Abstract

Background

The Central Statistics Office released new figures on Ireland’s health spending in December 2015, based on the System of Health Accounts (SHA2011). These figures differ from previous figures, by virtue of an expanded definition of what constitutes health care. The new figures also provide more detail on health expenditure than the previous figures allowed.

Aims

This article examines the new figures, drawing out findings of note and discussing the implications of these for the Irish health care system. It also compares Ireland with international health systems, highlighting where Ireland is unusual or comparable to international norms.

Findings

Healthcare spending in Ireland as a percentage of GDP is higher than in many other countries, having increased during the economic downturn, although this was due more to the contraction in GDP than an increase in spending. While the majority of healthcare expenditure in Ireland comes from the Government, the share of private expenditure on healthcare in Ireland has increased, with implications for equity in the system. Over half of the expenditure is on curative and rehabilitative services, broadly in line with other countries. The proportion of spending going to long-term care facilities is relatively high by international standards.

Conclusion

Suggestions that Ireland is over-spending on health need to be tempered by cognisance that the Irish health system is under-resourced in a number of areas (particularly the number of doctors and the number of hospital beds) and has not fully recovered from cutbacks in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In December 2015, the Central Statistics Office (CSO) released a new set of health accounts for Ireland [1], based on the System of Health Accounts (SHA) 2011. A further release, containing revised figures for 2013 as well as figures for 2014, was released in June 2016Footnote 1 [2]. These figures involve a revised approach to measuring spending on healthcare in Ireland, which brings the Irish figures into line with most other OECD countries. They predominantly relate to current healthcare spending, providing a more detailed breakdown of this spending—by functions of healthcare, by healthcare providers and by financing schemes—than was previously available.

The System of Health Accounts, which was devised by the OECD and is used by the OECD, Eurostat (the European statistical agency) and the World Health Organisation, “contains common concepts, definitions, classifications and accounting rules to enable comparability over time and across countries. It provides a basis for uniform reporting by countries with a wide range of different models of organising their national health systems.” [1, p. 8] It also uses a common definition of healthcare, as distinct from related social care services, which facilitates more direct comparisons between international health systems, given the diversity in the design of these systems and their interaction/boundaries with social care services.

The accounts are used to examine where the money comes from to finance the health care system (financing schemes); who the money goes to (providers of healthcare goods and services); and what kind of goods/services are purchased/performed (the functions of healthcare).

The incorporation of a revised methodology in these accounts has had implications for comparisons of current healthcare spending in Ireland with that in other countries. In particular, they show a higher level of health spending in Ireland than was previously estimated [3]. They have also resulted in revisions to the aggregate level data for previous years (from 2000 to 2012), although the CSO has stressed that the data sources and methods used for the revisions are different from those used for the new figures (which relate to 2013 onwards), and therefore, there is a break in the series between 2012 and 2013 [1].

This paper examines the new figures, both at an aggregate level and at a more detailed level, and presents some of the salient points that arise. It also assesses what the new figures tell about the Irish healthcare system and considers the implications for health policy in Ireland. Some comparisons are also made with international figures, highlighting where Ireland is above, below or in line with the average.

The system of health accounts

The figures released in December 2015 and subsequently are based on the international System of Health Accounts 2011 (SHA2011), devised by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and used for joint reporting of healthcare expenditure by the OECD, Eurostat and the World Health Organization (WHO). The figures break current health expenditure down by functions of healthcare, healthcare providers and financing schemes. Previous figures, categorised under the SHA1.0 system, were only available at a more aggregated level.

Detailed figures are not available for capital expenditure, although some high-level figures are included. Capital expenditure accounted for an average of 5 % of total health expenditure between 2000 and 2014 [2], so current expenditure is the dominant form, which explains the focus on the latter. However, capital expenditure is not unimportant in an Irish context, particularly given significant under-investment in the Irish health system in the late 1980s and early 1990s, which led to a significant reduction in the number of hospital beds in particular, from which the Irish health system has not fully recovered.

The main difference between the current SHA-based health accounts and those previously available—via the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) or World Health Organization (WHO)—is in the definition of what constitutes health spending. In particular, the SHA-based figures include a larger proportion of long-term and disability care than the previous set of figures. Previously, many of the services in these sectors were considered social care services rather than health services and were, therefore, excluded from earlier estimates of health spending. The SHA distinguishes between long-term care services with a health purpose and those with a social purpose—for example, social care services such as assistance services that enable a person to live independently in their own home are not included—although it acknowledges that it may be difficult to separate them as they are often delivered within a single package of care [4].

It should be noted that the estimates released in December 2015 were the first such estimates using the SHA methodology, and the CSO acknowledged that the figures were preliminary and will be subject to revision (some minor revisions were contained in the June 2016 release). It also noted that it was difficult in some cases to separate health care and social care, as they are often delivered in the same package of services, and that this “has resulted in the amount of health care being somewhat over-stated in some areas.” [1, p. 9; 2, p. 13] Furthermore, comparisons with the OECD average may also be revised, as Ireland is not the only country moving to the SHA basis of calculation—for example, the OECD notes that “an ongoing review of Japanese long-term care boundaries concerning SHA will likely lead to a significant increase in health spending based on SHA2011 to be released in 2016.” [3, p. 168]. However, it is unlikely that the OECD average will change significantly.

An analysis of healthcare spending in Ireland

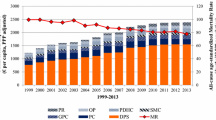

The headline figures in the CSO releases are that Ireland’s current health expenditure in 2013 was €18.8bn, rising to €19.1bn in 2014 (albeit that the 2014 figures are first estimates). This represents 10.5 % of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2013 and 10.1 % in 2014, or 12.3 and 11.7 %, respectively, of Gross National Income (GNI).Footnote 2 Previous estimates had put health spending in 2012 at 8.1 % of GDP [3], however, this has now been revised upwards to 10.1 % of GDP [2]. These figures compare with an OECD average of 8.9 % of GDP in 2012 and 9.0 % in 2013 (see Table 1; Fig. 1).Footnote 3

Therefore, having previously been estimated at below-average health spending relative to the OECD average, the new methodology has led to an estimate that is above the average (see Fig. 1). A figure of 10.5 % of GDP in 2013 would put Ireland in eighth place in the OECD, slightly ahead of Belgium (10.4 %) and Denmark (10.3 %), although still considerably lower than the US (16.4 %), as well as below Japan and five other European countries: Switzerland, Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany and France (see Table 2). If spending as a percentage of GNI is used, which some argue would be a fairer comparator given the difference between GNI and GDP in Ireland, then Ireland’s health spending would be even higher, coming in second only to the US.Footnote 4 However, it has been pointed out that Ireland’s spending as a percentage of GDP was approximately equal to the Small Open Economy (SOE) median in 2013 [6].

However, one thing that needs to be borne in mind is that spending as a percentage of GDP (or GNI) is influenced by both health spending and the level of GDP (or GNI). In this context, it is worth noting that both measures of economic activity peaked in 2007, fell until 2010 and began to rise again in 2011. The spending figures as a percentage of GDP remained below the OECD average until 2007 and only began to exceed the OECD average from 2008 onwards, peaking in 2010, shortly after the economy reached its local nadir [2]. While current health spending rose between 2007 and 2009, it then broadly flattened until 2012, before rising again in 2013 (see Table 1). Hence, much of the increase in spending as a proportion of GDP was influenced by the contraction of the economy rather than by a significant increase in health spending.Footnote 5

The Irish case is in contrast to other countries that experienced severe financial consequences as a result of the economic downturn. While current expenditure on health in Ireland rose by 5.3 % between 2009 and 2013, current health expenditure over the same period fell by 4.3 % in Spain, 10.7 percent in Portugal and 31.9 % in Greece [7], although data issues in the latter country mean that these figures come with a health warning.

Another trend that is evident from the figures is that, while current public health expenditure has remained broadly stable from 2008 to 2014, current private expenditure increased by 66 % over the same period. It is clear, therefore, that a larger share of healthcare expenditure is now being borne by private sources (nearly 31 % in 2014, compared with less than 21 % in 2008), with a consequent decrease in the share coming from public sources. In monetary terms, this represents an increase in private spending from €3.5bn in 2008 to almost €5.9bn in 2014 (see Table 1).Footnote 6

The proportion of current health spending coming from private sources in Ireland is significantly higher than the EU-15 and SOE median values and was exceeded only by two countries in the EU-15, Portugal and Greece [6]. Private expenditure accounted for 33.8 and 39.1 %, respectively, of current health expenditure in the latter two countries, while the proportion in Spain, at 30.2 %, was only slightly below that in Ireland. While the proportion of expenditure accounted for by private sources was relatively stable between 2008 and 2014 in Greece and Portugal, it increased from 26.4 to 30.2 % in Spain, a similar pattern to that seen in Ireland, although the increase was not as pronounced [7].

Private health care expenditure comes from two sources—voluntary health care payments (mostly related to voluntary health insurance) and out-of-pocket payments by households—with these two sources accounting for a broadly equal proportion of total private spending in 2014 [2].

Figures from The Health Insurance Authority—the health insurance industry regulator—show that premium income rose from €1.561bn in 2008 to €2.316bn in 2014, while claims paid increased from €1.154bn in 2007 to €1.81bn in 2014 (no figure is available for the total amount of claims paid in 2008) [8]. This was despite a fall in the number of people with insurance, from 2.297 million in December 2008 to 2.017 in June 2014. However, between 2008 and 2014, the health insurance component of the Consumer Price Index showed an increase of over 120 %, reflecting significant premium increases. These increases were driven by a number of factors, including rising charges for the use of private beds in public hospitals, greater volume of treatments and advances in medical technology [9]. A fall in the proportion of the market in younger age groups also meant a higher concentration of older members, who have higher average claim costs, while Government policy to charge insurers for the use of any beds in public hospitals from 1 January 2014 also led to an increase in the amount of money paid by insurers for public hospital accommodation [10].

While the number of people qualifying for medical cards increased during the economic downturn, those who were required to pay out-of-pocket payments for medical treatment faced a number of increases in these out-of-pocket payments over the 2008–2014 period. During that time, the Drug Payment Scheme threshold, above which people are reimbursed for prescription drug spending, rose from €90 per month to €144 per month. The charge for visiting an Accident and Emergency department without a GP referral rose from €66 to €100, while the statutory charge for inpatient accommodation in a public hospital, payable by public patients who do not hold a medical card, increased from €66 per night (up to a maximum of €660 in a continuous 12-month period) to €75 per night (up to a maximum of €750 in a continuous 12-month period). Even those with medical cards were not immune, with the introduction of the prescription charge in 2010 (initially 50c per prescription item up to a maximum of €10 per household per month) and subsequent increases (to €2.50 per prescription item up to a maximum of €25 per household per month in 2014).

The increase in the share of expenditure being raised from private sources has implications for the fairness of the health system, as health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket payments are both regressive funding mechanisms, compared with taxation, which is a progressive funding mechanism and provides the vast majority of public expenditure.

In this context, regressive means that households (or individuals) with lower incomes pay a higher proportion of their incomes towards health care than households (or individuals) with higher incomes. A typical example of an out-of-pocket payment would be a flat fee for visiting a General Practitioner, which in Ireland is estimated to average €52.50 [11], which would represent a higher proportion of income for a household with a weekly income of €500 than it would for a household with a weekly income of €5000, for example. Private health insurance premiums in Ireland are community rated, meaning that, subject to some exceptions for children, young adults and members of group schemes, all subscribers to a given plan are charged the same premium as all other subscribers to that plan, irrespective of income. Hence, for members on the same plan, the premiums would represent a higher proportion of income for a low-income member than for a high-income member.

The new figures also present more detail than was previously available about the spending directed towards different providers of health care services. The bulk of the expenditure in 2014 happened in hospitals (35 %), ambulatory health care providers (predominantly GPs and dentists) (20 %), long-term residential facilities (19 %) and retailers of medical goods (predominantly pharmacies) (14 %). The proportion of spending in hospitals is broadly in line with international comparisons, while the proportion spent on ambulatory health care providers is slightly below a number of other European countries (where, typically, between 20 and 30 % of healthcare expenditure is spent on such providers, although this share is lower in some countries, such as the Netherlands at 17 %). By contrast, Ireland has the second highest share of expenditure on long-term residential facilities, with only the Netherlands (at 26 %) coming in higher, while a number of European countries spend less than 10 % of the healthcare expenditure on such providers. Ireland is mid-table in terms of the proportion of spending in retailers of medical goods [2, 7].

The main functions on which money was spent in 2014 were curative and rehabilitative care (54 %, broadly in line with international norms), long-term care (22 %, towards the higher end of the scale) and medical goods (15 %, roughly mid-table) [2, 7]. Three percent of current health care expenditure in 2014 was on preventive careFootnote 7 (the same proportion as in 2013) [2].

The initial estimates suggested that only 1 % of current health care expenditure was spent on preventive care, which was a relatively low proportion, approximately half the EU-15 average and also significantly below the SOE median [6]. However, the revised figures of 3 % are more in line with international comparators, although there is considerable variation in the proportion of health expenditure spent on preventive care, ranging from less than 2 % in France, Greece, Portugal and the Slovak Republic to over 4 % in Italy and the UK and over 6 % in Canada. Other countries spending a similar proportion to Ireland include Hungary, Norway and Poland [7].

In absolute terms, in 2014, spending on preventive care in Ireland equated to €113.80 per capita, similar to that in Finland (€118.70) and significantly ahead of countries like France (€69.60) and Belgium (€78.90), but below that of Germany (€126.40) and the Netherlands (€157.90) [7]. Research has found that spending on preventive care is cost-effective in that the reduction in the cost of curative care (arising from the reduction in the need for such care) is greater than the cost of preventive care [see, for example, 12].

By contrast, Ireland spends significantly more than the EU-15 and SOE median values on day curative and rehabilitative care (the excess being around €900 m to €1.1bn) [6]. In keeping with previous findings [3], spending on pharmaceuticals and other medical non-durables was significantly above average [6].

The source of spending on different functions also reveals distinct trends. For example, just over two-thirds of the money spent on curative and rehabilitative services came from the government, with a further 17 % coming from voluntary health insurance payments. The proportion of spending on this health care function coming from government (or compulsory financing schemes such as social health insurance) is higher in most European countries. By contrast, almost 80 % of funding for long-term care services came from the government (mid-table in an international context), with almost all of the remainder coming from out-of-pocket payments. Out-of-pocket payments accounted for over 30 % of pharmaceutical expenditure, an above average proportion compared with other countries, with the remainder paid for by the government [2, 7].

Overall, the government provided most of the funding of health care providers, at 69 % in 2014 (down slightly from almost 70 % in 2013). This included three-quarters of spending in long-term care facilities and 70 % of hospital expenditure. Nearly 40 % of out-of-pocket payments were spent on ambulatory health care providers (an above average proportion by international standards, possibly reflecting the relatively high out-of-pocket payments required to see GPs for those without medical cards or GP Visit cards), with a further 20 % spent in pharmacies [2].

A sizeable majority—just over 72 %—of voluntary health insurance payments were spent on hospital services. However, interestingly, the figures show a slight decrease between 2013 and 2014 in the amount spent on hospitals by voluntary health insurance schemes [2], despite the introduction of charges for insured patients in all public hospital beds from 1st January 2014, which led to an increase in the amount paid to the HSE in private hospital charges between 2013 and 2014 [10]. This may suggest that the introduction of these charges displaced hospital spending by insurers in private hospitals.

Implications for the Irish health system

The new SHA figures suggest that Ireland’s health spending is higher than had previously been thought, albeit this is down to a change in the definition of what constitutes health services rather than an increase in spending per se. A resultant effect is that Ireland’s health spending now ranks higher compared with other countries. It has been suggested that, in light of this, more should be expected of the system. In particular, the Irish system has been criticised for requiring a high proportion of people (approximately 60 %) to pay significant out-of-pocket payments for primary care services, and for long waiting lists for public hospital services [13].

Notwithstanding the indication of higher than average spending as a percentage of economic activity in the recent figures, it remains the case that Ireland’s health system was under-funded during the 1980s and 1990s [14], and the implications of this are still being felt. For example, the number of acute hospitals beds now is still approximately one-sixth lower than it was in 1980, despite an increase in the population of around one-third and an increase in the over-65 population of around two-thirds over the same period [14–16].

International figures show that Ireland has 2.8 hospital beds per 1000 population, compared with an OECD average of 4.8 per 1000 population [3]. The figures also show a below-average number of doctors (2.7 per 1000 population, compared with an OECD average of 3.3) and particularly a shortage of specialists [3]. To bring these figures into line with the OECD average (based on a population of just over 4.7 million) would require around 2800 additional doctors and over 9000 additional hospital beds.

Ireland is also unusual internationally in not having universal coverage for primary care services, and has an unusually high out-of-pocket charge for GP services for those not covered by medical cards or GP Visit cards [13]. These facts demonstrate that the criticism of Ireland’s two-tier health system, which focuses on the preferential treatment given to private patients in terms of hospital care, does not fully capture the nuances of the system.

At primary care level, those who would be considered public patients (those with medical cards or GP visit cards) are better off, as they do not face a direct financial barrier to accessing GP services. In this regard, it is worth noting that evidence suggests that over a quarter of those without medical cards put off visiting a GP on cost grounds, compared with less than 5 % of those with medical cards [17]. This may go some way to explaining why the SHA figures show that only 38 % of expenditure in medical practices came from out-of-pocket payments, despite the fact that approximately 60 % of people have to pay out-of-pocket for GP services [2].Footnote 8

Discussion and conclusions

The new SHA figures suggest that health spending as a percentage of GDP in Ireland is above the OECD average, compared with previous figures that suggested the opposite. The difference lies primarily in the definition of what constitutes a health service, with a higher proportion of long-term and disability care now being included in this definition.

However, care should be taken in interpreting the figures, as health spending as a proportion of economic activity can be influenced by either factor, and in Ireland’s case a dramatic fall in economic activity during the recent economic crisis played a pivotal role in increasing Ireland’s health spending as a proportion of economic activity. In this context, it is interesting to note that there was a lag between the downturn in economic activity in Ireland (which peaked in 2007) and that in health spending (which peaked in 2009).

Furthermore, the increase in health spending was almost entirely driven by a rise in private spending, while public spending remained broadly static. Therefore, the burden of payment has shifted, with implications for the progressivity of the system. One of the main factors influencing the take-up of private health insurance is a perception that public healthcare services are inadequate, while another is a perception of a lack of access to such services [19]. In this context, the widely publicised cuts in the HSE budget during the years of the downturn may have influenced some people to take out, or maintain, private health insurance. Although private health insurance take-up fell from a peak of almost 2.3 million people at the end of 2008 to just over 2 million in mid-2014 (it has since risen, largely as a result of the introduction of lifetime community rating in May 2015), the contraction of 12 % in take-up in the face of an increase of 127 % in like-for-like premiums over the same period, along with a contraction in employment and outward migration, suggests considerable resilience on the part of those who hold it.

The increase in the proportion of healthcare expenditure coming from private sources also has implications for equity in the system. It has previously been noted that the public–private mix of funding and delivery in Ireland leads to a number of cross-subsidies within the system, some of which favour those on lower incomes but others of which favour those on higher incomes [20]. In setting out the role of the recently established Oireachtas Committee on the Future of Healthcare, which is tasked with formulating a 10-year plan for the Irish health system, the Oireachtas noted “the need to establish a universal single tier service where patients are treated on the basis of health need rather than ability to pay.”Footnote 9 The Committee will need to reverse the recent increase in private payments to move towards the fulfilment of this particular objective.

In terms of the outcomes of the Irish health system, it is clear—notwithstanding the higher spending contained in the SHA figures compared with the previous figures—that to improve access for public patients to hospitals and to reduce or remove the financial barrier to private patients for accessing GP services, significant public investment will be required in the Irish health system.

This will be required, among other things, to address a shortage of doctors and hospital beds, to increase the amount of public patients being treated in public hospitals, and to reduce the out-of-pocket cost of visiting GPs. Some of this may be offset by reductions in private spending—on private health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket payments—but it is likely that an increase in overall spending will result.

However, it should also be noted that some outcomes in the Irish health system are reasonably good. In particular, life expectancy at birth in Ireland, at 81.1 years, is higher than the OECD average of 80.5 years [3]. The mortality rate from ischemic heart disease in Ireland, while still above the OECD average (136 deaths per 100,000 population versus an average of 117), has reduced at a faster rate (down 59 % between 1990 and 2013, compared with an OECD average decline of 45 %) [3]. Meanwhile, perceived states of health in Ireland are among the highest in the OECD, with 82 % reporting their health as good or very good, the fifth highest proportion out of 33 countries in the survey [3].

Furthermore, although Ireland is ranked mid-table in comparisons of European health systems (having lost a number of places as a result of the discontinuation by the survey co-ordinators of the use of official waiting time statistics in favour of responses from patient organisations), its score on the Outcomes sub-discipline is joint 10th out of the 35 countries in the comparison. It also scores relatively high (joint 8th position) on Prevention. The sub-discipline of the ranking in which Ireland particularly struggles is Accessibility, where it has the joint lowest score [21]. This would tie in with previous criticisms of the Irish system, as noted above.

Another issue worth noting is that the compilation of the data may lead to some degree of uncertainty, although this is more of an issue for private funding sources (which have changed since 2013, also making time-series comparisons more difficult). The CSO itself notes that figures for funding from non-profit institutions are under-represented because of difficulty in obtaining data and that this is an area for ongoing development [22].

Figures for out-of-pocket payments also come from a variety of sources, due to the lack of a centralised or systematic collection mechanism or agency for such information, which may raise some issues surrounding this category of funding. Data sources for this type of expenditure include “HSE financial data, tax files, Revenue Commissioners data on refunds for medical expenditure, Household Budget Survey, published accounts, price by quantity methods and residual methods.” [22: p. 5].

One potential issue with these sources is the fact that fewer than 400,000 people (in other words, less than 10 % of the population) claim refunds for medical expenditure [10], which suggests that many people who would be eligible for this tax relief do not claim it, and therefore, estimates based on the amount of tax relief claimed could under-estimate actual spending. Another would be that price by quantity methods may be restricted by the lack of reliable cost data in some sectors of the health service. Furthermore, residual methods (i.e. ascribing to out-of-pocket payments funding that is not accounted for in Government financing schemes or voluntary health care payment schemes) may lead to some degree of error.

It is also worth repeating here that the SHA figures are provisional and subject to revision. A further limitation is the break in the series in 2013, which makes historical comparisons spanning this year subject to caveat although, as noted earlier, the CSO intends to publish figures for 2011 and 2012 based on the SHA2011 methodology some time in 2017.

It has been suggested elsewhere that the reasons for the apparently relatively high expenditure on health care in Ireland revealed in the SHA figures requires further research [15]. One possible avenue for such examination is “whether the Irish system’s complex combination of the privately insured and means-tested and rationed public sector fosters cost-inflationary features like high transaction costs and SID [supplier-induced demand], which are associated with predominantly private-insurance based systems.” [23: p. 20].

Based on the analysis contained in this article, this call seems very sensible. In the meantime, care should be used in drawing conclusions about the relative value for money of the Irish health system.

Notes

Private correspondence with the Central Statistics Office has revealed that plans are in place to publish detailed data for 2011 and 2012, based on the SHA methodology, but that these will not be published until 2017. Therefore, the only years for which SHA data are available for Ireland at the time of writing are 2013 and 2014.

GDP is defined as the total value added (output) in the production of goods and services in the country. Gross National Product (GNP) is defined as the sum of GDP and Net Factor Income from the rest of the world, the latter of which is the difference between investment income and labour income earned abroad by Irish resident persons and companies (inflows) and similar incomes earned in Ireland by non-residents (outflows). GNI is equal to GNP plus EU subsidies less EU taxes [5]. Since net factor income in Ireland is heavily influenced by foreign multinationals, there is a larger difference between GDP and GNP/GNI in Ireland than in most countries.

The change in methodology in Ireland would not have significantly affected the OECD figures.

However, a counter-argument is that all of the income counted in GDP is taxable and is therefore relevant to public spending—see http://www.nerinstitute.net/blog/2016/05/14/do-we-overspend-on-health/.

In a similar manner, recently released figures showing a 26 percent increase in GDP in 2015 will mean that health spending as a percentage of GDP will fall sharply for 2015, without a fall in health spending itself.

However, there may be some data and/or methodological issues regarding private expenditure, particularly out-of-pocket payments. This is discussed further in the “Discussion and conclusions” section.

Preventive services are defined as those services “having the primary purpose of risk avoidance…” and include “information, education and counselling programmes; immunisation programmes; early disease detection programmes; healthy condition monitoring programmes; epidemiological surveillance and risk and disease control programmes; and preparing for disaster and emergency response programmes.” [4, p. 7] In an Irish context, this category primarily relates to the services provided by the HSE’s Health and Well Being Division.

Under the 2011–2016 Programme for Government, it was proposed to extend access to GP services without fees at the point of use to the entire population. It was estimated that this measure would cost €389 million [18]. If this figure were incorporated into the SHA figures (i.e., an additional €389 m into public expenditure and a corresponding fall of €389 m in private expenditure), it would shift the balance of public versus private current expenditure (in terms of percentages, based in the 2014 figures) from 69:31 to 71:29.

See http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/oireachtasbusiness/committees_list/future-of-healthcare/role/ for full details of the Committee’s role.

References

CSO (2015) System of health accounts: Ireland’s system of health accounts, annual results 2013 (preliminary). Central Statistics Office, Dublin

CSO (2016) System of health accounts: Ireland’s system of health accounts, annual results 2014. Central Statistics Office, Dublin

OECD (2015) Health at a glance 2015: OECD indicators. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris

CSO (2015) Mapping of health care services in Ireland to the functions classification (IHCA-HC) within the system of health accounts. Dublin, Central Statistics Office

CSO (2014) Measuring Ireland’s progress 2012. Central Statistics Office, Dublin

Goldrick-Kelly P (2016) Is Ireland overspending on healthcare? NERI Research inBrief, No. 34. Nevin Economic Research Institute, Dublin

OECD (2016) OECD Health Statistics online. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris. www.stats.oecd.org. Accessed 20 Sept 2016

HIA (2016) Market statistics 2015. Dublin, The Health Insurance Authority

Turner B (2013) Premium inflation in the Irish private health insurance market: drivers and consequences. Ir J Med Sc 182(4):545–550

Turner B (2015) Unwinding the State subsidisation of private health insurance in Ireland. Health Policy 119(10):1349–1357

Nolan A, Barry S, Burke S, Thomas S (2014) Observatory-WHO study on the impact of the financial crisis on health and health systems in Europe. Case Study Ireland. WHO European Observatory on Health Systems, London

Kleerekoper M (2009) Cost-effectiveness of preventive care. Endocrine Today, January 25, 2009, p. 5

Burke SA, Normand C, Barry S, Thomas S (2015) From universal health insurance to universal healthcare? The shifting health policy landscape in Ireland since the economic crisis. Health Policy 120(3):235–240

Wren M-A (2003) Unhealthy state: anatomy of a sick society. New Island, Dublin

HSE (2007) Acute hospital bed capacity review: a preferred health system in Ireland to 2020. Report prepared by PA Consulting Group. Health Service Executive, Naas

CSO (2016) StatBank service. Central Statistics Office, Dublin. www.cso.ie. Accessed 7 Jan 2016

O’Reilly D, O’Dowd T, Galway K et al (2007) Consultation charges in Ireland deter a large proportion of patients from seeing the GP: results of a cross-sectional survey. Eur J Gen Pract 13(4):231–236

Party Labour (2010) Universal health insurance—labour’s health policy. Labour Party, Dublin

HIA (2016) A review of private health insurance in Ireland by Millward Brown. The Health Insurance Authority, Dublin

Smith S (2009) Equity in health care: a view from the Irish health care system. An Adelaide health policy brief. Adelaide Hospital Society, Dublin

Health Consumer Powerhouse (2016) Euro health consumer index 2015. Health Consumer Powerhouse, Täby

CSO (2015) Mapping of the structure of health care financing in Ireland to the health care financing schemes classification (ICHA-HF) within the system of health accounts. Central Statistics Office, Dublin

Wren M-A, Connolly S (2016) Challenges in achieving universal healthcare in Ireland. Dublin, Economic and Social Research Institute

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the helpful comments of two anonymous reviewers in the preparation of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Informed consent

This article does not belong to informed consent.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Turner, B. The new system of health accounts in Ireland: what does it all mean?. Ir J Med Sci 186, 533–540 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-016-1519-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-016-1519-2