Abstract

Clinical decision-making may have a role in racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare but has not been evaluated systematically. The purpose of this study was to synthesize qualitative studies that explore various aspects of how a patient’s African-American race or Hispanic ethnicity may factor into physician clinical decision-making. Using Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Library, we identified 13 manuscripts that met inclusion criteria of usage of qualitative methods; addressed US physician clinical decision-making factors when caring for African-American, Hispanic, or Caucasian patients; and published between 2000 and 2017. We derived six fundamental themes that detail the role of patient race and ethnicity on physician decision-making, including importance of race, patient-level issues, system-level issues, bias and racism, patient values, and communication. In conclusion, a non-hierarchical system of intertwining themes influenced clinical decision-making among racial and ethnic minority patients. Future study should systematically intervene upon each theme in order to promote equitable clinical decision-making among diverse racial/ethnic patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The clinical decision-making process is complex [1, 2]. Guidelines exist to help clinicians make evidence-based decisions [3, 4]. Although there are clinical scenarios in which clinical decision-making should be clear (e.g., Class I guideline indication or Class III guideline indication), there are many areas of medicine that do not fall into clear decision categories and are much more vague. Race or ethnicity is rarely an indication for change in clinical care. Yet, notable differences in clinical decision-making process exist among racial or ethnic minority patients [3, 5].

Understanding differences in provider clinical decision-making by race and ethnicity is a necessary first step in creating equity in healthcare. Multiple studies of healthcare providers have demonstrated negative implicit bias towards racial and ethnic-minority patients, particularly African-Americans and Hispanics [6,7,8,9], and some have concluded that racial or ethnic bias may contribute to health disparities [10, 11]. However, other studies suggest that a negative bias towards minorities is not associated with inequitable decision-making [12, 13]. Several qualitative studies have explored the relationship between physician decision-making and patient race or ethnicity [14, 15], but there has been no robust synthesis of qualitative studies of physician decision-making across race and ethnicity.

A qualitative meta-synthesis is an ideal approach for critically evaluating qualitative data that explore physician clinical decision-making. Thus, the objective of this study was to rigorously evaluate and synthesize qualitative studies that explore factors related to contemporary physician clinical decision-making for African-American and Hispanic patients over the past two decades. Increasing awareness and understanding of the clinical decision-making process will contribute to the design and evaluation of future interventions that aim to create equity in healthcare.

Methods

This study used the Enhanced Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) to understand physician approaches to clinical decision-making among racial/ethnic minorities [16]. A systematic literature search was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) [17]. The Letts Criteria was performed for quality appraisal of qualitative studies [18]. The Thomas and Harden approach was used for thematic synthesis [19].

Search Strategy

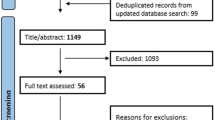

Inclusion criteria for this meta-synthesis included contemporary qualitative studies, published in 2000 or later, which address physician perceptions of providing clinical care to African-American or Hispanic patients in the USA. Studies were excluded if they were non-qualitative studies, focused on other races/ethnicities, or focused only on patient rather than physician perceptions. When a manuscript included a combination of physician, nurse, medical student, and patient perspectives, only physician results were included for analysis. A professional librarian (L.H.) searched Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Library to identify qualitative studies addressing the factors related to physician clinical decision-making for African-Americans and Hispanics. We limited the search to US studies with an emphasis on African-American or Hispanic patients since they represent the largest racial and ethnic groups in the USA and have the highest proportion of healthcare disparities [20]. The search strategy for each database included the following concepts: physicians, ethnicity, healthcare treatment, and qualitative studies. Multiple subject headings and text word terms were included to describe these concepts. The search was limited to English-language studies, and the years 2000 to present, in order to address contemporary care. The search is complete through April 3, 2017. The PRISMA search strategy is in the Supplement (Supplemental Tables Search Strategy) [17]. All manuscript titles and abstracts identified in the initial search were reviewed for inclusion criteria by the primary investigator (K.B.) (Figure). An additional manuscript was identified outside of the professional librarian search using Google search and was added to this study.

Quality Appraisal

The Letts “Guidelines for Critical Review Form: Qualitative Studies” provides one of the most comprehensive appraisals of qualitative studies [18]. Letts Criteria has precision in the assessment of rigor through (1) credibility: trustworthiness of the analysis, (2) transferability: generalizability, (3) dependability: consistency of data often achieved with an audit trail, and (4) confirmability: bias reduction of the researcher by seeking external opinions of the data [18]. All manuscripts meeting inclusion criteria were appraised with the Letts Criteria by the primary investigator (K.B.), and a random sample was reappraised by study team member (D.K.) for efficacy (Table 1). Manuscripts were evaluated and reported across eight key domains: study purpose, literature, study design, sampling, data collection, data analyses, overall rigor, and conclusions/implications [18]. All manuscripts met most Letts criteria and were deemed appropriate for inclusion. However, most studies did not evaluate for saturation of themes due to limits in reaching target number of racial and ethnic minority participants. The majority of the studies were also lacking researcher relationship to participants and researcher assumptions and biases. Although many studies were missing transferability and dependability, overall rigor was appropriately met for the majority of studies through analytic rigor, credibility, and confirmability.

Meta-Synthesis

Meta-synthesis has an interpretative rather than aggregating intent, in contrast to meta-analysis of quantitative studies [32]. Qualitative data are useful for providing a snapshot of one person’s interpretation of an event or phenomenon. By bringing together many different interpretations, conclusions are strengthened by discovering common themes and differences, and by building new interpretations of the topic of interest [32]. Thus, a thematic synthesis was used based upon the Thomas and Harden approach [19]. Manuscripts were summarized with study aim, study design, methods, participant descriptions, and summary of findings by the primary investigator (K.B.) (Table 2). All primary quotes from each manuscript underwent iterative line-by-line coding for thematic analysis with an inductive approach by the primary investigator (K.B.) and study team (H.L., D.K.). Theory was derived from the data rather than pre-existing theories being applied to the data. Additional iterations were characterized into derived themes and subthemes over the course of several weeks. Concordance was achieved through majority agreement of the study team. Credibility and confirmability were obtained through triangulation with the initial study team (K.B., J.J., H.L., D.K., USA) and expert co-authors. An audit trail of theme derivations was maintained throughout the study. The final derived themes exhibited overlap but were further characterized by exemplar quotes and written description (Table 3). Exemplar quotes best displayed the derived themes and subthemes. The physician’s self-identified race and ethnicity, sex, and city of practice were included when available to provide further insight into quotes.

Results

Among 579 manuscripts identified with the initial search strategy, 86 were duplicates. The primary investigator (K.B.) reviewed 493 manuscript titles and abstracts for inclusion criteria; 481 manuscripts were excluded (patient perceptions only n = 186, review n = 23, non-USA study n = 78, non-qualitative study n = 143, not involve race n = 4, off topic n = 40, non-physician n = 3, other race and ethnicity n = 4). An additional manuscript not found during the professional search was identified during literature search and added for a final total of 13 manuscripts representing 518 physicians (Fig. 1, [14, 15, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]).

Among the final 13 manuscripts, 6 derived themes addressed factors related to physician clinical decision-making for African-American and Hispanic patients. Derived themes included the importance of race, patient-level issues, system-level issues, bias and racism, patient values, and communication (Table 3). The themes were further characterized by 18 subthemes exploring reasons for differential clinical decision-making among African-American and Hispanic patients. The themes were not hierarchical in relationship but rather an interrelated system of themes that appeared to potentiate each other (Fig. 2).

Importance of Race

Physicians had different perspectives on the importance of race in clinical decision-making. There was support and disapproval for explicitly using race in clinical decision-making. Subthemes included discomfort discussing race with patients, differing opinions regarding the definition of race, affirmation that race matters in medicine and should be used to guide decision-making, and believing that genetics may improve care of racial and ethnic minorities. However, physician perspectives differed by physician race.

A Caucasian physician described difficulty in using race to make clinical decisions since this physician was unclear of the appropriate way to define race.

Plus there’s no certain line about what race is. I mean what percentage of a particular race do you have to be to be that race. Do you have a reflectometer to measure the skin color? What does it mean? (Baltimore, Caucasian) (Reference 1 page 4, 1p4).

An African-American physician described that race matters but chose not to describe race in clinical settings due to the potential improper treatment of patients based upon labeling of race and ethnicity.

... but I think that there are some real historical implications of race as it relates to health status of African-Americans. The issue of race was used to separate African-Americans and European Americans on wards. Your race identified where you would go, and what level of care you received...One of the reasons I don’t take race is because historically, I have a huge problem with how it has been used. And, I’m not sure what that marker will mean in, as I put it on the chart as it, as that chart flies through here and there. (Detroit, African-American) (1p5).

Patient-Level Issues

Physicians attributed racial and ethnic differences in clinical decision-making to common patient-level issues that were assumed to be associated with race. Subthemes included addressing barriers of accessibility like insurance, patient liability for outcomes, patient demands varying by race and ethnicity, immigrant status changing the ability to provide clinical care, and multiple comorbidities of racial and ethnic minorities impacting patient outcomes.

One Caucasian physician shared how she had not sent her racial/ethnic minority patients to see specialists when indicated because the patients were underinsured.

So it’s really hard to get a lot of specialists. And they will be upset if you refer someone that really doesn’t need to be referred to see medical assistance patients. Because they’re not going to get reimbursed for it at all. And they don’t want to be seeing something that the primary care provider could have taken care of. Whereas…someone who’s educated, working, has good insurance, they want…probably specialist because their insurance is going to pay for it. So that’s a disparity. (female, Caucasian) (3p393).

Another Caucasian physician described that racial/ethnic minority patients were less adherent to medical regimens. Therefore, she was less likely to send her patients to specialists.

…if a physician feels the patient isn’t very compliant with the regimen they’ve recommended, then they might be less likely to send them to a specialist…if they’re not even following up with the treatment I recommend, why bother to send them to another physician, who’s going to recommend, to evaluate this problem when they’re not even taking care of their hypertension in the first place? (female, Caucasian) (3p390).

System-Level Issues

Physicians described system-level issues that factored into the clinical decision-making process for racial and ethnic minority patients. Subthemes included site issues and physician knowledge issues related to caring for racial and ethnic minority patients.

In a clinic serving a predominantly minority population, physicians described inadequate support of the healthcare clinic and lack of guidelines as a reason for disparities in this population.

Insufficient primary care clinic infrastructure (personnel, space, data support etc) as a barrier (5p258).

No guidelines, or clinic policies concerning colorectal cancer in clinics as a barrier (5p258).

Bias and Racism

Physicians from both Caucasian and African-American races described bias and racism as reasons for differences in clinical decision-making of racial and ethnic minority patients. Specifically, they believed that minority patients were subject to negative bias and racism.

An African-American physician described an unconscious racism example he has witnessed from Caucasian physicians towards African-American patients.

…the physician is empathizing more for the White patient because he has more of a connection with him…Most doctors who are very good doctors, and otherwise nice people, are simply doing less for the Black patient because they have this unconscious racism. I guess it’s kind of hard to swallow, but you almost don’t want to accept it. (male, African-American) (3p393).

A Caucasian physician described an example of bias or racism towards African-American patients leading to differences in clinical care.

I’ve had ... [Black] patients who I think have not been offered procedures because of either where they were economically or where they were assumed to be economically because of their race... I had a patient who clearly needed to be catheterized for their presentation and it was suggested that we do medical management. And I remember talking to the cardiologist and just saying that I didn’t understand why we’re doing this ... As soon as we started talking, he said, ‘oh well, of course, we’ll cath him.’ And so, like that, it changed...[I] certainly have enough anecdotal experience to think that people are probably [being] treated differently based on race. (male, Caucasian) (11p5).

Patient Values

Physicians attribute differences in clinical decision-making to variable patient values demonstrated in racial and ethnic minority patients. Subthemes included lower levels of trust in the healthcare system among minority patients related to historical disservice, spiritual beliefs guiding minority patient decisions, and minorities’ fear of procedures.

Physicians below described positive and negative experiences discussing religion with their racial and ethnic minority patients.

Blacks tend to be, uh, very religious individuals and so, if you’re not a religious person yourself, if you really don't have that, the faith, and, really talk about God,—it’s hard to get their trust,—that’s why doctors who are not religious or don't show it may have it harder to gain black patients’ trust. (2p6).

The Hispanic physician groups had the most diverse responses to the question about religious beliefs, ranging from not mentioning faith or religion at all because it could be interpreted as ‘too intrusive’ to asking everyone about religious beliefs because they had experienced patients who 'stopped stressing out when you talk to them about God' and that it restored patients’ hope. (2p7).

Communication

Differences in communication were thought to contribute to differences in clinical decision-making for racial and ethnic minority patients. Subthemes included expressing willingness to understand a patient’s culture, communication through the patient’s language, and willingness to negotiate with the patient to achieve care goals.

One physician shared the importance of inquiring about the individual racial/ethnic minority patient’s culture in order to improve the physician-patient relationship.

I think the biggest one is to not be afraid of the fact that you’re going to hurt their feelings by asking them, ‘What cultural things do you think I should know about you to help me care for you better?’ (10p877).

A physician described how he maintained a relationship with his Hispanic patient by negotiating treatment with both guideline-based allopathic medicine and complementary alternative medicine.

I have a patient who is Hispanic who really doesn’t want to come to terms with his diagnosis of diabetes. He’s a young guy and he’s trying all kinds of herbs, and I had to put aside my scientific thinking to come to an agreement with him that he could do that as long as he also monitored his blood sugar. (10p878).

Discussion

In this meta-synthesis of contemporary qualitative studies, physicians from diverse backgrounds believed that a patient’s race and ethnicity factored into the clinical decision-making process for healthcare. We derived six key themes factoring into the clinical decision-making process, including importance of race, patient-level issues, system-level issues, bias and racism, patient values, and communication. Many of the subthemes implied negative perspectives towards racial and ethnic minorities. Overall, the themes were not hierarchical rather an interrelated system of issues that potentiate each other. This study moves the racial and ethnic disparities field forward by openly asking how race and ethnicity impact clinical decision-making. Compared to quantitative studies, this meta-synthesis was able to demonstrate the interrelated system of factors that contribute to racial and ethnic differences in care. This study provides an informed guide of factors that must be targeted in order to achieve equity in clinical decision-making among diverse racial and ethnic populations.

Our results support quantitative findings that suggest the physician clinical decision-making process is influenced by patient race and ethnicity [3, 33]. Clinical decisions are not being made on purely objective medical information [3, 33]. The Institute of Medicine’s Unequal Treatment Report identified variability in provider clinical decision-making based upon race and ethnicity, which resulted in healthcare disparities [34]. In a quantitative study of 164 medical students, when an African-American female patient and a Caucasian male patient actor both enacted the same symptoms of angina, medical students were more likely to believe that the Caucasian patient had true angina, especially when the medical students were also of Caucasian race [35]. Similarly in a quantitative survey study, 720 physicians randomized to clinical vignettes with patients of different races perceived known life-saving treatments to be less appropriate in racial minorities [36]. In another survey study, 284 nephrologists felt that renal transplants would be less effective in improving survival in African-Americans than in Caucasians and believed that African-Americans were offered transplants less often due to patient preferences rather than physician bias [37].

A multi-targeted approach is needed to reduce racial/ethnic differences in physician clinical decision-making. Both theoretical and evidence-based methods are available for each of the six derived themes of this meta-synthesis. First, there are differing viewpoints on the importance of race during a physician-patient interaction, including what race means and how it should be used. This can be addressed with physician cultural education during training and practicing years, which has been associated with improved patient outcomes [34, 38,39,40]. Cultural training includes training in perspective-taking, seeking common group identities, teaching skepticism with race-based differences in care, increasing awareness of structural racism and inequality [38, 41]. Second, patient-level issues related to socioeconomic position occur more frequently in racial/ethnic minorities [42, 43]. Usage of a social worker or community liaison has assisted with meeting patient-specific needs [40, 44,45,46,47]. Also, treating the patient as an individual rather than as a collective group of people may reduce racial/ethnic disparities in care [39, 48, 49]. Third, healthcare system-level issues must be addressed. Decreasing stressors that increase a physician’s cognitive load (i.e., large patient cohort, short period of time to see patients, dysfunctional computer system) and evaluating for systematic differences in healthcare delivery have been associated with more equitable care [48, 50]. Fourth, bias and racism exist from individual levels through societal infrastructure [48]. Multiple approaches associated with reduction in bias and racism in the patient-physician interaction include promoting intergroup relationships and egalitarian views [38, 50, 51], perspective shifting education that may alter bias [52], providing bias education and training [38, 49, 53], increasing objectivity through guidelines-based care [34, 50, 54], and an emerging method that implements reflective group decision-making [55]. Fifth, patient’s values should be considered. Similar to the approach for patient-level issues, each patient’s care should be individualized rather than generalized to racial/ethnic stereotypes [39, 48, 49]. Sixth, communication should be a focus for reducing racial/ethnic disparities. This requires an improved perspective on marginalized patient groups and willingness to identify ways to communicate in the patient’s language [38, 56]. In summary, because of the interrelated themes, eradicating a single factor or theme would not inhibit the system of racial/ethnic health inequality. Multiple simultaneous interventions are indicated for each theme.

Several limitations of this work should be considered. First, the primary data for each study were not accessible. Analyses are based upon the selected data that were published in each manuscript, which is an inherent limitation to meta-syntheses. However, most of the selected manuscripts included substantial quotes that would allow for consistent thematic assessment. Second, the clinical decision-making process for healthcare is a shared pathway between physicians and patients. The patient perspective is not provided in this meta-synthesis. We chose to focus on the clinician perspectives since numerous qualitative studies have evaluated the perspective of racial and ethnic minority patients. Third, most studies did not denote evaluation for saturation during thematic analysis nor did researchers identify relationships to participants. Although this may result in response bias, the consistency of themes across multiple studies suggests appropriate sampling and precise results. Lastly, this meta-synthesis focuses on African-American and Hispanic minority patients since they have well-documented health disparities [20]. Results may not be generalizable to other racial and ethnic minorities. However, approaches for providing equitable objective healthcare may be useful for all racial and ethnic groups and may extend to other intersections with race and ethnicity like sex, socioeconomic position, and creed.

Conclusion

In this qualitative meta-synthesis of physician perceptions, we found that physicians perceive that a patient’s race and ethnicity factored into the physician clinical decision-making process, predominantly in a negative way. Themes were non-hierarchical, interrelated, and potentiating. The themes included understanding the importance of race, patient-level issues, system-level issues, bias and racism, patient values, and communication. Future steps in developing health equity among racial and ethnic minority patients should include application of multi-targeted interventions for each factor simultaneously. A structured institutional strategy to implement new interventions will require buy-in from hospital administrators, healthcare providers, trainees, and community stakeholders.

References

Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.476.

Bate L, Hutchinson A, Underhill J, Maskrey N. How clinical decisions are made. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74(4):614–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04366.x.

Hajjaj F, Salek M, Basra M, Finlay A. Non-clinical influences on clinical decision-making: a major challenge to evidence-based practice. J R Soc Med. 2010;103(5):178–87. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2010.100104.

Ross JS. Promoting evidence-based high-value health care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1564. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3543.

Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1.

Blair IV, Steiner JF, Fairclough DL, Hanratty R, Price DW, Hirsh HK, et al. Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias and perceptions of care among black and Latino patients. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):43–52. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1442.

Sabin J, Nosek BA, Greenwald A, Rivara FP. Physicians’ implicit and explicit attitudes about race by MD race, ethnicity, and gender. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(3):896–913. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.0.0185.

Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, Beach MC, Sabin JA, Greenwald AG, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):979–87. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558.

Johnson TJ, Winger DG, Hickey RW, Switzer GE, Miller E, Nguyen MB, et al. A comparison of physician implicit racial bias towards adults versus children. Acad Pediatr. 2016;17(2):120–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.08.010.

Blair IV, Steiner JF, Havranek EP. Unconscious (implicit) bias and health disparities: where do we go from here? Perm J. 2011;15(2):71–8.

Balsa AI, McGuire TG. Prejudice, clinical uncertainty and stereotyping as sources of health disparities. J Health Econ. 2003;22(1):89–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00098-X.

Haider AH, Sexton J, Sriram N, Cooper LA, Efron DT, Swoboda S, et al. Association of unconscious race and social class bias with vignette-based clinical assessments by medical students. JAMA. 2011;306(9):942–51. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1248.

Haider AH, Schneider EB, Sriram N, Dossick DS, Scott VK, Swoboda SM, et al. Unconscious race and social class bias among acute care surgical clinicians and clinical treatment decisions. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(5):457–64. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2014.4038.

Plaisime MV, Malebranche DJ, Davis AL, Taylor JA. Healthcare providers’ formative experiences with race and black male patients in Urban Hospital environments. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;4(6):1120–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0317-x.

Snipes SA, Sellers SL, Tafawa AO, Cooper LA, Fields JC, Bonham VL. Is race medically relevant? A qualitative study of physicians’ attitudes about the role of race in treatment decision-making. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):183. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-183.

Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Letts L, Wilkins S, Law M, et al. Guidelines for critical review form: qualitative studies (version 2.0). McMaster University occupational therapy evidence-based practice research group. 2007 https://www.canchild.ca/system/tenon/assets/attachments/000/000/360/original/qualguide.pdf.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

Disparities in healthcare quality among racial and ethnic minority groups | AHRQ Archive. https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqrdr10/minority.html. Accessed 3 May 2017.

Bonham VL, Sellers SL, Gallagher TH, Frank D, Odunlami AO, Price EG, et al. Physicians’ attitudes towards race, genetics and clinical medicine. Genet Med Off J Am Coll Med Genet. 2009;11(4):279–86. https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e318195aaf4.

Braun UK, Ford ME, Beyth RJ, McCullough LB. The physician’s professional role in end-of-life decision making: voices of racially and ethnically diverse physicians. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(1):3–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.018.

Clark-Hitt R, Malat J, Burgess D, Friedemann-Sanchez G. Doctors’ and nurses’ explanations for racial disparities in medical treatment. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(1):386–400. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.0.0275.

Frank D, Gallagher TH, Sellers SL, Cooper LA, Price EG, Odunlami AO, et al. Primary care physicians’ attitudes regarding race-based therapies. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(5):384–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1190-7.

Goodman MJ, Ogdie A, Kanamori MJ, Cañar J, O’Malley AS. Barriers and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening among mid-Atlantic Latinos: focus group findings. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):255–61.

Johansson P, Jones DE, Watkins CC, Haisfield-Wolfe ME, Gaston-Johansson F. Physicians’ and nurses’ experiences of the influence of race and ethnicity on the quality of healthcare provided to minority patients, and on their own professional careers. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2011;22(1):43–56.

Mott-Coles S. Patients’ cultural beliefs in patient-provider communication with African American women and Latinas diagnosed with breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(4):443–8. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.CJON.443-448.

Nunez-Smith M, Curry LA, Berg D, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH. Healthcare workplace conversations on race and the perspectives of physicians of African descent. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1471–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0709-7.

Owsley C, McGwin G, Scilley K, Girkin CA, Phillips JM, Searcey K. Perceived barriers to care and attitudes about vision and eye care: focus groups with older African Americans and eye care providers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(7):2797–802. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.06-0107.

Park ER, Betancourt JR, Kim MK, Maina AW, Blumenthal D, Weissman JS. Mixed messages: residents’ experiences learning cross-cultural care. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2005;80(9):874–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200509000-00019.

Ward SH, Parameswaran L, Bass SB, Paranjape A, Gordon TF, Ruzek SB. Resident physicians’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to colorectal cancer screening for African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(4):303–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30602-7.

Walsh D, Downe S. Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50(2):204–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03380.x.

Garcia-Retamero R, Galesic M. On defensive decision making: how doctors make decisions for their patients. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy. 2014;17(5):664–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00791.x.

Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A Treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care (with CD). Institute of Medicine 2003.

Rathore SS, Lenert LA, Weinfurt KP, Tinoco A, Taleghani CK, Harless W, et al. The effects of patient sex and race on medical students’ ratings of quality of life. Am J Med. 2000;108(7):561–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00352-1.

Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, Kerner JF, Sistrunk S, Gersh BJ, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(8):618–26. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199902253400806.

Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, David-Kasdan JA, Epstein AM. Physicians’ beliefs about racial differences in referral for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2004;43(2):350–7. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.10.022.

Zestcott CA, Blair IV, Stone J. Examining the presence, consequences, and reduction of implicit bias in health care: a narrative review. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2016;19(4):528–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216642029.

Anderson MR, Moscou S, Fulchon C, Neuspiel DR. The role of race in the clinical presentation. Fam Med. 2001;33(6):430–4.

Quiñones AR, O’Neil M, Saha S, et al. Interventions to improve minority health care and reduce racial and ethnic disparities. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2011.

Metzl JM, Roberts DE. Structural competency meets structural racism: race, politics, and the structure of medical knowledge. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16:674. https://doi.org/10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.9.spec1-1409.

McMorrow S, Long SK, Kenney GM, Anderson N. Uninsurance disparities have narrowed for black and Hispanic adults under the affordable care act. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2015;34(10):1774–8. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0757.

Breathett K, D’Amico R, Adesanya TMA, Hatfield S, Willis S, Sturdivant RX, et al. Patient perceptions on facilitating follow-up after heart failure hospitalization. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10(6):e004099. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004099.

Two Feathers J, Kieffer EC, Palmisano G, Anderson M, Sinco B, Janz N, et al. Racial and ethnic approaches to community health (REACH) Detroit partnership: improving diabetes-related outcomes among African American and Latino adults. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1552–60. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.066134.

Thomas KL, Shah BR, Elliot-Bynum S, Thomas KD, Damon K, Allen LaPointe NM, et al. Check it, change it: a community-based, multifaceted intervention to improve blood pressure control. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(6):828–34. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001039.

Verhagen I, Steunenberg B, de Wit NJ, Ros WJ. Community health worker interventions to improve access to health care services for older adults from ethnic minorities: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):497. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0497-1.

Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski JL, Nishikawa B, Morgan LC, Honeycutt AA, Thieda P, et al. Outcomes and costs of community health worker interventions: a systematic review. Med Care. 2010;48(9):792–808. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35b51.

Feagin J, Bennefield Z. Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.006.

Implicit bias review. http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/researchandstrategicinitiatives/implicit-bias-review/. Accessed 27 Nov 2017.

van Ryn M, Burgess DJ, Dovidio JF, Phelan SM, Saha S, Malat J, et al. The impact of racism on clinician cognition, behavior, and clinical decision making. Bois Rev Soc Sci Res Race. 2011;8(01):199–218. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X11000191.

Kawakami K, Phills CE, Steele JR, Dovidio JF. (Close) distance makes the heart grow fonder: improving implicit racial attitudes and interracial interactions through approach behaviors. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(6):957–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.957.

Kubota JT, Banaji MR, Phelps EA. The neuroscience of race. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(7):940–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3136.

Rudman LA, Ashmore RD, Gary ML. “Unlearning” automatic biases: the malleability of implicit prejudice and stereotypes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81(5):856–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.856.

Helping courts address implicit bias: resources for education | National Center for State Courts. http://www.ncsc.org/ibeducation. Accessed 4 Oct 2016.

de Groot E, Endedijk M, Jaarsma D, van Beukelen P, Simons RJ. Development of critically reflective dialogues in communities of health professionals. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2013;18(4):627–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-012-9403-y.

Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Dismantling structural racism, supporting black lives and achieving health equity: our role. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2113–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1609535.

Funding

Dr. Breathett received support from the American Heart Association (AHA) Strategically Focused Research Network (no. 16SFRN29640000), the National Institute of Health (NIH L60 MD010857), the University of Colorado Department of Medicine, Health Services Research Development Grant Award, and the University of Arizona Health Sciences, Strategic Priorities Faculty Initiative Grant. Dr. Jones received support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08HS024569). Dr. Peterson discloses grant funding from the AHA. Otherwise there are no disclosures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Not applicable. This was a retrospective study of previously published publicly available manuscripts.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Breathett, K., Jones, J., Lum, H.D. et al. Factors Related to Physician Clinical Decision-Making for African-American and Hispanic Patients: a Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 5, 1215–1229 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-018-0468-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-018-0468-z