Abstract

Gout and renal impairment are frequent comorbidities, with both conditions strongly associated with hyperuricaemia. The management of gout involves treating and preventing gout flares, and reducing serum urate levels to eliminate the urate crystal deposits in the joints. Although the overall treatment of gout is very similar in patients with or without renal impairment, special precautions must be taken to avoid adverse effects related to renal impairment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Gout is fully curable …

Gout is characterized by monosodium urate (MSU) crystal deposits in the joint that trigger an inflammatory response, producing episodes of intense pain and swelling [1]. The development of MSU crystal deposits is silent and potentially very prolonged; diagnosing gout before the first gout attack by screening for the crystals is currently difficult [2]. Nevertheless, MSU crystal formation is fully reversible and gout, therefore, is considered a curable disease [3].

Gout treatment and prevention strategies in patients with renal impairment must be approached carefully due to the complexity of renal impairment, and drug selection, dosage modification and the impact of the treatment on the existing renal impairment should be considered [4]. This article provides a summary of the treatment and management of gout in patients with renal impairment, as reviewed by Pascual et al. [4].

… and often co-exists with renal impairment

MSU crystal deposits form and persist with prolonged hyperuricaemia, which occurs most often from insufficient serum urate (SU) elimination [1]; as such, renal impairment contributes greatly to the development of gout [4]. However, hyperuricaemia may also contribute to renal impairment, with multiple studies showing a positive correlation between SU levels and the risk of kidney disease [4]; similarly, patients with gout have a greater risk of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [5].

Gout treatment in patients with renal impairment, therefore, requires particular caution in terms of selecting the best treatment at the most appropriate dosage [4]. Creatinine clearance (CrCL) should be assessed beforehand in order to select the most appropriate drug and dosage [4].

Focus on lowering serum urate …

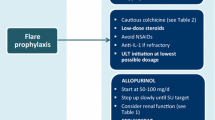

At the emergence of gout symptoms, treatment to eliminate MSU crystal deposits should be administered until all signs of gout are cleared and, if necessary, continued during treatment and prophylaxis for gout flares (Fig. 1) [4]. As MSU crystals dissolve completely at normal SU levels, the primary aim of gout treatment is to lower SU levels, typically with SU-lowering drugs (Table 1) [4]. Such treatment decreases the risk of gout flares, often without the need for additional prophylactic treatments [4].

Treating gout in patients with renal impairment, as suggested by Pascual et al. [4]

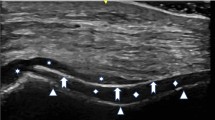

SU levels should be reduced to < 0.30 mmol/L (< 5 mg/dL) in patients with severe gout [3]. Although MSU crystals dissolve faster when SU levels at low, lowering SU to < 0.18 mmol/L (< 3 mg/dL) for a period of years is advised against due to a possible increased risk of neurological disorders [3]. It is difficult to determine when MSU crystals have been fully dissolved, and ultrasounds may be useful in identifying any remaining deposits [4]. Once the deposits have been dissolved, SU levels should be maintained at < 0.36 mmol/L (< 6 mg/dL), the level at which new crystals cannot form [6].

… but start slow

In general, it is crucial to slowly ease into SU reduction therapy; gout flares are more likely (and at greater severity) if SU levels drop too sharply at the beginning of treatment [4]. Starting treatment with SU-lowering drugs at lower dosages (which can be gradually increased as appropriate) is particularly imperative for gout patients with renal impairment due to the potential for kidney-related adverse effects to occur (Table 1) [4].

Allopurinol and febuxostat are xanthine-oxidase inhibitors, and are the drugs most commonly used to treat hyperuricaemia (Table 1) [4]. If xanthine-oxidase inhibitor monotherapy is unable to adequately reduce SU levels, a uricosuric drug may be added to reduce MSU crystal formation and improve excretion of SU (Table 1) [4], especially in patients with severe gout and limited treatment options [7]. Uricosuric drugs may be less effective in lowering SU levels as renal impairment worsens [4]. Uricase and pegloticase (Table 1), are highly effective in reducing SU levels, but are associated with high immunogenicity [8]. Their use should be limited to the treatment of selected severe cases [4].

If necessary, haemodialysis is a highly effective in removing SU and may also clear tophi [4]. However, as sudden drops in SU may trigger gout attacks, post-dialysis SU levels should be examined before administering SU-lowering drugs, which should typically be administered at lower dosages in patients undergoing haemodialysis [4].

Address gout flares with caution

Untreated gout flares generally subside within 2 weeks [4]. Colchicine is an effective treatment for gout flares in patients with normal renal function, but its use has been discouraged in those with renal impairment (Table 2). Exposure to colchicine increases in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment [14], leading to a greater risk of colchicine-related toxicity [15]. Oral, parenteral and intra-articular corticosteroids seem to be a safe and effective alternative to colchicine in this population (Table 2), but their use in certain patients is contraindicated, not recommended or requires caution [4].

With interleukin (IL)-1 activation being the trigger for gout-related inflammation, the anti-IL-1 agents canakinumab and anakinra are also effective in gout patients with renal impairment (Table 2) [4]. For example, used on-demand to treat and prevent gout flares, subcutaneous canakinumab 150 mg was more effective than on-demand intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg [16], and a single dose of canakinumab ≥ 50 mg was more effective than daily colchicine 0.5 mg as prophylaxis [17].

Importantly, despite the general effectiveness of NSAIDs in treatment gout flares and as prophylaxis, they should not be used to treat gout in patients with renal impairment [4].

Evidence suggests that prophylaxis should continue for > 6 months, although the optimal duration of prophylaxis not yet clear [4]. In more severe cases, such as frequently flaring severe gout, combination therapy with multiple drugs (e.g. colchicine + a corticosteroid) may be temporarily required [4].

Educate to improve treatment adherence

Patients should be thoroughly educated about gout and its treatment, and any misconceptions about the condition should be addressed [4]. Proper education may improve adherence to gout treatment. For example, in patients with gout who received individualized education, 90% were adherent to gout treatment after 5 years, with 85% of these taking their prescribed medication ≥ 6 days a week [22].

Take home messages

When managing gout in patients with renal impairment:

-

Consider the renal function of the patient, and select the best treatment at the most appropriate dosage.

-

Titrate allopurinol dosages to achieve target SU levels (outdated practice to base dosage on CrCL).

-

Avoid or use low dosages of colchicine.

-

Be aware that many uricosuric drugs are not widely available, and may be of limited effectiveness in this patient population.

-

Educate patients about gout and its treatment to improve treatment adherence.

References

Chen LX, Schumacher HR. Gout: an evidence-based review. J Clin Rheumatol. 2008;14(5 Suppl):S55–62.

Newberry SJ, FitzGerald JD, Motala A, et al. Diagnosis of gout: a systematic review in support of an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(1):27–36.

Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):29–42.

Pascual E, Sivera F, Andrés M. Managing gout in the patient with renal impairment. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(4):263–73.

Yu KH, Kuo CF, Luo SF, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease associated with gout: a nationwide population study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(2):R83.

Perez-Ruiz F, Calabozo M, Herrero-Beites AM, et al. Improvement of renal function in patients with chronic gout after proper control of hyperuricemia and gouty bouts. Nephron. 2000;86(3):287–91.

Reinders MK, van Roon EN, Jansen TL, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of urate-lowering drugs in gout: a randomised controlled trial of benzbromarone versus probenecid after failure of allopurinol. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(1):51–6.

Yang X, Yuan Y, Zhang CG, et al. Uricases as therapeutic agents to treat refractory gout: current states and future directions. Drug Dev Res. 2012;73(2):66–72.

Chao J, Terkeltaub RA. Critical reappraisal of allopurinol dosing, safety, and efficacy for hyperuricemia in gout. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009;11:1135–40.

Saito Y, Stamp LK, Caudle KE, Hershfield MS, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines for human leukocyte antigen B (HLA-B) genotype and allopurinol dosing: 2015 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;99(1):36–7.

White WB, Saag KG, Becker MA, et al. Cardiovascular safety of febuxostat or allopurinol in patients with gout. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(13):1200–10.

Pui CH. Rasburicase: a potent uricolytic agent. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2002;3(4):433–42.

Mejia-Chew C, Torres RJ, de Miguel E, et al. Resolution of massive tophaceous gout with three urate-lowering drugs. Am J Med. 2013;126(11):e9–10.

Wason S, Mount D, Faulkner R. Single-dose, open-label study of the differences in pharmacokinetics of colchicine in subjects with renal impairment, including end-stage renal disease. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34(12):845–55.

Bardin T, Richette P. Impact of comorbidities on gout and hyperuricaemia: an update on prevalence and treatment options. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):123.

Lyseng-Williamson KA. Canakinumab: a guide to its use in acute gouty arthritis flares. BioDrugs. 2013;27(4):401–6.

Schlesinger N, Mysler E, Lin HY, et al. Canakinumab reduces the risk of acute gouty arthritis flares during initiation of allopurinol treatment: results of a double-blind, randomised study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(7):1264–71.

Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and antiinflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(10):1447–61.

Fernandez C, Noguera R, Gonzalez JA, et al. Treatment of acute attacks of gout with a small dose of intraarticular triamcinolone acetonide. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(10):2285–6.

Andrés M, Begazo A, Sivera F, et al. Intraarticular triamcinolone plus mepivacaine provides a rapid and sustained relief for acute gouty arthritis [abstract no. AB0815]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1182.

Terkeltaub RA. Clinical practice: gout. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(17):1647–55.

Rees F, Jenkins W, Doherty M. Patients with gout adhere to curative treatment if informed appropriately: proof-of-concept observational study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(6):826–30.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The article was adapted from Drugs & Aging 2018;35(4):263–73 [4] by employees of Adis/Springer, who are responsible for the article content and declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The preparation of this review was not supported by any external funding.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adis Medical Writers. Be cautious when treating gout in patients with renal impairment. Drugs Ther Perspect 35, 24–28 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-018-0568-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-018-0568-1