Abstract

Overparenting, or “helicopter parenting,” can be generally characterized as parenting that is well-intentioned, but over-involved and intrusive. This style of parenting has been especially highlighted in the lives of young adults, who may be inhibited by this form of parenting in the appropriate development of autonomy and independence. Overparenting shares conceptual similarities with parents’ psychological control practices, which involve emotional and psychological manipulation of children (e.g., inducing guilt, withholding love as a form of control). Although these constructs contain key differences, both have been linked to narcissism in young adults, by way of parental over-involvement in children’s lives. Thus, we sought to explore parental psychological control as a mediator between overparenting and narcissism, including in regard to both grandiose and vulnerable narcissistic phenotypes. Participants included 380 young adult college students (age range: 18–26 years) who completed the Pathological Narcissism Inventory, as well as reports of their parents’ behaviors related to overparenting and psychological control. Mediation analyses through Process in SPSS supported the hypothesized role of parental psychological control as a mediator between overparenting and narcissistic traits, including traits related to both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Effect sizes for each analysis were modest. This study further clarifies the nature of overparenting, and speaks to the need for further research in establishing the mechanisms by which overparenting may lead to narcissistic traits among young adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Overparenting, otherwise known as “helicopter parenting” by researchers and media, has recently been implicated in the development of narcissistic traits among young adult children (Segrin et al. 2012, 2013). However, the mechanisms responsible for the link between overparenting and narcissism are not well understood. Parental psychological control (PPC), which includes parenting practices focused on emotional intrusion (Barber 1996), may be one such link, as this construct has been tied to both overparenting and narcissistic features (Givertz and Segrin 2014; Padilla-Walker and Nelson 2012). Moreover, the role of PPC between overparenting and narcissism may vary across narcissistic phenotypes, as grandiose and vulnerable narcissism are thought to possess different etiologies (Horton et al. 2006; Kohut 1977).

Overparenting is a parenting style conceptualized as parental over-involvement and intrusiveness, coupled with high levels of parental warmth and responsiveness (Padilla-Walker and Nelson 2012; Segrin et al. 2013; Schiffrin et al. 2014). This style of parenting, which appears related to the advent of technology (e.g., cell phones, social networking) in parents’ ability to monitor their children’s whereabouts and behavior (LeMoyne and Buchanan 2011), has been lamented by popular media as contributing to what appears to be an escalation of dependency and functional decline in college students (Joyce 2014; Morrison 2015), as well as a rise in narcissistic traits among the current millennial generation (Asghar, 2014). Often described as hovering over their young adult children (Schiffrin et al. 2014), “helicopter parents” are often seen as micromanaging their young adult children’s personal and professional lives (LeMoyne and Buchanan 2011), with prototypical examples including parents contacting professors over grade disputes (e.g., Hyman and Jacobs 2010) or attending their child’s job interview (e.g., Begley 2013). In short, overparenting appears typified by parents who impede on appropriate development of young adult independence (Nelson 2010; Segrin et al. 2015).

Conceptually, overparenting is characterized by high levels of warmth and support, combined with high levels of parental control, and low levels of autonomy-granting (Segrin et al. 2013). Thus, while overparenting shares similarities with parenting styles such as authoritative parenting (i.e., high levels of warmth, moderate levels of control) and authoritarian parenting (i.e., low levels of warmth and autonomy-granting, high levels of control; Baumrind 1966, 1967), its unique combination of these factors (i.e., high warmth, high control, and low autonomy-granting) distinguish it from authoritative and authoritarian parenting (Padilla-Walker and Nelson 2012). In fact, overparenting has been compared to oversolicitous parenting observed in parents of younger children, where parents display high levels of warmth and involvement in situations where children do not need assistance or reassurance (Rubin et al. 1997). Oversolicitous parenting has been linked to detrimental outcomes among preschool children, including greater symptoms of depression and anxiety (Bayer et al. 2006; McShane and Hastings 2009). For this reason, overparenting has been theorized as a later manifestation of oversolicitous parenting (Padilla-Walker and Nelson 2012; Segrin et al. 2012). Moreover, while restriction of independence may be problematic at any level of psychosocial development (Bayer et al. 2006; Gar and Hudson 2008; Grolnick et al. 2000; McShane and Hastings 2009), it may be especially problematic for young adults, as these individuals leave the home and are expected to function autonomously in their daily lives (Arnett 2004; Nelson and Barry 2005). Thus, overparenting appears to be uniquely troubling for the psychological development of young adult children.

In fact, empirical research has begun to demonstrate that overparenting is associated with a range of problematic outcomes (Schiffrin et al. 2014; Segrin et al. 2013). For example, studies have linked overparenting with a lower degree of self-efficacy, which may put young adults at risk while transitioning to college (Bradley-Geist and Olson-Buchanan 2014; van Ingen et al. 2015). Additionally, various studies have linked overparenting with poorer emotional health outcomes, including higher levels of anxiety (Segrin et al. 2013), greater depressive symptoms, and less satisfaction with life (Schiffrin et al. 2014). Studies by Odenweller et al. (2014) and Segrin et al. (2013) have also demonstrated overparenting to be predictive of poorer coping strategies among young adults, which may further exacerbate the impact of poorer emotional health.

Additionally, emerging research has begun to associate overparenting with narcissistic traits among young adults (Segrin et al. 2012, 2013). These findings are consistent with classical formulations of the etiology of narcissism which implicate the role of parental overcontrol and restrictions in leading to the development of narcissistic traits (Kohut 1977; Millon and Everly 1985; Rothstein 1979). For example, Kohut (1977) theorized that parental over-involvement and excessive control prevented children from being able to experience “optimal frustrations,” or opportunities for children to encounter difficulties when confronted with new experiences. Kohut (1977) believed failure to experience these optimal frustrations led to children who were dependent on others for validation of their own sense of self, which is a pattern of interpersonal functioning consistent with narcissism (Cain et al. 2008; Miller et al. 2011). Other theorists have arrived at similar conclusions, albeit through different theoretical interpretations. For example, Rothstein’s (1979) object-relations perspective posits that parental over-involvement is essentially a means for a parent to prevent a child from developing an independently functioning and healthy sense of self. Regardless of the specific theoretical interpretation, researchers have indicted various forms of parental over-control in the development of narcissism, including overparenting (Segrin et al. 2012, 2013), authoritarian parenting (Cramer 2015; Ramsey et al. 1996; Watson et al. 1992) and PPC (Givertz and Segrin 2014; Horton et al. 2006; Horton and Tritch 2014). Therefore, while classic theoretical approaches did not account for more modern manifestations of parental overcontrol and intrusiveness, such as “helicopter parenting” (Horton et al. 2006; Segrin et al. 2013), the intrusive and over-controlling nature of overparenting appears to be a plausible antecedent for the development of these narcissistic traits (Locke et al. 2012).

In fact, PPC may play an important role in the relationship between overparenting and young adult narcissism. PPC consists of specific parenting practices that interfere with the appropriate development of psychological and emotional health in children (Barber 1996). Regarded as a more insidious form of parenting (Barber 1996), specific examples of PPC practices include the withdrawal of love and the deployment of guilt tactics as forms of emotional manipulation (Barber 1996; Horton et al. 2006). Compared to overparenting, PPC is regarded as less well-intentioned. While both include efforts to control behavior, in the case of PPC, the intrusion is related to young adult children’s emotional functioning, whereas with overparenting, the intrusion seems to be more related to a restriction of autonomy (Padilla-Walker and Nelson 2012). Nevertheless, while these constructs remain empirically and conceptually distinct, overparenting and PPC are similar in that both include over-involvement, and they do not occur mutually exclusively (Padilla-Walker and Nelson 2012). We posit that PPC may be one tactic used by parents who engage in overparenting, and it is this mechanism which may be responsible for the narcissistic tendencies in young adults. Furthermore, in keeping with the perspectives of personality theorists who emphasize the role of parental intrusiveness in the etiology of narcissism (e.g., Kohut 1977; Rothstein 1979), researchers have linked PPC practices with the presence of narcissistic traits among young adults (Givertz and Segrin 2014; Horton et al. 2006; Horton and Tritch 2014).

Additionally, while studies have begun to link overparenting and PPC to narcissistic traits more broadly (Givertz and Segrin 2014; Horton et al. 2006; Segrin et al. 2012, 2013), research should continue to differentiate the predictive ability of these parenting approaches between specific narcissistic phenotypes (i.e., grandiose vs. vulnerable narcissism). Specifically, grandiose narcissism describes narcissistic functioning which is more openly arrogant and egotistical, with individuals possessing these traits displaying little awareness or concern for their problematic interpersonal patterns (Dickinson and Pincus 2003; Gabbard 1989). Conversely, vulnerable narcissism is characterized by a greater degree of anxious-avoidant behaviors (Dickinson and Pincus 2003; Miller et al. 2011). Excessive and intrusive parental involvement appears predictive of children who develop an overreliance on others for their sense of self (Horton et al. 2006), which is a pattern more similar to vulnerable narcissism compared to grandiose narcissism (Miller et al. 2011). Conversely, parental permissiveness and pampering has been linked to the development of grandiose narcissistic traits more specifically (Capron 2004; Imbesi 1999; Mechanic and Berry 2015; Otway and Vignoles 2006). As overparenting appears more closely representative of parenting which is over-controlling and intrusive (as it is not necessarily defined by an over-affection; Padilla-Walker and Nelson 2012), and as intrusiveness is a key component of PPC (Barber 1996), further examination of the predictive ability of both overparenting and PPC to separate narcissistic phenotypes appears warranted.

Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the mediating role of PPC between overparenting and narcissistic traits among young adults. Specifically, we hypothesized that (1) PPC would mediate the relationship between overparenting and narcissistic traits. Additionally, we sought to assess mediations separately for vulnerable and grandiose narcissistic phenotypes, and we hypothesized that (2) the mediating role of PPC between overparenting and narcissism would vary across vulnerable and grandiose narcissism.

Method

Participants

A total of 476 young adult college students from a mid-sized university in the southeastern United Stated were initially recruited for the present study. Validity checks were incorporated into study measures (Huang et al. 2012), which included removing participants who failed to respond in a specific manner to two directed response items (e.g., Answer “disagree” to this question; N = 1). Additionally, participants who completed study questionnaires within a time which would be considered unreasonable (i.e., 40 s for the PNI, 15 s for the PCS, 8 s for the HPS) were removed from further analyses (N = 40). An additional 55 participants were removed for failing to complete the study in its entirety, which resulted in a total of 96 participants being removed from the sample.

Therefore, a total of 380 participants (age: M = 20.1, SD = 1.72; age range: 18–26 years) were retained for the present study. Participants were predominantly female (78.9%), and either White/non-Hispanic (57.1%) or Black/African American (36.3%). All study participants were also asked to provide information on one primary caregiver, who they were to refer to in completing each measure of parenting behavior. Mothers were the most commonly identified primary caregiver (81.6%), followed by fathers (11.3%), grandmothers or other female family members (e.g., aunts; 3.4%), and “other” (3.7%). Participants were further asked to indicate “where [they] think [they] stand. relative to other people in the United States” on a 7-point scale (1 = Lowest to 7 = Highest) to assess socioeconomic status (Adler et al. 1994). Results demonstrated a slight positive skew (M = 3.17, SD = 1.68). Following a brief demographic questionnaire, participants completed all additional measures, which were presented in randomized order.

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. Upon providing informed consent, participants completed all study measures through SONA, an anonymous online survey system used for scheduling undergraduate research participants.

Measures

Overparenting

The Helicopter Parenting Scale (HPS; Padilla-Walker and Nelson 2012) is a five-item measure of overparenting, used to assess participants’ reports of their parents’ over-intrusive parenting behavior (e.g., “My parent intervenes in solving problems with my employers or professors;” “My parent solves any crisis or problem I might have”). Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all like him/her to 5 = A lot like him/her) and summed, with higher scores indicative of a greater degree of overparenting behaviors. Internal consistency was adequate (α = 0.80) for the present study.

Parental psychological control

The Psychological Control Scale (PCS; Schaeffer 1965) is an 8-item measure used to assess the psychological control practices of participants’ parents (e.g., “My parent is a person who brings up my past mistakes when he/she criticizes me;” “My parent is a person who is less friendly with me, if I do not see things his/her way”). Participants rate each item on a three-point Likert scale (1 = Not like him/her to 3 = A lot like him/her), with higher numbers indicative of a greater degree of PPC practices utilized. The PCS demonstrated adequate reliability for the present study (α = 0.87).

Narcissism

The Pathological Narcissism Inventory (PNI; Pincus et al. 2009) is a 52-item self-report measure of participants’ narcissistic tendencies. Each item is rated on a six-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all like me to 6 = Very much like me). The PNI consists of two main subscales (i.e., Narcissistic Grandiosity and Narcissistic Vulnerability) which are formed by taking the mean of 18 items and 34 items within the measure, respectively. A total score is then formed by taking the mean of these two combined subscales. Examples items include “Sacrificing for others makes me the better person” for Narcissistic Grandiosity, and “When people don’t notice me, I start to feel bad about myself” for Narcissistic Vulnerability. Reliability coefficients for the PNI total score, the Narcissistic Grandiosity subscale, and the Narcissistic Vulnerability subscale were 0.95, 0.87, and 0.94, respectively.

Data Analyses

Mediation analyses were utilized through Process (Hayes 2012), a macro for SPSS. Bootstrapping (10,000 samples) was used to test significance of indirect effects. Overparenting was entered as an independent variable in predicting narcissistic traits (separately for overall narcissism, grandiose narcissism, and vulnerable narcissism), with PPC as a hypothesized mediator.

Results

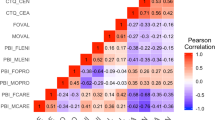

Bivariate correlations, means, and standard deviations are provided in Table 1. As expected, overparenting was significantly correlated with both PPC and total narcissism. No significant differences for participant sex were found for the HPS (F (1, 378) = 0.85, p = 0.057), the PCS (F (1, 378) = 0.65, p = 0.782), or the PNI (F (1, 378) = 0.21, p = 0.839). Results for mediation analyses can be seen in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Both overparenting (β = 1.34, 95% CI [0.06–2.11]) and PPC (β = 2.55, 95% CI [1.49–3.61]) were determined to be significant predictors of narcissistic traits when examined separately (see Fig. 1). In examining the combined mediation model, the direct effect of overparenting on narcissism remained significant (β = 1.11, 95% CI [0.40–1.81]), and the indirect effect of overparenting through PPC was also significant (β = 0.23, 95% CI [0.05–0.51]), indicating that PPC mediated the relationship between overparenting and narcissism (accounting for 17.1% of the relationship). The R-squared effect size was 0.012, and the Kappa-squared effect size was 0.034.

In examining grandiose narcissistic traits as the outcome variable, both overparenting (β = 0.41, 95% CI [0.15–0.67]) and PPC (β = 0.43, 95% CI [0.08–0.79]) were found to be significant predictors (see Fig. 2). Additionally, both the direct effect (β = 0.37, 95% CI [0.12–0.63]) and indirect effect (β = 0.04, 95% CI [0.004–0.11]) of overparenting through PPC on grandiose narcissism were significant, indicating that PPC is a mediator (accounting for approximately 9.8% of the relationship) between overparenting and grandiose narcissism, albeit to a seemingly lesser degree than between overparenting and total narcissism. The R2 and K2 effect sizes were 0.005 and 0.02, respectively.

Next, both overparenting (β = 0.93, 95% CI [0.44–1.42]) and PPC (β = 2.11, 95% CI [1.48–2.75]) were found to be significant predictors of vulnerable narcissistic traits (see Fig. 3). The direct effect of overparenting on vulnerable narcissism remained significant (β = 0.74, 95% CI [0.27–1.21]), while the indirect effect of overparenting through PPC was also significant (β = 0.19, 95% CI [0.03–0.40]), indicating that PPC serves as a mediator. Specifically, PPC accounted for approximately 20.4% of the relationship between overparenting and vulnerable narcissism, and the R2 and K2 effect sizes were 0.01 and 0.04, respectively.

Discussion

The present study examined the relationship between overparenting and narcissism, by demonstrating that PPC is a mediator in the relationship between overparenting and narcissistic traits among young adult college students. Additionally, PPC appears to account for the relationship between overparenting and both grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism separately, although this mediation appears slightly more robust when examined between overparenting and vulnerable narcissism. However, the differences in effect sizes between these two mediations were modest, and thus PPC appears to be better understood as a mediator between overparenting and narcissism more broadly, rather than vulnerable narcissism specifically.

These findings are consistent with previous research linking both overparenting (Segrin et al. 2012, 2013) and PPC (Givertz and Segrin 2014; Horton et al. 2006) to narcissistic tendencies, while also examining the latter as a mediator. While overparenting has traditionally been considered less malevolent than PPC (Barber 1996; Padilla-Walker and Nelson 2012), these findings suggest that the potential for parents to go too far in their desire to remain prominent and involved in their children’s lives appears to be linked to the development of narcissistic traits. For example, it is possible that as young adult children gain independence and spend greater time outside the home, parents’ over-involvement and intrusive overparenting practices may become exacerbated, and may even develop into more insidious psychological control practices. Of course, given the cross-sectional nature of the present study’s methodology, as well as the relatively small effect sizes, any conclusions regarding causality should remain tentative.

Additionally, in comparing the mediating role of PPC between overparenting and separate narcissistic phenotypes, the present study found a slightly stronger mediation for vulnerable narcissism, rather than grandiose narcissism, which is consistent with previous research implicating parental over-control in the development of vulnerable narcissistic traits (Horton et al. 2006; Kohut 1977). However, the mediation of PPC between overparenting and grandiose narcissism was also significant, which suggests that overparenting and PPC together may be better understood as predictive of narcissism more generally. This finding may be due to the high levels of warmth often observed in overparenting, despite overparenting not being assumed to be overly affectionate (Padilla-Walker and Nelson 2012). As an excess of affection and pampering has been linked to the development of grandiose narcissism (Capron 2004; Imbesi 1999; Mechanic and Berry 2015), these findings suggest the possibility for “helicopter” parents to in fact exhibit more affection than has traditionally been theorized (Padilla-Walker and Nelson 2012), perhaps as a means of justifying excessive control. Alternately, this finding is also likely attributable to the strong relationship and co-occurrence observed between vulnerable and grandiose narcissistic phenotypes (Pincus, 2013; Ronningstam 2009). Clearly, further research is needed before drawing any definite conclusions about the relationships between overparenting and separate narcissistic phenotypes. Additionally, data analysis methods which are able to directly compare separate mediations (e.g., invariance testing) are recommended for future studies.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The present study includes some pertinent limitations. All analyses are correlational in design, which precludes any definitive determination of causal ordering of variables. Given the reciprocal nature of parent-child relationships, it is possible that young adults’ narcissistic traits influence parenting practices, including parenting practices related to overcontrol. Similarly, the primary role of overparenting relative to PPC also cannot be assumed. Studies which utilize longitudinal designs are recommended for further clarifying any causal (or bidirectional) nature of study variables. It should be noted that all measures utilized within the present study (including reports of parenting practices) were completed by young adult children. While studies have suggested that young adults can accurately report on parenting practices exhibited by their parents (Barry et al. 2008), certainly the child’s perspective may be influenced by their own personality and experiences. Moreover, children may not have full access to the range of their parents’ relevant behaviors. Future studies may therefore wish to include direct parental reports.

Additionally, the present sample is limited in generalizability, with most participants consisting of female college students from a single university. Given the limited generalizability regarding college students, including in regard to socioeconomic status (McDonough 1997; Walpole 2003), additional studies should seek a more diverse sample of participants. However, it should be noted that no differences in participant sex were observed between study measures, and the participant SES appeared positively, rather than negatively skewed. Additionally, the racial diversity of the present study’s sample should be considered a strength.

Future research should explore additional possibilities regarding mediating relationships between overparenting and narcissism. For example, interpersonal dependency, which has been linked to both overparenting (Odenweller et al. 2014) and narcissistic traits (Kins et al. 2011, 2012), may be an additional mechanism in this relationship. Similarly, parental overvaluation may play a mediating role between overparenting and grandiose narcissism, in particular (Brummelman et al. 2015). Additional measures of parenting behaviors should also be included in future studies, in order to further differentiate the role of overparenting compared to other similar parenting styles, particularly in the development of narcissism.

In conclusion, findings from the present study suggest that the relationship between overparenting and narcissistic traits among young adult college students may be at least partially attributable to parents’ use of PPC practices (e.g., withholding love; utilization of guilt tactics). These findings provide further explanation for the relationship between “helicopter” parenting and narcissism among young adults, and should thus aid in future research and theorizing. While conclusions regarding any causal relationship between these variables should remain tentative, these findings are consistent with a growing body of research linking overparenting with narcissism.

References

Adler, N. E., Boyce, T., Chesney, M. A., Cohen, S., Folkman, S., & Kahn, R. L. (1994). Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient. American Psychologist, 49, 15–24.

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press.

Asghar, R. (2014, February 20). All work and no play makes your child…a narcissist. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/robasghar/2014/02/20/all-work-and-no-play-makes-your-child-a-narcissist/#802db315db87. Accessed 13 February 2018.

Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development, 67, 3296–3319. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.ep9706244861.

Barry, C. T., Frick, P. J., & Grafeman, S. J. (2008). Child versus parent reports of parenting practices: implications for the conceptualization of child behavioral and emotional problems. Assessment, 15(3), 294–303.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887–907.

Baumrind, D. (1967). Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 75(1), 43–88.

Bayer, J. K., Sanson, A. V., & Hemphill, S. A. (2006). Parent influences on early childhood internalizing difficulties. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27(6), 542–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2006.08.002.

Begley, S. (2013, September 20). ‘Helicopter Parents’ Crash Kids’ Job Interviews: What’s an Employer to Do? Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/theemploymentbeat/2013/09/20/helicopter-parents-crash-kids-job-interviews-whats-an-employer-to-do/#5372d5996963. Accessed 12 April 2017.

Bradley-Geist, J. C., & Olson-Buchanan, J. B. (2014). Helicopter parents: an examination of the correlates of over-parenting of college students. Education & Training, 56(4), 314–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-10-2012-0096.

Brummelman, E., Thomaes, S., Nelemans, S. A., de Castro, B. O., Overbeek, G., & Bushman, B. J. (2015). Origins of narcissism in children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of The United States of America, 112(12), 3659–3662.

Cain, N. M., Pincus, A. L., & Ansell, E. B. (2008). Narcissism at the crossroads: phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(4), 638–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.006.

Capron, E. W. (2004). Types of pampering and the narcissistic personality trait. The Journal of Individual Psychology, 60(1), 77–93.

Cramer, P. (2015). Adolescent parenting, identification, and maladaptive narcissism. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 32(4), 559–579. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038966.

Dickinson, K. A., & Pincus, A. L. (2003). Interpersonal analysis of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17(3), 188–207. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.17.3.188.22146.

Gabbard, G. O. (1989). Two subtypes of narcissistic personality disorder. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 53, 527–532.

Gar, N. S., & Hudson, J. L. (2008). An examination of the interactions between mothers and children with anxiety disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(12), 1266–1274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.08.006.

Givertz, M., & Segrin, C. (2014). The association between overinvolved parenting and young adults’ self-efficacy, psychological entitlement, and family communication. Communication Research, 4(8), 1111–1136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212456392.

Grolnick, W. C., Kurowski, C. O., Dunlap, K. G., & Hevey, C. (2000). Parental resources and the transition to Junior High. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 10(4), 465–488.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modelling. http://www.afhayes.com/ Accessed 2 September 2016.

Horton, R. S., Bleau, G., & Drwecki, B. (2006). Parenting Narcissus: What are the links between parenting and narcissism? Journal of Personality, 74(2), 345–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00378.x.

Horton, R. S., & Tritch, T. (2014). Clarifying the links between grandiose narcissism and parenting. Journal of Psychology, 148(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2012.752337.

Huang, J. L., Curran, P. G., Keeney, J., Poposki, E. M., & DeShon, R. P. (2012). Detecting and deterring insufficient effort responding to surveys. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(1), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9231-8.

Hyman, J. S., & Jacobs, L. F. (2010, May 12). 10 reasons parents should never contact college professors. US News & World Report. Web. https://www.usnews.com/education/blogs/professors-guide/2010/05/12/10-reasons-parents-shouldnever-contact-college-professors Accessed 10 April 2017.

Imbesi, L. (1999). The making of a narcissist. Clinical Social Work Journal, 27(1), 41–54.

Joyce, A. (2014, September 2). How helicopter parents are ruining college students. The Washington Post. Web. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/parenting/wp/2014/09/02/how-helicopter-parents-are-ruiningcollege-students/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.bc673131aa3b Accessed10 April 2017.

Kins, E., Soenens, B., & Beyers, W. (2012). Parental psychological control and dysfunctional separation–individuation: a tale of two different dynamics. Journal of Adolescence, 35(5), 1099–1109.

Kins, E., Soenens, B., & Beyers, W. (2011). ‘Why do they have to grow up so fast?’ Parental separation anxiety and emerging adults’ pathology of separation-individuation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(7), 647–664. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20786.

Kohut, H. (1977). The restoration of self. Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

LeMoyne, T., & Buchanan, T. (2011). Does “hovering” matter? Helicopter parenting and its effect on well-being. Sociological Spectrum, 31, 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2011.574038.

Locke, J. Y., Campbell, M. A., & Kavanagh, D. (2012). Can a parent do too much for their child? An examination by parenting professionals of the concept of overparenting. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 22(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2012.29.

McDonough, P. M. (1997). Choosing colleges: How social class and schools structure opportunity. New York: SUNY Press.

McShane, K. E., & Hastings, P. D. (2009). The new friends vignettes: Measuring parental psychological control that confers risk for anxious adjustment in preschoolers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33(6), 481–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025409103874.

Mechanic, K. L., & Barry, C. T. (2015). Adolescent grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: Associations with perceived parenting practices. Journal of Child and family Studies, 24(5), 1510–1518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9956-x.

Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Gaughan, E. T., Gentile, B., Maples, J., & Campbell, W. K. (2011). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis. Journal of Personality, 79(5), 1013–1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00711.x.

Millon, T., & Everly, G. (1985). Personality and its disorders: a biosocial learning approach. New York: Wiley.

Morrison, P. (2015, October 28). How ‘helicopter parenting’ is ruining America’s children. LA Times. Web. http://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-morrison-lythcott-haims-20151028-column.html Accessed 10 April 2017.

Nelson, M. K. (2010). Parenting out of control: Anxious parents in uncertain times. New York: New York University Press.

Nelson, L. J., & Barry, C. M. (2005). Distinguishing features of emerging adulthood: the role of self-classification as an adult. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20, 242–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558404273074.

Odenweller, K. G., Booth-Butterfield, M., & Weber, K. (2014). Investigating helicopter parenting, family environments, and relational outcomes for millennials. Communication Studies, 65(4), 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2013.811434.

Otway, L. J., & Vignoles, V. L. (2006). Narcissism and childhood recollections: a quantitative test of psychoanalytic predictions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(1), 104–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205279907.

Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Nelson, L. J. (2012). Black hawk down? Establishing helicopter parenting as a distinct construct from other forms of parental control during emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence, 35(5), 1177–1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.03.007.

Pincus, A. L. (2013). The Pathological Narcissism Inventory. In: J. S. Ogrodniczuk (Ed.) Understanding and treating pathological narcissism. (pp. 93–110). Washington, DC, US: AmericanPsychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14041-006.

Pincus, A. L., Ansell, E. B., Pimentel, C. A., Cain, N. M., Wright, A. G. C., & Levy, K. N. (2009). Initial construction and validation of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016530.

Ramsey, A., Watson, P. J., Biderman, M. D., & Reeves, A. L. (1996). Self-reported narcissism and perceived parental permissiveness and authoritarianism. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 157(2), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1996.9914860.

Ronningstam, E. (2009). Narcissistic personality disorder: facing DSM-V. Psychiatric Annals, 39(3), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20090301-09.

Rothstein, A. (1979). The theory of narcissism: an object-relations perspective. Psychoanalytic Review, 66, 35–47.

Rubin, K. H., Hastings, P. D., Stewart, S. L., Henderson, H. A., & Chen, X. (1997). The consistency and concomitants of inhibition: some of the children, all of the time. Child Development, 68, 467–483.

Schaefer, E. S. (1965). A configurational analysis of children’s reports of parent behavior. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 29, 552–557. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022702.

Schiffrin, H. H., Liss, M., Miles-McLean, H., Geary, K. A., Erchull, M. J., & Tashner, T. (2014). Helping or hovering? The effects of helicopter parenting on college students’ well-being. Journal of Child and family Studies, 23(1), 548–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9716-3.

Segrin, C., Givertz, M., Swaitkowski, P., & Montgomery, N. (2015). Overparenting is associated with child problems and a critical family environment. Journal of Child and family Studies, 24(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9858-3.

Segrin, C., Woszidlo, A., Givertz, M., & Montgomery, N. (2013). Parent and child traits associated with overparenting. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 32(6), 569–595. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2013.32.6.569.

Segrin, C., Woszidlo, A., Givertz, M., Bauer, A., & Murphy, M. T. (2012). The association between overparenting, parent-child communication, and entitlement and adaptive traits in adult children. Family Relations, 61(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00689.x.

van Ingen, D. J., Freiheit, S. R., Steinfeldt, J. A., Moore, L. L., Wimer, D. J., Knutt, A. D., Scapinello, S., & Roberts, A. (2015). Helicopter parenting: the effect of an overbearing caregiving style on peer attachment and self‐efficacy. Journal of College Counseling, 18(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2015.00065.x.

Walpole, M. (2003). Socioeconomic status and college: how SES affects college experiences and outcomes. Review of Higher Education, 27(1), 45–73. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2003.0044.

Watson, P. J., Little, T., & Biderman, M. D. (1992). Narcissism and parenting styles. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 9(2), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079344.

Author Contributions

N.A.W. designed and executed the study, ran the data analyses, and wrote the paper. B.C.N. collaborated with the design of the study and editing of the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of The University of Southern Mississippi’s Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Winner, N.A., Nicholson, B.C. Overparenting and Narcissism in Young Adults: The Mediating Role of Psychological Control. J Child Fam Stud 27, 3650–3657 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1176-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1176-3