Abstract

This paper reviews economic and medical research publications to determine the extent to which the measures applied in Spain to control public health spending following the economic and financial crisis that began in 2008 have affected healthcare utilization, health and fairness within the public healthcare system. The majority of the studies examined focus on the most controversial cutbacks that came into force in mid-2012. The conclusions drawn, in general, are inconclusive. The consequences of this new policy of healthcare austerity are apparent in terms of access to the system, but no systematic effects on the health of the general population are reported. Studies based on indicators of premature mortality, avoidable mortality or self-perceived health have not found clear negative effects of the crisis on public health. The increased demands for co-payment provoked a short-term cutback in the consumption of medicines, but this effect faded after 12–18 months. No deterioration in the health of immigrants after the onset of the crisis was unambiguously detected. The impact of the recession on the general population in terms of diseases associated with mental health is well documented; however, the high levels of unemployment are identified as direct causes. Therefore, social policies rather than measures affecting the healthcare system would be primarily responsible. In addition, some health problems have a clear social dimension, which seems to have become more acute during the crisis, affecting in particular the most vulnerable population groups and the most disadvantaged social classes, thus widening the inequality gap.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Some health problems have a clear social dimension, which seems to have become more acute during the crisis. |

The public health system has borne a disproportionate share of the burden of spending cuts provoked by the crisis, but it has managed to avoid irreversible deterioration. The most tangible consequences of healthcare spending cuts and austerity measures concern problems of access to healthcare, both for specific population groups (undocumented immigrants) and for patients in general (longer waiting lists). |

The studies have common limitations: use of cross-sectional data and no consideration of lags between the cause (economic recession) and its effects (mortality, morbidity). To better estimate the effects of the crisis on the populations health, up-to-date data of cohorts from clinical records and registries would be needed. |

No attempt has thus far been made in Spain to reform the health system with a view to achieving long-term sustainability in response to the 2008 recession and for preventing future recessions. |

1 Introduction

The Spanish Society of Public Health and Healthcare Administration (SESPAS) 2014 report on crisis and health [1] concluded that the main effects of the financial and economic recession on health and fairness arose from changes in the social determinants of health. The crisis started in Spain in 2008 with a downturn in gross domestic product (GDP) for two consecutive quarters. Rising unemployment and poverty, as a result of the crisis, are health risk factors that are much more intense than cutbacks in health spending. Therefore, austerity policies and spending cuts are only part of the cause. It is this area that has received the least attention in the scientific literature. Just as a driver may suffer a blind spot, the impact of healthcare spending cuts on access, uptake and public health has largely remained under the radar. In late 2013, the Catalan authorities created a crisis and healthcare observatory that regularly publishes status reportsFootnote 1 monitoring certain indicators. This observatory analyses macroeconomic indicators and their association with health and its social determinants, but does not evaluate health spending cutbacks or their effects on access, healthcare utilization or public health in general.

Causal relationships are not easy to establish empirically. The economic recession is reflected in the deterioration of macroeconomic and labour market indicators, which can stimulate changes in public, economic, social and health policies. However, with observational data alone, we cannot establish whether the cause of any deterioration in the population’s health is attributable to markets or governments or—among the latter—whether it would be attributable to those responsible for health or to public policy in general and the welfare state in particular. In these troubled waters, cutbacks in public health spending in developed countries have been associated with increases in mortality [2], and many medical research publications have defended the assertion that “austerity kills” [3, 4], an idea that has become established in many sectors of society, including healthcare personnel [5] and in electoral programs. During the crisis, the word austerity (i.e., sobriety, the absence of excess) acquired a pejorative connotation [6]. A qualitative study of 13 European cities, including Madrid and Barcelona [7], found that many local politicians believed spending cuts exacerbated the crisis and reduced the options available to the local system.

We review published economic and medical research on spending cuts and austerity policies in Spain and their consequences in terms of health and fairness. Spain is interesting as a case study because the economic and financial crisis that began in 2008 had a major impact on the country, provoking greater unemployment and a more unequal distribution of income than in other European countries.

We selected articles published in English or Spanish in peer-reviewed journals between 2008 and April 2016 that included the keywords “austerity” or “crisis” or “cutbacks” and “health” and “Spain” or “Spanish” in the title or abstract. The databases consulted were PubMed, Google Scholar and Econlit. We also considered grey literature and searched the websites of health and crisis observatories in CataloniaFootnote 2 and Andalusia.Footnote 3 From this initial selection, we then extracted reviews and original studies focusing on or including Spain. Editorials and opinion pieces were excluded, as were publications not referring specifically to austerity policies or health spending cutbacks. We also considered the additional references included in the bibliography of each article selected. In total, 151 items were initially selected, of which 28 met the inclusion criteria and were retained. The selection of review items was conducted independently by the two authors, who discussed any differences in this respect and reached a consensus. Table A1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) contains the summary of the reviewed studies with methods and main results.

In the following section, we present the austerity policies implemented in Spain since the beginning of the crisis, after which we examine the effects of austerity policies on access to health services, health outcomes and fairness. Finally, we discuss the lessons learned from the crisis.

2 Austerity Policies

Spain officially entered recession in the second quarter of 2008,Footnote 4 but the public health sector was not hit by budget cuts until 2 years later. Real GDP fell by 5.2 % between 2009 and 2013, and the unemployment rate rocketed from 8.6 % in the fourth quarter of 2007 to 25.7 % in the fourth quarter of 2013. For the first time, Europe imposed budgetary discipline on health spending centres, which had been accustomed to systematically exceeding budget ceilings. Even the Spanish Constitution was amended in 2011, in record time, to impose constitutional limits on the public deficit, introducing the concept of budgetary stability.

Between 2009 and 2013, according to the 2013 report on the economic and financial performance of the public sector [8], public health spending in absolute terms declined by 14 %, while total public spending fell by 6 %. Therefore, the health sector bore a disproportionately large share of the financial adjustment to the crisis. Cutbacks in public health spending began in 2010 and accelerated from then until 2013, after which the process slowed. The crisis was addressed primarily by means of cuts in not only investment but also current spending on personnel and supplies [9]. The Autonomous Communities (devolved regional authorities), which have full autonomy in healthcare management, were affected to varying degrees by the restrictions, according to their financial situation, and regional disparities in public healthcare spending increased significantly during the economic crisis.

The first anti-crisis measures were indiscriminate and generalised, affecting outpatient prescription drugs (unilateral reductions in prices and commercial margins in 2010) [10], staffing (increased working hours, salary cuts, drastic reductions in rates of retirement replacement) and real investments, which plunged. Subsequently, the cuts became more selective and differentiated between the regions. In 2013, a “Choose Wisely” campaign, an initiative of the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality, was launched to encourage professional associations, at all levels, to avoid practices that provided no therapeutic value.Footnote 5

The most far-reaching regulatory measure was Royal Decree-Law (RDL) 16/2012 of 20 April,Footnote 6 which came into force on 1 July 2012 and limited access to public health for undocumented immigrants, undermining the principle of universal coverage, and imposed new co-payments for drugs (pensioners, who had previously been exempt from this requirement, were now included) and for other benefits such as non-emergency ambulance transport.

Nevertheless, even in comparison with countries where the crisis was relatively mild, such as the UK and Germany, the measures adopted for the Spanish healthcare system were not especially drastic [11].

It is noteworthy that, in contrast to the drive to reduce outpatient pharmaceutical spending, no clear-cut initiatives were taken to control spending on hospital drugs, despite evidence that Spain is buying treatments for cancer and other diseases at prices far exceeding any reasonable incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, paying up to half a million euro per quality-adjusted life-year [12].

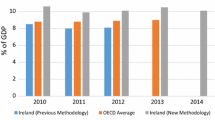

In 2014, no further restrictive measures were approved, and some existing ones were relaxed. Therefore, this date is taken as concluding the austerity cycle in the Spanish healthcare system. However, the government’s 2015–2018 National Reform Plan, which it has assured the EU authorities will be implemented, still forecasts public health spending as being reduced from 6.3 % of GDP before the crisis to 5.4 % by 2018.

3 Impact on Healthcare Service Access and Uptake

According to the economic report presented in the above-mentioned RDL 16/2012, which restricted access to the public health system for undocumented immigrants and non-resident EU citizens, spending would be cut by nearly one billion euro, and some 873,000 non-residents would be excluded from public healthcare. Although some population groups—immigrants aged <18 years; immigrants during pregnancy, delivery and the post-partum period; and those requiring emergency care after serious illness or injury—continued to have access to public healthcare, there remain many obstacles in practice [13] and the Autonomous Communities apply the legislation in different ways. Some, in fact, have simply not applied the restricted access to immigrants or have employed subterfuges to maintain access despite the new restrictive regulations.

One of the arguments put forward for these reactions, apart from the expression of solidarity, is that restricting access to health services for immigrants may have cost externalities, since the incidence of infectious disease is much higher among immigrants. For example, in Catalonia in 2014, the incidence of tuberculosis was 9.8 cases per 100,000 native population but 40.8 cases per 100,000 immigrants [14].

Despite the restrictions and cutbacks applied, analysis of the data obtained in national health surveys in 2006 (pre-crisis) and 2011–2012 (mid-crisis) reveals no deterioration in immigrants’ access to healthcare or in their health status compared with individuals with Spanish nationality [15]. The 2011 survey was conducted prior to the adoption of RDL 16/2012. According to more recent data (the 2014 European Health Survey),Footnote 7 2.6 % of the Spanish population were unable to access medical care for financial reasons, and 2.4 % could not acquire prescription drugs. These percentages rose to 4.7 and 4.1 %, respectively, in the case of foreign residents.

Regarding the consumption of medicines, during the economic crisis the use of antidepressants increased by 35.2 %, although spending fell 38.7 % due to price reductions [16].

Spending cuts have lengthened waiting lists for healthcare. It is striking that, among the dozens of articles published on the effects of the recession on the health system and on public health in Spain, only a few have quantified or rigorously analysed its impact on waiting lists, which are consistently among the main complaints made by citizens, according to the health barometer.Footnote 8 Moreover, according to the Ministry of Health information system on waiting lists,Footnote 9 the number of patients in line for elective surgery in the public system increased by 43 % between June 2009 and June 2012, and the average waiting time increased by 21 %, from 63 to 76 days.

This situation varies among the Autonomous Communities, as a result of the diverse approaches taken to financial and policy restrictions, as discussed above. An ambitious step to minimise the harm done by extended waiting lists is the prioritisation of patients according to specific criteria, which has been launched in Catalonia for some processes [17].

In 2011, at the height of the crisis, Spain still compared well with other countries (such as Sweden, New Zealand, Ireland and Portugal) [18] as regards waiting lists for elective surgery for hip replacements and cataracts, although, in 2012, the waiting lists and times for cataract surgery, prostatectomy and hip replacements increased significantly, and the international comparison was much less favourable.

Although restrictions and spending cuts arising from the crisis were eventually eased, the indicators of waiting lists published in December 2015 were substantially worse in Spain than those for December 2014. Thus, nearly 550,000 patients were formally included in waiting lists, among an eligible population of 37.8 million; the average waiting time was 89 days, and 10.6 % of patients had to wait for over 6 months [19].

A secondary or indirect effect of the deteriorating conditions of access to public health services has been the increased reliance on private insurance plans.

3.1 Co-Payment

As of July 2012, RDL 16/2012 imposed a 10 % co-payment on the sales price of drugs prescribed to pensioners, as outpatients, by the public health service. These had previously been free of charge to pensioners. Moreover, non-pensioners (individuals in employment or unemployed) and earning over €18,000 per year were also required to pay a higher percentage (50–60 %, up from 40 %) of the sales price of drugs. Before the reform, all non-pensioners co-paid 40 %, with some personal exceptions for individuals with disabilities. Some medicines for treating chronic diseases had a reduced contribution of 10 % (instead of 40 %). The effects of these changes were immediately apparent, with a reduction in the consumption of outpatient prescription drugs [10]. In the first 14 months after the co-payment reform, the total number of prescriptions fell by more than 20 % in Catalonia, Valencia and Galicia, by more than 15 % in nine other regions, and by more than 10 % in 15 of the 17 Spanish regions. In Catalonia, the new co-payment came in addition to the co-payment of €1.00 per prescription that was charged until it was revoked by the Constitutional Court. That is the reason for the abrupt shift in the mean level of the time series.

However, after the initial period of adjustment, lasting 12–18 months, the effects of co-payment faded and prescriptions returned to the levels recorded before the regulatory change. The net outcome of this reform was a redistribution of the financial burden from the government to the individual, in the context of this specific item, prescription drugs, which presents low price elasticity of demand. Between 2009 and 2013, according to the Consumer Expenditure Survey conducted by the Spanish Institute of Statistics (INE), families’ out-of-pocket spending on medicines increased by 28.5 % in real terms. As expected, there were differences according to the type of drugs, with antidiabetics being less sensitive to price changes than anti-asthmatics [20]. The largest concern about the effects of co-payment is not so much consumption but health and fairness. The latter issue arises because no upper limit is set to the co-payment payable by non-pensioners (unlike pensioners) and so the cost of medication may represent a catastrophic level of spending for poor families. The other major concern is about the effects of co-payment in terms of health outcomes and whether these are comparable among different groups of patients. In other words, has the reform provoked horizontal inequities? An ongoing study of adherence to pharmacological treatments, based on microdata from a population-based cohort of patients in the Autonomous Community of Valencia discharged from hospital after a myocardial infarction, observed the existence of such inequities before RDL 16/2012, with low-income workers presenting lower levels of treatment adherence. Similarly, imposing co-payment on previously exempt pensioners reduced their likelihood of treatment adherence, although this effect faded over time, and disappeared after 12–18 months.

Drug co-payment in Spain only affects outpatient prescription and incorporates payment limits according to employment status and family income. However, in view of the increasingly regressive nature of the tax system, the healthcare service is playing a redistributive role as a result of the spending cuts applied, and this role has been reinforced with the new co-payment design. Thus, individuals aged 15–65 years and exempt from co-payment make more use of health services than the general population of the same age (in 2014, in Catalonia, 8.1 and 6 visits per year, respectively, to primary care centres; 10.9 and 3.1 %, respectively, attenders at mental health centres; 132.6 and 90.5 per thousand, respectively, standardised rate of hospitalisation). Such differences might arise because the health of these individuals is more precarious because of their disadvantaged socioeconomic status [14].

4 Reactions Among Economic Agents, and the Trend Toward Privatisation

The economic crisis, spending cutbacks and austerity policies have had a major impact on the expectations and decisions of all kinds of economic agents, including healthcare staff, the pharmaceutical industry and policy makers in this sector. Young doctors are refocusing their expectations, changing their preferences for specialities and seeking employment in areas that are more resistant to job loss and insecurity [21]. A collateral effect of the cuts and budgetary discipline applied to the public health system has been a progressive trend toward privatisation. The public sector has widespread experience of indirect management through arrangements such as public–private partnerships. During the crisis, attempts were made to extend this process in some Autonomous Communities, particularly in Madrid, seeking to achieve financial savings or at least to postpone payment deadlines. However, popular social movements, active both in the streets and in the courts, prevented the generalised adoption of market-oriented reforms. Nevertheless, the public sector coexists with a private sector that is predominantly profit motivated and increasingly outspoken, advocating a paradigm shift to increase its share in the national healthcare provision. During the worst years of the crisis, private health spending increased its share of the total. Premiums for voluntary private health insurance, taken out in parallel with public insurance and creating double coverage, have risen faster during these years of crisis than those for other branches of insurance. Thus, in Madrid, 27.9 % of citizens had private healthcare insurance in 2014, and the private sector share of total health spending rose from 25 % in 2009 to 28.29 % in 2013.

5 The Impact on Health Parameters

The most comprehensive study of the dynamics of 15 health indicators,Footnote 10 recorded before and after the onset of the economic recession (1995–2011), revealed no negative effects during the recession period (2008–2011) on rates of premature death from any cause except cancer [22]. Mortality from accidents and other causes even decreased, reversing the previous trend. Together with cancer mortality, the only indicator that presented a negative aspect was the incidence of HIV infections. In this respect, rigorous studies have not shown austerity policies to be causative.

Avoidable mortality is a more finely nuanced indicator than overall mortality because it includes only the causes that could have been addressed, within the healthcare system or externally. In Catalonia, this parameter presented the same downward trend as for overall mortality between 2007 and 2014 [14], although at a lower rate, and its incidence rose in some cases, such as lung cancer in women and suicides in men. However, preventable mortality from ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease presented very favourable trends, suggesting the cutbacks had no overall impact on population health. Nevertheless, the lack of an observed effect on mortality may be due to a delayed effect (i.e. poor health now may lead to increased mortality in the future).

Several empirical studies have been made of the dynamics of suicides and suicide attempts during the crisis, but the results obtained are inconclusive [23–27]. In any case, the selective increase in suicide attempts among males of working age, which has been reported in some studies, could be attributed more to the situation of the labour market and to high unemployment [25] than to austerity measures in the health system.

Neither does self-perceived health status appear to have deteriorated during the recession [22]. In fact, a comparison of the health surveys of 2006, 2011 and 2014, showed an improvement in the perception of health among most of the population, in contrast to other European countries where the economic crisis was less severe [28]. The 2014 SESPAS report also showed no negative impact on the incidence of infectious disease [29].

On the other hand, the impact of the crisis on mental health is well documented in a systematic review of seven studies carried out in Spain [30]. The numbers of patients with depression, and treated in primary care clinics during the recession, rose almost threefold compared with pre-crisis rates [31]. An observational retrospective study with population databases and 12-month follow-up concluded that the prevalence of major depression increased from 5.4 % in 2008–2009 to 8.1 % in 2010–2012 [16]. Depression worsened, especially among men of working age [32] and among workers [28], and has been associated with financial problems arising from the crisis [33]. This suggests that the causative factor is the labour market and unemployment; therefore, health policies would not appear to be responsible. In addition, the mental health of migrant workers in Spain was also found to have worsened during the economic crisis [34].

The impact of the recession has become immediately apparent among vulnerable population groups, and particularly in children [35]. In Catalonia, during the years of crisis, the social gradient of childhood obesity steepened, and there were greater inequalities in health-related quality of life [36]. The long-term consequences of this deprivation affecting children today are expected to be very significant in the future [37]. Consequently, many scientists are calling for prompt intervention by public authorities in sectors such as education to ensure children receive adequate nutrition.

6 Has the Economic Crisis Reduced Fairness in the Healthcare System?

The recession has resulted in increased economic inequality according to the Gini index.Footnote 11 Some health problems, such as major depression, have a clear social gradient, and this appears to have steepened during the crisis [32]. The social gradient in obesity also persisted or worsened from 2006 until 2014. It has been observed that, in recessive periods, health inequalities due to inadequate education increase, but those related to individual professional status and household living conditions are attenuated [38].

Spending cuts, and their consequences in terms of extended waiting lists, have impeded access to health services, and this ultimately results in medical needs being unmet. Patients in this situation tend to be concentrated among the lower-income quintiles, and their number increased during the crisis (2011–2013), especially among the population in the first two quintiles [39].

According to an analysis of successive surveys of Spanish health, from 2003 to 2011, “the crisis effects on health emerge especially in the case of our more preventable illnesses and among lower educated groups”. This educational gradient was observed for myocardial infarction, diabetes, depression and cancer [40]. Another study analysed surveys from 2001 to 2011 and concluded that “socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behaviour have intensified in the period 2011/12, especially regarding diet” [41]. Nevertheless, the overall conclusion reached is that “results about the impacts of the economic recession on health equity are inconsistent, due to the diversity of time periods used in the analyses, the heterogeneity of socioeconomic and health variables considered, the changes in the socioeconomic profile of the groups under comparison in times of crises, and the type of measures used to analyse the magnitude of social inequalities in health” [42].

An analysis of monthly mortality series by age and sex of individuals aged ≥60 years, from 1995 to the end of 2012, concluded that “the observed mortality seems to be decreasing at a slower rate than what would have been expected in the absence of the crisis; there has been an increase in winter mortality; and the impact of the crisis has been greater for female than for male mortality” [43]. The economic conditions imposed by the crisis, would thus particularly affect vulnerable population groups such as the elderly and the very young.

The crisis has had a deterrent effect on healthcare use by disadvantaged social classes lacking access to public health services, with dental attention suffering particularly in this respect [39].

7 Discussion

The anti-crisis measures adopted do not form a compact, strategically defined whole, but rather a succession of measures, at both regional and national levels, of varying degrees of severity, that have in common the aim of limiting or controlling increases in public health spending [44]. However, no attempt has been made, in response to the crisis (and notwithstanding the literal meaning of the expression “anti-crisis” measure), to reform the health system with a view to achieving its long-term sustainability [9, 45]. Among other issues remaining to be addressed, the Spanish public healthcare system has yet to wholeheartedly embrace a culture of evaluation and prioritisation [46], to clarify the role of the private sector in healthcare and to implement appropriate incentives that align the needs and ambitions of different stakeholders. Furthermore, foundations were laid during the crisis for the ring-fencing of certain decisions (e.g. allocating specific funds for specific medications, such as direct antivirals to treat hepatitis C), thus opening the door for the future segregation of decisions, and representing a backward step in prioritisation.

As shown above, although some negative health outcomes can be characterised empirically, they are not always attributable to any specific cause. For example, it cannot be determined whether the increase in suicides among men of working age in Catalonia is due to health spending cutbacks, to restrictive measures in other areas of social policy, to the bank and mortgage crisis, to the general economic situation or to the markets.

Much of the research on the crisis and its impact on health has been conducted in studies using cross-sectional data, and this seriously limits the inferences that can be drawn regarding causality. Another difficulty is to deal with the lags between the cause (economic recession) and its effects (mortality, morbidity). To better estimate the effects of the crisis on health with microdata, it would be useful to have population data of cohorts from clinical records and registries and to use models for longitudinal data. Moreover, the debate has a highly ideological component. As regards the cause-and-effect nature of the recession and public health policies, many theorists in the medical field have laid the responsibility on austerity policies, by action or omission, but have often ignored the opportunity cost of public spending on health and social policies. As a proximal cause, the loss of housing has been associated with “a much poorer health status than the general population, even when compared to those belonging to the most deprived social classes” [47], but health policies alone can do little to alleviate this problem.

Unlike other Mediterranean countries, and Greece in particular, where the economic crisis has had devastating effects on the health of citizens and has provoked drastic cuts in health spending [48–50], the public health system in Spain has not fared so badly. Although this sector has borne a disproportionate share of the burden of spending cuts provoked by the crisis, in relation to other benefits provided by the welfare state, it has managed to avoid (more so in some Autonomous Communities than in others) the irreversible deterioration of public healthcare, thanks to the dedication of healthcare personnel and to good management. Strategies for the integration of healthcare attention, at all levels, strategies for chronic care and risk-sharing contracts with the pharmaceutical industry are examples of advances in management and organisation that have been developed in some regions of Spain during the crisis, but not necessarily due to the crisis.

The most tangible consequences of healthcare spending cuts and austerity measures concern problems of access to healthcare, both for specific population groups (undocumented immigrants) and for patients in general, who for some services must suffer waiting lists that are considerably longer than those encountered prior to the crisis. This loss of access is a very sensitive issue, as reflected in the health barometer, and has stimulated a boom in private insurance, resulting in complementary and/or double coverage. Healthcare management has marginally improved, but no major system reforms aimed at long-term sustainability have been carried out.

Notes

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE. Contabilidad Nacional Trimestral de España base 2000. http://www.ine.es/dyngs/IOE/es/operacion.htm?numinv=30024.

The list of indicators includes premature mortality by 13 causes (all causes; cancer; cardiovascular disease; respiratory disease; digestive disease; genitourinary disease; HIV disease; rest of infectious diseases; road traffic injury; rest of unintentional injuries; illicit drug-induced death; suicide; homicide), prevalence of poor perceived health and HIV incidence.

References

Cortès-Franch I, López-Valcárcel BG. Crisis económico-financiera y salud en España. Evidencia y perspectivas. Informe SESPAS 2014. Gaceta Sanitaria. 2014;28:1–6.

Budhdeo S, Watkins J, Atun R, Williams C, Zeltner T, Maruthappu M. Changes in government spending on healthcare and population mortality in the European Union, 1995–2010: a cross-sectional ecological study. J Royal Soc Med. 2015. doi:10.1177/0141076815600907.

Karanikolos M, Mladovsky P, Cylus J, Thomson S, Basu S, Stuckler D, et al. Financial crisis, austerity, and health in Europe. Lancet. 2013;381(9874):1323–31.

Legido-Quigley H, Otero L, la Parra D, Alvarez-Dardet C, Martin-Moreno JM, McKee M. Will austerity cuts dismantle the Spanish healthcare system? BMJ. 2013;346. doi:10.3390/ijerph111010182.

Cervero-Liceras F, McKee M, Legido-Quigley H. The effects of the financial crisis and austerity measures on the Spanish health care system: a qualitative analysis of health professionals’ perceptions in the region of Valencia. Health Policy. 2015;119(1):100–6.

Andreu-Segura B. Recortes, austeridad y salud. Informe SESPAS 2014. Gaceta Sanitaria. 2014;28(Suppl 1):7–11. doi:10.1016/j.gaceta.2014.02.009.

Morrison J, Pons-Vigués M, Bécares L, Burström B, Gandarillas A, Domínguez-Berjón F, et al. Health inequalities in European cities: perceptions and beliefs among local policymakers. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e004454.

Ministerio de Hacieda y Administraciones Públicas. Avance de la actuación económica y financiaera de las Administraciones Públicas. Madrid. 2013. http://www.igae.pap.minhap.gob.es/sitios/igae/es-ES/ContabilidadNacional/infadmPublicas/Documents/InformesAnuales/Avance_AAPP_2013.pdf.

Casasnovas GL, López-Valcárcel BG. El sistema sanitario en España, entre lo que no acaba de morir y lo que no termina de nacer. Papeles de Economía Española. 2016;147:190–211. https://www.funcas.es/Publicaciones/Detalle.aspx?IdArt=22268.

Puig-Junoy J, Rodríguez-Feijoó S, Lopez-Valcarcel BG. Paying for formerly free medicines in Spain after 1 year of co-payment: changes in the number of dispensed prescriptions. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2014;12(3):279–87.

Giovanella L, Stegmüller K. The financial crisis and health care systems in Europe: universal care under threat? Trends in health sector reforms in Germany, the United Kingdom, and Spain. Cuadernos de Salud Pública. 2014;30(11):2263–81.

Oyagüez I, Frías C, Seguí MA, Gómez-Barrera M, Casado MA, Queralt Gorgas M. Eficiencia de tratamientos oncológicos para tumores sólidos en España. Farmacia Hospitalaria. 2013;37(3):240–59.

Legido-Quigley H, Urdaneta E, Gonzalez A, La Parra D, Muntaner C, Alvarez-Dardet C, et al. Erosion of universal health coverage in Spain. Lancet. 2013;382(9909):1977.

GENCAT. Observatory del Sistema de Salut de Catalunya. Efectes de la crisi econòmica en la salut de la població de Catalunya. 2016. http://observatorisalut.gencat.cat/es/observatori-sobre-els-efectes-de-crisi-en-salut/detall/informe/inici/.

Garcia-Subirats I, Vargas I, Sanz-Barbero B, Malmusi D, Ronda E, Ballesta M, et al. Changes in access to health services of the immigrant and native-born population in Spain in the context of economic crisis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(10):10182–201.

Sicras-Mainar A, Navarro-Artieda R. Use of antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder in primary care during a period of economic crisis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:29.

Solans-Domènech M, Adam P, Tebé C, Espallargues M. Developing a universal tool for the prioritization of patients waiting for elective surgery. Health Policy. 2013;113(1):118–26.

Siciliani L, Moran V, Borowitz M. Measuring and comparing health care waiting times in OECD countries. Health Policy. 2014;118(3):292–303.

Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Sistema de Informacion de Listas de Espera a diciembre 2015. 2016. http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/inforRecopilaciones/docs/LISTAS_PUBLICACION_DIC15.pdf.

Puig-Junoy J, Rodriguez-Feijoó S, González López Valcárcel B, Gómez-Navarro V. Impacto de la reforma del copago farmacéutico sobre la utilización de medicamentos antidiabéticos, antitrombóticos y para la obstrucción crónica del flujo aéreo. Revista Española de Salud Pública. 2016;90(29). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=27125567.

Harris JE, Gonzalez Lopez-Valcarcel B, Ortun V, Barber P. Specialty choice in times of economic crisis: a cross-sectional survey of Spanish medical students. BMJ Open. 2013;3(2). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002051.

Regidor E, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, de la Fuente L. Has health in Spain been declining since the economic crisis? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(3):280–2.

Bernal JAL, Gasparrini A, Artundo CM, McKee M. The effect of the late 2000s financial crisis on suicides in Spain: an interrupted time-series analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2013. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckt083.

Librero J, Segura A, Lopez-Valcarcel BG. Suicides, hurricanes and economic crisis. Eur J Public Health. 2013. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckt167.

Córdoba-Doña JA, San Sebastián M, Escolar-Pujolar A, Martínez-Faure JE, Gustafsson PE. Economic crisis and suicidal behaviour: the role of unemployment, sex and age in Andalusia, southern Spain. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13:55. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-13-55.

Miret M, Caballero FF, Huerta-Ramírez R, Moneta MV, Olaya B, Chatterji S, et al. Factors associated with suicidal ideation and attempts in Spain for different age groups. Prevalence before and after the onset of the economic crisis. J Affect Disord. 2014;163:1–9.

Saurina C, Marzo M, Saez M. Inequalities in suicide mortality rates and the economic recession in the municipalities of Catalonia, Spain. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12939-015-0192-9.

Bacigalupe A, Esnaola S, Martín U. The impact of the Great Recession on mental health and its inequalities: the case of a Southern European region, 1997–2013. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):1. doi:10.1136/jech-2014-204602.

Llácer A, Fernández-Cuenca R, Martínez-Navarro F. Crisis económica y patología infecciosa. Informe SESPAS 2014. Gaceta Sanitaria. 2014;28(Suppl. 1):97–103.

Frasquilho D, Matos MG, Salonna F, Guerreiro D, Storti CC, Gaspar T, et al. Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2720-y.

Gili M, Roca M, Basu S, McKee M, Stuckler D. The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(1):103–8.

Bartoll X, Palència L, Malmusi D, Suhrcke M, Borrell C. The evolution of mental health in Spain during the economic crisis. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(3):415–8.

Córdoba-Doña JA, Escolar-Pujolar A, San Sebastián M, Gustafsson PE. How are the employed and unemployed affected by the economic crisis in Spain? Educational inequalities, life conditions and mental health in a context of high unemployment. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2934-z.

Agudelo-Suárez AA, Ronda E, Vázquez-Navarrete ML, García AM, Martínez JM, Benavides FG. Impact of economic crisis on mental health of migrant workers: what happened with migrants who came to Spain to work? Int J Public Health. 2013;58(4):627–31.

Rajmil L, Siddiqi A, Taylor-Robinson D, Spencer N. Understanding the impact of the economic crisis on child health: the case of Spain. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s12939-015-0236-1.

Rajmil L, Medina-Bustos A, de Sanmamed MJF, Mompart A. Impact of the economic crisis on children’s health in Catalonia: a before-after approach. BMJ Open. 2013;3(8):e003286. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003286.

Flores M, García-Gómez P, Zunzunegui M-V. Crisis económica, pobreza e infancia.¿ Qué podemos esperar en el corto y largo plazo para los “niños y niñas de la crisis”? Informe SESPAS 2014. Gaceta Sanitaria. 2014;28:132–6.

Barroso C, Abásolo I, Cáceres JJ. Health inequalities by socioeconomic characteristics in Spain: the economic crisis effect. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):1. doi:10.1186/s12939-016-0346-4.

Urbanos Garrido R, Puig-Junoy J. Políticas de austeridad y cambios en las pautas de uso de los servicios sanitarios. Informe SESPAS 2014. Gaceta Sanitaria. 2014;28(Suppl 1):81–8.

Zapata Moya A, Buffel V, Navarro Yáñez C, Bracke P. Social inequality in morbidity, framed within the current economic crisis in Spain. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):131.

Bartoll X, Toffolutti V, Malmusi D, Palència L, Borrell C, Suhrcke M. Health and health behaviours before and during the Great Recession, overall and by socioeconomic status, using data from four repeated cross-sectional health surveys in Spain (2001–2012). BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2204-5.

Bacigalupe A, Escolar-Pujolar A. The impact of economic crises on social inequalities in health: what we know so far. Int J Equity Health. 2014;25:13–52. http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/13/1/52.

Benmarhnia T, Zunzunegui MV, Llácer A, Béland F. Impact of the economic crisis on the health of older persons in Spain: research clues based on an analysis of mortality. SESPAS report 2014. Gaceta Sanitaria. 2014;28(Suppl 1):137–41. doi:10.1016/j.gaceta.2014.02.016.

Gallo P, Gené-Badia J. Cuts drive health system reforms in Spain. Health Policy. 2013;113(1):1–7.

Gené-Badia J, Gallo P, Hernández-Quevedo C, García-Armesto S. Spanish health care cuts: penny wise and pound foolish? Health Policy. 2012;106(1):23–8.

González López Valcárcel B, Ortún V. Pals don’t evaluate pals … : or do they? Revista Española de Salud Pública. 2015;89(2):119–23.

Novoa AM, Ward J, Malmusi D, Díaz F, Darnell M, Trilla C, et al. How substandard dwellings and housing affordability problems are associated with poor health in a vulnerable population during the economic recession of the late 2000s. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12939-015-0238-z.

Kentikelenis A, Karanikolos M, Papanicolas I, Basu S, McKee M, Stuckler D. Health effects of financial crisis: omens of a Greek tragedy. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1457–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61556-0.

Simou E, Koutsogeorgou E. Effects of the economic crisis on health and healthcare in Greece in the literature from 2009 to 2013: a systematic review. Health Policy. 2014;115(2):111–9. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.02.002.

Kentikelenis A, Karanikolos M, Reeves A, McKee M, Stuckler D. Greece’s health crisis: from austerity to denialism. Lancet. 2014;383(9918):748–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62291-6.

Acknowledgments

This paper forms part of the research funded by Grant ECO2013-48217-C2-1 under the “National Programme for Research, Development and Innovation to Address the Challenges of Society: National Plan for Scientific Research and Technical Innovation 2013–2016” funded by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain (http://invesfeps.ulpgc.es/en). The funder had no influence on the conduct of this study or on the drafting of this manuscript.

Author contributions

Both authors reviewed the literature on the topic and contributed to the design and writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Beatriz Gonzalez Lopez-Valcarcel and Patricia Barber do not have any relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lopez-Valcarcel, B.G., Barber, P. Economic Crisis, Austerity Policies, Health and Fairness: Lessons Learned in Spain. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 15, 13–21 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-016-0263-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-016-0263-0