Abstract

Purpose

The present study examined the predictive value of early maladaptive schema (EMS) domains on the diagnosis of binge eating disorder (BED).

Methods

Seventy obese patients seeking treatment for weight loss were recruited and allocated to either group 1 (obese) or group 2 (BED-obese) according to clinical diagnosis. Both groups underwent psychometric assessment for EMS (according to the latest four-factor model), eating and general psychopathologies. Logistic regression analysis was performed on significant variables and BED diagnosis.

Results

In addition to showing higher values on all clinical variables, BED-obese patients exhibited significantly higher scores for all four schema domains. Regression analysis revealed a 12-fold increase in risk of BED with ‘Impaired Autonomy and Performance’. Depression did not account for a higher risk.

Conclusions

Impaired Autonomy and Performance is associated with BED in a sample of obese patients. Schema therapy should be considered a potential psychotherapy strategy in the treatment of BED.

Level of evidence

Level III, case–control study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Binge eating disorder (BED) is the most common eating disorder (ED), with a lifetime prevalence of 3% in the general population [1, 2] and up to 50% in clinical samples of obese subjects accessing weight loss services [3]. Its high prevalence, the psychiatric [4, 5] and medical [6] comorbidities and the lack of evidence-based pharmacological treatment have all contributed to capture clinical and scientific attention.

To date, psychotherapy, and in particular cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), is the most highly rated treatment approach for BED, even though the data indicate that many individuals either relapse or do not fully recover after treatment in the long term [7,8,9]. According to some authors, CBT is ‘necessary, but not sufficient’ to successfully treat EDs because it focuses on dysfunctional thoughts about weight and shape while neglecting other longitudinal factors related to the onset and maintenance of EDs [10]. As a consequence, it has been argued that mixed interventions that consider different pathological domains could optimise efficacy outcomes in BED [11].

Schema therapy (ST), the therapeutic focus of which are early maladaptive schemas (EMS) [12], belongs to the third wave of CBT for the treatment of complex disorders and has already been proposed for the treatment of BED [11]. EMS are negative representations of oneself, others and the environment that develop during childhood and are assumed to be enduring, resistant to change, self-confirmatory and self-perpetuating [13]. Young identified 18 EMS clustered within five domains [12]. More recently, a four-factor model (i.e., Disconnection and Rejection, Impaired Autonomy and Performance, Excessive Responsibility and Standards, Impaired Limits) has been proposed as the most appropriate in relation to childhood experiences of need-thwarting parenting, having a better model fit [14]. The schema-focused model of eating disorders is largely supported by the literature [15]. According to this model, the EMS subtend core ED psychopathology, where eating behaviours serve to avoid (for restrictive EDs) or relieve (for bingeing EDs) emotions after a schema has been triggered [10]. ST has also proved efficacious in treating the comorbidities often found in patients with EDs [16], such as depression.

Bingeing has been correlated with several schemas (i.e., ‘vulnerability to harm’, ‘social isolation’, ‘dependence–incompetence’, ‘enmeshment and unrelenting standards’) [17, 18], and above all ‘emotional inhibition’. A small number of studies have explored EMS in BED [17,18,19]. According to Pugh [15], BED is associated with higher scores on ‘dependence–incompetence’ and ‘emotional inhibition’ schemas: that is, BED patients do not trust in their ability to function autonomously and successfully achieve goals; they also experience difficulty in communicating emotions because of fear of being embarrassed, judged and rejected [20].

Combined, these results suggest that ST may be a promising therapy for BED. However, there is a lack of consistency across studies. This, and several methodological biases or limitations, has so far prevented a scientific consensus from being reached. In some studies, binge eating has been assessed with different tools, such as diary reports [19, 21], general eating pathology subscales [20, 22] or questionnaires built on DSM criteria [23]. In others, schemas have been studied in association with bulimic habits rather than BED diagnosis [17, 19, 20, 24]. The use of self-report instruments or self-report bingeing in some studies could have led to underestimations of BED [25]. In addition, the use of different versions of the Young Schema Questionnaire (YSQ) (short- versus long-form) with different numbers of EMS (14, 15, 16, 18 or 19) and models with different numbers of factors [17, 19, 20, 23, 26, 27], as well as more attention being given to EMS rather than domains, has contributed to the low consistency among findings [28].

On the basis of the above, this study had two aims: first, to explore EMS according to the four-factor model in obese subjects with BED versus a matched control group of obese patients; and second, to study the plausible predictive value of schema domains, together with eating and general psychopathologies, on BED diagnosis.

Materials and methods

Participants

All obese patients seeking weight loss treatment at the Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences of the University ‘Magna Graecia’ in Catanzaro (Italy), from September 2017 to March 2018, were invited to participate. They were entered into the study according to the following eligibility criteria: body mass index (BMI) > 29.9 kg/m2; age between 18 and 60 years; and having the ability to give valid consent and answer self-report questionnaires. Having a disease affecting the nervous system, major psychiatric disorders, taking drugs that could alter the ability to complete psychometric assessment or that could influence eating habits and being unable to give valid consent were considered exclusion criteria. All participants were given information about the aim of the study, the voluntary nature of participation and the management and storage of data; and all gave their written informed consent before any further steps were taken. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles set out in the Helsinki Declaration. The research protocol was authorised by the local Ethical Committee.

Measures

A trained psychiatrist interviewed participants and performed the structured clinical interview for the DSM-5 (SCID-5) [29] to assess patients for psychiatric disorders and conduct the eating-disorder examination (EDE 17.0D) [30]. Participants also underwent a nutritional and anthropometric evaluation (controlling for light clothing); standing height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and body weight to the nearest 0.1 kg at 8.00 a.m. Height and weight were measured using a portable stadiometer (Seca 220, GmbH & Co., Hamburg, Germany) and a balance scale (Seca 761, GmbH & Co., Hamburg, Germany), respectively, allowing BMI (kg/m2) to be calculated. Each candidate individually completed the following scales and questionnaires:

-

The Binge Eating Scale (BES) [31] investigates the presence and severity of binge eating through 16 items. A total BES score of < 17, 17–27 and > 27 indicates, respectively, unlikely, possible and probable BED. In the present study, the threshold was set at 17. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89.

-

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [32] is a self-report tool for evaluating the severity of depressive symptoms. It is made up of 21 items with three or four statement options from which patients choose the one that best fits their perception. Scores of < 10, 10–16, 17–29 and > 30 indicate, respectively, minimum, mild, moderate and severe depression. A total score > 16 was considered the clinical cut-off. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

-

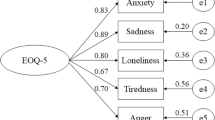

The Young Schema Questionnaire—Short Form 3 (YSQ-S3) [33]— is a self-report inventory that consists of 90 items rated on a six-point scale (from ‘completely untrue of me’ to ‘describes me perfectly’). According to Bach et al.’s [14] newly proposed model, the 90 items of YSQ-S3 are grouped into 18 EMSs clustered around four domains: (1) Disconnection and Rejection: emotional deprivation, social isolation, emotional inhibition, defectiveness, mistrust/abused, pessimism; (2) Impaired Autonomy and Performance: dependence, failure, subjugation, abandonment, enmeshment, vulnerability to harm; (3) Excessive Responsibility and Standards: self-sacrifice, unrelenting standards, self-punitiveness; (4) Impaired Limits: entitlement, approval/admiration seeking, insufficient self-control. In our study, alpha coefficients ranged from α = 0.740 (Excessive Responsibility and Standards) to α = 0.865 (Impaired Autonomy and Performance).

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics included frequencies and percentages, and means and standard deviations for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Differences between groups were explored through Chi-squared and t test as appropriate.

Logistic regression analysis was run to assess the extent to which significant variables and schema domains were independently associated with BED. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

According to their diagnosis, participants were assigned to group 1 (obese patients, N = 36) or group 2 (BED-obese patients, N = 34). Table 1 summarises the socio-demographic characteristics of the groups. The groups were similar on age, BMI, civil or marital status, employment and education; there were significantly fewer men in group 2.

Table 2 shows the comparisons between the groups on EDE, BES, BDI and YSQ scores. Group 2 has higher mean values for eating and weight concerns as measured by the EDE. The BED-obese patients also have higher average scores for BES, BDI and all four schema domains.

The results of logistic regression (− 2 Loglikelihood = 31.933; R2 Nagelkerke = 0.692) (Table 3) reveal that ‘Impaired Autonomy and Performance’ (YSQ) and ‘eating concern’ (EDE 17.OD) are independently associated with a BED diagnosis. Depression does not enter in the regression model, supporting a lack of association with BED diagnosis.

Discussion

This research sets out to explore the schema domains according to Young’s recent four-factor model in obese patients with and without BED and to ascertain whether these schema domains, together with eating and general psychopathologies, might plausibly be associated with a BED diagnosis in an obese sample. The results showed all four schema domains to display significantly more severe values in the BED-obese group. However, only the ‘Impaired Autonomy and Performance’ domain was shown to be independently associated with a BED diagnosis, suggesting that it may be crucial in the development and maintenance of the disorder.

In previous studies, several EMS belonging to various domains have been found to be associated with bingeing [17, 18] (i.e., the social isolation EMS loading with the Disconnection and Rejection domain; the abandonment EMS loading with the Impaired Autonomy and Performance domain; the enmeshment EMS loading with the Excessive Responsibilities and Standards domain; and the entitlement EMS loading with the Impaired Limits domain). Hence, it plausibly explains why all four domains may result in more severe values in BED group.

Another study [19] using a different four-factor model [34] found unhealthier domains in a BED sample than in a healthy control sample. More recently, others investigating schema domains in overweight and obese subjects in relation to food addiction and bingeing [35] have found binge eating severity to be associated with ‘Disconnection and Rejection’, ‘Impaired Limits’ and ‘Other-Directedness’ domains, but not with Impaired Autonomy and Performance. It is worth mentioning that these authors did not conduct a clinical assessment of BED and that the mean BES scores were much lower than those found in our study; moreover, the analysis was carried out on a single sample demonstrating both food addiction and binge eating, and having considerable comorbidity with other addiction disorders.

In our data, eating and weight concerns characterised the BED-obese patients: thinking and worrying about what, when and how to eat and its impact on body weight certainly impaired the everyday functioning of these patients. In fact, ‘eating concerns’ turned out to be independently associated with this diagnosis.

Our study confirms the pathological values of depression for obese patients with BED [4, 36, 37]. However, the question of whether depression precedes, is comorbid with or is a consequence of BED remains unresolved, because most studies have had cross-sectional design. EMS appears to be vulnerability factors for depression, both in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [38,39,40,41], but studies also support a strong association between dysfunctional schemas and both BED and depression [22]. Comparing the EMS exhibited by patients with either major depression, bulimia or bulimia and major depression, Waller and colleagues inferred that whilst the patients with major depression and bulimic depressed patients showed broadly similar EMS (social isolation and defectiveness/shame), they could still be differentiated in terms of their expression of certain core beliefs, above all ‘failure to achieve’ [16]. In the present study, depression was significantly more common among the BED patients, but did not prove to be independently associated with a BED diagnosis, as Impaired Autonomy and Performance did. Leung et al. found that differences in EMS between dieters testing positive or not for EDs were not influenced by actual depression [42], supporting the hypothesis that depression is an ‘insufficient causal factor’ for EDs and that EMS are needed [15]; nevertheless, future research should consider longitudinally whether the correlation between schemas and ED pathology persists after the resolution of depressive symptoms.

The small sample size, in accordance with our naturalistic design, and the absence of a normal weight healthy control group—obese subjects without BED were considered the ‘healthy controls’ for our BED subjects—are limitations of our study. Nevertheless, the main strength is the accuracy of BED diagnosis, performed using both clinical interview and standardised assessment instruments in accordance with DSM-5 criteria. With respect to the aforementioned methodological bias of YSQ, the present protocol made use of the short-form because of its greater convenience and comparable psychometric properties [16] and of the four-factor model, which is empirically and conceptually more consistent either with Young’s schema therapy or need-thwarting parenting experienced in childhood [14]. The inclusion of an age- and weight-matched control group of obese patients is another strength corroborating previous studies supporting different phenotypes for obese patients with and without BED [4].

In conclusion, ‘Impaired Autonomy and Performance’ was associated with a BED diagnosis in obese patients. The evaluation of EMS in young adults or adults that already meet the diagnosis of BED found its rationale in some evidences suggesting that improvement in autonomy (reduced sensitivity to others and greater capacity to manage new situations) is associated with recovery in ED patients [43]. Lastly, as schema domains develop in childhood before BED takes place, they could be evaluated as early risk factors for EDs in primary prevention campaigns targeting young overweight and obese children.

Clinical implications and further research

The persistence or recrudescence of eating psychopathology after conventional psychotherapy (i.e., CBT) can be understood in terms of a deeper disturbance in schema cognition and other longitudinal and enduring factors, such as personality, depression and emotional dysregulation, not addressed by CBT [10, 44]. According to the schema-focused model of EDs, eating behaviours are thought to operate as coping strategies, preventing or alleviating emotions activated by schemas in the absence of alternative and more appropriate coping strategies; accordingly, the need for psychotherapy that addresses more specific domains other than eating disorders appears as a reasonable one [11].

The rationale for ST is rooted in its effectiveness in treating enduring cognition disorders and personality disorders [1], depression [16] and emotion dysregulation [45], which often are comorbid with eating psychopathology.

Few studies have explored ST efficacy in BED [15]. To date, there is more robust evidence for CBT; ST could be considered an augmentation strategy in circumstances in which CBT fails and when eating disorders are comorbid with affective and personality disorders [10].

To our knowledge, only one randomised controlled trial (RCT) study has compared the effectiveness of conventional CBT versus ST; it found no significant differences either at baseline or after 12 months in bingeing frequency, abstinence and remission rates, weight loss or EDE psychopathology. The authors argued that the study’s power was such that it was unlikely to detect group differences; moreover, other limitations were hypothesised to account for the results, such as limited generalisability for ethnicity and unusual length of time of therapies [11]. Further, randomised controlled trials with longer follow-up are needed to establish the extent to which ST could be more effective than conventional CBT, alone or in combination, in the long term.

References

Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC (2007) The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry 61:348–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

Stice E, Marti CN, Rohde P (2013) Prevalence, incidence, impairment, and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young women. J Abnorm Psychol 122:445–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030679

Palavras MA, Kaio GH, de Mari J, Claudino AM (2011) A review of Latin American studies on binge eating disorder. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 33(Suppl 1):S81–S108

Caroleo M, Primerano A, Rania M et al (2018) A real world study on the genetic, cognitive and psychopathological differences of obese patients clustered according to eating behaviours. Eur Psychiatry 48:58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.11.009

Segura-Garcia C, Caroleo M, Rania M et al (2017) Binge eating disorder and bipolar spectrum disorders in obesity: psychopathological and eating behaviors differences according to comorbidities. J Affect Disord 208:424–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.005

Succurro E, Segura-Garcia C, Ruffo M et al (2015) Obese patients with a binge eating disorder have an unfavorable metabolic and inflammatory profile. Medicine (Baltimore) 94:e2098. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002098

John M (2007) Eisenberg center for clinical decisions and communications science. Management and outcomes of binge-eating disorder in adults: current state of the evidence, 24 May 2016. In: Comparative effectiveness review summary guides for clinicians. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK368366/

Smink FRE, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW (2013) Epidemiology, course, and outcome of eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 26:543–548. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e328365a24f

Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Peat CM, Lohr KN, Cullen KE, Morgan LC, Bann CM, Wallace IF, Bulik CM (2015) Management and outcomes of binge-eating disorder. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK338312/

Waller G, Kennerley H, Ohanian V (2007) Schema-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders. Cognitive schemas and core beliefs in psychological problems: a scientist-practitioner guide. American Psychological Association, Washington, pp 139–175

McIntosh VVW, Jordan J, Carter JD et al (2016) Psychotherapy for transdiagnostic binge eating: a randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy, appetite-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy, and schema therapy. Psychiatry Res 240:412–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.080

Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar ME (2003) Schema therapy : a practitioner’s guide. Guilford Press, New York

Young JE (1994) Cognitive therapy for personality disorders: a schema-focused approach, Rev. Professional Resource Press/Professional Resource Exchange, Sarasota

Bach B, Lockwood G, Young JE (2018) A new look at the schema therapy model: organization and role of early maladaptive schemas. Cogn Behav Ther 47:328–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2017.1410566

Pugh M (2015) A narrative review of schemas and schema therapy outcomes in the eating disorders. Clin Psychol Rev 39:30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.04.003

Waller G, Shah R, Ohanian V, Elliott P (2001) Core beliefs in bulimia nervosa and depression: the discriminant validity of young’s Schema Questionnaire. Behav Ther. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7894(01)80049-6

Waller G, Ohanian V, Meyer C, Osman S (2000) Cognitive content among bulimic women: the role of core beliefs. Int J Eat Disord 28:235–241

Waller G (2003) Schema-level cognitions in patients with binge eating disorder: a case control study. Int J Eat Disord 33:458–464. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10161

Dingemans AE, Spinhoven P, van Furth EF (2006) Maladaptive core beliefs and eating disorder symptoms. Eat Behav 7:258–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.09.007

Waller G, Dickson C, Ohanian V (2002) Cognitive content in bulimic disorders: core beliefs and eating attitudes. Eat Behav 3:171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1471-0153(01)00056-3

Leung N, Waller G, Thomas G (1999) Core beliefs in anorexic and bulimic women. J Nerv Ment Dis 187:736–741

Van Vlierberghe L, Braet C, Goossens L (2009) Dysfunctional schemas and eating pathology in overweight youth: a case-control study. Int J Eat Disord 42:437–442. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20638

Zhu H, Luo X, Cai T et al (2016) Life event stress and binge eating among adolescents: the roles of early maladaptive schemas and impulsivity. Stress Health 32:395–401. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2634

Leung N, Waller G, Thomas G (2000) Outcome of group cognitive-behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa: the role of core beliefs. Behav Res Ther 38:145–156

Brennan KA, Shaver PR (1995) Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 21:267–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295213008

Unoka Z, Tölgyes T, Czobor P, Simon L (2010) Eating disorder behavior and early maladaptive schemas in subgroups of eating disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis 198:425–431. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e07d3d

Lawson R, Emanuelli F, Sines J, Waller G (2008) Emotional awareness and core beliefs among women with eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 16:155–159. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.848

Jones C, Harris G, Leung N (2005) Core beliefs and eating disorder recovery. Eur Eat Disord Rev 13:237–244. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.642

First MB (2016) SCID-5-CV : structured clinical interview for DSM-5 disorders, clinician version. American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Calugi S, Ricca V, Castellini G et al (2015) The eating disorder examination: reliability and validity of the Italian version. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorexia Bulim Obes 20:505–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0191-2

Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, Rardin D (1982) The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict Behav 7:47–55

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M et al (1961) An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 4:561–571

Young JE (2005) Young Schema Questionnaire—short form 3 (YSQ-S3). Cognitive Therapy Center, New York, NY

Lee CW, Taylor G, Dunn J (1999) Factor structure of the Schema Questionnaire in a large clinical sample. Cognit Ther Res 23:441–451. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018712202933

Imperatori C, Innamorati M, Lester D et al (2017) The association between food addiction and early maladaptive schemas in overweight and obese women: a preliminary investigation. Nutrients 9:1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9111259

Bóna E, Szél Z, Kiss D, Gyarmathy VA (2018) An unhealthy health behavior: analysis of orthorexic tendencies among Hungarian gym attendees. Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0592-0

Nicholls W, Devonport TJ, Blake M (2016) The association between emotions and eating behaviour in an obese population with binge eating disorder. Obes Rev 17:30–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12329

Riso LP, du Toit PL, Blandino JA et al (2003) Cognitive aspects of chronic depression. J Abnorm Psychol 112:72–80

Riso LP, Froman SE, Raouf M et al (2006) The long-term stability of early maladaptive schemas. Cognit Ther Res 30:515–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9015-z

Halvorsen M, Wang CE, Eisemann M, Waterloo K (2010) Dysfunctional attitudes and early maladaptive schemas as predictors of depression: a 9-Year follow-up study. Cognit Ther Res 34:368–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-009-9259-5

Hoffart A, Sexton H, Hedley LM et al (2005) The structure of maladaptive schemas: a confirmatory factor analysis and a psychometric evaluation of factor-derived scales. Cognit Ther Res 29:627–644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-005-9630-0

Leung N, Price E (2007) Core beliefs in dieters and eating disordered women. Eat Behav 8:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.01.001

Kuipers GS, Hollander S, van der Ark LA, Bekker MHJ (2017) Recovery from eating disorder 1 year after start of treatment is related to better mentalization and strong reduction of sensitivity to others. Eat Weight Disord 22(3):535–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0405-x

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R (2003) Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther 41:509–528

Simpson CC, Mazzeo SE (2017) Attitudes toward orthorexia nervosa relative to DSM—5 eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 50:781–792. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22710

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all partakers for the time they spent for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Approval from the Ethical Committee of University Hospital Mater Domini at Catanzaro was obtained before data were collected for the current study.

Informed consent

Patients gave their informed consent before any research procedure took place.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rania, M., Aloi, M., Caroleo, M. et al. ‘Impaired Autonomy and Performance’ predicts binge eating disorder among obese patients. Eat Weight Disord 25, 1183–1189 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00747-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00747-z