Abstract

Purpose

Maladaptive exercise is common among individuals with binge-spectrum eating disorders. One mechanism that may drive engagement in exercise in this population is state body dissatisfaction. However, no studies to date have examined prospective, momentary relationships between state body dissatisfaction and exercise.

Methods

Adults with binge-spectrum eating disorders (N = 58) completed a 7–14-day ecological momentary assessment protocol assessing exercise and state body dissatisfaction several times per day. Multilevel models were used to evaluate prospective reciprocal associations between state body dissatisfaction and exercise. Mixed models examined trajectories of change in state body dissatisfaction pre- and post-exercise. Additional models examined exercise type (maladaptive vs. adaptive) as a moderator.

Results

Momentary increases (i.e., greater than one’s average levels) in state body dissatisfaction at any given timepoint did not prospectively predict engagement in exercise at the next nearest timepoint. Exercise at any given timepoint did not prospectively predict momentary increases in state body dissatisfaction. State body dissatisfaction was found to increase in the initial hours preceding an exercise episode (linear estimate, β = − 0.012, p = 0.004). State body dissatisfaction did not significantly change in the hours following engagement in exercise. Exercise type did not moderate these associations.

Conclusion

If replicated, our results may suggest that momentary increases in state body dissatisfaction may not be associated with exercise behaviors in individuals with binge-spectrum eating disorders.

Level of evidence

Level V: Opinions of authorities, based on descriptive studies, narrative reviews, clinical experience, orreports of expert committees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Exercise is common among individuals with binge-spectrum eating disorders (e.g., Bulimia Nervosa and Binge Eating Disorder) [1]. Generally, exercise engagement in binge-spectrum eating disorders can perpetuate eating pathology. Increased engagement in exercise increases binge eating and/or maintenance of low weight which, in turn, reinforces overvaluation of shape/weight and eating pathology. Increased engagement in exercise is associated with deleterious negative consequences [2] as well as poor treatment outcomes (e.g., lower remission rates and higher relapse) [3].

Exercise engagement in binge-spectrum eating disorders is complex. While up to 51% of individuals with binge-spectrum eating disorders have shown to engage in maladaptive exercise (described as exercise that is ‘compensatory’, i.e., designed to “compensate for” calories consumed, and/or ‘driven’, i.e., feeling compelled to exercise due to fears of weight gain in nature) [4,5,6,7,8], there is some evidence that a subset of individuals engage in adaptive exercise [5]. Studies have shown that some individuals with binge-spectrum eating disorders engage in exercise that is adaptive in nature (e.g., for social connection, prioritizing health, and improving mood) [5, 9]. In addition, research have demonstrated that there is considerable variability in the type of exercise (maladaptive vs. adaptive) among individual having binge eating pathology [9]. For example, even among individuals who engage in maladaptive exercise, not all exercise episodes are necessarily maladaptive; individuals may engage in some exercise to promote positive affect [10], or for other perceived social or health benefits [11] without it feeling driven/compelled or being undertaken to compensate for eating. Given that maladaptive exercise can be considerably problematic but adaptive exercise can be considerably beneficial, it is imperative to understand what factors maintain both maladaptive and adaptive exercise. Understanding such maintenance factors may help to design targeted treatments to address maladaptive exercise without discouraging adaptive exercise.

One possible maintaining factor of engagement in both adaptive and maladaptive exercise may be state body dissatisfaction (i.e., transitory negative attitude towards one’s appearance in a given context). Momentary increases in state body dissatisfaction (i.e., greater than one’s average levels of state body dissatisfaction) may reduce following an exercise episode, and thus, state body dissatisfaction may maintain exercise engagement [4, 12]. One study utilizing ecological momentary assessment (EMA) approach in a college sample with high trait body dissatisfaction found that when individuals were asked to rate body dissatisfaction following an exercise episode, they reported lowered state body dissatisfaction compared to when they rated state body dissatisfaction in the absence of exercise engagement [13]. Similarly, another study found that in-lab exercise had a positive effect on state body dissatisfaction immediately following the exercise engagement, especially in participants with higher overall body image disturbances [14]. As these studies assessed state body dissatisfaction after exercise engagement, it remains unknown whether momentary elevations state body dissatisfaction precede and precipitate exercise engagement. In addition, these studies assessed relationship between exercise and state body dissatisfaction in a non-clinical sample, which precludes from understanding the association between exercise and state body dissatisfaction in individuals with binge-spectrum eating disorders. Finally, studies have yet to examine the reciprocal association between exercise and state body dissatisfaction. Understanding reciprocal associations between exercise behaviors and state body dissatisfaction at a momentary level, within a clinical sample and in a naturalistic setting will help to clarify the role of state body dissatisfaction in maintaining exercise engagement and inform treatments for exercise in binge-spectrum eating disorders, and thus, research is warranted.

To further clarify the role of state body dissatisfaction in maintaining exercise engagement, it may be worth examining the trajectory of change in state body dissatisfaction in the hours preceding and following an exercise episode, which could also have important treatment implications. For example, it may be possible that patients reliably experience steady increase in their state body dissatisfaction in hours preceding exercise engagement, and a steep decline in state body dissatisfaction in hours following an exercise episode. Clinicians could use this information to educate patients about when they are at risk for exercise engagement and how to manage momentary increases in state body dissatisfaction. In addition, because maladaptive exercise is designed to influence shape and weight, individuals with binge-spectrum eating disorders who overvalue shape and weight may be more at risk for exercise engagement and experience steeper increases in state body dissatisfaction prior to and following an exercise episode [15, 16]. Thus, clinicians may educate the patients that steep decline in state body dissatisfaction reinforces engagement in exercise and eating pathology. The clinical implications of elucidating the temporal relationship between exercise and state body dissatisfaction suggest a need for further research.

When considering state body dissatisfaction as a maintenance factor for exercise, one must consider that the type of exercise (i.e., maladaptive vs. adaptive exercise) may influence the association between state body dissatisfaction and exercise engagement. Understanding the influence of the maladaptive versus adaptive nature of exercise on associations between state body dissatisfaction and exercise engagement, and on the trajectory of change in state body dissatisfaction in the hours preceding and following exercise may be important to inform treatments for reducing maladaptive exercise and promoting adaptive exercise.

The current study aims to (1) examine whether momentary increases in state body dissatisfaction at any given timepoint (i.e., time1) predict engagement in exercise in the following timepoint (i.e., time2) and whether the type of exercise (maladaptive vs. adaptive) moderates this association and (2) assess whether exercise engagement at time1 predicts decreases in state body dissatisfaction at time2 and whether exercise type moderates this association. As this study aims to clarify the role of state body dissatisfaction in maintaining exercise engagement by examining whether momentary elevations in state body dissatisfaction prospectively predicts exercise engagement and does exercise engagement prospectively improve state body dissatisfaction, the present study focused on investigating the within-subject relationship between these two variables. An exploratory aim of the current study is to examine trajectories of state body dissatisfaction pre- and post-exercise and investigate whether exercise type moderates these trajectories.

Methods

Participants

We recruited adults with clinically significant binge-spectrum eating disorders from the community (N = 58). Of the 147 individuals screened for participation, 75 were excluded and 17 declined to participate. Individuals with binge-spectrum eating disorders were included in the current study because this population has shown to engage in low levels of maladaptive exercise [5]. Participants were included in the study if they: (1) were 18 years of age or older, (2) experienced an average of at least one objective or subjective binge eating episode per week over the previous 12 weeks, (3) had a smartphone and were willing to complete surveys on it for the course of the study, (4) were enrolled to participate in a treatment-based study in the Center for Weight, Eating, and Lifestyle Science (WELL Center) and had at least 7 days before their first treatment session, and (5) were located in the US and are willing and able to participate in remote interventions and assessments. Participants were excluded from the study if they: (1) were unable to fluently speak, write, and read English, (2) were below a BMI of 18.5, (3) were planning to begin, or were currently participating in, another weight loss treatment or psychotherapy for binge eating and/or weight loss in the next 16 months, or (4) had a mental handicap or were currently experiencing other severe psychopathology that would limit their ability to engage in the treatment program (e.g., severe depression, substance dependence, and active psychotic disorder).

Procedures

Recruitment. Participants were recruited from the community using radio and social media advertising for eating disorder treatment. Once eligibility was determined for treatment, participants were offered the opportunity to participate in an EMA study between their baseline assessment and first treatment session. Participants then provided informed consent for their participation and were contacted by study personnel to set up the EMA application on their smartphone. Participants also received training on several relevant constructs to the EMA surveys such as definitions of maladaptive and adaptive exercise. Driven exercise was described as exercise that is characterized by feeling compelled to exercise, regardless of other factors. For example, this includes exercising even though one may be sick, injured, or have other obligations. In addition, driven exercise may also be characterized by intense difficult emotions if one is not able to exercise for any reason. Compensatory exercise was described as exercise that is partially or wholly intended to “make up” for calories consumed. Adaptive exercise was defined as any exercise that was neither driven nor compensatory.

Ecological Momentary Assessment Surveys. The current study included both signal-contingent (in response to a notification) and event-contingent (following engagement in an ED behavior) EMA surveys. Six EMA signals were semi-randomly spread out over the day such that participants received ~ 3 in the morning and ~ 3 in the afternoon/evening. Participants were also instructed to complete an EMA survey after engaging in an ED behavior such as binging, purging, or engaging in another compensatory behavior. All participants were required to complete EMA surveys for at least 7 days, however, participants could complete the surveys for up to 14 days, depending on the timing of their first treatment session.

Measures

Eating Pathology. The Eating Disorders Examination 17.0 [EDE; 17] was used to assess eating pathology over the previous 3 months. The EDE is a well-validated, semi-structured diagnostic interview and was administered by a trained rater.

Exercise. Exercise was assessed at each survey using the question “Have you exercised since the last survey?” If participants responded in the affirmative, they were then asked, “To what extent did you feel driven or compelled to exercise?”, and “To what extent did you exercise to compensate for eating?” Each of these questions was answered on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“Not at all”) to 5 (“Extremely”) and a maladaptive exercise episode was defined as endorsement of ≥ 3/5 on either question. These questions were created for this study, and the threshold of ≥ 3/5 for maladaptive exercise was selected based on previous studies [9].

Body Dissatisfaction. Body dissatisfaction was assessed at each survey using the question “Right now, how satisfied do you feel with your body shape or weight?” This question was answered on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“Not at all”) to 5 (“Extremely”).

Statistical analyses

Multilevel Models. All analyses were conducted using R [18] and used an alpha < 0.05 to determine statistical significance. To aid interpretability of the findings, state body dissatisfaction was recoded such that higher scores reflected greater state body dissatisfaction at a given survey prior to conducting analyses. Adjusted state body dissatisfaction responses ranged from 1 (“Extremely satisfied with body shape/weight”) to 5 (“Not at all satisfied”).

Due to the nested nature of our longitudinal data (observations within person), multilevel models used a continuous AR(1) structure to account for variance in the time between EMA surveys. Models which examined whether momentary elevations in state body dissatisfaction predicted engagement in exercise at the next survey used a binomial distribution with a logit link function due to the binary outcome. Additional models used a normal distribution to examine whether engagement in exercise predicted changes in state body dissatisfaction at the next survey. All models included between‐subject effects (i.e., participants’ mean level across the recording period) and within-subjects effects (i.e., state body dissatisfaction at that survey centered around each participant’s mean) for state body dissatisfaction. All between-subject variables were grand mean centered. Within-subject effects were centered within person. The current study focused on within-subjects effects as these reflect elevations in state body dissatisfaction above an individual’s mean level of body dissatisfaction across the recording period (see supplementary materials for full model parameters). In all analyses, we included fixed predictor variables and the random intercept of person and covaried for binge eating at the previous survey and BMI at baseline.

Trajectory Models. The within-day pre- and post-exercise trajectories of state body dissatisfaction were modeled separately using piecewise linear, quadratic, and cubic functions centered on the time at which the exercise episode occurred. This approach, which is referred to as mixed-effects polynomial regression models [19], was used because it allowed us to (1) model nonlinear trajectories, (2) model separate trajectories for pre-exercise and post-exercise temporal patterns, (3) model nonlinear relationships across time both at the individual and sample levels, (4) handle exercise episodes that occurred at differing time points, (5) include data with missing assessments, and (6) use data collected at differing time intervals.

Multilevel models in which momentary observations (Level 1) were nested within subjects (Level 2) were used to estimate linear (time prior/following the exercise), quadratic ([time prior/following the exercise]2), and cubic ([time prior/following the exercise]3) effects. To allow for the possibility of nonlinear trajectories, quadratic and cubic effects were estimated. The linear effect indicates whether the initial slope of the regression line (i.e., change in state body dissatisfaction proximal to an exercise episode) increased, decrease, or stayed flat. The quadratic effect indicates whether the initial slope (from the linear component) deflects downward or upward as it moves away from the intercept (i.e., the point of exercise). Thus, the quadratic estimate reflects the acceleration or deceleration in rate of change in state body dissatisfaction. The cubic effect captures possible changes in the rate of change of state body dissatisfaction occurring farthest from the intercept and indicates whether the initial deflection (from the quadratic component) intensifies or decelerates over time. Models specified a random intercept for subject and a common intercept for pre- and post-exercise trajectories.

Analyses examined whether the linear, cubic, and quadratic effects differed significantly from zero for pre-exercise trajectories. For post-exercise trajectories, analyses examined whether the linear, cubic, and quadratic effects of the post-exercise trajectory were significantly different from the pre-exercise trajectory (i.e., did the trajectory of change in state body dissatisfaction shift after the exercise episode).

To avoid confounding influences on the relationship between antecedent and consequent ratings of state body dissatisfaction, only the first exercise episode for each day was used when more than one episode was reported in a single day. To aid interpretation, effects for the linear, quadratic, and cubic functions were converted to standardized beta-weight values (β). All analyses were conducted within SPSS Version 26 using a first-order autoregressive covariance structure (AR1) to account for serial correlations. Maximum-likelihood estimation methods were used to estimate parameters.

Results

Sample descriptives

The current sample (82.9% female) included 58 adults with binge-spectrum eating disorders and mean age 44.07 years (SD = 13.78) and mean BMI = 35.31 kg/m2 (SD = 8.27). Participants primarily identified as Caucasian (86.4%) with others identifying as: African American (10.2%), or unknown or prefer not to say (3.4%); 13.5% identified as Hispanic or Latino. At baseline, participants endorsed an average of 24.23 (SD = 16.92) binge episodes and 6.70 (SD = 15.35) compensatory behaviors over the past month. Fifteen participants were diagnosed with Bulimia Nervosa (BN; 26.3%), 27 with Binge Eating Disorder (BED; 47.4%), and 15 with Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (26.3%; i.e., individuals with sub-threshold BN/BED who experienced subjective binge episodes).

EMA recordings and missing data

Average participant compliance (i.e., percent signal-contingent ratings completed for each prompt) was 87.9%, which is similar to previous EMA work within ED samples. Participants completed the protocol for an average of 11 days (SD = 2.79, range = 7–14) out of 13 (SD = 1.68, range = 7–14) prior to their first treatment session. Both signal-contingent and event-contingent recordings were used to capture state body dissatisfaction.

Exercise engagement

Participants reported a total of 448 exercise episodes, with an average of 7.7 (SD = 8.35) exercise episodes endorsed per participant over the recording period. Forty-six participants (79.3%) endorsed at least one episode of maladaptive exercise and participants with maladaptive exercise endorsed an average of 5.88 (SD = 8.67, range = 1–24) episodes of maladaptive exercise across the EMA period. See Table 1 for further description of exercise episode types. Only 7 episodes were reported as the second exercise episode within that day. A total of 325 antecedent state body dissatisfaction ratings (M = 0.78, SD = 0.79) and 705 consequent body dissatisfaction ratings (M = 0.66, SD = 0.76) were reported relative to within-day exercise episodes.

Prospective reciprocal associations between state body dissatisfaction and exercise

Momentary worsening of state body dissatisfaction at any given timepoint (i.e., greater than one’s average level of state body dissatisfaction) did not significantly predict engagement in exercise at the next nearest timepoint (β = − 0.117, S.E. = 0.172, p = 0.494, OR = 0.89). There was also no significant interaction between exercise type and momentary increases in state body dissatisfaction in predicting exercise engagement (β = 0.157, S.E. = 0.347, p = 0.650, OR = 1.17). Engagement in exercise at any given time point did not significantly predict momentary changes in state body dissatisfaction at the next nearest time point (β = − 0.010, S.E. = 0.036, p = 0.782), and exercise type did not moderate this relationship (β = 0.050, S.E. = 0.071, p = 0.481).

Trajectories of body dissatisfaction

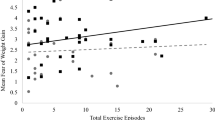

There was a significant positive linear (β = 0.012, SE = 0.031, p = 0.004) change in trajectory of state body dissatisfaction during hours preceding exercise. These findings indicate that during initial hours preceding exercise, state body dissatisfaction increased by 0.061 points, relative to their average state body dissatisfaction (see Table 2; Fig. 1).

Trajectory of state body dissatisfaction before and after an exercise episode. Higher ratings represent higher state body dissatisfaction. The graph depicts body dissatisfaction trajectories in the 4 h prior and following an exercise episode for simplicity, however, models estimated trajectories within each day surrounding exercise episodes. *(p < .05)

Discussion

The current study is one of the first to examine the prospective reciprocal associations between state body dissatisfaction and exercise, and whether this association is moderated by the type of exercise. This is also the first study to examine the trajectory of state body dissatisfaction pre- and post-exercise and to assess whether this trajectory is moderated by the type of exercise.

Unexpectedly, momentary worsening of state body dissatisfaction at any given timepoint did not prospectively predict engagement in exercise at the next nearest timepoint, and type of exercise did not moderate the prospective association between worse state body dissatisfaction and exercise engagement. While well-established theories and longitudinal studies have shown that among individuals with binge eating, high trait body dissatisfaction drives behaviors that are designed to control shape and weight, including exercise [20], our results suggest that momentary worsening of state body dissatisfaction may not be a momentary predictor of exercise. Similar results were observed in a recent study showing that daily, average state body dissatisfaction was not associated with engagement in either healthy or unhealthy weight control behaviors including exercise among healthy women [15]. One possible explanation for these results may be that exercise is a planned intentional behavior, which may reduce the likelihood of its occurrence in-the-moment as a behavior to cope with momentary worsening of state body dissatisfaction. Furthermore, it may be possible that individuals with binge eating choose to implement other ED behaviors in reaction to momentary increases in state body dissatisfaction. Indeed, emerging research has shown that momentary elevations in state body dissatisfaction prospectively predicts binge eating [16] and purging [21] in short term. An implication of these findings is that interventions for improving maladaptive exercise may not benefit from targeting momentary elevations in state body dissatisfaction. Future research is needed to elucidate other momentary factors (e.g., negative affect) that may drive exercise behaviors in short term as specific treatment targets.

Our results showed that engagement in exercise at any given timepoint did not prospectively predict momentary changes state body dissatisfaction at the next nearest timepoint. We also found that the type of exercise did not moderate the prospective association between exercise engagement and state body dissatisfaction. These results are contrary to the extant evidence from non-ED populations showing that engagement in exercise leads to improvements in body image [14]. One explanation may be that engagement in exercise increases body awareness which may maintain body dissatisfaction following exercise in individuals with binge eating. If replicated, our findings may suggest that among individuals with binge eating, state body dissatisfaction is not influenced by exercise engagement in the short term.

During the hours leading up to an exercise episode, state body dissatisfaction significantly increased during initial hours. However, in the following hours, the change in state body dissatisfaction was not significant. While we are limited in our methodology to explain the observed trajectory of change in state body dissatisfaction, future research should examine potential factors (e.g., momentary use of coping skills to manage increases in state body dissatisfaction) that may influence the changes in state body dissatisfaction ratings over hours preceding an exercise episodes. State body dissatisfaction did not significantly improve in the hours following the exercise episode. These results along with those mentioned above, may preliminarily suggest that state body dissatisfaction does not improve after an exercise engagement, likely due to higher trait body dissatisfaction among individuals with binge eating. If replicated in larger samples, our findings may suggest that clinicians should consider explicitly targeting assumption surrounding the perceived role of exercise in improving state body dissatisfaction when addressing exercise in treatment. Contrary to our hypothesis, the type of exercise did not moderate the association between pre- or post-exercise change in state body dissatisfaction over time indicating the type of exercise may not influence the change in state body dissatisfaction over time pre- or post-exercise episodes.

Strength and limits

While the EMA methodology used in this study represents a robust test of hypotheses, the results of the current study should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, because of the paucity of research on the assessment of exercise behaviors in eating disorders sample using EMA approach, we created preliminary questions which were based on clinical experience and were not validated. Future research should aim to develop valid EMA measures of self-reported exercise engagement or use physiological sensors to detect exercise engagement to overcome these limitations. Second, given the small number of episodes of different types of maladaptive exercise (driven n = 119, compensatory n = 9, driven and compensatory n = 100), we were unable to assess the differential prospective associations between state body dissatisfaction and type of maladaptive exercise that would have provided additional detail regarding which type of exercise is most strongly related to momentary increases in state body dissatisfaction. Third, despite existing evidence suggesting that reactivity to EMA methodology is limited [22], repeated assessments may have caused individuals to pay more attention to their bodies and contributed to greater body image reactivity. Last, there were several unmeasured variables that could help us further understand the nature of relationship between state body dissatisfaction and exercise. For example, some individuals with binge eating may plan to exercise much later, even the next day, to mitigate the perceived consequences of binge eating (e.g., guilt, weight gain), which could partially influence the association between state body dissatisfaction and exercise. As such, future research would benefit from exploring other factors (e.g., advance planning of exercise, negative affect, fear of weight gain, experience of feeling fat) as potential factors impacting the association between state body dissatisfaction and exercise to intervene on them more deliberately in treatment. In addition, it is possible that trait levels of body dissatisfaction may change associations between state body dissatisfaction and exercise engagement. As such, future studies should examine overall associations between trait-level body dissatisfaction and exercise engagement using validated measures such as the EDE.

What is already known on this subject?

Extant literature has found that among individuals who engaged in frequent exercise (i.e., at least three times per week), high baseline motivation to control appearance and weight predicted increases in state body dissatisfaction following exercise [13]. Another cross-sectional study suggests that in-lab exercise engagement produces improvements in body dissatisfaction, especially in participants with higher body dissatisfaction [14]. However, the sample used in this study was non-clinical, thus we do not understand if these associations hold true within a clinical sample.

What this study adds?

Our results suggest that momentary increases state body dissatisfaction is not a momentary predictor of exercise, and that engagement in exercise does not predict lower state body dissatisfaction at the following timepoint. Exercise engagement in individuals with binge eating may be maintained by factors others than state body dissatisfaction.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub

Claudino AM et al (2019) The classification of feeding and eating disorders in the ICD-11: results of a field study comparing proposed ICD-11 guidelines with existing ICD-10 guidelines. BMC Med 17(1):1–17

Hausenblas HA, Downs DS (2002) How much is too much? The development and validation of the exercise dependence scale. Psychol Health 17(4):387–404

Meyer C et al (2011) Compulsive exercise and eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 19(3):174–189

Monell E et al (2018) Running on empty–a nationwide large-scale examination of compulsive exercise in eating disorders. J Eat Disord 6(1):11

Smith AR et al (2013) Exercise caution: Over-exercise is associated with suicidality among individuals with disordered eating. Psychiatry Res 206(2–3):246–255

Solenberger SE (2001) Exercise and eating disorders: a 3-year inpatient hospital record analysis. Eat Behav 2(2):151–168

Vall E, Wade TD (2015) Predictors of treatment outcome in individuals with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord 48(7):946–971

Lampe EW et al (2021) Characterizing reasons for exercise in binge-spectrum eating disorders. Eat Behav 43:101558

O’Hara CB et al (2016) The effects of acute dopamine precursor depletion on the reinforcing value of exercise in anorexia nervosa. PLoS ONE 11(1):e0145894

Chubbs-Payne A et al (2021) Attitudes toward physical activity as a treatment component for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: an exploratory qualitative study of patient perceptions. Int J Eat Disord 54(3):336–345

Hausenblas HA, Fallon EA (2006) Exercise and body image: a meta-analysis. Psychol Health 21(1):33–47

LePage ML, Crowther JH (2010) The effects of exercise on body satisfaction and affect. Body Image 7(2):124–130

Vocks S et al (2009) Effects of a physical exercise session on state body image: The influence of pre-experimental body dissatisfaction and concerns about weight and shape. Psychol Health 24(6):713–728

Sala M et al (2020) State body dissatisfaction predicts momentary positive and negative affect but not weight control behaviors: an ecological momentary assessment study. Eat Weight Disord 26(6):1957–1962

Srivastava P et al (2021) Do momentary changes in body dissatisfaction predict binge eating episodes? An ecological momentary assessment study. Eat Weight Disord 26(1):395–400

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, O’Connor M (1993) The eating disorder examination. Int J Eat Disord 6:1–8

Team, RC (2013) R: A language and environment for statistical computing

Hedeker D, Gibbons RD (2006) Longitudinal data analysis, vol 451. John Wiley & Sons

Neumark-Sztainer D et al (2006) Does body satisfaction matter? Five-year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. J Adolesc Health 39(2):244–251

Mason TB et al (2018) Examining a momentary mediation model of appearance-related stress, anxiety, and eating disorder behaviors in adult anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 23(5):637–644

Heron KE, Smyth JM (2013) Is intensive measurement of body image reactive? A two-study evaluation using ecological momentary assessment suggests not. Body Image 10(1):35–44

Funding

Dr. Manasse is supported by an award from the National Institute of Health (K23DK124514).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by the Drexel University Institutional Review Board.

Consent to participate

All the participants provided informed consent for participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Srivastava, P., Lampe, E.W., Wons, O.B. et al. Understanding momentary associations between body dissatisfaction and exercise in binge-spectrum eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord 27, 2193–2200 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01371-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01371-0