Abstract

Purpose

Parental invalidation and narcissism have been proposed to play an important role in understanding the etiology of eating disorders. The current research aimed to address two main gaps in the literature. The first aim was to determine the differential associations of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism with eating disorder pathology. The second aim was to find a common mediator between both maternal and paternal invalidation and eating disorder pathology. It was hypothesized that when controlling for vulnerable narcissism, grandiose narcissism would not predict eating disorder pathology. In addition, it was hypothesized that vulnerable narcissism would be a mediator of the relationship between parental invalidation and eating disorder pathology.

Methods

Participants were 352 women aged 18–30 years who were recruited from the general and tertiary student population, and as such constituted a community sample. Participants completed the Invalidating Childhood Environment Scale, Brief-Pathological Narcissism Inventory, Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire, the Avoidance of Affect Subscale of the Distress Tolerance Scale, and the Emotional Expression as a Sign of Weakness Subscale of the Attitudes Towards Emotional Expression Scale in an online survey.

Results

Results showed that, when controlling for vulnerable narcissism, grandiose narcissism was no longer associated with eating disorder pathology. It was also found that parental invalidation had a positive indirect effect upon eating disorder pathology, via vulnerable narcissism.

Conclusions

The findings indicate that vulnerable narcissism is more strongly associated with eating disorder pathology as opposed to grandiose narcissism and help to further elucidate the mechanisms via which parental invalidation might exert its negative effect on eating disorder pathology.

Level of evidence

A cross-sectional survey (Level V).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Eating disorders are complex, often difficult to treat, and poorly understood. Research, however, has demonstrated a range of personality traits that are associated with eating disorder pathology [1] among which is narcissism [2]. Pathological narcissism consists of two subtypes, grandiose and vulnerable narcissism [3]. Grandiose narcissism refers to a collection of behaviors and cognitions such as repressing negative aspects of the self and distorting disconfirming external information resulting in an inflated sense of self, feelings of entitlement and superiority, demanding of attention from others, and low empathy [3]. Vulnerable narcissism, on the other hand, is characterized by the conscious experience of helplessness, emptiness, low self-esteem, and shame. It is also characterized by social avoidance in situations where the ideal self cannot be presented, or in situations where the need for admiration will not be met [3].

Supporting the relevance of narcissism for eating disorders, Zerach [2] found that both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism were associated with eating disorder pathology. The study found that vulnerable and grandiose narcissism were both significantly associated with dieting and oral control behaviors and attitudes, but only vulnerable narcissism was associated with bulimic behaviors. Similarly, a study [4] showed that individuals with eating disorders scored significantly higher on both vulnerable and grandiose narcissism compared to the healthy controls, but there was only a significant difference in vulnerable narcissism scores between individuals with eating disorders and those with an anxiety disorder. These studies were cross-sectional and are, therefore, unable to fully establish a causal link.

Offering stronger support for causal link, longitudinal research has shown that grandiose and vulnerable narcissism have different predictive relationships with future dieting behaviors and future bulimic behaviors [5]. This study found that vulnerable narcissism predicted dieting behaviors, whereas grandiose narcissism predicted future bulimic behaviors. These findings are in contrast to a study, showing that vulnerable narcissism (and not grandiose narcissism) predicted the eating disorder behaviors characterizing anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, a finding that may be due to the fact that this was the only study to control for vulnerable narcissism when examining the relationship between grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism and eating disorder pathology [6].

The association between narcissism and eating disorder symptoms may be explained by a common developmental factor: childhood invalidation. An invalidating childhood environment is defined as one in which the parents either ignore or respond negatively to the child’s communication, leading to poor distress tolerance in children [6]. Research indicates that parental invalidation is a predictor of narcissism and eating disorder pathology. For example, one study found that participants with eating disorders reported significantly higher levels of perceived parental invalidation during childhood compared to a non-clinical sample [7]. The study also found avoidance of affect to be a partial mediator between perceived paternal (but not maternal) invalidation during childhood and eating disorder symptoms. Another study found that although individuals with bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa perceived similar levels of maternal invalidation; those with bulimia nervosa reported higher perceived paternal invalidation than those with anorexia nervosa [8]. Expanding on these findings, a study in a non-clinical sample found that an invalidating childhood environment was associated with all adult eating disorder behaviors and cognitions [9]. This study also found that the attitude that expressing emotions is a sign of weakness was a full mediator of the relationship between maternal (but not paternal) invalidation and eating concern. Research is yet to find a common mediator of both maternal and paternal invalidation. As such, the current study aims to explore a potential common mediator of the two, which would imply a shared developmental process.

Given the aforementioned link between narcissism and eating disorder symptoms, it is possible that narcissism acts as a mediator in the association between parental invalidation and eating disorders. Although theoretically posited [10], a relationship between invalidation and the two types of narcissism has only been recently empirically tested [11]. The results indicated that paternal and maternal invalidation during childhood were significant predictors of both vulnerable and grandiose narcissism. In addition, these researchers propose that parental invalidation might act as a common predisposing factor for a range of mental health issues associated with the self-regulation, which often co-occur, such as narcissism and eating disorders [11]. More specifically, it is proposed that parental invalidation results in a poor sense of internal regulation of the self, with regulation instead sought by garnering approval and validation from others. Theorists posit that the development of a sense of self and its regulation are based on interpersonal interactions, especially with caregivers. In an invalidating environment, the child’s needs for regulation of the self, such as praise or validation, are not met or are minimized. As such, the child is unable to learn how to regulate their own sense of self and associated affect [10, 12].

Theoretical and empirical work suggests that vulnerable narcissism will be a stronger predictor of eating disorder symptoms than grandiose narcissism, and would have a stronger potential at being a mediator of the relationship between parental invalidation and eating disorder pathology. Individuals high in narcissism require external validation to maintain their sense of self, but, in vulnerable narcissism due to their non-assertive and avoidant interpersonal style, they are often unable to do this [3, 13, 14]. Based on the interpersonal model of eating disorders [15], the experiences of low interpersonal validation that are part of vulnerable narcissism are theorized to trigger negative self-worth and associated affect, which in turn trigger eating disorder symptoms. In contrast, grandiose narcissism is characterized by an assertive interpersonal style and the ability to distort disconfirming information to maintain an inflated sense of self. Thus, individuals high in grandiose narcissism, even if by distortion, are more able to more effectively use external means for regulating their sense of self and associated affect [3, 13, 16].

In summary, research to date suggests the associations between parental invalidation, narcissism, and eating disorder pathology, but only one study [6] has controlled for vulnerable narcissism when exploring the relationship between grandiose narcissism and eating disorder pathology, and there have been no studies testing whether narcissism might mediate the observed association between parental invalidation and eating disorder pathology. Thus, there are two main aims of the current study. First, the study seeks to investigate the differential predictive capabilities of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism for eating disorder pathology. Second, the study aims to determine if vulnerable narcissism could act as a mediator between both maternal and paternal invalidation and eating disorder pathology. It is hypothesized that vulnerable narcissism will have a significant positive association with eating disorder pathology (H1a), and that, when controlling for vulnerable narcissism, there will be no significant association between grandiose narcissism and eating disorder pathology (H1b). It is further hypothesized that maternal invalidation will have a significant positive indirect effect on eating disorder pathology via vulnerable narcissism, even when controlling for the belief that expression of emotions is a sign of weakness (H2a); and that paternal invalidation will have a significant positive indirect effect on eating disorder pathology via vulnerable narcissism, even when controlling for avoidance of affect (H2b). Emotional expression as a sign of weakness and avoidance of affect are included as they were shown to be mediators between maternal invalidation and eating disorder pathology [7], and paternal invalidation and eating disorder pathology [9], respectively.

Methods

Participants

A community sample of 394 female participants was recruited using online platforms such as Facebook and Reddit, and through a research participation scheme at an Australian university. Participants over the age of 30 were excluded, resulting in a total sample of 352 participants. Only females were recruited for this study given the higher prevalence of eating disorders among girls and women [17]. The mean age was 20.6 years (SD 2.8), with an age range of 18–30 years. The sample consisted of 64.8% white females. The proportion of university students was 59.7%.Footnote 1 The majority of participants (92%) were raised by both their biological mother and father. There was no difference in the pattern of significant findings in analyses with and without the participants who were not raised by their biological mother and father. Hence, all participants were retained for the final analyses.

Procedure and measures

Participants completed an online survey that consisted of the following measures.

Invalidating Childhood Environment Scale (ICES)

This measure of perceived parental invalidation includes items that reflect the eight themes used to define an invalidating environment, that is, when parents are perceived to “ignore thoughts and judgments; ignore emotions; negate thoughts and judgments; negate emotions; over-react to emotions; overestimate problem solving; over-react to thoughts and judgments; and oversimplify problems” [7]. Only the first part of the ICES that captures parental invalidation was used, as the second part capturing family styles was not relevant for the research question. Paternal and maternal invalidation was measured with 14 items using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (all the time), and these items were scored for the mother and father separately (with four reverse scored). The measures of both maternal invalidation (α = 0.92) and paternal invalidation (α = 0.92) were reliable in the present study.

Brief-Pathological Narcissism Inventory (B-PNI)

The B-PNI [18] was used to measure grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. This scale has 28 items that use a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me). The items for each type of narcissism were averaged, with higher scores indicating higher levels of narcissism. The measures of grandiose (α = 0.82) and vulnerable (α = 0.91) narcissism were reliable in the present study.

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q)

The EDE-Q measured eating disorder pathology over the past 28 days [19]. It consists of 22 items yielding four subscales (i.e., restraint, eating concern, shape concern, and weight concern), with items measured on a seven-point Likert-type scale referring to either frequency ranging from 1 (no days) to 7 (every day) or intensity ranging from 0 (not at all) to 6 (markedly). Item scores were summated and averaged to obtain a mean total score of eating disorder pathology, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. In the present study the EDE-Q total score was reliable (α = 0.97).

Avoidance of Affect Subscale

This subscale of the Distress Tolerance Scale [7] was used to measure the avoidance of affect coping style. It consists of six items rated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). These scores are averaged to obtain a subscale score, with higher scores indicating higher level of avoidance of affect. This subscale was reliable (α = 0.71) in the present study.

Attitude Towards Emotional Expression as a Sign of Weakness Subscale

This is a subscale of the Attitudes Towards Emotional Expression Scale [20], which measures the extent to which an individual believes that expressing emotions is a sign of weakness. The subscale consists of five items rated on a seven-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and was reliable (α = 0.90) in the present study. The average across the five items was obtained, with higher scores indicating stronger attitudes that expressing emotions is a weakness.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 22 was used for statistical analyses. All hypotheses were tested at p < 0.05 significance levels. The PROCESS macro was used to conduct mediation analyses [21], which runs 5000 bias-corrected re-samples to obtain a 95% confidence interval around the indirect effect.

Results

Descriptive statistics

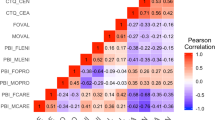

Table 1 provides the means, standard deviations, and range of the study variables. In the current sample all variables spanned almost the full range.

Sequential regression analyses

Sequential regression analyses were conducted to test hypotheses 1a and 1b. A tolerance value of 0.70 indicated no problems with multicollinearity [22]. In step 1, grandiose narcissism was included as the explanatory variable with eating disorder pathology (EDE-Q total scores) as the outcome variable; in step 2, vulnerable narcissism was added. As seen in Table 2, grandiose narcissism predicted EDE-Q total scores, but, in step 2 with the addition of vulnerable narcissism, grandiose narcissism became a non-significant predictor. Vulnerable narcissism predicted an additional 12% of the variance in EDE-Q total scores (ΔR2 = 0.12, p < 0.01). These results indicate that vulnerable narcissism is more strongly associated with eating disorder pathology (H1a), and that, when controlling for it, grandiose narcissism is no longer associated with eating disorder pathology (H1b).

Mediation analyses

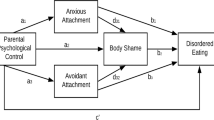

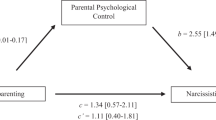

H2a states that perceived maternal invalidation during childhood would have a significant indirect effect upon EDE-Q total scores via vulnerable narcissism, even when controlling for the belief that expression of emotions is a sign of weakness. A mediation model was tested using PROCESS with maternal invalidation as the explanatory variable, EDE-Q total scores as the outcome variable, and vulnerable narcissism and the belief that emotional expression is a sign of weakness as the mediators.

Figure 1 shows that the association of maternal invalidation with EDE-Q total scores decreased once vulnerable narcissism and emotional expression as a sign of weakness were entered as mediators. The association of vulnerable narcissism with EDE-Q total scores remained significant, whereas the association of emotional expression as a sign of weakness did not. This showed that vulnerable narcissism mediated the effect of maternal invalidation on EDE-Q total scores, but emotional expression as a sign of weakness did not. The indirect effect of vulnerable narcissism was 0.29 (the standardized effect was 0.15), and the 95% confidence interval did not contain zero (0.18, 0.42; standardized: 0.09, 0.22), suggesting that the effect was significant. On the other hand, the indirect effect of emotional expression as a sign of weakness was 0.05 (standardized = 0.02), but the 95% confidence interval contained zero (− 0.06, 0.16; standardized: − 0.03, 0.08), meaning that this weak effect was not significant. This supported H2a.

The mediation model of maternal invalidation, vulnerable narcissism, emotional expression as a sign of weakness, and EDE-Q total scores. The unstandardized (B) and standardized (β) direct effects are shown. The first effect value between maternal invalidation and EDE-Q total score (the value before the forward slash) shows the total effect of maternal invalidation on EDE-Q total score, and the second effect value (the value after the forward slash) shows the direct effect of maternal invalidation on EDE-Q total score, controlling for mediators. ***p < 0.001

H2b stated that perceived paternal invalidation during childhood would have a significant indirect effect upon EDE-Q total scores via vulnerable narcissism, even when controlling for avoidance of affect. A mediation model was analyzed using PROCESS with paternal invalidation as the explanatory variable, EDE-Q total scores as the outcome variable, and vulnerable narcissism and avoidance of affect as the mediators.

Figure 2 shows that the association of paternal invalidation with EDE-Q total scores decreased once vulnerable narcissism and avoidance of affect were entered as mediators. The association of vulnerable narcissism with EDE-Q total scores remained significant, whereas the association of avoidance of affect did not. This indicated that vulnerable narcissism mediated the effects of paternal invalidation on EDE-Q total scores, but avoidance of affect did not. The indirect effect of vulnerable narcissism was 0.25 (standardized = 0.13), and the 95% confidence interval did not contain zero (0.16, 0.35; standardized: 0.08, 0.19), suggesting that the effect was significant. The indirect effect of avoidance of affect was 0.01 (standardized = 0.01), but the 95% confidence interval contained zero (− 0.06, 0.10; standardized: − 0.04, 0.05), suggesting that the effect was not significant. This supported H2b.

The mediation model of paternal invalidation, vulnerable narcissism, avoidance of affect, and EDE-Q total scores. The unstandardized (B) and standardized (β) direct and indirect effects are shown. The first effect value between paternal invalidation and EDE-Q total score (the value before the forward slash) shows the total effect of paternal invalidation on EDE-Q total score, and the second effect value (the value after the forward slash) shows the direct effect of paternal invalidation on EDE-Q total score, controlling for mediators. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Discussion

The current study sought to address two main gaps in the literature. First, the study sought to further elucidate the differential associations of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism with eating disorder pathology. The current findings support the role of vulnerable over grandiose narcissism in the prediction of eating disorder symptoms. Second, within the literature, there is potential for a more comprehensive mediator for the relationship between parental invalidation and eating disorder pathology, namely, vulnerable narcissism. The current study found that vulnerable narcissism accounted for the indirect associations of both maternal and paternal invalidation with eating disorder symptoms, whereas the other potential mediators did not.

In relation to the first aim, the finding that grandiose narcissism was no longer associated with eating disorder pathology after accounting for vulnerable narcissism suggests that the previous research findings showing an association between grandiose narcissism and eating disorder symptoms [2, 4, 5] are likely due to its shared characteristics with vulnerable narcissism. Both forms of narcissism are strongly correlated as evidenced in both the current (r = 0.57, p < 0.05) and previous studies, and share features such as possessing a sense of entitlement and requiring external validation to maintain a sense of self [16]. The present finding that the unique characteristics of grandiose narcissism (e.g., distorting external information to maintain an inflated sense of self, a sense of superiority, and a lack of empathy) were unable to predict eating disorder pathology over and above vulnerable narcissism suggests that it is primarily vulnerable narcissism that is associated with eating disorder pathology. This finding is consistent with the previous research, showing that vulnerable narcissism is characterized by a sense of self contingent upon external feedback along with an avoidant interpersonal style that is unable to garner this validation [3, 16]. The negative interpersonal interactions may then result in a negative sense of self and associated negative affect, which are theorized to, in turn, trigger eating disorder behaviors among individuals such as the pursuit of thinness to enhance self-esteem or engagement in binge eating episodes to regulate negative affect [15]. In contrast, negative self-worth and affect induced by negative social interactions would not be expected in individuals high on grandiose narcissism as they are able to skew negative social feedback to maintain a positive self-image and have an assertive interpersonal style [3, 13].

The present study also sought to investigate a mediational model that would account for both paternal and maternal invalidation in the prediction of eating disorder pathology via vulnerable narcissism. Parental invalidation during childhood has been shown to be related to self-dysregulation [23,24,25], which is evident in narcissism. Self-dysregulation, in turn, results in a reliance on external sources of validation to maintain a positive sense of self. For those with vulnerable narcissism, who do not engage in the positive distortion of interpersonal feedback characteristic of those with grandiose narcissism, negative social feedback could then increase the likelihood of engaging in maladaptive eating behaviors to maintain the sense of self and positive affect.

Past research has found that distinct constructs mediate the relationship between maternal invalidation and eating disorder symptoms, that is, the attitude that expressing emotions is a sign of weakness [9], and between paternal invalidation and eating disorder symptoms, that is, avoidance of affect [7]. In contrast, the current study was able to find a common mediator (i.e., vulnerable narcissism) for both maternal and paternal invalidation and eating disorder symptoms. Moreover, it was found that maternal and paternal invalidation had a significant indirect effect via vulnerable narcissism on eating disorder symptoms, but not via avoidance of affect and the attitude that emotional expression is a sign of weakness. Though related to vulnerable narcissism, neither avoidance of affect nor the attitude that emotional expression is a sign of weakness encompass the core characteristics of vulnerable narcissism, that is, a need for external validation to maintain a positive sense of self, and an associated interpersonal style that is unable to do so. The present data would suggest that vulnerable narcissism has the potential to provide a stronger and more parsimonious account of the mechanism underlying the relationship between parental invalidation and eating disorder symptoms than previously explored constructs (i.e., avoidance of affect and emotional expression as a sign of weakness).

The current findings should be considered in light of several limitations. Among these are those features that make it difficult to establish causality. The cross-sectional design of the study and the retrospective nature of the ICES and the liability of recall bias mean that it is not possible to determine if the perception of invalidation and vulnerable narcissism preceded the development of eating disorder symptoms. The study also did not control for developmental differences such as culture and trauma which could also impact the results. Moreover, the study used a community sample, such that replication in clinical samples is warranted. In addition, the sample consisted solely of female participants, such that replication using male participants is needed. It would be important to study these processes in a non-Western sample as there are reported differences in narcissism across cultures [26]. Finally, given the differing operationalizations of narcissism, it is important to test these relationships utilizing different conceptualizations of narcissism such as the mask model of narcissism [27].

In summary, this study found that grandiose narcissism was not associated with eating disorder pathology when controlling for vulnerable narcissism and that vulnerable narcissism acts a common mediator between parental invalidation (both maternal and paternal) and eating disorder pathology. The study reiterates the potential importance of vulnerable narcissism in the etiology of eating disorders and provides the initial evidence for the potential of vulnerable narcissism to account for the mechanism through which parental invalidation may impact eating disorder pathology. Future research, specifically longitudinal data, is necessary to understand the temporal nature of this relationship. Furthermore, since past research has shown that narcissism is associated with a range of difficulties in engaging in treatment [28], including in eating disorder treatment settings [29], understanding the link between narcissism and eating disorder pathology (and the developmental framework that may underpin this association) may be beneficial in treatment planning.

Notes

The full break down of the ethnicities and country of origin of the participants are included in Appendix A of the supplemental materials.

References

Stice E (2002) Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 128:825–848. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.128.5.825

Zerach G (2014) The associations between pathological narcissism, alexithymia and disordered eating attitudes among participants of pro-anorexic online communities. Eat Weight Disord 19:337–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-013-0096-x

Pincus AL et al (2009) Initial construction and validation of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. Psychol Assess 21:365. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016530

Boucher K et al (2015) The relationship between multidimensional narcissism, explicit and implicit self-esteem in eating disorders. Psychology 6:2025. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2015.615200

Dakanalis A, Clerici M, Carrà G (2016) Narcissistic vulnerability and grandiosity as mediators between insecure attachment and future eating disordered behaviors: a prospective analysis of over 2,000 freshmen. J Clin Psychol 72:279–292 https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22237

Gordon KH, Dombeck JJ (2010) The associations between two facets of narcissism and eating disorder symptoms. Eat Behav 11:288–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.08.004

Mountford V et al (2007) Development of a measure to assess invalidating childhood environments in the eating disorders. Eat Behav 8:48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.01.003

Haslam M et al (2008) Invalidating childhood environments in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Eat Behav 9:313–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.10.005

Haslam M et al (2012) Attitudes towards emotional expression mediate the relationship between childhood invalidation and adult eating concern. Eur Eat Disord Rev 20:510–514. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2198

Linehan MM (1993) Cognitive behavioral therapy of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press, New York

Huxley E, Bizumic B (2017) Parental invalidation and the development of narcissism. J Psychol 151:130–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2016.1248807

Monell E et al (2015) Emotion dysregulation, self-image and eating disorder symptoms in University Women. J Eat Disord 3:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-015-0083-x

Dickinson K, Pincus AL (2003) Interpersonal analysis of grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism. J Pers Disord 17:188–207. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.17.3.188.22146

Hartmann A, Zeeck A, Barrett MS (2010) Interpersonal problems in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 43:619–627. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20747

Rieger E et al (2010) An eating disorder-specific model of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT-ED): causal pathways and treatment implications. Clin Psychol Rev 30:400–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.001

Krizan Z, Herlache AD (2017) The narcissism spectrum model. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 22:3–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868316685018

Hudson JI et al (2007) The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry 61:348–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

Schoenleber M et al (2015) Development of a brief version of the pathological narcissism inventory. Psychol Assess 27:1520–1526. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000158

Fairburn CG, Beglin S (2008) Eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q 6.0). In: Fairburn CG (ed) Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders. Guildford Press, New York

Joseph S et al (1994) The preliminary development of a measure to assess attitudes towards emotional expression. Personal Individ Differ 16:869–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)90231-3

Hayes AF (2013) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression based approach. Guilford Press, New York

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2013) Using multivariate statistics, 6th edn. Pearson, London

Krause ED, Mendelson T, Lynch TR (2003) Childhood emotional invalidation and adult psychological distress: the mediating role of emotional inhibition. Child Abuse Negl 27:199–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00536-7

Robertson CD, Kimbrel NA, Nelson-Gray RO (2013) The Invalidating Childhood Environment Scale (ICES): psychometric properties and relationship to borderline personality symptomatology. J Personal Disord 27:402–410. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2012_26_062

Shenk CE, Fruzzetti AE (2013) Parental validating and invalidating responses and adolescent psychological functioning: an observational study. Fam J 22:43–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480713490900

Foster JD, Campbell WK, Twenge JM (2003) Individual differences in narcissism: inflated self-views across the lifespan and around the world. J Res Personal 37:469–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00026-6

O’Brien ML (1987) Examining the dimensionality of pathological narcissism: factor analysis and construct validity of the O’Brien multiphasic narcissism inventory. Psychol Rep 61:499–510. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1987.61.2.499

Pincus AL, Cain NM, Wright AGC (2014) Narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability in psychotherapy. Personal Disord Theory Res Treat 5:439–443. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000031

Campbell MA, Waller G, Pistrang N (2009) The Impact of narcissism on drop-out from cognitive-behavioral therapy for the eating disorders: a pilot study. J Nerv Ment Dis 197:278–281. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31819dc150

Funding

There has been no funding received in conducting the study and in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Australian National University (ANU) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethics approval was obtained from the ANU Human Research Ethics Committee prior to conducting this research.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Open Science Framework repository, https://mfr.osf.io/render?url=https://osf.io/6xpfg/?action=download%26mode=render.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Personality and eating and weight disorders.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sivanathan, D., Bizumic, B., Rieger, E. et al. Vulnerable narcissism as a mediator of the relationship between perceived parental invalidation and eating disorder pathology. Eat Weight Disord 24, 1071–1077 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00647-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00647-2