Abstract

Purpose

Obligatory exercise is characterized by continued exercise despite negative consequences, and intense negative affect when unable to exercise. Research suggests psychosocial differences between individuals that exercise in an obligatory manner and those that do not. It also has been speculated that obligatory exercise may serve coping and affect regulation functions, yet these factors have not been routinely examined in community women with poor body image. The purpose of the current study was to investigate psychosocial differences between obligatory and non-obligatory exercisers, and to examine the use of obligatory exercise as an avoidant coping strategy in a sample of women with poor body image.

Methods

Women (n = 70) seeking treatment for body dissatisfaction were divided into obligatory and non-obligatory exercise groups based on their scores on the Obligatory Exercise Questionnaire. Participants then completed an assessment battery about eating pathology, body image, reasons for exercise, coping strategies, and negative affect.

Results

Independent t test analyses indicated that obligatory exercisers had significantly greater eating disorder symptomatology, avoidant coping, and appearance- and mood-related reasons for exercise than non-obligatory exercisers. Multiple regression analyses revealed that eating disorder symptomatology and avoidant coping were significant predictors of obligatory exercise.

Conclusions

There are distinct psychosocial differences between women with poor body image who exercise in an obligatory fashion and those who do not. The current study suggests that obligatory exercise may serve as an avoidant coping strategy for women with poor body image. Enhancing healthy coping strategies may be an important addition to body image improvement programs.

Level of evidence

V, cross-sectional descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many women are dissatisfied with the size and shape of their bodies and seek to alter them through exercise [1, 2]. Although there are many benefits of exercise, it has the potential to become unhealthy, especially when motivated by weight and shape concerns [3,4,5]. Indeed, unhealthy exercise frequently is present prior to the onset of eating disorders, is often described in the symptomatology of eating disorders, especially anorexia nervosa, and has long been viewed as a problematic behavior for a subset of patients with eating disorders [6,7,8]. Unhealthy exercise also is a common compensatory behavior used to counteract the effects of binge eating among individuals with bulimia nervosa [9], and has been associated with the condition called orthorexia nervosa, which is characterized as an obsession with healthy eating [10].

Unhealthy exercise can be defined both quantitatively (excessive) and qualitatively (obligatory) [11]. Excessive exercise is characterized by exaggerations in intensity, frequency, and duration beyond the point of being health promoting [12]. Obligatory exercise entails exercising even when negative consequences (e.g., injury) are present, and experiencing intense negative affect when unable to exercise [13,14,15,16,17]. Overall, obligatory exercise tends to be the more informative and agreed-upon measure of unhealthy exercise. Previous research suggests that the quality of one’s relationship to exercise is associated with greater psychological distress and eating pathology relative to amount of exercise [4, 11, 17,18,19], and exercise in response to negative affect is conceptualized as “at-risk” exercise irrespective of amount of time spent exercising [20].

Previously, researchers have investigated differences between individuals who engage in obligatory exercise and those who do not. Obligatory exercisers have a lower body mass index (BMI) yet more negative body images and patterns of eating pathology than non-obligatory exercisers [21,22,23]. They also report receiving more negative familial messages about shape, weight, and exercise [23]. Other studies found associations between obligatory exercise and lower psychosocial functioning, increased anxiety, and obsessive–compulsive traits [5, 18, 24, 25]. However, one of the most important hallmarks of obligatory exercise is its use as an affect regulation method [22,23,24]. Taranis and Meyer suggested that obligatory exercise helped individuals avoid negative emotional consequences similarly to other eating-disordered methods used for affect regulation (e.g., purging) [19]. Other studies also have confirmed obligatory exercise patterns among individuals that reported exercising to address negative affect [5, 25].

In addition to strongly predicting obligatory exercise, affect regulation is closely related to certain coping strategies [26]. For example, Zalewski and colleagues found that individuals with less emotional regulation used avoidance coping strategies more frequently than those who were better able to regulate their emotions [27]. Perhaps not surprisingly then, obligatory exercise is sometimes considered an avoidant coping strategy [19]. Indeed, in clinical eating disorder populations, obligatory exercise has often been viewed, in part, as a coping strategy to aid in affect regulation or to help avoid negative thoughts and feelings [7, 19, 28, 29]. However, this theory does not appear to have been tested empirically.

In summary, obligatory exercise in non-clinical samples is frequently associated with increased eating disorder symptoms, and some evidence suggests its use in affect regulation. Several authors have suggested that obligatory exercise serves a coping function, yet this hypothesis has not been tested. Previous studies also have been limited by the absence of specific measures of overall negative affect, coping strategies, or obligatory exercise, and the exclusive recruitment of college students [5, 19, 20, 24, 25].

The present study

The current study examined the relationship between obligatory exercise and negative affect, general coping styles, and explicit reasons given for exercising in a community sample of women with poor body image who were seeking body image treatment. Understanding the relationship between body image and obligatory exercise is important, given that poor body image is among the most robust predictors for the development of eating disorders [30]. Including a sample of women with poor body image that only differed on obligatory exercise allowed for a better understanding of the function of obligatory exercise and its relationship to eating pathology. The current study improved upon the measures of negative affect used in several studies by including standardized instruments. Additionally, we included a standard measure of coping and recruited an ethnically diverse sample.

We hypothesized that obligatory exercisers would have greater eating disorder symptomatology, higher levels of negative affect, an avoidance-oriented coping style, and appearance- and mood-regulatory reasons for exercise. Additionally, we examined the relative contribution of each of these psychosocial variables in predicting obligatory exercise, and hypothesized that avoidance-oriented coping and eating disorder symptomatology would be significant predictors of obligatory exercise.

Methods

Participants

Participants were a community sample of women who responded to flyers and newspaper advertisements for a free body image treatment workshop that was part of a research project. The project was for normal weight women who were dissatisfied with their bodies and who wanted to feel better about their shape and size. Inclusion criteria included: (1) age 18 or over; (2) 80–120% of ideal body weight as determined by the Metropolitan Life Insurance tables, and (3) significant body image disturbance, as operationalized by a score ≤ 23 on the appearance evaluation subscale of the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire [31, 32].

A total of 223 telephone screens were conducted, which resulted in excluding women who were outside the designated weight range (n = 12) or had schedule conflicts (n = 3). Another 40 individuals excluded themselves, stating that the study appeared time-consuming (n = 33), or that they wanted a project that promoted weight loss (n = 7). The remaining 168 women were scheduled for an assessment appointment. 61 women failed to attend the appointment and one terminated her participation during the assessment, resulting in 106 women who completed the assessment battery. 18 participants scored above the cutoff of 23 on the Appearance Evaluation subscale of the MBSRQ [33]. Since this suggested that these women were not notably distressed about their bodies, they were not included in study analyses [33]. Additionally, 17 women met diagnostic criteria for a past or current ED diagnosis based on the eating disorders module of the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID) for DSM-IV-TR [34]. These women were removed from the study because we were particularly interested in a non-diagnosable community sample of women who were seeking treatment for body image distress.

Measures

Obligatory Exercise Questionnaire (OEQ) [35] This 20-item scale assesses exercise status and obligatory exercise behaviors and cognitions. Participants assess their agreement with each statement on a 1 (“never”) to 4 (“always”) scale. Those who have a total score above 50 are labeled as obligatory exercisers, and those who score ≤ 50 are considered non-obligatory exercisers [11, 30]. In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) [36] This 34-item instrument asks participants to indicate how they feel about their body and body parts. It uses a 6-point Likert scale (1 = “never”, 6 = “always”). Higher scores indicate greater body shape concern. Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was 0.94.

Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) [37] This 26-item questionnaire assesses anorexic and bulimic behaviors and attitudes. Participants indicate how true the statements are for them on a 6-point Likert scale, with choices of “never” (0), “rarely” (0), “sometimes” (0), “often” (1), “very often” (2), and “always” (3). Items are summed, with higher scores indicating more disordered eating. The reliability coefficient in our sample was 0.85.

Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS) [38] This 48-item inventory consists of three major subscales task-oriented, avoidance-oriented, and emotion-oriented coping. Task-oriented coping involves attempting to solve the problem. Avoidance-oriented coping indicates the tendency to handle a stressful situation by avoiding it altogether, and emotion-oriented coping focuses on reducing the negative emotions elicited by stress. Using a 5-point Likert scale, individuals indicate how likely they are to engage in each behavior when faced with a stressful situation. Higher scores within a subscale indicate stronger use of that coping strategy. In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the task-oriented, avoidance-oriented, and emotion-oriented coping subscales were 0.92, 0.86, and 0.89, respectively.

Reasons for Exercise Inventory (REI) [39] This 24-item inventory determines motivations for exercising. Items are rated on a scale of 1 (“not at all important”) to 7 (“extremely important”). The REI yields 3 domain scales Appearance Enhancement, Health/Fitness, and Mood/Enjoyment. In our sample Cronbach’s alpha was 0.72 for the Appearance Enhancement scale, 0.88 for Health/Fitness scale, and 0.77 for the Mood/Enjoyment scale.

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI) [40] This 21-item measure of depression indicates severity of symptoms on a 0–3 Likert scale. In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [41] The STAI consists of two 20-item subscales; state anxiety and trait anxiety. Participants rate how accurately each statement reflects their anxiety feelings on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all”, 4 = “very much so”). Higher scores indicate more anxiety. Cronbach’s alpha in our sample was 0.93 for state anxiety and 0.93 for trait anxiety.

Procedure

The current study was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. After providing informed consent, participants completed an assessment battery. All participants were debriefed upon completing the assessment battery. As part of their incentive for participating in the study, individuals were given the opportunity to participate in a 4-h cognitive–behavioral body image treatment workshop with a clinical psychologist specializing in eating disorders [42].

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24 [43]. One participant had a missing value on one of the variables of interest; mean substitution was used to estimate that single value. Comparisons in psychosocial variables were examined using independent t tests and Chi-square. Levene’s test was used to correct for any violations of the assumption of heterogeneity. Cohen’s d was used as a measure of effect size. Prediction of obligatory exercise was examined by multiple linear regression. Squared semi-partial correlations were examined to determine the relative contribution of each predictor.

Previous research has found medium-to-large effects for the association between obligatory exercise and body image [20, 30], eating disorder symptomatology [15, 25, 35], and negative affect [25] in non-clinical samples. We calculated power using an estimated effect size of d = 0.40 and a sample size of 70. These analyses indicated that our estimated power would be 0.95 for this study.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Obligatory and non-obligatory exercisers did not significantly differ in age, number of years of education, or BMI. However, obligatory exercisers reported having significantly fewer children compared to non-obligatory exercisers. Chi-square analyses indicated no significant difference in marital status or ethnic/racial identity (see Table 1).

Body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptomatology

As expected given the recruitment requirements, both types of exercisers reported moderate levels of body image concern on the BSQ, and they did not differ significantly from each other. Obligatory exercisers had significantly higher EAT scores compared to the non-obligatory exercisers, indicating more eating disorder concerns (see Table 2).

Reasons for exercise

Obligatory and non-obligatory exercisers also differed in their reasons for exercise. On the REI, obligatory exercisers exercised more for appearance enhancement-related reasons and mood/enjoyment-related reasons compared to non-obligatory exercisers. There was no significant difference in health/fitness-related reasons for exercise (see Table 2).

General coping strategies and negative affect

Obligatory exercisers reported engaging in more avoidance-oriented coping compared to non-obligatory exercisers, though they did not differ in emotion-oriented or task-oriented coping on the CISS. Contrary to our original hypotheses, the obligatory and non-obligatory exercisers did not significantly differ on measures of depression, state anxiety, or trait anxiety (see Table 2).

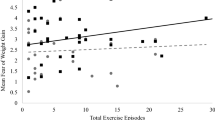

Prediction of obligatory exercise

All predictor variables that were significantly different between the obligatory and non-obligatory exercises were entered in a multiple linear regression (see Table 3). The overall model was significant and accounted for 44.2% of the variance in OEQ scores F(4, 65) = 12.854, p < 0.001. Two variables, eating disorder symptomatology and avoidance-oriented coping, emerged as significant predictors of obligatory exercise. These variables accounted for 7.2% and 7.0% of the variance in OEQ scores, respectively. The regression analyses also were run including demographic (age, BMI, education, and number of children) and other psychological predictors (depression, anxiety, body dissatisfaction, health-related reasons for exercise, and task and emotion-oriented coping) in the model. The overall model accounted for 51.3% of the variance in OEQ scores F(15, 69) = 3.795, p < 0.001. The same two variables, eating disorder symptomatology (β = 0.45, p = 0.004, sr2 = 0.083) and avoidance-oriented coping (β = 0.35, p = 0.016, sr2 = 0.056), were significant predictors of obligatory exercise in this model.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to understand differences in eating disorder pathology, coping strategies, reasons for exercise, and affect among obligatory and non-obligatory exercisers from an ethnically diverse community sample of women with poor body image. Our results indicate that even when controlling for body dissatisfaction, obligatory exercisers endorsed significantly more eating disorder symptomatology, avoidant coping strategies, and appearance- and mood-related reasons for exercise than did non-obligatory exercisers. Eating disorder symptomatology and avoidance-oriented coping were the strongest predictors of obligatory exercise.

Differences in demographic variables

Obligatory and non-obligatory exercisers were similar on all demographic variables except number of children. This finding may be explained by previous research suggesting that women with children perceive more barriers to exercise, such as a lack of time due to childcare and other family/household responsibilities, compared to women without children [44]. Contrary to previous findings that obligatory exercisers have lower BMIs, there was no difference in BMI between obligatory and non-obligatory exercisers [21]. Potentially this may be explained partially by the inclusionary criteria, which required that participants be within 80–120% of their ideal body weight.

Differences in body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptomatology

The obligatory exercisers reported significantly higher eating disorder symptoms compared to the non-obligatory exercisers, with the former scoring close to the established cutoff indicating eating disorder risk [45]. This finding supports research which suggests that obligatory exercisers have greater eating pathology compared to non-obligatory exercisers in both clinical and non-clinical samples [19, 23, 46]. Furthermore, it expands upon previous research by parceling out the contributions of body image. Overall, obligatory exercise seems to be a key feature in helping predict eating disorder concern, beyond that of body image concern, in a sample of women from the community.

Differences in reasons for exercise

Obligatory exercisers were more likely than their non-obligatory counterparts to report exercising for appearance- and mood-related reasons. Previous research found that community women who exercised for appearance or body shape reasons had higher levels of eating disorder pathology and poorer quality of life than women who exercised for other reasons [17]. Thome and Espelage found that weight-related reasons for exercise mediated the relationship between exercise and eating disorder pathology [5]. Previous research also found that mood-related reasons for exercise were associated with greater levels of eating pathology [16, 25]. In summary, our findings support the previous literature, which suggests that exercising for appearance or mood reasons is often associated with compulsivity and eating disorders.

Differences in general coping strategies and psychosocial functioning

Use of avoidant coping strategies was significantly greater among the obligatory exercisers compared to the non-obligatory exercisers. Thus, obligatory exercise may serve a unique psychological function, specifically avoidance of negative thoughts or feelings, as exercise preoccupation may allow individuals to avoid dealing with daily stressors that would otherwise produce intense emotional responses [47, 48]. This study provides further evidence that obligatory exercise should be construed as an avoidance behavior and is in line with previous research linking avoidance coping and maladaptive exercise beliefs [8, 49]. Meyer and colleagues further suggest that compulsive exercisers experience psychological dependence and continue to exercise in an effort to avoid not only stressors, but also affective withdrawal symptoms associated with dependence [8]. Additionally, this may help explain a link between obligatory exercise and eating disorders, given that disordered eating attitudes and behaviors often are associated with an avoidant coping style [50, 51].

Neither depression nor anxiety significantly differed between obligatory and non-obligatory exercisers, which is in contrast to previous findings with clinical samples showing that compulsive exercisers experience higher levels of negative affect [7, 8, 46]. Two studies with non-clinical samples found elevated rates of anxiety in the form of obsessive–compulsive traits in obligatory exercisers, but more global anxiety problems were either not measured or not found, and depressed mood was not examined at all [5, 21]. Importantly, the current sample in general showed elevated rates of both anxiety and depression, so it is unclear how this might have influenced the relationship with obligatory exercise.

Prediction of obligatory exercise

This study found that eating disorder symptomatology and avoidance-oriented coping were significant predictors of OEQ scores. Previous research has long described the association between eating disorder symptomatology and obligatory exercise [6, 7]. However, this appears to be the first study to demonstrate that a reliance on avoidance-oriented coping predicts obligatory exercise levels in a community sample of women with poor body image. This finding suggests that individuals who rely on that coping strategy are more likely to exercise in an obligatory fashion, and suggests that obligatory exercise can be conceptualized as an avoidance behavior. Clinicians treating poor body image should focus on expanding clients’ repertoire of coping strategies, such as by increasing task-oriented strategies.

Limitations, strengths, and future directions

This study was cross-sectional in design, and responses were based on self-report. Our sample was limited to women seeking a body image intervention, and therefore our results may not generalize to non-treatment seeking populations. Finally, the sample size was small, and effect sizes were smaller than hypothesized a priori, suggesting that some of our analyses may have been underpowered. Future work should replicate these findings in a larger sample. The small sample also did not allow for tests of measurement invariance across ethnicity, and the validity of the various instruments with the Hispanic women in the study could not be tested [52, 53]. The strengths of the study were its recruitment of a treatment-seeking, ethnically diverse community sample of women with elevated body dissatisfaction, which allowed us to disentangle three highly related constructs (eating pathology, poor body image, and obligatory exercise). This study had additional unique features, as it specifically examined coping style and stated reasons for exercising.

Future research should replicate these findings in larger samples and in samples of individuals seeking treatment for an eating disorder. Additionally, the current study is only able to suggest that an overall more avoidant coping strategy is associated with obligatory exercise. It will be important to use additional assessment strategies, such as ecological momentary assessment, to understand how obligatory exercise, specifically, serves as an avoidant coping strategy (i.e., to decrease negative affect). Mediational analyses also should be used to examine other factors, such as anxiety or depression, which may help explain the relationship between avoidant coping and obligatory exercise. Finally, although beyond the scope of this study, it is widely known that there are many benefits of exercise, especially to improve health, improve mood, and to cope with stress [3, 20]. Yet, it is unclear at what point exercise transitions from being an effective to being a problematic coping strategy. Future work needs to continue to examine at what point this transition occurs, in order to provide recommendations that help women with poor body image exercise in ways that serve to effectively cope with stress without resulting in problematic exercise behaviors.

Conclusions

In general, obligatory exercisers reported greater eating disorder pathology, use of avoidant coping strategies, and appearance- and mood-related reasons for exercise than did non-obligatory exercisers. Eating disorder symptomatology and avoidant-oriented coping were the strongest predictors of obligatory exercise. Although previously speculated, this seems to be the first study to establish a link between avoidance-oriented coping and obligatory exercise. Thus, it appears as if healthy, problem-focused coping strategies for dealing with distress and negative mood should be included in body image improvement programs and when addressing obligatory exercise.

References

Fallon EA, Harris BS, Johnson P (2014) Prevalence of body dissatisfaction among a United States adult sample. Eat Behav 15:151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.11.007

Kruger J, Galuska DA, Serdula MK, Jones DA (2004) Attempting to lose weight: specific practices among US adults. Am J Prev Med 26:402–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2004.02.001

Penedo FJ, Dahn JR (2005) Exercise and well-being: a review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Curr Opin Psychiatry 18:189–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yco.2004.09.001

Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C (2006) An update on the definition of “excessive exercise” in eating disorders research. Int J Eat Disord 39:147–153. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20214

Thome JL, Espelage DL (2007) Obligatory exercise and eating pathology in college females: Replication and development of a structural model. Eat Behav 8:334–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.11.009

Davis C (1997) Body image, exercise, and eating behaviors. In: Fox K (ed) The physical self: From motivation to well-being. Human Kinetics, Champaign, pp 143–174

Peñas-Lledó E, Vaz Leal FJ, Waller G (2002) Excessive exercise in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: relation to eating characteristics and general psychopathology. Int J Eat Disord 31:370–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10042

Meyer C, Taranis L, Goodwin H, Haycraft E (2011) Compulsive exercise and eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 19:174–189. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1122

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th edn). American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington

Rudolph S (2017) The connection between exercise addiction and orthorexia nervosa in German fitness sports. Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0437-2

Adkins EC, Keel PK (2005) Does “excessive” or “compulsive” best describe exercise as a symptom of bulimia nervosa? Int J Eat Disord 38:24–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20140

Davis C, Fox J (1993) Excessive exercise and weight preoccupation in women. Addict Behav 18:201–211

Coen SP, Ogles BM (1993) Psychological characteristics of the obligatory runner: a critical examination of the anorexia analogue hypothesis. J Sport Exerc Psychol 15:338–354. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.15.3.338

Steffen JJ, Brehm BJ (1999) The dimensions of obligatory exercise. Eat Disord 7:219–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640269908249287

Boyd C, Abraham S, Luscombe G (2007) Exercise behaviours and feelings in eating disorder and non-eating disorder groups. Eur Eat Disord Rev 15:112–118. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.769

Mond JM, Calogero RM (2009) Excessive exercise in eating disorder patients and in healthy women. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 43:227–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670802653323

Macfarlane L et al (2016) Identifying the features of an exercise addiction: a Delphi study. J Behav Addict 5:474–484. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.060

Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJ (2004) Relationships between exercise behaviour, eating-disordered behaviour and quality of life in a community sample of women: when is exercise ‘excessive?’ Eur Eat Disord Rev 12:265–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.579

Taranis L, Meyer C (2011) Associations between specific components of compulsive exercise and eating-disordered cognitions and behaviors among young women. Int J Eat Disord 44:452–458. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20838

Freimuth M, Moniz S, Kim SR (2011) Clarifying exercise addiction: Differential diagnosis, co-occurring disorders, and phases of addiction. Int J Res Public Health 8:4069–4081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8104069

Smith JE, Wolfe BL, Laframboise DE (2001) Body image treatment for a community sample of obligatory and non-obligatory exercisers. Int J Eat Disord 30:375–388. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.1099

Bratland-Sanda S, Martinsen EW, Rosenvinge JH, Rø Ø, Hoffart A, Sundgot-Borgen J (2011) Exercise dependence score in patients with longstanding eating disorders and controls: the importance of affect regulation and physical activity intensity. Eur Eat Disord Rev 19:249–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.971

Lease HJ et al (2016) My mother told me: the roles of maternal messages, body image, and disordered eating in maladaptive exercise. Eat Weight Disord 21:469–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0238-4

Thome J, Espelage DL (2004) Relations among exercise, coping, disordered eating, and psychological health among college students. Eat Behav 5:337–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.04.002

De Young KP, Anderson DA (2010) Prevalence and correlates of exercise motivated by negative affect. Int J Eat Disord 43:50–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20656

Compas BE, Jaser SS, Dunbar JP, Watson KH, Bettis AH, Gruhn MA, Williams EK (2014) Coping and emotion regulation from childhood to early adulthood: points of convergence and divergence. Aust J Psychol 66:71–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12043

Zalewski M, Lengua LJ, Wilson AC, Trancik A, Bazinet A (2011) Associations of coping and appraisal styles with emotion regulation during preadolescence. J Exp Child Psychol 110:141–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2011.03.001

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R (2003) Cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther 41:509–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8

Lawson R, Waller G, Lockwood R (2007) Cognitive content and process in eating disordered patients with obsessive-compulsive features. Eat Behav 8:305–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.11.006

Stice E (2001) A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology: mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. J Abnorm Psychol 110:124–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.124

Metropolitan Life Insurance Company (1983). 1983 height and weight tables. Stat Bull Metrop Life Found 6:3–9

Brown T, Cash T, Mikulka P (1990) Attitudinal body-image assessment: Factor analysis of the Body-Self Relations Questionnaire. J Pers Assess 55:889–897. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.1990.9674053

Cash TF (1994) Users’ manual for the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire. Old Dominion University, Norfolk

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gizzon M, Williams JBW (2002) Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-RT axis I disorders. Biometrics Research, New York

Pasman, L, Thompson JK (1998) Body image and eating disturbance in obligatory runners, obligatory weightlifters, and sedentary individuals. Int J Eat Disord 7:759–769. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198811)7:6<759::AID-EAT2260070605>3.0.CO;2-G

Cooper PJ, Taylor MJ, Cooper Z, Fairburn CG (1987) The development and validation of the body shape questionnaire. Int J Eat Disord 6:485–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198707)6:4<485::AID-EAT2260060405>3.0.CO;2-O

Garner DM, Garfinkel PE (1979) The Eating Attitudes Test: An index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med 9:273–279. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700030762

Endler NS, Parker JDA (1999) Coping inventory for stressful situations (CISS) manual, 2nd edn. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto

Silberstein LR, Striegel-Moore RH, Timko C, Rodin J (1988) Behavioral and psychological implications of body dissatisfaction: do men and women differ? Sex Roles 19:219–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00290156

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK (1996) Beck depression inventory-II. Psychological Corporation, Texas

Spielberger C (1983) Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press, California

Cash T (2008) The body image workbook: an eight-step program for learning to like your looks. New Harbinger Publications, California

IBM Corp (2016) IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. IBM, New York

Verhoef MJ, Love EJ (1994) Women and exercise participation: the mixed blessing of motherhood. Health Care Women Int 15:297–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399339409516122

Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE (1982) The Eating Attitudes Test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med 12:871–878. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700049163

Shroff H, Reba L, Thornton LM, Tozzi F, Klump KL, Berrettini WH et al (2006) Features associated with excessive exercise in women with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 39:454–461. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20247

Borkovec TD (2002) Life in the future versus life in the present. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 9:78–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.9.1.76

Roemer L, Orsillo SM (2002) Expanding our conceptualization of and treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: integrating mindfulness/acceptance-based approaches with existing cognitive behavioral models. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 9:54–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.9.1.54

Loumidis K, Wells A (2001) Exercising for the wrong reasons: relationships among eating disorder beliefs, dysfunctional exercise beliefs and coping. Clin Psychol Psychother 8:416–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.298

Sherwood NE, Crowther JH, Wills L, Ben-Porath YS (2000) The perceived function of eating for bulimic, subclinical bulimic, and non-eating disordered women. Behav Ther 31:777–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(00)80044-1

VanBoven AM, Espelage DL (2006) Depressive symptoms, coping strategies, and disordered eating among college women. J Couns Dev 84:341–348. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2006.tb00413.x

Belon KE, McLaughlin EA, Smith JE, Bryan AD, Witkiewitz K, Lash DN, Winn JL (2015) Testing the measurement invariance of the Eating Disorder Inventory in non-clinical samples of Hispanic and Caucasian women. Int J Eat Disord 48:262–270. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22286

Belon KE, Smith JE, Bryan AD, Lash DN, Winn JL, Gianini LM (2011) Measurement invariance of the Eating Attitudes Test-26 in Caucasian and Hispanic women. Eat Behav 12:317–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.07.007

Funding

This study was not supported by funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Serier, K.N., Smith, J.E., Lash, D.N. et al. Obligatory exercise and coping in treatment-seeking women with poor body image. Eat Weight Disord 23, 331–338 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0504-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0504-3