Abstract

Recent Findings

Food Addiction (FA) is frequently observed in populations with obesity, and in eating disorders (ED) related to binge behaviours. However, the influence of FA in the treatment outcome of these conditions has been poorly explored.

Purpose of the Review

The aim of this review, is to reflect the influence of FA in the response to treatment, and other factors with it that could be related, in order to present treatment proposals and future research lines.

Summary

FA have been found to have a role in treatment outcome of obesity and ED patients, being as a predictive variable or as a mediator one. For those patients with obesity, FA have a negative influence on the weight loss process; in ED patients was associated with dropouts, and less levels of remission of the ED condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

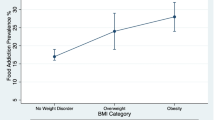

Food addiction (FA) is the term assigned to abnormal eating patterns that resemble behaviour found in addictive processes, either substance or behaviour based, most commonly conceptualized as a substance-based addiction to ultra-processed foods. Even though it is still under study as a construct itself or as a transdiagnostic condition in other eating and weight related problems, its study has recently attracted increased interest. A high prevalence has been found in eating disorders (ED) related to binge behaviours such as binge eating disorder (BED) (70%) and bulimia nervosa (BN) (95%), as well as in populations with obesity (18–24%). However, the influence of FA on these conditions has been poorly explored. The aim of the present review is to describe the influence of FA in the response to treatment and other factors with which it could be related, as to present treatment proposals and future research lines.

Influence of FA in Treatment Outcome

FA is frequently observed in populations with obesity [1] and has been proposed as one of the leading psychosocial correlates to weight-control failure [2]. Evidence has shown that more symptoms of FA, as defined by the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) [3], are associated with higher general psychopathology and more dysfunctional personality traits, and has strong implications for the treatment of individuals who are overweight and have obesity.

In this regard, several studies of individuals with obesity have explored the associations between FA and the outcome success of interventions. Table 1 shows a summary of studies included in this review evaluating the impact of FA on therapy response (original). Most of the results showed that the individuals that present FA symptoms have lower success rates after interventions, whether short-, medium-, or long term. Burmeister et al. observed that after an 18-week group behavioural weight loss intervention, adults who are overweight and have obesity having more FA symptoms at baseline lost a smaller percentage of body weight [4]. Similarly, in a sample of patients with obesity who sought bariatric surgery, the baseline FA criteria were linked to poorer weight loss after a 6-month dietary intervention [5]. Among a sample of women who were overweight and had obesity, Sawamoto et al. observed that participants who lose less weight during a 7-month Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and nutritional consultation intervention, had a tendency toward FA and were liable to regain weight after the treatment [6]. Their results also showed that successful weight maintenance was associated with lower YFAS scores by the end of the intervention. The same tendency of results was observed in older adults. After 1 year, following a Mediterranean diet intervention, FA predicted a higher Body Mass Index (BMI) and depression symptoms, and achieved a mediational role between impulsivity and BMI/depressive symptoms [7]. In the same sample, but with a longer follow-up of 3 years, the presence of FA at baseline resulted in a significantly greater weight regain [8] and appeared to influence treatment outcomes after obesity surgical interventions. In a sample of bariatric surgery patients, individuals who had higher levels of presurgical FA symptoms had poorer weight loss 1 year after following surgery, either gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy. Authors also observed that patients with a higher number of pre-surgical FA symptoms experienced different grades of stagnation in weight loss 3 months to a year after surgery [9].

Nonetheless, some authors have not found any association between the presence of FA and weight loss. After a 6-month lifestyle intervention, Lent et al. observed that the baseline presence of FA did not have a significantly contribution to the variance in weight loss [10]. Similar results were reported by Chao et al., that after a portion-controlled diet and lifestyle intervention, FA presence were not significantly associated with weight loss [11].

The presence of FA has also been linked to lower attendance and higher dropout rates for weight management programs. In an adolescent sample who were overweight and had obesity, after a 12-week multidisciplinary weight management program, Tompkins et al. observed that those who presented with FA had a significantly lower attendance and higher dropout rate [12]. These associations have also been noted in adult samples. Results from Fielding-Singh et al. showed that a baseline FA was linked to treatment failure after a 12-month weight loss intervention [2]. On the other hand, these findings differ from those of Lent et al., who found that an adult sample individuals who were overweight and had obesity FA symptoms at baseline did not mitigate the study attrition to a group-based lifestyle intervention [10].

All these findings may suggest that the presence of FA in patients with obesity could be an indicator of a bad prognosis for finding a successful weight loss process. However, even though the presence of FA seemed to have a negative influence on the treatment outcome, there was also evidence to suggest that these interventions may diminish FA symptoms. After a 22-month behavioural weight-loss program, Gordon et al. observed that as body weight decreased over time, so did FA symptoms. Their results also included a higher average YFAS score associated with lower weight loss [13]. FA prevalence also seemed to decrease after bariatric surgery. Sevinçer et al. observed a continuous decline in the prevalence of FA symptoms [14] in 6- and 12-months post-surgery follow-ups, regardless of the type of surgery: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or omega loop gastric bypass. The same observations were made by Dickhut et al., as FA symptomatology decreased significantly after bariatric surgery [15]. New technologies associated with medical sciences and patient treatment have also shown a positive effect. A recent study performed with adolescents participating in a weight loss intervention concluded that using an mHealth app (alone or in combination with coaching sessions) had a positive effect on reducing FA symptoms [16]. Furthermore, a telephone-based cognitive behavioural therapy (Tele-CBT) intervention for patients with obesity and FA reported significant improvements in FA symptoms scores 1 year after bariatric surgery [17].

A few studies have explored the impact of FA in specific treatment for eating disorders (Table 1), but to date there is no data on FA treatments. However, some interesting results are worth mentioning.

First, the comorbidities of ED and FA, with and without obesity, points to increased eating-disorder symptomatology, general psychopathology, dysfunctional personality traits, and other related variables that influence the worst treatment compliance and poor treatment outcomes. Shape concerns in patients with FA have been associated with higher severity of ED symptomatology [18]. In post-bariatric surgery patients, FA correlates with higher binge eating and general anxiety, as well as a lower general quality of life [17]. FA severity has also correlated positively with anxiety symptoms and negatively with quality of life, considering the psychological, physical and social domains [19]. All this may suggest that an additional focus for FA during traditional treatment would be helpful in those patients.

Munguía, et al. performed the first longitudinal study that identified three clusters of ED patients with FA, among other clinical variables and personality traits. The study followed 16 CBT group sessions of ED treatment and evaluated treatment response. The severity of the clusters was determined by the levels of FA symptomatology and the other variables. Treatment results followed a linear relation to the cluster severity. Of the three clusters, the third, (C3) had the best treatment results. The dysfunctional cluster, C1, presented the highest severity of eating symptomatology and general psychopathology as well as high levels of FA; the moderate cluster, C2, had higher levels of FA and middle levels of eating symptomatology and general psychopathology; finally, in C3, the functional cluster, the levels of all evaluated variables, included FA, were lower. C1 had the lowest rates of full remission; C2 the higher rates of dropouts; and C3 the highest rate of full remission [20].

These results are partially supported by Romero et al., who analyzed the predicted value of FA in treatment outcomes of BN and BED patients. Even if FA were not a direct predictor, it did mediate between treatment outcome and ED severity. Those patients with FA reported binge episodes more frequently than those without FA. This higher severity in ED symptomatology was associated with a poor prognosis among BED patients [21]. The positive correlation of FA with binge eating severity symptoms has already been mentioned in the literature [19].

The strongest association of FA with treatment outcome is also expressed inversely. Hilker et al. found that after six sessions of psychoeducational intervention in BN patients, FA levels decreased. In the same vein, high levels of FA were predictors of lower total abstinence of binging and purging episodes [22].

Other associated psychological aspects occurring alongside FA, largely explained in the current literature, such as high levels of impulsivity [23,24,25,26], emotion dysregulation [27], depression, low self-esteem and psychological distress [28] could be playing an important role in treatment response. However, based on the aforementioned studies and FA-related literature, no direct associations or predictive relationships had been explored yet. Nonetheless, it is possible to hypothesize that they may influence treatment response.

Treatment Proposal and Future Research Lines

Although FA influences treatment outcomes in patients with obesity and ED, each population may need a different treatment according to what has been mentioned in the present review. For patients with obesity and comorbid FA, weight reduction and treatment focusing on modifying caloric intake may be positive. Dickhut et al. followed bariatric surgery patients for 1 year after surgery, and found that both BMI and FA had decreased [15]. However, ED patients with FA, with or without obesity, seemed to have a higher degree of clinical variables associated with addiction [20], so other approaches may be needed.

Cognitive psychotherapies that focus on the cognitive processes involved in addictions have been suggested as new lines of treatment to increase long-term weight loss in patients with obesity, and to improve impulse control and emotional regulation. For example, contingency management, which is an intervention based on operant conditioning, has also been shown to be effective in reducing drug use and overeating in promoting weight loss [29].

In addition, psychoeducation about the dietary patterns implicated in addictive eating have been suggested as a positive treatment for this population [30]. The promotion of a healthier diet in patients with obesity and ED is a fundamental pillar of the treatment. To date, there is no sufficient evidence to support implementing an intervention to target FA. However, the reduction in the consumption of highly processed foods and high glycaemic index carbohydrates may be one valid approach. Such products are believed to promote addictive-like behaviours, which alter the reward-signalling and satiety cascade mechanisms [31]. Some authors have proposed, as a potential metabolic treatment, the use of a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet, to produce physiological changes believed to be involved in neurobiological and metabolic mechanism that could influence FA [32]. This type of diet consists of a low-carbohydrate, moderate-protein, and high-fat diet that results in the use of fatty acids and ketones rather than glucose as the primary source of energy. Recent results have shown that this dietary approach has had beneficial effect on metabolic parameters associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes, including weight control and management of lipid and glycaemic parameters [33]. The ketogenic state results in physiological changes that have an important effect on food intake, such as appetite suppression, decreased hunger, and higher satiety. Additionally, a reduction in circulating glucose and insulin promotes higher rates of lipolysis and reduce lipogenesis [34]. Changes in the rate of glycolysis promoted by this diet are believed to be involved in switching neurochemical signals and activating the mesolimbic reward pathway, which is implicated in addiction [35].

In the case of ED, treatment may consider different aspects. Wiedemann et al. also explored the FA influence on weight reduction treatment in patients with comorbid BED and obesity, founding that over 60% of participants met the FA criteria. This finding also showed a poorer acceptance of weight and shape (at clinical pathological levels), as well as a higher negative reaction to weighting instructions through treatment. These results were associated with greater levels of disordered eating following treatment, even if the degree of weight loss were similar to those with and without FA. Therefore, the comorbid population may benefit from both, a weight reduction and a clinical ED approach and addiction-related aspects [18].

Piccinni et al. suggested using addiction-based treatments, to address FA in patients with ED, including harm reduction or abstinence-based models instead of traditional CBT [36, 37]. Cognitive intervention that uses training tasks to reduce cognitive biases such as attention, response inhibition, and evaluative conditioning (affective bias) is one of the methods that continues to be explored as a treatment possibility for FA. In this sense, approaches that consider additional therapy aims of craving managements and increasing inhibitory control may be helpful [38]. Given the high levels of impulsivity in ED patients with comorbid FA, as well as disturbances in neural reward process, therapies aimed at reducing food-related impulsivity could be positive [39] as has been found in binge-related ED using this inhibitory training [40, 41].

Conclusions

Even though the study of FA increased over the past decade, there is still limited understanding of its treatment. As the present work has shown, some studies have identified risk factors or consequences associated with FA, as well as the influence of FA in treatment response. In ED patients with comorbid FA, personality traits, neural process, dietary patterns, emotion regulation, and others, may be considered when designing appropriate treatment. Moreover, since the presence of FA symptoms may be an indicator of a poor prognosis of weight loss interventions, health providers should screen for FA to implement specialized support for these individuals during the treatment.

References

Praxedes DRS, Silva-Júnior AE, Macena ML, Oliveira AD, Cardoso KS, Nunes LO, Monteiro MB, Melo ISV, Gearhardt AN, Bueno NB. Prevalence of food addiction determined by the Yale Food Addiction Scale and associated factors: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2022;30:85–95.

Fielding-Singh P, Patel ML, King AC, Gardner CD. Baseline psychosocial and demographic factors associated with study attrition and 12-month weight gain in the DIETFITS Trial. Obesity. 2019;27:1997–2004.

Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Appetite. 2009;52:430–6.

Burmeister JM, Hinman N, Koball A, Hoffmann DA, Carels RA. Food addiction in adults seeking weight loss treatment. Implications for psychosocial health and weight loss. Appetite. 2013;60:103–10.

Guerrero Pérez F, Sánchez-González J, Sánchez I, et al. Food addiction and preoperative weight loss achievement in patients seeking bariatric surgery. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2018;26:645–56.

Sawamoto R, Nozaki T, Nishihara T, Furukawa T, Hata T, Komaki G, Sudo N. Predictors of successful long-term weight loss maintenance: a two-year follow-up. Biopsychosoc Med. 2017;11:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-017-0099-3.

Mallorquí-Bagué N, Lozano-Madrid M, Vintró-Alcaraz C, et al. Effects of a psychosocial intervention at one-year follow-up in a PREDIMED-plus sample with obesity and metabolic syndrome. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):9144. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-021-88298-1.

Camacho-Barcia L, Munguía L, Lucas I, et al. Metabolic, affective and neurocognitive characterization of metabolic syndrome patients with and without food addiction. Implications for Weight Progression. Nutrients. 2021;13(8):2779. https://doi.org/10.3390/NU13082779

Miller-Matero LR, Bryce K, Saulino CK, Dykhuis KE, Genaw J, Carlin AM. Problematic eating behaviors predict outcomes after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2018;28:1910–5.

Lent MR, Eichen DM, Goldbacher E, Wadden TA, Foster GD. Relationship of food addiction to weight loss and attrition during obesity treatment. Obesity. 2014;22:52–5.

Chao AM, Wadden TA, Tronieri JS, Pearl RL, Alamuddin N, Bakizada ZM, Pinkasavage E, Leonard SM, Alfaris N, Berkowitz RI. Effects of addictive-like eating behaviors on weight loss with behavioral obesity treatment. J Behav Med. 2019;42:246–55.

Tompkins CL, Laurent J, Brock DW. Food addiction: a barrier for effective weight management for obese adolescents. Child Obes. 2017;13:462–9.

Gordon EL, Merlo LJ, Durning PE, Perri MG. Longitudinal changes in food addiction symptoms and body weight among adults in a behavioral weight-loss program. Nutrients. 2020;12:3687.

Sevinçer GM, Konuk N, Bozkurt S, Coşkun H. Food addiction and the outcome of bariatric surgery at 1-year: prospective observational study. Psychiatry Res. 2016;244:159–64.

Dickhut C, Hase C, Gruner-Labitzke K, Mall JW, Köhler H, de Zwaan M, Müller A. No addiction transfer from preoperative food addiction to other addictive behaviors during the first year after bariatric surgery. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2021;29:924–36.

Vidmar AP, Yamashita N, Fox DS, Hegedus E, Wee CP, Salvy SJ. Can a behavioral weight-loss intervention change adolescents’ food addiction severity? Child Obes. 2022;18:206–12.

Cassin S, Leung S, Hawa R, Wnuk S, Jackson T, Sockalingam S. Food addiction is associated with binge eating and psychiatric distress among post-operative bariatric surgery patients and may improve in response to cognitive behavioural therapy. Nutrients. 2020;12:1–12.

Wiedemann AA, Ivezaj V, Gueorguieva R, Potenza MN, Grilo CM. Examining self-weighing behaviors and associated features and treatment outcomes in patients with binge-eating disorder and obesity with and without food addiction. Nutrients. 2020;13:1–11.

Oliveira E, Kim HS, Lacroix E, et al. The clinical utility of food addiction: characteristics and psychosocial impairments in a treatment-seeking sample. Nutrients. 2020;12:3388.

Munguía L, Gaspar-Pérez A, Jiménez-Murcia S, Granero R, Sánchez I, Vintró-Alcaraz C, Diéguez C, Gearhardt AN, Fernández-Aranda F. Food addiction in eating disorders: a cluster analysis approach and treatment outcome. Nutrients. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/NU14051084.

Romero X, Agüera Z, Granero R, et al. Is food addiction a predictor of treatment outcome among patients with eating disorder? Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2019;27:700–11.

Hilker I, Sánchez I, Steward T, et al. Food addiction in bulimia nervosa: clinical correlates and association with response to a brief psychoeducational intervention. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2016;24:482–8.

Pivarunas B, Conner BT. Impulsivity and emotion dysregulation as predictors of food addiction. Eat Behav. 2015;19:9–14.

Brunault P, Ducluzeau PH, Courtois R, Bourbao-Tournois C, Delbachian I, Réveillère C, Ballon N. Food addiction is associated with higher neuroticism, lower conscientiousness, higher impulsivity, but lower extraversion in obese patient candidates for bariatric surgery. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53:1919–23.

Wolz I, Hilker I, Granero R, Jiménez-Murcia S, Gearhardt AN, Dieguez C, Casanueva FF, Crujeiras AB, Menchón JM, Fernández-Aranda F. “Food addiction” in patients with eating disorders is associated with negative urgency and difficulties to focuson long-term goals. Front Psychol. 2016;7:61.

Maxwell AL, Gardiner E, Loxton NJ. Investigating the relationship between reward sensitivity, impulsivity, and food addiction: a systematic review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2020;28:368–84.

Wolz I, Granero R, Fernández-Aranda F. A comprehensive model of food addiction in patients with binge-eating symptomatology: the essential role of negative urgency. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;74:118–24.

Gearhardt AN, White MA, Masheb RM, Morgan PT, Crosby RD, Grilo CM. An examination of the food addiction construct in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:657–63.

Carter A, Hendrikse J, Lee N, Yücel M, Verdejo-Garcia A, Andrews ZB, Hall W. The neurobiology of “food addiction” and its implications for obesity treatment and policy. Annu Rev Nutr. 2016;36:105–28.

Gearhardt A, White M, Potenza M. Binge eating disorder and food addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4:201–7.

Schulte EM, Avena NM, Gearhardt AN. Which foods may be addictive? The roles of processing, fat content, and glycemic load. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117959. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117959.

Sethi Dalai S, Sinha A, Gearhardt AN. Low carbohydrate ketogenic therapy as a metabolic treatment for binge eating and ultraprocessed food addiction. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2020;27:275–82.

Choi YJ, Jeon SM, Shin S. Impact of a ketogenic diet on metabolic parameters in patients with obesity or overweight and with or without type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2020;12:1–19.

Paoli A, Rubini A, Volek JS, Grimaldi KA. Beyond weight loss: a review of the therapeutic uses of very-low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diets. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67:789–96.

Lennerz B, Lennerz JK. Food addiction, high-glycemic-index carbohydrates, and obesity. Clin Chem. 2018;64:64–71.

Piccinni A, Bucchi R, Fini C, Vanelli F, Mauri M, Stallone T, Cavallo ED, Claudio C. Food addiction and psychiatric comorbidities: a review of current evidence. Eat Weight Disord - Stud Anorexia, Bulim Obes. 2021;26:1049–56.

Treasure J, Leslie M, Chami R, Fernández-Aranda F. Are trans diagnostic models of eating disorders fit for purpose? A consideration of the evidence for food addiction. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2018;26:83–91.

Beitscher-Campbell H, Blum K, Febo M, Madigan MA, Giordano J, Badgaiyan RD, Braverman ER, Dushaj K, Li M, Gold MS. Pilot clinical observations between food and drug seeking derived from fifty cases attending an eating disorder clinic. J Behav Addict. 2016;5:533–41.

Schag K, Leehr EJ, Meneguzzo P, Martus P, Zipfel S, Giel KE. Food-related impulsivity assessed by longitudinal laboratory tasks is reduced in patients with binge eating disorder in a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1–12.

Giel KE, Speer E, Schag K, Leehr EJ, Zipfel S. Effects of a food-specific inhibition training in individuals with binge eating disorder—findings from a randomized controlled proof-of-concept study. Eat Weight Disord. 2017;22:345–51.

Turton R, Nazar BP, Burgess EE, Lawrence NS, Cardi V, Treasure J, Hirsch CR. To go or not to go: a proof of concept study testing food-specific inhibition training for women with eating and weight disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2018;26:11–21.

Acknowledgements

We thank CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support. This manuscript and research was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (PSI2015‐68701‐R), by the Delegacion del Gobierno para el plan Nacional sobre Drogas (2017I067 and 2019I), by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII; FIS PI20/132 and PI17/01167), and co‐funded by FEDER funds/European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), a way to build Europe. CIBERObn is an initiative of ISCIII.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Human and Animal Rights

All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and complied with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards, and international/national/institutional guidelines).

Conflict of Interest

FFA received consultancy honoraria from Novo Nordisk and editorial honoraria as EIC from Wiley. The rest of the authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Food Addiction

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Camacho-Barcia, L., Munguía, L., Gaspar-Pérez, A. et al. Impact of Food Addiction in Therapy Response in Obesity and Eating Disorders. Curr Addict Rep 9, 268–274 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-022-00421-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-022-00421-y