Assoc. 2001;93(10):380–5.

Keller AO, Gangnon R, Witt WP. Favorable ratings of providers’ communication behaviors among U.S. women with depression: a population-based study applying the behavioral model of health services use. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23(5):e309–17.

Malat J. Social distance and patients’ rating of healthcare providers. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42(4):360–72.

Taira DA, et al. Do patient assessments of primary care differ by patient ethnicity? Health Serv Res. 2001;36(6 Pt 1):1059–71.

Manfredi C, et al. Are racial differences in patient-physician cancer communication and information explained by background, predisposing, and enabling factors? J Health Commun. 2010;15(3):272–92.

Roter D, Larson S. The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS): utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46(4):243–51.

Stewart AL, et al. Interpersonal processes of care survey: patient-reported measures for diverse groups. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(3 I):1235–56.

Schnittker J, Liang K. The promise and limits of racial/ethnic concordance in physician-patient interaction. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2006;31(4):811–38.

Jerant A, et al. Patient-provider sex and race/ethnicity concordance: a national study of healthcare and outcomes. Med Care. 2011;49(11):1012–20.

Korthuis PT, et al. Impact of patient race on patient experiences of access and communication in HIV care. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):2046–52.

Sweeney, C.F., et al., Race/ethnicity and health care communication: does patient-provider concordance matter? Med Care, 2016.

Fongwa MN, et al. Reports and ratings of care: black and white Medicare enrollees. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(4):1136–47.

Gupta N, Carr NT. Understanding the patient-physician interaction potential for reducing health disparities. J Appl Soc Sci. 2008;2(2):54–65.

Gordon HS, et al. Racial differences in trust and lung cancer patients’ perceptions of physician communication. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):904–9.

Gordon HS, et al. Racial differences in doctors’ information-giving and patients’ participation. Cancer. 2006;107(6):1313–20.

Laws MB, et al. The association of visit length and measures of patient-centered communication in HIV care: a mixed methods study. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(3):e183–8.

Eggly S, et al. Variation in question asking during cancer clinical interactions: a potential source of disparities in access to information. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(1):63–8.

Stepanikova I, et al. Non-verbal communication between primary care physicians and older patients: how does race matter? J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5):576–81.

Basanez T, et al. Ethnic groups’ perception of physicians’ attentiveness: implications for health and obesity. Psychol Health Med. 2013;18(1):37–46.

Seligman HK, et al. Risk factors for reporting poor cultural competency among patients with diabetes in safety net clinics. Med Care. 2012;50(9 SUPPL. 2):S56–61.

Paddison CAM, et al. Experiences of care among Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD: Medicare consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems (CAHPS) survey results. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(3):440–1.

Zickmund SL, et al. Racial differences in satisfaction with VA health care: a mixed methods pilot study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(3):317–29.

Palmer NR, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in patient-provider communication, quality-of-care ratings, and patient activation among long-term cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(36):4087–94.

Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Cooper LA. Patient-physician relationships and racial disparities in the quality of health care. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1713–9.

Street RL, et al. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Counseling. 2009;74(3):295–301.

Street, RL Jr. Communication in medical encounters: an ecological perspective. In: Thompson TL, Alicia M. Dorsey, Katherine I. Miller, Roxanne Parrott, editors. Handbook of health communication. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003.

Van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(6):813–28.

Green AR, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1231–8.

Bao Y, Fox SA, Escarce JJ. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic differences in the discussion of cancer screening:“between-” versus “within-” physician difference. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(3):950–70.

Freimuth VS, et al. African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee syphilis study. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(5):797–808.

Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: current practices and approaches. Cancer. 2005;104(4):848–55.

Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science (review). CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(4):237–49.

Street RL, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(3):198–205.

Sepucha KR, et al. Consultation planning to help breast cancer patients prepare for medical consultations: effect on communication and satisfaction for patients and physicians. Journal of Clinial Oncology. 2002;20(11):2695–700.

Cegala DJ. Communicating with your doctor: the PACE system. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University; 2000.

Cegala DJ, Post DM. On addressing racial and ethnic health disparities the potential role of patient communication skills interventions. Am Behav Sci. 2006;49(6):853–67.

Smith AK, Davis RB, Krakauer EL. Differences in the quality of the patient-physician relationship among terminally ill African-American and white patients: impact on advance care planning and treatment preferences. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1579–82.

Saha S, et al. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997–1004.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report and have conducted this study following all required ethical standards and with proper IRB consent at participating institutions. No human research subjects were directly involved in this study as it was a systematic review of the literature, thus informed consent was not required.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (T32-CA009461 and P30-CA008748). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, M.J., Peterson, E.B., Costas-Muñiz, R. et al. The Effects of Race and Racial Concordance on Patient-Physician Communication: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 5, 117–140 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4