Abstract

Background

Motor neurone disease (MND) is a devastating condition which greatly diminishes patients’ quality of life and limits life expectancy. Health technology appraisals of future interventions in MND need robust data on costs and utilities. Existing economic evaluations have been noted to be limited and fraught with challenges.

Objective

The aim of this study was to identify and critique methodological aspects of all published economic evaluations, cost studies, and utility studies in MND.

Methods

We systematically reviewed all relevant published studies in English from 1946 until January 2016, searching the databases of Medline, EMBASE, Econlit, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and the Health Economics Evaluation Database (HEED). Key data were extracted and synthesised narratively.

Results

A total of 1830 articles were identified, of which 15 economic evaluations, 23 cost and 3 utility studies were included. Most economic studies focused on riluzole (n = 9). Six studies modelled the progressive decline in motor function using a Markov design but did not include mutually exclusive health states. Cost estimates for a number of evaluations were based on expert opinion and were hampered by high variability and location-specific characteristics. Few cost studies reported disease-stage-specific costs (n = 3) or fully captured indirect costs. Utilities in three studies of MND patients used the EuroQol EQ-5D questionnaire or standard gamble, but included potentially unrepresentative cohorts and did not consider any health impacts on caregivers.

Conclusion

Economic evaluations in MND suffer from significant methodological issues such as a lack of data, uncertainty with the disease course and use of inappropriate modelling framework. Limitations may be addressed through the collection of detailed and representative data from large cohorts of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Existing economic evidence in motor neurone disease (MND) is limited with respect to data on resource use, costs, and health utilities, as well as how models reflect disease progression. |

Future studies should focus on generating longitudinal data from representative population groups; confirming the validity of models in how they represent the natural course of disease progression; and analysing cost and utility data according to defined health states. |

The evidence accumulated in this review provides a basis for the advancement of economic studies in MND. |

1 Introduction

Motor neurone disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (hereafter referred to as MND) is a progressively degenerative condition. The disease affects the motor neurones in the brain and spinal cord which severely impacts patients’ basic functioning such as walking, communication and breathing, and can additionally adversely affect cognitive abilities [1]. These impair patients’ health-related quality of life (QoL) significantly [2]. Current treatment for MND is focused on palliative care with the aim of sustaining a high QoL for as long as possible. Estimated survival time from diagnosis is between 3 and 5 years [3]. Due to the extent of the disability, patients with MND have dependency on carers to help with their daily needs. This need is usually met by partners or family members of the patient and, due to the nature of care required, places a significant physical and emotional burden on their lives [4].

MND is a rare disease with incidence and prevalence rates varying by country and region. A recent systematic review of its epidemiology reported European, North American and Asian incidence rates of 2.08, 1.8 and 0.46 per 100,000 population per year, respectively [5]. Prevalence rates were reported as 5.4, 3.4 and 2.01 per 100,000 population in these regions. In the UK there are an estimated 4000 people living with MND [6].

The economic costs of MND are high, both in terms of direct medical costs to health providers, non-medical costs incurred by patients and their caregivers and indirect costs through loss of employment. Costs vary over the trajectory of the condition, and are dependent on disease manifestation, progression and duration of survival [7]. To date, however, there has been a limited number of economic evaluations of interventions for MND, with the majority focused on riluzole, which is the only disease-modifying drug currently approved. With the prospect of new treatments for MND [8], there will be an increased need for robust economic data and modelling framework for assessing their cost effectiveness. The aim of this article is to systematically review sources of costs and utilities, and provide a critique of the data and methods used in economic studies of MND.

2 Methods

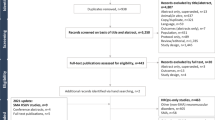

This review was conducted according to the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidance for undertaking reviews in health care [9], and reported with alignment to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline, where applicable [10].

2.1 Search Strategy

Systematic searches were undertaken to identify economic evaluations, studies detailing costs and studies which estimated health-state utilities in patients with MND. The search terms are listed in Appendix 1 (see electronic supplementary material). The databases searched (from 1946 to January 2016) were Medline, EMBASE, Econlit, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), and the Health Economics Evaluation Database (HEED). The references of included papers were checked for any further articles for inclusion.

2.2 Inclusion Criteria and Study Selection

The review included studies reporting economic evaluations, detailed costs and health utilities relating to MND. Studies not published in English were excluded from the review. Titles were screened independently by two reviewers. Articles deemed by either reviewer to meet the inclusion criteria were screened independently on abstract with any disagreements resolved by a third independent reviewer. The full texts were retrieved and assessed according to the inclusion criteria.

2.3 Data Extraction

Data forms were created for the economic evaluations and cost studies included in the review and key details relating to the methods of included studies extracted and tabulated. Cost and utility value data from these studies were also recorded along with the corresponding 2014/15 value of costs in pounds sterling (GBP). Currency conversions were undertaken using data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) [11] and costs were inflated using the Hospital and Community Health Services (HCHS) pay and prices index [12].

2.4 Analysis of Results

Important methodological features were summarised and critiqued within a narrative review.

3 Results

A total of 1830 articles were identified, of which 60 were considered potentially relevant and 41 eligible for inclusion in the review. The PRIMSA flow diagram shows the number of included studies at the various stages of the review process (Fig. 1).

3.1 Study Characteristics

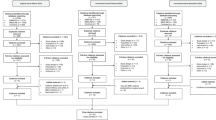

The systematic review identified 13 economic evaluations, 2 updates of economic evaluations, 23 cost studies, and 3 studies reporting health utilities (Tables 1, 2, 3).

The majority of economic evaluations were conducted in the UK [16–20, 24, 26, 27] (n = 8) followed by North America [13, 15, 22, 23] (n = 4), Italy [14, 21] (n = 2) and Israel [25] (n = 1), showing the high concentration of studies originating in a few countries. Eight studies reported a cost–utility analysis [15–20, 22, 23], six studies performed cost-effectiveness analyses [13, 14, 21, 24, 26, 27], and one study carried out a cost–benefit analysis [25]. Eleven evaluations adopted a third-party payer perspective, such as national health services [13, 14, 16–21, 24, 26, 27], one study adopted a societal viewpoint [25], while three studies presented results from both perspectives [15, 22, 23]. More recent economic evaluations tended to report only direct medical costs to health service providers.

Studies focusing solely on costs were predominantly North American [28, 30, 33, 34, 37, 40, 43, 44, 46, 48–50] (n = 12) or European [31, 32, 36, 38, 39, 41, 42, 45, 47] (n = 9) with two from Asia [29, 35]. Cost studies adopted a health services perspective [28, 31, 35, 39, 43, 44, 46–48] (n = 9), societal perspective [33, 40, 41, 45, 49] (n = 5) or both [29, 30, 32, 34, 36–38, 42, 50] (n = 9). Studies reported costs for a variety of categories, including treatments [30, 32–34, 36, 37, 41, 42, 44, 45, 47, 48] (n = 12), places or methods of delivering care [28, 29, 31, 35, 38, 39, 43, 46] (n = 8), home ventilation [49, 50] (n = 2) and mobility devices [40] (n = 1). However, only three studies reported disease-stage-specific costs [29, 42, 47].

Studies of health-state utility reported disease-stage utilities by five (mild, moderate, severe, terminal and death) [51, 52] or two (mild and severe) [42] health states. All studies elicited utilities from patients with MND based on structured interviews with MND patients [51, 52], or from a postal questionnaire [42]. These used a combination of the EuroQol EQ-5D-3L, visual analogue scale (VAS) and standard gamble to measure utility.

3.2 Modelling Methodology

Eight studies, including the more recent evaluations, used a Markov architecture which allows for progressive decline in motor function to be modelled [15–20, 22, 23]. The models attach costs and utilities to health states and allow patient cohorts to pass through states until they reach the (absorbing) death state or a pre-determined severely low functioning level. Health states within these models were defined by Appel amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) scores [22] or according to forced vital capacity scores (FVC) [23] and based on an adaptation of Rivere et al. [53] who first modelled MND using a Markov model [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Transition probabilities of subjects through the various health states were calculated using data from randomised control trials (RCTs) of riluzole [15–20], recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-1 (rhlGF-1) [22] and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [23].

Models used various techniques to estimate survival beyond the data available from RCTs. Three studies used a linear function [16–18] and one an exponential function [22] to extrapolate trial data. Although these were deemed to have fit the data well by study authors, they are not the correct functional form for survival analysis. The constant hazard rate model, which gives the exponential distribution, assumes the property of no-aging [58]. One study used a Weibull model [20] (based on a power hazard rate model). One study used a Gompertz model (exponential hazard rate model), without presenting goodness of fit [21] and one study used both a Weibull and a Gompertz model [19] to explore differences in model fit.

3.3 Resource Use and Costs

Twenty-two studies reported direct costs only [13, 14, 16–21, 24, 26–28, 31, 35, 39, 40, 43–48], while 16 reported both direct and indirect costs [15, 22, 23, 25, 29, 30, 32–34, 36–38, 41, 42, 49, 50].

Studies which included direct costs estimated resource use from medical records [13–15, 28, 31, 32, 37–39, 43] (n = 10), RCTs [19–27] (n = 9), surveys [30, 37, 40, 42, 45, 49, 50] (n = 7), utilization patterns based on consultation with neurologists with MND expertise [16–18, 47, 48] (n = 5), national databases [36, 46] (n = 2), structured interviews with patients [33, 41] (n = 2), insurance claim data [34] (n = 1) and a mixture of medical records and insurance claim data [35] (n = 1). Indirect costs were obtained via patient surveys [15, 23, 30, 32, 34, 37, 38, 42, 49, 50] (n = 10) and interviews [22, 29, 33, 41] (n = 4), and national databases [25, 36] (n = 2).

Unit costs came from institutional records [13, 14, 28, 29, 31–33, 35, 38, 39, 43, 45, 46] (n = 13), national databases [15, 21, 24–27, 36, 37, 42, 44] (n = 10), the published literature [16–20, 23] (n = 6), surveys [30, 40, 41, 49, 50] (n = 5), consultation with MND experts [47, 48] (n = 2), insurance claim data [34] and estimation of drug costs from the manufacturer [22].

Some studies defined standard care costs [16, 19, 20, 22, 25, 27] (n = 6), but descriptions varied by location and setting.

Indirect unit costs were gathered by surveys [22, 23, 29, 30, 33, 34, 38, 41, 49, 50] (n = 10), national databases [15, 36, 37, 42] (n = 4) and using the national minimum [32] and average wage [25].

Key cost data used in economic evaluations in MND are presented in Table 3. Many of the cost inputs originate from the same sources, suggesting a limited evidence base [16–20]. Furthermore, costs varied by location, with the annual price of riluzole, for example, reported as £6429 in the UK and £9487 in the US (2014/15 adjusted values in GBP [£]). Table 4 presents the main data from cost studies in MND. Costs and cost categories include length of hospital stays [35, 43, 46], ventilation [30, 49, 50], complementary medicines [45] and mobility [40]. Differences in costs within countries may be attributed to type of treatments considered, methods of data collection or source populations [30, 37, 43]. The diverse cost estimates and categories highlight the challenges of generalising results, with the need for more detailed and encompassing cost-of-illness studies.

3.4 Health State Utilities

Eleven studies included the use of health-state utility values (HSUVs), of which six [15–20] took their values from Kiebert et al. [51] who elicited utilities based on standard gamble using structured interviews in the UK. However, this study is limited in size, with only 77 MND patients involved and with some health states being represented by as few as 15 patients. Two other studies used hypothetical utility values which were not based on any empirical evidence, but rather intended for illustrative purposes [23, 24]. One study estimated utilities using the standard gamble technique administered to a panel of healthcare professionals with experience of treating patients with MND [22]. A study in Spain used postal administration of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-VAS in a sample of 36 patients [42]. The most recent utility study, which was set in the UK with a sample of 214 patients, also used the EQ-5D-3L along with the EQ-VAS to elicit utilities longitudinally [52].

Studies which included HSUVs varied in their description of health states. A five-stage model was used in Kiebert et al. [15–20, 51] based on the earlier work of Riviere et al. [53]. The full definitions of health states are presented in Box 1. Jones et al. [52] used the King’s ALS clinical stage framework consisting of five states; stage 1: diagnosis and involvement of first region, stage 2: involvement of second region, stage 3: involvement of third region, stage 4: need for intervention (gastrostomy or non-invasive ventilation) and stage 5: death. Ackerman et al. [22] used a five-state model defined by Appel ALS scores which cover aspects of speech, respiratory function, swallowing, dressing and feeding, need for assistive device, work status and medical care. By contrast, Ringel et al. [23] used a four-health-stage model based solely on FVC scores. López-Bastida et al. [42] used a simple two-stage classification of the disease with patients either in the mild state (not in need of caregiver help) or the severe state (in need of caregiver help).

Health-state utility data in the economic evaluations came from a limited number of sources [15–20, 22], with some reliant on hypothetical data [23, 24], highlighting a lack of evidence in this area (Table 3). Furthermore, as descriptions of health states are not uniform [15–20, 22, 23], utility values varied significantly, especially in some progressively low functional states. In the most recent UK evaluations [16–20], the terminal state value is 0.45, compared with −0.53 in the study by Ackerman et al. [22]. Differences in health-utility values appear to be more divergent than the health descriptions used in these evaluations [22, 53].

3.5 Uncertainty Analysis

Most economic evaluations considered parameter uncertainty by application of one-way sensitivity analysis around benefits/utilities [16–22, 24] (n = 9), costs [16–20, 25] (n = 6) and tolerance of patient cohorts to treatment [15] (n = 1). Three studies performed two-way sensitivity analysis to jointly assess the contribution of both costs and benefits/utilities on cost effectiveness [16–18], while only one study carried out a full probabilistic sensitivity analysis [23]. Scenario analyses considered uncertainty in costs, health benefits and survival [21, 26] (n = 2). Two studies attempted to account for structural uncertainty with alternative models [19, 21], while another study assessed the impact of different patient demographics on cost effectiveness (of riluzole) [26]. Uncertainty analysis in the studies showed that the main drivers of cost effectiveness in MND treatments were drug costs and estimated extension in survival.

4 Discussion

With the prospect of new treatments for MND on the horizon, including the neuroprotective agent edaravone, tyrosine kinase inhibitor masitinib and gene and stem cell therapies [59–62], there will be an increased need for robust data and modelling framework to assess their cost effectiveness. Most economic evaluations are based on Markov models with disease-specific stages which aim to trace disease progression and its effects on patients and their use of healthcare resources. The often used five-stage disease progression model [15–20, 51, 53] has methodological issues with respect to its clinical classification system of health states. It conflates recency of diagnosis with severity of illness and would lead to some patients being misplaced in health states which may not reflect the true costs or benefits related to their disease status. It therefore fails to meet the Markov assumption of mutual exclusivity. The Kings ALS clinical staging model, as used in Jones et al. [52], provides health state descriptions which are mutually exclusive, and therefore potentially making it more appropriate for use in Markov modelling.

Costs can vary considerably between stages of MND [29, 42, 47]. However, only a few studies have reported disease-stage-specific costs. Munsat et al. [47] is the most cited among UK economic evaluations, but the estimates from this analysis are based on resource utilization taken from interviews with four neurologists with experience of treating MND, and needs updating. The authors highlight the variation in cost estimates between each expert, reflecting differences in clinical practice. Economic evaluations included in our review did not consider changes to the annual costs of standard palliative care by disease stage as it was claimed that these would be unaffected by treatment. This assumption has been untested empirically.

Several studies have reported or estimated indirect costs associated with MND [15, 22, 23, 25, 29, 30, 32–34, 36–38, 41, 42, 49, 50]. While there are recognised challenges relating to the measurement of lost productivity by both patients and their caregivers [63–65], the importance is more so in MND as patients have a higher earning potential than the national averages [36], owing to the average age of onset peaking around the mid-fifties and the fact that the disease presents more in men [1].

Instruments used to measure the health-related QoL in patients with MND need to be sensitive enough to capture changes across the disease course, have the required dimensions which apply to the condition and robust psychometric properties. The EQ-5D-3L has been used as a generic measure, but concerns have been highlighted over its ability to record an accurate representation of the complexity surrounding QoL in MND. The narrow conceptual components of the EQ-5D-3L often restrict utility measurement and fail to include symptom characteristics that are salient to those with MND, such as respiratory function and communicative ability [66, 67]. Issues such as sensitivity of the EQ-5D-3L to clinical changes in the disease course and their resulting impact on utilities, and floor effects, further limit the usefulness of the instrument. One undertaking which could help in this regard is using the EQ-5D-5L, which improves the range of responses and mitigates the floor effects to some degree [68, 69].

The ALS Utility Index is a disease-specific instrument which has been developed through surveying a general population sample, but is yet to be validated in MND patients [70]. This index also focuses solely on the physical functioning aspect of MND, with no domain for emotional wellbeing or pain. In spite of its drawbacks, it represents an advance that should prompt further research in this area.

Patients’ preferences may vary with respect to the management of the different symptoms experienced. Direct utility estimation in MND has been limited to the standard gamble approach. Kiebert et al. [51] found that utility scores, based on standard gamble, were higher for disease stage 3 (needs assistance in two or three regions) than disease stage 2 (mild defect in three regions) in the ALS Health State Scale; despite the descriptions of disease stage 3 appearing to be significantly worse. However, when the same sample of patients completed the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire, the results showed a progressive lowering of health-stage utilities along the disease course. Furthermore, this study elicited significantly different utility score estimations for standard gamble and EQ-5D-3L methods. The standard gamble results from this study featured in the riluzole manufacturer’s submission to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [18], as well as the more recent economic evaluations in MND [15–17]. Alternative methods of direct utility estimation, such as time trade-off or the use of choice-based techniques such as the Discrete Choice Experiment (DCE), have hitherto not featured in MND studies.

MND has important and significant impacts on informal caregivers, such as family members [71–73]. While there is debate concerning the inclusion of the QoL effects on carers in economic evaluations, and methodological challenges relating to the measurement, valuation and incorporation of QoL impacts on carers [63–65], the lack of consideration for carer utilities in MND is apparent. Further challenges include consideration of how carers’ productivity is affected by the disease, especially in the latter stages of the condition when more help is required. The inclusion of caregiver utilities in a cost-effectiveness framework for MND could affect conclusions of economic evaluations of treatments if those treatments are near cost-effectiveness threshold values, as was the case for riluzole, and prove to impact on carers’ QoL [63].

The strengths of the review are in its inclusiveness and in-depth analysis of the methods and findings from economic and cost-of-illness studies. We are unaware of any other review of the economic evidence in MND, but acknowledge some unpublished articles such as HTA reports in jurisdictions outside the UK may have been omitted. We excluded non-English studies, which may have been available to European, Latin American and Asian reimbursement authorities (for instance, in relation to riluzole).

The challenges presented in this review highlight the current methodological limitations faced by health economists in MND. These issues, such as the need to incorporate the broader impact of treatments on patients’ QoL and the uncertainty surrounding the current empirical evidence, transcend into other disease areas, notably multiple sclerosis and dementia [74, 75]. This would indicate that the issues pertinent to the economic analysis of MND treatments are far reaching, and require due consideration in other health economic work.

5 Conclusion

Current economic studies in MND are limited in many ways, including the comprehensiveness and reliability of cost studies, a lack of research reporting health-state utilities across the disease course, and poorly defined health states. Our review has highlighted a clear need for up-to-date and methodologically rigorous economic data for unbiased assessment of the cost effectiveness of future interventions in MND. We have also identified a need for a robust evaluation framework in MND. Future research should target these limitations, and utilise data from large, longitudinal studies, such as the UK Trajectories of Outcome in Neurological Conditions (TONiC) study [76], which has recruited over 800 patients to complete cost and QoL questionnaires. Improvements in economic studies in MND will result in more informative guidance on healthcare resource allocation when new, and inevitably expensive, interventions are licensed.

References

Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Cheah BC, Turner MR, Eisen A, Hardiman O, Burrell JR, Zoing MC. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2011;377(9769):942–55.

Hogg KE, Goldstein LH, Leigh PN. The psychological impact of motor neurone disease. Psychol Med. 1994;24(3):625–32.

Talbot K. Motor neuron disease: the bare essentials. Pract Neurol. 2009;9:303–9.

Miyashita M, Narita Y, Sakamoto A, Kawada N, Akiyama M, Kayama M, Suzukamo Y, Fukuhara S. Health-related quality of life among community-dwelling patients with intractable neurological diseases and their caregivers in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65(1):30–8.

Chiò A, Logroscino G, Traynor BJ, Collins J, Simeone JC, Goldstein LA, White LA. Global epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review of the published literature. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;41(2):118–30.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Motor neurone disease: assessment and management. 2016. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng42. Accessed 19 Sept 2016.

Leigh PN, Abrahams S, Al-Chalabi A, Ampong MA, Goldstein LH, Johnson J, Lyall R, Moxham J, Mustfa N, Rio A, Shaw C, Willey E, King’s MND Care and Research Team. The management of motor neurone disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(Suppl 4):iv32–47.

Motor Neurone Disease Association. MND treatment trials. http://www.mndassociation.org/research/mnd-research-and-you/treatment-trials/. Accessed 3 Aug 2016.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: University of York; 2009. https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf. Accessed 3 Aug 2016.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). Exchange rate archives. http://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/data/param_rms_mth.aspx. Accessed 17th Oct 2016.

Curtis L, Burns A. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2015. http://www.pssru.ac.uk/project-pages/unit-costs/2015/index.php. Accessed 17th Oct 2016.

Alanazy H, White C, Korngut L. Diagnostic yield and cost-effectiveness of investigations in patients presenting with isolated lower motor neuron signs. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2014;15(5–6):414–9.

Vitacca M, Paneroni M, Trainini D, Bianchi L, Assoni G, Saleri M, Gilè S, Winck JC, Gonçalves MR. At home and on demand mechanical cough assistance program for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89(5):401–6.

Gruis K, Chernew M, Brown D. The cost-effectiveness of early noninvasive ventilation for ALS patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:58.

Tavakoli M. Disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Identifying the cost-utility of riluzole by disease stage. Eur J Health Econ. 2002;3(3):156–65.

Tavakoli M, Malek M. The cost utility analysis of riluzole for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the UK. J Neurol Sci. 2001;191(1–2):95–102.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Riluzole (Rilutek) for the treatment of Motor Neurone Disease (TA20); 2001.

Bryan S, Barton P, Burls A. The clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of riluzole for motor neurone disease—an update. Birmingham: West Midlands Development and Evaluations Service, Department of Public Health and Epidemiology. University of Birmingham. 2000.

Stewart A, Sandercock J, Bryan S, Hyde C, Barton PM, Fry-Smith A, Burls A. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of riluzole for motor neurone disease: a rapid and systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5(2):1–97.

Messori A, Trippoli S, Becagli P, Zaccara G. Cost effectiveness of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Italian Cooperative Group for the Study of Meta-Analysis and the Osservatorio SIFO sui Farmaci. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;16(2):153–63.

Ackerman SJ, Sullivan EM, Beusterien KM, Natter HM, Gelinas DF, Patrick DL. Cost effectiveness of recombinant human insulin-like growth factor I therapy in patients with ALS. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;15(2):179–95.

Ringel SP, Woolley JM, Culebras A. Economic analysis of neurological services. Eur J Neurol. 1999;6(Suppl 2):s21–4.

Gray AM. ALS/MND and the perspective of health economics. J Neurol Sci. 1998;160(Suppl 1):S2–5.

Ginsberg GM, Lev B. Cost-benefit analysis of riluzole for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Pharmacoeconomics. 1997;12(5):578–84.

Booth-Clibborn N, Best L, Stein K. Riluzole for motor neurone disease. Development and Evaluation Committee Report No. 73. Wessex Institute for Health Research and Development. 1997.

Chilcott J, Golightly P, Jefferson D, et al. The use of riluzole in the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sheffield: Trent Institute for Health Services Research. University of Leicester, Nottingham and Sheffield. 1997.

Boylan K, Levine T, Lomen-Hoerth C, Lyon M, Maginnis K, Callas P, Gaspari C, Tandan R, ALS Center Cost Evaluation W/Standards and Satisfaction (Access) Consortium. Prospective study of cost of care at multidisciplinary ALS centers adhering to American Academy of Neurology (AAN) ALS practice parameters. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2015;17(1-2):119–27.

Oh J, An JW, Oh SI, Oh KW, Kim JA, Lee JS, Kim SH. Socioeconomic costs of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis according to staging system. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2015;16(3–4):202–8.

Obermann M, Lyon M. Financial cost of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a case study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2015;16(1–2):54–7.

Connolly S, Heslin C, Mays I, Corr B, Normand C, Hardiman O. Health and social care costs of managing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): an Irish perspective. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2015;16(1–2):58–62.

Athanasakis K, Kyriopoulos II, Sideris M, Rentzos M, Evdokimidis J, Kyriopoulos J. Investigating the economic burden of ALS in Greece: a cost-of-illness approach. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2015;16(1–2):63–4.

Gladman M, Dharamshi C, Zinman L. Economic burden of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a Canadian study of out-of-pocket expenses. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2014;15(5–6):426–32.

Larkindale J, Yang W, Hogan PF, Simon CJ, Zhang Y, Jain A, Habeeb-Louks EM, Kennedy A, Cwik VA. Cost of illness for neuromuscular diseases in the United States. Muscle Nerve. 2014;49(3):431–8.

Kang SC, Hwang SJ, Wu PY, Tsai CP. The utilization of hospice care among patients with motor neuron diseases: the experience in Taiwan from 2005 to 2010. J Chin Med Assoc. 2013;76(7):390–4.

Jennum P, Ibsen R, Pedersen SW, Kjellberg J. Mortality, health, social and economic consequences of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a controlled national study. J Neurol. 2013;260(3):785–93.

Muscular Dystrophy Association. Cost of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, and spinal muscular atrophy in the United States. Muscular Dystrophy Association, The Lewin Group Inc. 2012. https://www.mda.org/sites/default/files/Cost_Illness_Report.pdf. Accessed 3 Aug 2016.

Lopes de Almeida JP, Pinto A, Pinto S, Ohana B, de Carvalho M. Economic cost of home-telemonitoring care for BiPAP-assisted ALS individuals. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012;13(6):533–7.

Vitacca M, Comini L, Assoni G, Fiorenza D, Gilè S, Bernocchi P, Scalvini S. Tele-assistance in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: long term activity and costs. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2012;7(6):494–500.

Ward AL, Sanjak M, Duffy K, Bravver E, Williams N, Nichols M, Brooks BR. Power wheelchair prescription, utilization, satisfaction, and cost for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: preliminary data for evidence-based guidelines. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(2):268–72.

Schepelmann K, Winter Y, Spottke AE, Claus D, Grothe C, Schröder R, Heuss D, Vielhaber S, Mylius V, Kiefer R, Schrank B, Oertel WH, Dodel R. Socioeconomic burden of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, myasthenia gravis and facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. J Neurol. 2010;257(1):15–23.

López-Bastida J, Perestelo-Pérez L, Montón-Alvarez F, Serrano-Aguilar P, Alfonso-Sanchez JL. Social economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Spain. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10(4):237–43.

Elman LB, Stanley L, Gibbons P, McCluskey L. A cost comparison of hospice care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and lung cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2006;23(3):212–6.

Forshew DA, Bromberg MB. A survey of clinicians’ practice in the symptomatic treatment of ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2003;4(4):258–63.

Wasner M, Klier H, Borasio GD. The use of alternative medicine by patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2001;191(1–2):151–4.

Lechtzin N, Wiener CM, Clawson L, Chaudhry V, Diette GB. Hospitalization in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: causes, costs, and outcomes. Neurology. 2001;56(6):753–7.

Munsat TL, Rivière M, Swash M, Leclerc C. Economic burden of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the United Kingdom. J Med Econ. 1998;1(1–4):235–45.

Klein LM, Forshew DA. The economic impact of ALS. Neurology. 1996;47(4 Suppl 2):S126–9.

Sevick MA, Kamlet MS, Hoffman LA, Rawson I. Economic cost of home-based care for ventilator-assisted individuals. Chest. 1996;109(6):1597–606.

Moss AH, Oppenheimer EA, Casey P, Cazzolli PA, Roos RP, Stocking CB, Siegler M. Patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis receiving long-term mechanical ventilation. Advance care planning and outcomes. Chest. 1996;110(1):249–55.

Kiebert GM, Green C, Murphy C, Mitchell JD, O’Brien M, Burrell A, Leigh PN. Patients’ health-related quality of life and utilities associated with different stages of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2001;191(1–2):87–93.

Jones AR, Jivraj N, Balendra R, Murphy C, Kelly J, Thornhill M, Young C, Shaw PJ, Leigh PN, Turner MR, Steen IN, McCrone P, Al-Chalabi A. Health utility decreases with increasing clinical stage in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2014;15(3–4):285–91.

Riviere M, Meininger V, Zeisser P, Munsat T. An analysis of extended survival in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis treated with riluzole. Arch Neurol. 1998;55(4):526–8.

Lacomblez L, Bensimon G, Leigh PN, Guillet P, Powe L, Durrleman S, Delumeau JC, Meininger V. A confirmatory dose-ranging study of riluzole in ALS. Neurology. 1996;47(6 Suppl 4):S242–50.

Bensimon G, Lacomblez L, Meininger V. A controlled trial of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. ALS/Riluzole Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(9):585–91.

Lai EC, Felice KJ, Festoff BW, Gawel MJ, Gelinas DF, Kratz R, Murphy MF, Natter HM, Norris FH, Rudnicki SA. Effect of recombinant human insulin-like growth factor I on progression of ALS: a placebo-controlled study. Neurology. 1997;49(6):1621–30.

Bradley W. A controlled trial of recombinant methionyl human BDNF in ALS: the BDNF Study Group (Phase III). Neurology. 1999;52(7):1427–33.

Latimer N. NICE DSU technical support document 14: survival analysis for economic evaluations alongside clinical trials—extrapolation with patient-level data. Report by the Decision Support Unit; 2014.

Henriques A, Pitzer C, Schneider A. Neurotrophic growth factors for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: where do we stand? Front Neurosci. 2010;4:32.

Mitsumoto H. ALS clinical trials. https://psg-mac43.ucsf.edu/als/Mitsumoto,%20H%20(AAN)%208BS-006-97.pdf. Accessed 3 Aug 2016.

Goutman SA, Chen KS, Feldman EL. Recent advances and the future of stem cell therapies in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics. 2015;12(2):428–48.

Scarrott JM, Herranz-Martín S, Alrafiah AR, Shaw PJ, Azzouz M. Current developments in gene therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15(7):935–47.

Al-Janabi H, Flynn TN, Coast J. QALYs and carers. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(12):1015–23.

Rowen D, Dixon S, Hernández-Alava M, Mukuria C. Estimating informal care inputs associated with EQ-5D for use in economic evaluation. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17(6):733–44.

Tranmer JE, Guerriere DN, Ungar WJ, Coyte PC. Valuing patient and caregiver time: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(5):449–59.

Epton J, Harris R, Jenkinson C. Quality of life in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease: a structured review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10(1):15–26.

Jenkinson C, Peters M, Bromberg MB. Quality of life measurement in neurodegenerative and related conditions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011.

Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, Gudex C, Niewada M, Scalone L, Swinburn P, Busschbach J. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(7):1717–27.

Greene ME, Rader KA, Garellick G, Malchau H, Freiberg AA, Rolfson O. The EQ-5D-5L improves on the EQ-5D-3L for health-related quality-of-life assessment in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(11):3383–90.

Beusterien K, Leigh N, Jackson C, Miller R, Mayo K, Revicki D. Integrating preferences into health status assessment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the ALS utility index. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2005;6(3):169–76.

Goldstein LH, Adamson M, Jeffrey L, Down K, Barby T, Wilson C, Leigh PN. The psychological impact of MND on patients and carers. J Neurol Sci. 1998;160(Suppl 1):S114–21.

Goldstein LH, Adamson M, Barby T, Down K, Leigh PN. Attributions, strain and depression in carers of partners with MND: a preliminary investigation. J Neurol Sci. 2000;180(1–2):101–6.

Lerum SV, Solbrække KN, Frich JC. Family caregivers’ accounts of caring for a family member with motor neurone disease in Norway: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:22.

Hawton A, Shearer J, Goodwin E, Green C. Squinting through layers of fog: assessing the cost effectiveness of treatments for multiple sclerosis. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(4):331–41.

Knapp M, Iemmi V, Romeo R. Dementia care costs and outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(6):551–61.

Trajectories of Outcomes in Neurological Conditions (TONiC). https://tonic.thewaltoncentre.nhs.uk/tonic-mnd. Accessed 6 Aug 2016.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Motor Neurone Disease Association UK for their funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

AM, CAY and DH declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributions

AM, CAY and DH contributed substantially to the conception and design of the work. All authors made contributions to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. AM drafted the paper and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content, and gave their final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moore, A., Young, C.A. & Hughes, D.A. Economic Studies in Motor Neurone Disease: A Systematic Methodological Review. PharmacoEconomics 35, 397–413 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0478-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0478-9