Abstract

Purpose

The Female Muscularity Scale (FMS) was specifically developed for assessing drive for muscularity in women. The current study aimed to translate the FMS into Chinese (FMS-C) and examine its psychometric properties among Chinese young women.

Methods

Based on standard procedures, the FMS was translated into Chinese. By using the psych and lavaan packages on R version 4.0.3, the current study examined the factor structure, reliability, and convergent and incremental validity of the FMS-C with a sample of 517 Chinese women college students (\({M}_{age}\)= 18.86 years).

Results

Results showed a 2-factor structure including attitudes and behaviors of the FMS-C. The internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α) was .91 for the total FMS-C scale and .89 and .88 for the Attitudes and Behaviors subscales, respectively. Results also revealed evidence for good convergent and incremental validity of the FMS-C.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that the FMS-C can be a useful tool to measure both attitudes and behaviors underlying drive for muscularity and muscle tone concerns among Chinese young women.

Level of evidence

Level V, cross-sectional descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although women have long been at the center of body image and eating disorders research, they gain little attention on the topic of muscularity compared to men [1]. Part of this discrepancy may be due to different social standards about bodily attractiveness and ideals among men and women. Women are often encouraged to be much thinner than the average woman’s body shape (e.g., drive for thinness), while the social standard for men is to be more muscular [2,3,4]. The construct of drive for muscularity was originally described as an individual’s desire to achieve an ideal muscular body, which includes both attitudes and behaviors [4]. Although this construct was first developed for exploring male body image concerns, drive for muscularity is becoming an increasing pressure for women [5,6,7,8]. In addition to drive for thinness, being toned has become an important aspect of cultural ideals about the woman’s body [6, 8,9,10,11]. One of the possible reasons for this shift is increased exposure to popular media in which there is a growing percentage of exercise-related content including lean, smooth, and fit models [7, 12]. Indeed, social media tends to present exercise as a viable method of obtaining both thinness and fitness [7].

Interestingly, what men and women desire in terms of muscularity are quite different. Jacobi and colleagues [13] found that 78% of women wanted to be more muscular, but this drive for muscularity also included a desire for thin, toned, and smooth muscles rather than bulky, well-defined muscles [6, 7, 10, 14]. In contrast, the male’s muscular ideal is described as a lean, muscular mesomorphic shape with a well-developed chest and arms [6, 10, 15, 16].

Higher levels of drive for muscularity have been found to be related to negative outcomes [4, 9, 11, 17,18,19]. A systematic review [17] identified that high levels of drive for muscularity were associated with exercise dependence, drug abuse, depression, anxiety, body shame, muscle dysmorphia, dietary manipulation, and impaired social and occupational functioning. Importantly, 79% of the 53 studies selected in this systematic review focused on men, 21% used combined samples of men and women, and none solely focused on women [17]; thus, findings cannot be generalized to women. However, due to the increasing research interest on sex roles in drive for muscularity and its association with negative outcomes, some recent studies show that drive for muscularity was also related to body image concerns and disordered eating among women [6, 9, 20].

Of note, drive for muscularity is a relatively newer concept in the body image literature and its presence and assessment in women is vastly underexplored relative to men. The most commonly used measurement of drive for muscularity is the Drive for Muscularity Scale (DMS) which showed a 2-factor structure (muscularity attitudes and behaviors) in men [2, 4] and has been used in both men and women [2, 9]. However, some of the items on the DMS appear to be inappropriate for women (e.g., “I think I would look better if I gained 10 pounds in bulk.”) [2, 9]. To this end, the assessment of drive for muscularity via the DMS may not be suitable for women due to some discrepancies in core elements of drive for muscularity between men and women. To help address these discrepancies, the Female Muscularity Scale (FMS) was developed to specifically assess muscularity concerns among women [6].

The FMS has been reported to have a 2-factor structure (attitudes and behaviors), both in the original [6] and Brazilian [20] versions. The FMS has also shown good test–retest reliability and good divergent and convergent validity [6, 20]. For example, Rodgers and colleagues [6] reported moderate-to-large associations between the FMS overall and body image concerns (r = 0.42, p < 0.01), and also the attitudes subscale and body image concerns (r = 0.44, p < 0.01). Campos and colleagues [20] found that the FMS was associated with higher drive for muscularity (r = 0.54, p < 0.01), higher disordered eating (r = 0.45, p < 0.01), and lower overall body satisfaction (r = − 0.23, p < 0.01). Taken together, muscularity-related concerns in women have been documented in mainly English-speaking and Western countries [5, 6], but limited research has examined drive for muscularity and associated correlates via the FMS in non-Western countries like China.

With the widespread use of social media and the influence of Western culture, bodybuilding and fitness are becoming popular trends in China [21, 22]. For example, bodybuilding-related videos for women increased rapidly in Chinese popular media (e.g., Blibli [23]). Mirroring the shift of cultural ideals of the female body from thinness to both thinness and being toned in Western countries [6], Chinese women have also started to internalize fitness and thinness rather than pure thinness as body image ideals [23]. However, there is paucity of research exploring drive for muscularity in Chinese women which may be due to the fact that there are no valid measures available in China for assessing women’s muscularity-oriented body image disturbances.

The current study

To bridge the research gap discussed above, the current study aimed to translate the Female Muscularity Scale (FMS) into Chinese (i.e., FMS-C) and examine its psychometric properties among Chinese young women. According to previous findings, the current study hypothesized that: (1) the FMS-C would present a 2-factor structure; (2) the FMS-C would have adequate internal consistency reliability; (3) the FMS-C would be closely related with drive for muscularity scale (DMS) but the FMS-C would be more suitable for women; (4) based on sociocultural theories of body image (e.g., the tripartite influence model [24]) and the objectification theory [25], as well as existing empirical findings on drive for muscularity in women [6, 9, 20], the scores of the FMS-C were hypothesized to demonstrate convergent validity via positive relationships with negative psychological measures (e.g., psychosocial impairment, thinness-oriented body image dissatisfaction, body image inflexibility, thinness-oriented eating disorder symptomatology); and (5) the FMS-C would demonstrate incremental validity via FMS-C scores explaining significant variance in thinness-oriented eating disorder symptomatology after controlling for thinness-oriented body image dissatisfaction and covariates (e.g., age, BMI).

Method

Participants and procedure

The data used in the current study were from a project about Chinese cross-cultural adaption of eating and body image measures. The protocol of the project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen (No. EF20201024001). The project contained two different datasets collected from undergraduate students at two different universities (i.e., Hunan Agriculture University and Hunan University of Chinese Medicine) from Hunan Province, China. The dataset used in the current study was from the Hunan University of Chinese Medicine. The survey was conducted in a paper-and-pencil format. Psychological teachers at the two universities introduced the project (e.g., the goals of the study) to the first- and second-year undergraduate students during class time and invited them to participate. Finally, 812 undergraduate students (63.7% women; 517) were included and all participants provided informed consent. Afterward, to ensure quality data entry, survey data were inputted by well-trained research assistants via EpiData (https://www.epidata.dk/) which, as a professional data entry software, has built-in error detection features. More details about the sampling procedure can be found in our previous publication using the male sample [26]. As the current study is about women’s body image, only the sample of 517 women was used in the current study, and they had a mean age of 18.86 (SD = 0.96) years. Body mass index (BMI) was obtained with self-reported height and weight which was calculated by the division of weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. The sample had a mean BMI of 20.49 (SD = 2.95) kg/m2.

Scale translation

In obtaining the FMS-C, the English version of the FMS was first translated to Chinese (Mandarin) based on the guidelines from Beaton and colleagues (2000) as recommended by Swami and colleagues [27]. Specifically, two bilingual postgraduate students (Chinese and English) first translated the scale into Chinese independently. After the first translation, the two translations were compared and differences discussed, resulting in a synthesized translation. Back-translation was conducted independently by a new postgraduate student and an undergraduate student. Both the postgraduate and undergraduate students were bilingual (Chinese and English) and they had no prior knowledge about the FMS. Afterward, the research team, consisting of two experts in body image and the four translators, evaluated the forward- and back-translations (in this process, the developer of the FMS, Rachel Rodgers, also helped review the back-translations and gave comments). After some minor revisions on the wording of certain items, a pre-final Chinese translation of the FMS was obtained. During the next piloting, we recruited 30 Chinese women university students to test the meanings, clarity, and understandability of the items in the pre-final Chinese translation. However, 4 did not attend the focus-group interviews because the schedule of the interviews overlapped with their classes. These 26 students were asked to rate each item from 1 (“I don’t understand this item at all/this item is very unclear.") to 5 (“I totally understand this item very much/this item is very clear.”). Based on the responses and feedback of the 26 students in the focus-group interviews, all students were able to correctly interpret each item of the scale with a mean of 4.65. As such, the preliminary Chinese translation (FMS-C) was approved by the research team without any further revisions.

Measures

Female muscularity scale (FMS)

The Female Muscularity Scale (FMS) [6] was used to measure drive for muscularity in women which has received support as a promising measure of muscularity concerns in young adult women [6, 20]. The FMS includes 10 items, scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale, with response options from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Higher total scores indicated greater levels of drive for muscularity. Previous studies have confirmed that the FMS has a 2-factor structure, both in U.S. [6] and Brazilian [20] versions, including a five-item Attitudes subscale and a five-item Behaviors subscale. Example items include “I wish my body was tighter.” (attitudes) and “I exercise to try and look fit and sculpted.” (behaviors). In this study, the aforementioned Chinese translated version was used.

Drive for muscularity scale (DMS)

The 15-item Drive for Muscularity Scale (DMS) [2, 4] was used in this study to measure drive for muscularity. Previous low-order exploratory factor analysis has confirmed 2 factors (muscularity attitudes and behaviors) for men while higher-order EFA, using the male 2-factor structure, revealed the presence of a single, higher-order DMS factor of use across both sexes [2, 4]. Example items are “I think my legs are not muscular enough.” and “I lift weights to build up muscle.” Each item is scored on a 6-point Likert-type scale, with response options from 1 (always) to 6 (never). Higher total scores indicated higher levels of drive for muscularity. The Chinese version of DMS was obtained in similar procedures as the FMS-C and showed good internal consistency reliability and incremental validity in Chinese adult men [26]. In this study, the Chinese version of the DMS (total score) had a Cronbach’s α of 0.84.

Body image acceptance and action questionnaire (BI-AAQ)

The Body Image-Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (BI-AAQ) [28] was used to measure body image inflexibility. In the original questionnaire, BI-AAQ has 12 items. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 7 (always true), with higher scores indicating higher levels of body image inflexibility. An example item is “Worrying about my weight makes it difficult for me to live a life that I value.” The short form of the BI-AAQ (BI-AAQ-5) was confirmed to have comparable performance to the long-form (BI-AAQ) in terms of its factor structure and correlations with theoretically related constructs [29]. In this study, the Chinese version of the 5-item Body Image-Acceptance and Action Questionnaire [30] was used. The Chinese BI-AAQ-5 has exhibited good internal consistency reliability and convergent validity [30]. In this study, the Chinese version of the BI-AAQ-5 had a Cronbach’s α of 0.92.

Eating disorder inventory—body dissatisfaction subscale (EDI-BD)

To measure thinness-oriented body dissatisfaction, the Body Dissatisfaction subscale of the Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI-BD) [31] was administered. The EDI-BD subscale has 9 items. An example item is “I think that my thighs are too large.” Each item has response options ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always). Five items are reverse scored. Higher total scores indicated higher levels of body dissatisfaction. In this study, the Chinese version of the EDI [32, 33] was used, and it has demonstrated good internal consistency reliability and good convergent and discriminant validity in both clinical and non-clinical Chinese populations [32, 33]. In this study, the Chinese version of the EDI-BD had a Cronbach’s \(\alpha\) of 0.92.

Clinical impairment assessment questionnaire (CIA)

The 16-item Clinical Impairment Assessment (CIA 3.0) [34] was used to measure severity of psychosocial impairment as a result of eating disorder symptoms. An example item is “Over the past 28 days, to what extent have your eating habits … shape or weight made it difficult to concentrate?” Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (always). All items are summed to get a total score, and higher scores indicated higher levels of psychosocial impairment. The Chinese version of the CIA 3.0 [26, 35] was used in the current study, and it showed good internal consistency and test–retest reliability, as well as good construct validity in the Chinese context [35]. In the current study, the Chinese version of the CIA 3.0 had a Cronbach’s α of 0.93.

Short form of the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-QS)

The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire-Short form (EDE-QS) [36] was used to measure thinness-oriented eating disorder symptomatology. EDE-QS contains 12 items, with response options ranging from 0 to 3. Scores of items are summed, and higher scores indicated higher levels of eating disorder symptomatology. An example item is “Have you had a sense of having lost control over your eating (at the time that you were eating)?” The Chinese version of the EDE-QS [37] was used in this study. The EDE-QS showed good internal consistency reliability, test–retest reliability, and convergent validity in the Chinese context [37]. In the current study, the Chinese version of the EDE-QS had a Cronbach’s \(\alpha\) of 0.86.

Statistical analysis

The psych package version 2.1.6 [38] and the lavaan package version 0.6–8 [39] on R version 4.0.3 [40] were used for data analyses. The total sample (N = 517) was randomly split into two nearly equal subsamples. Based on the results of independent t tests, the two samples were similar in all key variables (e.g., EDE-QS scores). Thus, one subsample (n = 258) was used for conducting exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and the other (n = 259) was used for conducting confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

EFA has been confirmed as an appropriate method for ordinal data derived from Likert-type scales [41]. In the current study, Oblimin rotation and the ordinary least squares estimator was used [42]. The parallel analysis was also used to determine the number of factors [43]. As recommended by Hair [44], factor loadings greater than 0.4 are considered adequate.

For CFA, the current study used the mean- and variance-adjusted weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV) for model estimation because WLSMV was confirmed to be less biased and more accurate than MLR in estimating the factor loadings for Likert-type rating scales [45]. In this study, the items of the FMS-C were rated on a Likert scale which produced ordinal responses. To evaluate model fit, several model fit indices were used such as comparative fit index (CFI), tucker-lewis index (TLI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) [30]. The following commonly adopted cut-offs have been outlined in previous research [46]: both CFI and TLI greater or equal to 0.95 indicate a good fit, while greater or equal to 0.90 indicate an acceptable fit, and SRMR less than or equal to 0.06 indicates a good fit while SRMR less than or equal to 0.08 indicates an acceptable fit. This study did not report the RMSEA as it was unreliable when used in ordinal responses by consistently rejecting closely-fitted models when sample sizes were large and data contained 5 categories [47].

Internal consistency reliability of the FMS-C was assessed by ordinal Cronbach’s α (a value greater than 0.70 is acceptable) [48]. In addition, the current study evaluated the convergent validity of the FMS-C by exploring the bivariate correlations between scores on the FMS-C and theoretically-related constructs. Since previous research on the DMS revealed the presence of a single, higher-order factor in both sexes [2], the current study assumed that the FMS-C would have a moderate positive correlation with the DMS. According to previous research [6, 9, 20], the current study expected significant and positive associations between FMS-C scores and negative psychological constructs (e.g., body dissatisfaction, eating disorder symptoms). To examine incremental validity, hierarchical multiple regressions examined whether drive for muscularity as measured by the FMS-C could explain significant variance in eating disorder symptoms, as measured by the EDE-QS, above and beyond confounding variables such as age, BMI, and body dissatisfaction.

For interpreting effect sizes, the current study relied on the recommendations from Cohen [49], with correlations of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 equating small, medium, and large effects, respectively.

Results

Preliminary analyses

The rate of missing data for the FMS-C items ranged from 0.2–0.4%. Little’s Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) test showed \({\chi }^{2}\)(18) = 10.75 (p = 0.905), indicating that these missing data were MCAR. We decided not to impute these missing data in subsequent analyses due to the low missing rate (i.e., less than 5%), as well as the missing pattern of MCAR [50].

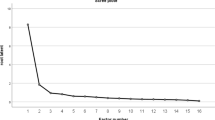

Exploratory factor analysis

Parallel analysis scree plot (Fig. 1) supported our assumption of a 2-factor structure of the FMS-C, with the two factors from the actual data having greater eigen values than the criterion eigen values generated from the random data (λ1 = 4.73 > 0.64, λ2 = 1.04 > 0.23, and λ3 = 0.13 < 0.17). The first factor (i.e., behaviors) and the second factor (i.e., attitudes) accounted for 37% and 34% of the total variance, respectively. The detailed information of the item loadings is shown in Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis

Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, and standardized factor loadings for the items of the FMS-C. Specifically, the standardized factor loadings of the items ranged from 0.80 to 0.96. Based on the recommended model fit cut-offs from Hu and colleagues [46], fit indices, \({\chi }^{2}\) = 188.86 (df = 34, p < 0.001), CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.07, provided sufficient support for a 2-factor structure of the FMS-C. In addition, to test whether the FMS-C can be used to describe a total score (or whether there is an overarching factor), we further examined a bi-factor model of the FMS-C. Results showed that the bi-factor model fitted the data well, with \({\chi }^{2}\) = 94.55 (df = 26, p < 0.001), CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.04.

Reliability

Regarding the reliability of the FMS-C, the results showed that the ordinal Cronbach’s α for the total FMS-C score was 0.91, suggesting good internal consistency reliability of the scale. Furthermore, the ordinal Cronbach’s α of the two subscales (attitudes and behaviors subscales) also suggested good internal consistency reliability, 0.89 and 0.88, respectively.

Convergent validity

Bivariate correlations revealed good convergent validity of the FMS-C. As shown in Table 3, drive for muscularity as represented by the total score of the FMS-C was significantly and positively correlated with drive for muscularity (DMS) (medium to large effect sizes), and significantly and positively correlated with thinness-oriented body dissatisfaction (small to medium effect sizes), thinness-oriented eating disorder symptomatology (medium to large effect sizes), body image inflexibility (medium effect sizes), and psychosocial impairment (small to medium effect sizes).

Furthermore, bivariate correlations between the subscales of the FMS-C and body dissatisfaction, drive for muscularity (i.e., DMS), eating disorder symptomatology, body image inflexibility, and psychosocial impairment also revealed similar results as those observed for the total score of the FMS-C (see Table 3).

Incremental validity

Table 4 presents the hierarchical regression model with the FMS-C total score entered in step 2. Specifically, results showed that inclusion of the FMS-C significantly increased the variance explained in thinness-oriented eating disorder symptomology (\(\Delta\)R2 = 0.03, p < 0.001), above and beyond potential confounds of age, BMI, and thinness-oriented body dissatisfaction.

Discussion

The current study aimed to translate the Female Muscularity Scale into Chinese (Mandarin; FMS-C) and to examine the psychometric properties of the FMS-C. In line with our hypotheses, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) indicated a 2-factor structure of the FMS-C, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) reported good model fit of the two-factor structure (attitudes and behaviors) for the FMS-C. Moreover, the support for a bi-factor model of the FMS-C also suggests that the use of the total score of the FMS represents drive for muscularity in women. These findings were also compatible with previous studies [6, 20]; thus, the factor structure of the FMS remains stable across three countries (i.e., U.S., Brazil, and China). As in He and colleagues [51], future research examining the cross-cultural measurement invariance of the FMS is needed to test for potential cultural differences in drive for muscularity among women. Such research is an important first step in building on our understanding of cultural differences in drive for muscularity among women.

Similar to Campos and colleagues [20], the FMS-C scores were found to be significantly and positively associated with the DMS. Furthermore, the associations between the FMS-C and convergent measures were stronger than associations between convergent measures and the DMS. This may be because the ideal body image of women, as measured by the FMS, emphasizes thinness and body tone, while the ideal body image of men, as measured by the DMS, emphasizes bulky muscles [10, 15]. Furthermore, the DMS, as opposed to the FMS, is more focused on male-specific muscularity desires and practices. Together, such findings indicated that the FMS-C was more suitable for measuring drive for muscularity in women than the DMS.

In addition, the current study found a significant and positive relationship between drive for muscularity and thinness-oriented eating disorder symptomatology. In media, bodybuilding or exercise is often promoted as a good approach to obtaining both thinness and fitness [7]. In this case, the outcome of drive for muscularity in women partly overlapped with this drive for thinness. Building on these findings, research in the Chinese context also supports the positive relationship between thinness-oriented body dissatisfaction and disordered eating [52,53,54].

Furthermore, the FMS-C contributed a significant amount of variance in thinness-oriented eating disorder symptomatology, above and beyond relevant confounds of age, BMI, and thinness-oriented body dissatisfaction, indicating good incremental validity of the FMS-C. Taken together, the current study provides evidence for the FMS-C to be a useful instrument for assessing drive of muscularity and its potential correlates (e.g., thinness-oriented eating disorder symptomatology) in Chinese young women.

Limitation and future directions

The current study is not without limitations, and several future research directions exist. First, the sample used in this study was homogeneous, consisting of women college students. Future studies should use more representative samples and/or examine different age groups to widen the potential utility of the FMS-C to probe drive for muscularity in diverse groups of Chinese women. Second, we did not assess the test–retest reliability of the FMS-C which is an essential property of the measure indicating stability of the construct over time; thus, test–retest reliability of the FMS-C should be examined in future research. Third, this study did not measure exercise engagement, which has been done in previous studies [4, 6]. Exercise engagement or exercise amount is a good indicator of behaviors assessed with drive for muscularity scales (e.g., FMS-C). To this end, exercise engagement can be used to corroborate participants’ self-reported data in the behavior subscale. Future research should adopt a more comprehensive assessment of health behaviors including physical activity to more precisely define the role of drive for muscularity on health outcomes, including eating and body image, in women.

Conclusion

The current study aimed to translate the FMS into Chinese (Mandarin; FMS-C) and examine its psychometric properties among Chinese young women. The FMS-C revealed a two-factor structure and was confirmed to have good internal consistency reliability and convergent and incremental validity. Altogether, the FMS-C may be a useful tool to measure attitudinal and behavioral components of muscularity and muscle tone concerns among Chinese young women.

What is already known on this subject?

Ample evidence shows that drive for muscularity is associated with disordered eating and body image concerns for both men and women. Even though the DMS has been developed for assessing drive for muscularity, the DMS was based on conceptualizations of men’s, not women’s, ideal body image. Considering sex differences in drive for muscularity, the FMS was developed for assessing drive for muscularity in women. Currently, there is no such instrument available in Chinese for measuring women’s drive for muscularity.

What this study adds?

The FMS was translated into Chinese based on standard procedures (FMS-C). The FMS-C showed good psychometric properties in Chinese young women, including a 2-factor structure, good internal consistency reliability, and good convergent and incremental validity. The FMS-C may be a useful tool to measure drive for muscularity in Chinese young women.

Availability of data and material

The dataset used during the current study is available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Grogan S, Evans R, Wright S, Hunter G (2004) Femininity and muscularity: accounts of seven women body builders. J Gend Stud 13(1):49–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/0958923032000184970

McCreary DR, Sasse DK, Saucier DM, Dorsch KD (2004) Measuring the drive for muscularity: factorial validity of the drive for muscularity scale in men and women. Psychol Men Masc 5(1):49–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.5.1.49

McCreary DR, Sadava SW (2001) Gender differences in relationships among perceived attractiveness, life satisfaction, and health in adults as a function of body mass index and perceived weight. Psychol Men Masc 2(2):108–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.2.2.108

McCreary DR, Sasse DK (2000) An exploration of the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. J Am Coll Health 48(6):297–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480009596271

Thompson JK, Cafri G (2007) The muscular ideal: psychological, social, and medical perspectives. American Psychological Association, Washington

Rodgers RF, Franko DL, Lovering ME, Luk S, Pernal W, Matsumoto A (2018) Development and validation of the female muscularity scale. Sex Roles 78(1–2):18–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0775-6

Homan K (2010) Athletic-ideal and thin-ideal internalization as prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction, dieting, and compulsive exercise. Body Image 7(3):240–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.02.004

Homan K, McHugh E, Wells D, Watson C, King C (2012) The effect of viewing ultra-fit images on college women’s body dissatisfaction. Body Image 9(1):50–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.07.006

de Carvalho PHB, Oliveira FDC, Neves CM, Meireles JFF, Ferreira MEC (2019) Is the drive for muscularity scale a valid and reliable instrument for young adult women? Body Image 29:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.02.001

Cramblitt B, Pritchard M (2013) Media’s influence on the drive for muscularity in undergraduates. Eat Behav 14(4):441–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.08.003

McCreary DR, Saucier DM (2009) Drive for muscularity, body comparison, and social physique anxiety in men and women. Body Image 6(1):24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.09.002

Wiseman CV, Gray JJ, Mosimann JE, Ahrens AH (1992) Cultural expectations of thinness in women - an update. Int J Eat Disord 11(1):85–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108x(199201)11:1%3c85::Aid-Eat2260110112%3e3.0.Co;2-T

Jacobi L, Cash TF (1994) In pursuit of the perfect appearance: discrepancies among self-ideal percepts of multiple physical attributes 1. J Appl Soc Psychol 24(5):379–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1994.tb00588.x

Kyrejto JW, Mosewich AD, Kowalski KC, Mack DE, Crocker PRE (2008) Men’s and women’s drive for muscularity: gender differences and cognitive and behavioral correlates. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol 6(1):69–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2008.9671855

Hargreaves DA, Tiggemann M (2004) Idealized media images and adolescent body image: “comparing” boys and girls. Body Image 1(4):351–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.10.002

Leit RA, Pope HG Jr, Gray JJ (2001) Cultural expectations of muscularity in men: the evolution of playgirl centerfolds. Int J Eat Disord 29(1):90–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108x(200101)29:1%3c90::aid-eat15%3e3.0.co;2-f

Edwards C, Tod D, Molnar G (2014) A systematic review of the drive for muscularity research area. Int Rev Sport Exer Psychol 7(1):18–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984x.2013.847113

Maida D, Armstrong S (2005) The classification of muscle dysmorphia. Int J Mens Health 4(1):73–91. https://doi.org/10.3149/jmh.0401.73

Pope HG, Gruber AJ, Choi P, Olivardia R, Phillips KA (1997) Muscle dysmorphia: an underrecognized form of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics 38(6):548–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0033-3182(97)71400-2

Campos PF, Almeida M, Neves CM, Rodgers RF, Ferreira MEC, de Carvalho PHB (2021) Assessing the rising emphasis on muscularity for women: psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the female muscularity scale. Sex Roles. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01222-1

Zhao B (2017) Shenti wenhua shijiao xia jianmei yundong de meixue chanshi [An aesthetic interpretation of bodybuilding from the perspective of body culture]. Tiyu xuekan 24(3):30–34. https://doi.org/10.16237/j.cnki.cn44-1404/g8.20170412.008

Chen BP, Wang ZX (2018) Jianshen jianmei yundong zai gaoxiao xingqi de yuanyin fenxi [Analysis of the reasons for the rise of fitness and bodybuilding sports in colleges and universities]. Zhiku shidai 46:286–294

Liu C, Li B (2021) Xinmeiti jingguan xia nvxing jianshen linian de shanbian yu chongsu [The transmutation and reshaping of women’s fitness concepts in the new media landscape]. Xinwen yanjiu daokan 13:101–103

Van den Berg P, Thompson JK, Obremski-Brandon K, Coovert M (2002) The tripartite influence model of body image and eating disturbance: a covariance structure modeling investigation testing the mediational role of appearance comparison. J Psychosom Res 53(5):1007–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00499-3

Fredrickson BL, Roberts TA (1997) Objectification theory: toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychol Women Q 21(2):173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

He J, Murray S, Compte EJ, Song J, Nagata JM (2021) The muscularity-oriented eating test, drive for muscularity scale, and muscle dysmorphic disorder inventory among chinese men: confirmatory factor analyses. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(21):11690. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111690

Swami V, Barron D (2019) Translation and validation of body image instruments: Challenges, good practice guidelines, and reporting recommendations for test adaptation. Body Image 31:204–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.08.014

Sandoz EK, Wilson KG, Merwin RM, Kellum KK (2013) Assessment of body image flexibility: the body image-acceptance and action questionnaire. J Contextual Behav Sci 2(1–2):39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2013.03.002

Basarkod G, Sahdra B, Ciarrochi J (2018) Body image-acceptance and action questionnaire-5: an abbreviation using genetic algorithms. Behav Ther 49(3):388–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.09.006

He J, Cai Z, Chen X, Lu T, Fan X (2021) Validation of the Chinese version of the body image acceptance and action questionnaire and the mediating role of body image flexibility in the relationship between body dissatisfaction and psychological distress. Behav Ther 52(3):539–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2020.07.003

Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Polivy J (1983) Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia-nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eat Disord 2(2):15–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108x(198321)2:2%3c15::Aid-Eat2260020203%3e3.0.Co;2-6

Tseng MC, Yao G, Hu FC, Chen KY, Fang D (2014) Psychometric properties of the eating disorder inventory in clinical and nonclinical populations in Taiwan. Assessment 21(1):50–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111428761

Tseng M, Ko H, Lee M (2001) Reliability and validity of the Mandarin Chinese version of the eating disorder inventory (full text in Chinese with English abstract). Formos J Med 5:379–388

Bohn K, Doll HA, Cooper Z, O’Connor M, Palmer RL, Fairburn CG (2008) The measurement of impairment due to eating disorder psychopathology. Behav Res Ther 46(10):1105–1110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.012

He J, Brytek-Matera A, Cooper M, Cui S, Chen G (2022) Chinese translation of the Clinical Impairment Assessment (CIA 3.0): Psychometric properties and measurement invariance across sex and age in adolescents, young adults, and adult men. Eat Behav 45:101623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2022.101623

Gideon N, Hawkes N, Mond J, Saunders R, Tchanturia K, Serpell L (2016) Development and psychometric validation of the EDE-QS, a 12 item short form of the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q). PLoS ONE 11(5):e0152744. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152744

He J, Sun S, Fan X (2021) Validation of the 12-item short form of the eating disorder examination questionnaire in the Chinese context: confirmatory factor analysis and rasch analysis. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorex Bulim Obes 26(1):201–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00840-3

Revelle WR (2017) Psych: procedures for personality and psychological research. Northwestern University. https://personality-project.org/r/psych/

Rosseel Y (2012) Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5–12 (BETA). J Stat Softw 48(2):1–36

Team RC (2020) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

Baglin J (2014) Improving your exploratory factor analysis for ordinal data: a demonstration using FACTOR. Pract Assess Res Eval 19(1):5. https://doi.org/10.7275/dsep-4220

Lee CT, Zhang G, Edwards MC (2012) Ordinary least squares estimation of parameters in exploratory factor analysis with ordinal data. Multivar Behav Res 47(2):314–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2012.658340

Çokluk Ö, Koçak D (2016) Using Horn’s parallel analysis method in exploratory factor analysis for determining the number of factors. Educ Sci Theory Pract 16(2):537–551. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2016.2.0328

Hair JF (2009) Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective, 7th edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

Li CH (2016) Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav Res Methods 48(3):936–949. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Shi D, Maydeu-Olivares A, Rosseel Y (2019) Assessing fit in ordinal factor analysis models: SRMR vs RMSEA. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J 27(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2019.1611434

Gadermann AM, Guhn M, Zumbo BD (2012) Estimating ordinal reliability for Likert-type and ordinal item response data: a conceptual, empirical, and practical guide. Pract Assess Res Eval 17(1):3. https://doi.org/10.7275/n560-j767

Cohen J (1992) A power primer. Psychol Bull 112(1):155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155

Schafer JL (1999) Multiple imputation: a primer. Stat Methods Med Res 8(1):3–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/096228029900800102

He J, Zickgraf HF, Ellis JM, Lin Z, Fan X (2021) Chinese version of the nine item ARFID screen: psychometric properties and cross-cultural measurement invariance. Assessment 28(2):537–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191120936359

Chen G, He J, Zhang B, Fan X (2021) Revisiting the relationship between body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms in Chinese adolescents: the mediating roles of regulatory emotional self-efficacy and depression symptoms. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorex Bulim Obes 26(1):239–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00848-0

Tang C, Cooper M, Wang S, Song J, He J (2021) The relationship between body weight and dietary restraint is explained by body dissatisfaction and body image inflexibility among young adults in China. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorex Bulim Obes 26(6):1863–1870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01032-0

Chen X, Luo Y-j, Chen H (2020) Body image victimization experiences and disordered eating behaviors among Chinese female adolescents: the role of body dissatisfaction and depression. Sex Roles 83(7):442–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01122-4

Funding

The study was supported by the Presidential Fund of The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, to Jinbo He (Grant Number: PF.01.001428).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CT: analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. WRB: reviewed and revised the manuscript. BZ: collected data and reviewed and revised the manuscript. JH: designed the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the research committee of The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the surveyed participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, C., Barnhart, W.R., Zhang, B. et al. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Female Muscularity Scale among Chinese young women. Eat Weight Disord 27, 3187–3196 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01448-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01448-w